Abstract

Background

Pharmaceutical company representatives likely influence the prescribing habits and professional behaviour of physicians.

Objective

The objective of this study was to systematically review the effects of interventions targeting practising physicians’ interactions with pharmaceutical companies.

Eligibility criteria

We included observational studies, non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCTs) and RCTs evaluating legislative, educational, policy or other interventions targeting the interactions between physicians and pharmaceutical companies.

Data sources

The search strategy included an electronic search of MEDLINE and EMBASE. Two reviewers performed duplicate and independent study selection, data abstraction and assessment of risk of bias.

Appraisal and synthesis methods

We assessed the risk of bias in each included study. We summarised the findings narratively because the nature of the data did not allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. We assessed the quality of evidence by outcome using the GRADE methodology.

Results

Of 11 189 identified citations, one RCT and three observational studies met the eligibility criteria. All four studies specifically targeted one type of interaction with pharmaceutical companies, that is, interactions with drug representatives. The RCT provided moderate quality evidence of no effect of a ‘collaborative approach’ between the pharmaceutical industry and a health authority. The three observational studies provided low quality evidence suggesting a positive effect of policies aiming to reduce interaction between physicians and pharmaceutical companies (by restricting free samples, promotional material, and meetings with pharmaceutical company representatives) on prescription behaviour.

Limitations

We identified too few studies to allow strong conclusions.

Conclusions

Available evidence suggests a potential impact of policies aiming to reduce interaction between physicians and drug representatives on physicians’ prescription behaviour. We found no evidence concerning interventions affecting other types of interaction with pharmaceutical companies.

Keywords: Pharma, Gift giving, Conflict of interest, Drug industry, Primary care , Physician

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We followed Cochrane methodology for conducting this systematic review.

This is the first systematic review to focus on practising physicians.

We identified too few studies to allow strong conclusions.

Introduction

Physicians may benefit from their relationship with the pharmaceutical industry through access to information on new medicines and products. However, the direct financial rewards provided to them could also persuade them to prescribe newer and more expensive drugs for patients.1 One industry market study found that physician profiling could increase the uptake of new drugs by 30%.2 On the other hand, studies conducted in different parts of the world (eg, Canada, France, the USA, Australia and Malaysia) have consistently found that the risks and harmful effects of drugs were often not mentioned in presentations by pharmaceutical representatives to doctors.3

Similarly, there is concern that in paying for doctors’ continuing education, drug companies will influence physician behaviour for the financial benefit of the company.4 A recent review article on this subject showed that industry-supported educational activities are biased toward the financial supporter's products and that clinicians attending such events later prescribe these products more often than competing drugs.5 One study found that pharmaceutical representatives commonly use different types of ‘influence techniques’ in describing products to medical practitioners.6

As a result of these concerns, legislators have tried to improve the transparency of relationships between doctors and drug companies.3 For example, the Physician Payments Sunshine Act (Sunshine Act) in the USA requires the manufacturers of drugs, medical devices and biologicals participating in federal health care programmes to report certain payments and items of value given to physicians and teaching hospitals.7

Training programmes have also been provided to help restrict physicians’ interactions with pharmaceutical companies and include well-designed seminars, role playing, and focused curricula.8 The purpose of these programmes is to help physicians better understand the conflicts of interest associated with the acceptance of gifts and other financial incentives and their potential effect on patient care.

While at least one systematic review has assessed interventions targeting residents’ and students’ interactions with pharmaceutical companies, we are not aware of a systematic review focusing on practising physicians.8 The objective of this study was to systematically review the effects of interventions targeting practising physicians’ interactions with pharmaceutical companies.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were:

Types of studies: observational studies (eg, cohort) comparing an intervention of interest to a comparator (eg, usual practice), non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCTs) and RCTs

Types of participants: practising physicians; we did not consider medical students, physicians in training, or other health professionals

Types of interventions: legislative, educational, policy or other interventions targeting the interactions between physicians and pharmaceutical companies; examples of such interactions include contact with drug representatives, educational talks, sponsored travel, etc

Types of outcomes: knowledge of physicians (eg, about the potential effect of interactions on physician prescribing behaviour), attitude of physicians (eg, toward the usefulness of information from pharmaceutical company representatives), and behaviour of physicians (eg, prescription behaviour, the rate of contact with pharmaceutical company representatives).

We did not exclude studies based on date of publication, but did exclude studies not published in English.

Search strategy

We designed the search strategy with the help of a medical librarian (see online supplementary appendix 1). The strategy included searching MEDLINE and EMBASE electronic databases using the OVID interface in April 2014. The search combined terms for physicians and pharmaceutical, and included both free text words and medical subject heading. We did not use a search filter. Online supplementary appendix 1 provides the full details of the search strategies. Additional search strategies included a search of the grey literature (theses and dissertations). Also, we reviewed the references lists of included and relevant papers.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified citations for potential eligibility. We obtained the full text for citations judged potentially eligible by at least one of the two reviewers. The two reviewers then independently screened the full texts for eligibility. They used a standardised and pilot tested screening form and resolved disagreement by discussion.

Data collection

Two reviewers independently abstracted data from eligible studies. They used a standardised and pilot tested screening form and detailed written instructions. They resolved disagreement by discussion. The data abstracted included: the type of study; the funding source; characteristics of the population, type of exposure, and controls used; the outcomes assessed; and statistical data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers assessed in duplicate and independently the risk of bias in each eligible study. They resolved disagreements by discussion or with the help of a third reviewer. According to recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook, we used the following criteria for assessing the risk of bias in randomised studies:

Inadequate sequence generation

Inadequate allocation concealment

Lack of blinding of participants, providers, data collectors, outcome adjudicators and data analysts

Incompleteness of outcome data

Selective outcome reporting, and other bias.

We used the following criteria for assessing the risk of bias in non-randomised studies:

Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria (eg, under- or over-matching in case–control studies, selection of exposed and unexposed subjects in cohort studies from different populations)

Flawed measurement of both exposure and outcome (eg, differences in measurement of exposure such as recall bias in case–control studies, differential surveillance for outcome in exposed and unexposed subjects in cohort studies

Failure to adequately control for confounding (eg, failure to accurately measure all known prognostic factors, failure to match for prognostic factors and/or adjustment in statistical analysis

Incomplete follow-up.

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear.

Data analysis and synthesis

We assessed the agreement between reviewers for full-text screening by calculating the kappa statistic. We did not conduct a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of study design, types of interventions, outcomes assessed, and outcome measures used. Instead, we summarised the data narratively. We assessed the quality of evidence by outcome using the GRADE methodology.9

Results

Results of the search

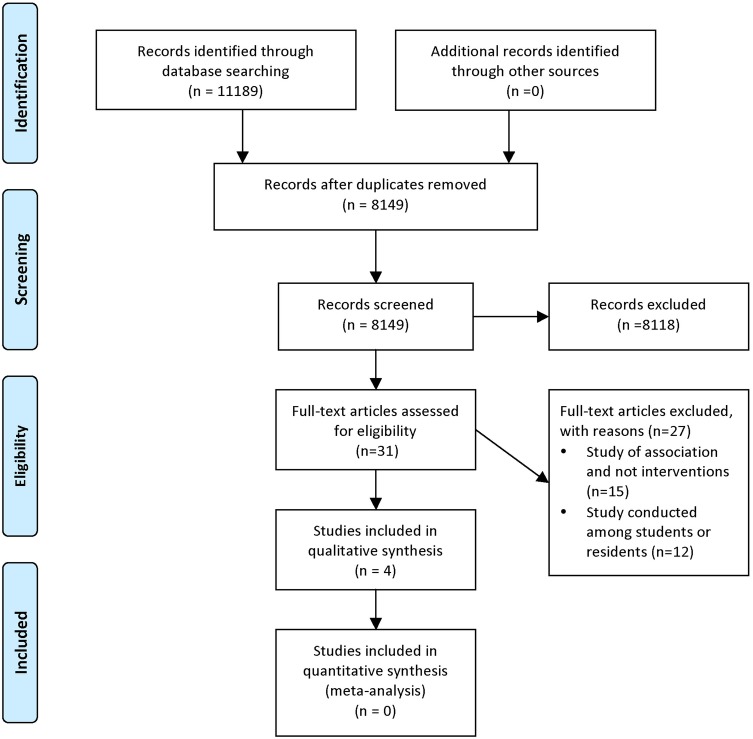

Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram. Of the 11 189 identified articles, three observational studies and one RCT met our inclusion criteria. We excluded 27 full-text articles for the following reasons: studies assessed the association between interactions with pharmaceutical companies and behaviours (and effects of interventions) (n=15); and studies were conducted among students or residents (n=12). The kappa statistic for full-text screening was 0.893, reflecting high levels of agreement.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Description of included studies

Tables 1 and 2 give the characteristics of the included studies. All these studies assessed interventions that specifically targeted the interactions of physicians with drug representatives. We did not identify any studies of interventions targeting other types of interaction with pharmaceutical companies (eg, educational talks, sponsored travel).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included randomised controlled trial

| Study name and funding | Study design | Participants, setting | Exposure | Control | Outcomes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freemantle et al,13 2000, funding by Warwickshire health authority |

Randomised controlled trial | All 79 cardiovascular practices in Warwickshire participated in the trial | 40 practices which received, in addition to what the control group received: a letter from the chief executive of the health authoritypostgraduate educational allowance accreditationa letter from the pharmaceutical advisor |

39 practices which received: practice guidelines routine marketing activities routine health authority advice |

Proportion of prescriptions in line with the guidelines (behaviour)prescribing costs | Time frame: October 1997–April 1998 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included observational studies

| Study name and funding | Study design | Participants, setting | Exposed group | Control group | Outcomes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boltri et al,10 2002, funding by the Health Resources and Services Administration |

Retrospective cohort Charts from two time periods were reviewed for a diagnosis of hypertension |

24 family practice residents and 8 clinical attending physicians at the outpatient clinic of a family practice residency programme in south-eastern USA | 507 hypertensive patients during ‘Period 2’: January and February 1998 after the policy prohibiting samples distribution was implemented in August 1997 | 422 hypertensive patients during ‘Period 1’: January and February 1997 before the policy prohibiting samples distribution was implemented | Effect of policy on prescription of first-line hypertension drugs versus prescription of second-line drugs by all physicians (by JNC VI) | Data collection of the outcome was based on the medical reports of all hypertensive patients during the two study periods |

| Spurling and Mansfield,12 2007, funding not reported |

Prospective cohort | 13 out of the 14 (7 part-time general practitioners (GPs), 3 practice nurses, 3 regular reception staff, 1 practice manager) participated Inala Health Centre general practice in Brisbane, Australia |

Policy of reduced access to pharmaceutical sales representatives including: reception staff not to make appointments for representatives or accept promotional material; representatives not allowed to access sample cupboards; GPs wishing to see representatives only allowed to do so outside consulting hours | Before policy implementation | Number of prescription per patient (behaviour)Amount of promotional material (no further details provided) Number of samples in the drug cupboard and time booked for pharmaceutical sales representatives (actual implementation of the policy) |

Timeframe: 2004 The impact of the policy was evaluated at 3 months and 9 months after its adoption Data collected through audit and staff survey |

| Hartung et al,11 2010, funding partly by an American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation Research Stimulation Grant |

Segmented linear regression models using locally obtained pharmacy claims | The Madras Medical Group, a family practice clinic employing 5 physicians and 1 physician assistant | After the implementation of a policy restricting access of pharmaceutical sales representatives to the clinic was implemented | Before the implementation of the policy, Oregon Medicaid pharmacy claims were used to control for secular prescribing changes | Percentage of branded drug use (behaviour) Percentage of promoted drug use (behaviour) Average prescription costs (cost) | Time frame: 1 April 2004 to 31 September 2007 The Medicare Part D programme was implemented in January 2006 |

JNC VI, Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.

These studies were conducted in Warwickshire (UK), central Oregon (USA), Brisbane (Australia) and south-eastern USA. Three studies evaluated the effects of the implementation of new legislation and regulatory policies,10 11 while one study evaluated the effects of various educational interventions.10 These studies assessed the impact of intervention on physician knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. The sample sizes in these studies varied from 14 to 79.

Table 3 shows the assessment of the risk of bias in the single included RCT. The risk of bias was judged to be either low or unclear for the different criteria assessed.10 Table 4 shows the assessment of the risk of bias in the three included observational studies.7–9 We judged the risk of bias associated with the exposure measurement and the completeness of data as low for all included studies. We judged the risk of bias as either low or unclear for the remaining methodological features, except for confounding, which we judged to be high risk for one study.12

Table 3.

Risk of bias in the included randomised controlled trial

| Study name | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding (participants, data collectors, outcome adjudicators) | Completeness of outcome data | Completeness of outcome reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freemantle et al,13 2000 | Low risk: ‘Practices were randomised to intervention or control using computer generated random numbers in a stratified scheme’ |

Unclear risk Not reported |

Unclear risk Not reported |

Low risk No missing data reported |

Low risk No evidence of selective outcome reporting |

Table 4.

Risk of bias in the included observational studies

| Study name | Developing and applying appropriate eligibility criteria | Measurement of exposure | Measurement of outcome | Controlling for confounding | Completeness of data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boltri et al,10 2002 | Low risk Physicians and residents in the control and exposed groups were from the same pool |

Low risk Policy applied across the clinic |

Low risk Data collection was based on medical records, and carried out by a research assistant blinded to study design and hypothesis |

Low risk ‘Logistic regression was then performed to adjust the odds ratio for the relation of physician type, prescribing patterns, and time’ |

Low risk No missing data reported |

| Spurling and Mansfield,12 2007 | Low risk Diaries chosen at random for a 1-month period. A random week was chosen for auditing doctors’ prescribing |

Low risk Policy applied across the clinic |

Unclear risk Not clear whether the survey instrument was validated |

High risk According to the authors, the possibility of confounding cannot be ruled out |

Low risk. All except one returned the completed questionnaire |

| Hartung et al,11 2010 | Unclear risk | Low risk Policy applied across the clinic |

Unclear risk Use of claim data; however, validity of the data not described |

Low risk They include ‘a contemporaneous control group of patients or clinicians also experiencing this potential confounder’ (confounding resulting from secular changes in prescribing) |

Low risk ‘Although it is possible that some prescriptions would not have been captured by using data from only one pharmacy, it seems unlikely that this subset would have introduced any systematic bias or loss of generalisability’ |

Effects of implementing new policies

As mentioned, one trial and three observational studies evaluated the effects of programme or organisational policies that limit contact between physicians and pharmaceutical company representatives.

Freemantle et al13 conducted an RCT to assess ‘a collaborative approach’ between the pharmaceutical industry and a local health authority. The collaborative approach consisted of post-graduate educational allowance accreditation and a letter from the pharmaceutical advisor asking the practice to agree to see a representative. Both the intervention and the control groups received practice guidelines, routine marketing activity, and a routine health authority advice. The authors do not provide further details about the ‘routine advice’, but health authorities in the UK apparently enact the directives of the Department of Health, implement its fiscal policy, and run or commission local health services.14 The specific objective of the intervention was to substitute in primary care a proton inhibitor for an alternative deemed therapeutically equivalent but less costly, based on ‘evidence based guidelines’. The investigators reported that prescribing in both groups ‘moved towards that recommended by the guidelines’. However, the proportion of prescriptions in line with the guidelines and the overall cost were similar between the two groups.

Boltri et al10 conducted a retrospective cohort study of a new policy prohibiting the distribution of drug samples (mainly hypertensive drugs). Participants included 24 family practice residents and eight clinical attending physicians at an outpatient clinic in south-eastern USA. At 6 months after implementation of the new policy, prescriptions of first-line medication had increased from 38% to 61% (OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.29 to 5.76).

Spurling and Mansfield12 examined a cohort of 14 participants, 3 months before and 9 months after the implementation of a new policy. This policy included: reception staff not making appointments for pharmaceutical sales representatives or accepting promotional material; pharmaceutical sales representatives not accessing sample cupboards; and general practitioners wishing to see pharmaceutical sales representatives being allowed to do so only outside consulting hours.

The investigators found that the amount of overall promotional material was reduced by 32% and 21% at 3 and 9 months, respectively, post-intervention compared to pre-intervention. The number of samples was reduced by 59% and 70% at 3 and 9 months, respectively, post-intervention compared to pre-intervention. The number of prescriptions per patient encounter fell from 0.99 pre-intervention to 0.92 and 0.54 at 3 and 9 months post-intervention, respectively. The number of generic prescriptions increased from 4% pre-intervention to 8.6% and 8.1% after 3 and 9 months post-intervention, respectively.

Hartung et al11 evaluated the effects of the implementation of new policies applied by the Madras Medical Group family practice clinics (Ohio, USA). The policies included discontinuing seeing pharmaceutical representatives and stopping the acceptance and distribution of drug samples. The control group consisted of a regionally discrete sample of the Oregon Medicaid programme. Medicaid and Medicare are two government programmes that provide medical and health-related services to specific groups of people in the USA. The analysis used segmented linear regression models to compare 92 223 and 178 028 pharmacy claims from the intervention and control groups covering 18 months before and 18 months after policy implementation. Overall, use of ‘promoted agents’ decreased by 1.4%, while the use of ‘non-promoted branded agents’ increased by 3.0%. However, the results varied by the class of drug. Interestingly, the investigators found that the average prescription drug cost increased significantly (by US$5.2) immediately after policy implementation.

Assessment of the quality of evidence

Following the GRADE methodology, we judged the quality of evidence from the RCT as moderate due to imprecision (only 79 participants). We judged the quality of evidence from the observational studies as low due to study design. Overall risk of bias was judged as low, and we did not find any evidence of inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness or publication bias warranting further downgrading.

Discussion

In summary, our systematic review identified one RCT13 and three observational studies.10 11 All included studies targeted one type of interaction with pharmaceutical companies, that is, interactions with drug representatives. The RCT found no effect of a ‘collaborative approach’ between the pharmaceutical industry and the health authority. The three observational studies found a positive effect on prescription behaviour of clinic policies aiming to reduce interaction between physicians and pharmaceutical companies (in the form of free samples, promotional material, and meetings with pharmaceutical company representatives). Our systematic review did not identify any eligible studies assessing other relevant types of interactions between physicians and pharmaceutical companies, such as educational talks or sponsored travel.

A major strength of this study is the use of Cochrane methodology for conducting the systematic review. In addition, this is the first systematic review to focus on practising physicians. Some of the limitations of this review are related to those of the included studies. Indeed, we identified too few studies to allow strong conclusions. Also, the included studies were subject to risk of bias related to the lack of validity of outcome measurement, and inadequate handling of significant potential confounders.

The available evidence does not provide clear answers on why a ‘collaborative approach’ between the pharmaceutical industry and a health authority did not work, while policies restricting certain types of interaction between physicians and pharmaceutical companies worked. It might be that restriction approaches are easier to implement compared to more complex interventions such collaborative approaches. Also, it might be that the link between restrictive interventions and the desired outcome is clearer and shorter compared with collaborative interventions.

The Sunshine Act enacted in 2010 in the USA marks the first Congressional involvement in regulating the disclosure by physicians of payments by pharmaceutical companies. Under this act, manufacturers of drugs, medical devices and biologicals participating in US federal health care programmes are required to report certain payments and items of value given to physicians and teaching hospitals (eg, speaking fees, consulting arrangements, and free food). The purpose is to prevent undue influence and protect the public interest.4 The Sunshine Act could be viewed as a systems intervention targeting physicians’ interactions with pharmaceutical companies. Although we have not identified at this point any study assessing the impact of this act on the prescription behaviour of physicians, we expect such studies to become available over the next few years.

While acknowledging the importance of regulation, some have called for physicians to take the lead and minimise any undue commercial influence on their profession.5 Professional organisation have a particularly important responsibility, given the relationships between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry may erode social trust in medical professionals.5

A 2005 joint report by the WHO and Health Action International (HAI) reported on interventions to counter promotional activities.15 The evidence presented in that report was not eligible for our systematic review, mostly because it related to interventions on students or residents. Nevertheless, the findings suggested that interventions such as industry self-regulation and guidelines for sales representatives are not effective, while education about drug promotion might influence physician attitudes. At that time, the report called for research on interventions that could affect doctors’ behaviour.

We identified only one other systematic review of the literature addressing the same question but with residents and students instead of practising physicians.8 The review identified 12 eligible studies, seven before–after studies and three controlled trials. The findings suggested that well-designed seminars, role-playing and focused curricula could affect trainee attitudes and behaviour. However, it was not clear whether these effects were long-term.

Implications for practice

Based on the evidence, health administrators aiming to reduce the negative impact of physicians’ interaction with pharmaceutical companies may decide not to spend their resources on ‘collaborative approaches’ between the pharmaceutical industry and the health authority. Implementing policies restricting free samples, industry-supplied promotional materials, and meetings with pharmaceutical company representatives might be more beneficial.

However, a potential limitation of implementing restriction policies is the creation of an ‘information gap’ that has been filled so far by the pharmaceutical representatives (eg, information on new drugs). Indeed, representatives provide information on indications and dosages of medications to relatively high percentages of physicians.3 Sales representatives are frequently the only source of information about medicines in developing countries, where there may be as many as one representative for every five doctors.16

As an alternative to complete restriction of interactions, some jurisdictions have attempted to regulate them. In Australia, the Australian Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association has a code of conduct covering sales representatives. Although the code does not state what kind of information sales representatives must provide, it does insist that their presentations be current, accurate and balanced.16

Implications for research

Future studies should address the methodological limitations of the available evidence. Well-designed randomised trials should be conducted. Future observational studies should aim to correctly assess the exposure, controlling for all confounders and minimising missing data. There is also a need for studies of other kinds of interventions (eg, educational and legislative interventions), as well as other types of interactions with pharmaceutical companies (eg, educational talks, sponsored travel). As the Sunshine Act is implemented, we expect over the next few years the publication of studies assessing its impact on the prescription behaviour of physicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Aida Farha for her valuable help in designing the search strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: EAA, LA, KB: concept and design; LA, LK, HN, HB, RF: study selection; LA, LK: data collection; EAA, LA, LK, HB, KB: data analysis and interpretation; EAA, LA: drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Tong KL, Lien CY. Do pharmaceutical representatives misuse their drug samples? Can Fam Physician 1995;41:1363–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DataMonitor. Personalized physician marketing: Using physician profiling to maximize returns. New York, NY, 2001. http://www.datamonitor.com http://www.informabusinessinformation.com/About-Us/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Othman N, Vitry AI, Roughead EE, et al. Medicines information provided by pharmaceutical representatives: a comparative study in Australia and Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2010;10:743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon D, Takhar J, Macnab J, et al. Controlling quality in CME/CPD by measuring and illuminating bias. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2011;31:109–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grande D. Limiting the influence of pharmaceutical industry gifts on physicians: self-regulation or government intervention? J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:79–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roughead EE, Harvey KJ, Gilbert AL. Commercial detailing techniques used by pharmaceutical representatives to influence prescribing. Aust N Z J Med 1998;28:306–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman E. Everything you need to know about the Sunshine Act. BMJ 2013;347:f4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll AE, Vreeman RC, Buddenbaum J, et al. To what extent do educational interventions impact medical trainees’ attitudes and behaviors regarding industry-trainee and industry-physician relationships? Pediatrics 2007;120:e1528–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boltri JM, Gordon ER, Vogel RL. Effect of antihypertensive samples on physician prescribing patterns. Fam Med 2002;34:729–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartung DM, Evans D, Haxby DG, et al. Effect of drug sample removal on prescribing in a family practice clinic. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:402–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spurling G, Mansfield P. General practitioners and pharmaceutical sales representatives: quality improvement research. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:266–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freemantle N, Johnson R, Dennis J, et al. Sleeping with the enemy? A randomized controlled trial of a collaborative health authority/industry intervention to influence prescribing practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000;49:174–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wikepedia. NHS strategic health authority. Secondary NHS strategic health authority. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NHS_strategic_health_authority

- 15.Norris P, Herxheimer A, Lexchin J, et al. Drug promotion—what we know, what we have yet to learn—reviews of materials in the WHO/HAI database on drug promotion. 2005.. EDM Research Series No. 032

- 16.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA 2000;283:373–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.