Abstract

Flavonoids are secondary metabolites that play important roles throughout the plant life cycle and have potential human health beneficial properties. Flavonols, anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins (PAs or condensed tannins) are the three main class of flavonoids found in Arabidopsis thaliana. We have previously shown that PA biosynthesis (occurring exclusively in seeds) involves the transcriptional activity of four different ternary protein complexes composed of different R2R3-MYB and bHLH factors together with TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA 1 (TTG1), a WD repeat containing protein. We have also identified their direct targets, the late biosynthetic genes. In this study, we have further investigated the transcriptional capacity of the MBW complexes through transactivation assays in moss protoplast and overexpression in Arabidopsis siliques. Results provide new information for biotechnological engineering of PA biosynthesis, as well as new insights into the elucidation of the mechanisms that govern the interactions between MBW complexes and the DNA motifs they can target.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, Physcomitrella patens, TT2, TT8, TTG1, cis-element, overexpression, transcription factor, transient assay, transparent testa

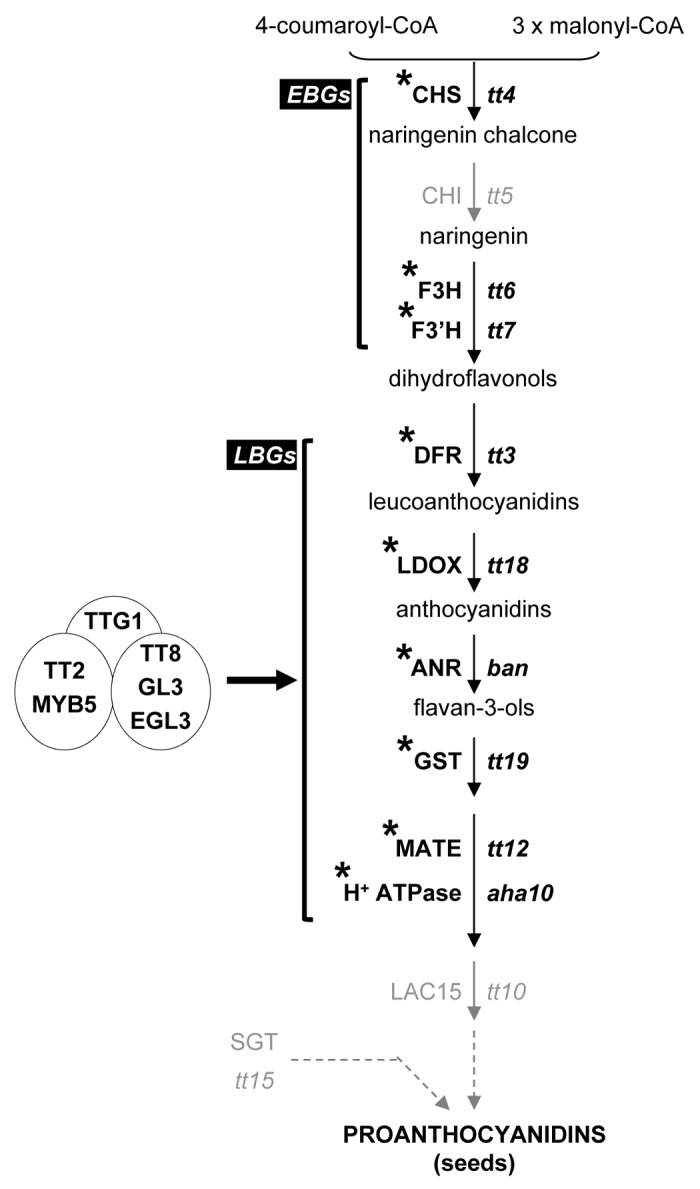

Flavonoids are one of the largest classes of plant secondary metabolites, which include flavonols, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins (PAs or condensed tannins). Flavonoids play important roles throughout the plant life cycle and have potential human health beneficial properties.1,2 In Arabidopsis thaliana, PAs are specifically synthesized and accumulated in the inner integument of the seed coat in which they are thought to play an important role in protecting the embryo against biotic and abiotic stresses,3 conferring brown color to mature seeds once oxidized.4 Arabidopsis mutants impaired in flavonoid accumulation have been identified through visual screenings for altered seed pigmentation, which results in the transparent testa (tt) phenotype.1,5 Most of these mutants have been characterized at the molecular level allowing to decipher the core of this complex biosynthetic pathway.6 In Arabidopsis, it is composed of at least two distinctly co-regulated groups of genes, namely the early and late biosynthetic genes (EBGs and LBGs).1 The EBGs are involved in biosynthesis of the common precursor of the three classes of flavonoids (i.e. dihydroflavonols), whereas the LBGs are specific to anthocyanin and PA biosynthesis (Fig. 1). Therefore, LBGs include DFR (dihydroflavonol-4-reductase), LDOX/ANS (leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase/ anthocyanidin synthase), BAN/ANR (BANYULS /anthocyanidin reductase), TT12 (MATE transporter), TT19/GST26/GSTF12 (glutathione-S-transferase), and AHA10 (H+-ATPase isoform 10). However, TT10/LAC15 (laccase 15) and TT15/UGT80B1 (UDP-glucose:sterol-glucosyltransferase), which are both critical for PA biosynthesis,4,7 could not be classified as either EBG or LBG.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the Arabidopsis thaliana proanthocyanidin biosynthetic pathway. Four different ternary protein complexes composed of R2R3-MYB and R/B-like bHLH transcription factors together with the WD repeat-containing protein TTG1 directly regulate the expression of the LBGs (late biosynthetic genes) in a tissue-specific manner. These (MBW) complexes are TT2-TT8-TTG1, MYB5-TT8-TTG1, TT2-EGL3-TTG1, and TT2-GL3-TTG1. (*) genes whose expression is directly induced in Arabidopsis siliques by TTG1:GR induction and in gray those the expression of which is not affected. The names of the structural proteins are indicated in capital letters and the corresponding mutants in lower-case italics. CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3H, flavonol 3-hydroxylase; F3′H, flavonol 3′-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase; DFR, dihydroflavonol-4-reductase; LDOX, leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (also called ANS: anthocyanidin synthase); ANR, anthocyanidin reductase; MATE, multidrug and toxic efflux transporter; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; SGT, UDP-glucose:sterol-glucosyltransferase; LAC15, laccase 15. Arrows indicate the different steps leading to the formation and accumulation of flavonoids in Arabidopsis; dashed lines indicate multiple steps; circles correspond to transcription factors; EBGs, early biosynthetic genes.

We have recently demonstrated that PA biosynthesis relies on the transcriptional activity of R2R3-MYB (TT2/MYB123 and MYB5) and R/B-like basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH: GL3/bHLH001, EGL3/bHLH002, and TT8/bHLH042) proteins which form four different ternary complexes (MBW) with TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 (TTG1), a WD repeat-containing protein.8 These four MBW complexes (namely TT2-TT8-TTG1, MYB5-TT8-TTG1, TT2-EGL3-TTG1, and TT2-GL3-TTG1) directly regulate the expression of the LBGs, in a tissue-specific manner.8 The TT2-TT8-TTG1 complex is the main complex in regulating PA biosynthesis.8 Similar MBW protein complexes are involved in the transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis, in which PRODUCTION OF ANTHOCYANIN PIGMENT 1 (PAP1/MYB75) and 2 (PAP2/MYB90) ensure most of the R2R3-MYB function.9 MBW complexes regulating PA and anthocyanin biosynthesis have been characterized in various plant species such as maize (Zea mays), petunia (Petunia hybrida), grapes (Vitis vinifera), apples (Malus domestica), and strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) fruits.2,10,11

PAP1 overexpression in Arabidopsis as observed in the PAP1-D activation tagging mutant led to both over- and ectopic accumulation of anthocyanin in various plant organs, including leaves, stems, flowers and silique valves.12 Similar observations were made when the ArabidopsisPAP1 gene was overexpressed in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv xanthi).12 At the molecular level, PAP1 overexpression was sufficient to transcriptionally induce the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway leading to anthocyanin accumulation, from biosynthesis to storage, which includes the EBGs and most of the LBGs (Fig. 1).12-14 In contrast, the ectopic expression of TT2 can trigger PA accumulation in Arabidopsis seed coat, but not in vegetative parts of the plant.15 Nevertheless, the expression of BAN is sufficient, in addition to PAP1, for accumulating PA in tobacco and Medicago truncatula leaves.16 Similarly, PAs accumulation has been observed in some vegetative tissues when TT2 was overexpressed in PAP1-D plants.17 Interestingly, the overexpression of the ArabidopsisTT2 gene was sufficient to trigger PA accumulation in hairy roots of M. truncatula.18 Taken together, these results demonstrated that PAP1 and TT2 have different targets in planta. In this regard, a recent study has shown that DNA binding differences between TT2 and the PAP proteins in planta can be explained by a few amino acids present in the R2 and R3 domains of these TFs.19 Altogether these results also showed that TT2 (and PAP1) can activate different targets depending on the “cellular” context (e.g., Arabidopsis seed coat, vegetative tissues, cell cultures or M. truncatula hairy roots).

In order to better understand the underlying molecular mechanisms, some transactivation assays were performed in moss (Physcomitrella patens) protoplasts.20 For this purpose the promoters of 12 PA biosynthetic genes (Fig. 1) were fused to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene, and then co-transfected in moss protoplasts alone or in combination with one, two or three of the studied transcriptional regulators (i.e., TT2, TT8, and TTG1). These promoter fragments have been already shown to be active in PA and anthocyanin accumulating cells.8 Transactivation activities were monitored by GFP fluorescence.20

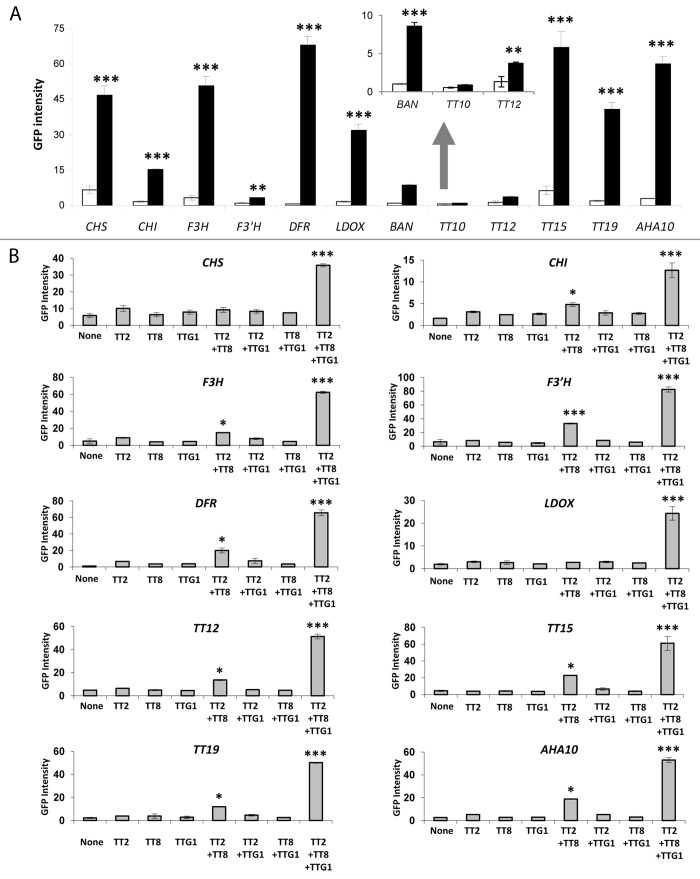

An induction of GFP fluorescence (i.e. above the fluorescence of the promoter alone) was observed for all the tested promoters but TT10/LAC15, when TT2, TT8, and TTG1 were expressed simultaneously (Fig. 2A). A strong fluorescence signal was detected for the CHS (chalcone synthase), CHI (chalcone isomerase), F3H (flavonol 3-hydroxylase), DFR, LDOX, BAN, TT15/UGT80B1, TT19, and AHA10 promoters, whereas a slight but significant induction was observed for the promoters of F3′H (flavonol 3′-hydroxylase) and TT12. Interestingly, this experiment revealed that the TT2-TT8-TTG1 complex can activate the expression of both the EBGs and TT15, in addition to the LBGs, at least in moss protoplasts. These data are consistent with previous experiments performed in grapes cells in which the authors have shown that the overexpression of the grapes VvMYBPA1 (grapes homolog of TT2) alone or in combination with EGL3, TT8 or VvMYC1 (grapes homolog of TT8) induces VvCHI (EBG) or VvANR (LBG) promoter activities.21

Figure 2. Transactivation assays in moss (Physcomitrella patens) protoplasts. (A) The TT2-TT8-TTG1 protein complex activates the transcription from the promoters of the EBGs (CHS, CHI, F3H, and F3′H), LBGs (DFR, LDOX, BAN, TT12, TT19, and AHA10) and TT15. Transactivation activities were measured by GFP intensity of arbitrary units of protoplasts co-transfected with the studied promoters alone (white bars) or in combination with the TT2-TT8-TTG1 protein complex (black bars). (B) TT2 and TT8 are sufficient to activate the transcription from all the studied promoters but CHS and LDOX. In this analysis, F3′H and TT12 promoter regions were fused to the 35S cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) minimal promoter sequence as described previously.8 Student t test significant difference: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Error bars, ± SE from three biological repetitions. none, protoplasts transformed with the assayed promoters alone.

A slight increase in GFP intensity was also observed with the CHI, F3H, F3′H, DFR, TT12, TT15, TT19, and AHA10 promoters, when TT2 was assayed with TT8 but without TTG1 (Fig. 2B). This later finding was consistent with yeast two hybrid analyses in which TT2 and TT8 were able to activate the transcription from the BAN promoter when expressed simultaneously.22 Nevertheless, in planta and in Arabidopsis protoplasts, the presence of TTG1 is required for the activation of the BAN promoter.22,23 Finally, the lack of induction for the promoter of TT10 was fully consistent with previous finding showing that TT10 is not a target of the MBW complexes in planta.8

The ability of the MBW complexes to induce the expression of the EBGs and TT15 was then investigated in planta by using transgenic plants that constitutively express the inducible TTG1:GR chimeric protein (a translational fusion between TTG1 and the glucocorticoid receptor8,22). In these plants, the translocation of the TTG1:GR chimeric protein into the nucleus occurs only in the presence of dexamethasone (DEX).

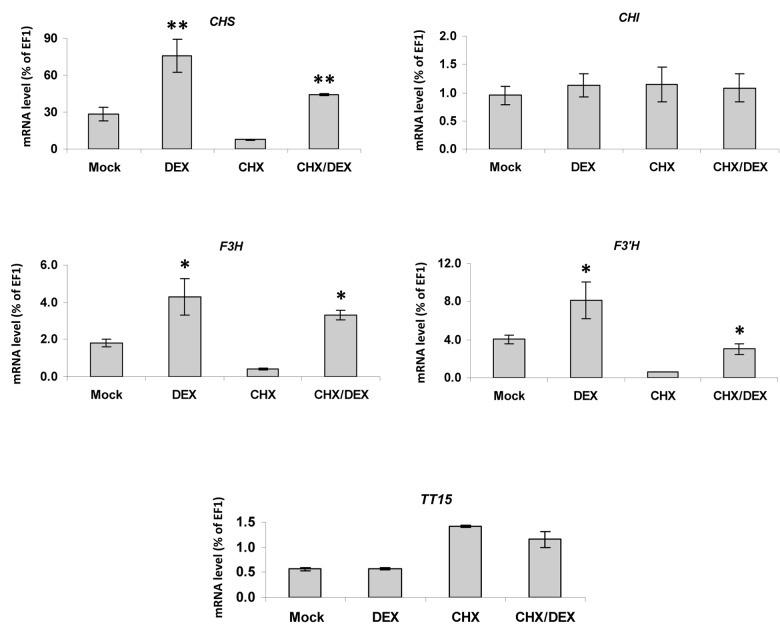

Quantitative RT-PCR experiments revealed that CHS, F3H and F3′H mRNA steady-state levels were directly increased in response to TTG1 induction (Fig. 3), as this increase was observed when 4-d-old siliques were treated with DEX alone or in combination with cycloheximide (DEX/CHX), an inhibitor of protein translation. In contrast to what has been observed in transient assays performed in moss protoplasts CHI and TT15 mRNA levels were unaffected after TTG1:GR inductions. We deduced that CHI gene activation in Arabidopsis might require other factors in addition to TTG1. This experiment suggested that the induction of CHI expression might be one of the limiting steps for the enhancement of PA accumulation, at least in Arabidopsis seed. This limiting step could be species specific, as the ectopic expression of the grape TT2 homologs VvMYBPA1 (seed specific) and VvMYBPA2 (expressed in exocarp of young berries) in grapevine hairy roots induces both PA accumulation and EBGs (VvCHS, VvCHI, VvF3H, and VvF3′H) expression.24

Figure 3.CHS, F3H, F3′H, and TT15 expression in Arabidopsis siliques is directly induced by the activation of TTG1:GR. Experiments were performed using plants that constitutively express the inducible TTG1:GR chimeric protein (a translational fusion between TTG1 and the glucocorticoid receptor). The steady-state level of CHS, CHI, F3H, F3′H and TT15 mRNA was measured by quantitative RT-PCR on 4-d-old siliques. Values are expressed as a percentage of the constitutively expressed EF1αA4 gene. Student t test significant difference: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Error bars, ± SE from three biological repetitions. Mock, buffer; DEX, dexamethasone; CHX, cycloheximide.

The molecular mechanisms that control TT15 expression are still not understood. Our results suggested that TT15 expression that is sensitive to CHX treatment could be under the control of a transcriptional repressor.

Transcriptional modulation of gene expression relies on specific interactions between DNA motifs (cis-regulatory elements generally located in their promoter) and transcriptional regulators (trans factors). In this regard, how TTG1-dependent complexes regulate the spatio-temporal pattern of expression of the PA and anthocyanin biosynthetic genes is still an open question. Nevertheless, because TTG1 is not absolutely required in all biological systems used for inducing BAN expression, it suggested that TTG1 role might be to stabilize the interaction between TT2 and TT8 or to counteract the activity of a negative regulator of this interaction.

Some cis-elements gathered from the characterization of BAN and TT8 promoters led to the identification of three types of regulatory sequences that play a critical role in the regulation of their expression.20,25 Two of these DNA motifs belong to the MYB-core (CNGTTR) and E-box (CANNTG) class of cis-regulatory sequences that are targeted by the R2R3-MYB (i.e. TT2 and MYB5) and bHLH (i.e. GL3, EGL3 and TT8) transcription factors, respectively. The third class corresponds to the AC-rich cis-regulatory sequences (also called AC-elements) and was shown to be necessary for TT8 expression in both seeds and vegetative tissues.25 This later group is well known to be the target of R2R3-MYBs26-28; however, to date it is still unclear which transcription factors are actually regulating PA biosynthesis through these AC-elements.25

MYB-core, AC-element and E-box motifs are all present in the minimal promoter (upstream from the translational start site) of all the LBGs but LDOX, which has no E-box (Table 1).8 The absence of an E-box in the LDOX promoter suggests that EGL3 and TT8 may recognize a cis-regulatory sequence that has not yet been characterized or bind indirectly to the promoter through the interaction with another transcription factor. These three regulatory sequences are also found in the promoter of the other studied genes albeit with some restrictions. CHI and F3′H promoters do not display any MYB-core or AC-rich cis-regulatory motifs (both motifs being targeted by R2R3-MYBs), respectively, whereas none of these two elements is present on the promoter of TT10 (Table 1). Altogether, sequence analyses indicate that all the EBGs as well as TT15 possess at least one R2R3-MYB and one bHLH binding site in their promoter. This finding could explain why trans-activations were observed in moss protoplasts in the presence of TT2, TT8, and TTG1 (Fig. 2). Similar results have been obtained in Arabidopsis protoplasts showing that two maize transcription factors orthologous of TT2 and TT8 (namely C1 and Sn, respectively) are able to trans-activate CHS promoter through two cis-regulatory sequences that correspond to an AC-rich motif (named MYB-recognition element or MRE) and an E-box (named R response element or RRE).29 Similarly, trans-activation of BAN promoter by C1 and Sn has been observed in Arabidopsis protoplasts.22 However, the analysis of siliques overexpressing the TTG1:GR chimeric protein highlights that transcriptional regulation of PA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis cannot be resumed to the sole interaction between the MBW complexes and some cis-regulatory elements, as CHI and TT15 expression was unaffected upon DEX or DEX/CHX induction (Fig. 3).

Table 1. Summary of the R2R3-MYB and R/B-like bHLH cis-regulatory elements identified in the promoters of the genes involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana that were analyzed in this study.

| Promoters | Conserved regulatory sequence | |||||

| Gene | size (bp) | MYB-core | AC-element | E-box | ||

| CNGTTR | (A/C)CC(T/A)A(A/C)(C/G) | CANNTG | ||||

| EBGs | CHS | 1211 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| CHI | 1187 | 0 | 2 | 3 | ||

| F3H | 901 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| F3′H | 1472 | 1 | 0 | 6 | ||

| LBGs | DFR | 302 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| LDOX | 336 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| BAN | 236 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| TT12 | 464 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| TT19 | 259 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| AHA10 | 328 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| TT10 | 1473 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| TT15 | 2819 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

The ectopic expression of TTG1-dependent complexes confirms their ability to activate the expression of a subset of genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis that they do not usually target.8 Interestingly, depending on the biological system used, moss protoplasts or siliques, expression of the EBGs and TT15 or the EBGs without CHI are induced, respectively. This later result indicates that the limiting step in enhancing PA biosynthesis in seed resides at least partly in the lack of induction of CHI expression in response to the overexpression of TTG1. However, CHI expression is certainly not the sole step that limits the ectopic accumulation of PAs throughout the plant body, and additional factors remain to be characterized. It could be for instance hypothesized that in vegetative tissues specific co-activators or repressors are absent or present, respectively.30 In order to identify new molecular actors involved in controlling PA accumulation pattern one could envisage a genetic screen aiming at identifying TT2 overexpressing plants that ectopically accumulate PAs. The data presented herein also suggests that TTG1 overexpression is sufficient to increase the stability of the interaction occurring between the R2R3-MYB and the bHLH transcription factors that in turn enhances the expression of the targeted genes. Altogether this study provides some new information for biotechnological engineering of PAs biosynthesis. Moreover, it highlights the limits of the different methods based on the overexpression of transcriptional regulators (i.e. transactivation assays and transgenic plants) in identifying their direct physiological targets.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

W.X.’s work was generously supported by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) of China.

References

- 1.Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I, Routaboul JM, Baudry A, Pourcel L, Nesi N, Caboche M. Genetics and biochemistry of seed flavonoids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:405–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petroni K, Tonelli C. Recent advances on the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in reproductive organs. Plant Sci. 2011;181:219–29. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debeaujon I, Léon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M. Influence of the testa on seed dormancy, germination, and longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:403–14. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pourcel L, Routaboul JM, Kerhoas L, Caboche M, Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I. TRANSPARENT TESTA10 encodes a laccase-like enzyme involved in oxidative polymerization of flavonoids in Arabidopsis seed coat. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2966–80. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koornneef M. Mutations affecting the testa colour in Arabidopsis. Arabidopsis Information Service. 1990;27:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Routaboul JM, Dubos C, Beck G, Marquis C, Bidzinski P, Loudet O, Lepiniec L. Metabolite profiling and quantitative genetics of natural variation for flavonoids in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:3749–64. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeBolt S, Scheible WR, Schrick K, Auer M, Beisson F, Bischoff V, Bouvier-Navé P, Carroll A, Hematy K, Li Y, et al. Mutations in UDP-Glucose:sterol glucosyltransferase in Arabidopsis cause transparent testa phenotype and suberization defect in seeds. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:78–87. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu W, Grain D, Bobet S, Le Gourrierec J, Thévenin J, Kelemen Z, Lepiniec L, Dubos C. Complexity and robustness of the flavonoid transcriptional regulatory network revealed by comprehensive analyses of MYB-bHLH-WDR complexes and their targets in Arabidopsis seed. New Phytol. 2014;202:132–44. doi: 10.1111/nph.12620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appelhagen I, Jahns O, Bartelniewoehner L, Sagasser M, Weisshaar B, Stracke R. Leucoanthocyanidin Dioxygenase in Arabidopsis thaliana: characterization of mutant alleles and regulation by MYB-BHLH-TTG1 transcription factor complexes. Gene. 2011;484:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hichri I, Barrieu F, Bogs J, Kappel C, Delrot S, Lauvergeat V. Recent advances in the transcriptional regulation of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:2465–83. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaart JG, Dubos C, Romero De La Fuente I, van Houwelingen AM, de Vos RC, Jonker HH, Xu W, Routaboul JM, Lepiniec L, Bovy AG. Identification and characterization of MYB-bHLH-WD40 regulatory complexes controlling proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) fruits. New Phytol. 2013;197:454–67. doi: 10.1111/nph.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borevitz JO, Xia Y, Blount J, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2383–94. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi MZ, Xie DY. Features of anthocyanin biosynthesis in pap1-D and wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana plants grown in different light intensity and culture media conditions. Planta. 2010;231:1385–400. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi MZ, Xie DY. Engineering of red cells of Arabidopsis thaliana and comparative genome-wide gene expression analysis of red cells versus wild-type cells. Planta. 2011;233:787–805. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nesi N, Jond C, Debeaujon I, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. The Arabidopsis TT2 gene encodes an R2R3 MYB domain protein that acts as a key determinant for proanthocyanidin accumulation in developing seed. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2099–114. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie DY, Sharma SB, Wright E, Wang ZY, Dixon RA. Metabolic engineering of proanthocyanidins through co-expression of anthocyanidin reductase and the PAP1 MYB transcription factor. Plant J. 2006;45:895–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma SB, Dixon RA. Metabolic engineering of proanthocyanidins by ectopic expression of transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005;44:62–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pang Y, Peel GJ, Sharma SB, Tang Y, Dixon RA. A transcript profiling approach reveals an epicatechin-specific glucosyltransferase expressed in the seed coat of Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14210–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805954105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heppel SC, Jaffé FW, Takos AM, Schellmann S, Rausch T, Walker AR, Bogs J. Identification of key amino acids for the evolution of promoter target specificity of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin regulating MYB factors. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82:457–71. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thévenin J, Dubos C, Xu W, Le Gourrierec J, Kelemen Z, Charlot F, Nogué F, Lepiniec L, Dubreucq B. A new system for fast and quantitative analysis of heterologous gene expression in plants. New Phytol. 2012;193:504–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hichri I, Heppel SC, Pillet J, Léon C, Czemmel S, Delrot S, Lauvergeat V, Bogs J. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MYC1 is involved in the regulation of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in grapevine. Mol Plant. 2010;3:509–23. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baudry A, Heim MA, Dubreucq B, Caboche M, Weisshaar B, Lepiniec L. TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2004;39:366–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Debeaujon I, Nesi N, Perez P, Devic M, Grandjean O, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. Proanthocyanidin-accumulating cells in Arabidopsis testa: regulation of differentiation and role in seed development. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2514–31. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terrier N, Torregrosa L, Ageorges A, Vialet S, Verriès C, Cheynier V, Romieu C. Ectopic expression of VvMybPA2 promotes proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in grapevine and suggests additional targets in the pathway. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1028–41. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu W, Grain D, Le Gourrierec J, Harscoët E, Berger A, Jauvion V, Scagnelli A, Berger N, Bidzinski P, Kelemen Z, et al. Regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis involves an unexpected complex transcriptional regulation of TT8 expression, in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2013;198:59–70. doi: 10.1111/nph.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prouse MB, Campbell MM. The interaction between MYB proteins and their target DNA binding sites. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1819:67-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Prouse MB, Campbell MM. Interactions between the R2R3-MYB transcription factor, AtMYB61, and target DNA binding sites. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romano JM, Dubos C, Prouse MB, Wilkins O, Hong H, Poole M, Kang KY, Li E, Douglas CJ, Western TL, et al. AtMYB61, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor, functions as a pleiotropic regulator via a small gene network. New Phytol. 2012;195:774–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmann U, Sagasser M, Mehrtens F, Stracke R, Weisshaar B. Differential combinatorial interactions of cis-acting elements recognized by R2R3-MYB, BZIP, and BHLH factors control light-responsive and tissue-specific activation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis genes. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57:155–71. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-6910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li S. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis: Fine-tuning of the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;8 doi: 10.4161/psb.27522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]