Abstract

Objectives

Smoking, diabetes, male sex, hypercholesterolaemia and hypertension are well-established risk factors for the development of coronary artery disease (CAD). However, less is known about their role in influencing the outcome in the event of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The aim of this study was to determine if these risk factors are associated specifically with acute myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina (UA) in patients with suspected ACS.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Patients admitted to the coronary care unit, via the emergency room, at a central county hospital over a 4-year period (1992–1996).

Participants

From 5292 patients admitted to the coronary care unit, 908 patients aged 30–74 years were selected, who at discharge had received the diagnosis of either MI (527) or UA (381). A control group consisted of 948 patients aged 30–74 years in whom a diagnosis of ACS was excluded.

Main outcome measures

MI or UA.

Results

Current smoking (OR 2.42 (1.61 to 3.62)), impaired glucose homoeostasis defined as glycated haemoglobin ≥5.5% + blood glucose ≥7.5 mM (OR 1.78 (1.19 to 2.67)) and male sex (OR 1.71 (1.21 to 2.40)) were significant factors predisposing to MI over UA, in the event of an ACS. Compared with the non-ACS group, impaired glucose homoeostasis, male sex, cholesterol level and age were significantly associated with development of an ACS (MI and UA). Interestingly, smoking was significantly associated with MI (OR 2.00 (1.32 to 3.02)), but not UA.

Conclusions

Smoking or impaired glucose homoeostasis is an acquired risk factor for a severe ACS outcome in patients with CAD. Importantly, smoking was not associated with UA, suggesting that it is not a risk factor for all clinical manifestations of CAD, but its influence is important mainly in the acute stages of ACS. Thus, on a diagnosis of CAD, the cessation of smoking and management of glucose homoeostasis are of upmost importance to avoid severe subsequent ACS consequences.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The patients were recruited before the introduction of percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft and modern antithrombotic drugs in the standard management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Thus, it was possible to identify progression to unstable angina (UA) or myocardial infarction (MI) as distinct outcome groups within the cohort, in the absence of interventions that would otherwise influence the thrombotic processes involved in ACS.

The control group of patients without ACS had a similar initial management routine following presentation to the emergency room, that is, transfer to the coronary care unit for observation until an ACS diagnosis was excluded, and on discharge diagnosed as not even suffering from stable coronary artery disease.

The study was based in a single centre with the same two cardiologists evaluating and categorising all 5292 patients, using consistent criteria.

Some of the UA cases would most likely have been diagnosed as non-ST-elevation MI using the most recent criteria of MI.

The control group is not representative of the general population.

Treatments and risk factor profiles have partly evolved since the study was performed.

Introduction

Smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension and dyslipidaemia have, together with age and sex, been established as risk factors for the development of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD). Thus, these are targets for treatment to slow the progression of disease and to reduce the risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) consequences, such as myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina (UA).1 However, the influence of these risk factors on the nature of any CAD-associated ACS is less well understood.

The initiating event of ACS is thought to involve the exposure of a prothrombotic surface, either through atherosclerotic plaque rupture or disruption of the overlying endothelial surface. The resulting thrombosis formation can permanently occlude the lumen of a coronary artery and cause myocardial cell death and the induction of MI. However, in other cases, it can be transient or only partially occlude the vessel, inducing only UA.1 It is not known why some patients with CAD are predisposed to the former rather than the latter outcome. The thrombogenicity of blood at the time of the acute event is likely to play a role, consistent with the clinical observation that rapid initiation of antithrombotic treatment (eg, acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, fondaparinux) in ACS significantly improved the outcome.2 However, the role of the established risk factors for the underlying CAD in the ACS outcome has not been well studied. The rationale of the current study was to further clarify this in the Carlscrona Heart Attack Prognosis Study (CHAPS).

CHAPS constitutes a patient cohort recruited before the introduction of a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery and modern antithrombotic drugs. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this study is unique in that UA and MI could be identified as distinct groups within an ACS population, with their respective risk factors (diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, smoking, age and sex) analysed separately.

Materials and methods

Patient recruitment

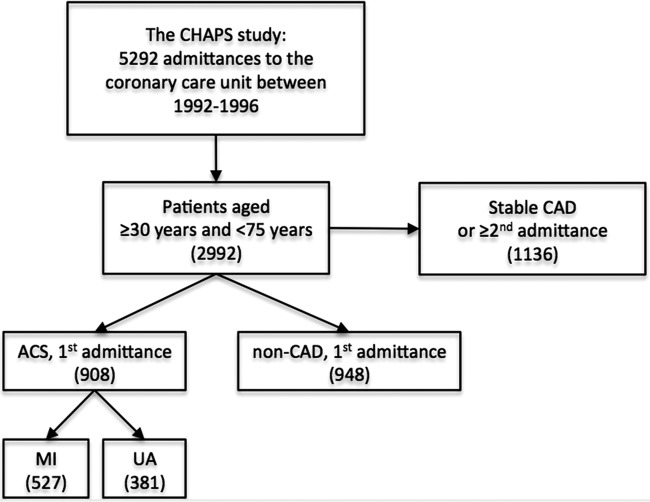

CHAPS recruited 5292 consecutive patients admitted to the coronary intensive care unit with acute chest pain (indicative of a possible ACS) at Blekinge Hospital, Karlskrona between 26 January 1992 and 25 January 1996. Patients who presented to the emergency room (ER) with recent or ongoing chest pain were at this time by routine directly transferred to the coronary intensive care unit. Patients were included after written informed consent. Patients unable to give informed consent because of their medical condition were excluded. Of the total 5292 patient admissions included, 2992 were between 30 and 74 years of age at admittance. In patients with multiple admittances, only the first classifying admittance was included as a case in the study. The selection of patients for the current study is outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart outlining selection of patients for the current study. For patients with more than one hospital admittance during the study, only the first admittance under a classifying diagnosis was included in the current study. In total, 1136 patients ≥30 and <75 years were excluded. These represent either patients with known CAD (stable angina, previous MI, prior diagnosis of ischaemic heart failure, stroke) or patients included with a previous admission in either the ACS or non-ACS group. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHAPS, Carlscrona Heart Attack Prognosis Study; MI, myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

Patients with ACS

A diagnosis of ACS was ascertained in 908 eligible patients aged 30–74 years of age (644 men and 264 women). Two groups were identified: (1) patients experiencing at least one acute MI (AMI) during the study (527) or (2) patients experiencing no AMI, but having at least one episode of UA during the study (381). Data on environmental and lifestyle factors and blood samples were collected on first admittance under the classifying diagnosis. The classifying diagnosis was set at discharge by one of two experienced cardiologists.

A diagnosis of AMI was made when patients fulfilled at least two of the following criteria: (1) a history of chest pain of at least 15 min duration, (2) an increase in activity of cardiac biomarkers (aspartate aminotransferase and/or creatine kinase) to at least twice the upper limit of normality or (3) characteristic ECG changes for MI (typical sequence change of the ST segment and/or of T-waves and/or appearance of new Q-waves). These criteria included patients with ST-elevation MI (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI) corresponding to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 code 410.

A diagnosis of UA was made when patients fulfilled all of the following criteria: (1) no evidence of MI, (2) acute chest pain of increased/modified character to any previously experienced during the preceding 48 h and (3) angina pectoris diagnosed and medically treated before admission or, alternatively, angina pectoris ascertained by clinical evaluation, including a bicycle exercise test prior to discharge from the hospital. These patients correspond to ICD 9 code 411. Postinfarction angina and patients with secondary angina were not included.

Patients admitted to the coronary intensive care unit were initially treated with aspirin and, in case of ongoing chest pain, also nitrates and morphine. In cases of clear diagnosis of STEMI, thrombolysis with streptokinase was given (194 of 527 patients with MI). Patients with MI diagnosed by cardiac markers only were not given thrombolysis. At the time of the study, acute coronary artery intervention was not available at this hospital.

Patients without ACS

The study population also contained 948 patients aged 30–74 (569 men and 379 women) who were admitted with suspected ACS, but were subsequently diagnosed as non-ACS and, furthermore, were not diagnosed with stable CAD. This group constitutes patients with chest discomfort or chest pain without remaining suspicion of cardiac ischaemic origin, thus excluding ICD 9 codes 410–414. Patients with dyspepsia, lower airway infection or musculoskeletal origin of chest pain are found in this group; however, in many cases, no specific medical condition had been established on discharge from the coronary intensive care unit.

Risk factors

The presence of CAD risk factors were identified based on laboratory analyses, patient history and/or medical records. Samples for laboratory analysis were collected at hospital admission and were analysed by the in-house routine diagnostic laboratory. Smoking status was defined as current smoker or non-smoker. The term non-smoker included patients who quit smoking >1 month before admission. Information on medical history of hypertension and diabetes was recorded at admission and extracted from earlier medical files, and the diagnosis and information were also verified at the time of discharge from the hospital. Hypertension was defined as a physician's diagnosis prior to hospital admittance. In general, these patients were treated with blood pressure-lowering medications. Patients with a previous diagnosis of diabetes were grouped for analysis as follows: (1) diet treated only, (2) oral medication only or (3) insulin treated. In parallel, to identify patients with an impaired glucose homoeostasis who had evidence of acute and long-term insufficient glucose control, a laboratory-defined classification based on glucose ≥7.5 mM together with glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥5.5 was used. We had previously evaluated this classification by comparing with a prior diagnosis of DM and found that 89% of those treated by diet only, 95% of those treated by oral medication only and 100% of those treated with insulin were identified as having impaired glucose homoeostasis using this classification (unpublished).

Statistical methods

STATA and IBM SPSS Statistics were used for data analyses. Standard methods were used for descriptive statistics. Associations between categorical variables were examined using binary logistic regression and expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. Principal analyses were made with men and women combined in one group, but were repeated where men and women were analysed separately. Age was entered into the regressions in 10-year age groups. Confounding was considered by stratification for final diagnosis (as MI, ACS or not) and by multivariate regression models forcing age group, sex, impaired glucose homoeostasis, serum cholesterol, hypertension and current smoking into the same model. Individuals with a missing variable were excluded from the respective analysis. Two-way interaction terms were used to explore the association of sex and the major risk factors with an ACS outcome.

Results

Patient characteristics

CHAPS recruited 5292 patients of which 2992 were aged 30–74 years of age. Table 1 shows patient characteristics of the 908 eligible patients with ACS and the 948 eligible patients without ACS or any current or previous medical history of CAD (patients without ACS). Among patients with ACS, we identified 46 patients (5%) with no previous diagnosis of diabetes as having impaired glucose homoeostasis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Non-ACS |

MI |

UA |

Number of patients with data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Patients | 569 | 379 | 394 | 133 | 250 | 131 | 1856 |

| Age | 57.4 (11.2) | 60.1 (11.2) | 63.3 (8.6) | 65.8 (8.0) | 62.5 (8.7) | 65.1 (8.1) | 1856 |

| Smoking | 119 (24.4) | 48 (14.2) | 100 (27.0) | 29 (23.2) | 48 (19.8) | 14 (11.1) | 166 |

| Hypertension | 84 (17.0) | 77 (22.7) | 101 (26.8) | 32 (25.2) | 68 (27.9) | 39 (31.0) | 148 |

| Cholesterol* | 5.8 (1.4) | 6.1 (1.4) | 6.1 (1.3) | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.6 (1.3) | 822 |

| Diabetes all | 29 (5.9) | 30 (8.8) | 65 (17.2) | 28 (21.9) | 27 (11.1) | 22 (17.5) | 201 |

| DM (diet) | 24 (4.9) | 24 (7.0) | 48 (12.7) | 18 (14.1) | 22 (9.0) | 13 (10.3) | 149 |

| DM (p.o) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 11 (2.9) | 7 (5.5) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (2.4) | 28 |

| DM (insulin) | 3 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) | 6 (1.6) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (4.8) | 24 |

| Glucose* | 5.7 (2.6) | 6.7 (4.6) | 7.3 (3.8) | 8.1 (4.1) | 5.9 (2.3) | 6.4 (3.3) | 797 |

| HbA1c* | 4.6 (0.8) | 5.0 (1.5) | 5.3 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.7) | 5.1 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.6) | 833 |

| Glucose control† | 6 (4.3) | 9 (11.4) | 65 (18.6) | 33 (30.6) | 29 (13.3) | 18 (16.4) | 882 |

Data are means (SD) or numbers (%). DM (diet) no pharmacological treatment for diabetes, DM (p.o) oral medication for diabetes, DM (insulin) treatment included insulin.

*Routine laboratory analysis of admission samples.

†Glucose control defined as an impaired glucose homoeostasis by HbA1c ≥5.5%+glucose ≥7.5 mM.

DM, diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; MI, myocardial infarction; Non-ACS; non-acute coronary syndrome; UA, unstable angina.

Risk factors predisposing to MI in ACS

We tested the hypothesis that UA and MI are two separate outcomes in ACS, differently influenced by established risk factors for the underlying CAD. The results are shown in table 2. Current smoking (OR 2.42 (1.61 to 3.62)), an impaired glucose homoeostasis defined as glucose ≥7.5 mM and HbA1c ≥5.5% (OR 1.78 (1.19 to 2.67)) and male sex (OR 1.71 (1.21 to 2.40)) were found to be more strongly associated with MI, compared with UA. The same held true for age, although this was a weaker association (OR 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04)). Neither cholesterol (total cholesterol level) nor a previous diagnosis of hypertension was more strongly associated with MI than UA. These data indicate that different CAD risk factors are associated with different ACS outcomes.

Table 2.

The ORs of MI versus UA in patients with acute coronary syndromes

| MI vs UA |

||

|---|---|---|

| OR | CI (95%) | |

| Glucose control* | 1.78 | 1.19 to 2.67 |

| Age group† | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.04 |

| Sex (male) | 1.71 | 1.21 to 2.40 |

| Cholesterol | 1.06 | 0.94 to 1.19 |

| Smoking | 2.42 | 1.61 to 3.62 |

| Hypertension | 0.84 | 0.60 to 1.18 |

Associations were estimated by binary logistic multivariate regression and expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. MI versus UA was the dependent variable and age by 10 year age groups, sex, serum cholesterol, smoking, hypertension and glucose control were entered as covariates into the same model that included 742 participants.

*Impaired glucose homoeostasis (HbA1c ≥5.5%+blood glucose ≥7.5 mM).

†Age groups: 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–74 years.

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; MI, myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

Risk factors predisposing to MI or UA

Next, we compared the individual subgroups of patients with MI or UA with patients without ACS (table 3) to establish the association between the risk factors and the specific ACS outcome. Impaired glucose homoeostasis, male sex, cholesterol level and age group were significantly associated with MI and UA, when compared to patients without ACS. Interestingly, smoking was significantly associated only with MI (OR 2.00 (1.32 to 3.02)), but not with UA (OR 0.84 (0.53 to 1.33)).

Table 3.

The ORs of myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina (UA) versus patients without acute coronary syndrome (non-ACS)

| MI vs non-ACS |

UA vs non-ACS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI (95%) | OR | CI (95%) | |

| Glucose control* | 4.22 | 2.35 to 7.56 | 2.14 | 1.15 to 3.95 |

| Age group† | 1.06 | 1.04 to 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.03 to 1.06 |

| Sex (male) | 2.44 | 1.68 to 3.55 | 1.48 | 1.02 to 2.15 |

| Cholesterol | 1.17 | 1.03 to 1.32 | 1.15 | 1.00 to 1.32 |

| Smoking | 2.00 | 1.32 to 3.02 | 0.84 | 0.53 to 1.33 |

| Hypertension | 1.06 | 0.71 to 1.58 | 1.29 | 0.87 to 1.92 |

Associations were estimated by multivariate binary logistic regression and expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. MI and UA were the dependent variables and age by 10 year age groups, sex, serum cholesterol, smoking, hypertension and glucose control were entered as covariates into the same model. The number of patients included in final models was 680 (MI vs non-ACS) and 564 (UA vs non-ACS), respectively.

*Impaired glucose homoeostasis (glycated haemoglobin ≥5.5%+blood glucose ≥7.5 mM).

†Age groups: 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–74 years.

We found no statistically significant interactions between sex and any of the major risk factors for CAD in the association with the outcome of ACS. In sex-specific subanalyses, there was no significant difference between the results for men and women.

Discussion

In the current study, we show that an impaired glucose homoeostasis, smoking or male sex, in addition to being known major risk factors for CAD, is associated with a more severe outcome in the case of ACS (ie, they predispose to MI, rather than UA). Interestingly, when compared with the non-ACS group, smoking was significantly associated with MI, but not UA, suggesting that its effects are mainly important in the determination of the ACS outcome, rather than the development of all clinical manifestations of CAD per se.

The major strength, and novelty, of this study is due to the unique nature of the CHAPS patient cohort. Patients were recruited before the introduction of PCI, CABG and modern antithrombotic drugs in the standard management of ACS. The absence of these interventions, which would otherwise have influenced the thrombotic processes involved in ACS, made it possible to identify progression to UA or MI as distinct outcome groups within the cohort.

Furthermore, we were also able to gather information on patients without ACS who were admitted into the same hospital setting, during the same period. These patients were initially admitted with a suspected ACS diagnosis, but were discharged from the heart intensive unit after being assessed as not having experienced an ACS, or even suffering from stable CAD. Thus, the patients without ACS provided an excellent control group, as they had a similar initial management routine following ER presentation, that is, transfer to a coronary care unit for observation until an ACS diagnosis was confirmed or excluded. A major strength of our study results from its being based in a single centre with the same two cardiologists evaluating and categorising all patients, using consistent criteria and furthermore consistent management routines. This ensured a level of consistency that is not possible when using data from healthcare registry studies, which rely solely on diagnosis codes based on each treating physician’s judgement, and are composed of data from multiple hospitals and collected for purposes other than research.3 4

A number of limitations of the study should be acknowledged. Biochemical analyses were performed over a period of 4 years, although the hospital routine diagnostic laboratory used accredited standardised methods, providing consistency over time. Data for laboratory analyses were not complete for all patients. The definition of MI continues to evolve as refined criteria and more sensitive and specific biomarkers are implemented. Some of the UA cases in our study would most likely have now been diagnosed as NSTEMI, using recent criteria required for MI diagnosis.5 The control group is not representative of the general population as it is enriched for individuals seeking medical attention for non-coronary conditions presenting with chest pain or discomfort, of which some may also be associated with smoking (ie, dyspepsia, bronchitis). Furthermore, CHAPS is a single-centre study, and treatments and risk factor profiles have also partly developed since the study was performed. The results would therefore not necessarily be generalised to a broader modern population, although our results are supported by most recent studies as discussed below.4 6 However, smoking remains a major health issue and type 2 diabetes is increasing in the western society; therefore, the results are still highly relevant today for the care of patients with CAD.

The determining role of thrombotic factors in the outcome of an ACS is underscored by the success of more aggressive antithrombotic treatment in recent years.2 Previously, we have shown, using the CHAPS material, that genetic variations of thrombotic factors are associated with an ACS outcome.7 We show here that impaired glucose homoeostasis confers an increased risk towards MI, rather than UA, in an ACS. Diabetes has been associated with early and late mortality after presentation with an ACS,8 and furthermore, non-fasting elevated blood glucose has been associated with an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease and MI.9 One reason for a more adverse outcome in a patient with diabetes and/or impaired glucose homoeostasis could be due to a prothrombotic effect, as also indicated by the more salutary effects of antithrombotic treatment in patients with diabetes.10 In the present study, we used the laboratory-based combination of an increased blood level of glucose and HbA1c to ascertain an acute, as well as a more long-standing, deregulated glucose homoeostasis. Our finding that 46 of the patients with ACS, but no previously known diabetes, fulfilled these laboratory-based criteria is in line with previous reports of unknown diabetes in a significant proportion of patients with AMI.11

Our finding that current smoking is more common in patients with MI than in those with UA is supported by data from a recent registry-based longitudinal cohort study of patients with ACS in the National Swedish Quality-of-Care Register (Riks-HIA)4 and in the prospective population-based CAREMA cohort study.6 Interestingly, our finding that smoking was associated with MI, but not UA, when compared with the patients without ACS, shows that smoking has a significant effect mainly in the acute event, possibly through modulation of thrombogenicity at the site of a ruptured plaque.12 This is supported by the finding of Dudas et al13 that smoking was associated with MI but not with extensive CAD in need of a coronary bypass grafting. Furthermore, Björck et al14 found smoking to be an independent determinant for presenting with STEMI compared with NSTEMI in 93 416 consecutive patients aged 25–84 years and admitted to hospital between 1996 and 2004 with a first AMI. Previous reports show that the increased risk for MI associated with smoking decreases rapidly after cessation,12 15 16 supporting the idea that smoking is a critical risk factor in the acute stages of ACS, rather than in all clinical manifestations of CAD.

In conclusion, our study shows that the presence of known major risk factors for CAD, such as an impaired glucose homoeostasis, smoking and male sex, is also significantly associated with a more severe outcome in the case of an ACS. Our finding that current smoking is strongly associated with MI, but not UA, emphasises the importance of the clinical practice of encouraging current smokers with a diagnosis of CAD to quit their smoking habits.

The observed differences in ACS outcome associated with smoking or dysregulated glucose metabolism highlight several hypotheses that warrant further investigation. Establishing the influence of these risk factors at the cellular level, for example, on platelet function, coagulation and/or fibrinolysis, inflammation and other factors influencing the vessel micromilieu, could lead to optimisation of pharmacological treatment for CAD and ACS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Lynn Butler for valuable suggestions and comments on the manuscript. They also thank senior cardiology consultant Dr Per-Ola Bengtsson for evaluating and categorising the patients included in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LR, HO and MF designed and initiated the original Carlscrona Heart Attack Prognosis Study (CHAPS) on which the current study is based. MF conducted the patient inclusion, reviewed all cases, collected patient information and compiled the data files. JO, HF, IV, HO, AH, LR and UL conceived and designed the current study. IV and M-LP collected and compiled the laboratory data. HF and UL performed the statistical analyses and compiled the results. JO, MF, HF, IV, HO, AH, LR and UL interpreted the results. JO, HO and UL drafted the paper. MF, HF, IV and LR contributed to critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript. JO is the guarantor.

Funding: CHAPS has been supported by Blekinge County Council.

Competing interests: JO was funded by a grant from the Stockholm County Council.

Ethics approval: CHAPS was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Lund, Sweden (EPN 2009/762 and LU 298-91).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Libby P. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res 2009;50(Suppl):S352–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001;345:494–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrett E, Shah AD, Boggon R, et al. Completeness and diagnostic validity of recording acute myocardial infarction events in primary care, hospital care, disease registry, and national mortality records: cohort study. BMJ 2013;346:f2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudas K, Björck L, Jernberg T, et al. Differences between acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina: a longitudinal cohort study reporting findings from the Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions (RIKS-HIA). BMJ Open 2013;3:e002155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merry AH, Boer JM, Schouten LJ, et al. Smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and family history and the risks of acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina pectoris: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011; 11:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Odeberg J, Freitag M, Odeberg H, et al. Severity of acute coronary syndrome is predicted by interactions between fibrinogen concentrations and polymorphisms in the GPIIIa and FXIII genes. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:909–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marso SP, Safley DM, House JA, et al. Suspected acute coronary syndrome patients with diabetes and normal troponin-I levels are at risk for early and late death: Identification of a new high-risk acute coronary syndrome population. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:1931–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, McCarthy MI, et al. Nonfasting glucose, ischemic heart disease, and myocardial infarction: a Mendelian randomization study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59:2356–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roffi M, Eberli FR. Diabetes and acute coronary syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;23:305–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G, et al. Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus: a prospective study. Lancet 2002;359:2140–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1731–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudas KA, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Predictors of coronary bypass grafting in a population of middle-aged men. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:122–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Björck L, Rosengren A, Wallentin L, et al. Smoking in relation to ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: findings from the Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admissions. Heart 2009;95:1006–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sargent RP, Shepard RM, Glantz SA. Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study. BMJ 2004;328:977–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackay DF, Irfan MO, Haw S, et al. Meta-analysis of the effect of comprehensive smoke-free legislation on acute coronary events. Heart 2010;96:1525–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.