Abstract

Since higher plants regularly release organic compounds into the environment, their decay products are often added to the soil matrix and a few have been reported as agents of plant-plant interactions. These compounds, active against higher plants, typically suppress seed germination, cause injury to root growth and other meristems, and inhibit seedling growth. Mucuna pruriens is an example of a successful cover crop with several highly active secondary chemical agents that are produced by its seeds, leaves and roots. The main phytotoxic compound encountered is the non-protein amino acid L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), which is used in treating the symptoms of Parkinson disease. In plants, L-DOPA is a precursor of many alkaloids, catecholamines, and melanin and is released from Mucuna into soils, inhibiting the growth of nearby plant species. This review summarizes knowledge regarding L-DOPA in plants, providing a brief overview about its metabolic actions.

Keywords: Allelopathy, allelochemicals, L-DOPA, plant growth, Mucuna, reactive oxygen species, non-protein amino acid

Plants that live in a community compete among themselves for soil resources such as water and nutrients.1 As plants are sessile organisms and cannot “relocate,” when environmental conditions become unfavorable they adopt another survival strategy, allelopathy. This ecological phenomenon consists of the release of chemical compounds (allelochemicals) into the environment that can influence the growth and development of neighboring plants, both positively and negatively.2 Therefore, allelopathy constitutes a chemical contribution to the adaptation of plants to the environment. Allelochemicals can be classified as terpenoids, nitrogen-containing compounds and phenolic compounds.3 Here we are most interested in nitrogen-containing compounds with allelopathic potential, and more specifically about the non-protein amino acid L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA).

Plants produce hundreds of non-protein amino acids, among which L-DOPA,4 a compound with strong allelopathic activity, stands out. This allelochemical is found in large quantities (1% and 4–7% in the leaves and seeds, respectively)5 in velvet bean [Mucuna pruriens (L.) var. utiliz], a legume of the Fabaceae family that has a nutritional quality comparable to the soybean.6 Velvet bean is often used for soil cover and as silage due to the large amount of organic matter with high digestibility it produces. It is estimated that velvet bean can release about 100–450 kg ha−1 of L-DOPA into the soil. Furthermore, its ability to control weeds and nematodes greatly reduces the need to apply artificial chemicals to the crops.5,7,8 In addition, its cultivation in tropical areas is aimed at enriching the soil due to its ability to fix nitrogen.9 Velvet bean has been intercropped with maize and rice in Nigeria and Japan, respectively. In one study, an increase in rice production after the use of velvet bean as a cover crop was observed.10 Additionally, an increase in yield and a decrease in weed infestation have been observed in maize-velvet bean rotations.11,12 Its allelopathic and nitrogen-fixation properties appear to be responsible for these effects.

L-DOPA has attracted much attention due to its preventive action against Parkinson disease, characterized by a deficiency in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter dopamine in nerve cells. In contrast to dopamine, L-DOPA can cross the hematoencephalic barrier and enter into nerve cells, where it is decarboxylated to dopamine. In cells, L-DOPA can also be oxidized toward melanin, producing leucodopachrome and dopachrome by auto-oxidation or with the aid of tyrosinases, also known as polyphenol oxidases (PPO). During these reactions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion (O2•-) and hydroxyl radical (HO•) can be produced. Some studies report that the beneficial effect of L-DOPA on Parkinson disease is counterbalanced by the strong oxidative damage generated over a long period of drug administration.13-16

L-DOPA has also been found at high levels in fava bean (Vicia faba L.), one of the oldest crops in Europe, traditionally used as weld beans for animal feed and human food, and as broad beans for direct human consumption. The content and distribution of this non-protein amino acid were examined in cotyledons and embryo axis along the germination and seedling growth of Vicia faba varieties Alameda and Brocal. L-DOPA was augmented in embryo axis along the germination, with the highest content being observed in the Brocal variety 6 d after imbibition. Thus, the embryo axis of fava bean seedlings can be considered a good natural source of L-DOPA.17 The compound is found in significant quantities in the vacuoles of fava bean leaves, as H2O2 formed in the chloroplasts diffuses into the vacuoles. Vacuolar peroxidase (POD) also oxidizes L-DOPA to dopachrome and other compounds such as melanin.18

L-DOPA Metabolic Pathway

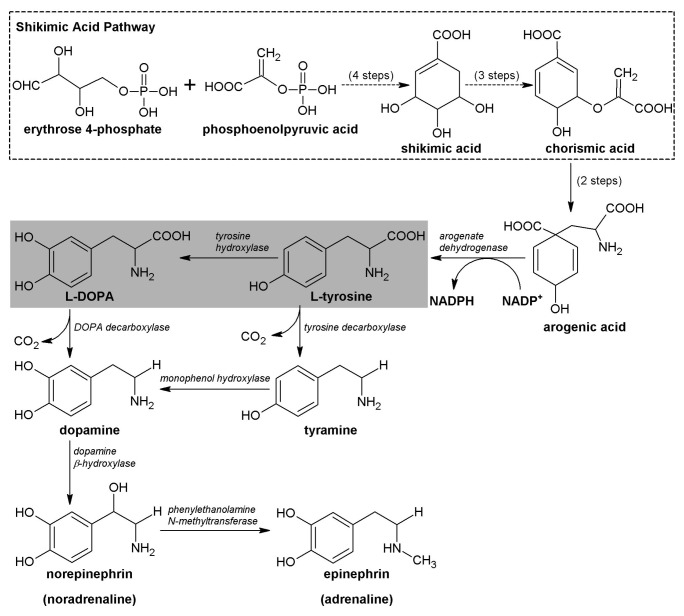

The shikimic acid pathway converts simple carbohydrate precursors derived from glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway to the aromatic amino acids tyrosine, phenylalanine, tryptophan and it participates in the biosynthesis of most plant phenolics. One of the intermediaries on this route is shikimic acid (Fig. 1), which gives its name to this sequence of reactions.3 L-DOPA is a catecholamine whose formation is a result of the hydroxylation of tyrosine, and is a precursor of neurologically important molecules such as the neurotransmitters dopamine, adrenaline and noradrenaline. As aforementioned, L-DOPA is also an essential precursor in the biosynthesis of melanin, which is present in many tissues from animals and plants. The main path to L-DOPA formation is via hydroxylation of tyrosine residues by the copper-containing enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase in the company of molecular O2. The L-DOPA synthesis pathway in plants is analogous to that in mammals. The compound can also suffer decarboxylation by tyrosine decarboxylase, resulting in tyramine synthesis. Dopamine is produced via hydroxylation of tyramine or decarboxylation of L-DOPA, and dopamine hydroxylation leads to norepinephrine production (Fig. 1), which in turn is methylated to give rise to epinephrine (adrenaline).19-21

Figure 1. L-DOPA metabolic pathway

L-DOPA as an Allelochemical

Due to their sessile way of life, plants rely upon the release of chemical compounds as a main defense strategy, among which stand out cyanogenic glycosides, glucosinolates, alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, latex and protease inhibitors.22,23 Non-protein amino acids accumulate massively in many plants and seem to play an important role in resistance to herbivores.24 Velvet bean seeds, as aforementioned, are known to accumulate large amounts of L-DOPA and are not attacked by small mammals or insects, suggesting a feeding repellent property. Southern armyworm larvae fed a diet containing seeds of velvet bean or synthetic L-DOPA showed an increased mortality.25 The number of abnormal pupae and adults was also higher after L-DOPA treatment. Alternatively, non-protein amino acids can also be a carbon/nitrogen reserve not metabolizable by herbivores.26

This compound is exuded from the roots, where its concentration can reach 1 ppm in water-culture solution and 50 ppm in the immediate vicinity of the roots. This concentration is high enough to reduce the growth of neighboring plants. This growth inhibition can even be seen in agar-medium culture in a mixed culture.27 Investigations into the kinetics of turnover of L-DOPA, l-phenylalanine and l-tyrosine in a volcanic ash soil, at various pH values, showed that l-phenylalanine and l-tyrosine were not adsorbed and transformed in the soil at equilibrium pH values between 4 and 7, in contrast to L-DOPA. These results suggest that the adsorption and transformation reactions of L-DOPA in the soil involve the catechol moiety. Thus, the concentrations of allelochemicals bearing a catechol moiety in soils may decrease rapidly owing to adsorption and transformation reactions, and this decrease will be faster in soils with a high pH or high adsorption ability, which can result in a reduction in its plant-growth-inhibitory activity.28

Effects of L-DOPA in Plants

A study of the effects of L-DOPA on different plant species revealed that it has the attributes of a typical allelochemical.29 These authors observed a variety of responses by plants to L-DOPA. For example, Gramineae and Leguminosae species were less affected, with respect to root growth, than species of Brassicaceae, Compositae, Cucurbitaceae and Hydrophyllaceae. These results demonstrated that L-DOPA is a powerful allelochemical, considering that the concentrations required to cause 50% inhibition (EC50) ranged from 5 to 50 mg/mL. In addition to possibily affecting the growth of various plants, especially root growth, another aspect to be highlighted is the ability of these plants to detoxify L-DOPA. During this process, it can be decarboxylated to form dopamine by the action of L-DOPA decarboxylase, or form 3-O-methyldopa through the action of catechol-O-methyltransferase.30

The herbicidal effects of L-DOPA have been investigated on weed species such as wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis), creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense), field poppy (Papaver rhoeas) and henbit (Lamium amplexicaule), using wheat (Triticum vulgare) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) species as control plants. L-DOPA showed a suppressive herbicidal effect on the weeds at concentrations of 1500 and 3000 mg/L without significantly affecting wheat and barley growth. Inhibition of root growth was more prominent compared with shoot growth.31 In studies with lettuce and chickweed, L-DOPA suppressed radicle growth in both by 50% compared with the control at 50 ppm; however, it exerted less of an effect upon hypocotyl growth and was virtually ineffective with regard to germination.8

Soares et al.2 reported that L-DOPA was effectively absorbed by soybean, inhibited root growth and increased the contents of tyrosine and phenylalanine. In this plant, L-DOPA could have been detoxified toward phenylalanine, providing a substrate for phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), the first enzyme of the phenylpropanoid pathway. This was corroborated by increases in phenolic compounds, lignin content and the activities of related enzymes such as PAL, cell wall bound POD, and cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD). CAD is considered a marker of lignification32 and plays an important role in the synthesis of monolignols in the cell wall.33 Thus, Soares et al.2,34 suggested that L-DOPA can be associated with its effects on the phenylpropanoid pathway, which activates the production of lignin and reduces soybean root growth. In this context, Siqueira-Soares et al.35 reported that the growth of the maize roots, the soluble cell wall-bound POD, PAL and tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) activities decreased, although tyrosine, phenylalanine and lignin levels increased after exposure to L-DOPA. These authors propose that the inhibition of PAL and TAL can amass tyrosine and phenylalanine. A possible incorporation of these amino acids into the cell wall can increase the occurrence of unusual monomers followed by lignin deposition. Therefore, the cell growth is limited and the root development is reduced.

As aforementioned, dopaquinone is generated by PPO reaction during the oxidation of L-DOPA to melanin. Increases in PPO activity and decreases in lipid peroxidation were observed in cucumber plants exposed to L-DOPA,36 results also noted by Soares et al.37 in soybean roots. The reduction in lipid peroxidation may be related to the activity of antioxidant enzymes and/or suppression of ROS generation by quinoprotein formation. These proteins can be produced by reaction between dopaquinone and the sulfhydryl groups of proteins and can cause damage to cells such as enzyme deactivation, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA fragmentation, and apoptosis.36,38 L-DOPA has also shown activity as an inhibitor of electron transport in the respiratory chains of plants and animals.39

In Arabidopsis, L-DOPA altered the expression of genes associated with the responses of plant to biotic and abiotic stresses. A microarray analysis showed that L-DOPA treatment increased and reduced the expression of 110 and 69 genes, respectively. At least 10 upregulated genes encoding for ion transporters (Zn, Cu, Fe) are associated with metal homeostasis. Two upregulated genes were found to be related to osmotic stress. Additionally, the authors observed changes in the expression of genes involved in amino acid metabolism, oxidative stress, melanin synthesis and lignification. The authors suggested that the mode of action of L-DOPA may be related to changes in amino acid metabolism and iron homeostasis, important for many fundamental biological processes such as photosynthesis.40

Additionally, L-DOPA also seems to mimic amino acid analogs, with subsequent incorporation into proteins.26 In fact, the binding of L-DOPA to tyrosyl and phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetases has been observed in bacterial and prokaryotic-eukaryotic cells, respectively,41 including mammalian cells in vitro.42-44 Furthermore, an increased level of protein-incorporated L-DOPA was observed in lymphocyte cell proteins of a Parkinson patient treated with this compound. Thus, the incorporation of this “non-protein” amino acid in proteins of susceptible species can at least be suggested as a mechanism of their toxicity.43

L-DOPA: Pro-oxidant or Antioxidant?

Pro-oxidant properties

Studies have reported that ROS can be generated during the biosynthesis of melanin initiated by a cascade of L-DOPA auto-oxidation.45-48 These reactions occur without enzymatic catalysis, but the rate is increased in the presence of trace concentrations of metal ions (Fe3+ and Cu2+). The loss of an electron from L-DOPA produces the semiquinone radical DOPA-SQ–. This may be oxidized to dopaquinone (DOPA-Q), which is an intermediate in the L-DOPA oxidation pathway.49,50 DOPA-Q can also be generated by the direct loss of two electrons from L-DOPA by enzymatic reaction. In this way, it has been proposed that the oxidation of L-DOPA may result in damage to other molecules through either direct or indirect responses. DOPA-SQ– can transfer electrons to other molecules, or remove hydrogen atoms. Indirect damage may occur by production of ROS, direct reduction of peroxides or via reduction of molecular O2 to O2•– and subsequent dismutation to H2O2 species. In the presence of certain transition metal ions, H2O2 can form HO• radicals. DOPA-Q can be oxidized and the products of this process are indole compounds, which can undergo further reactions to form melanin (Fig. 2). In addition, the rate of oxidation of L-DOPA is markedly pH-dependent. Under acidic conditions L-DOPA is relatively stable, whereas at physiological pH oxidation takes place in a few hours, and in a basic solution oxidation is very rapid.48

Figure 2. L-DOPA oxidation

Other studies have shown that incubation of L-DOPA and its oxidation products with proteins (e.g., creatine kinase) in the presence of Fe3+ can result in the generation of DOPA-SQ- radicals. The radical formation can occur via multiple mechanisms, including the removal of hydrogen atoms from proteins by DOPA-SQ–, and may lead to enzyme inhibition.48 Inactivation mediated by SH group oxidation at the active site of the enzyme by DOPA-SQ– was proposed by Takasaki and Kawakishi.51 The ROS also generated during L-DOPA oxidation can also cause severe damage to cell proteins. For example, the iron/sulfur complexes of metalloproteins, particularly Fe-S enzymes as aconitase and fumarase, are rapidly destroyed by O2•– with inactivation of the enzymes.52 H2O2 reversibly inhibits various enzymes in the carbon fixation cycle and other metabolic pathways by oxidizing thiol functional groups, and is also capable of causing peroxidation of lipids and pigments.53

As mentioned above, L-DOPA can be oxidized toward melanin. In this context, studies have shown that exposure to L-DOPA led to a greater accumulation of melanin in lettuce than in barnyard grass.45 Additionally, lettuce plants also showed higher PPO activity, an enzyme involved in the oxidation of L-DOPA. According to the authors, the mechanism of tolerance in barnyard grass seems to be related to the metabolic destiny of the L-DOPA. In barnyard grass, this compound is metabolized to phenylalanine, tyrosine, and dopamine, which was not observed in lettuce.47 This reduces ROS formation and, consequently, membrane damage caused by lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, the application of an exogenous antioxidant agent (ascorbic acid) decreased PPO activity and lipid peroxidation, and reversed the growth-inhibition caused by L- DOPA in lettuce.45 In this context, Soares et al.37 reported that L-DOPA (0.1–1.0 mM) increased PPO activity and melanin synthesis (roots become black) in soybean. The results showed that the increase in the PPO activity was associated with the browning root, suggesting that melanin synthesis came from the oxidation of L-DOPA.

Antioxidant properties

L-DOPA seems to possess contradictory characteristics with respect to the formation of ROS. Some studies have reported an antioxidant activity of L-DOPA.54-58 It is well known that antioxidants are a heterogeneous group of substances comprised of vitamins, minerals, natural pigments and other plant compounds. The term antioxidant means “that prevents the oxidation of other chemicals”59 that otherwise occur in metabolic reactions or due to exogenous factors such as ionizing radiation.

In an attempt to elucidate the potential differences between antioxidant phenolic acids, Marinova and Yanishlieva60 performed a quantitative comparison of the kinetic behavior of the oxidation inhibition of several benzoic acids (p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic, syringic, and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic) and cinnamic acids (p-coumaric, ferulic, caffeic and sinapic). The authors reported that a higher antioxidant activity was found when there are two hydroxyl groups in positions 3 and 4, as in the structures of caffeic acid and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid. Importantly, L-DOPA has the structure of a phenolic acid, similar to caffeic acid, differing only in the presence of an amino group in the aliphatic chain of the latter.

As described previously, it is known that L-DOPA is the main phenolic of the seeds of Mucuna spp. Rajeshwar et al.61 tested the antioxidant activity of a seed extract of Mucuna pruriens. They noted that Mucuna extract showed strong antioxidant activity by decreasing the concentrations of the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH•) radical and ROS, including nitric oxide (NO), when compared with different standards such as the antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), L-ascorbic acid, curcumin, quercetin and α-tocopherol. However, the components responsible for the antioxidant activity were not isolated and identified.

It has also been suggested that L-DOPA seems to possess both pro-oxidant and antioxidant activities depending on the concentration used. For example, the addition of low concentrations of L-DOPA with iron chelates and H2O2 increased HO• radical production; however, high concentrations of L-DOPA inhibited the formation of HO• radicals.54 L-DOPA also demonstrated antioxidant activity in different in vitro assays, including elimination of DPPH•, ROS, and lipid peroxidation. It exhibited antioxidant activity comparable to that of standards such as butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), BHT, the natural antioxidant α-tocopherol, and trolox. L-DOPA inhibited lipid peroxidation 68%. Moreover, BHA, BHT, α-tocopherol and trolox were inhibited by 74.4, 71.2, 54.7 and 20.1%, respectively.62

Soybean plants exposed L-DOPA also showed strong reductions in their ROS content. This has been attributed to increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) and POD activities, enzymes considered as ROS-scavengers, and also due to a possible direct antioxidant activity of L-DOPA.37 In addition, the consumption of H2O2 during lignification might have contributed to reducing the levels of this ROS, since L-DOPA increases lignification in soybean.34 The decreases in ROS contents were corroborated by reductions in lipid peroxidation; thus, Soares et al.37 suggests that the phytotoxicity of L-DOPA in soybean is not due to ROS production during its detoxification to melanin. To the contrary, at least under the conditions and concentrations tested, L-DOPA seems to have an antioxidant role in soybean roots, reducing the levels of ROS.

As noted, studies on the action of L-DOPA, its absorption by roots, and its effects on cellular metabolism are, indubitably, fascinating subjects. The variability in the responses and the controversial effects on the species studied are points that challenge researchers searching to understand the mode of action of this compound. Thus, the current review provides a brief overview about L-DOPA in plants, and contributes to enriching research into the physiology and biochemistry of plants. In breef, additional efforts are required to provide a working model for the role of L-DOPA as an allelochemical.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Rizzardi MA, Fleck NG, Vidal RA Jr.. . AM, Agotinetto D. Competition between weeds and crops by soil resources. Ciência Rural 2001; 31:707 - 14; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1590/S0103-84782001000400026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soares AR, Rita de Cássia S-S, Salvador VH, Maria de Lourdes LF. . Osvaldo Ferrarese-FilhoThe effects of L-DOPA on root growth, lignification and enzyme activity in soybean seedlings. Acta Physiol Plant 2012; 34:1811 - 7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11738-012-0979-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taiz L, Zeiger E. Plant Physiology. Sinauer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agostini-Costa TdS. Vieira RF, Bizzo HR, Silveira D, Gimenes MA. Secondary metabolites. In: Dhanarasu S, ed. Chromatography and its application: InTech, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishihara E, Parvez MM, Araya H, Kawashima S, Fujii Y. . L-3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)alanine (L-DOPA), an allelochemical exuded from velvetbean (Mucuna pruriens) roots. Plant Growth Regul 2005; 45:113 - 20; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10725-005-0610-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugalenthi M, Vadivel V, Siddhuraju P. . Alternative food/feed perspectives of an underutilized legume Mucuna pruriens var. utilis--a review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2005; 60:201 - 18; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11130-005-8620-4; PMID: 16395632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas-Ayala R, Rodrigues-Kabana R, Morgan-Jones G, McInroy JA, Kloepper JW. . Shifts in soil microflora induced by velvetbean (Mucuna deeringiana) in cropping systems to control root-knot nematodes. Biol Control 2000; 17:11 - 22; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bcon.1999.0769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujii Y. . Allelopathy in the natural and agricultural ecosystems and isolation of potent allelochemicals from Velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens) and Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa). Biol Sci Space 2003; 17:6 - 13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2187/bss.17.6; PMID: 12897455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anaya AL. . Allelopathy as a tool in the management of biotic resources in aroecosystems. Crit Rev Plant Sci 1999; 18:697 - 738; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/07352689991309450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farooq M, Jabran K, Cheema ZA, Wahid A, Siddique KHM. . The role of allelopathy in agricultural pest management. Pest Manag Sci 2011; 67:493 - 506; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ps.2091; PMID: 21254327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shave PA, Ter-Rumum A, Enoch MI. . Effects of time of intercropping of mucuna (Mucuna cochinchinensis) in maize (Zea mays) for weed and soil fertility management. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2012; 14:469 - 772 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adediran JA, Akande MO, Oluwatoyinbo FI. . Effect of mucuna intercropped with maize on soil fertility and yield of maize. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science 2004; 37:15 - 22 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park KH, Park HJ, Shin KS, Choi HS, Kai M, Lee MK. . Modulation of PC12 cell viability by forskolin-induced cyclic AMP levels through ERK and JNK pathways: an implication for L-DOPA-induced cytotoxicity in nigrostriatal dopamine neurons. Toxicol Sci 2012; 128:247 - 57; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/toxsci/kfs139; PMID: 22539619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emdadul Haque M, Asanuma M, Higashi Y, Miyazaki I, Tanaka K, Ogawa N. . Apoptosis-inducing neurotoxicity of dopamine and its metabolites via reactive quinone generation in neuroblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003; 1619:39 - 52; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0304-4165(02)00440-3; PMID: 12495814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basma AN, Morris EJ, Nicklas WJ, Geller HM. . L-dopa cytotoxicity to PC12 cells in culture is via its autoxidation. J Neurochem 1995; 64:825 - 32; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64020825.x; PMID: 7830076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng N, Maeda T, Kume T, Kaneko S, Kochiyama H, Akaike A, Goshima Y, Misu Y. . Differential neurotoxicity induced by L-DOPA and dopamine in cultured striatal neurons. Brain Res 1996; 743:278 - 83; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-8993(96)01056-6; PMID: 9017256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyoaga C, Burbano C, Cuadrado C, Varela A, Guillamón E, Pedrosa MM, et al. . Content and distribution of vicine, convicine and L-DOPA during germination and seedling growth of two Vicia faba L. varieties. Eur Food Res Technol 2008; 227:1537 - 42; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00217-008-0876-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albrecht C, Kohlenbach HW. . L-DOPA content, peroxidase activity, and response to H2O2 of Vicia faba L. and V. narbonensis L. in situ and in vitro. Protoplasma 1990; 154:144 - 50; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF01539841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulma A, Szopa J. . Catecholamines are active compounds in plants. Plant Sci 2007; 172:433 - 40; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.10.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong KH, Lee JL, Park HJ, Cho SH. . Purification and characterization of the tyrosinase isozymes of pine needles. Biochem Mol Biol Int 1998; 45:717 - 24; PMID: 9713694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiner U, Schliemann W, Strack D. . Assay for tyrosine hydroxylation activity of tyrosinase from betalain-forming plants and cell cultures. Anal Biochem 1996; 238:72 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/abio.1996.0253; PMID: 8660589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoonhoven LM. Loon JJAv, Dicke M. Insect-plant biology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mithöfer A, Boland W. . Plant defense against herbivores: chemical aspects. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2012; 63:431 - 50; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103854; PMID: 22404468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fürstenberg-Hägg J, Zagrobelny M, Bak S. . Plant defense against insect herbivores. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14:10242 - 97; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms140510242; PMID: 23681010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rehr SS, Janzen DH, Feeny PP. . L-dopa in legume seeds: a chemical barrier to insect attack. Science 1973; 181:81 - 2; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.181.4094.81; PMID: 17769830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang T, Jander G, de Vos M. . Non-protein amino acids in plant defense against insect herbivores: representative cases and opportunities for further functional analysis. Phytochemistry 2011; 72:1531 - 7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.03.019; PMID: 21529857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii Y, Shibuya T, Yasuda T. . L-3, 4-dihydroxyphenylalanine as an allelochemical candidate from Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. var.utilis. Agric Biol Chem 1991; 55:617 - 8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1271/bbb1961.55.617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furubayashi A, Hiradate S, Fujii Y. . Role of catechol structure in the adsorption and transformation reactions of L-DOPA in soils. J Chem Ecol 2007; 33:239 - 50; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10886-006-9218-5; PMID: 17195117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishihara E, Parvez MM, Araya H, Fujji Y. . Germination growth response of different plant species to the allelochemical L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA). Plant Growth Regul 2004; 42:181 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/B:GROW.0000017483.76365.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Offen D, Panet H, Galili-Mosberg R, Melamed E. . Catechol-O-methyltransferase decreases levodopa toxicity in vitro. Clin Neuropharmacol 2001; 24:27 - 30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00002826-200101000-00006; PMID: 11290879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topal S, Kocaçalişkan I. . Allelopathic effects of DOPA against four weed species. DPÜ Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü 2006; 11:27 - 32 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M. . Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2003; 54:519 - 46; PMID:14503002 http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Wang G, Chang J, Liu J, Cai J, Rao X, et al. . Effects of 1-MCP and ethylene on expression of three CAD genes and lignification in stems of harvested Tsai Tai (Brassica chinensis). Food Chem 2010; 123:32 - 40; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soares AR, Ferrarese MdeL, Siqueira RdeC, Böhm FMLZ, Ferrarese-Filho O. . L-DOPA increases lignification associated with Glycine max root growth-inhibition. J Chem Ecol 2007; 33:265 - 75; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10886-006-9227-4; PMID: 17195115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rita de Cássia S-S, Soares AR, Parizotto AV, Maria de Lourdes LF, Ferrarese-Filho O. Root growth and enzymes related to the lignification of maize seedlings exposed to the allelochemical L-DOPA. Sci World J 2013; 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mushtaq MN, Sunohara Y, Matsumoto H. . Bioactive L-DOPA induced quinoprotein formation to inhibit root growth of cucumber seedlings. J Pest Sci 2013; 38:68 - 73; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1584/jpestics.D13-005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soares AR, de Lourdes Lucio Ferrarese M, de Cássia Siqueira-Soares R, Marchiosi R, Finger-Teixeira A, Ferrarese-Filho O. . The allelochemical L-DOPA increases melanin production and reduces reactive oxygen species in soybean roots. J Chem Ecol 2011; 37:891 - 8; PMID:21710366 http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10886-011-9988-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jana S, Sinha M, Chanda D, Roy T, Banerjee K, Munshi S, Patro BS, Chakrabarti S. . Mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by quinone oxidation products of dopamine: Implications in dopamine cytotoxicity and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1812:663 - 73; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.013; PMID: 21377526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mushtaq MN, Sunohara Y, Matsumoto H. . Allelochemical L-DOPA induces quinoprotein adducts and inhibits NADH dehydrogenase activity and root growth of cucumber. Plant Physiol Biochem 2013; 70:374 - 8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.06.003; PMID: 23831820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golisz A, Sugano M, Hiradate S, Fujii Y. . Microarray analysis of Arabidopsis plants in response to allelochemical L-DOPA. Planta 2011; 233:231 - 40; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00425-010-1294-7; PMID: 20978802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Högenauer G, Kreil G, Bernheimer H. . Studies on the binding of DOPA (3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine) to tRNA. FEBS Lett 1978; 88:101 - 4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80617-6; PMID: 346372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunlop RA, Rodgers KJ, Dean RT. . Recent developments in the intracellular degradation of oxidized proteins. Free Radic Biol Med 2002; 33:894 - 906; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00958-9; PMID: 12361801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodgers KJ, Hume PM, Dunlop RA, Dean RT. . Biosynthesis and turnover of DOPA-containing proteins by human cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2004; 37:1756 - 64; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.009; PMID: 15528035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodgers KJ, Shiozawa N. . Misincorporation of amino acid analogues into proteins by biosynthesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008; 40:1452 - 66; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.009; PMID: 18329946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hachinohe M, Matsumoto H. . Mechanism of selective phytotoxicity of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (l-dopa) in barnyardgrass and lettuce. J Chem Ecol 2007; 33:1919 - 26; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10886-007-9359-1; PMID: 17899281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hachinohe M, Matsumoto H. . Involvement of reactive oxygen species generated from melanin synthesis pathway in phytotoxicty of L-DOPA. J Chem Ecol 2005; 31:237 - 46; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10886-005-1338-9; PMID: 15856781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hachinohe M, Sunohara Y, Matsumoto H. . Absorption, translocation and metabolism of DOPA in barnyardgrass and letucce: their involvement in species-selective phytotoxic action. Plant Growth Regul 2004; 43:237 - 43; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/B:GROW.0000045996.72922.1b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pattison DI, Dean RT, Davies MJ. . Oxidation of DNA, proteins and lipids by DOPA, protein-bound DOPA, and related catechol(amine)s. Toxicology 2002; 177:23 - 37; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00193-2; PMID: 12126793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Brien PJ. . Molecular mechanisms of quinone cytotoxicity. Chem Biol Interact 1991; 80:1 - 41; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90029-7; PMID: 1913977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolton JL, Trush MA, Penning TM, Dryhurst G, Monks TJ. . Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem Res Toxicol 2000; 13:135 - 60; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/tx9902082; PMID: 10725110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takasaki S, Kawakishi S. . Formation of protein-bound 3,4-dihydroxyphenilalanine and 5-S-Cysteinyl-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine as new cross-linkers in gluten. J Agric Food Chem 1997; 45:3472 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf9701594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asada K. . The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 1999; 50:601 - 39; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.601; PMID: 15012221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dietz KJ. . Plant peroxiredoxins. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2003; 54:93 - 107; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134934; PMID: 14502986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spencer JP, Jenner A, Butler J, Aruoma OI, Dexter DT, Jenner P, Halliwell B. . Evaluation of the pro-oxidant and antioxidant actions of L-DOPA and dopamine in vitro: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Free Radic Res 1996; 24:95 - 105; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/10715769609088005; PMID: 8845917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ham SS, Kim DH, Lee SH, Kim YS, Lee CS. . Antioxidant effects of serotonin and L-DOPA on oxidative damages of brain synaptosomes. Kor J Physiol Pharmacol 1999; 3:147 - 55 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camp DM, Loeffler DA, LeWitt PA. . L-DOPA does not enhance hydroxyl radical formation in the nigrostriatal dopamine system of rats with a unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesion. J Neurochem 2000; 74:1229 - 40; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741229.x; PMID: 10693956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Randhir R, Vattem DA, Shetty K. . Antioxidant enzyme response studies in H2O2 stressed porcine muscle tissue following treatment with fava bean sprout extract and L-DOPA. J Food Biochem 2006; 30:671 - 98; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2006.00090.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agil A, Durán R, Barrero F, Morales B, Araúzo M, Alba F, Miranda MT, Prieto I, Ramírez M, Vives F. . Plasma lipid peroxidation in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Role of the L-dopa. J Neurol Sci 2006; 240:31 - 6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.016; PMID: 16219327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Clarendon Press (Oxford and New York), 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marinova EM, Yanishlieva NV. . Inhibited oxidation of lipids II: comparison of the antioxidative properties of some hydroxy derivatives of benzoic and cinnamic acids. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 2004; 94:428 - 32 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajeshwar Y, Senthil KGP, Gupta M, Mazumder UK. . Studies on in vitro antioxidant activities of methanol extract of Mucuna pruriens (fabaceae) seeds. Eur Bull Drug Res 2005; 13:31 - 9 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gülçin I. . Comparison of in vitro antioxidant and antiradical activities of L-tyrosine and L-Dopa. Amino Acids 2007; 32:431 - 8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00726-006-0379-x; PMID: 16932840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]