Abstract

Many of the plant microRNA (miRNA) genes contain introns. The miRNA-containing hairpin loop structure is predominantly located within the first exon of such pri-miRNAs. We have shown that the downstream intron and its splicing are important for the regulation of the processing of these pri-miRNAs. The 5′ splice site in MIR genes is essential in the process of miRNA biogenesis. We postulate that the presence of yet undefined interactions between U1 snRNP and the pri-miRNA processing machinery leads to an increase in the efficiency of miRNA biogenesis. The 5′ splice site also decreases the accessibility of the polyadenylation machinery to the pri-miRNA polyA signal located within the same intron. It is likely that the spliceosome assembly controls the length and structure of MIR primary transcripts, and regulates mature miRNA levels. The emerging picture shows that introns, splicing, and/or alternative splicing have highly relevant roles in regulating the miRNA levels in very specific conditions that contribute to proper plant response to stress conditions.

Keywords: plant microRNA biogenesis, intron-containing pri-miRNAs, splicing, polyadenylation

Overview of microRNA biogenesis

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small RNA molecules (20–24 nt) that have key roles in the regulation of eukaryotic gene expression.1-5 MiRNAs act posttranscriptionally by targeting the effector complex called RISC (RNA Induced Silencing Complex) to a complementary mRNA, leading to its slicing or translation inhibition.6-8 The final output of miRNA activity is the downregulation of a given protein expression.

In animals, the primary precursors of miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) are partially processed in the nucleus by a multiprotein complex called the Microprocessor, in which Drosha exhibits RNase III-type activity that generates stem-loop pre-miRNAs, which are exported to the cytoplasm.9,10 There, another RNase III-type enzyme called Dicer recognizes and binds pre-miRNAs, and by specific cleavages produces miRNA/miRNA* duplexes. MiRNA strands of these duplexes are then loaded into the RISC complex in the cytoplasm.11,12 In contrast, biogenesis of plant miRNAs occurs exclusively in the nucleus where transcription and processing leading to the formation of miRNA/miRNA* duplexes takes place. A single RNase III-type enzyme, DCL1, is responsible in plants for the conversion of pri-miRNAs into miRNA/miRNA* duplexes. The exportin protein HASTY (HST) is thought to directly export miRNA/miRNA* duplexes from the nucleus to the cytoplasm where miRNAs will then be loaded into RISC complexes, and the complementary miRNAs* will be degraded.13-15

The comparison of animal and plant miRNA biogenesis shows that different miRNA intermediates are exported in both cases from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Another difference concerns pri-miRNA processing: While the production of stem-loop pre-miRNAs and miRNA/miRNAs* are performed in animals by 2 different enzymes located in separated compartments, in plants their production in the nucleus involves a single RNase III endonuclease: DICER-LIKE 1 (DCL1).16,17

Plant miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA Polymerase II. Pri-miRNAs, like all other RNA Polymerase II transcripts, contain a cap structure and a polyA tail at their 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively.18 The cap structure is recognized and bound by a specific Cap-Binding Protein Complex (CBC) that is formed by 2 proteins: the Cap-Binding Protein 20 (CBP20) and the Cap-Binding Protein 80 (CBP80), also known as the Abscisic Acid Hypersensitive 1 protein (ABH1).19,20 The CBC is known to influence the splicing efficiency of the first intron of pre-mRNAs, as well as the pattern of pre-mRNA alternative splicing.21 It has also been shown that the lack of either of these proteins impairs the biogenesis of certain miRNAs.22,23 A very specific feature of pri-miRNAs is the formation of a stem-loop structure in which miRNA and complementary miRNA* are embedded. DCL1 interacts with SERRATE (SE) and HYPONASTIC LEAVES 1 (HYL1), forming the plant microprocessing complex.24-26 SE cooperates with CBC to ensure the proper processing of pri-miRNAs.22-24 Interestingly, the accuracy of pri-miRNA processing requires HYL1 dephosphorylation that is triggered by a C-TERMINAL DOMAIN PHOSPHATASE-LIKE 1 (CPL1).27 Recently it has been shown that the efficiency of pri-miRNA recruitment to DCL1-HYL1-SE complex is also improved by a RNA binding protein TOUGH (TGH).28 Other proteins required for proper plant miRNA biogenesis are DDL, STA1, SICLE (SIC), NOT2, and RACK1.29-33 Mutations in the splicing factor STA1 gene have been shown to interfere with both pre-mRNA and pri-miRNA splicing that leads to the accumulation of pri-miRNAs and concurrently to the downregulation of miRNA expression.34 NOT2a and NOT2b proteins were suggested to participate in coupling the RNA Pol II transcriptional complex with the pri-miRNA processing machinery.32 Thus, recent identification of these new components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway suggests that very complex set of processing events leading from miRNA primary transcripts to miRNA/miRNA* duplexes takes place in the nucleus, and that many aspects of pri-miRNA processing still require further studies to identify all players and interactions involved in this process.

Structure of microRNA genes

Mammalian miRNAs are encoded mainly within introns of protein-coding or non-coding genes (80%).35 Unlike those of mammals, the microRNAs of plants are mostly exonic and they are encoded by independent transcriptional units.36 However, some examples of plant miRNAs encoded by protein-coding genes have also been described. Until now, 12 intronic miRNAs have been found in the genome of Arabidopsis thaliana.37,38 Our bioinformatic and experimental studies revealed that 17 more miRNAs of A. thaliana are also encoded within introns of protein- and non-coding genes (manuscript in preparation). Thus, in the A. thaliana genome approximately 8% of miRNAs are encoded within introns of host genes, while the remaining represent independent transcriptional units. The precise structure of most A. thaliana MIR genes is still unknown. Surprisingly, for the miRNA genes representing independent transcriptional units with known structures, it turned out that they are very long (from 378 bp to 4975 bp), and many of them contain multiple introns.17,18,39,40 These introns undergo complex alternative splicing, providing a possible mechanism for the regulation of miRNA processing in A. thaliana.38,41 Our estimations have shown that approximately 50% of A. thaliana miRNA genes contains intron(s). In the majority of intron-containing precursors, the miRNA-enclosing hairpin loop structure is located within the first exon. Why are short miRNAs encoded by such long transcripts, often containing multiple introns? Are introns and/or splicing required for proper miRNA biogenesis? Recent studies revealed that both introns and their splicing are important for the regulation of pri-miRNA processing and that this is mandatory for the accumulation of the proper amount of mature miRNA in the plant cell, as well as for proper regulation of targeted genes.

Introns stimulate plant pri-miRNA processing

The role of introns in pri-miRNA processing has been shown in the case of 3 Arabidopsis MIR genes: MIR161, MIR163, and MIR172a.42,43 All of these genes contain at least one intron located 3′ to the miRNA stem-loop. In the case of transgenic Arabidopsis lines in which MIR163 gene construct without intron has been introduced into the genetic background of the mir163–2 null mutant, the level of mature miR163 was strongly reduced.43 Similar transient expression experiments performed in tobacco leaves for MIR161, MIR163, and MIR172a constructs have shown strong downregulation of mature miRNA levels for all intron-deprived MIR variants. Introduction of unrelated introns derived from protein coding genes or from other MIR genes at the original MIR163 intron site restores the mature miR163 accumulation to the level of wild type plants.42 Thus, the presence of introns, regardless of their origin, sequence, and length plays a stimulatory role in miRNA biogenesis, and points to defined, conserved intronic sequences as crucial elements in this process. Moreover, other experiments performed by Schwab and colleagues demonstrated that introns located upstream of the miRNA hairpin structure did not stimulate miRNA accumulation.42 Thus, the location of intron with respect to the miRNA stem-loop structure seems to be important for boosting the accumulation of miRNAs. This observation implies a possible stimulatory contact of splicing machinery elements with the pri-miRNA processing complex, when located downstream from the miRNA stem-loop.

Functional 5′ splice site is required for proper microRNA biogenesis

Mutation of 5′ and/or 3′ splice sites (ss) in MIR gene variants revealed the essential role of the active 5′ splice site in the process of miRNA biogenesis.43 On the other hand, non-active 3′ splice site exhibited much less effect on the level of mature miRNA. The splice donor site is recognized and bound by a U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle (snRNP), which initiates the formation of active spliceosome. Thus, we thereby postulate that in the case of intron-containing pri-miRNA precursors, the presence of yet undefined interactions between U1 snRNP and the pri-miRNA processing machinery leads to an increase in the efficiency of miRNA biogenesis. Our unpublished data indicate that certain U1 snRNP proteins can interact with SERRATE, one of the main players of miRNA biogenesis in plants. In the case of mammalian intronic miRNAs hosted in protein-coding genes, a feed-forward stimulation mechanism has been proposed that in a mutually cooperative way stimulates both splicing and miRNA biogenesis. Moreover, it has been shown that knockdown of U1 splicing factor reduced the accumulation of intronic miRNAs.44 In mammalian intronic miRNAs, a U1snRNP bound to the 5′ ss is located upstream of the stem-loop structure. This is the reverse situation that is observed in plant miRNA transcripts where an exonic miRNA is followed by an intron. Although intron, splicing, and U1 snRNP seem to play a role in miRNA biogenesis of both mammals and plants, it cannot be ascertained yet if different components of U1 snRNP interact with different miRNA biogenesis proteins in both systems. Schwab et al. as well as Hajheidari et al made an interesting observation that in Arabidopsis dcl1 mutants in which miRNA biogenesis is impaired, the efficiency of splicing of introns located downstream of the miRNA stem-loop is increased.42,45 This provides an additional argument for a close interplay between splicing and miRNA biogenesis. Moreover, this may suggest that U1 snRNP is not involved anymore in the interactions with the miRNA biogenesis machinery that slows down splicing. Interestingly, Schwab and colleagues did not observe such a significant reduction of miRNA levels when the donor splice site of the MIR163 transgene was mutated.42 As discussed in their paper, 2 different explanations are possible: 1) the mutations introduced into the donor splice sites abolished splicing but did not prevent inefficient U1snRNP binding, or 2) the difference between promoters used (CaMV35S vs. the native MIR163 promoter) may exert some effects on co-transcriptional splicing and dicing of the pri-miR163. The second hypothesis is supported by the experiments that we have reported in our recently published paper, in which we used the CaMV35S promoter for all MIR161 splice variants: we do not observe such dramatic effects of donor splice site mutations on the miR163 accumulation.43

Ser/Arg-rich (SR) proteins comprise a conserved family of pre-mRNA splicing factors which function in splice site recognition and the spliceosome assembly, and that are required for constitutive and some aspects of alternative splicing.46,47 At least 2 SR proteins, namely SRZ-21 and SRZ-22, interact with the plant U1 snRNP 70K protein.48 Analyses of the biogenesis of miRNAs derived from intron-containing MIR genes in Arabidopsis null mutants of selected SR genes showed that the levels of mature miR161, miR163, and miR171 were decreased in 3 out of 4 mutants tested (rs31–1, rs2z33–1, and sr34–1).43 We do not yet know whether this is due to a direct effect on interactions between SR proteins, the splicing machinery, and the miRNA biogenesis protein complex, or whether this is due to other indirect effects. However, these observations suggest that, like for pre-mRNAs, the splicing of pri-miRNA might be regulated by SR proteins.43

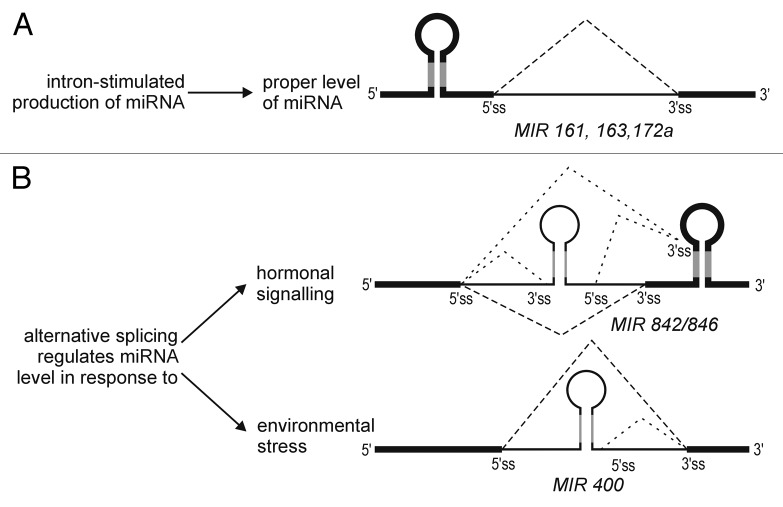

Pri-miRNA polyadenylation site selection depends on the functional 5′ splice site

Studies on plant pri-miRNA structures revealed that multiple polyadenylation sites might co-exist.40,49,50 In the case of Arabidopsis pri-miR163, 2 polyA sites were identified: the proximal site that is located within the intron, and the distal site which is located at the end of the gene.42,43 In the wild type A. thaliana cells, 60% of pri-miR163 is terminated at the distal site.43 The same ratio was observed when the 3′ splice site was inactivated. However, in the mutants in which 5′ ss or both splice sites of MIR163 were mutated, the proximal polyadenylation site was almost exclusively selected.43 Kaida et al. reported that in mammalian cells binding of U1 snRNP protects pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation.51 These results support our observations showing that the functional 5′ ss regulates the accessibility of polyadenylation machinery to pri-miRNA polyA signals. We suggest that the lack of U1 snRNP binding in pri-miR163 favors the proximal, intronic polyA signal recognition, while in the wild type pri-miRNA the distal polyA signal is preferentially selected. It is likely that the spliceosome assembly, aided by specific RNA-binding proteins, may control the length and structure of MIR transcripts and regulate mature miRNA levels depending on tissue and developmental stage. A model of this crosstalk between splicing and dicing machineries is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A model showing splicing machinery stimulatory effect on miRNA biogenesis. A downstream intron and its 5′ splice site play an important role in the miRNA biogenesis boosting effect, while the 3′ splice site plays a minor role in this process. Yet unknown U1 snRNP components interact with the pri-miRNA biogenesis machinery enhancing miRNA production, and inhibiting the proximal (intronic) polyA site selection. SR proteins interacting with U1snRNP complex and other splicing machinery elements exert positive effects on the mature miRNA level. Thick lines represent exons, and thin lines introns. Grey parts of the stem-loop structure mark miRNA and miRNA*. Arrows show stimulatory effects, while a no-headed arrow points to the inhibitory effect. Black arrows depict strong positive effects, while dashed arrows show a weak stimulation. Open boxes inserted within the pri-miRNA structure represent proximal and distal polyadenylation sites (PAS). CBC, Cap-Binding Complex; SE, SERRATE; DCL1, Dicer Like 1; U1 snRNP, U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle; SR, Serine Arginine Rich Proteins; 5′ss and 3′ss means the 5′ and 3′ splicing site, respectively.

The presence of functional splice sites in pri-miR163 are mandatory for pathogen-triggered accumulation of miR163

Ng and colleagues showed that MIR163 is induced by various biotic stresses.52 S-adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent methyltransferase (At1g66690) mRNA is very efficiently sliced by miR163.43,53 In wild type plants, Pseudomonas syringae infection leads to the strong induction of miR163 expression and to a consequent downregulation of At1g66690 target mRNA levels. Our studies revealed that in Arabidopsis mutant plants where both splice sites in pri-miR163 were non-functional (IVS mut), miR163 was not induced and its level remained low.43 Consequently, the level of a miR163 target mRNA (At1g66690) was upregulated. These experiments showed that processing of intron-containing pri-miRNA163 is required for the proper regulation of at least one of miR163 target genes, and in this specific case for proper plant defense response.

Stress- and hormone-induced alternative splicing of intron-containing pri-miRNAs regulate the levels of mature microRNAs in response to environmental cues

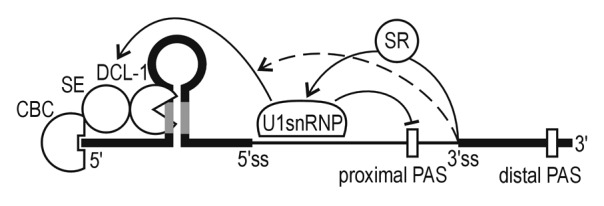

MiRNA response to environmental changes, including responses to biotic and abiotic stresses, has been well-documented.54 Interestingly, recent studies revealed that alternative splicing of pri-miRNAs plays a regulatory role in plant response to hormone signaling. MiR846 and miR842 are encoded within one transcriptional unit but are generated from alternatively spliced isoforms. Both miRNAs are functionally related, and their levels are regulated by abscisic acid (ABA). They are expressed in roots, but upon ABA, the level of miR846 is decreased. This downregulation is accompanied by the decreased level of alternatively spliced isoform from which miR846 can be generated. Thus, ABA regulates alternative splicing, which is crucial for splicing-regulated miRNAs.55 This example illustrates the importance of introns and alternative splicing in the regulation of miRNA level, and fine-tuning of plant response to hormone signaling via pri-miRNA processing.

Another example shows the regulation of miRNA level by alternative splicing induced by heat stress. MiR400 is encoded within an intron of a protein-coding gene. The miR400 level is decreased upon heat stress. High temperature induces alternative splicing that shifts miR400 from intronic to exonic localization. Alternative splicing is accompanied by general increase of the level of mRNA isoform-bearing exonic miR400. Thus, exonic localization of miR400 inhibits its efficient processing from the stress-induced mRNA isoform.38

Alternative splicing of pri-miRNAs has been observed in many cases of intron-containing miRNA genes. The picture that emerges is that introns and alternative splicing have highly relevant roles in regulating the miRNA levels in very specific conditions, and also contribute to proper plant response to stress conditions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Splicing and alternative splicing play a regulatory role in the miRNA production. (A) The presence of an intron downstream to the miRNA stem-loop structure secures the proper miRNA production and plant functioning. (B) Alternative splicing provides a fine-tuning regulatory mechanism that controls the mature miRNA level, enabling plant to respond to various environmental cues. Dashed lines represent splicing and alternative splicing events. Other symbols are as described in

Conclusions

Introns, splicing, and alternative splicing of pri-miRNAs have emerged as important features and mechanisms that affect miRNA biogenesis. Especially the functionality of the 5′ ss seems to influence the efficiency of miRNA processing machinery assembly. In addition, the functional 5′ss appears important for the selection of the polyA site. Thus, both processes, splicing and polyadenylation, influence the proper level of mature miRNAs. These findings are biologically significant since the presence of functional splice sites appears mandatory for pathogen-triggered accumulation of miR163 and proper regulation of at least one of its targets. Moreover, alternative splicing of miRNA-bearing transcripts points to the importance of introns and their splicing regulation in plant response to environmental cues. Our work showed that pri-miRNAs of plants can have extremely complex structures and often contain multiple introns.40 We anticipate that other not-yet-identified features and mechanisms contribute to the tight regulation of miRNA levels in plants.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the Polish National Science Centre: UMO-2011/01/M/NZ2/01345 to Szweykowska-Kulinska Z and UMO-2012/04/M/NZ2/00127 to Jarmolowski A. Vazquez F was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PZP00P3_126329 and PZP00P3_142106).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- miRNA

microRNA

- pri-miRNA

primary transcript of miRNA

- pre-miRNA

miRNA precursor

- snRNP

small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle

- RISC

RNA Induced Silencing Complex

- SR proteins

Ser/Arg-rich (SR) proteins

- DCL1

DICER LIKE 1

- HYL1

HYPONASTIC LEAVES 1

- SE

SERRATE

- CBC

CAP-BINDING COMPLEX

- CBP20

CAP-BINDING PROTEIN 20

- CBP80/ABH1

CAP-BINDING PROTEIN 80/ABSCISIC ACID HYPERSENSITIVE 1

- DDL1

DAWDLE 1

- TGH

TOUGH

- CPL1

C-TERMINAL DOMAIN PHOSPHATASE-LIKE 1

- HST

HASTY

- STA1

STABILIZAD 1

- SIC

SICLE

- NOT2a

known as At-Negative on TATA-less 2

- NOT2b

VIRE2-Interacting Protein2

- RACK1

RECEPTOR for ACTIVATED C KINASE 1

- SRZ-21

RS-containing zinc finger protein 21

- SRZ-22

serine/arginine-rich protein 22

- rs31-1-knockout mutant in the SR protein 31-1 gene

- rs2z33-1

knockout mutant in the RS-containing zinc finger protein 33 gene

- sr34-1

knockout mutant in the Serine/Arginine-Rich Protein Splicing Factor 34 gene

- ABA

Abscisic Acid

- ss

splice site

- bp

base pair

- CaMV 35S

Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voinnet O. Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:669–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vazquez F, Legrand S, Windels D. The biosynthetic pathways and biological scopes of plant small RNAs. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:337–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llave C, Xie Z, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC. Cleavage of Scarecrow-like mRNA targets directed by a class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science. 2002;297:2053–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1076311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang G, Reinhart BJ, Bartel DP, Zamore PD. A biochemical framework for RNA silencing in plants. Genes Dev. 2003;17:49–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodersen P, Sakvarelidze-Achard L, Bruun-Rasmussen M, Dunoyer P, Yamamoto YY, Sieburth L, Voinnet O. Widespread translational inhibition by plant miRNAs and siRNAs. Science. 2008;320:1185–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1159151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–6. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treiber T, Treiber N, Meister G. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and function. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:605–10. doi: 10.1160/TH11-12-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park MY, Wu G, Gonzalez-Sulser A, Vaucheret H, Poethig RS. Nuclear processing and export of microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3691–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405570102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaucheret H, Vazquez F, Crété P, Bartel DP. The action of ARGONAUTE1 in the miRNA pathway and its regulation by the miRNA pathway are crucial for plant development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1187–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.1201404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eamens AL, Smith NA, Curtin SJ, Wang MB, Waterhouse PM. The Arabidopsis thaliana double-stranded RNA binding protein DRB1 directs guide strand selection from microRNA duplexes. RNA. 2009;15:2219–35. doi: 10.1261/rna.1646909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papp I, Mette MF, Aufsatz W, Daxinger L, Schauer SE, Ray A, van der Winden J, Matzke M, Matzke AJM. Evidence for nuclear processing of plant micro RNA and short interfering RNA precursors. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1382–90. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y. Arabidopsis micro-RNA biogenesis through Dicer-like 1 protein functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12753–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403115101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie Z, Allen E, Fahlgren N, Calamar A, Givan SA, Carrington JC. Expression of Arabidopsis MIRNA genes. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2145–54. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kmieciak M, Simpson CG, Lewandowska D, Brown JW, Jarmolowski A. Cloning and characterization of two subunits of Arabidopsis thaliana nuclear cap-binding complex. Gene. 2002;283:171–83. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00859-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugouvieux V, Kwak JM, Schroeder JI. An mRNA cap binding protein, ABH1, modulates early abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2001;106:477–87. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raczynska KD, Simpson CG, Ciesiolka A, Szewc L, Lewandowska D, McNicol J, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z, Brown JW, Jarmolowski A. Involvement of the nuclear cap-binding protein complex in alternative splicing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:265–78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laubinger S, Sachsenberg T, Zeller G, Busch W, Lohmann JU, Rätsch G, Weigel D. Dual roles of the nuclear cap-binding complex and SERRATE in pre-mRNA splicing and microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8795–800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Yang J-Y, Xu J, Jang I-C, Prigge MJ, Chua N-H. Two cap-binding proteins CBP20 and CBP80 are involved in processing primary MicroRNAs. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:1634–44. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L, Liu Z, Lu F, Dong A, Huang H. SERRATE is a novel nuclear regulator in primary microRNA processing in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;47:841–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurihara Y, Takashi Y, Watanabe Y. The interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 is important for efficient and precise processing of pri-miRNA in plant microRNA biogenesis. RNA. 2006;12:206–12. doi: 10.1261/rna.2146906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong Z, Han M-H, Fedoroff N. The RNA-binding proteins HYL1 and SE promote accurate in vitro processing of pri-miRNA by DCL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9970–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803356105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manavella PA, Hagmann J, Ott F, Laubinger S, Franz M, Macek B, Weigel D. Fast-forward genetics identifies plant CPL phosphatases as regulators of miRNA processing factor HYL1. Cell. 2012;151:859–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren G, Xie M, Dou Y, Zhang S, Zhang C, Yu B. Regulation of miRNA abundance by RNA binding protein TOUGH in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12817–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204915109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu B, Bi L, Zheng B, Ji L, Chevalier D, Agarwal M, Ramachandran V, Li W, Lagrange T, Walker JC, et al. The FHA domain proteins DAWDLE in Arabidopsis and SNIP1 in humans act in small RNA biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10073–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804218105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben Chaabane S, Liu R, Chinnusamy V, Kwon Y, Park JH, Kim SY, Zhu JK, Yang SW, Lee BH. STA1, an Arabidopsis pre-mRNA processing factor 6 homolog, is a new player involved in miRNA biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1984–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhan X, Wang B, Li H, Liu R, Kalia RK, Zhu J-K, Chinnusamy V. Arabidopsis proline-rich protein important for development and abiotic stress tolerance is involved in microRNA biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216199109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Song X, Gu L, Li X, Cao S, Chu C, Cui X, Chen X, Cao X. NOT2 proteins promote polymerase II-dependent transcription and interact with multiple MicroRNA biogenesis factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:715–27. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speth C, Willing EM, Rausch S, Schneeberger K, Laubinger S. RACK1 scaffold proteins influence miRNA abundance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;76:433–45. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee BH, Kapoor A, Zhu J, Zhu JK. STABILIZED1, a stress-upregulated nuclear protein, is required for pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA turnover, and stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1736–49. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–39. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel B, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: at the root of plant development? Plant Physiol. 2003;132:709–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown JW, Marshall DF, Echeverria M. Intronic noncoding RNAs and splicing. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan K, Liu P, Wu C-A, Yang G-D, Xu R, Guo Q-H, Huang J-G, Zheng C-C. Stress-induced alternative splicing provides a mechanism for the regulation of microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Cell. 2012;48:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aukerman MJ, Sakai H. Regulation of flowering time and floral organ identity by a MicroRNA and its APETALA2-like target genes. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2730–41. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szarzynska B, Sobkowiak L, Pant BD, Balazadeh S, Scheible WR, Mueller-Roeber B, Jarmolowski A, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z. Gene structures and processing of Arabidopsis thaliana HYL1-dependent pri-miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3083–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobkowiak L, Bielewicz D, Malecka EM, Jakobsen I, Albrechtsen M, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z, Pacak A. The Role of the P1BS Element Containing Promoter-Driven Genes in Pi Transport and Homeostasis in Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:58. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwab R, Speth C, Laubinger S, Voinnet O. Enhanced microRNA accumulation through stemloop-adjacent introns. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:615–21. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bielewicz D, Kalak M, Kalyna M, Windels D, Barta A, Vazquez F, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z, Jarmolowski A. Introns of plant pri-miRNAs enhance miRNA biogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:622–8. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janas MM, Khaled M, Schubert S, Bernstein JG, Golan D, Veguilla RA, Fisher DE, Shomron N, Levy C, Novina CD. Feed-forward microprocessing and splicing activities at a microRNA-containing intron. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hajheidari M, Farrona S, Huettel B, Koncz Z, Koncz C. CDKF;1 and CDKD Protein Kinases Regulate Phosphorylation of Serine Residues in the C-Terminal Domain of Arabidopsis RNA Polymerase II. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1626–42. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096834;PMID:2254778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopato S, Mayeda A, Krainer AR, Barta A. Pre-mRNA splicing in plants: characterization of Ser/Arg splicing factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3074–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy AS. Plant serine/arginine-rich proteins and their role in pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golovkin M, Reddy AS. The plant U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle 70K protein interacts with two novel serine/arginine-rich proteins. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1637–48. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song L, Han M-H, Lesicka J, Fedoroff N. Arabidopsis primary microRNA processing proteins HYL1 and DCL1 define a nuclear body distinct from the Cajal body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruszka K, Pacak A, Swida-Barteczka A, Stefaniak AK, Kaja E, Sierocka I, Karlowski W, Jarmolowski A, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z. Developmentally regulated expression and complex processing of barley pri-microRNAs. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaida D, Berg MG, Younis I, Kasim M, Singh LN, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. U1 snRNP protects pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation. Nature. 2010;468:664–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng DW-K, Zhang C, Miller M, Palmer G, Whiteley M, Tholl D, Chen ZJ. cis- and trans-Regulation of miR163 and target genes confers natural variation of secondary metabolites in two Arabidopsis species and their allopolyploids. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1729–40. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Sung G-H, Spatafora JW, Carrington JC. Evolution of microRNA genes by inverted duplication of target gene sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1282–90. doi: 10.1038/ng1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kruszka K, Pieczynski M, Windels D, Bielewicz D, Jarmolowski A, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z, Vazquez F. Role of microRNAs and other sRNAs of plants in their changing environments. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169:1664–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jia F, Rock CD. MIR846 and MIR842 comprise a cistronic MIRNA pair that is regulated by abscisic acid by alternative splicing in roots of Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;81:447–60. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]