Abstract

The Fe(II) and α-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylase FrbJ was previously demonstrated to utilize FR-900098 synthesizing a second phosphonate FR-33289. Here we assessed its ability to hydroxylate other possible substrates, generating a library of potential antimalarial compounds. Through a series of bioassays and in vitro experiments, we identified two new antimalarials.

The gene frbJ was identified during the cloning and sequencing of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the phosphonate antibiotic FR-900098 from Streptomyces rubellomurinus.1 The enzyme is homologous to Fe(II) and α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent hydroxylases, which catalyze substrate hydroxylation with concomitant oxidative decomposition of αKG to succinate and carbon dioxide.2 Enzymes within this family play a pivotal role in a diverse set of reactions, including antibiotic synthesis where they generate pathway precursors, intermediates, and final products.3–4 For example, clavaminate synthase (CAS) catalyzes three independent oxidative reactions in the biosynthesis of clavulanic acid.5 Interestingly, another enzyme from this family has demonstrated epoxidase activity in the semisynthetic pathway for the phosphonate antibiotic fosfomycin. The enzyme encoded by epoA from Penicillium decumbens converts the substrate cis-propenylphosphonic acid to the final product fosfomycin.6 Although the natural function of this enzyme in the native host is unknown, the epoxidase activity signifies the broad range of functions of Fe(II) and αKG-dependent enzymes.

Deletion studies of frbJ within the heterologous hosts Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli indicated that the enzyme was not required for FR-900098 biosynthesis, leading to some uncertainty as to its function.1, 7 It was originally postulated that FrbJ might be responsible for the N-hydroxylation step; however, catalysis of this nature by this class of enzyme would have been exceedingly rare. Fe(II) and αKG-dependent enzymes can efficiently catalyze the hydroxylation of inactivated C-H bonds, so we investigated whether FrbJ might be involved in the synthesis of another phosphonate antibiotic FR-33289 ((R)-2-hydroxy-3-(N-acetyl-N-hydroxyamino)propylphosphonic acid).8–9 Production of this compound was observed in both the native producer S. rubellomurinus producer strain and a heterologous S. lividans 4G7 host. We have recently shown that FrbJ is indeed capable of catalyzing the hydroxylation of FR-900098 at the β-position (Fig. 1).7 This study focused on the expression, purification, and further biochemical characterization of FrbJ and the determination of its role in FR-900098 biosynthesis. We also demonstrated its ability to catalyze the hydroxylation of additional substrates as part of the creation of a new library of potential antimalarial drugs, all of which were screened for inhibitory activity against a malarial drug target.

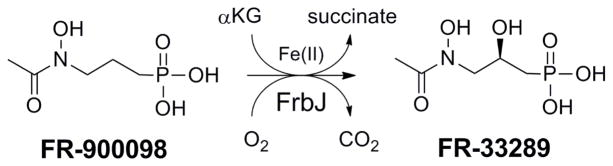

Fig. 1.

FrbJ catalyzes the hydroxylation of FR-900098 to FR-33289 with concomitant oxidative decomposition of αKG to succinate and carbon dioxide.

The full-length frbJ gene was cloned from fosmid 4G7.7 E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with this construct and IPTG-induced cultures were purified to homogeneity. As previously described, the final steps in the pathway contain a series of intermediates conjugated to the nucleotide cytidine-5′-monophosphate (CMP).7 If hydroxylation by FrbJ were to occur before cleavage of the CMP by FrbI, CMP-5′-FR-900098 could serve as the true substrate for the enzyme. FrbJ showed activity towards the natural substrate FR-900098 but not the nucleotide containing substrate, indicating that nucleotide cleavage must occur before hydroxylation in the biosynthetic pathway (Table 1). We also checked for enzymatic activity with another known phosphonate antibiotic, fosmidomycin (FR-31564). This substrate contains an N-formyl group instead of the N-acetyl group on FR-900098. FrbJ demonstrated activity towards this structurally similar substrate, but displayed a 6-fold preference for the natural substrate. As a result of fosmidomycin hydroxylation by FrbJ, a novel phosphonate was able to be synthesized, (R)-2-hydroxy-3-(N-formyl-N-hydroxyamino)propylphosphonic acid, hereby called hydroxyfosmidomycin. To the best of our knowledge, this compound has never been detected from a biological source or produced synthetically.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of FrbJ.

| Substrate | kcat (min−1) (mean ± SD) | KM (μM) (mean ± SD) | kcat/KM (mM−1 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FR-900098 | 147 ± 31 | 289 ± 48 | 509 |

| Fosmidomycin | 57.3 ± 8.1 | 700 ± 137 | 81.9 |

| CMP-5′-FR-900098 | NR |

NR: no reaction detected; SD: standard deviation

Heterologous production of FR-33289 in E. coli was attempted by expressing all of the genes in the biosynthetic cluster, excluding frbI (pETDuet-frbABCD, pRSFDuet-frbHFG, pACYCDuet-frbEJ-dxrB). Although FR-900098 production was evident in the LC-MS analysis, no detectable amounts of FR-33289 were detected. Cell-free lysate of E. coli strains that only expressed FrbJ was incubated with FR-900098. The lysate only demonstrated conversion to FR-33289 upon addition of exogenous α-ketoglutarate, suggesting that FrbJ may be regulated by the intracellular concentration of this cofactor, thus preventing in vivo production in E. coli.

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites can be effectively regulated via the availability of precursors, cofactors, and cellular energy originating from primary metabolism. Rate-limiting enzymes control the flux of these critical metabolites to ensure that secondary metabolism does not become favored over primary metabolism. Khetan et al. described the function of lysine-6-aminotransferase (LAT), which was determined to be the rate-limiting enzyme in cephamycin biosynthesis from Streptomyces clavuligerus.10 This enzyme, which utilizes αKG as a cofactor in the conversion of lysine to α-aminoadipic acid, is the first step in the biosynthetic pathway. The authors measured the KM for αKG to be 8.6 mM, substantially higher than its intracellular concentration ranging from 0.3–1.3 mM.10 The KM value for LAT is also higher than that of other characterized Fe(II) and αKG-dependent hydroxylases, which is typically on the order of 10s of micromolar.11–13 In the same way that LAT regulates the cephamycin biosynthetic pathway, FrbJ may regulate the ratio of the two phosphonates FR-900098 and FR-33289 using α-ketoglutarate. The KM of αKG for the oxidation of FR-900098 by FrbJ was determined to be 1.3 ± 0.19 mM, comparable to the high KM of LAT and close to the value of the intracellular level of αKG. One crucial difference between the two pathways is that the entire cephamycin biosynthesis can be regulated by the intracellular concentration of αKG since LAT is the first enzyme in the pathway, making the high KM of the enzyme ideal for switching the biosynthesis of cephamycin entirely on or off.The lower KM of FrbJ is a much weaker control valve, which can regulate the conversion of FR-900098 to FR-33289.

The dianionic charge of phosphonates at physiological pH poses problems for their efficacy; in particular, they suffer from poor bioavailability as a result of their high polarity. The oral bioavailability of FR-900098 and fosmidomycin is moderate with a resorption rate of approximately 30%.14 Recent efforts have focused on masking the charged moiety of the phosphonate group through esterification. Such chemically synthesized prodrugs cross the gastrointestinal tract into the blood stream with higher efficiency, where they are cleaved by broad specificity plasma esterases, thus releasing the free and active phosphonate.15–17 We sought a method for the preparation of similar esterified FR-900098 prodrugs through biosynthetic means. The gene cluster for dehydrophos from Streptomyces luridus contains an S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent O-methyltransferase encoded by dhpI.18 DhpI has very low substrate specificity,19 and is able to O-methylate the phosphonate of a wide range of substrates, making it an excellent candidate for further engineering.

As shown in Table 1, FrbJ is capable of catalyzing the hydroxylation of FR-900098 and fosmidomycin to produce FR-33289 and hydroxyfosmidomycin, respectively. These four phosphonates were used as the basis for the creation of a prospective antimalarial library; each was methylated by DhpI (Fig. 2). FR-900098 and fosmidomycin were commercially available and the subsequent six compounds were synthesized by in vitro reactions with purified FrbJ, DhpI, and Pfs. The phosphonate library was then purified to remove any unreacted substrate or cofactors. Although not identical to the di-ester prodrugs prepared by chemical synthesis, these methylated compounds may enhance the bioavailability of the final active phosphonate drugs.

Fig. 2.

Prospective antimalarial library created using FrbJ and DhpI (with Pfs). Due to the low substrate specificity of DhpI, hydroxylation by FrbJ was carried out before O-methylation.

The library was first screened by bioassays of an E. coli phosphonate uptake strain.1 Bioassay plates of this FR-900098-sensitive strain showed clear inhibition zones around discs impregnated with FR-900098, FR-33289, fosmidomycin, and hydroxyfosmidomycin; all of which were lost with a resistant E. coli strain. However, there was no detectable growth inhibition for any of the corresponding methylated compounds with the FR-900098-sensitive strain. To ensure the lack of bioactivity on the plate was not specific for the Dxr target, we utilized a second phosphonate antibiotic with a completely different target. Fosfomycin, a broad-range antibacterial used to treat urinary tract infections,20 and the corresponding fosfomycin-OMe was prepared in a similar method as described for the other phosphonates. Similar to the prospective methylated antimalarials, there was no growth inhibition of the sensitive E. coli strain by fosfomycin-OMe. The methyl group is either not cleaved in these in vivo bioassays, preventing the release of the active phosphonate, or the methyl ester hampers uptake.

The library was also assessed using purified Plasmodium falciparum Dxr (pfDxr). The recombinant enzyme was codon-optimized for heterologous expression in E. coli and was designed to lack the N-terminal signal peptide.21–22 Enzymatic activity was monitored by NADPH oxidation at 340 nm, and subsequent inhibition values for the IC50 and KI were obtained for each of the prospective antimalarial compounds. Similar to the in vivo bioassays, only the free, unmethylated phosphonate compounds demonstrated in vitro inhibition of pfDxr. There was no apparent decrease in the enzymatic activity upon addition of the methylated compounds to any of the reaction mixtures. The approximately two-fold difference between the inhibition of FR-900098 and fosmidomycin is similar to published data21. Also, the inhibition constants for FR-900098 and fosmidomycin with their hydroxylated counterparts, FR-33289 and hydroxyfosmidomycin, respectively, were determined to be nearly identical to each other (Table 2). Even though the natural pfDxr substrate also contains a secondary hydroxyl group similar to FR-33289 and hydroxyfosmidomycin, albeit at different positions on the carbon backbone, there was no apparent increase in inhibition compared to FR-900098 and fosmidomycin.

Table 2.

Inhibition of purified Dxr from Plasmodium falciparum by members of the phosphonate library.

| Substrate | IC50 (nM) (mean ± SD) | KI (nM) (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| FR-900098 | 15 ± 3 | 3.2 ± 1.0 |

| FR-33289 | 16 ± 3 | 3.0 ± 0.8 |

| Fosmidomycin | 36 ± 6 | 6.8 ± 1.6 |

| Hydroxyfosmidomycin | 41 ± 5 | 7.1 ± 1.4 |

| FR-900098-OMe | NI | NI |

| FR-33289-OMe | NI | NI |

| Fosmidomycin-OMe | NI | NI |

| Hydroxyfosmidomycin-OMe | NI | NI |

NI: no enzyme inhibition detected; SD: standard deviation

The combinatorial biosynthesis with FrbJ was successful in producing two new antimalarial target compounds, FR-33289 and hydroxyfosmidomycin. The E. coli bioassays showed some improvement for these hydroxylated compounds as the zones of inhibition were slightly larger. Although the inhibition of the Dxr enzyme itself does not change, the bioavailability of these hydroxylated compounds appears to increase. In order to more accurately assess these compounds, we will look to expand the scope of the inhibition assays to include Plasmodium species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences GM077596 (H.Z. and W.A.V). M.A.D. acknowledges support from the US National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Award 5 T32 GM070421 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [Materials and Experimental Procedures]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Eliot AC, Griffin BM, Thomas PM, Johannes TW, Kelleher NL, Zhao H, Metcalf WW. Chem Biol. 2008;15:765–770. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausinger RP. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:21–68. doi: 10.1080/10409230490440541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:186–193. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schofield CJ, Zhang Z. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:722–731. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd MD, Merritt KD, Lee V, Sewell TJ, Wha-Son B, Baldwin JE, Schofield CJ, Elson SW, Baggaley KH, Nicholson NH. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:10201–10220. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe M, Sumida N, Murakami S, Anzai H, Thompson CJ, Tateno Y, Murakami T. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1036–1044. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1036-1044.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johannes TW, DeSieno MA, Griffin BM, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL, Metcalf WW, Zhao H. Chem Biol. 2010;17:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuhara M, Kuroda Y, Goto T, Okamoto M, Terano H, Kohsaka M, Aoki H, Imanaka H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980;33:24–28. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuroda Y, Okuhara M, Goto T, Okamoto M, Terano H, Kohsaka M, Aoki H, Imanaka H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1980;33:29–35. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khetan A, Malmberg LH, Kyung YS, Sherman DH, Hu WS. Biotechnol Prog. 1999;15:1020–1027. doi: 10.1021/bp990090f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White AK, Metcalf WW. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38262–38271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg JR, Kertesz MA, Leisinger T. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23031–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaz FM, Ofman R, Westinga K, Back JW, Wanders RJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33512–33517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchiya T, Ishibashi K, Terakawa M, Nishiyama M, Itoh N, Noguchi H. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1982;7:59–64. doi: 10.1007/BF03189544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichenberg A, Wiesner J, Weidemeyer C, Dreiseidler E, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Beck E, Schlitzer M, Jomaa H. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:833–835. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortmann R, Wiesner J, Reichenberg A, Henschker D, Beck E, Jomaa H, Schlitzer M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2163–2166. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiesner J, Ortmann R, Jomaa H, Schlitzer M. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2007;340:667–669. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200700069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Circello BT, Eliot AC, Lee JH, van der Donk WA, Metcalf WW. Chem Biol. 2010;17:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Bae B, Kuemin M, Circello BT, Metcalf WW, Nair SK, van der Donk WA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17557–17562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006848107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendlin D, Stapley EO, Jackson M, Wallick H, Miller AK, Wolf FJ, Miller TW, Chaiet L, Kahan FM, Foltz EL, Woodruff HB, Mata JM, Hernandez S, Mochales S. Science. 1969;166:122–123. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3901.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Weidemeyer C, Hintz M, Turbachova I, Eberl M, Zeidler J, Lichtenthaler HK, Soldati D, Beck E. Science. 1999;285:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae B, Cobb RE, Li Z, DeSieno MA, Zhao H, Nair SK. submitted. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.