Abstract

The formation, maintenance, and reorganization of synapses are critical for brain development and the responses of neuronal circuits to environmental challenges. Here we describe a novel role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator (PGC-1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, in the formation and maintenance of dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons. In cultured hippocampal neurons, PGC-1α overexpression increases dendritic spines and enhances the molecular differentiation of synapses, whereas knockdown of PGC-1α inhibits spinogenesis and synaptogenesis.. PGC-1α knockdown also reduces the density of dendritic spines in hippocampal dentate granule neurons in vivo. We further show that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) stimulates PGC-1α-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis by activating ERKs and CREB. PGC-1α knockdown inhibits BDNF to promote dendritic spine formation without affecting expression and activation of the BDNF receptor TrkB. Our findings suggest that PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis play important roles in the formation and maintenance of hippocampal dendritic spines and synapses.

Keywords: mitochondria, biogenesis, BDNF, PGC-1α, dendritic spines, hippocampus, synaptogenesis, CREB, TFAM

Introduction

Mitochondrial biogenesis, the growth and division of pre-existing mitochondria, is a process requiring the spatiotemporally coordinated synthesis of proteins encoded by the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes1. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma co-activator (PGC-1α) has been identified as a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis2,3,4. Transcription factors that guide PGC-1α action to specific genes include nuclear receptors and nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), which controls the expression of mitochondrial proteins including cytochrome-c (cyt-c), and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) which is critical for the initiation of mtDNA transcription and replication3,5. PGC1α is expressed at high levels in mitochondria-rich cells with high energy demands including cardiac myocytes, skeletal-muscle cells and neurons6. PGC-1α expression is increased in response to signals that relay metabolic needs, such as exposure to cold, fasting and physical exercise1,5,7. An increase of PGC-1α levels is sufficient to engage cellular pathways important for energy metabolism including mitochondrial biogenesis and adaptive thermogenesis2,5,7.

During CNS development, neurons are generated from proliferative neural stem cells in the process of neurogenesis. The newly generated neurons then grow axons and dendrites and form synapses to establish functional neuronal circuits. Beyond providing ATP, the evidence that mitochondria play regulatory roles in sculpting cytoarchitecture during development of nervous systems is based largely on correlational data such as changes in the location or properties of mitochondria during developmental processes8. A previous study suggested a role for mitochondrial dynamics in dendritic spine plasticity9. However, whether mitochondrial biogenesis plays roles in the formation and plasticity of synapses in the developing and/or adult brain is unknown. During neuronal differentiation and maturation the number of mitochondria per cell increases, and treatment with chloramphenicol (an inhibitor of mitochondrial protein synthesis) prevents differentiation of the cells whereas oligomycin (an inhibitor of the mitochondrial ATP production) does not, suggesting that increased mitochondrial mass is required for neuronal differentiation10. Because the energy demand of neurons increases as they become excitable and form synapses, we designed experiments to determine whether PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis regulate the formation and plasticity of neural circuits.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays key roles in the development, maintenance and repair of the nervous system11, and has emerged as an important regulator of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory12, 13. BDNF has rapid effects on synaptic transmission and membrane excitability by increasing the number of docked vesicles at the active zones of synapses14 and/or altering the activation kinetics of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors15. BDNF also regulates slower cellular events involved in the formation and adaptive modification of neuronal circuits. For example, BDNF increases dendritic complexity in hippocampal dentate granule neurons16 and increases the number of dendritic spines in CA1 pyramidal neurons14,17. BDNF and its high-affinity receptor TrkB are widely expressed in the developing and adult mammalian brain 18 It was previously reported that BDNF can influence cellular energy metabolism in embryonic CNS neurons19, but it is not known if BDNF signaling affects PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis, nor whether such actions of BDNF are critical for the formation and plasticity of synapses in the developing and adult brain.

Here we used molecular manipulations of PGC-1α levels to establish requirements for PGC-1α in the regulation of dendrite outgrowth and dendritic spine formation in embryonic hippocampal neurons, and in the maintenance of hippocampal dendritic spines in the adult brain. Moreover, we show that BDNF enhances dendritic spine formation, in part, by a mechanism involving upregulation of PGC-1α by the transcription factor cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB).

Results

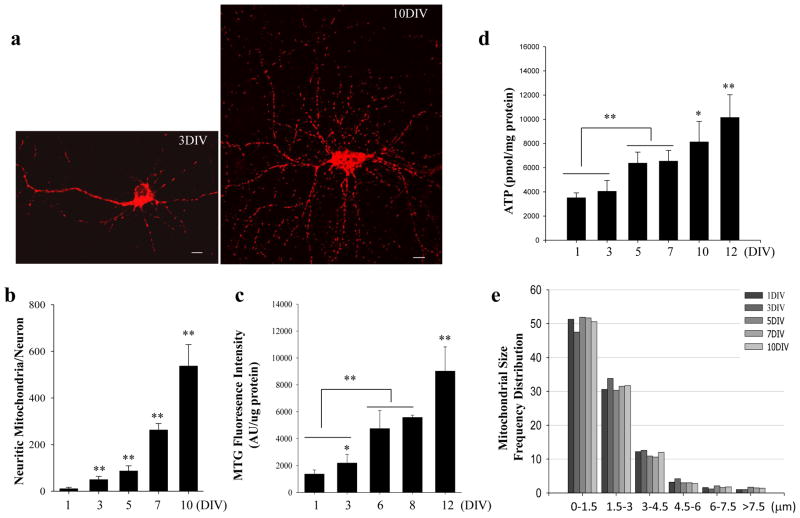

Mitochondrial biogenesis occurs in association with neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis

When dissociated cells from E17 rat hippocampus are cultured in neuronal differentiation medium, they differentiate into neurons; subsequently, the newborn neurons grow an axon and dendrites and eventually form synapses20. Mitochondria in individual neurons were visualized by loading them with Mitotracker Green (mt-green) at 1 day in culture or by transfecting them with a mt-DsRed construct21 (DsRed fused to the mitochondrial targeting sequence of cytochrome c oxidase). Due to low transfection efficiency (~5%), the mitochondria in the neurites of individual transfected neurons are clearly visualized (Fig. 1a). The mitochondrial number in the neurons progressively increased as axons and dendrites grew and synapses formed (Fig. 1a, b). We also analyzed the total mitochondrial mass of the neurons using Mitotracker Green (MTG) fluorescence intensity in living neurons. MTG fluorescence intensity increased by ~8-fold between culture days 1 and 12 (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, cellular ATP levels (normalized to cellular protein level) increased progressively during the 12 day period in culture (Fig. 1d). The fold increase in mitochondrial mass was greater than the fold increase in ATP levels, which is likely due to the increased ATP utilization that occurs in neurons as they become electrically excitable and spontaneous synaptic activity occurs. The mitochondrial length frequency distribution did not change significantly, with an average mitochondrial length of approximately 2 μm being maintained through culture day 10 (Fig. 1e). Therefore, the increased mitochondrial mass as neurons grow results primarily from increased biogenesis of mitochondria which are distributed throughout the neurites. These findings reveal an association between mitochondrial biogenesis and the active period of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis, suggesting a potential role for mitochondria in these developmental processes.

Figure 1. Numbers of mitochondria increases during the differentiation and maturation of hippocampal neurons.

(a) Confocal images of primary cultured hippocampal neurons at 3 and 10 days (3 DIV and 10 DIV) in culture showing mt-Dsred fluorescence in individual neurons. Scale bars = 10 μm. (b) Results of counts of mitochondrial number in individual neurons at different culture days, as indicated. (c) Results of measurements of mitochondrial mass determined by mitotracker-green fluorescence intensity normalized to cellular protein concentration (see Methods). (d) Results of measurements of ATP concentration (normalized to cellular protein levels) at different culture days as indicated. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4–5 separate cultures). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 (ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls post-hoc tests). (e) The length of mitochondria in neurites was measured and the frequencies of the mitochondrial size were plotted (10–20 neurons were analyzed for each condition).

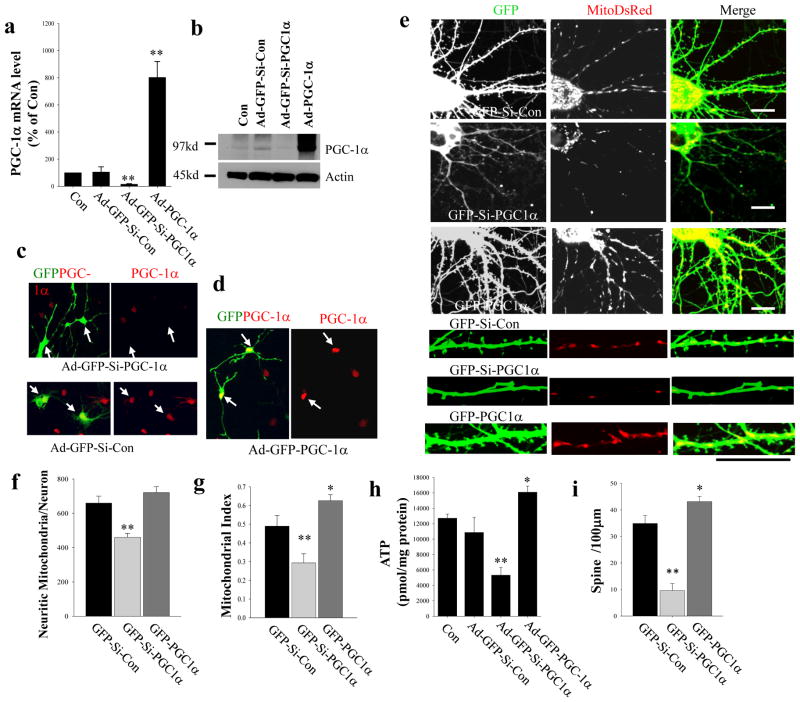

PGC-1α enhances dendritic spine formation and maintenance

To investigate whether mitochondria are involved in regulating neural plasticity during neuronal maturation, we used molecular genetic methods to target PGC-1α, a key regulator of genes that control mitochondria biogenesis1,2,3,4,5. We employed RNA interference technology to reduce PGC-1α levels in cultured hippocampal neurons. The efficacy of siRNA in reducing the level of PGC-1α, or oϕ PGC-1α overexpression, were established by analyzing PGC-1α mRNA or protein levels after infecting neurons with adenoviral constructs that express GFP and shRNA with a scrambled sequence (Ad-GFP-Si-Con), GFP and shRNA directed against the PGC-1α mRNA (Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α), or GFP and PGC-1α (Ad-GFP-PGC-1α) (Fig. 2a–d). Neurons were co-transfected with a mt-DsRed construct in combination with constructs that express GFP-Si-Con or GFP-Si-PGC-1α or GFP-PGC-1α on culture day 5, and confocal image analysis of the neurons was performed on culture day 12 to determine the effects of PGC-1α deficiency or over-expression on mitochondria and synapses. There was a marked reduction in the number and density of mitochondria in the dendrites of neurons expressing GFP-Si-PGC-1α compared to those expressing GFP-Si-Con while, in contrast, neurons overexpressing PGC-1α (GFP-PGC-1α) exhibited a significant increase in mitochondrial density in dendrites compared to control neurons (Fig. 2e). Quantitative analysis of mitochondria number in neurites revealed a ~30% reduction in GFP-Si-PGC-1α neurons (460.6 ± 22.9; n = 15) compared to GFP-Si-Con cells (659.6 ± 40.2; n = 15; p<0.001, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 2f). Since the average mitochondrial size is smaller in GFP-Si-PGC-1α neurons (1.2 ± 0.025 μm; n = 15) compared to GFP-Si-Con cells (1.92 ± 0.037 μm; n = 15), we also quantified the dendritic mitochondrial index (mitochondrial length/dendritic length) which revealed a ~40% reduction in GFP-Si-PGC-1α neurons (0.29 ± 0.049; n = 15) compared to GFP-Si-Con cells (0.49 ± 0.057; n = 15, p<0.001, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 2g).

Figure 2. siRNA-mediated knockdown of PGC-1α reduces mitochondrial content and dendritic spine formation in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(a) Quantitative PCR using specific primers to PGC-1α demonstrates a large reduction of PGC-1α mRNA in Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α infected cells and increased PGC-1α mRNA levels in Ad-GFP-PGC1α infected cells (48 h infections) compared to uninfected neurons and neurons expressing a scrambled shRNA (Ad-GFP-Si-Con). (b) Immunoblot analysis showing that levels of PGC-1α (~95 kd) are elevated in neurons infected with Ad-GFP-PGC1α and are reduced in neurons infected with Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α compared to uninfected neurons and neurons infected with Ad-GFP-Si-Con. (c, d) Hippocampal neurons at 5 days in culture were transfected with constructs of GFP-Si- PGC-1α, GFP-Si-Con or GFP-PGC-1α, for 48 h and then fixed for immunostaining using an antibody againt PGC-1α (red). (c) GFP+ cells (arrows) in GFP-Si-PGC-1α transfected neurons exhibit little or no PGC-1α fluorescence compared to the surrounding GFP− cells or to GFP-Si-Con transfected neurons. (d) GFP+ cells (arrows) in GFP- PGC-1α transfected neurons exhibit a stronger PGC-1α fluorescence intensity, with the PGC-1α concentrated in the nucleus, compared to surrounding GFP− cells. (e) Representative confocal images of mito-DsRed and GFP in the dendritic arbors of 12 day-old hippocampal neurons that were co-transfected with mito-DsRed and either GFP-Si-con, GFP-Si-PGC-1α or GFP-PGC-1α constructs on culture day 5. The lower panels show higher magnification of dendrites. Bars = 20 μm. (f, g) Results of counts of mitochondrial numbers in the neurites of individual neurons (e) and dendritic mitochondrial density index (mitochondria/neurite length) (g) (in hippocampal neurons that were co-transfected with mitoDsRed and either GFP-Si-con or GFP-Si-PGC-1α (n = 10–15 neurons analyzed for each condition). Values are the mean ± SD. **p<0.01 compared to the corresponding GFP-Si-Con value (Student’s t-test).. (h) Results of measurements of ATP levels in 12 day-old hippocampal neurons that were infected with Ad-GFP-Si-con, Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α or Ad-GFP-PGC-1α on culture day 5. The results are normalized to protein concentration. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4–5 separate cultures). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (i) Spine density (number of spines per 100 μm) were quantified in hippocampal neurons that were transfected with either GFP-Si-con or GFP-Si-PGC-1α. n = 10–15 neurons analyzed for each condition. Values are the mean ± SD. **p<0.01 compared to the corresponding GFP-Si-Con value (Student’s t-test).

Because importation of mt-Dsred 21 into mitochondria is a membrane potential-dependent process, we immunostained the neurons expressing mt-Dsred with an antibody against porin (a protein located in the outer membrane of all mitochondria). The results show that all porin-immunoreactive mitochondria are also mt-Dsred positive regardless of whether PCC-1α levels are knocked down (Fig. S1a, b). In addition, immunoblot analysis of porin demonstrated a significant (~40%) reduction of porin levels in neurons in which PGC-1α was knocked down compared to neurons expressing a scrambled control shRNA (Fig. S1c, d). These data collectively confirm a mitochondrial mass reduction in neurons in response to PGC-1α knockdown. There was no apparent increase of mitochondrial number in neurons overexpressing PGC-1α; however, the average mitochondrial length was increased significantly in GFP-PGC-1α neurons (2.63 ± 0.041 μm; n = 15) compared to GFP-Si-Con cells (1.92 ± 0.037 μm; n = 15; p<0.01, Student’s t-test), and the dendritic mitochondrial index was ~28% greater in GFP-PGC-1α neurons (0.62 ± 0.036; n = 15) compared to GFP-Si-Con cells (0.49 ± 0.057; n = 15; p<0.001, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 2f, g), indicating an increase in mitochondrial mass.

Next, we found that neurons in which PGC-1α was knocked down had significantly reduced ATP levels, whereas neurons overexpressing PGC-1α had elevated ATP levels, compared to control neurons (Fig. 2h). There was a ~55% reduction of ATP levels in Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α infected neurons (5328.1 ± 998.4 pmole/mg protein) and a ~20% increase of ATP levels in PGC-1α overexpressing neurons (16088.3 ± 783.0 pmol/mg protein) compared to uninfected neurons (12711.8 ± 532.4 pmol/mg protein) and neurons infected with Ad- GFP-Si-Con (10868.9 ± 1952.3 pmol/mg protein). Collectively, these data indicate that mitochondrial mass and ATP levels in hippocampal neurons are dependent upon PGC-1α.

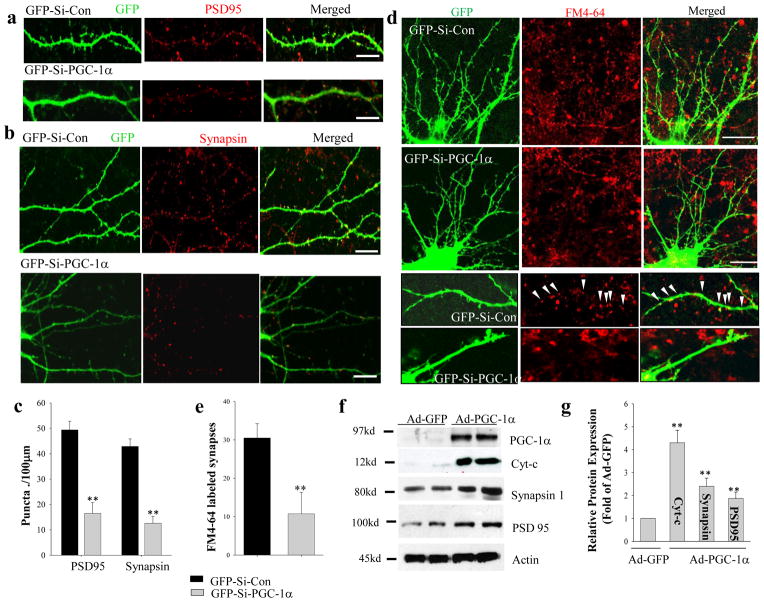

Examination of GFP fluorescence in dendrites revealed a marked reduction by ~75% in the density of dendritic spines in neurons expressing GFP-Si-PGC-1α (9.6 ± 2.6 spines/100 μm) and a significant increase by ~20% in neurons expressing GFP-PGC-1α (43.1 ± 1.9) compared to neurons expressing GFP-Si-Con (34.9 ± 3.0 spines/100 μm; n = 12) (Fig. 2e, i). Immunostaining demonstrated that immunoreactive puncta for Synapsin, a protein associated with small synaptic vesicles in presynaptic terminals22 and PSD95, a prominent postsynaptic density scaffold protein23, were also markedly reduced by 67% and 71%, respectively in neurons expressing GFP-Si-PGC-1α compared to those expressing GFP-Si-Con (PSD95, 16.5 ± 4.3 versus 49.4 ± 3.4 puncta/100 μm; Synapsin I, 12.6 ± 2.7 versus 42.9 ± 3.0 puncta/100 μm; n = 10) (Fig. 3a–c).

Figure 3. Evidence that PGC-1α plays a pivotal role in the molecular differentiation of synapses in developing hippocampal neurons.

(a, b) Representative confocal images of dendritic segments at high magnification in 12 day-old neurons fixed and immunostained with PSD95 (a) or synapsin I (b) antibodies after transfecting GFP-Si-con or GFP-Si-PGC1α constructs on culture day 5. Bars = 20 μm. (c) numbers of PSD95 and Synapsin I immunoreactive puncta (number of puncta per 100 μm) (n = 10–15 neurons analyzed for each condition). Values are the mean ± SD. **p<0.001 compared to the corresponding GFP-Si-Con value(Student’s t-test). (d) Images of hippocampal neurons at 12 days in culture that had been transfected with GFP-Si-con or GFP-Si-PGC1α on culture day 5. Neurons were then processed for evaluation of activity-dependent uptake of the fluorescent probe FM4-64FX into presynaptic terminals (see Methods). (e) FM4-64FX-labeled puncta (red) were quantified (number of FM4-64 puncta per 100 μm) in 10–15 neurons/culture/condition. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4–5 separate cultures). **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (f) A representative immunoblot of PGC-1α, Cyt-c, Synapsin 1, PSD95 and actin in 12 day-old hippocampal neurons that were infected with Ad-GFP or Ad-GFP-PGC-1α on culture day 5. (g) Results of densitometric analysis of blots showing Cyt-c, Synapsin 1 and PSD95 protein levels (fold change compared to the value for neurons infected with Ad-GFP-Con) as in (f). Values are mean ± SD (n = 4–5 separate cultures). **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Double immunostaining 12 DIV hippocampal neurons using antibodies against synapsin and PSD95, revealed that ~ 80% puncta are immunoreactive with both antibodies indicating that these puncta represent synapses (Fig. S2). This observation indicates that the dramatic suppression (~75%) of dendritic spine density in neurons in which PGC-1α is knocked down reflects a reduction in synapse formation. Indeed, a similar result was obtained when functional synapses were identified by KCl-stimulated uptake of the dye FM4-64 into presynaptic terminals24, 25. Seven days after transfecting 5 DIV neurons with GFP-Si-Con or GFP-Si-PGC-1α constructs, neurons were assayed for FM4-64 uptake during a 5 minute period of exposure to KCl (Fig. 3d). Knockdown of PGC-1α caused a significant decrease in the number of synapses labeled with FM4-64 compared to neurons expressing the scrambled control shRNA (Fig. 3d, e).

There was a significant reduction of the dendritic arbor quantified by measuring the overall dendritic length (by ~20%) and the dendritic complexity quantified by counting the number of dendrite bifurcations (by ~30%) in GFP-Si-PGC-1α neurons compared to GFP-Si-Con neurons (Fig. S3). We further evaluated dendritic spine density in neurons at 15 DIV after knockdown of PGC-1α at 5 DIV. The control neurons exhibited an increase of dendritic spine density compared to DIV 12 neurons, whereas neurons in which PGC-1α was knocked down did not exhibit a greater spine density on DIV 15 compared to DIV 12. These results indicate that significant suppression of PGC-1α expression inhibits, but does not delay dendritic spine formation. Moreover, previous studies26–28 using PGC-1α null mice have demonstrated that loss of PGC-1α leads to neurodegeneration. We evaluated cell death in neurons transfected with constructs or infected with adenovirus to express either PGC-1α shRNA or scrambled shRNA and observed neither increased bright and condensed apoptotic nuclei in cells stained with Hoechst 33342 (Fig. S4d), nor increased activated caspase-3 immunofluorescence or increased cleaved form of caspase-3 by immunoblot analysis in neurons expressing PGC-1α shRNA (Fig. S4a–c). Therefore, the significant suppression of dendtritic spines and functional synapses after reducing PGC-1α levels is not due to neurodegeneration.

We further determined whether synaptogenesis might be augmented by increasing PGC-1α levels. Neurons were infected on culture day 5 with an adenoviral vector that expresses GFP alone (Ad-GFP) or a vector that expresses GFP plus PGC-1α (Ad-GFP-PGC-1α; the efficacy of this vector in elevating PGC-1α levels was established as shown in Figure 2a, b and d. On culture day 12 the neurons were collected for biochemical analyses to evaluate synaptogenesis. Compared to neurons infected with Ad-GFP, those infected with Ad-PGC-1α exhibited significant increases in levels of PGC-1α and the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c, as well as elevated levels of Synapsin I and PSD95 (Fig. 3d, e). Thus, elevation of PGC-1α levels is sufficient to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis and molecular differentiation of synapses in hippocampal neurons.

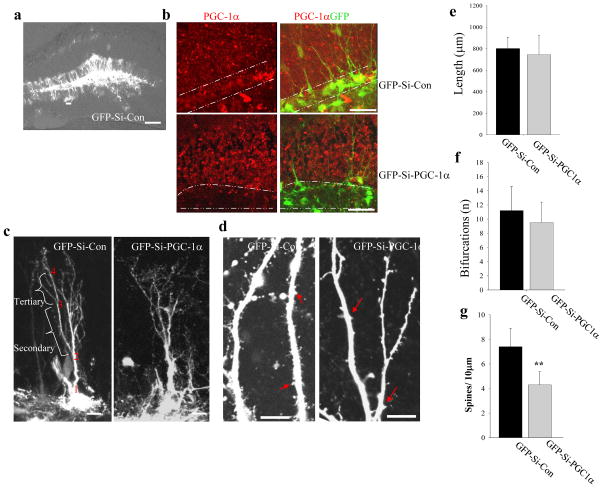

We next asked whether PGC-1α plays a role in the maintenance of synapses in the adult brain. Adenoviruses (Ad-GFP-Si-PGC1α or Ad-GFP-Si-Con) were delivered into the hippocampal dentate gyrus of 2 month-old mice via stereotaxic microinjection. Two weeks later, coronal brain sections were prepared and GFP fluorescence was imaged revealing GFP expression in many dentate granule neurons in which the fluorescence was distributed throughout the dendritic arbors (Fig. 4a). The immunostaining intensity of PGC-1α in Ad-GFP-Si- PGC-1α infected cells was much fainter than that in Ad-GFP-Si-Con infected cells, confirming the efficacy of PGC-1α knockdown in vivo (Fig. 4b). For quantitative analysis, the apical dendritic arbors and segments from secondary and tertiary dendrites (Fig. 4c, d) were imaged using 25x water or 63x oil immersion objectives on a Zeiss confocal microscope. In contrast to the effects of PGC1α knockdown in cultured hippocampal neurons, there was no significant effect of PGC1α depletion on total apical dendrite length or the complexity of the dendritic arbor measured by counting the number of bifurcations (Ad-GFP-Si-Con versus Ad-GFP-Si-PGC1α; length, 802 ± 104.3 versus 745 ± 179 μm; bifurcations 11.2 ± 3.4 versus 9.5 ± 2.9; 15–20 neurons analyzed) (Fig. 4e, f). However, the granule neurons expressing Ad-GFP-Si-PGC1α exhibited a significant reduction in dendritic spine density of ~40% (4.3 ± 1.1 spines/10 μm compared to 7.4 ± 1.5 spines/10 μm in Ad-GFP-Si-Con neurons; 15–20 neurons analyzed, p<0.001, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 4g). The results indicate that transient depletion of PGC-1α in adult mature hippocampal neurons reduces the density of dentritic spines without altering the existing dendritic morphology. PGC-1α therefore plays pivotal roles in synapse maintenance in the hippocampus in vivo.

Figure 4. PGC-1α is required for the maintenance of dendritic spines in adult mouse hippocampal dentate gyrus granule neurons.

(a) Low magnification images showing GFP fluorescence in neurons in the dentate gyrus. Adenoviruses that contain GFP-Si-Con or GFP-Si-PGC1α were injected into the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of 2 month-old male mice. Two weeks later the mice were euthanized, and brains were sectioned and confocal images of GFP fluorescence were acquired. (b) Representative confocal images showing PGC-1α immunostaining (red) and GFP (green) in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of mice in which granule neurons were infected with either Ad-GFP-Si-Con or Ad-GFP-Si-PGC1α. (c, d) Representative confocal images showing dendritic trees (c) and dendritic spines (d) of neurons infected with either GFP-Si-Con or GFP-Si-PGC1α. The dendritic spines were quantified in the secondary and tertiary segment of dendrites which are illustrated in b (bracelets). Scale bars in (a)=100 μm, (b) = 50 μm and in (c, d) =10 μm. (e–g) Results of quantitative analysis of total dendritic length, number of bifurcations, and dendritic spine density in dentate granule neurons infected with either Ad-GFP-Si-Con or Ad-GFP-Si-PGC1α. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5 mice; 15–20 neurons analyzed per condition. **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

BDNF enhances PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial biogenesis

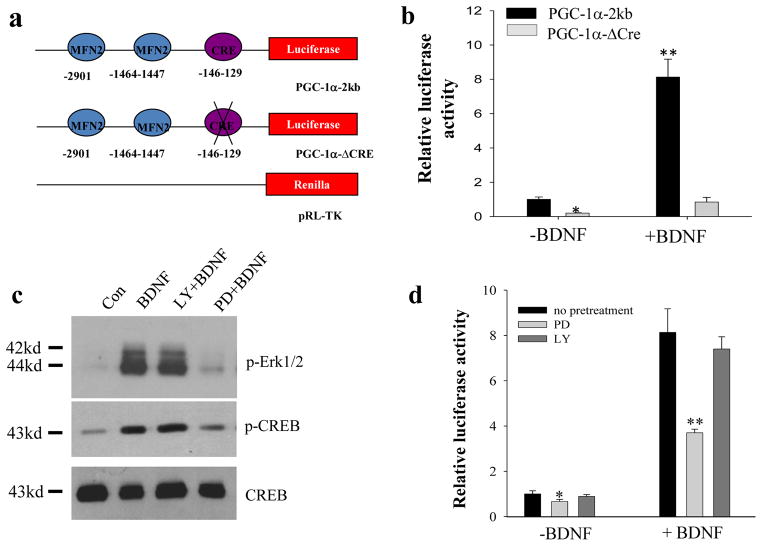

It has been established that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) promotes neuronal differentiation and survival11, enhances dendrite growth, spine formation and synaptogenesis, and facilitates synaptic plasticity16,17. We next asked whether PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis were involved in BDNF-induced synaptogenesis. In cultured hippocampal neurons, treatment with BDNF from culture days 5 to 12 resulted in a significant increase in the expression of PSD95 and Synapsin I in a BDNF concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S5). Strikingly, we found that the activation of the Pgc-1α promoter was increased approximately 8-fold in the presence of BDNF (Fig. 5b) in hippocampal neurons transfected with a Pgc-1α promoter-driven luciferase reporter plasmid. In contrast, the Pgc-1α promoter with a deletion in the CRE site (CREB binding site) exhibited reduced basal activation and was unresponsive to BDNF treatment (Fig. 5a, b).

Figure 5. BDNF stimulates PGC-1α promoter activity via activation of MAP kinases and CREB.

(a) Illustration of the structure of the 2 kb PGC-1α promoter linked to a firefly luciferase reporter gene harboring no mutations (PGC-1α-2kb) or a CRE site deletion (PGC1α-ΔCRE), and the Renilla luciferase-expressing plasmid (pRL-TK) used as an internal control. (b) Relative luciferase activity of PGC-1α-2kb and PGC-1α-ΔCRE in neurons treated with or without BDNF for 32 h. Dual luciferase activity was measured at 48 h of transfection and the firefly luciferase activity was normalized to the level of pRL-TK Renilla luciferase activity and plotted as the fold of control (PGC1α-2kb, no BDNF treatment). Values are mean ± SD. *p<0.05 and **p<0.001 (n=5) (ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls post-hoc tests). (c) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and CREB in control and BDNF-treated neurons. Neurons were pretreated with vehicle or kinase inhibitors 30 min prior to exposure to BDNF (40 ng/ml) for 30 min: MAPK inhibitor, PD980059 (PD, 20 μM); PI3K inhibitor LY 290043 (LY, 20 μM). p-Erk1/2 and p-CREB are bands in blots probed with antibodies that selectively recognize phospho-Erk1/2 and phospho-CREB; the same blots were re-probed with an antibody against total CREB (phosphorylation-independent antibody). (d) Relative luciferase activity of PGC1α-2kb in cells incubated under the indicated conditions. The analysis and plot are same as that described in panel b. Values are mean ± SD, *p<0.05 and **p<0.001 (n=5) (ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls post-hoc tests).

Activation of the high-affinity BDNF receptor TrkB results in phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor and subsequent recruitment and activation of signaling proteins that engage extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt kinase pathway29. We found that PD98059, an inhibitor of MEK (a kinase that phosphorylates ERKs), significantly attenuated BDNF-induced Pgc-1α promoter activity, whereas the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY98003 did not (Fig. 5d). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that the phosphorylation of CREB in response to BDNF was attenuated by PD98059, but was unaffected by the PI3 kinase inhibitors LY290043 and wortmannin (Fig. 5c; Fig. S6). These data indicate that both ERKs and CREB mediate BDNF–induced PGC-1α promoter activity. Indeed, BDNF treatment resulted in a significant elevation of PGC-1α mRNA and protein levels within 24 h (Fig. 6a, b). Transcription factors that guide PGC-1α action to specific genes include nuclear receptors and nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), which controls the expression of mitochondrial proteins including cytochrome-c (cyt-c), and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) which is critical for the initiation of mitochondrial DNA transcription and replication3,5. Levels of TFAM and NRF1 mRNA and protein were elevated in response to BDNF, with Nrf1 mRNA levels increasing within 4 h of stimulation with BDNF (Fig. 6a, b).

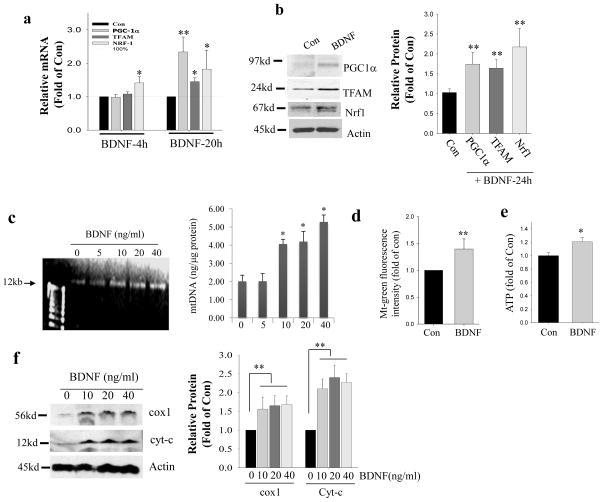

Figure 6. BDNF enhances PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis.

(a, b) Effects of BDNF on PGC-1α, NRF1 and TFAM mRNA and protein levels in cultured hippocampal neurons. Cultured hippocampal neurons (7 days in culture) were treated with 40 ng/ml BDNF for the indicated time periods. mRNA (by quantitative PCR) and protein levels (densitometry analysis) are expressed as fold change compared to the value for vehicle-treated control neurons. Values are mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.001 (n=4) (Student’s t-test). (c) A representative gel showing mtDNA (left) and results of measurement of the amount of mtDNA normalized to protein concentration in cultured hippocampal neurons after treating with BDNF at indicated concentrations, or vehicle control, for 7 days (from culture days 5 – 12). *p<0.05 compared to the 0 ng/ml BDNF value (ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls post-hoc tests). (d) Mitochondrial mass determined by mt-green fluorescence intensity normalized to cellular protein concentration (see Methods). (e) Results of measurements of ATP concentrations in hippocampal neurons after 7 days of treatment with BDNF or vehicle; values were normalized to protein concentration. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3 separate cultures). *p<0.05 (Student’s t-test). (f) A representative immunoblot of the mitochondrial proteins Cox1 and Cyt-c, and actin, in neurons that had been treated for 7 days with the indicated concentrations of BDNF. The graph shows the results of densitometric analysis of the blots (n = 3 separate cultures). For graphs in panels d, e and f: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

To determine whether BDNF enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, we treated hippocampal neurons with BDNF or vehicle daily for 7 days beginning on culture day 5, and then measured the amount of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in the neurons. The mtDNA content of the neurons was significantly increased by approximately 2-fold in neurons treated with 10–40 ng/ml BDNF (Fig. 6c). The BDNF-treated (20 ng/ml) neurons exhibited a significant increase (by ~50%) in mitochondrial mass indicated by a greater amount of Mitotracker Green fluorescence in BDNF-treated neurons and ATP production (by ~20%) compared to control neurons (Fig. 6d, e). In addition, levels of two mitochondrial proteins, cytochrome oxidase 1 (cox1) and cytochrome c (cyt-c) were also elevated considerably in response to BDNF (Fig. 6f).

PGC-1α mediates BDNF-induced synaptogenesis

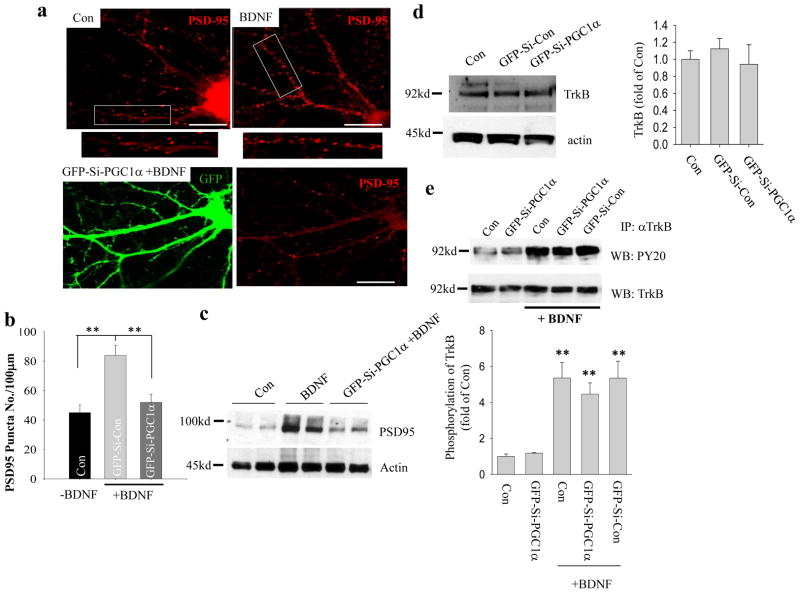

The findings described above indicated that BDNF signaling significantly increases mitochondrial biogenesis and up-regulates PGC-1α expression, and that PGC-1α is important for the development and/or maintenance of dendritic spines and synapses. We next asked whether PGC-1α and PGC-1α–dependent mitochondrial biogenesis mediate BDNF-induced synapse formation. Hippocampal neurons treated with BDNF from culture day 5 until culture day 12 exhibited a significant increase in PSD95-immunoreactive dendritic puncta (84 ± 6.7 puncta/100 μm dendritic segment; 15–30 neurons analyzed, p<0.001, Student’s t-test) compared to control neurons (45 ± 5.3 puncta/100 μm), whereas the suppression of PGC-1α expression by Ad-si-PGC-1α impaired the ability of BDNF to promote synaptogenesis as indicated by significantly reduced numbers of PSD95-immunoreactive dendritic puncta (52 ± 5.6 puncta/100 μm dendritic segment; 15–30 neurons analyzed, p<0.001 compared to BDNF treated neurons, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 7a, b), and abolished the ability of BDNF to increase PSD95 protein levels as determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, immunoblot analysis showed that the level of BDNF high affinity receptor TrkB was unchanged in hippocampal neurons with PGC-1α knockdown (Fig. 7d)., Moreover, immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that phosphorylation of TrkB stimulated by BDNF is unchanged in PGC-1α knockdown neurons compared with either control neurons or Ad-GFP-Si-Con infected neurons (Fig. 7e). Thus, suppression of PGC-1α expression does not affect TrkB levels or its activation by BDNF in hippocampal neurons. These results provide evidence that PGC-1α and PGC-1α–mediated mitochondrial biogenesis serves as a downstream signaling component in the enhancement of synaptogenesis by BDNF.

Figure 7. PGC-1α knockdown inhibits BDNF-induced synaptogenesis without affecting TrkB expression or activation.

(a) Confocal images showing PSD95 immunostaining in cultured hippocampal neurons (12 days in culture) that had been treated with vehicle (Con) or BDNF (40 ng/ml) (BDNF) or transfected with GFP-Si-PGC1α on culture day 5 and then treated with 40 ng/ml BDNF (GFP-Si-PGC-1α + BDNF). Scale bars = 20 μm. (b) Results of quantitative analysis of PSD95 immunoreactive puncta in dendrites of neurons from the indicated treatment groups. Bars represent the mean ± SD (n =5 cultures with 15–30 neurons analyzed per condition). **p<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (c) Immunoblot analysis of PSD95 protein levels in neurons from the indicated treatment groups. (d) Immunoblot analysis of TrkB in hippocampal neurons 7 days after infection with Ad-GFP-Si-con or Ad-GFP-Si-PGC1α, compared to uninfected neurons. (e) Immunoprecipitation and quantitative analysis of TrkB physophorylation. TrkB in protein extracts (0.5 mg) from cultured hippocampal neurons in the indicated treatment groups was immunoprecipitated using a rabbit anti-TrkB antibody, and then subjected to immunoblot analysis using the anti phopho-tyrosine antibody PY20 (Cell Signaling). **p<0.01 (n = 3) (Student’s t-test).

Discussion

Our findings reveal previously unknown roles for PGC-1α in the formation and maintenance of synapses in developing hippocampal neurons, and in the maintenance of synapses in the adult hippocampus. BDNF, which plays critical roles in neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the developing and adult hippocampus12,13,30, significantly enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis as indicated by increases in mitochondrial mass and up-regulation of PGC-1α promoter activity and transcription and expression of PGC-1α, NRF-1 and the mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM. Moreover, we found that ERKs and CREB are required for BDNF-induced up-regulation of PGC-1α.

Mitochondria, as the major energy source in cells, are essential for the excitability and survival of neurons8. The formation of hippocampal synapses is associated with increased expression and activation of ligand-gated ion channels and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, which increases the energy demand required to operate the ion-motive ATPases that restore the membrane potential31. Mitochondrial biogenesis increases the energy production capability of cells32 which may be required for neurons to form and maintain functional synapses. In the present study, we selectively modulated mitochondrial biogenesis using molecular genetic methods that target PGC-1α and provided direct evidence that this key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis also plays an important role in the formation of dendritic spines as well as functional synapses. Knock-down of PGC-1α expression, which reduced the amount of mitochondria in dendrites, resulted in decreased density of dendritic spines and synapses. Conversly, overexpression of PGC-1α, which increased mitochondrial biogenesis, also increased levels of synaptic proteins (Synapsin 1 and PSD95). Consistent with a previous report that neurite outgrowth is reduced in cultured striatal neurons from PGC-1α null mice26, we found that reduction of PGC-1α levels resulted in a moderate reduction in the complexity of dendritic arbors in embryonic hippocampal neurons. However, knockdown of PGC-1α did not affect dendrite length in adult dentate granule neurons, but did reduce dendritic spine density. These findings suggest that PGC-1α plays roles in regulating the dendritic morphology and synaptic connectivity of neuronal circuits in the developing brain, and in the maintenance of synapses in the adult hippocampus.

Mitochondrial biogenesis is regulated by several signaling pathways and transcription factors33. PGC-1α has been shown previously to induce mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism in muscle cells, adipocytes and cardiac myocytes2,3,4. The latter studies also provided evidence that the transcription factor Nrf1/2 mediates the effects of PGC-1α on the expression of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins including the mitochondrial transcription factor (TFAM), which is essential for the initiation of mitochondrial DNA transcription and replication2,34. We found that BDNF significantly enhances PGC-1α, Nrf1 and TFAM expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in cultured hippocampal neurons. A functional CRE site in the PGC-1α co-activator gene, which is activated by BDNF-induced activation of ERKs and CREB, mediates PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial biogenesis. Consistent with our findings, previous studies also indicated that CREB activation enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in non-neural cells34, 35. In addition to ERKs, several other kinases regulate CREB activity in neurons including cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcium/camodulin-dependent kinase36,37. It is therefore likely that signals that elevate cyclic AMP and Ca2+ levels will also increase PGC-1α expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in neurons.

Binding of BDNF to TrkB results in phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor38. Thus activated, TrkB signals via Ras and downstream kinases including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and Akt kinase39–42. We found that PGC-1α knockdown did not affect levels of trkB nor its ability to be activated by BDNF, but did significantly reduce the ability of BDNF to increase dendritic spine density. The latter findings suggest PGC-1α plays a critical role in mediating the enhancement of synapse formation in response to BDNF. Interestingly, we found that BDNF up-regulates PGC-1α in hippocampal neurons by a mechanism involving ERKs and CREB, but not Akt. Previous studies have shown that the PI3 kinase -Akt pathway43, ERKs44–46 and the transcription f actor CREB47 play pivotal roles in synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Our findings therefore suggest BDNF regulates synapse formation and plasticity by multiple mechanisms, one of which is critically dependent upon PGC-1α.

Previous studies have shown that several signaling mechanisms that regulate neurite outgrowth also regulate synaptogenesis, with glutamate and BDNF signaling being prominent examples48. We found that knockdown of PGC-1α attenuates the ability of BDNF to enhance dendritic spine and synapse formation in embryonic hippocampal neurons. It is therefore likely that PGC-1α plays important roles in enabling synaptogenesis as well as neurite outgrowth. Interestingly, as with BDNF, other signaling molecules such as nitric oxide34, 49 and estrogen50 that stimulate PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells also regulate neural plasticity51, 52. In addition, previous studies have shown that exercise and caloric restriction stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells by a PGC-1α-mediated mechanism2,3, and both exercise and dietary restriction increase BDNF expression53, 54 in hippocampus and preserve synaptic function in animal models of Huntington’s55, Parkinson’s56 and Alzheimer’s diseases57. Thus, our findings suggest roles for PGC-1α and mitochondrial biogenesis in the protection and plasticity of neuronal circuits throughout life.

Reduced levels of PGC-1α have recently been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders that involve synaptic degeneration. Studies of animal models and human subjects suggest that in Huntington’s disease (HD) mutant huntingtin results in decreased production of cortical BDNF and leads to insufficient neurotrophic support for striatal neurons, which then die58. It was recently shown that mutant huntingtin also represses PGC-1α gene transcription by associating with the promoter and interfering with the CREB/TAF4-dependent transcriptional pathway critical for the regulation of PGC-1α gene expression27. In addition, selective elimination of PGC-1α in neurons of adult mice results in degeneration of striatal neurons28, suggesting that PGC-1α expression may limit the ability of vulnerable neurons to adequately respond to energy demands in HD. Impaired mitochondrial function and deficits in BDNF signaling are also implicated in Alzheimer’s disease59, 60, Parkinson’s disease55, 61 and ischemic stroke62. It will therefore be of considerable interest to determine whether PGC1α can be targeted for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders.

METHODS

Hippocampal cell cultures and experimental treatments

Cultures of hippocampal neurons were prepared from embryonic day 17 Sprague-Dawley rats. Dissociated cells were seeded into polyethyleneimine-coated plastic dishes or glass coverslips in MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS at a density of 30,000 cells/cm2. After cells attached to the substrate (3 h) the medium was replaced with Neurobasal medium containing B27 supplements (Invitrogen). BDNF was from Invitrogen and PD98059, LY290043 and wortmannin were from Cell Signaling Technology.

Immunocytochemistry

For immunofluorescence cytochemistry, fixed cells were preincubated with blocking solution (0.2% Triton X-100, 10% normal goat serum) in PBS for 30 min, and then incubated overnight with a primary antibody followed with appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were counterstained with propidium iodide (PI) or DAPI for 10 min. The primary antibodies and their dilutions were: rabbit anti PGC1α (1:100, Santa Cruz), anti synapsin (1:200, Cell Signaling), mouse anti PSD95 (1:200, Thermo Scientific). The secondary antibody was rhodamine- conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:500, Molecular Probes).

Immunoblot analysis and immunoprecipitation

Tissues or cells were solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and the protein concentration in each sample was determined using a protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard. 30 μg proteins were resolved on 4–10% SDS polyacrylamide gels and electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Following standard methods to incubate the membrane with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies, the reaction product in the membrane was visualized using an ECL Western blot detection kit. The primary antibodies included those that selectively recognize PGC1α (rabbit, 1:100, Santa Cruz), synapsin 1 (rabbit, 1:1000, Cell Signaling), synaptophysin (mouse, 1:500, Sigma), Cox1 (mouse, 1:500, Molecular Probes), cytochrome C (mouse, 1:1000, BD Parmingen), TFAM (rabbit, 1:500, Abcam), NRF1 (rabbit, 1:500, Life Span Bioscience) and, p-CREB, CREB p-AKT, p-ERKs and ERKS (rabbit, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), PSD95 (mouse, 1:500, Thermo Scientific), actin (mouse, 1:2000, Sigma).

For immunoprecipitation analysis, neurons were solubilized in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 1.0% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, and 5 mM EDTA) with proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Equal amounts of protein extracts (0.5 mg) were precleared by incubating with 50 μl of protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz) for 1 h at 4°C on a rotating shaker and were then centrifuged to precipitate the beads. Supernatant was collected, incubated with 5 μg of antibodies against TrkB (Santa Cruz, rabbit polyclonal) overnight at 4°C in a shaker. The samples were then mixed with 100 μl of protein A/G agarose and incubated for 2 h. Pellet protein A/G beads by centrifugation were repeatedly washed four times with 1 ml of lysis buffer, the final pellets were eluted in protein loading buffer, and samples were vortexed and boiled for 3 min. Beads were precipitated by centrifugation, and supernatants were collected for immunoblot analysis using an anti phospho-tyrosine antibody PY20 (Cell Sigaling)..

Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR amplification

Total RNAs were isolated using RNAeasy purification kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNAs were synthesized using 1 μg total RNA in a 20 μl reaction with Superscript II and oligo(dT)12–18 (Invitrogen). For real time PCR, the primers and TaqMan® probes (for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), PGC1α, Nrf1, and TFAM) and TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix were purchased from Applied Biosystems. 2 μl of 20-fold diluted reverse-transcription mixture (cDNA) was used as initial template for real-time PCR. The real-time PCR reactions for each RNA sample were performed in triplicate. The default setting of the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System was used for the PCR reaction. The GAPDH level was used as the internal control for all other genes.

Adenovirus packaging, infections and plasmid transfections

Adeno-PGC1α virus was the generous gift from Dr. Pere Puigserver (Johns Hopkins University). Ad-PGC1α SiRNA (GFP-Si-PGC-1α) and Ad-PGC1α Si-Con (GFP-Si-Con) plasmids, both of which also contain GFP cDNA, were a generous gift from Dr. Marc Montminy (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies). The sequence of the PGC RNAi was GGTGGATTGAAGTGGTGTAGA (mouse PGC1α 150–170bp) and the sequence for the unspecific RNAi control was GGCATTACAGTATCGATCAGA. Adeno-PGC1α virus was amplified by directly infecting HEK293 cells at 70–80% confluence (Invitrogen). Ad-PGC1α SiRNA and Ad-PGC1α SiCon plasmids were digested with Pac 1, and then were transfected into HEK293 cells to produce adenovirus. Infected or transfected cells were harvested and pelleted by centrifugation and high-titer stocks of recombinant adenoviruses were purified by Adeno-X virus purification kit (Clonetech). The cultured neurons were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 50 pfu/cell. To co-transfect mt-DsRed and GFP-Si-PGC-1α or GFP-Si-Con, plasmid DNAs (2μg each) were mixed and transfected using calcium phosphate in cultured hippocampal neurons.

Mitochondrial mass measurements and analysis of mtDNA

For mitochondrial mass measurements, cultured hippocampal neurons were loaded with Mitotracker Green at final concentration of 500 nM and incubated for 20 min. Equal amounts from each sample lysis were analyzed in a Bio Assay Reader (excitation and emission are 485 nm and 535 nm respectively, Perkin Elmer) to quantify fluorescence intensity. The values were normalized by protein concentrations. For analysis of mtDNA, mtDNA was isolated from cultured neurons using a Mitochondrial DNA Isolation Kit (Biovison). Briefly, neurons were washed with ice-cold PBS, then scraped and collected in 1 ml cyotsol extraction buffer. After homogenization using a Dounce homogenizer, the homogenates were separated into cytosol (supernatant) and mitochondrial fractions (pellet) by differential centrifugation. The mitochondrial pellets were lysed and incubated in 50°C in 30 μl of mitochondrial lysis buffer containing protein degradation enzymes. mtDNA was isolated by ethanol precipitation. A small aliqout of homogenates was reserved for protein quantification and mtDNA content were normalized to the protein concentration.

Luciferase Assay of PGC1α promoter activity

The 2kb PGC-1α promoter-luciferase construct (PGC-1α-2kb) and PGC-1α promoter dCRE-luciferase construct (with a site-directed mutagenesis to remove the CREB binding site) (PGC-1α-ΔCRE) have been described previously63. Both constructs were purchased from Addgene. Primary cultured neurons were co-transfected with 2 μg pRL-TK Vector (Promega) expressing Renilla luciferase and 2 μg PGC-1α-2kb or PGC-1α-ΔCRE using Fugene 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were incubated in the presence of experimental treatments for 32 h, and luciferase activity was quantified using a Dual-Luciferase-Reporter System (Promega). Luciferase activity in each sample was normalized to the internal control renilla luciferase activity (4–6 cultures per condition were analyzed).

In vivo studies

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and mounted on a stereotaxic apparatus. A sagittal incision was made through the skin along the midline of the head, and a hole was drilled on the skull at the position of 2.18 mm posterior and 1.6 mm lateral (right) to bregma. The tip of injector was lowered into the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (1.6 mm below the surface of the brain). One microliter of solution, containing either Ad-Si-PGC-1α or Ad-GFP-Si-Con (5 mice received Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α and 5 mice received Ad-GFP-Si-Con), was injected slowly using a microinjection pump over 3 min. Two weeks after injection, brains were perfusion fixed and processed for immunohistology. Coronal sections containing the dentate gyrus (30 μm thickness) were collected and GFP fluorescence was imaged with a confocal microscope (Zeiss inverted LSM510).

FM4-64 labeling

Primary hippocampal neurons which had been transfected with GFP-Si-Con or GFP-Si-PGC-1α were rinsed with HBSS medium and then incubated 3 minutes with 5 μM FM4-64FX (Invitrogen) and 100 mM KCl. The cultures were then incubated for 10 minutes in the presence of the dye without 100 mM KCl to allow for complete endocytosis of all released vesicles. Neurons were then washed with fresh HBSS to remove extracellular FM4-64FX, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes and images of intracellular FM4-64FX fluorescence were acquired using a confocal microscope.

Imaging and image analysis

For cultured neurons, images were acquired using a Zeiss inverted LSM510 confocal microscope with 63x (NA, 1.4) or 25x (NA, 0.8) and 10x (NA, 0.3) objectives. The length of dendrites and mitochondria were traced and measured with the aid of LSM510 software. All the spines and dendrites in one image frame were measured. The vast majority of PSD-95 or synapsin I puncta were counted along GFP illustrated dendrites in GFP-Si-PGC-1α or GFP-Si-Con transfected neurons. Mitochondrial number in neurites and the dendritic mitochondrial index (total mitochondrial length/dendritic length) were analyzed in neurons co-transfected with GFP-Si-PGC-1α or GFP-Si-Con and mt-DsRed. For in vivo analysis of dendritic spine density, segments from secondary and tertiary dendrites on 5 neurons per mouse were sampled from dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus. Dendritic segments were viewed through a 63X oil immersion objective on a Zeiss confocal microscope. These images were imported into Reconstruct for determination of the 3-D length of the segment and spine counting. For analysis of dendritic length and bifurcations, cells were scanned using a 25X objective throughout the apical dendritic arbors. Images stacks were imported into reconstruct for 3D tracing.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between control and treatment groups were performed by using Student’s unpaired t test or ANOVA when appropriate. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Aging. We thank Dr. Heping Cheng (Peking University, China) for his critical reading and inputs. We thank Dr. Marc Montminy (Salk Institute for Biological Studies) for the Ad-GFP-Si-PGC-1α and Ad-GFP-Si-Con) plasmids and Dr. Pere Puigserver (John Hopkins University) for Ad-GFP-PGC-1α adenovirus.

Footnotes

Author contributions: A. C. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and prepared an initial draft of the manuscript; R. W. performed data analysis; J-L. Y., N. K. and T. G. S. performed cell culture experiments; X. O. and Y. L. performed biochemical analyses; M. P. M. directed the research project, contributed to the study design, provided animals and supplies, and polished the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. Mitochondrial-nuclear communications. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:701–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052305.091720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:78–90. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehman JJ, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:847–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knutti D, Kralli A. PGC-1, a versatile coactivator. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:360–365. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson U, Scarpulla RC. Pgc-1-related coactivator, a novel, serum-inducible coactivator of nuclear respiratory factor 1-dependent transcription in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3738–3749. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3738-3749.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puigserver P, et al. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattson MP, Gleichmann M, Cheng A. Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron. 2008;60:748–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Okamoto K, Hayashi Y, Sheng M. The importance of dendritic mitochondria in the morphogenesis and plasticity of spines and synapses. Cell. 2004;119:873–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vayssière JL, et al. Participation of the mitochondrial genome in the differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1992;28A:763–772. doi: 10.1007/BF02631065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin GR, Barde YA. Physiology of the neurotrophins. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:289–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunha C, Brambilla R, Thomas KL. Simple role for BDNF in learning and memory? Front Mol Neurosci. 2010;3:1–14. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.001.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T. Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8856–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyler WJ, Pozzo-Miller LD. BDNF enhances quantal neurotransmitter release and increases the number of docked vesicles at the active zones of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4249–4258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04249.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Keifer J. BDNF-induced synaptic delivery of AMPAR subunits is differentially dependent on NMDA receptors and requires ERK. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolwani RJ, et al. BDNF overexpression increases dendrite complexity in hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2002;114:795–805. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso M, Medina JH, Pozzo-Miller L. ERK1/2 activation is necessary for BDNF to increase dendritic spine density in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Learn Mem. 2004;11:172–178. doi: 10.1101/lm.67804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:71–124. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burkhalter J, Fiumelli H, Allaman I, Chatton JY, Martin JL. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor stimulates energy metabolism in developing cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8212–8220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-23-08212.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng A, et al. Telomere protection mechanisms change during neurogenesis and neuronal maturation: newly generated neurons are hypersensitive to telomere and DNA damage. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3722–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0590-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizzuto R, Brini M, Pizzo P, Murgia M, Pozzan T. Chimeric green fluorescent protein as a tool for visualizing subcellular organelles in living cells. Curr Biol. 1995;5:635–642. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Camilli P, Harris SM, Jr, Huttner WB, Greengard P. Synapsin I (Protein I), a nerve terminal-specific phosphoprotein. II. Its specific association with synaptic vesicles demonstrated by immunocytochemistry in agarose-embedded synaptosomes. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1355–1373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.5.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scannevin RH, Huganir RL. Postsynaptic organization and regulation of excitatory synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:133–141. doi: 10.1038/35039075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaffield MA, Betz WJ. Imaging synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis with FM dyes. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2916–21. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pyle JL, Kavalali ET, Choi S, Tsien RW. Visualization of synaptic activity in hippocampal slices with FM1-43 enabled by fluorescence quenching. Neuron. 1999;24:803–8. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J, et al. Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell. 2004;119:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui L, et al. Transcriptional repression of PGC-1alpha by mutant huntingtin leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Cell. 2006;127:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma D, Li S, Lucas EK, Cowell RM, Lin JD. Neuronal inactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) protects mice from diet-induced obesity and leads to degenerative lesions. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39087–39095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:609–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg ME, Xu B, Lu B, Hempstead BL. New insights in the biology of BDNF synthesis and release: implications in CNS function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12764–12767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3566-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasenstaub A, Otte S, Callaway E, Sejnowski TJ. Metabolic cost as a unifying principle governing neuronal biophysics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12329–12334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914886107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenz T, Diaz F, Spiegelman BM, Moraes CT. Activation of the PPAR/PGC-1alpha pathway prevents a bioenergetic deficit and effectively improves a mitochondrial myopathy phenotype. Cell Metab. 2008;8:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Cheng A, Hou Y, Mattson MP. Mitochondria and neuroplasticity. ASN Neuro. 2010;2:243–256. doi: 10.1042/AN20100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nisoli E, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis by NO yields functionally active mitochondria in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405432101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herzig S, et al. CREB controls hepatic lipid metabolism through nuclear hormone receptor PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2003;426:190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature02110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vo N, Goodman RH. CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13505–13508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obermeier A, et al. Identification of Trk binding sites for SHC and phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and formation of a multimeric signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22963–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgering BM, Coffer PJ. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 1995;376:599–602. doi: 10.1038/376599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franke TF, et al. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell. 1995;81:727–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segal RA, Greenberg ME. Intracellular signaling pathways activated by neurotrophic factors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:463–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Signal transduction by the neurotrophin receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:213–21. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin CH, et al. A role for the PI-3 kinase signaling pathway in fear conditioning and synaptic plasticity in the amygdala. Neuron. 2001;31:841–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orban PC, Chapman PF, Brambilla R. Is the Ras-MAPK signalling pathway necessary for long-term memory formation? Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sweatt JD. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:173–83. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barco A, Pittenger C, Kandel ER. CREB, memory enhancement and the treatment of memory disorders: promises, pitfalls and prospects. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2003;7:101–14. doi: 10.1517/14728222.7.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mattson MP. Glutamate and neurotrophic factors in neuronal plasticity and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1144:97–112. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nisoli E, et al. Mitochondrial biogenesis in mammals: the role of endogenous nitric oxide. Science. 2003;299:896–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1079368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klinge CM. Estrogenic control of mitochondrial function and biogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:1342–1351. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikonenko I, Boda B, Steen S, Knott G, Welker E, Muller D. PSD-95 promotes synaptogenesis and multiinnervated spine formation through nitric oxide signaling. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1115–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarthy MM. Estradiol and the developing brain. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:91–124. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stranahan AM, et al. Voluntary exercise and caloric restriction enhance hippocampal dendritic spine density and BDNF levels in diabetic mice. Hippocampus. 2009;19:951–961. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khabour OF, Alzoubi KH, Alomari MA, Alzubi MA. Changes in spatial memory and BDNF expression to concurrent dietary restriction and voluntary exercise. Hippocampus. 2010;20:637–645. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maswood N, et al. Caloric restriction increases neurotrophic factor levels and attenuates neurochemical and behavioral deficits in a primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18171–18176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405831102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duan W, et al. Dietary restriction normalizes glucose metabolism and BDNF levels, slows disease progression, and increases survival in huntingtin mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2911–2916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halagappa VK, et al. Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction ameliorate age-related behavioral deficits in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuccato C, et al. Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington’s disease. Science. 2001;293:493–498. doi: 10.1126/science.1059581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qin W, Haroutunian V, Katsel P, Cardozo CP, Ho L, Buxbaum JD, Pasinetti GM. PGC-1alpha expression decreases in the Alzheimer disease brain as a function of dementia. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:352–361. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tapia-Arancibia L, Aliaga E, Silhol M, Arancibia S. New insights into brain BDNF function in normal aging and Alzheimer disease. Brain Res Rev. 2008;59:201–220. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng B, et al. PGC-1α, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(52):52ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen SD, et al. Protective effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma coactivator-1alpha against neuronal cell death in the hippocampal CA1 subfield after transient global ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:605–613. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Handschin C, Rhee J, Lin J, Tarr PT, Spiegelman BM. An autoregulatory loop controls peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha expression in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7111–7116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232352100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]