INTRODUCTION AND BIOLOGY

The Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, a short chromosome 22, results from the reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 that fuses the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) gene on chromosome 22 to the Ableson (ABL) gene on chromosome 9.1,2 The protein product of the fusion gene, BCR-ABL, has enhanced tyrosine kinase activity leading to the constitutive activation of a number of downstream pro-proliferative and pro-survival signaling pathways, and hence to leukemogenesis.3 The Ph chromosome is the most frequent cytogenetic abnormality in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), occurring in approximately 20% to 30% of adults but only in about 5% of children with this disease.4 The incidence rises with age and it occurs in approximately 50% of patients older than 50 years.5

Depending on the location of the breakpoint within the BCR gene, two major varieties of the oncogenic protein of differing sizes have been recognized. The smaller P190bcr-abl protein is found in over two thirds of patients with Ph+ ALL and the larger p210bcr-abl protein, typical of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) but is also encountered in about a third of Ph+ ALL patients.6 In experimental models, the p190bcr-abl protein has a higher tyrosine kinase activity and is more efficient in stimulating the growth of lymphoid cells.6,7 However, using traditional chemotherapy regimens, clinical outcomes in patients carrying either of the two proteins have been generally similar.6,8

TREATMENT OF ADULTS AND CHILDREN WITH PH+ ALL

Historical perspectives

Prior to the introduction of imatinib, the outcome of patients with Ph+ ALL was poor. Although complete remission (CR) could be achieved in a the majority the of patients (60%–90%), the median CR duration was considerably shorter than that seen in patients with Ph- disease, leading to very few long term survivors. (Table 1) This was, to some degree, age-dependent with better survival reported in children with Ph+ ALL, particularly for those with a good initial response to glucocorticoid therapy.9,10. On the other end of the age spectrum, specifically those older than 50–60 years of age, the outcome was particularly dismal with high treatment-related mortality, low CR rates and short disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS).5,11,12

Table 1.

Selected chemotherapy trials in Ph+ ALL

| Reference | Ph+, N (%) | CR % | Median EFS/CRD (months) | Median OS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloomfield97 | 29 (17) | 46 | 7 | 11 |

| Gotz98 | 25 | 76 | NA | 8 |

| Larsen99 | 30 (27) | 70 | 7 | 11 |

| GFCH100 | 127 (29) | 59 | 5 | NA |

| Secker-Walker101 | 40 (11) | 83 | 13 | 11 |

| Wetzler102 | 67 (29) | 79 | 11 | 16 |

| Faderl103 | 67 (13) | *55, 90 | *8, 10.8 | *11.3, 16.5 |

| Dombret31 | 154 | 67 | **19% at 3 years | |

| Arico9 | 326 | 82 | ** 28% at 5 years | ** 40% at 5 years |

| Schrappe10 | 61 (1) | 75 | ** 38% at 5 years | ** 49% at 5 years |

GFCH: Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique ; CR :complete remission ; EFS : event-free survival ; CRD : complété rémission duration ; OS : overall survival ;

results for the VAD and hyperCVAD regimens quoted, respectively;

estimated survival at X years

The relatively uniform dismal prognosis in adult patients with Ph+ ALL using conventional chemotherapy regimens meant that few predictors of outcome had been identified. However, it is notable that even with such suboptimal regimens, the degree of reduction of BCR-ABL transcripts after induction and consolidation was found to be a powerful predictor of disease response and survival.13 This may be indicative of the potential role for monitoring BCR-ABL transcript levels when using regimens containing tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo SCT) in first CR from a suitable donor has been the standard strategy in adult Ph+ ALL patients, given their poor outcome with chemotherapy alone. Several recent reports have better defined the feasibility and outcome of this strategy in the pre-imatinib era. The introduction of imatinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors has improved the likelihood of identifying a donor as these agents provide durable responses in patients thereby allowing for the conduct of the appropriate donor searches.

Management of patients with relapse after prior chemotherapy or transplant has been even more challenging with the main focus to induce a second CR and proceed with allo SCT.14 Second generation TKIs are becoming particularly useful in this setting as they have produced second CRs even in this group of patients with generally dire prognosis.

Imatinib and imatinib containing regimens

Imatinib in younger Ph+ ALL patients

With the introduction of effective tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the treatment of Ph+ ALL patients is undergoing a revolutionary transformation with improved outcomes not only for patients who are eligible for and are able to receive allo SCT but also for those who are not candidates for or are unable to undergo such treatment. In fact, for the first time, the role of transplantation in first CR has been questioned with early follow up of a number of studies demonstrating comparable outcomes for patients receiving imatinib containing regimens with and without a transplant in first CR.15–17

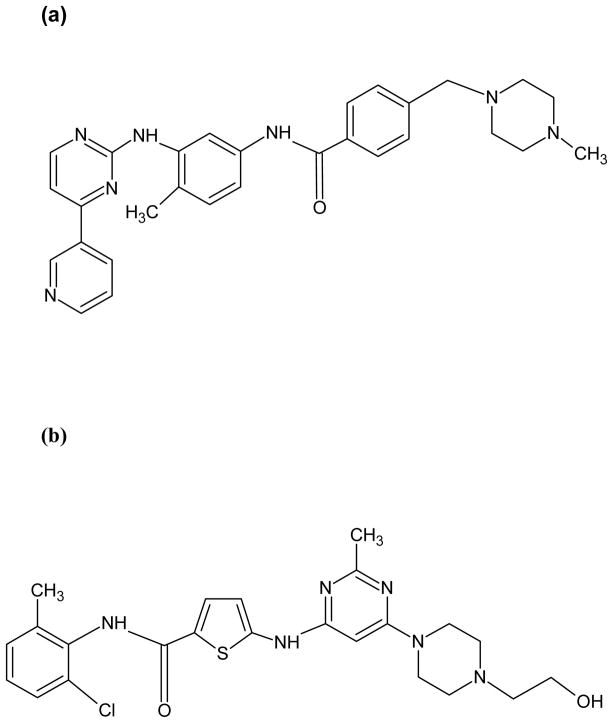

Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland) binds the inactive moiety of the bcr-abl kinase, partially blocking its ATP binding site, thereby preventing a conformational switch to the active tyrosine kinase (Figure 1a). Significant clinical activity and favorable toxicity profile of imatinib in Ph+ ALL was evident in the initial phase I and II trials of the drug.18–20 In the phase II study in patients with Ph+ ALL, imatinib induced CRs and complete marrow responses (marrow-CRs) in 29% of patients, which were sustained for at least 4 weeks in 6%.19 However, the median estimated time to progression and overall survival were short, 2.2 and 4.9 months, respectively.19 In a follow up study the extent of reduction in the BCR-ABL transcript levels in peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) analyzed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) in the treated patients was predictive of response and median time to progression.21 Other predictors of response such as pre-treatment white blood count (WBC), presence of circulating blasts prior to treatment, duration of prior CR, presence of a double Ph chromosome or up to 2 additional BCR-ABL fusion signals have also been reported.22 The probability of achieving complete hematological response (CHR) and response duration was higher in patients with a baseline WBC < 10 × 109/L, no circulating blasts pretreatment, a prior CR of at least 6 months, and no BCR-ABL amplification.22 Of interest, presence of additional chromosomal aberrations, or the size of the protein (p190 versus p210) did not affect the clinical outcome.

Figure 1.

(a) Imatinib, (b) Dasatinib

Therefore, from these early studies it was clear that few, if any, patients can achieve durable responses with single agent imatinib. At the same time, in vitro studies demonstrated synergistic or additive effects in Ph+ cell lines when imatinib was administered in combination with various chemotherapy agents, suggesting a potential role for these combinations in patients.23–25 Several investigators explored the efficacy of imatinib in combination with chemotherapy for frontline treatment of Ph+ ALL patients although initially the optimal schedule was debated and concurrent as well as sequential schedules were investigated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical trials incorporating imatinib into frontline chemotherapy for Ph+ ALL

| Reference | N | Median age (range) | Imatinib and chemo schedule | CR % | Relapse % | EFS % (years) | Survival % (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas15,26 | 45 | 51 (17–84) | Concurrent | 93 | 22 | 68* (3) | 55 (3) |

| Yanada16,28 | 80 | 48 (15–63) | Concurrent | 96 | 26 | 51 (2) | 58 (20 |

| Lee27 | 20 | 37 (15–67) | Concurrent | 95 | 32 | 62 (2) | 59 (2) |

| Lee42,43 | 29 | 36 (18–55) | Alternating | 79 | 4 | 78 (3) | 78 (3) |

| Wassmann29 | 45 | 41 (19–63) | Concurrent | * | * | 61 (2) | 43 (2) |

| 47 | 46 (21–65) | Alternating | * | * | 52 (2) | 36 (2) | |

| de Labarthe30 | 45 | 45 (16–59) | Concurrent | 96 | 19 | 51 (1.5) | 65 (1.5) |

| Delannoy33 | 30 | 66 (58–78) | Alternating | 72 | 60 | 58 (1) | 66 (1) |

| Vignetti32 | 30 | 69 (61–83) | +Prednisone | 100 | 48 | 48 (1) | 74 (1) |

| Ottmann34 | 28 | 68 (54–79) | Chemo→Concurrent | 96 | 41 | 29 (1.5) | 35 (1.5) |

| 27 | Imatinib→Concurrent | 50 | 54 | 57 (1.5) | 41 (1.5) |

CR: Complete remission; EFS: event-free survival;

CR duration reported

In the first clinical trial reporting the combination of imatinib with chemotherapy, imatinib 400 mg was administered daily for the first 14 days of each of the 8 cycles of the hyperCVAD regimen (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone, alternating with high dose cytarabine and methotrexate).15 This was followed by a maintenance phase where imatinib 600 mg was given continuously together with monthly vincristine and prednisone for 12 months.15 A CR rate of 96% with a 2-year DFS of 85% was reported. Half of the initial cohort of 20 patients underwent allo SCT. These were significantly superior results compared with historical data using chemotherapy alone. Furthermore, molecular complete responses, as analyzed by Q-PCR, were reported in 60% of the patients. Importantly, there was no unexpected toxicity related to the addition of imatinib to the regimen.

The same investigators have modified the regimen, with the final regimen including imatinib 600 mg on days 1–14 of induction, then 600 mg continuously with courses 2–8, followed by escalation to 800 mg as tolerated during 24 months of maintenance therapy with monthly vincristine and prednisone. Maintenance was interrupted by 2 intensification courses of hyper-CVAD and imatinib and after its completion imatinib was administered indefinitely. Allo SCT was performed in first CR as feasible. In a follow-up report in 54 patients with untreated or minimally treated disease, a CR rate of 93% was reported for those with active disease.26 Sixteen pts (33%) underwent allo SCT in first CR within a median of 5 months from start of therapy (range 1–13). In the untreated group, 14 patients with median age of 37 yrs underwent SCT in first CR whereas 33 patients with a median age of 53 years did not. The 3-year OS rates were similar (66% versus 49% with or without allo SCT, respectively, p=0.36). The 3-yr CR duration rate was 84% for patients who achieved molecular CR (2 of 16 had allo SCT) compared to 64% for those who did not (14 of 35 had allo SCT), p=0.1; OS rates were similar regardless of molecular CR status. With a median follow-up of 52 months (range 19–83+), 22% of the patients relapsed within a median of 15 months from the start of therapy (range 8–42), including two after allo SCT without imatinib maintenance.26

Other investigators have reported the results of studies incorporating imatinib into ALL chemotherapy regimens (Table 2). In general, trials designed for younger patients have added imatinib for varying lengths and doses to standard regimens whereas the emphasis in the older population has been to minimize poorly tolerated cytotoxic chemotherapy. The initial debates focusing on the optimal schedule, concurrent versus sequential imatinib, have been largely settled by several reports of good tolerability and improved efficacy of the concurrent treatment.

Lee et al reported on 20 patients with a median age of 37 years (range,15–67 years) with newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL who received an induction regimen of daunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and L-asparaginase together with imatinib 600 mg daily on days 1–14.27 Imatinib 400 mg daily was also administered in the first 14 days of each course of consolidation. After the first 12 patients, imatinib was administered continuously in both induction and consolidation cycles. Nineteen (95%) patients achieved CR and 15 underwent allo SCT in first CR.27 Median CR duration and median survival were significantly longer compared to a historical cohort of 18 patients treated with the same regimen but without imatinib.27 The reported toxicities of the regimen included reversible hyperbilirubinemia in 4 patients.

The Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group (JALSG) reported on a concurrent induction regimen of imatinib, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone.16,28 Consolidation therapy consisted of odd courses of high dose cytarabine and methotrexate, alternating with single agent imatinib 600 mg daily for 28 days. Patients then received 2 years of maintenance with imatinib, vincristine and prednisone. In the more recent report of 80 patients (median age 48 years, range, 15–63) a CR rate of 96% was reported.16 A PCR negative status was reported in 71% of patients at least at one point during their follow-up. Among the 57 patients who achieved PCR negativity, 17 patients had molecular relapse. Of them, seven patients had hematological relapse, six patients underwent allo SCT and four were in continuous CR without allo SCT. Allo SCT was conducted in 49 patients including 39 who underwent allo SCT in first CR. The 1-year event-free survival (EFS) and OS were estimated to be 60% and 76%, respectively, which were significantly better than historical controls treated without imatinib (p< 0.0001 for both). The probability of survival at 1 year was 73% and 85% for those who received or did not receive allo SCT, respectively.

In order to establish the best strategy of incorporating imatinib into ALL chemotherapy, The German Multicenter Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GMALL) trial evaluated 92 patients (median age 46 years, range 21–65 years) in two schedules.29 Imatinib was administered alternating with chemotherapy cycles in the first cohort of patients; then it was administered concurrently with chemotherapy throughout the second induction phase, consolidation and up to allo SCT in the second cohort. Prior to consolidation, PCR negativity rates of 52% and 19% were reported in the concurrent and alternating cohorts, respectively. A poor hematological response to the first induction cycle of chemotherapy was compensated by subsequent concurrent administration of imatinib with chemotherapy.29 In each cohort, 77% of patients underwent allo SCT and toxicity was acceptable for both schedules. The authors concluded that the concurrent regimen had a greater anti-leukemia efficacy. However, this greater activity did not translate to improvements in EFS and OS.29

In the Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GRAAPH) 2003 study imatinib was started with cytarabine and mitoxantrone (HAM) consolidation in good early responders (corticosteroid and chemosensitive ALL) or earlier during the induction course in combination with dexamethasone and vincristine in poor early responders (corticosteroid and/or chemoresistant ALL). Imatinib was then continuously administered until allo SCT.30 Overall CR and QPCR negativity rates were 96% and 29%, respectively. The CR rate was significantly higher compared to the previous report from the pre-imatinib era by the same group (96% versus 71%, p<0.001) and the DFS and OS were significantly longer (p=0.02, and 0.05, respectively).30,31 Furthermore, patients younger than 55 years were eligible for allo SCT and all 22 with a donor underwent SCT. Early results of a study by the Children’s Oncology Group where imatinib at 340 mg/m2 was administered for an increasing number of days in combination with an intensive chemotherapy backbone seems to confirm the benefit of the addition of imatinib even in the pediatric population and irrespective of the availability of a donor.17

Therefore, it is clear that the addition of imatinib to the initial therapy of patients with Ph+ ALL has significantly improved their outcome. Despite relatively short follow up and variations in the design and schedule of treatment, higher response rates, improved feasibility of allo SCT and improved EFS and OS rates were observed in all trials.

Imatinib in elderly Ph+ ALL patients

The question of more imatinib and less chemotherapy approach has been of particular interest in the elderly population who are less tolerant of the intensive chemotherapy regimens used in ALL, are less likely to be candidates for allo SCT, and comprise a significant portion of patients with this disease.12 Several trials have examined various approaches in this population (Table 2)

In the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) study, 30 patients with Ph+ ALL, 60 years and older, were treated with imatinib 800 mg as well as prednisone 40 mg/m2 daily from days 1 to 45.32 Twenty-nine were assessable for response and all (100%) achieved CR. Molecular CR was achieved only in 1 of the 27 evaluable patients.32 The median CR duration and survival were 8 months and 20 months, respectively.32 Fourteen patients relapsed after a median of 4 months (range, 3–28 months). Two patients died in CR and 13 were alive in continuous remission after a median of 10 months (range, 1–32 months).32 In a study by Group for Research on Adult Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (GRAALL), patients 55 years or older were treated with chemotherapy based induction after a pre-phase of steroids.33 This was followed by consolidation phase of steroids and imatinib and 10 maintenance blocks of alternating chemotherapy, including 2 imatinib containing blocks. Among the 30 patients treated, a CR rate of 72% was reported with additional patients achieving CR after salvage imatinib.33 The outcome was significantly better than in historical patients treated by the same group with the 1-year OS of 66% versus 43% (p=0.005), and 1-year relapse-free survival of 58% versus 11% (p=0.0003).

Ottmann et al conducted a randomized trial of imatinib monotherapy versus standard induction therapy in 55 patients with a median age of 67 years (Range, 54–79 years).34 The CR rate was 96% in the imatinib treated arm versus 50% in the patients receiving induction chemotherapy (p=0.0001). Severe adverse events were significantly more frequent during induction with chemotherapy. Patients in either treatment arm then received imatinib 600 mg daily in combination with all successive cycles of chemotherapy which were administered irrespective of response to induction. The estimated OS for all patients was 42% at 2 years with no significant difference between the 2 arms.34 The molecular CR rates did not differ with either approach but PCR negativity occurred earlier in the imatinib induction arm. Median DFS survival was significantly longer in the patients achieving PCR negative status (18.3 months versus 7.2 months, p=0.002)

Role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation before and after imatinib era

Pre-imatinib era

With the incorporation of imatinib and other TKIs in the treatment of Ph+ ALL, the role of allo SCT is undergoing transformation. In the past, it was the only strategy which had a significant curative potential. However, it was limited in its application by the availability of suitable donors, and by its diminished feasibility and effectiveness in older patients, those with co-morbid conditions, and those with active leukemia at the time of transplantation. The outcome after allo SCT in the pre-imatinib era has been better characterized by several recent reports. Laport et al reported the outcomes for the largest series to date of uniformly treated Ph+ ALL patients.35. From 1985–2005, seventy-nine patients with Ph+ ALL, with a median age of 36 years, received a matched sibling transplant following total body irradiation (TBI) and etoposide-based conditioning and cyclosporine-based graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. For patients transplanted in first CR, the 10-year overall survival (OS) and cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM) were 54% and 31%, respectively. Acute GVHD, grades 2–4, was noted in 35% of patients, with 13% of patients developing chronic extensive GVHD. Of note, patients transplanted with peripheral blood stem cells were twice as likely to develop chronic GVHD compared with patients who received bone marrow stem cells, confirming results of other randomized studies assessing the impact of stem cell source on transplant outcome.36,37 The median time to relapse was 12 months (range 1–27 months), and all deaths due to NRM occurred within 3 years of allo SCT.35

The results of single center studies have been corroborated in large, multicenter studies designed to prospectively assess the role of allo SCT in adult ALL patients. In the largest trial to date, 267 Ph+ ALL patients were treated between 1993 and 2004 as part of the MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993 study.38 Patients with Ph+ disease who were younger than 55 years and had achieved CR were assigned to a matched sibling or matched unrelated donor (MUD). Patients without a donor or with a performance status that prohibited allo SCT were eligible for randomization to continued chemotherapy versus autologous SCT; very few patients were actually randomized with the majority of patients receiving continued chemotherapy.38 The conditioning regimen for the allo SCTconsisted of TBI and etoposide, and a cyclosporine-based GVHD prophylaxis regimen was recommended; imatinib was not used in the patients reported in this series. Twenty-eight percent of patients received a matched-related or unrelated donor allo SCT in first CR. At 5 years, OS was 44% following sibling SCT, 36% following MUD SCT, and 19% following chemotherapy, with treatment-related mortality (TRM) of 27% following sibling SCT and 39% following MUD SCT.38 After adjusting for differences in age and WBC count at presentation in the two groups and after excluding chemotherapy-treated patients who relapsed or died before the median time to allo SCT, only relapse-free survival remained significantly better in the allo SCT group; the TRM rate became significantly lower for the chemotherapy group, and OS became non-significantly worse in the allo SCT group, underscoring the need to carefully weigh the benefit of disease control with the TRM associated with allo SCT An intention-to-treat analysis, using the availability of a matched sibling donor, showed no significant difference in survival between the two groups (34% with and 25% without a donor).38

The results of this trial are consistent with the conclusions of two earlier studies, the LALA-87 and LALA-94 trials, which were designed to prospectively evaluate the role of allo SCT in first CR.31,39 Analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis, the LALA-87 trial showed a statistically significant advantage for allo SCT versus chemotherapy for patients with high-risk ALL, including Ph+ patients, with 10-year survival rates of 44% and 11%, respectively. 39 In the follow-up LALA-94 trial, the advantage of allo SCT over chemotherapy in Ph+ ALL patients was confirmed (estimated survival at 3-years 37% versus 12%, p=.02).31 Furthermore, the advantage of a molecular response prior to SCT was demonstrated with 3-year survival estimated at 54% for the group achieving a negative PCR versus 19% for those remaining BCR-ABL positive.31 This is in agreement with studies in the pediatric population where the level of residual disease prior to allo SCT correlates with outcome after SCT.40,41

Post imatinib era

The incorporation of imatinib into standard ALL therapy has improved the ability to undergo allo SCT in first CR, resulting in improved OS rates of 43% to 78% at one to three years of follow-up.15,16,29,30 As discussed previously, even prior to imatinib, patients in molecular remission at time of allo SCT had a longer DFS.31 As a result, interim monotherapy with imatinib has been used to reduce the disease burden prior to allo SCT. 42,43 In a study by Lee et al, interim cycles of imatinib between induction and consolidation and between consolidation and allo SCT significantly improved the DFS and OS as compared to a historical group of patients treated with the same chemotherapy regimen but without imatinib.42,43 The patients’ BCR-ABL/ABL ratios declined by a median of 0.77 and 0.34 logs after each of the 2 cycles of imatinib.42,43 As a result, a significantly higher proportion of patients proceeded to allo SCT in first CR. Therefore, such interim imatinib therapy not only improves the likelihood of allo SCT to be conducted in Ph+ ALL patients but also allows it to occur in a more favorable status.44 Of note, thus far, the early results of studies incorporating imatinib into pre-transplant therapy have not demonstrated a clear survival difference between patients who receive an allo SCT for consolidation versus those who do not. 15,16,29,30 Thus, whether, consolidation with allo SCT in first CR will remain the standard of care for Ph+ ALL will depend on the durability of the remissions achieved with chemotherapy plus imatinib regimens.

Radich et al had shown that Ph+ ALL patients who remained PCR positive after allo SCT had a significantly higher incidence of relapse than PCR-negative patients.45 Therefore, use of imatinib in the post-transplant setting to eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD) has been investigated by several groups.46–48 In the study by Wassmann et al, 27 Ph+ ALL patients received imatinib 400 mg daily upon detection of MRD post SCT.47 The dose could be escalated to 600 mg and 800 mg in patients remaining PCR positive. BCR-ABL transcripts were undetectable in 14 (52%) of the patients, after a median of 1.5 months of imatinib therapy (range, 0.9–3.7 months). Failure to achieve a molecular remission within six weeks of starting imatinib predicted relapse, occurring in 12 of 13 (92%) patients at a median of 3 months. DFS in patients with molecular CR at 12 and 24 months was 91% and 54% as compared to only 8% in patients remaining MRD positive after 12 months.47 These data suggested the benefit of prophylactic administration of imatinib in the post allo SCT setting.48 Imatinib could be administered safely from the time of engraftment at a dose intensity comparable to that used in primary therapy. Similar strategies combining interferon and imatinib to maintain remission have also been investigated.49,50

As evident in the MRC UKALL XII/ECOG 2993 study, TRM overcomes any survival advantage for transplant in older patients. Since the incidence of ALL, particularly the Ph+ subtype, increases in adults over age 50 years, transplant approaches with reduced TRM such as non-myeloablative regimens are needed. Martino et al reported the largest series of non-myeloablative SCT in ALL.51 They reported a TRM of 23%, OS of 31%, and disease progression of 49% at 2 years among 27 patients, with median age 55 years. A higher relapse rate was observed for patients transplanted with overt disease versus those transplanted in CR (60% versus 33%, respectively). These data suggest that this strategy is feasible in older patients in CR, but must be validated in multicenter, prospective studies.

Beyond first remission, allo SCT is curative in only a small fraction of ALL patients with long-term OS ranging between 5–43%, the primary cause of failure being relapse (>50%).38,52–55 In a study of 60 adult patients with advanced ALL (primary refractory n=8, first relapse n=52), including 14 patients with Ph+ disease, those who did not undergo re-induction chemotherapy after relapse had a better outcome, with 5-year OS 47% versus 18%.55 The authors suggested that patients who did not undergo salvage chemotherapy prior to SCT sustained less TRM leading ultimately to a better outcome.55 Similarly, in the subset of patients who relapsed in the MRC ECOG/UKALL study, patients that were able to receive a matched sibling transplant had the best survival at 5 years (23%).56 Factors predicting a better outcome were young age (OS 12% for patients <20 years-old versus 3% for patients greater than 50 years-old) and long duration of first remission (OS 11% for CR1> 2 years versus 5% for CR1 <2 years). 56

With current induction regimens, only 5–10% of newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL adults fail to achieve remission with initial induction chemotherapy, and additional attempts at induction chemotherapy may be unsuccessful. Several studies suggest that patients with an HLA identical sibling can benefit if they proceed directly to allo SCT without undergoing a second attempt at induction therapy.57,58 In the largest study 38 patients with ALL failing to achieve remission received HLA identical sibling transplants without re-induction.57 Approximately 35% of these patients with refractory disease achieved long-term disease-free survival. A second study with 22 patients (5 with ALL) with refractory disease had a similar survival of 38% following HLA-matched sibling transplants.58 Other studies suggest lower survival rates of 20% or less for these refractory patients.57,59 Nevertheless, allogeneic transplant should be considered for patients with relapsed/refractory disease who otherwise have a dismal chance of long-term survival.

In conclusion, transplant offered superior disease control compared to chemotherapy in the pre-TKI era, and allo SCT with a matched sibling or unrelated donor was recommended for all patients in first CR. The addition of TKIs to standard ALL therapy appears to improve disease control, albeit with relatively short follow-up. Allo SCT in first CR remains standard, but older or frail patients may be monitored closely with quantitative PCR and transplanted at time of increasing BCR-ABL transcript levels. Alternatively, non-myeloablative transplants with an expected lower TRM may be considered. Allo SCT with matched sibling or unrelated donors should be recommended for all patients with primary refractory or relapsed disease. Furthermore, alternative donor transplants should be considered in these patients, despite their significant TRM and relapse rates of up to 40%. Small patient numbers and heterogeneity in remission status limit conclusions regarding the use of umbilical cord blood transplants. An estimated 20–50% of patients transplanted in remission can achieve long-term disease control; relapse and engraftment remain significant issues.60

Resistance to imatinib

Both acquired and intrinsic resistance to imatinib have been described in Ph+ ALL patients. Acquired imatinib resistance may be due to BCR-ABL-dependent mechanisms such as bcr-abl overexpression or mutations in the kinase domains (KD)(Table 3).61,62 Resistance may also arise through BCR-ABL independent mechanisms such as pharmacokinetic factors reducing the availability of imatinib within Ph+ cells, or through activation of alternative signaling pathways such as the Src-kinase related pathways.63–67

Table 3.

Reported potential mechanisms of resistance to imatinib

| Mechanisms related to cellular uptake and retention of imatinib |

| Increased MDR1 expression104 |

| Reduced hOCT1 mediated influx67,105 |

| Increased binding to α1-acid glycoprotein-1106 |

| BCR-ABL dependent mechanisms |

| BCR-ABL over-expression61 |

| BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations61,62 |

| BCR-ABL independent mechanisms |

| Activation of alternate signaling pathways such as Src65 |

| Clonal evolution107 |

| Miscellaneous |

| Non-compliance |

| Stem cell quiescence108 |

Although several KD mutations have limited consequence, those that interfere with imatinib binding to the bcr-abl protein have been identified as a major mechanism of acquired resistance in patients with CML.61,62,68 These include (1) mutations that directly impede contact between imatinib and bcr-abl, such as T315I and F317L and (2) mutations in the ATP-binding, P-loop or in the activation loop that alter the spatial conformation of the protein.61,62,69,70 Data on the frequency and spectrum of these mutations in Ph+ALL is more limited. Two early studies in patients with advanced Ph+ lymphoid leukemias identified 5 different KD mutations in 14 of 17 patients with acquired imatinib resistance.71,72 In one report E255K/V mutations were noted in 67% of patients but this was not confirmed by the other study.71,72 However, in these studies KD mutations occurring prior to initiation of therapy with imatinib that could potentially account for primary resistance were not identified. More recently, the same investigators, using a more sensitive cloning and sequencing strategy, were able to demonstrate the presence of low-level KD mutations in imatinib-naïve patients.73 In a follow-up study in a larger cohort of elderly patients enrolled into the GMALL randomized study,34 approximately 40% of patients with imatinib-naïve with no or minimal prior exposure to chemotherapy, harbored a small leukemic clone (allele frequency of 2%, range 0.1%–2%) with these mutations.74 The frequency of the mutant allele at the time of diagnosis was always below the level of detection by direct cDNA sequencing and ATP-binding P-loop mutations were the dominant type accounting for 83% of the mutations with the other 17% being T315I. Remarkably, pre-existence of mutations including T315I did not adversely affect the CR rate or the achievement of molecular CR when compared with patients who only had unmutated BCR-ABL at diagnosis.74 This raises the hypothesis that these clones were eradicated by chemotherapy.

Only the presence of T315I at diagnoses was associated with a more rapid relapse; however, nearly all of the patients with a detectable mutation at diagnosis relapsed as opposed to only 50% of patients with unmutated BCR-ABL. Among the patients who relapsed, 84% harbored mutations with the most frequent site of mutations being P-loop (58%) and T315I (19%). Comparing the mutations at diagnosis and relapse only 1 of 11 patients with detectable mutation at diagnosis had a switch. On the other hand, 67% of patients with no mutation at baseline were found to have a dominant mutant clone at relapse.74 Jones et al have also recently reported the presence of KD mutations in the majority of patients with relapsed disease following imatinib therapy.75 They were detected in 88% of patients who had received either imatinib (n=11) or dasatinib (n=1) and in 86% of patients who had had two or more prior TKI compared to none of the patients who never received TKIs.75 A limited spectrum of mutations, mostly Y253H, T315I, and F317L were noted and they were not present prior to treatment with TKIs in those with available samples. Other investigators have also reported a high frequency of mutations at relapse suggesting a pivotal role for the BCR-ABL KD mutations in acquired imatinib resistance in Ph+ ALL patients.75,76 Whether such acquired imatinib resistance is a result of outgrowth of small clones with mutant KD existing prior to the initiation of imatinib or the effect of selection leading to the emergence of mutations, after the initiation of and continuous exposure to TKIs, requires further studies.74,75

A new mechanism of resistance involves the expression of spliced isoforms of Ikaros (IKZF1).{Iacobucci, et al, Blood 2008} Ikzf1 functions as a critical regulator of normal lymphocyte development and is involved in the rapid development of leukemia in mice expressing non-DNA-binding isoforms.{Cobb and Smale, Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2005} The Ik6 isoform, lacking all four N-terminal zinc fingers responsible for DNA-binding, was detected in 43 of 47 (91%) Ph+ ALL patients resistant to imatinib or dasatinib.).{Iacobucci, et al, Blood 2008} In addition, the expression level of Ik6 correlated with the BCR-ABL transcript level. Restoring Ikzf1 function would be of great benefit in this condition.

Finally, stromal support was proposed as an additional mechanism of resistance to TKIs.{Mishra, et al, Cancer Res 2006} Cells with low expression of BCR-ABL were able to grow in the presence of stroma. The stromal effect did not require cell-cell contact and the stromal-cell derived factor 1α, the ligand to the chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), could substitute for the presence of the stromal cells. Interfering with the stroma-lymphoblast interaction, possibly by the CXCR4 inhibitor plerixafor (AMD3100), could be of benefit in eradicating Ph+ ALL cells.

Second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors

The development of resistance and intolerance to imatinib in Ph+ leukemias patients has fuelled the search for alternative, second generation inhibitors capable of overcoming the resistance.77–79 Dasatinib is a dual Src and Abl kinase inhibitor that binds both active and inactive moieties of the bcr-abl protein and is approximately 325 times more potent against the kinase in preclinical studies (Figure 1b).77 The inhibition of other kinases particularly Src may be important in overcoming imatinib resistance particularly in patients with lymphoid leukemias where Src kinase activity may be important in the pathogenesis of the disease.80 Dasatinib is active in vitro against all imatinib resistant BCR-ABL mutants with the notable exception of T315I.77 It has demonstrated significant activity in phase I and II studies in Ph+ leukemias patients who were resistant to or intolerant of imatinib. Cortes et al reported the results of a phase II trial where patients with blast phase of CML who had failed imatinib, were treated with dasatinib 70 mg orally twice daily.81 Among 42 patients with lymphoid blast phase, 31% achieved a major hematological response (HR) and 50% a major cytogenetic response, mostly CRs. Response rates were similar in patients with or without imatinib-resistant BCR-ABL mutations. Ottmann et al conducted a phase II study of dasatinib in 36 Ph+ ALL patients after failing imatinib.82 The median age of the patients was 46 years (range, 15 to 85 years). Major HR was achieved in 15 (42%) of patients and cytogenetic CR in 21 (58%). Six patients had a baseline T315I mutation and none responded but response rates were similar in patients with other mutations compared to those with no mutations.82 More recent data has suggested that administering dasatinib once daily in CML or Ph+ ALL patients produces similar responses and is associated with a better toxicity profile including a lower incidence of grade III and IV myelosuppression or pleural effusions.83 In another report it was suggested that this regimen was effective in achieving CR in patients who had relapsed from prior, mostly imatinib-based therapy.85

Based on the significant activity of dasatinib against BCR-ABL, and impressive data in patients with relapsed disease, we have conducted a phase II study of combining the hyperCVAD regimen with dasatinib, administered at 50 mg orally twice daily for the first 14 days of each of the 8 induction/consolidation chemotherapy cycles, as frontline therapy.84 Patients would then receive dasatinib continuously indefinitely with monthly cycles of prednisone and vincristine for the first 2 years. A lower dasatinib dose was chosen in order to avoid excessive myelosuppression when combined with intensive chemotherapy. Preliminary data has been recently reported demonstrating the feasibility of this regimen in both relapsed and previously untreated patients.84 Among 28 patients with newly diagnosed disease (median age 52 years, range, 21–79 years), 26 (93%) achieved CR after 1 course of treatment; 20 of 26 (81%) achieved a cytogenetic CR after 1 cycle and 19 (68%) achieved a major molecular response including 14 (50%) with molecular CR. With a median follow up of 10 months (range, 2–21 months), 21 were alive and 18 alive in CR, 2 died at induction and 3 died in CR; 5 patients had relapsed with a median CR duration of 47 weeks in the relapsing patients; 2 relapsing patients died.84 Of note, BCR-ABL mutations were identified in 4 of the 5 relapsing patients (including 3 with T315I and 1 with F359V).84

Early reports of ongoing studies have suggested improved outcomes in older patients using dasatinib-based regimens for newly diagnosed patients. In a study by the European Working Group on adult ALL (EWALL) patients older than 55 years received an induction schedule of vincristine and dexamethasone repeated weekly for 4 weeks followed by consolidation methotrexate and asparaginase alternating with cytarabine for a total of 6 cycles.86 Dasatinib was administered at 140 mg daily during the induction and at 100 mg/day sequentially during the consolidation and maintenance courses. A CR rate of 95% was reported in the first 22 patients treated. Only one relapse and 3 deaths in CR were reported at a median follow up of 3.6 months.86 In the GIMEMA LAL 1205 study, dasatinib 70 mg twice daily was administered for 12 weeks, in combination with prednisone and intrathecal chemotherapy, to treat adult patients with newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL.87 Among the first 48 patients (median age, 54 years, range, 24–76), 34 were evaluable for response and a CR rate of 100% was reported with no deaths attributable to treatment.87 With a median follow-up of 11 months, survival at 10 months was 81%. Nine patients had relapsed with 5 showing a T315I, 1 an E255K and 2 without mutations. Details of consolidation treatment were not provided.87

Existence of BCR-ABL mutations that may induce resistance to dasatinib is of significant concern.88 Mutations in the gatekeeper region of BCR-ABL, in particular T315I confer resistance to dasatinib (as well as imatinib and other available TKIs). Crystal studies have demonstrated that the aromatic ring in the side chain of phenylalanine 317 directly interacts with the pyrimidine and thiazole rings of dasatinib.89 Furthermore, in the in vitro saturation mutagenesis, several amino acid substitutions affecting residue 317 have been reported to induce dasatinib resistance including both the imatinib-resistant F317L and other variants like F317V, F317I, and F317S. In cellular assays, the F317L has been shown to induce an approximately 10-fold with respect increase of dasatinib IC50 to wild-type BCR-ABL.90 As with imatinib-based therapy, at present, it is not clear whether these mutants exist pre-therapy and dasatinib treatment induces their overgrowth or their development is a direct result of treatment with the TKIs. Other second generation TKIs including nilotinib and bosutinib as well other investigational agents have been evaluated in phase I and II trials. Of potential interest are agents with activity against the T315I mutants.

Central nervous system (CNS) disease

CNS involvement is relatively common in ALL with up to 6% of patients having evidence of involvement at diagnosis and without adequate prophylaxis, Up to 30% of patients will develop CNS disease during treatment and follow-up.91,92 However, with routine CNS-directed treatment, this risk has subsided to less than 10%. A number of recent studies have reported a relatively high incidence of isolated CNS relapse in Ph+ acute leukemias patients with generally unfavorable outcomes.93,94 In the study by Leis et al 5 of 24 (21%) of Ph+ acute leukemia (ALL or CML lymphoid blast phase) patients who were treated with imatinib and without intensive chemotherapy or specific CNS prophylaxis developed CNS disease despite achieving a CR.94 Simultaneous plasma and CSF imatinib levels were measured in 4 subsequent patients and imatinib levels were noted to be 2 logs lower in the CSF than in plasma, with the CSF levels being below the level required for bcr-abl inhibition. Another report confirmed an almost 100 fold lower imatinib level in the CSF compared with plasma in a patient with relapsed Ph+ ALL and concurrent CNS disease.95 These studies suggested that imatinib poorly penetrates the blood-brain barrier and underscore the need for adequate CNS directed therapy in patients receiving imatinib-based therapy. This may be, at least in part, because imatinib is a substrate for the drug efflux P-glycoprotein with the latter’s high expression in the CNS.

Imatinib and dasatinib have been compared in a preclinical mouse model of intracranial Ph+ leukemia for their ability to penetrate blood-brain barrier.96 Dasatinib has antileukemic activity in the multidrug resistant K562/ADM with a high expression of P-glycoprotein and as such may have a better penetrance of the blood-brain barrier.96 In the mouse model, dasatinib led to the regression of CNS disease and improved survival, whereas imatinib was unable to inhibit the intracranial tumor growth. Furthermore, clinical responses to dasatinib in patients with imatinib resistant disease involving the CNS have been reported with responses being durable in some patients.96 Furthermore, KD mutational analysis on the blasts from the CSF of 2 patients who experienced a CNS relapse while receiving dasatinib demonstrated the presence of dasatinib-resistant mutations suggesting a selection pressure further indicating its CNS penetration.96 Prospective studies evaluating the dasatinib CSF levels and its ability to decrease the incidence of CNS relapse are necessary to confirm these data.

Future challenges in Ph+ ALL

The introduction of effective TKIs in the treatment of Ph+ ALL has introduced several avenues of research in a disease that was hitherto difficult to treat. In the younger patients, the standard therapy should include combination of chemotherapy with one of the TKIs, likely imatinib but potentially dasatinib with further maturation of emerging data. In the older patients who are less able to tolerate intensive chemotherapy regimens, rationally designed combinations including dasatinib, in addition to the careful monitoring for response, MRD, and toxicity to decide upon the continuation of treatment may further improve the outcome. The emergence or resurgence of KD mutations, particularly those resistant to the available TKIs (such as T315I) is a significant concern that requires careful design of potential strategies to circumvent it. Several new TKIs are in development with potential efficacy against clones resistant to first and second generation TKIs including T315I mutants (Table 4). The role of allo SCT will likely continue to be refined incorporating TKI-based strategies before and after allo SCT to maximize the benefits from all of our therapeutic armamentarium against this disease.

Table 4.

Selected new agents being evaluated in Ph+ leukemias

| Drug | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|

| Bosutinib | Bcr-Abl and Src kinase inhibitor |

| Homoharringtonine | Inhibition of protein synthesis, induction of differentiation and apoptosis |

| PHA739358 | Bcr-Abl and Aurora kinase A, B, and C inhibitor |

| AP24534 | Bcr-Abl, FLT3, and FGF1-R inhibitor |

| DCC2036 | Bcr-Abl inhibitor (binds the “switch pocket” |

| XL228 | Bcr-Abl, Src and IGF1-R inhibitor |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. Chromosome studies on normal and leukemic human leukocytes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1960;25:85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowley JD. Letter: A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243:290–3. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley GQ, Van Etten RA, Baltimore D. Induction of chronic myelogenous leukemia in mice by the P210bcr/abl gene of the Philadelphia chromosome. Science. 1990;247:824–30. doi: 10.1126/science.2406902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlieben S, Borkhardt A, Reinisch I, et al. Incidence and clinical outcome of children with BCR/ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). A prospective RT-PCR study based on 673 patients enrolled in the German pediatric multicenter therapy trials ALL-BFM-90 and CoALL-05-92. Leukemia. 1996;10:957–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoelzer D. Advances in the management of Ph-positive ALL. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2006;4:804–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, Dhingra K, et al. Significance of the P210 versus P190 molecular abnormalities in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute leukemia. Blood. 1991;78:2411–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Ilaria RL, Jr, Million RP, et al. The P190, P210, and P230 forms of the BCR/ABL oncogene induce a similar chronic myeloid leukemia-like syndrome in mice but have different lymphoid leukemogenic activity. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1399–412. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gleissner B, Gokbuget N, Bartram CR, et al. Leading prognostic relevance of the BCR-ABL translocation in adult acute B-lineage lymphoblastic leukemia: a prospective study of the German Multicenter Trial Group and confirmed polymerase chain reaction analysis. Blood. 2002;99:1536–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arico M, Valsecchi MG, Camitta B, et al. Outcome of treatment in children with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:998–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrappe M, Arico M, Harbott J, et al. Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: good initial steroid response allows early prediction of a favorable treatment outcome. Blood. 1998;92:2730–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radich JP. Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:21–36. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson RA. Management of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in older patients. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:126–33. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pane F, Cimino G, Izzo B, et al. Significant reduction of the hybrid BCR/ABL transcripts after induction and consolidation therapy is a powerful predictor of treatment response in adult Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:628–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Manero G, Thomas DA. Salvage therapy for refractory or relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:163–205. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DA, Faderl S, Cortes J, et al. Treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia with hyper-CVAD and imatinib mesylate. Blood. 2004;103:4396–407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yanada M, Takeuchi J, Sugiura I, et al. High complete remission rate and promising outcome by combination of imatinib and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a phase II study by the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:460–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultz KR, Bowman WP, Slayton W, et al. Improved early event free survival (EFS) in children with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) with intensive Imatinib in combination with high dose chemotherapy: Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Study AALL0031. Blood. 2007;110:Abstract #4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, et al. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1038–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ottmann OG, Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, et al. A phase 2 study of imatinib in patients with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoid leukemias. Blood. 2002;100:1965–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champagne MA, Capdeville R, Krailo M, et al. Imatinib mesylate (STI571) for treatment of children with Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia: results from a Children’s Oncology Group phase 1 study. Blood. 2004;104:2655–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheuring UJ, Pfeifer H, Wassmann B, et al. Early minimal residual disease (MRD) analysis during treatment of Philadelphia chromosome/Bcr-Abl-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Abl-tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) Blood. 2003;101:85–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Scheuring UJ, et al. Early prediction of response in patients with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ALL) treated with imatinib. Blood. 2004;103:1495–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiesing JT, Ohno-Jones S, Kolibaba KS, et al. Efficacy of STI571, an abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in conjunction with other antileukemic agents against bcr-abl-positive cells. Blood. 2000;96:3195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kano Y, Akutsu M, Tsunoda S, et al. In vitro cytotoxic effects of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in combination with commonly used antileukemic agents. Blood. 2001;97:1999–2007. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topaly J, Zeller WJ, Fruehauf S. Synergistic activity of the new ABL-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 and chemotherapeutic drugs on BCR-ABL-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2001;15:342–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas DA, Kantarjian HM, Cortes J, et al. Outcome after frontline therapy with the Hyper-CVAD and Imatinib Mesylate regimen for adults with de novo or minimally treated Philadelphia Chromosome (Ph) positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) Blood. 2008;112:Abstract #2931. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, et al. Clinical effect of imatinib added to intensive combination chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1509–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Towatari M, Yanada M, Usui N, et al. Combination of intensive chemotherapy and imatinib can rapidly induce high-quality complete remission for a majority of patients with newly diagnosed BCR-ABL-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:3507–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Goekbuget N, et al. Alternating versus concurrent schedules of imatinib and chemotherapy as front-line therapy for Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) Blood. 2006;108:1469–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Labarthe A, Rousselot P, Huguet-Rigal F, et al. Imatinib combined with induction or consolidation chemotherapy in patients with de novo Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the GRAAPH-2003 study. Blood. 2007;109:1408–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-011908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dombret H, Gabert J, Boiron JM, et al. Outcome of treatment in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia--results of the prospective multicenter LALA-94 trial. Blood. 2002;100:2357–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vignetti M, Fazi P, Cimino G, et al. Imatinib plus steroids induces complete remissions and prolonged survival in elderly Philadelphia chromosome-positive patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia without additional chemotherapy: results of the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA) LAL0201-B protocol. Blood. 2007;109:3676–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-052746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delannoy A, Delabesse E, Lheritier V, et al. Imatinib and methylprednisolone alternated with chemotherapy improve the outcome of elderly patients with Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the GRAALL AFR09 study. Leukemia. 2006;20:1526–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ottmann OG, Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, et al. Imatinib compared with chemotherapy as front-line treatment of elderly patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ALL) Cancer. 2007;109:2068–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laport GG, Alvarnas JC, Palmer JM, et al. Long-term remission of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from matched sibling donors: a 20-year experience with the fractionated total body irradiation-etoposide regimen. Blood. 2008;112:903–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Champlin RE, Schmitz N, Horowitz MM, et al. Blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic cells for allogeneic transplantation. IBMTR Histocompatibility and Stem Cell Sources Working Committee and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Blood. 2000;95:3702–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz N, Beksac M, Hasenclever D, et al. Transplantation of mobilized peripheral blood cells to HLA-identical siblings with standard-risk leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:761–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fielding AK, Rowe JM, Richards SM, et al. Prospective outcome data on 267 unselected adult patients with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia confirms superiority of allogeneic transplant over chemotherapy in the pre-imatinib era: Results from the international ALL trial MRC UKALLXII/ECOG2993. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiebaut A, Vernant JP, Degos L, et al. Adult acute lymphocytic leukemia study testing chemotherapy and autologous and allogeneic transplantation. A follow-up report of the French protocol LALA 87. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:1353–66. x. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krejci O, van der Velden VH, Bader P, et al. Level of minimal residual disease prior to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation predicts prognosis in paediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a report of the Pre-BMT MRD Study Group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:849–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goulden N, Bader P, Van Der Velden V, et al. Minimal residual disease prior to stem cell transplant for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:24–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S, Kim DW, Kim YJ, et al. Minimal residual disease-based role of imatinib as a first-line interim therapy prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2003;102:3068–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee S, Kim YJ, Min CK, et al. The effect of first-line imatinib interim therapy on the outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in adults with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2005;105:3449–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimoni A, Kroger N, Zander AR, et al. Imatinib mesylate (STI571) in preparation for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and donor lymphocyte infusions in patients with Philadelphia-positive acute leukemias. Leukemia. 2003;17:290–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radich J, Gehly G, Lee A, et al. Detection of bcr-abl transcripts in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia after marrow transplantation. Blood. 1997;89:2602–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderlini P, Sheth S, Hicks K, et al. Re: Imatinib mesylate administration in the first 100 days after stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:883–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wassmann B, Pfeifer H, Stadler M, et al. Early molecular response to posttransplantation imatinib determines outcome in MRD+ Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) Blood. 2005;106:458–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carpenter PA, Snyder DS, Flowers ME, et al. Prophylactic administration of imatinib after hematopoietic cell transplantation for high-risk Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:2791–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Visani G, Isidori A, Malagola M, et al. Efficacy of imatinib mesylate (STI571) in conjunction with alpha-interferon: long-term quantitative molecular remission in relapsed P-190(BCR-ABL)-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2002;16:2159–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wassmann B, Scheuring U, Pfeifer H, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate (Glivec) in combination with interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ALL) Leukemia. 2003;17:1919–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martino R, Giralt S, Caballero MD, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a feasibility study. Haematologica. 2003;88:555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, Storb R, et al. Influence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease on relapse and survival after bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical siblings as treatment of acute and chronic leukemia. Blood. 1989;73:1720–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doney K, Fisher LD, Appelbaum FR, et al. Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Multivariate analysis of factors affecting acute graft-versus-host disease, relapse, and relapse-free survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;7:453–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cornelissen JJ, Carston M, Kollman C, et al. Unrelated marrow transplantation for adult patients with poor-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: strong graft-versus-leukemia effect and risk factors determining outcome. Blood. 2001;97:1572–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terwey TH, Massenkeil G, Tamm I, et al. Allogeneic SCT in refractory or relapsed adult ALL is effective without prior reinduction chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:791–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109:944–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biggs JC, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al. Bone marrow transplants may cure patients with acute leukemia never achieving remission with chemotherapy. Blood. 1992;80:1090–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forman SJ, Schmidt GM, Nademanee AP, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation as therapy for primary induction failure for patients with acute leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1570–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.9.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grigg AP, Szer J, Beresford J, et al. Factors affecting the outcome of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for adult patients with refractory or relapsed acute leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:409–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marks DI, Aversa F, Lazarus HM. Alternative donor transplants for adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a comparison of the three major options. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:467–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293:876–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shah NP, Nicoll JM, Nagar B, et al. Multiple BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations confer polyclonal resistance to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571) in chronic phase and blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burger H, van Tol H, Boersma AW, et al. Imatinib mesylate (STI571) is a substrate for the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)/ABCG2 drug pump. Blood. 2004;104:2940–2. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas J, Wang L, Clark RE, et al. Active transport of imatinib into and out of cells: implications for drug resistance. Blood. 2004;104:3739–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donato NJ, Wu JY, Stapley J, et al. BCR-ABL independence and LYN kinase overexpression in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells selected for resistance to STI571. Blood. 2003;101:690–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.V101.2.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White DL, Saunders VA, Dang P, et al. OCT-1-mediated influx is a key determinant of the intracellular uptake of imatinib but not nilotinib (AMN107): reduced OCT-1 activity is the cause of low in vitro sensitivity to imatinib. Blood. 2006;108:697–704. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White DL, Saunders VA, Dang P, et al. Most CML patients who have a suboptimal response to imatinib have low OCT-1 activity: higher doses of imatinib may overcome the negative impact of low OCT-1 activity. Blood. 2007;110:4064–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Corbin AS, La Rosee P, Stoffregen EP, et al. Several Bcr-Abl kinase domain mutants associated with imatinib mesylate resistance remain sensitive to imatinib. Blood. 2003;101:4611–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hochhaus A, Kreil S, Corbin AS, et al. Molecular and chromosomal mechanisms of resistance to imatinib (STI571) therapy. Leukemia. 2002;16:2190–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Jones D, et al. Frequency and clinical significance of BCR-ABL mutations in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with imatinib mesylate. Leukemia. 2006;20:1767–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hofmann WK, Jones LC, Lemp NA, et al. Ph(+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia resistant to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 has a unique BCR-ABL gene mutation. Blood. 2002;99:1860–2. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.von Bubnoff N, Schneller F, Peschel C, et al. BCR-ABL gene mutations in relation to clinical resistance of Philadelphia-chromosome-positive leukaemia to STI571: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:487–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07679-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hofmann WK, Komor M, Wassmann B, et al. Presence of the BCR-ABL mutation Glu255Lys prior to STI571 (imatinib) treatment in patients with Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2003;102:659–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pfeifer H, Wassmann B, Pavlova A, et al. Kinase domain mutations of BCR-ABL frequently precede imatinib-based therapy and give rise to relapse in patients with de novo Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) Blood. 2007;110:727–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-052373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jones D, Thomas D, Yin CC, et al. Kinase domain point mutations in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia emerge after therapy with BCR-ABL kinase inhibitors. Cancer. 2008;113:985–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soverini S, Colarossi S, Gnani A, et al. Contribution of ABL kinase domain mutations to imatinib resistance in different subsets of Philadelphia-positive patients: by the GIMEMA Working Party on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:7374–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shah NP, Tran C, Lee FY, et al. Overriding imatinib resistance with a novel ABL kinase inhibitor. Science. 2004;305:399–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1099480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2542–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brown VI, Seif AE, Reid GS, et al. Novel molecular and cellular therapeutic targets in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoproliferative disease. Immunol Res. 2008;42:84–105. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cortes J, Rousselot P, Kim DW, et al. Dasatinib induces complete hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis. Blood. 2007;109:3207–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ottmann O, Dombret H, Martinelli G, et al. Dasatinib induces rapid hematologic and cytogenetic responses in adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia with resistance or intolerance to imatinib: interim results of a phase 2 study. Blood. 2007;110:2309–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Larson RA, Ottmann OG, Shah NP, et al. Dasatinib 140 mg once daily (QD) has equivalent efficacy and improved safety compared with 70 mg twice daily (BID) in patients with imatinib-resistant or -Intolerant Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL): 2-year data from CA180- 035. Blood. 2008;112:Abstract #2926. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ravandi F, Thomas D, Kantarjian H, et al. Phase II study of combination of hyperCVAD with dasatinib in frontline therapy of patients with Philadelphia chromosome (Ph) positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) Blood. 2008;112:Abstract #2921. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jabbour E, O’Brien S, Thomas DA, et al. Combination of the hyperCVAD Regimen with Dasatinib Is Effective in Patients with Relapsed Philadelphia Chromosome (Ph) Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) and Lymphoid Blast Phase Chronic Meyloid Leukemia (CML-LB) Blood. 2008;112:Abstract #2919. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rousselot p, Cayuela J-M, Recher C, et al. Dasatinib (Sprycel®) and chemotherapy for first-line treatment in elderly patients with de novo Philadelphia Positive ALL: Results of the first 22 patients Included in the EWALL-Ph-01 trial (on behalf of the European Working Group on Adult ALL (EWALL)) Blood. 2008;112:Abstract #2920. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Foà R, Vitale A, Guarini A, et al. Line treatment of adult Ph+ Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) patients. Final results of the GIMEMA LAL1205 study. Blood. 2008:Abstract #305. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Soverini S, Martinelli G, Colarossi S, et al. Presence or the emergence of a F317L BCR-ABL mutation may be associated with resistance to dasatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:e51–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tokarski JS, Newitt JA, Chang CY, et al. The structure of Dasatinib (BMS-354825) bound to activated ABL kinase domain elucidates its inhibitory activity against imatinib-resistant ABL mutants. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5790–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.O’Hare T, Walters DK, Stoffregen EP, et al. In vitro activity of Bcr-Abl inhibitors AMN107 and BMS-354825 against clinically relevant imatinib-resistant Abl kinase domain mutants. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4500–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cortes J. Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:145–62. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lazarus HM, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis: results from the international ALL trial MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2006;108:465–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pfeifer H, Wassmann B, Hofmann WK, et al. Risk and prognosis of central nervous system leukemia in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute leukemias treated with imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4674–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Leis JF, Stepan DE, Curtin PT, et al. Central nervous system failure in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia lymphoid blast crisis and Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with imatinib (STI-571) Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:695–8. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001625728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Takayama N, Sato N, O’Brien SG, et al. Imatinib mesylate has limited activity against the central nervous system involvement of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia due to poor penetration into cerebrospinal fluid. Br J Haematol. 2002;119:106–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Porkka K, Koskenvesa P, Lundan T, et al. Dasatinib crosses the blood-brain barrier and is an efficient therapy for central nervous system Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:1005–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bloomfield CD, Goldman AI, Alimena G, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities identify high-risk and low-risk patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1986;67:415–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gotz G, Weh HJ, Walter TA, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of the Philadelphia chromosome in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 1992;64:97–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01715353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Larson RA, Dodge RK, Burns CP, et al. A five-drug remission induction regimen with intensive consolidation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cancer and leukemia group B study 8811. Blood. 1995;85:2025–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic findings outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Group Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. Blood. 1996;87:3135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Secker-Walker LM, Prentice HG, Durrant J, et al. Cytogenetics adds independent prognostic information in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia on MRC trial UKALL XA. MRC Adult Leukaemia Working Party. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:601–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wetzler M, Dodge RK, Mrozek K, et al. Prospective karyotype analysis in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the cancer and leukemia Group B experience. Blood. 1999;93:3983–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Faderl S, Kantarjian HM, Thomas DA, et al. Outcome of Philadelphia chromosome-positive adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;36:263–73. doi: 10.3109/10428190009148847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mahon FX, Belloc F, Lagarde V, et al. MDR1 gene overexpression confers resistance to imatinib mesylate in leukemia cell line models. Blood. 2003;101:2368–73. doi: 10.1182/blood.V101.6.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Crossman LC, Druker BJ, Deininger MW, et al. hOCT 1 and resistance to imatinib. Blood. 2005;106:1133–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0694. author reply 1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gambacorti-Passerini C, Barni R, le Coutre P, et al. Role of alpha1 acid glycoprotein in the in vivo resistance of human BCR-ABL(+) leukemic cells to the abl inhibitor STI571. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1641–50. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.20.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wendel HG, de Stanchina E, Cepero E, et al. Loss of p53 impedes the antileukemic response to BCR-ABL inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7444–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602402103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Graham SM, Jorgensen HG, Allan E, et al. Primitive, quiescent, Philadelphia-positive stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia are insensitive to STI571 in vitro. Blood. 2002;99:319–25. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Iacobucci I, et al. Blood. 2008 Nov 1;112:3847. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.BS, Cobb ST, Smale Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;290:29. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26363-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mishra S, Zhang B, Cunnick JM, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Cancer Res. 2006 May 15;66:5387. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]