Abstract

Importance

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) indicates a chronic stress reaction in response to trauma, and is a prevalent condition that has been identified as a possible risk factor for obesity.

Objective

To determine if women who develop PTSD symptoms are subsequently more likely to gain weight and become obese relative to either trauma exposed women who do not develop PTSD symptoms or women with no trauma and no PTSD symptoms, and if effects are independent of depression.

Design and Setting

The Nurses' Health Study II (NHS II), a prospective observational study initiated in 1989 with follow-up to 2005, using a PTSD screener to measure PTSD symptoms and when they onset.

Participants

The sub-sample of the NHSII (n= 54,224; ages 24–44 years in 1989) in whom trauma and PTSD symptoms were measured.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Development of overweight and obesity using BMI cut-points 25.0 and 30.0kg/m2 respectively. Change in BMI during follow-up among women reporting PTSD symptom onset prior to 1989. BMI trajectory before and after PTSD symptom onset among women who developed PTSD symptoms during follow-up.

Results

Among women with ≥ 4 PTSD symptoms prior to 1989 (cohort initiation) BMI increased more steeply (b = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p< 0.001) over the follow-up. Among women who developed PTSD symptoms after 1989, BMI trajectory did not differ by PTSD status before PTSD onset. After PTSD symptom onset, women with ≥ 4 symptoms had a faster rise in BMI (b = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p< 0.000). The onset of ≥ 4 PTSD symptoms after 1989 was also associated with increased risk of becoming overweight or obese (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.19–1.56) among women who were normal weight in 1989. Effects were maintained after adjusting for depression.

Conclusions and Relevance

Experiencing PTSD symptoms is associated with increased risk of becoming overweight or obese, and PTSD symptom onset alters BMI trajectories over time. The presence of PTSD symptoms should raise clinician concerns about physical health problems that may develop and prompt closer attention to weight status.

Keywords: body weight changes, weight status, obesity, PTSD, stress, women

Obesity is a significant public health problem in the developed world, associated with increased likelihood of premature mortality and higher rates of morbidity.1,2 Among women, effects of obesity may be apparent at each stage of life (e.g., affecting reproductive health and outcomes, aging, life expectancy) and may have far-reaching effects in future generations.3,4 Numerous studies have documented associations between obesity and various forms of psychological distress.5,6 While some studies have failed to find a relationship,7,8 the preponderance of evidence suggests that severe forms of distress adversely influence weight status. Recent work has identified posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a marker of extreme distress occurring in response to a traumatic event and indicative of a chronic stress reaction,9 as a possible risk factor for weight gain and ultimately obesity.10–16 PTSD is prevalent especially among women; one in nine women will meet criteria for the diagnosis over their lifetime.17 Understanding the role of PTSD is important for interventions aimed at curbing weight gain and obesity treatment. However, whether PTSD is causally related to weight gain and obesity or is simply a co-morbid condition due to shared risk factors has not been established.

Most studies on PTSD and obesity are cross-sectional,14 and while they generally find positive associations, they cannot determine whether PTSD symptoms preceded development of obesity. In the only prospective study to date, among young women who were not overweight when PTSD was assessed, those with PTSD were at increased risk of becoming obese over six years of follow up.11 However, this study could not determine whether changes in PTSD status lead to changes in weight status over time. Demonstrating that PTSD symptom onset is associated with altered trajectory of weight gain would provide stronger evidence that PTSD is a risk factor for overweight and obesity.

The current study sought to determine if PTSD symptoms alter the trajectory of weight gain in a well-characterized sample of women. Using information on age of onset of PTSD symptoms, we considered weight status as measured by body mass index (BMI) both prior to and after onset of symptoms and examined whether women who develop symptoms are subsequently more likely to gain weight and become overweight or obese. Because there is debate on the relative role of trauma versus PTSD in pathophysiological processes, we considered effects of PTSD symptoms separately from effects of experiencing trauma, and hypothesized that women who develop PTSD symptoms will gain more weight than women who experience trauma but do not develop symptoms. Depression and PTSD are commonly comorbid, and other work has suggested that depression is also associated with weight gain.18 To address concerns about potential confounding, we also considered the primary associations after taking account of depressive status. Additional potential confounders were selected based on prior work15 suggesting demographic characteristics (e.g., age, marital status) and behaviors (e.g., cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption) may be related to both PTSD and weight status.

METHODS

Source and Study Population

The Nurses' Health Study II (NHSII) is an ongoing prospective cohort study of 116,671 female registered nurses that began in 1989. Participants are followed up via biennial questionnaires that gather information on health-related behaviors and medical events. For the present study, outcomes were assessed at 8 waves, with 87% of initially enrolled participants completing the 2005 questionnaire. The institutional review board at Brigham and Women's Hospital reviewed and approved this study, and participants provided consent.

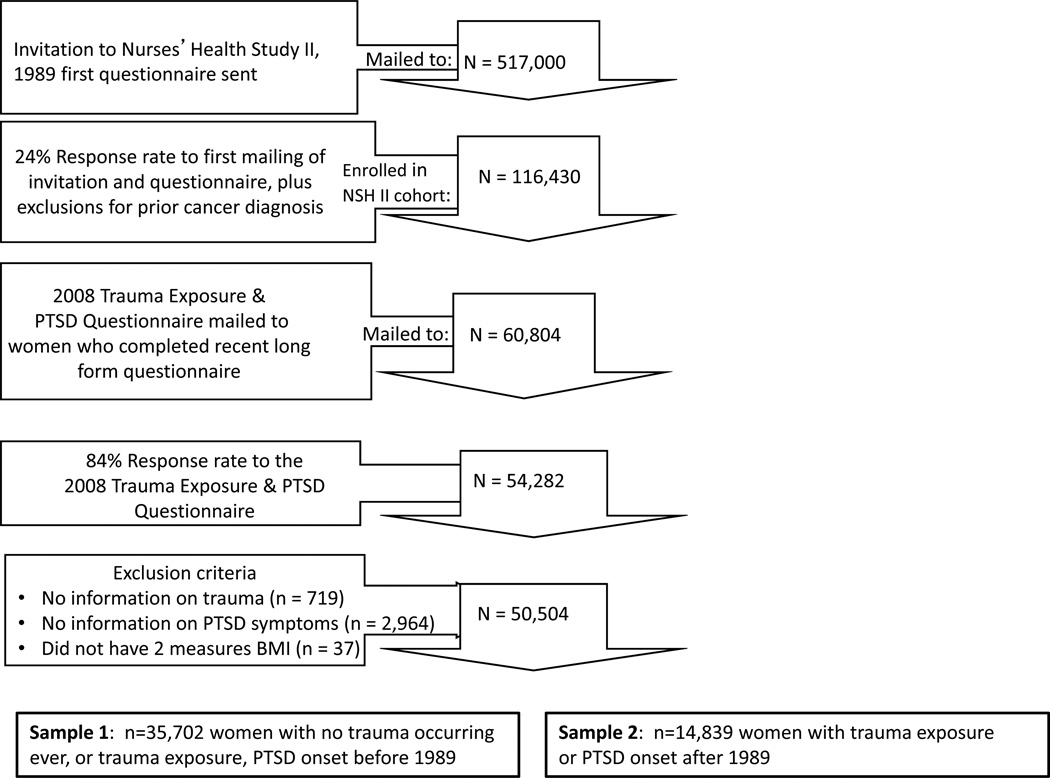

Data are from a subsample of the NHSII who participated in a supplemental study in 2008 (only participants responding to the longer form of the most recent biennial questionnaire = were asked to participate). The Trauma and PTSD Screening Questionnaire19,20 was mailed to 60,804 participants. The response rate was 84% (N = 54,224). Analysis was limited to 50,504 of these respondents after excluding women who provided no information on trauma (n=719), PTSD symptoms (n = 2,964) or at least one measure of BMI (n=37). Differences between included versus excluded women were minimal with regard to baseline age, childhood socioeconomic position (SEP) and regional distribution. The proportion of non-Hispanic whites was higher in the analytic versus original sample (95.7% vs. 93.8%), and the proportion of current smokers was lower (11.4% vs. 13.5%). These 50,504 women were divided into two separate groups for analysis depending on when trauma/PTSD occurred. Analytic sample 1 included women who reported having PTSD symptoms before or at the start of the cohort and women without PTSD or trauma through 2005 (N=35,702); analytic sample 2 included only women who reported either PTSD symptoms or worst trauma between 1989 and 2005 (N=14,839). Among women whose trauma/PTSD onset during the study follow-up period (Sample 2) assessments of BMI before and after onset of trauma/PTSD are available, facilitating direct evaluation of changes in BMI related to trauma/PTSD. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall Design for NHSII Study of PTSD and BMI. Modified from Roberts AL, Galea S, Austin SB, Cerda M, Wright RJ, Rich-Edwards JW, Koenen KC. Posttraumatic stress disorder across two generations: concordance and mechanisms in a population-based sample Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Sep 15;72(6):505–11.

Assessment of Trauma and PTSD

A modified version of the Brief Trauma Questionnaire (BTQ),21,22 included as part of the Trauma and PTSD Screening Questionnaire, was used to determine whether a woman met Criterion A1 for traumatic exposure according to the DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis.19 Breslau et al.'s 7-item screening scale for DSM-IV PTSD23 was used to identify PTSD symptomatology among women who met Criterion A1 for trauma exposure according to the BTQ. Endorsing 4 or more symptoms in relation to the worst trauma classifies PTSD cases with a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 93%, positive predictive value of 68%, and negative predictive value of 98%.23 Participants were asked to identify their worst event on the BTQ as this is a sensitive method for screening PTSD.24. Women reported the age at which the worst event occurred, and whether they experienced PTSD symptoms in relation to that trauma. They also reported the age they most recently had symptoms, from which remission status was determined for specific analyses.

Women were categorized according to whether they had no trauma, trauma but no PTSD symptoms, trauma with 1–3 PTSD symptoms (subclinical levels of PTSD), or trauma with 4 or more PTSD symptoms, the validated diagnostic cut-off. Date of onset of trauma and/or PTSD was the age at which the worst event was reported.

Assessment of Weight Status

Data on weight and height were collected with the 1989 questionnaire, and weight was further reported biennially. Self-reported weight was highly reliable (r = 0.97) among a subset of regionally residing participants who underwent direct measurement of their weight.25 We calculated BMI as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). To define normal weight, overweight and obesity, we used BMI cut-points 25.0 and 30.0kg/m2 respectively.26 Most participants had data on BMI at all follow-up periods (74%) with some women missing one (19%), two (5%) or 3 or more (2%) follow-up measurements.

Assessment of Covariates

In 1989, age and race was obtained. Region of residence at age 15 was assessed in 1993. Childhood SEP was assessed using a proxy of parental educational attainment, maximum of mother’s and father’s education at birth, reported in 2005. Participants self-classified their race, and for analytic purposes were categorized as white, black, Hispanic, other. Age, marital status (married, not married), alcohol consumption (0 g/day, 0.1–4.9 g/day, 5.0–14.9 g/day, 15+ g/day), and smoking status (never, former, current) were also updated with each questionnaire cycle. Lifetime history of depression (ever, never) was ascertained on the 2005 questionnaire.27

Statistical Analyses

Trauma/PTSD symptoms as a predictor of weight status was considered with several separate analyses. Initial analyses considered whether active or remitted PTSD symptoms versus no trauma or PTSD confer similar risk relative to the combined outcome of becoming either overweight or obese in 1989, using the full sample (N=50,290, excluding 251 without information on BMI in 1989). Logistic regression models were used to compare women with no trauma or PTSD symptoms to women with either current PTSD symptoms in 1989 or remitted PTSD symptoms in 1989. Additionally, using a subsample of Sample 2, we assessed the likelihood of being overweight/obese after experiencing trauma/PTSD symptoms, considering only women who experienced trauma/PTSD symptoms after 1989 and who reported normal weight on the questionnaire closest in time to when trauma occurred (n = 7,116). Models were adjusted for demographics and other covariates using PROC LOGISTIC in SAS 9.2.

To examine the timing of PTSD relative to weight gain, we conducted 1) hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) using repeated measures analysis (MPlus, version 5.1, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA) among women with PTSD symptom onset prior to or in 1989; 2) linear spline models to consider whether BMI rises more sharply after versus before PTSD symptom onset among only women who experienced trauma after 1989.

HLM analyses were conducted with Sample 1, women whose trauma/PTSD symptoms onset before 1989 or with no trauma/no symptoms. Women with no trauma or PTSD symptoms were compared with women who had trauma/no symptoms or trauma with 1–3 PTSD symptoms, or trauma with 4+ PTSD symptoms whose onset was reported prior to or occurring in1989 The spline analysis was conducted with Sample 2, women whose trauma/PTSD symptoms onset after 1989. Those with trauma/no PTSD served as the reference group compared with women with trauma and 1–3 PTSD symptoms or trauma and 4+ symptoms that onset after 1989. Each analysis involved three sets of models: a) trauma/PTSD only; b) a + age, race/ethnicity, region of residence at age 15, childhood SEP; c) b + lifetime history of depression, marital status + alcohol consumption + smoking status. Longitudinal multilevel models facilitate examination of how weight status changes over time within persons, and how that change is related to PTSD symptoms and their onset. Continuous BMI was modeled, and missing values of BMI do not pose a problem.28 Intercepts of the outcome at the 8 evenly spaced time points (2-year intervals) were fixed at zero. Means and variances of the growth factors were estimated with maximum likelihood, and an unstructured covariance model was used.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of participants by PTSD symptom status, including Samples 1 and 2. Through 2008, 18.6% of women experienced neither trauma nor PTSD symptoms, 30.3% experienced trauma but no symptoms, 30.6% experienced 1–3 symptoms and 20.5% experienced 4 or more symptoms. Compared with participants without PTSD symptoms, those with symptoms were more likely to be living in the South or West of the U.S. at age 15 and less likely to be living in the Northeast, were slightly older, had parents slightly more educated, had higher baseline BMI, were more likely to report lifetime depression, and were more likely to smoke.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (characterizing according to participants who reported PTSD symptoms before or on 1989, N=50504)

| No trauma and no PTSD Sx |

Trauma but no PTSD Sx |

Trauma and 1–3 PTSD Sx |

Trauma and 4+ PTSD Sx |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n, %) | 9392 | 18.6 | 15288 | 30.3 | 15447 | 30.6 | 10377 | 20.5 | |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F |

| Age at study entry | 34.6 | 4.7 | 34.8 | 4.7 | 34.9 | 4.6 | 34.9 | 4.5 | 8.54*** |

| BMI at study entry | 23.6 | 4.6 | 23.7 | 4.7 | 23.9 | 4.9 | 24.1 | 5.1 | 21.88*** |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | X2 | |

| Race/ethnicity | 1.69 | ||||||||

| White | 9038 | 96.2 | 14624 | 95.7 | 14734 | 95.4 | 9942 | 95.8 | |

| Black | 69 | 0.7 | 174 | 1.1 | 184 | 1.2 | 80 | 0.8 | |

| Hispanic | 109 | 1.2 | 237 | 1.6 | 277 | 1.8 | 170 | 1.6 | |

| Asian et al | 176 | 1.9 | 253 | 1.7 | 252 | 1.6 | 185 | 1.8 | |

| Region of residence at age 15 | 154.9*** | ||||||||

| Northeast | 3476 | 37.0 | 5541 | 36.2 | 5146 | 33.3 | 3413 | 32.9 | |

| Midwest | 3455 | 36.8 | 5317 | 34.8 | 5415 | 35.1 | 3572 | 34.4 | |

| South | 955 | 10.2 | 1764 | 11.5 | 1918 | 12.4 | 1345 | 13.0 | |

| West | 801 | 8.5 | 1473 | 9.6 | 1844 | 11.9 | 1244 | 12.0 | |

| Missing | 705 | 7.5 | 1193 | 7.8 | 1124 | 7.3 | 803 | 7.7 | |

| Parental education | 17.6*** | ||||||||

| Less than HS | 856 | 9.1 | 1614 | 10.6 | 1532 | 9.9 | 1092 | 10.5 | |

| HS | 3874 | 41.3 | 6160 | 40.3 | 6009 | 38.9 | 3844 | 37.0 | |

| Some college | 2136 | 22.7 | 3541 | 23.2 | 3692 | 23.9 | 2438 | 23.5 | |

| College | 2132 | 22.7 | 3309 | 21.6 | 3560 | 23.1 | 2438 | 23.5 | |

| Missing | 394 | 4.2 | 664 | 4.3 | 654 | 4.2 | 565 | 5.4 | |

| BMI categories | 53.5*** | ||||||||

| Normal weight BMI<25 | 6883 | 73.2 | 10998 | 71.9 | 10967 | 71 | 7173 | 69 | |

| Overweight, 25≤BMI<30 | 1617 | 17.2 | 2718 | 17.8 | 2716 | 17.6 | 1968 | 19 | |

| Obesity, BMI ≥30 | 858 | 9.1 | 1506 | 9.8 | 1697 | 11 | 189 | 11 | |

| Missing | 40 | 0.5 | 77 | 0.5 | 78 | 0.5 | 56 | 1 | |

| Lifetime depression | 2303.6*** | ||||||||

| Yes | 1097 | 11.7 | 1682 | 11 | 2856 | 18.5 | 3692 | 35.6 | |

| Missing | 369 | 3.9 | 576 | 3.8 | 562 | 3.6 | 525 | 5.1 | |

| Smoking status | 259.9*** | ||||||||

| Never smoked | 6754 | 71.9 | 10448 | 68.3 | 10123 | 65.5 | 6316 | 60.9 | |

| Past smoker | 1720 | 18.3 | 3172 | 20.8 | 3524 | 22.8 | 2624 | 25.3 | |

| Current smoker | 903 | 9.6 | 1648 | 10.8 | 1787 | 11.6 | 1425 | 13.7 | |

| Missing | 15 | 0.2 | 20 | 0.1 | 13 | 0.1 | 12 | 0.1 | |

Abbreviations: Sx – symptoms; SD – standard deviation; HS – high school

X2 (for categorical variables) and ANOVA (for continuous variables) were conducted to assess differences across trauma/PTSD groups

P-values: *<.05,

<.01,

<.001.

PTSD Symptoms and Risk of Overweight or Obesity

Among all women (samples 1 and 2) we evaluated the likelihood of being obese or overweight in 1989, after adjusting for demographics, considering trauma/PTSD status prior to 1989. Compared to women with no trauma or PTSD symptoms, neither women with trauma only (odds ratio [OR]=0.99, 95% CI=0.95–1.04), nor women with remitted symptoms (OR=1.03, 95% CI=0.96–1.09), demonstrated excess odds of overweight or obesity. Women with trauma and ongoing symptoms had significantly excess odds (1–3 symptoms: OR=1.15, 95% CI=1.08–1.23; 4+ symptoms: OR=1.26, 95% CI=1.18–1.35).

We then examined the odds of becoming overweight or obese among women who were normal weight at baseline and experienced trauma/ PTSD symptoms between 1989 and 2005. Women with 1 to 3 and 4+ PTSD symptoms had 18% (OR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.04–1.33) and 36% (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.19–1.56), respectively, increased odds of becoming overweight or obese in adjusted models compared to women with trauma-only. Results remained significant albeit slightly attenuated after adjusting for other covariates including depression.

PTSD Symptoms and Weight Gain

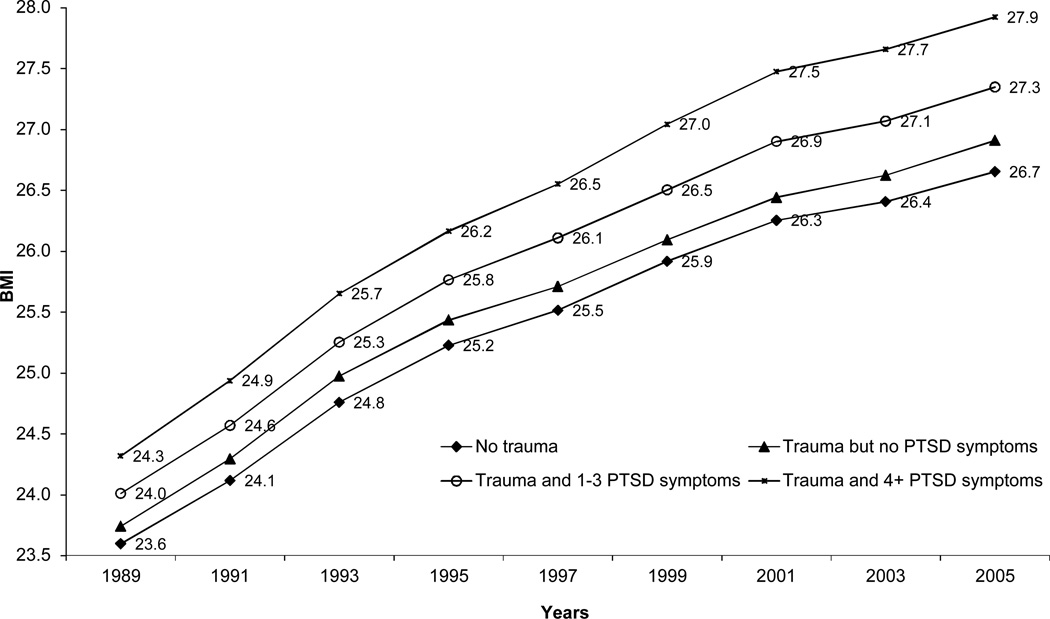

Unadjusted BMI trajectories over time indicate a faster rate of weight gain among women who experienced trauma or symptoms prior to study entry relative to women who never experienced trauma or PTSD (Figure 2). At every follow-up year women who initially reported trauma and symptoms had higher BMI even after controlling for all covariates including depression (intercept parameters, Table 2). Furthermore, a dose-response relation was evident. Higher PTSD symptoms were associated with greater BMI increases over time (slope parameters, Table 2). We also compared the steepness of BMI increase among women with trauma compared to those with and without PTSD symptoms. In fully adjusted models, compared with women with trauma and no symptoms, women with 1 to 3 symptoms (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p < 0.000), and with 4+ symptoms (b = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.000) demonstrated faster rates of BMI increase over the follow up period.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted mean BMI over time according to trauma/PTSD group (including women with trauma/PTSD prior to or in 1989 or who have no trauma/PTSD through 2005, n = 41,976)

Table 2.

Relationship between trauma/PTSD and BMI trajectory among participants who reported first PTSD symptom before or as occurring in 1989 (Nurses Health Study II, N=35,702)

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | p-value | b | S.E. | p-value | b | S.E. | p-value | |

| Intercept | |||||||||

| Trauma and PTSDd | |||||||||

| Trauma, no PTSD | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.002 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.226 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.089 |

| PTSD 1–3 Sx | 0.39 | 0.07 | <0.000 | 0.28 | 0.07 | <0.000 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.001 |

| PTSD 4 plus Sx | 0.69 | 0.08 | <0.000 | 0.60 | 0.08 | <0.000 | 0.31 | 0.08 | <0.000 |

| Slope | |||||||||

| Trauma and PTSDd | |||||||||

| Trauma, no PTSD | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.051 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.027 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.050 |

| PTSD 1–3 Sx | 0.04 | 0.01 | <0.000 | 0.04 | 0.01 | <0.000 | 0.03 | 0.01 | <0.000 |

| PTSD 4 plus Sx | 0.08 | 0.01 | <0.000 | 0.09 | 0.01 | <0.000 | 0.05 | 0.01 | <0.000 |

Abbreviations: Sx - symptoms

Model 1: PTSD and/or trauma only

Model 2: Model 1 + age at baseline (centered at 34 years old), race/ethnicity, region at age 15, childhood SEP

Model 3: Model 2 + depression status, smoking status, alcohol status, and marital status

Reference: No trauma and no PTSD

PTSD Symptoms and BMI Trajectory

By considering only women with PTSD symptom onset after entry into the study, we can evaluate whether PTSD symptoms alter BMI trajectories. Spline models that impose an inflection at the time PTSD symptoms onset indicate that BMI trajectory prior to symptom onset did not significantly differ from those with trauma who never develop symptoms. However, after PTSD symptom onset, women with 1 to 3 symptoms (b = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p = 0.002) and with 4+ symptoms had a faster rise in BMI (b = 0.08, SE = 0.02, p< 0.001) over time compared with women with trauma and no PTSD. This effect was maintained after adjusting for all covariates including depression (Table 3).

Table 3.

Spline models of the relation between trauma/PTSD and BMI trajectory including only participants who reported first PTSD symptom/worst event between 1989 and 2005 surveys. Inflection is set at trauma/PTSD onset (Nurses Health Study II, N=14,839).

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | p-value | b | S.E. | p-value | b | S.E. | p-value | |

| Interceptd | |||||||||

| PTSD 1–3 Sx | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.000 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.003 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.000 |

| PTSD 4 plus Sx | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.002 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.022 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.002 |

| Slope before PTSD onsetd | |||||||||

| PTSD 1–3 Sx | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.322 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.291 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.322 |

| PTSD 4 plus Sx | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.512 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.543 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.512 |

| Slope after PTSD onsetd | |||||||||

| PTSD 1–3 Sx | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.000 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.002 |

| PTSD 4 plus Sx | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.000 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.000 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.000 |

Model 1: PTSD and/or trauma only; reference group is trauma, no PTSD

Model 2: Model 1 + age at baseline (centered at 34 years old), race/ethnicity, region at age 15, childhood SEP

Model 3: Model 2 + depression status, smoking status, alcohol status, and marital status

Reference: Trauma but no PTSD

DISCUSSION

PTSD symptoms were associated with faster weight gain and increased risk of obesity in women. Moreover, these are the first findings to demonstrate that PTSD symptom onset is associated with altered BMI trajectories over time. Relative to women who did not experience trauma or PTSD symptoms at any time, women with PTSD symptom onset prior to 1989 had higher BMI at every follow-up assessment and their BMI increased at a faster rate. Among women whose trauma occurred after 1989 an altered BMI trajectory was evident: prior to symptom onset, BMI trajectories were comparable to women who did not subsequently develop PTSD symptoms, however after symptom onset, BMI increased at a faster rate. Previous studies have largely focused on the association of PTSD symptoms with weight status in combat veterans.13,14,29–33 This is the first study to examine the prospective relation of PTSD symptoms to BMI trajectories and obesity in women exposed to a wide range of traumatic events occurring in civilian settings.

Rigorous epidemiologic studies are increasingly showing that PTSD has significant implications for physical health.34–36 Moreover, it appears that effects of PTSD are not simply due to co-morbid depression, and even sub-clinical threshold PTSD levels should be considered as potentially increasing risk of subsequent health problems. The link between PTSD and obesity is of particular interest given that PTSD has been identified as a potential risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases,37–39 and obesity is a candidate mechanism by which these effects occur.

PTSD may influence weight gain by behavioral and biological mechanisms, and both may operate simultaneously. Recent studies have suggested PTSD is associated with physical inactivity,14 increased consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages,40 or generally dysregulated food intake related to dependence on activation of the brain reward system.41 In addition, dysregulated neuroendocrine function including enhanced negative feedback sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptors, blunted cortisol levels, and exaggerated catecholamine responses to trauma-related stimuli have all been found in adults diagnosed with PTSD39. Recent work has suggested that neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a likely mediator between PTSD and metabolic imbalances due to high exposure to sympathetic activation.11 Animal studies suggest that stress upregulates NPY which plays an important role in adipose tissue remodeling and development of abdominal obesity.42. Thus, high levels of distress may directly alter fat production and its distribution.

Strengths and Limitations

This investigation has numerous strengths including prospective data, a large study population, extensive data on potential confounding factors, and information on BMI prior to and after onset of PTSD symptoms. However, PTSD was assessed only in relation to the worst event which can result in some misclassification of timing of onset of PTSD; and trauma exposure, PTSD symptoms, and age of onset were assessed retrospectively, which can result in underestimating lifetime prevalence or psychopathology.43 In our sample, the prevalence of trauma exposure is comparable to other samples using DSM-IV diagnostic criteria44 but the prevalence of women reporting 4+ PTSD symptoms (20.5%) is somewhat higher17 possibly due to our use of a screen versus a diagnostic interview. Also, to limit concerns about potential confounding we adjusted for lifetime depressive status; however, a more refined assessment of confounding was not possible because we lacked information on timing of depression relative to PTSD symptom onset. Another limitation is generalizability, given our population of predominately White, female nurses. Finally, it is possible that confounding by some unmeasured variable could explain findings. However, this seems less likely given that observed associations were unchanged in analyses that considered BMI pre- and post-onset of PTSD symptoms whereby each woman served as her own comparison.

Conclusions

Studies have suggested that once obesity develops, it is difficult to treat.45 Thus, while PTSD is a significant concern for its effects on mental health, our findings also suggest that the presence of PTSD symptoms should raise clinician concerns about potential physical health problems that may develop. Thus, primary care settings that treat populations at high risk for trauma exposure may want to screen for PTSD and monitor patients for other sequelae. Findings from this study suggest that trauma will be most strongly associated with increased risk of weight gain if trauma leads to the development of PTSD symptoms, although future work may also want to consider type of trauma in this relationship more deeply.

Physicians may be more effective if they can recognize and manage this type of emotional distress. Our work may also suggest that women with PTSD should be monitored or screened for development of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes. In fact, our work highlights the importance of expanding PTSD treatments to attend to behavioral alterations – like changes in diet or exercise - that lead to obesity. Health behaviors are currently completely outside the scope of PTSD treatments. Moreover, our data provide initial evidence that if PTSD remits, adverse impacts on weight gain may be attenuated. With improved prevention, the potential for earlier intervention, and more effective treatment strategies, we may significantly improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MH078928 and MH093612 to Dr. Koenen. The Nurses' Health Study II is funded in part by NIH CA50385. We acknowledge the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School for its management of The Nurses' Health Study II. The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. We acknowledge the NHS study participants for their contribution in making this study possible.

Drs. Kubzansky and Koenen had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.”

Abbreviations

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- NHSII

Nurses’ Health Study II

- BMI

body mass index

- SE

standard error

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006 Aug 24;355(8):763–778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000 Apr 10;160(7):898–904. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulie T, Slattengren A, Redmer J, Counts H, Eglash A, Schrager S. Obesity and women's health: an evidence-based review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011 Jan-Feb;24(1):75–85. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan D. Obesity in women: a life cycle of medical risk. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007 Nov;31(Suppl 2):S3–S7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803729. discussion S31–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, Obesity, and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;67(3):220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;63(7):824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hach I, Ruhl UE, Klotsche J, Klose M, Jacobi F. Associations between waist circumference and depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2006 Jun;92(2–3):305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2003 Apr;27(4):514–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breslau N, Reboussin BA, Anthony JC, Storr CL. The structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: latent class analysis in 2 community samples. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005 Dec;62(12):1343–1351. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, Bush KR, Davis TM, Bradley KA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans: association with self-reported health problems and functional impairment. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004 Feb 23;164(4):394–400. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkonigg A, Owashi T, Stein MB, Kirschbaum C, Wittchen HU. Posttraumatic stress disorder and obesity: evidence for a risk association. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009 Jan;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott KM, McGee MA, Wells JE, Oakley Browne MA. Obesity and mental disorders in the adult general population. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008 Jan;64(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barber J, Bayer L, Pietrzak RH, Sanders KA. Assessment of rates of overweight and obesity and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in a sample of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Mil. Med. 2011 Feb;176(2):151–155. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Kazis LE. Association of psychiatric illness and obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking among a national sample of veterans. Psychosomatics. 2011 May-Jun;52(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Bodenlos JS, et al. Association of post-traumatic stress disorder and obesity in a nationally representative sample. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012 Jan;20(1):200–205. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roenholt S, Beck NN, Karsberg SH, Elklit A. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and childhood abuse categories in a national representative sample for a specific age group: associations to body mass index. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan A, Sun Q, Czernichow S, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and obesity in middle-aged and older women. Int. J. Obes. 2012 Apr;36(4):595–602. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan CA, 3rd, Hazlett G, Wang S, Richardson EG, Jr, Schnurr P, Southwick SM. Symptoms of dissociation in humans experiencing acute, uncontrollable stress: a prospective investigation. A. J. Psychiatry. 2001 Aug;158(8):1239–1247. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnurr P, Vielhauer M, Weathers FW. Brief Trauma Interview. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Sengupta A, Spiro A., 3rd A longitudinal study of retirement in older male veterans. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005 Jun;73(3):561–566. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnurr PP, Spiro AI, Velhauer MJ, Findler MN, Hamblen JL. Trauma in the lives of older men: Findings from the Normative Aging Study. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2002;8:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Kessler RC, Schultz LR. Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder. A. J. Psychiatry. 1999 Jun;156(6):908–911. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Poisson LM, Schultz LR, Lucia VC. Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychol. Med. 2004 Jul;34(5):889–898. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990 Nov;1(6):466–473. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. 1995:854. [PubMed]

- 27.O'Reilly EJ, Mirzaei F, Forman MR, Ascherio A. Diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero and depression in women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010 Apr 15;171(8):876–882. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JE. Applied longitudinal analysis. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Desai R, Kazis LE. Association of psychiatric illness and all-cause mortality in the National Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Psychosom. Med. 2010 Oct;72(8):817–822. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181eb33e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coughlin SS. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiovascular Disease. The open cardiovascular medicine journal. 2011;5:164–170. doi: 10.2174/1874192401105010164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coughlin SS, Kang HK, Mahan CM. Selected Health Conditions Among Overweight, Obese, and Non-Obese Veterans of the 1991 Gulf War: Results from a Survey Conducted in 2003-2005. The open epidemiology journal. 2011;4:140–146. doi: 10.2174/1874297101104010140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haskell SG, Gordon KS, Mattocks K, et al. Gender differences in rates of depression, PTSD, pain, obesity, and military sexual trauma among Connecticut War Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. J. Women's Health. 2010 Feb;19(2):267–271. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McFarlane AC. The long-term costs of traumatic stress: intertwined physical and psychological consequences. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association. 2010 Feb;9(1):3–10. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004 Dec;1032:141–153. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boscarino JA. A prospective study of PTSD and early-age heart disease mortality among Vietnam veterans: implications for surveillance and prevention. Psychosom. Med. 2008 Jul;70(6):668–676. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817bccaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC. Is posttraumatic stress disorder related to development of heart disease? An update. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2009 Apr;76(Suppl 2):S60–S65. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Jones C, Eaton WW. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in women. Health Psychol. 2009;28(3):364–372. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.28.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Spiro A, 3rd, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;64(1):109–116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanitallie TB. Stress: a risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism. 2002;51(6) Suppl 1:40–45. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirth JM, Rahman M, Berenson AB. The association of posttraumatic stress disorder with fast food and soda consumption and unhealthy weight loss behaviors among young women. J. Women's Health. 2011 Aug;20(8):1141–1149. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol. Behav. 2007 Jul 24;91(4):449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuo LE, Kitlinska JB, Tilan JU, et al. Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nat. Med. 2007 Jul;13(7):803–811. doi: 10.1038/nm1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol. Med. 2010 Jun;40(6):899–909. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol. Med. 2011 Jan;41(1):71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institutes of Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. 1998:98–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.