Abstract

Objective

A substantial proportion of chronically stressed informal caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients report experiencing fatigue. The objective of this study was to examine whether personal mastery moderates the relationship between caregiving status (caregiver/non-caregiver) and multiple dimensions of fatigue.

Methods

Seventy-three elderly Alzheimer’s caregivers and 41 elderly non-caregivers completed the short form of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory (MFSI-SF) and questionnaires assessing mastery.

Results

Regression analyses indicate that global fatigue scores were significantly higher for caregivers (M = 38.0 ± 21.0) compared to non-caregivers (M = 18.2 ± 10.4). However, personal mastery moderated the relations between caregiving status and global fatigue (t = −2.03, df = 107, p = .045), such that for those with low mastery, caregivers’ fatigue scores were 18.1 points higher than non-caregivers, and for those with high mastery, this difference was only 7.5 points. For specific dimensions of fatigue, mastery moderated the relations between caregiving status and both Emotional (t = −2.01, df = 107, p = .047) and Physical (t = −2.51, df = 107, p = .014) fatigue. Specifically, association between caregiving status and emotional fatigue was greater when mastery was low than when mastery was high. In regards to physical fatigue, caregiving status was significantly associated with physical fatigue when mastery was low, but was not when mastery was high. Significant main effects were found between mastery and general fatigue and vigor.

Conclusion

Given the high proportion of caregivers who experience fatigue and the impact that fatigue can have on health; these findings provide important information regarding mastery’s relationship with fatigue and may potentially inform interventions aiming to alleviate fatigue in caregivers.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Caregiving, Fatigue, Control, Coping, Exhaustion

Introduction

Fatigue is a common medical symptom experienced during or after many medical illnesses (Richardson, 1995, Mendoza et al., 1999, Ingles et al., 1999, Huet et al., 2000, Tack, 1990, Breslin et al., 1998, Hjollund et al., 2007) and also accompanies other non-medical circumstances such as depression and chronic psychosocial stress (Jensen and Given, 1993). Fatigue is one of the most distressing symptoms of many illnesses (Ingles et al., 1999), often resulting in reduced quality of life (Breslin et al., 1998, Ingles et al., 1999, Hann et al., 1999, Huet et al., 2000, Beiske et al., 2007) and reduced motivation and capacity to engage in cognitive, physical, and psychosocial activities (e.g., routine physical and recreational activities) (Lowder et al., 2005). Indeed, a study investigating the relations between 5 dimensions of fatigue (general, physical, reduced activity, reduced motivation, and mental) and quality of life, pulmonary function, and exercise tolerance in patients with COPD found that all 5 dimensions correlated with the functional impact dimension of quality of life (Breslin et al., 1998). Fatigue therefore has not only functional consequences but psychosocial ones as well.

Mechanisms underlying fatigue can be entirely physical in nature (i.e. resulting from disease progression, a physically-demanding lifestyle, or treatment regimen) and can also result from psychological stress (i.e. psychological or emotional strain), producing sustained physiological arousal and energy over-expenditure (Jensen and Given, 1993). One example of a population affected by both physical and psychological pathways is familial caregivers of patients with chronic diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Physically, caregivers are faced with demands involving assistance with daily activities and also report poorer sleep quality and increased daytime dysfunction compared to non-caregiving controls (McKibbin et al., 2005). Psychologically, the emotional strain of watching a loved-one progress through the stages of dementia and experiencing frustrations related to their spouse’s mental decline can be a steady source of physiological arousal leading to exhaustion (Jensen and Given, 1993).

Among dementia caregivers, fatigue is an especially critical health symptom considering that previous investigations report that up to 75% of caregivers experience chronic fatigue (Nygaard, 1988). In addition to the personal discomfort of fatigue, there are several consequences that can accompany fatigue. For example, fatigue has also been associated with intensified physical symptoms of pre-existing medical conditions in cancer (Curt et al., 2000), stroke (Ingles et al., 1999), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients (Breslin et al., 1998). Considering that Alzheimer caregivers are already susceptible to physical illness (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1991, Vitaliano et al., 2004, Vitaliano et al., 2003), fatigue may contribute to the exacerbation of existing physical symptoms. Furthermore, fatigue may contribute to the depletion of caregiving resources, which may factor into a caregiver’s decision to institutionalize their demented spouse (Chenoweth and Spencer, 1986, Rabins et al., 1982). Despite the impact that fatigue can have on the caregiving role, it has previously received mostly indirect attention in the dementia caregiving literature (Teel and Press, 1999).

Although fatigue is highly prevalent among familial caregivers (Nygaard, 1988, Lowder et al., 2005), it is important to note that despite the strains of caregiving, not all caregivers experience negative health consequences. Therefore, understanding the factors that contribute to caregiver resilience may help elucidate potential treatment targets for preventing or decreasing fatigue. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Model of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), health morbidity results from the interaction between external (i.e., environmental) stresses and internal resources (i.e., appraisals; coping). That is, when faced with a potential stressor, individuals make appraisals of whether the stressor is “threatening” and “challenging” and how well they believe they can cope with it. Therefore, caregivers’ morbidity (i.e., fatigue) depends not only on how much stress they experience, but on their appraisal of how well they can manage the stress. Within this framework, one resource factor that appears to modify the relationship between stress and morbidity outcomes is an increased sense of personal mastery, or a stronger belief that life circumstances are under one’s control. In particular, recent studies have found evidence to suggest that personal mastery may have a protective effect against the stresses of caregiving. In a 2006 study examining Alzheimer caregivers, Mausbach and colleagues found that caregiving stress was not related to global measures of psychological distress in caregivers reporting high levels of mastery (Mausbach et al., 2006). In contrast, among caregivers reporting low mastery, greater stress was associated with greater psychological distress. Identical results were found in a longitudinal study of medical and depressive symptoms in Alzheimer caregivers (Mausbach et al., 2007). Specifically, higher stress was significantly associated with greater report of depressive and medical symptoms only in caregivers with low personal mastery. In a third study by the same team, the relation between stress and the plasma concentration of type 1 Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor (PAI-1) antigen, a biomarker of increased cardiovascular risk indicating impaired fibrinolysis, was significant in caregivers with low, but not high mastery (Mausbach et al., 2008).

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that the relationship between caregiving status (caregiver vs. non-caregiver) and fatigue would be moderated by level of personal mastery. Specifically, we predicted that caregivers would report significantly greater levels of fatigue than non-caregivers when mastery was low, and that caregivers and non-caregivers would report similar levels of fatigue when mastery was high. Second, we explored whether this hypothesis was true for each of 5 subdomains of fatigue. Caregiving status alone was chosen to reflect caregiving stress rather than other indicators (e.g. dementia severity, problem behaviors, etc.) for several reasons. First, other indicators are highly collinear with caregiving status (caregiver vs. non-caregiver) by definition. Second, because caregiving stress is often difficult to define using one variable given its multi-dimensional nature, using caregiving status as our primary independent variable more completely captures caregiving stress as a whole. Allowing for generalization of this research, clinicians may be more likely to view patients dichotomously (i.e. caregiver vs. non-caregiver), and that the variation within caregivers on any one dimension, such as CDR, may be less salient. Therefore, it may be more useful to observe simple caregiver/non-caregiver differences when examining fatigue.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 73 participants providing in-home care to a spouse diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (i.e., caregivers) and 41 control participants who were married and whose spouses did not have a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease or other dementia (i.e., non-caregivers). All participants were enrolled in the University of California, San Diego Alzheimer Caregiver Project, which examined the effects of stress on health and well-being. Inclusion criteria included an age of 55 years or older, married, and living with the spouse. Caregivers and non-caregivers were excluded if they reported a serious or terminal medical condition (e.g., cancer, heart failure) or severe hypertension (BP > 200/120). Caregivers were recruited via Alzheimer caregiver support groups, health fairs, and referrals from either the UCSD Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) or by recommendation of other caregivers participating in the project. Most non-caregivers were recommended to participate by caregivers or were recruited through area health fairs. All participants provided written, informed consent, and the project was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Fatigue

All participants were administered the short form of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory (MFSI-SF) (Stein et al., 1998, Stein et al., 2004). The MFSI-SF consists of 30 questions asking the extent to which participants experienced various symptoms of fatigue over the past week. A 5-point Likert scale was used with items anchored at 0 = not at all and 4 = extremely. In addition to a global score, the MFSI-SF consists of 5 subscales representing the multidimensionality of fatigue. These subscales, each consisting of 6 items, are as follows: 1) General (e.g., “I feel pooped”); 2) Emotional (e.g., “I feel tense”); 3) Physical (e.g., “My body feels heavy all over”); 4) Mental (e.g., “I am unable to concentrate”); and 5) Vigor (e.g., “I feel lively”). Subscale scores are calculated by summing the individual items, and the global score is calculated by summing the five subscales (with the Vigor subscale reverse-scored).

The MFSI-SF has demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Stein et al., 2004), with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.87 – 0.96 for the subscales, indicating high interitem consistency. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis yielded high goodness of fit indices (CFI 0.90 and IFI 0.90), indicating high structural validity. Item loadings reflect a strong factor structure and ranged from 0.88–0.90 for general fatigue, 0.74–0.87 for emotional fatigue, 0.61–0.89 for mental fatigue, 0.67–0.85 for vigor, and 0.61–.83 for physical fatigue. This data from this study also supported strong concurrent and convergent validity. Although the measure was originally developed for and tested in cancer patients, the test constructors emphasize that the scales are useful for diverse populations due to the measure’s lack of reference to illness or diagnosis (Stein et al., 1998).

Personal Mastery

The Personal Mastery scale (Pearlin et al., 1990) was used, which consists of 7 items assessing participants’ belief they can control life events and circumstances (e.g., “There is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have”; “I have little control over the things that happen to me”; “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to do”). Responses were given on a 4-point scale from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” Two items are reverse scored and items are summed to create an overall score (range = 7–28), with higher scores indicating greater sense of mastery. The Personal Mastery Scale has also has been shown to have strong structural validity, with principal component factor loadings ranging from −0.47 to 0.76 (Pearlin and Schooler, 1978).

Sleep Quality

Because increased fatigue might be better explained by poor sleep quality (Kunert et al., 2007, Landis et al., 2003), all participants completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989). The PSQI assesses 7 components of sleep quality: 1) sleep quality, 2) sleep latency, 3) sleep duration, 4) habitual sleep efficiency, 5) sleep disturbance, 6) use of sleep medication, and 7) daytime dysfunction. A global score is created by summing the 7 component scores, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. This global score was used as a covariate in our analyses. The PSQI has been shown to have excellent psychometric properties (Carpenter and Andrykowski, 1998). In Carpenter and Andrykowski’s 1998 study, four samples reflecting four patient populations (bone marrow transplant patients, renal transplant patients, women with breast cancer, and women with benign breast problems) were administered the PSQI. Chronbach’s alphas were 0.80 across patient groups. Furthermore, correlations between global and component scores were moderate to high. The PSQI also demonstrated strong convergent and divergent validity.

Medical Symptoms

Considering the associations between fatigue and medical complaints (Yennurajalingam et al., In Press, Richardson, 1995, Mendoza et al., 1999, Ingles et al., 1999, Tack, 1990), participants were administered a medical history questionnaire assessing several medical symptoms (e.g., chest pain, abdominal discomfort, coughing, shortness of breath) typically assessed in a medical “review of systems.” Participants were asked to report whether or not they had experienced each of 14 symptoms over the past 6 months. A total score was created by summing the number of ‘yes’ responses. Although this measure has not been psychometrically validated, this measure was intended to assess the presence a list of commonly asked symptoms in the clinical setting. In order to ensure reliability of this measure, Cronbach’s alpha was assessed in the present sample.

Demographic Information

All participants answered questions assessing demographic information including their age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, and years married. Demographic data was also collected for the participant’s spouse, including age and years of education.

Data Analyses

T-tests and chi-square analyses were used to compare caregivers and non-caregivers on a number of linear and dichotomous demographic and health characteristics, respectively. Our primary analysis examined whether or not the relationship between caregiving status (caregiver vs. non-caregiver) and fatigue would be moderated by level of personal mastery. The moderator analysis approach described by Baron and Kenny (Baron and Kenny, 1986) and Holmbeck (Holmbeck, 1997, Holmbeck, 2002) was used. In this approach, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was used with global fatigue as our dependent variable and caregiving status and mastery as our primary independent variables. Prior to all analyses, all linear variables were centered at their means and all binary variables were dummy coded as suggested by Kraemer and Blasey (Kraemer and Blasey, 2004). Significant interactions between caregiving status and mastery were further tested for potential moderation by using the procedures described by Holmbeck (Holmbeck, 2002), in which plots for the relations between caregiving status and fatigue were created for low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of mastery and the simple slopes reflecting the relation between caregiving status and fatigue were tested at varying levels of fatigue. Because of their potential relationship with overall fatigue, age, medical symptoms, and sleep quality were included as covariates. A significant interaction between caregiving status and mastery was followed-up with post-hoc exploration of the nature of the interaction (see Holmbeck, 2002 for details on conducting these analyses).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Comparisons of caregivers and non-caregivers on demographic and health data are presented in Table 1. As seen, caregivers were significantly older and reported a greater number of medical symptoms, worse sleep quality, and lower mastery than non-caregivers. No other variables reached statistical significance. Correlations between study variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Variable | Caregivers (n = 73) | Non-caregivers (n = 41) | t, χ2 | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years), M (SD) | 72.16 (9.63) | 68.41 (6.68) | 2.44 | 106.93* | .016 |

| Female, n (%) | 54 (74) | 32 (78) | 0.24 | 1 | .628 |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 63 (86) | 40 (98) | .094† | ||

| Education, n (%) | |||||

| High school or less | 34 (47) | 23 (56) | 0.95 | 1 | .329 |

| More than high school | 39 (53) | 18 (44) | |||

| Years married, M (SD) | 37.85 (17.11) | 32.02 (18.58) | 1.69 | 112 | .094 |

| PSQI score, M (SD) | 7.42 (4.09) | 5.95 (3.15) | 2.15 | 101.11* | .034 |

| Personal Mastery, M (SD) | 18.65 (2.94) | 21.27 (2.87) | −4.60 | 112 | <.001 |

| Global Fatigue, M (SD) | 38.01 (20.96) | 18.22 (10.35) | 6.34 | 110.58* | <.001 |

| Spouse’s Characteristics | |||||

| Age, M (SD) | 77.19 (6.77) | 67.95 (9.94) | 5.09 | 53.46* | <.001 |

| Years of Education, M (SD) | 14.50 (3.90) | 15.61 (2.07) | −1.97 | 110.60* | .051 |

| CDR Score+, M (SD) | 2.67 (0.90) | 0.00 (0.00) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Fisher’s Exact test p-value.

Equal variances not assumed. PSQI = Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index.

CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating scale (range = 0–3).

n/a = not applicable, as non-caregivers were, by default, living with a spouse without Alzheimer’s Disease.

Table 2.

Spearman Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Global Fatigue | ||||||

| 2. Caregiving Status | .540† | |||||

| 3. Personal Mastery | −.604† | −.402† | ||||

| 4. Age | .047 | .241** | −.230* | |||

| 5. Medical Symptoms | −.406† | .181 | −.242** | .107 | ||

| 6. Sleep Quality | .501† | .164 | −.258** | −.032 | .409† |

Note. Correlations calculated from 114 individuals.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001

Reliability analyses were conducted on this sample for each measurement tool used. Chronbach’s alpha coefficients were as follows for each measure: 0.86 for the 30-item MFSI-SF, 0.77 for the 7-item Personal Mastery Scale, 0.73 for the 7 component scores of the PSQI, and 0.72 for the 14-item medical symptoms questionnaire. As a general rule of thumb, it has been proposed that alpha coefficients of 0.7–0.8 are satisfactory for comparing groups (Bland). Therefore these values indicate satisfactory internal consistencies for the purpose of this study.

Primary Analysis – Mastery as a Moderator of the Relations Between Caregiving Status and Fatigue

Our primary regression analysis explained 67.8% of the variance in overall fatigue scores (F = 37.50, df = 6, 107; p < .001). Age (β = −.15; t = −2.56, df = 107, p = .012), medical symptoms (β = .26; t = 3.86, df = 107, p < .001), and PSQI global sleep scores (β = .31; t = 4.81, df = 107, p < .001) were all significant predictors of fatigue and, as a whole, accounted for 45.8% of the variance. Caregiving status showed a significant main effect (β = .31; t = 4.59, df = 107, p < .001) suggesting that caregivers had worse fatigue than non-caregivers, but personal mastery did not relate to fatigue (β = −.18; t = −1.76, df = 107, p = .082). However, there was a significant caregiving status-by-mastery interaction (t = −2.03, df = 107, p = .045). Hierarchical linear regression analysis results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Regression Model Predicting Global Fatigue

| df | ΔF | p | ΔR2 | Entered Variables | B | SE | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 3,110 | 31.02 | <.001 | .458 | Intercept† | 31.43 | 1.42 | |

| Age | −0.07 | 0.16 | −0.03 | |||||

| Medical Symptoms† | 3.68 | 0.73 | 0.41 | |||||

| Sleep Quality† | 1.99 | 0.43 | 0.38 | |||||

| Step 2 | 5,108 | 33.39 | <.001 | .207 | Intercept† | 26.08 | 2.08 | |

| Age* | −0.34 | 0.13 | −0.15 | |||||

| Medical Symptoms† | 2.51 | 0.60 | 0.28 | |||||

| Sleep Quality† | 1.56 | 0.34 | 0.30 | |||||

| Caregiver† | 10.53 | 2.59 | 0.25 | |||||

| Mastery† | −2.22 | 0.41 | −0.35 | |||||

| Step 3 | 6,107 | 4.13 | .045 | .012 | Intercept† | 23.61 | 2.38 | |

| Age* | −0.33 | 0.13 | −0.15 | |||||

| Medical Symptoms† | 2.30 | 0.60 | 0.26 | |||||

| Sleep Quality† | 1.63 | 0.34 | 0.31 | |||||

| Caregiver † | 12.81 | 2.79 | 0.31 | |||||

| Mastery | −1.16 | 0.66 | −0.18 | |||||

| Caregiver X Mastery* | −1.66 | 0.82 | −0.19 |

Note. Intercept corresponds to the predicted global fatigue score for a caregiver where age was centered at 70 years, medical symptoms was centered at 23, sleep quality (PSQI Global Score) was centered at 7, and Mastery was centered at 19.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001

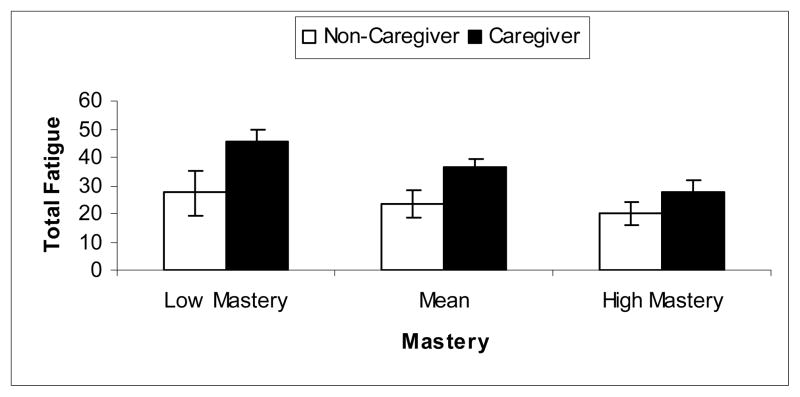

Post-hoc analyses indicated that caregiving status was more associated with fatigue when mastery was low (β = .43; t = 4.00, df = 107, p < .001) than when mastery was high (β = .18; t = 2.54, df = 107, p = .013). Specifically, when mastery was low (i.e. 1 SD below mean in this sample), caregivers’ fatigue scores were on average 18.1 points higher than non-caregivers. In contrast, when mastery was high (i.e. 1 SD above mean), this difference was only 7.5 points. Figure 1 shows mean and 95% confidence interval for caregivers and non-caregivers with low, medium, and high levels of mastery.

Figure 1.

Mean and 95% Confidence Interval for caregivers and non-caregivers with low, middle range, and high levels of personal mastery.

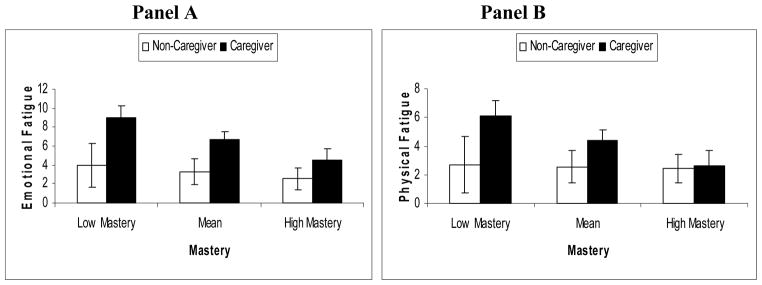

Secondary Analyses – Fatigue Subscales

Post-hoc analyses examined the relations between caregiving status, personal mastery, and the caregiving status-by-mastery interactions for each of the 5 subscales of the MFSI-SF. While there were no significant interactions for the General (t = −1.29, df = 107, p = .199), Mental (t = −0.83, df = 107, p = .410), and Vigor (t = 0.50, df = 107, p = .619) subscales, there was a main effect of mastery for the General (β = −.50; t = −3.75, df = 108, p < .001) and Vigor (β = .33; t = 4.00, df = 108, p = .001) subscales. That is, higher mastery was associated with lower general fatigue levels and an increased propensity for feeling energetic, lively, and cheerful, regardless of caregiving status. Graphic depictions of these main effects are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Relations between personal mastery and General Fatigue (panel A, left) and Vigor (panel B, right).

Significant interactions between caregiving status and mastery were observed for the remaining 2 subscales, namely Emotional (t = −2.01, df = 107, p = .047) and Physical (t = −2.51, df = 107, p = .014) fatigue. Post-hoc analyses indicated that there was a greater association between caregiving status and emotional fatigue when mastery was low (β = .48; t = 3.73, df = 107, p < .001) than when mastery was high (β = .18; t = 2.15, df = 107, p = .034). Interestingly, caregiving status was not significantly associated with physical fatigue when mastery was high (β = .02; t = 0.28, df = 107, p = .780), but was when mastery was low (β = .37; t = 3.08, df = 107, p = .003). Figure 3 shows mean emotional and physical fatigue scores (and 95% confidence intervals) by caregiving status and level of personal mastery.

Figure 3.

Mean (95% Confidence intercal) emotional (Panel A) and physical (Panel B) fatigue scores by caregiving status and level of mastery.

Discussion

Our results indicated that compared to non-caregivers, caregivers reporting high levels of personal mastery endorsed less overall fatigue than those reporting low mastery, after controlling for age, medical symptoms, and sleep quality. These results appeared particularly strong for both emotional (e.g., feeling sad, distressed) and physical (e.g., muscle aches, physical weakness) fatigue.

Caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients are expected to experience high levels of fatigue due to the daily mental, emotional, and physical demands placed on them. Indeed, caregivers must manage their loved-ones’ activities of daily living (e.g., dressing, toileting, shopping, eating) as well as cope with care recipient behavior problems such as forgetfulness, emotional outbursts, symptoms of psychosis, and wandering. The persistent experience of fatigue is an important physical outcome to monitor in Alzheimer’s caregivers because it may result not only in worsened quality of life and medical symptoms, but also in the caregiver burnout over time (Lowder et al., 2005).

Our findings are compatible with the Transactional Model of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) in that we examined the role of personal mastery in explaining what personal characteristics (i.e., personal mastery) might contribute to caregivers’ subjective experience of fatigue. Furthermore, these findings help elucidate the nature of mastery’s protective effect on specific dimensions of fatigue. Rose et al. define “protective factors” as factors that improve and negative outcome only in the context of adversity (i.e. caregiving) (Rose et al., 2004). These findings suggest that mastery serves as a protective factor in the relationship between caregiving status and global, emotional, and physical fatigue such that for these outcomes, mastery might exert a particularly positive impact for caregivers. In contrast, mastery serves as a “resource factor” in the relationship between caregiving status and general fatigue and vigor, in that mastery improves these outcomes regardless of caregiving status. The sum of these results suggests that mastery may have a potentially powerful relationship with the experience of fatigue and may help protect caregivers (as well as non-caregivers in some dimensions of fatigue) from experiencing deleterious outcomes.

Mastery likely exerts its effects in a number of ways. According to the Transactional Model of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), upon encountering stressors, individuals make primary appraisals involving the evaluation of the significance of the stressor to his/her well-being. Individuals then make secondary appraisals, involving the evaluation of the controllability of the stressor and his/her perceived ability to cope with it. Mastery may affect the primary appraisal of stressors and serve as a positive secondary appraisal. Caregivers high in personal mastery may appraise their care recipients’ problem behaviors as manageable or less threatening, or they may feel greater confidence in their ability to change or manage these behaviors. Secondly, high levels of mastery elicit goal-directed behavior and helps individuals persist in the face of obstacles or setbacks (Bandura, 2001). In the case of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease, it is possible that caregivers with high mastery may persist in social and recreational activities (e.g., exercise, hobbies), and such persistence has been linked with reduced experience of depression in a number of populations (Thompson et al., 2002, Williamson, 2000, Williamson and Schulz, 1992, Williamson and Schulz, 1995, Williamson et al., 1998). Mastery may also help caregivers persist in securing guidance and help when they are needed (e.g., medical care, support from friends/family). Help from these sources may lift the burden of caregiving, if even temporarily, and thereby help reduce fatigue.

While the results of this study point toward a potentially beneficial effect of mastery, this study was not experimental in nature, thereby limiting any causal interpretation of the results. Because our data are cross-sectional, we cannot determine whether mastery attenuates the experience of fatigue, if greater fatigue produces decreases in mastery, or if these constructs feed off each other to form a “vicious cycle”. However, within the context of caregiving research, experimental manipulation of mastery might be achieved through systematically testing the impact of a psychosocial intervention on the experiences of mastery and fatigue. While many psychoeducational and behavioral interventions for caregivers have been tested (for reviews, see (Brodaty et al., 2003, Sörensen et al., 2002)), burden and depression are almost exclusively the primary outcomes for these interventions. Indeed, very few studies have examined the impact of these interventions for increasing feelings of mastery or fatigue. One study, conducted by Coon and colleagues (Coon et al., 2003) found that cognitive-behavioral interventions significantly increased self-efficacy in caregivers, which in turn was associated with decreased depressive symptoms. Given that depression is conceptualized, in part, as experiencing increased lethargy (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), it seems likely that these interventions might also reduce feelings of fatigue by way of increasing mastery.

In sum, the present study found that personal mastery is associated with reduced overall experience of fatigue. Despite the daily stresses associated with being a caregiver, caregivers with high mastery had significant reductions in both emotional and physical fatigue. Also, personal mastery was associated with significantly greater vitality (e.g., feeling lively, refreshed, and energetic) and lower general fatigue in both caregivers and non-caregivers. Considering the large portion of caregivers who experience fatigue and the substantial impact that fatigue can have on physical and mental health, these findings provide important information on a possible target for decreasing the experience of fatigue among stressed caregivers.

Acknowledgments

Primary research support was provided via funding from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) through award AG15301. Additional support was provided by NIA award AG031090.

References

- AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- BANDURA A. Social Cognitive Theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARON RM, KENNY DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEISKE AG, NAESS H, AARSETH JH, ANDERSEN O, ELOVAARA I, FARKKILA M, HANSEN HJ, MELLGREN SI, SANDBERG-WOLLHEIM M, SORENSEN PS, MYHR KM. Health-related quality of life in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis. 2007;13:386–392. doi: 10.1177/13524585070130030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRESLIN E, VAN DER SCHANS C, BREUKINK S, MEEK P, MERCER K, VOLZ W, LOUIE S. Perceptions of fatigue and quality of life in patients with COPD. Chest. 1998;114:958–964. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRODATY H, GREEN A, KOSCHERA A. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:657–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUYSSE DJ, REYNOLDS CF, MONK TH, BERMAN SR, KUPFER DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for Psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARPENTER JS, ANDRYKOWSKI MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1998;45:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENOWETH B, SPENCER B. Dementia: The experience of family caregivers. The Gerontologist. 1986;26:267–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COON DW, THOMPSON L, STEFFEN A, SOROCCO K, GALLAGHER-THOMPSON D. Anger and depression management: Psychoeducational skill training interventions for women caregivers of a relative with dementia. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:678–689. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURT GA, BREITBART W, CELLA D, GROOPMAN JE, HORNING SJ, ITRI LM, JOHNSON DH, MIASKOWSKI C, SCHERR SL, PORTENOY RK, VOGELZANG NJ. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: New findings from the Fatigue Coalition. The Oncologist. 2000;5:353–360. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANN DM, GAROVOY N, FINKELSTEIN B, JACOBSEN PB, AZZARELLO LM, FIELDS KK. Fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation: A longitudinal comparative study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1999;17:311–319. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HJOLLUND NH, ANDERSEN JH, BECH P. Assessment of fatigue in chronic disease: A bibliographic study of fatigue measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLMBECK GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLMBECK GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUET P, DESLAURIERS J, TRAN A, FAUCHER C, CHARBONNEAU J. Impact of fatigue on the quality of life of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95:760–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INGLES JI, ESKES GA, PHILLIPS SJ. Fatigue after stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1999;80:173–178. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JENSEN S, GIVEN B. Fatigue affecting family caregivers of cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 1993;1:321–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00364970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIECOLT-GLASER JK, DURA JR, SPEICHER CE, TRASK OJ, GLASER R. Spousal caregivers of dementia victims: longitudinal changes in immunity and health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1991;53:345–62. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAEMER HC, BLASEY CM. Centring in regression analyses: A strategy to prevent errors in statistical inference. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:141–51. doi: 10.1002/mpr.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNERT K, KING ML, KOLKHORST FW. Fatigue and sleep quality in nurses. Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services. 2007;45:30–37. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070801-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDIS CA, FREY CA, LENTZ MJ, ROTHERMEL J, BUCHWALD D, SHAVER JL. Self-reported sleep quality and fatigue correlates with actigraphy in midlife women with fibromyalgia. Nursing research. 2003;52:140–147. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARUS RS, FOLKMAN S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- LOWDER JL, BUZNEY SJ, BUZO AM. The caregiver balancing act: Giving too much or not enough. Care Management Journals. 2005;6:159–165. doi: 10.1891/cmaj.6.3.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAUSBACH BT, PATTERSON TL, VON KÄNEL R, MILLS PJ, ANCOLI-ISRAEL S, DIMSDALE JE, GRANT I. Personal mastery attenuates the effect of caregiving stress on psychiatric morbidity. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:132–134. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198198.21928.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAUSBACH BT, PATTERSON TL, VON KÄNEL R, MILLS PJ, DIMSDALE JE, ANCOLI-ISRAEL S, GRANT I. The attenuating effect of personal mastery on the relations between stress and Alzheimer caregiver health: A five-year longitudinal analysis. Aging and Mental Health. 2007;11:637–644. doi: 10.1080/13607860701787043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAUSBACH BT, VON KÄNEL R, DEPP C, PATTERSON TL, ASCHBACHER K, MILLS PJ, GRANT I. The moderating effect of personal mastery on the relations between stress and Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) antigen. Health Psychology. 2008;27:S172–S179. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKIBBIN CL, ANCOLI-ISRAEL S, DIMSDALE JE, ARCHULETA C, VON KÄNEL R, MILLS PJ, PATTERSON TL, GRANT I. Sleep in spousal caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep. 2005;28:1245–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENDOZA TR, WANG XS, CLEELAND CS, MORRISSEY M, JOHNSON BA, WENDT JK, HUBER SL. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer. 1999;85:1186–1196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990301)85:5<1186::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYGAARD HA. Strain of caregivers of demented elderly people living at home. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 1988;6:33–37. doi: 10.3109/02813438809009287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARLIN LI, MULLAN JT, SEMPLE SJ, SKAFF MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–94. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARLIN LI, SCHOOLER C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RABINS PV, MACE NL, LUCAS MJ. The impact of dementia on the family. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1982;248:333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICHARDSON A. Fatigue in cancer patients: A review of the literature. European Journal of Cancer Care. 1995;4:20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1995.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSE BM, HOLMBECK GN, COAKLEY RM, FRANKS EA. Mediator and moderator effects in developmental and behavioral pediatric research. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25:58–67. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SÖRENSEN S, PINQUART M, DUBERSTEIN P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:356–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIN KD, JACOBSEN PB, BLANCHARD CM, THORS C. Further validation of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;27:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIN KD, MARTIN SC, HANN DM, JACOBSEN PB. A multidimensional measure of fatigue for use with cancer patients. Cancer Practice. 1998;6:143–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TACK BB. Self reported fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot study. Arthritis Care & Research. 1990;3:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TEEL CS, PRESS AN. Fatigue among elders in caregiving and noncaregiving roles. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21:498–514. doi: 10.1177/01939459922044009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON LW, SOLANO N, KINOSHITA L, COON DW, MAUSBACH B, GALLAGHER-THOMPSON D. Pleasurable activities and mood: Differences between Latina and Caucasian dementia family caregivers. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2002;8:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- VITALIANO PP, YOUNG HM, ZHANG J. Is caregiving a risk factor for illness? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- VITALIANO PP, ZHANG J, SCANLAN JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin. 2003;129:946–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMSON GM. Extending the activity restriction model of depressed affect: Evidence from a sample of breast cancer patients. Health Psychology. 2000;19:339–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMSON GM, SCHULZ R. Pain, activity restriction, and symptoms of depression among community-residing elderly adults. Journal of gerontology. 1992;47:367–72. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMSON GM, SCHULZ R. Activity restriction mediates the association between pain and depressed affect: A study of younger and older adult cancer patients. Psychology and aging. 1995;10:369–78. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMSON GM, SHAFFER DR, SCHULZ R. Activity restriction and prior relationship history as contributors to mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older spousal caregivers. Health Psychology. 1998;17:152–62. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YENNURAJALINGAM S, PALMER JL, ZHANG T, POULTER V, BRUERA E. Association between fatigue and other cancer-related symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0466-5. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]