Contrary to what some Americans seem to believe, the United States historically has been a polyglot nation containing a diverse array of languages. At the time of independence, non-English European immigrants made up one quarter of the population and in Pennsylvania two-fifths of the population spoke German.1 In addition, an unknown but presumably significant share of the new nation's inhabitants spoke an American Indian or African language, suggesting that perhaps a third or more of all Americans spoke a language other than English. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 (which doubled the size of the country), the Treaty of 1818 with Britain (which added the Oregon Country), the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 with Spain (which gave Florida to the U.S.), and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 (which acquired nearly half of Mexico), tens of thousands of French and Spanish speakers along with many more slaves and the diverse indigenous peoples of those vast territories were added to the linguistic mix.2 Alaska and Hawaii would follow before the end of the 19th century.

Although conquest clearly played a role in the 18th and 19th centuries, language diversity in the United States has been driven primarily by immigration. Germans and Celts entered in large numbers in the 1840s and 1850s, followed after the Civil War by Scandinavians in the 1870s and 1880s and then by Slavs, Jews, and Italians from the 1880s to the first decades of the 20th century. According to the 1910 census, which counted a national population of 92 million, 10 million immigrants reported a mother tongue other than English or Celtic (Irish, Scotch, Welsh), including 2.8 million speakers of German, 1.4 million speakers of Italian, 1.1 speakers of Yiddish, 944,000 speakers of Polish, 683,000 speakers of Swedish, 529,000 speakers of French, 403,000 speakers of Norwegian, and 258,000 speakers of Spanish.

Linguistic diversity began to wane with the cessation of mass European immigration, which ended abruptly in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, revived somewhat afterward, but then lapsed into a “long hiatus” during which flows were truncated by restrictive U.S. immigration quotas, a global depression, a second world war, and ultimately the transformation of Europe into a zone of immigration rather emigration.3 As a result, the percentage foreign born fell steadily in the United States, going from 14.7% in 1910 to reach a nadir of 4.7% in 1970,4 at which point language diversity had dwindled to the point where the Census Bureau stopped asking its question on mother tongue.

The great American paradox is that while the United States historically has been characterized by great linguistic diversity propelled by immigration, it has also been a zone of language extinction in which immigrant tongues die out to be replaced by monolingual English. Although ethnic identities may survive in some form into the third and fourth generations, immigrant languages generally suffer early deaths.5 This demise occurs not because of an imposition or compulsion from outside, but because of social, cultural, economic, and demographic changes within linguistic communities themselves.6 Based on an extensive study of America's historical experience, Calvin Veltman concluded that in the absence of immigration all non-English languages would eventually die out, usually quite rapidly.7

The revival of mass immigration after 1970 spurred a revival of linguistic diversity in the United States and propelled the nation back toward its historical norm. The postwar period in which older white Americans came of age was likely the most linguistically homogenous era in U.S. history. Compared to what came before and after, however, it was an aberration. The collective memory of those who grew up between 1944 and 1970 thus yields a false impression of linguistic practice in America. From a low of 4.7% in 1970, the percentage of foreign born rose steadily to reach 12.9% in 2010, much closer to its historic highs. Here we assess the effect of these new waves of mass immigration on language diversity in the United States and consider whether the sociohistorical reality of language extinction and English dominance will prevail in the 21st century.

The Return of Language Diversity

Language diversity refers to the number of languages spoken in the United States and the number of people who speak them. Since 1980 information on languages spoken has been gathered from three questions posed to census and survey respondents: Does this person speak a language other than English at home? What is this language? How well does this person speak English? Among other purposes, answers to these questions are used to determine bilingual election requirements under the Voting Rights Act. They were asked of all persons aged 5 and older on the censuses of 1980 through 2000 and in 2010 on the American Community Survey, which replaced the census long form. Table 1 summarizes these data by showing the share of U.S. residents who said they spoke a non-English language at home as well as the share who spoke only English by decade between 1980 and 2010. Since Spanish is by far the most widely spoken non-English tongue in the United States, we also report the share who speak Spanish at home.

Table 1. Language Use Patterns in the United States, 1980 to 2010.

| Languages spoken at home | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (millions) | % | N (millions) | % | N (millions) | % | N (millions) | % | Foreign-born % | |

| Total population 5 years or older | 210.2 | 100% | 230.4 | 100% | 262.4 | 100% | 289.2 | 100% | 13.6% |

| Spoke English only | 187.2 | 89.1 | 198.6 | 86.2 | 215.5 | 82.1 | 229.7 | 79.7 | 2.6 |

| Spoke non-English language | 23.1 | 11.0 | 31.8 | 13.8 | 47.0 | 17.9 | 59.5 | 20.3 | 56.7 |

| Spoke Spanish | 11.1 | 5.3 | 17.3 | 7.5 | 28.1 | 10.7 | 37.0 | 12.6 | 49.4 |

Sources: 1980, 1990 and 2000 U.S. censuses; 2010 American Community Survey.

As one would expect during an age of mass immigration, the percentage speaking only English at home has steadily fallen in recent decades, declining from 89.1% in 1980 to 79.7% in 2010, while the share speaking a language other than English correspondingly rose from 11% to 20.3%. In absolute numbers the number of persons 5 years and older speaking a language other than English at home rose from 23.1 to 59.5 million, with over two-thirds of the increase attributable to the increasing number of people speaking Spanish at home, who at 37 million comprised 12.6% of the total population but 62.2% of all non-English speakers in 2010. Most of the increase in Spanish language use was driven by mass immigration from Latin America. Indeed, most (56.7%) of the country's nearly 60 million speakers of non-English languages are immigrants. Among those who spoke only English at home in 2010, just 2.6% were born outside the United States (mostly immigrants from English-speaking countries); among those who spoke Spanish, half (49.4%) were foreign-born.

Table 2 examines the geography of foreign language use by showing the share of persons aged five and older speaking a non-English language at home in selected states and metropolitan areas. To create the list, we examined all 50 states and metropolitan areas with at least 500,000 inhabitants and ranked the top 25 according to the percentage of non-English speakers. The two lists clearly reveal that speaking a foreign language is a phenomenon of the nation's periphery rather than its heartland, concentrated in cities and states along the coasts, the Great Lakes, and the Mexico-U.S. border. Only four of the states on the list are neither on a coast, a lake or the border, and all of them were part of the Mexican Cession of 1848 (Nevada, Colorado and Utah in full, and Kansas in part). Kansas stands alone as the single heartland state on the list, with 10.6% of its population speaking a non-English language at home. California tops the list with 43.3% speaking a non-English language at home, followed by 36.1% in New Mexico, 34.5% in Texas, and 29.6% in New Jersey. The states listed in Table 2 clearly reflect the influence of mass immigration as the list includes the most important immigrant-receiving states (California, New York, New Jersey, Texas, Florida, and Illinois) as well as a number of emerging immigrant destinations (Arizona, North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, Utah, and Nevada). In sharp contrast, in a country where by 2010 over one in five persons (20.3%) spoke a foreign language at home, are the states of West Virginia, Mississippi, Kentucky, Montana, North Dakota and Alabama, where 95 to 98% of their populations spoke English only.

Table 2. Percent speaking a non-English language at home in selected states and metro areas, 2008-2010, in rank order.

| (population 5 years or older) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top 25 States | % | Top 25 Metros | % |

| California | 43.4 | McAllen, TX | 85.4 |

| New Mexico | 36.1 | El Paso, TX | 74.7 |

| Texas | 34.5 | Miami, FL | 73.0 |

| New York | 29.6 | Jersey City, NJ | 59.0 |

| New Jersey | 29.1 | Los Angeles, CA | 56.8 |

| Nevada | 28.8 | San Jose, CA | 50.8 |

| Arizona | 27.0 | New York, NY | 46.3 |

| Florida | 27.0 | Orange County, CA | 44.8 |

| Hawaii | 26.0 | Fresno, CA | 43.1 |

| Illinois | 21.9 | San Francisco, CA | 42.2 |

| Massachusetts | 21.5 | Bakersfield, CA | 41.0 |

| Rhode Island | 21.0 | Riverside, CA | 40.5 |

| Connecticut | 20.8 | Bergen-Passaic, NJ | 40.5 |

| Washington | 17.8 | San Antonio, TX | 40.2 |

| Colorado | 16.9 | Houston, TX | 38.8 |

| Maryland | 16.4 | Oakland, CA | 38.8 |

| Alaska | 16.0 | Ventura, CA | 37.4 |

| Oregon | 14.5 | Fort Lauderdale, FL | 37.1 |

| Virginia | 14.4 | San Diego, CA | 36.9 |

| Utah | 14.1 | Middlesex-Somerset, NJ | 34.4 |

| District of Columbia | 13.9 | Las Vegas, NV | 32.8 |

| Georgia | 12.9 | Dallas, TX | 32.1 |

| Delaware | 12.1 | Albuquerque, NM | 31.3 |

| Kansas | 10.6 | Vallejo-Faiifield-Napa, CA | 30.9 |

| North Carolina | 10.6 | Chicago-Gary, IL | 30.2 |

Source: American Community Survey (ACS), 2008-2010 merged files.

Language diversity, like immigration, is also chiefly a metropolitan phenomenon. Over 91% of the population of non-metropolitan areas in the U.S. speaks English only. The 25 metropolitan areas with the highest percentages of residents who speak a non-English language at home are confined entirely to the six gateway states, as shown in Table 2; the only exceptions are Las Vegas and Albuquerque. The largest shares of people living in homes where a language other than English is spoken are found, not surprisingly, in the large border metropolises of McAllen and El Paso, Texas, where the percentages speaking a non-English language at home were 85.4% and 74.7%, respectively (overwhelmingly Spanish). Other large shares of non-English speakers are observed in Miami (73.0%), Jersey City (59.0%), Los Angeles (56.8%) and San Jose (50.8%). Even at the bottom of the list, 30.2% of those in the Chicago metropolitan area speak a non-English language at home. Thus traditional and new gateway metropolitan areas are bastions of non-English usage.

The dominance of Spanish among foreign languages in the United States today sets the current age of mass immigration apart from earlier eras in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1910, for example, the most common non-English language, German, was listed as the mother tongue by just 20.7% of the foreign-born population, followed by Italian at 10.2%, Yiddish at 7.9%, Polish at 7.1%, and Swedish at 5.1%. No other language exceeded 4%. In contrast, the American Community Survey (ACS) recorded some 382 languages spoken in the United States, which for purposes of presentation were coded into 39 languages and language groups, the largest of which are summarized in Table 3. Here we draw on merged ACS files for 2008-2010 to achieve greater reliability in estimating data for languages spoken by few people, yielding samples and estimates that pertain roughly to 2009.

Table 3. Main languages spoken in the United States and nativity of speakers, 2008-10.

| (population 5 years or older) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Languages spoken | Estimated N of speakers | % of population | % speakers foreign-born | % speakers born in U.S. |

| English-only | 228,285,377 | 79.7 | 2.6% | 97.4% |

| Non-English languages | 58,266,345 | 20.3 | 56.7% | 43.3% |

| Europe/Americas: | ||||

| Spanish | 36,149,240 | 12.6 | 49.4% | 50.6% |

| French* | 1,267,188 | 0.4 | 38.6% | 61.4% |

| German* | 1,102,804 | 0.4 | 38.6% | 61.4% |

| Russian | 849,796 | 0.3 | 82.6% | 17.4% |

| Italian | 738,871 | 0.3 | 40.6% | 59.4% |

| Haitian Creole | 696,163 | 0.2 | 71.5% | 28.5% |

| Portuguese | 689,697 | 0.2 | 70.5% | 29.5% |

| Polish | 583,427 | 0.2 | 66.7% | 33.3% |

| Greek | 313,092 | 0.1 | 42.1% | 57.9% |

| East/South Asia: | ||||

| Chinese | 2,633,123 | 0.9 | 78.0% | 22.0% |

| Hindi, Urdu and related | 2,088,057 | 0.7 | 81.4% | 18.6% |

| Filipino Tagalog and related | 1,709,651 | 0.6 | 87.1% | 12.9% |

| Vietnamese | 1,338,309 | 0.5 | 76.7% | 23.3% |

| Korean | 1,124,994 | 0.4 | 80.7% | 19.3% |

| Khmer, Hmong, Lao and related | 748,896 | 0.3 | 65.7% | 34.3% |

| Dravidian | 595,019 | 0.2 | 88.5% | 11.5% |

| Japanese | 455,253 | 0.2 | 60.4% | 39.6% |

| West Asia/North Africa: | ||||

| Arabic | 819,678 | 0.3 | 69.5% | 30.5% |

| Persian (Farsi) | 370,759 | 0.1 | 79.5% | 20.5% |

| All other languages | 3,992,328 | 1.4 | 61.3% | 38.7% |

| Total (5 years or older) | 286,551,722 | 100% | 13.6% | 86.4% |

French excludes Patois, Cajun, Haitian Creole; German excludes Pennsylvania Dutch. Source: American Community Survey (ACS), 2008-2010 merged files.

The first two columns of the table show the estimated number and percentage of people aged 5 and above who reported speaking various languages at home (though for non-English speakers we have no data on their fluency in or frequency of use of that language). As already noted, Spanish overwhelmingly dominates among non-English languages spoken in the United States. In all, 12.6% of U.S. residents aged five or above said they spoke Spanish at home. The next closest language was Chinese, accounting for just 0.9% the population, followed by Hindi, Urdu and related languages at 0.7%, Tagalog and related Filipino languages at 0.6%, and Vietnamese at 0.5%. No other language category exceeded 0.5%. Moreover, the two largest non-English categories after Spanish themselves hide considerable diversity, given the many mutually unintelligible dialects of Chinese and the diversity of tongues spoken by people from the Indian subcontinent.

The right-hand columns show the percentage of language speakers born abroad and in the United States. Among those speaking Asian languages, the vast majority were born abroad, with two exceptions—those who speak Khmer, Hmong, Lao and related languages, 34.3% of whom were native born, and those who speak Japanese, 39.6% of whom were native born. The former figure reflects very high levels of fertility and declining immigration after 1990 for groups from Laos and Cambodia, whereas the latter reflects the high levels of education exhibited by the Japanese, who are also the only Asian-origin population that is primarily U.S.-born. The share of speakers born in the United States does not exceed 25% for any other Asian language. Speakers of Arabic and Farsi are likewise dominated by immigrants, with just 30.5% of the former and 20.5% of the latter being native born.

Among languages spoken in Europe and the Americas, percentages of immigrant versus native speakers are quite variable. At one extreme are speakers of Russian, Creole, Portuguese, and Polish, with respective native percentages of 17.4%, 28.5%, 29.5%, and 33.3%. At the other extreme are speakers of French, German, Italian, and Greek, with respective native percentages of 61.4%, 61.4%, 49.4%, and 57.9%. Spanish speakers lie in-between these two extremes, with roughly half being born in the U.S. and half abroad.

The Future of Language Diversity

Speaking a foreign tongue at home does not necessarily imply a lack of fluency in English, of course; but if the past is any guide to the future, the prospects for stable bilingualism in the United States are slim given the nation's well established reputation as a graveyard for immigrant languages. As in past censuses, the ACS does not ask Americans how well they speak a non-English language; instead, those who report that they speak a non-English language at home are asked how well they speak English. (Those who did not answer the question are assumed to speak English only.) Among the nearly 60 million people who speak a foreign language at home, Table 4 takes up the issue of their English language proficiency by showing the percentage who reported speaking English only or very well, and the percentage speaking it not well or not at all. We show percentages for non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and major ethnic groups of Latin American and Asian origins, along with the percentage foreign born in each group. Once again we pooled the 2008-2010 waves of the American Community Survey to derive more reliable estimates.

Table 4. Size, immigrant share, and English proficiency of U.S. ethnic groups, 2008-10.

| Ethnic/pan-ethnic groups | N | % of U.S. population | % foreign- born | Speaks English*… | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| only | very well | not well or at all | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 199,925,233 | 65.2 | 3.8% | 94.2% | 4.1% | 0.7% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 39,405,797 | 12.8 | 7.7% | 93.1% | 4.6% | 0.9% |

| Latin American origins: | ||||||

| Mexican | 32,054,091 | 10.4 | 36.2% | 24.3% | 38.8% | 22.9% |

| Puerto Rican (in mainland) | 4,562,169 | 1.5 | 1.1% | 34.9% | 46.5% | 8.3% |

| Cuban | 1,760,256 | 0.6 | 58.9% | 17.6% | 41.4% | 27.2% |

| Dominican | 1,421,609 | 0.5 | 57.1% | 8.8% | 45.6% | 28.8% |

| Salvadoran, Guatemalan | 2,811,922 | 0.9 | 65.5% | 8.7% | 34.3% | 37.7% |

| Colombian | 943,989 | 0.3 | 65.8% | 13.4% | 45.3% | 20.2% |

| Peruvian, Ecuadorian | 1,201,984 | 0.4 | 66.7% | 11.3% | 41.9% | 25.6% |

| Other Central/South American | 2,169,199 | 0.7 | 64.5% | 15.9% | 42.8% | 23.4% |

| Asian origins: | ||||||

| Chinese | 3,369,879 | 1.1 | 69.0% | 18.0% | 36.4% | 23.8% |

| Asian Indian | 2,831,277 | 0.9 | 72.6% | 20.3% | 57.7% | 7.3% |

| Filipino | 2,590,676 | 0.8 | 66.0% | 32.9% | 45.0% | 5.2% |

| Vietnamese | 1,601,842 | 0.5 | 68.0% | 12.1% | 34.8% | 28.9% |

| Korean | 1,492,080 | 0.5 | 74.1% | 21.8% | 32.8% | 22.5% |

| Japanese | 816,299 | 0.3 | 40.2% | 55.6% | 20.7% | 9.0% |

| Cambodian/Hmong/Laotian | 734,354 | 0.2 | 54.3% | 14.7% | 43.0% | 22.1% |

| Other Asian | 1,227,546 | 0.4 | 59.1% | 27.4% | 41.6% | 11.5% |

| All other ethnic groups | 5,818,232 | 1.9 | 12.2% | 65.3% | 25.4% | 3.7% |

| Total population | 306,738,434 | 100.0 | 12.8% | 79.7% | 11.6% | 4.7% |

Asked of those speaking a language other than English at home (ages 5 and older).

Source: American Community Survey (ACS), 2008-2010 merged files.

As one might expect, the overwhelming majority of non-Hispanic whites and blacks (93%-94%) speak English only, with almost all of the small remainder speaking it very well (4%-5%). In sharp contrast, as shown in the column on the percentage foreign born, while well over 90% of non-Hispanic whites and blacks are natives, most Latin American and Asian groups are heavily dominated by immigrants. The principal exceptions among Hispanics are Mexicans (just 36.2% foreign born) and Puerto Ricans (almost all of whom are U.S. citizens by birth, though many are island born). Among other Latin American groups the percent foreign born ranges from 57% to 67%. Even more than Latin Americans, Asians tend to be dominated by immigrants, with the sole exception of the Japanese, among whom only 40.2% were born abroad. Among those of other Asian origins, the share born abroad ranges from 54% to 74%.

Groups with lower shares of foreigners generally exhibit higher rates of mother tongue extinction, with 55.6% of Japanese speaking English only, compared with figures of 34.9% among Puerto Ricans and 24.3% among Mexicans. Despite their concentration in areas where Spanish is widely spoken, therefore, roughly a third of Puerto Ricans and a fourth of Mexican Americans have made the transition to monolingual English. Apart from these national origins, few Latin American groups have made the shift to English only, with the share ranging from around 9% among Dominicans, Salvadorans, and Guatemalans (groups with lower levels of education), to 16% among those in the residual “other Latin American” category, and 17.6% among the Cubans (who have been in the U.S. longer than other Latin American groups except the Mexicans and Puerto Ricans).

A relatively high percentage of Filipinos (32.9%) also speak English only, despite the fact that two-thirds of them are foreign born. The Philippines, of course, are a former American colony where English is widely taught and commonly spoken by the educated. Compared with Latin Americans, the share of Asians speaking only English is somewhat higher but always well below a third of the population, except for Filipinos and the Japanese. Among other Asian groups, the percentage speaking English only ranges from 12% among the Vietnamese to 27% in the residual “other Asian” category.

Those Latin Americans and Asians who report speaking English very well must be at least somewhat bilingual since they speak another language at home (though we cannot determine how well from the official statistics). Bilingualism defined in this rough way is most common among Asian Indians (57.5%) but is also relatively common among Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans, Colombians, Peruvians, and other Central or South Americans, for each of whom the percentage speaking English very well ranged from 41% to 47%. Filipinos, Laotians, Cambodians and other Asians also display “bilingual” rates in the same range.

Despite a preponderance of immigrant origins in most of these groups, the percentage who speak no or limited English is fairly low—under 30% for all groups except Salvadorans and Guatemalans, many of whom have indigenous mother tongues, lower levels of education, and are more recently arrived with undocumented statuses. In some groups—Puerto Ricans, Asian Indians, Filipinos, and the Japanese—the share speaking little or no English is under 10%. Taking those who speak English only and very well together roughly indicates the degree of English language fluency and by this criterion a majority of all groups are fluent in English, again with the exception of Salvadorans and Guatemalans, and the Vietnamese. Among other groups the share speaking English only or very well ranges from 53% among Peruvians and Ecuadorans to 81% among Puerto Ricans. In general, Latin Americans are just as likely to speak English proficiently as Asians, which is consistent with recent survey data suggesting that huge majorities of Hispanics view learning English as “very important,” even recently arrived non-citizens.8

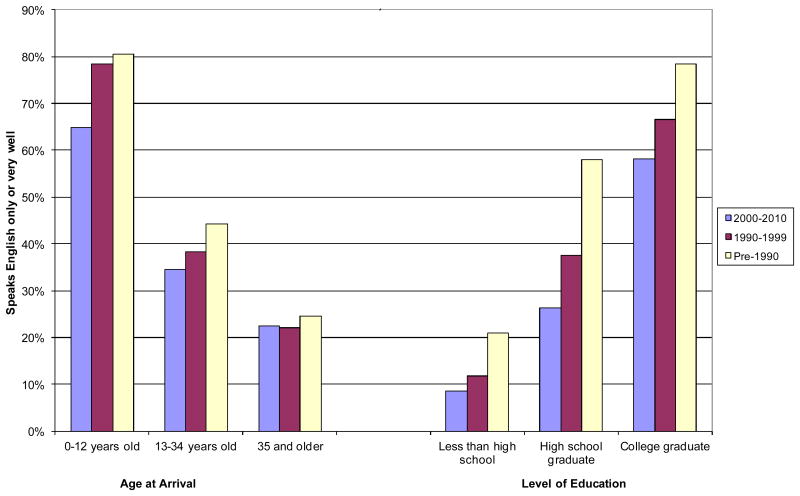

Three key determinants of English language fluency among the foreign born (from non-English speaking countries) are age at arrival, years of education, and time in the United States. It is much easier for human beings to learn languages prior to adolescence, and education generally increases exposure to English as well as cognitive skills. Period of arrival, of course, determines the length of direct exposure to an English language-based culture and society. Figure 1, based on 2010 ACS data for immigrants from non-English-speaking countries, shows how the share speaking English only or very well varies according to these three background factors. The bars to the left reveal that English proficiency is very high among those who arrived before the age of 13. Among those who arrived before this age, 81% speak English only or very well if they came before 1990 (yielding at least 30 years of exposure to American English), 78% do so if they came between 1990 and 2000 (at least 20 years), and 65% do so even if they arrived between 2000 and 2010 (ten or fewer years). Among those who arrived between the ages of 13 to 39, their respective levels of English proficiency plummet to 34%, 38%, and 44%, and among those who arrived at age 35 or later the share falls to between 22% and 25% with little variation by year of arrival. Thus arrival before adolescence is critical to achieving English fluency.

Figure 1. English Proficiency of Immigrants by Age at Arrival, Education, and Decade of Arrival, 2010.

The right-hand bars show the powerful effect of education on English proficiency, as those with less than a high school education are quite unlikely to speak English very well, especially if they arrived after 2000 (just 8% spoke English only or very well) or between 1990 and 2000 (only 12%); but the prospects of English proficiency do not rise much even for those who arrived prior to 1990 (just 21% spoke it well or only). In contrast, among high school graduates who arrived before 1990, 58% speak English only or very well, though among those who arrived between 1990 and 2000 the percentage is lower at 38% and lower still at 26% for those who arrived after 2000.

Very obviously, a college education greatly increases the prospects of English proficiency. Even among those who arrived most recently (after 2000), 58% spoke English only or very well, and the share rises to 67% among those arrived between 1990 and 2000, and to 79% among those who came before 1990. Thus the prospects for speaking English fluency are very bright for those who are well educated, arrived before adolescence, and (especially if they are young and better educated) who have lived in the U.S. for more at least a decade. The data presented back in Table 4 hint at the possibility that immigrants today may be following the path of their predecessors toward native language decline and English dominance and proceed over time to the extinction of their mother tongues. As we noted, more than a third of Puerto Ricans and nearly a quarter of Mexicans spoke only English in 2010. Without more precise knowledge of the generational composition of the various populations, however, it is difficult to assess the likelihood of linguistic survival over time.

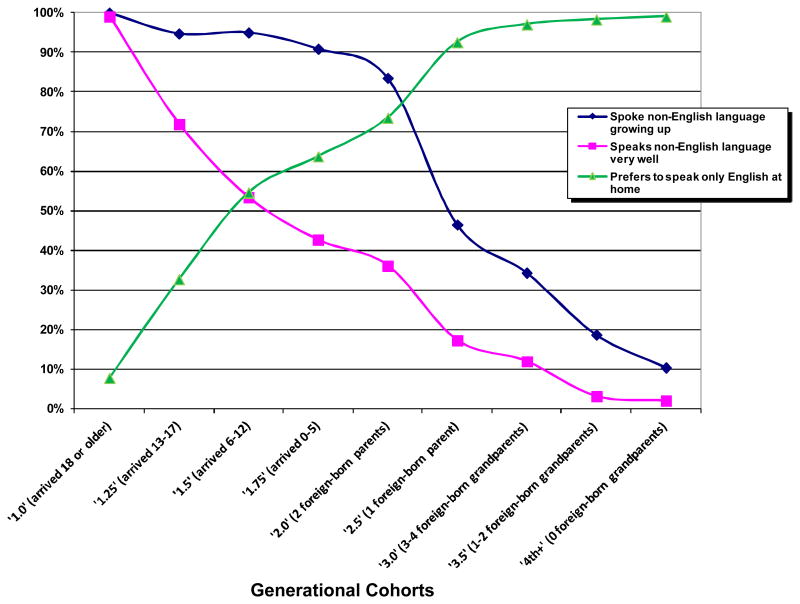

Figure 2 draws follows an approach developed by Rumbaut et al. who combined data from the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study in San Diego and the Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles study to estimate linguistic “survival curves” across detailed generational groups in Southern California, which owing to mass immigration has high densities of non-English speakers, especially Spanish speakers.9 Indeed, the 2010 ACS found that of the 21 million residents in the six counties of Southern California, half spoke English only and half reported speaking a non-English language at home. Generally, we define the first generation as immigrants born outside the United States; the second generation as those born in the United States of immigrant parents; the third generation as those born in the United States to native-born parents and one or more immigrant grandparents; and the fourth generation as natives with native-born parents and grandparents. The detailed data available from the above surveys enable us to break these broad generational groups down into fractional cohorts corresponding to different levels of exposure to the English language environment of the United States and different degrees of separation from the mother tongue and from the experience of being socialized in immigrant families at key developmental ages.

Figure 2. Non-English Language Use, Proficiency, and Preference, by Generational Cohort.

Specifically, we divide the first generation into four distinct cohorts by age at arrival. Those who arrived as adults 18 or older constitute the 1.0 generation; those who arrived as adolescents between the secondary-school ages of 13 and 17 are the 1.25 generation; those arriving between the primary-school ages of 6 and 12 are the 1.5 generation; and those arriving from infancy to age five are the 1.75 generation, closer in their developmental experience to second-generation peers. We also divide the second generation into two groups: those in the 2.0 generational cohort have two foreign-born parents, whereas those in the 2.5 generation have one foreign-born and one native-born parent. The third generation is similarly divided into a 3.0 cohort with 3 or 4 foreign-born grandparents, and a 3.5 cohort with just 1 or 2 immigrant grandparents. Finally, those in the fourth generation are the farthest removed from the immigrant experience, with both native parents and no foreign-born grandparents.

Figure 2 summarizes the cross-generational story of non-English language use, proficiency and preference. It clearly shows that as one proceeds upward through the these fractional generations, the percentage speaking a non-English language while growing up drops, as does the percentage able to speak a non-English language well; but the percentage who prefer to speak only English at home rises rapidly. Speaking a non-English language while growing up persists at high levels through the 2.0 generation and then plummets with the addition of one native-born parent in the 2.5 generation. While exposure to a non-English language while growing up may remain high into the second generation, however, this does not translate automatically into either foreign language fluency, literacy or use. Although 84% percent of those in the 2.0 generation spoke a non-English language while growing up, only 36% said they spoke it well at the time of the survey and 73% said they preferred to speak English at home. Moreover, although it is not shown in Figure 2, their levels of non-English language literacy (reading and writing ability) dropped even more rapidly than their ability to understand or speak that foreign language. The loss of non-English literacy, in turn, is typically a prelude to the loss of the mother tongue altogether.

Thus proficiency and use of non-English languages barely survive into the second generation even in places of immigrant concentration such as Los Angeles and San Diego, with their high densities of non-English speakers. By the 2.5 generation the percentage speaking a foreign language well drops to 17%, and the share preferring to speak English at home rises to 93%. In the 3.0 generation these percentages become 12% and 97%. By the fourth generation the share speaking a foreign language well drops to 2% and the share preferring English at home is 99%. When Spanish speakers are broken out and considered separately from other non-English languages, the percentage speaking their mother tongue well is slower to fall and the share preferring English at home is slower to rise in the second generation, but by the third and fourth generations the curves end up at the same point, no matter which group one considers.10

Conclusion

The foregoing analysis provides no support for those arguing that mass immigration will produce a fragmented and balkanized linguistic geography in the United States. The revival of immigration has simply restored language diversity to something approaching the country's historical status quo, at least as measured by the variety of non-English languages and the number of non-English speakers; but in the absence of continued large-scale immigration, and even with its comtinuation at moderate levels, our data suggest that the mother tongues of today's immigrants will persist somewhat into the second generation but then fade to a vestige in the third generation and expire by the fourth, just as happened to the mother tongues of the Southern and Eastern European immigrants who arrived between 1880 and 1930 and their descendants. Even the fact that a much larger fraction of immigrants today speak a single language, Spanish, does not seem to alter the ultimate trajectory of linguistic survival. Indeed, even in Southern California, the nation's premier immigrant megalopolis where non-Hispanic whites are no longer the majority, the density of a wide range of Asian languages is presently quite high and that of Spanish speakers is higher still, it appears that proficiency in and use of Spanish effectively die out in the third generation and disappear into the nation's language graveyard in the fourth. The loss of Asian language fluency and use takes place faster still.

Whether Spanish and other immigrant languages persist in being spoken within the United States depends mainly on future trends in immigration, on whether they bring in enough first-generation language speakers to offset the rising tide of linguistic deaths in the 2.5 generation and above, and perhaps, if current trends were reversed, on whether fluent bilingualism might come to be valued rather than eschewed in the larger economy and society. With respect to Spanish speakers, immigration from Latin America continues but the boom in Mexican immigration appears to be over, at least for the moment. Mexicans presently constitute around 62% of all undocumented residents of the United States, 55% of all Latin American immigrants in the country, and 29% of all immigrants taken together.11 In a very real way, Mexico was the tail wagging the dog of Spanish language immigration to the United States in recent decades. No other country comes even close to matching Mexico's dominance.

Recent work by Jeffrey Passel and colleagues at the Pew Hispanic Center suggests that net migration from Mexico has likely fallen to zero and may even be negative.12 Whether or not Mexican migration eventually resumes remains to be seen, but the era of mass undocumented migration which contributed so much to Latin American population growth in the United States is probably over. Labor demand in the United States remains weak and what demand exists is now being met by legal temporary workers, as Congress has quietly opened the door to mass temporary worker migration from Mexico to levels not seen since the heyday of the Bracero Program in the late 1950s, providing new opportunities for legal circulation back and forth rather than settlement. Within Mexico the economy is growing, labor force growth is decelerating, fertility is declining, education levels are rising, and wages are holding steady in the face of stagnating earnings in the United States, making the U.S. far less attractive as a destination.

If mass immigration does not resume in the near future we may witness the same process of mother tongue extinction among Mexicans as occurred among earlier generations of European migrants. Indeed, given the power of popular American culture and the dividends to be gained from English fluency, it turns out to be quite difficult to maintain stable bilingualism in the United States. Whether this is a good or a bad thing depends on one's point of view. On the one hand it assures the continuation of a common civic language in the United States. On the other hand, there is little evidence that fluency in multiple languages damages the integration and cohesiveness of U.S. society; on the contrary, in a very real way the progressive death of immigrant tongues represents a costly loss of valuable human, social and cultural capital, for in a global economy speaking multiple languages is a valuable skill. Certainly the economy of the Americas would function more fluidly and transparently if more people spoke at least two of the Hemisphere's three largest languages: English, Spanish, and Portuguese. A recent report by the Council of Europe makes the case for being plurilingual as an advantage in the future.13 Perhaps it is better to consider immigrant languages as a multidimensional resource to be preserved and cultivated rather than a threat to national cohesion and identity.

Contributor Information

Rubén G. Rumbaut, Email: rrumbaut@uci.edu, School of Social Sciences, 3151 Social Science Plaza, University of California, Irvine, Mail Code: 5100, Irvine, CA 92697, 949-824-2495.

Douglas S. Massey, Email: dmassey@princeton.edu, Office of Population Research, Wallace Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, 609 258 4949.

Notes

- 1.Shell Marc. Babel in America; or, the Politics of Language Diversity in the United States. Critical Inquiry. 1993;20:103–127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber David J. The Spanish Frontier in North America. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1992. See: [Google Scholar]; Fleming Thomas. The Louisiana Purchase. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]; Gómez Laura E. Manifest Destinies: The Making of the Mexican American Race. New York: New York University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massey Douglas S. The New Immigration and the Meaning of Ethnicity in the United States. Population and Development Review. 1995;21:631–52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson Campbell, Jung Kay. Population Division Working Paper No 81. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2006. Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rumbaut Rubén G. A Language Graveyard? The Evolution of Language Competencies, Preferences and Use Among Young Adult Children of Immigrants. In: Wiley Terrence G, Lee Jin Sook, Rumberger Russell., editors. The Education of Language Minority Immigrants in the United States Bristol. UK: Multilingual Matters; 2009. pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford James. Seven Hypotheses on Language Loss: Causes and Cures. In: Cantoni Gina., editor. Stabilizing Indigenous Languages. Flagstaff: Northern Arizona University; 2003. pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veltman Calvin. Language Shift in the United States. New York: Walter De Gruyter; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowling Julie A, Ellison Christopher G, Leal David L. Who Doesn't Value English? Debunking Myths About Mexican Immigrants' Attitudes Toward the English Language. Social Science Quarterly. 2012;93(2):356–378. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rumbaut Rubén, Massey Douglas S, Bean Frank D. Linguistic Life Expectancies: Immigrant Language Retention in Southern California. Population and Development Review. 2006;32:447–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibid.

- 11.Acosta Yesenia D, de la Cruz G Patricia. The Foreign Born From Latin America and the Caribbean: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passel Jeffrey, Cohn D'Vera, González-Barrera Ana. Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero—and Perhaps Less. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skutnabb-Kangas Tove. Why Should Linguistic Diversity Be Maintained and Supported in Europe? Some Arguments. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 2002. [Google Scholar]