Abstract

Clinical trials in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) show variability in behavioral responses to the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine (ATX). The objective of this study was to determine whether Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)-evoked Short Interval Cortical Inhibition (SICI) might be a biomarker predicting, or correlating with, clinical ATX response. At baseline and after 4 weeks of ATX treatment in 7–12 year old children with ADHD, TMS-SICI was measured, blinded to clinical improvement. Primary analysis was by multivariate ANCOVA. Baseline SICI did not predict clinical responses. However, paradoxically, after 4 weeks of ATX, mean SICI was reduced 31.9% in responders and increased 6.1% in non-responders (ANCOVA t41=2.88; p = .0063). Percent reductions in SICI correlated with reductions in ADHD-Rating Scale (ADHDRS) (r = .50; p = .0005). In children ages 7–12 years with ADHD treated with ATX, improvements in clinical symptoms are correlated with reductions in motor cortex SICI.

Keywords: Clinical Pharmacology / Clinical Trials, Psychopharmacology, Neuropharmacology, Biological Psychiatry, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, Atomoxetine, Short Interval Cortical Inhibition

INTRODUCTION

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a highly prevalent neurobehavioral disorder,1 is diagnosed empirically, based on major domains of impairment in attention, impulse control, and physical hyperactivity. Underlying neurophysiological mechanisms have been inferred primarily from correlative studies and may involve a variety of perturbations in the functional connectivity of neural networks contributing to cognition, motor control, and behavior.2 Current ADHD pharmacotherapy emphasizes modulation of catecholamines with stimulant and non-stimulant medications, prescribed through a trial and error process with no quantitative, biologically-based guidance. Atomoxetine (ATX) is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of ADHD 3 which typically takes four weeks or more to achieve a clinical reduction in ADHD symptoms. Although a large fraction of children may respond reasonably well to either stimulants or ATX, some children respond better to one, and others do not respond to either.4 This suggests two (or more) distinct underlying physiological characteristics predisposing children to respond preferentially to ATX.5 The objective of this study was to determine whether mechanisms linked to ATX response may be easily and inexpensively identified in motor cortex using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS).

TMS has been used to evaluate motor cortex physiological biomarkers of both the diagnosis and treatment-induced changes in ADHD.6–10 Rationales for this approach include commonly observed impairments in fine motor control in ADHD,11 and neuroimaging findings in the frontal cortex and motor control systems.12 TMS pulses non-invasively activate populations of neurons of the underlying cerebral cortex, producing local evoked potentials. Stimulating over hand motor cortex produces motor evoked potentials (MEPs), easily measurable by surface electromyogram (EMG) in hand muscles, with amplitudes that reflect the local balance of inhibition and excitation. Paired-pulse TMS protocols are widely used to activate excitatory or inhibitory neuronal populations in order to evaluate disorders involving synaptic transmission as well as to understand and quantify pharmacological effects.13,14 Paired subthreshold (conditioning)/suprathreshold (test) TMS pulses delivered at an interstimulus interval of 3 msec activate the GABAA-mediated cortical inhibitory interneurons. This phenomenon is used to measure short interval cortical inhibition (SICI).15 SICI appears to be altered in a number of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

Previous studies have found significantly diminished SICI in the dominant motor cortex of children 6,10,16 and adults 17,18 with ADHD. Further, greater reductions in SICI are found in children with more severe ADHD, particularly hyperactivity symptoms.10,19,20 As would be expected, several studies have found that a single dose of the stimulant methylphenidate increases (“normalizes”) SICI. 6,8,16 In a small prior study, we found that ATX treatment in ADHD might exert, paradoxically, the opposite effect and reduce SICI.21

The aim of our current study was to determine in a larger study of children with ADHD whether TMS-SICI changes, assessed blinded to clinical improvement, would be a biomarker of ATX response. Further, if ATX reduces SICI, opposing previously published studies showing stimulants increase SICI, the results of the present study would provide a foundation for future investigations to determine whether TMS-SICI might differentiate distinct mechanisms of ADHD treatment responses or distinguish treatment-responsive ADHD subgroups.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects

Children with ADHD aged 7 to 12 years were recruited through clinic referrals and from community advertisement. Typically subjects and their guardians were either seeking their first medication treatment for ADHD or were specifically seeking atomoxetine (ATX). Participants previously treated with stimulants were eligible, but subjects adequately maintained on any effective ADHD medication regimen were excluded.

The rationale for recruitment was to study a clinically relevant, generalizable population of children who would present to a clinician seeking ADHD treatment with atomoxetine. Eligibility requirements included a diagnosis of either combined or inattentive type ADHD as determined by a structured interview with the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL).22 Both predominantly inattentive and combined type ADHD were allowed in order to increase generalizability, with the plan to statistically evaluate subtypes and symptom severity subscores. Severity of ADHD symptom burden was confirmed by an ADHD Rating Scale (ADHDRS) (35) score of at least 1.5 SD higher than age/gender means by ADHD subtype. Further confirmation of symptom spectrum was obtained thru Swanson, Nolan and Pelham (SNAP)-IV-Parent 23 ratings. Clinical ratings of anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS).24 Cognitive ability was screened using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (WASI).25 Children with estimated full scale IQ of < 75 were excluded. Comorbidity was allowed but ADHD must have been the primary diagnosis and focus of treatment. Study participants underwent comprehensive health history, review of systems, physical examination, laboratory measures including complete blood count, basic chemistries with liver panel, thyroid function test, urinalysis, pregnancy test (if relevant), and electrocardiogram (ECG). Any child that had a medical condition requiring pharmacological treatment that would interact with ATX or in which ATX would be contraindicated was excluded.

Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from parents/guardians with assent obtained from child subjects. The study was conducted jointly in the department of psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati and the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and approved by the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) Institutional Review Boards.

Atomoxetine treatment protocol

Study duration was 6-weeks involving 7 total visits, one per week, the first two of which were for baseline assessments collected off medication to determine consistency of ADHD scores. After completion of study baseline, participants presented to the CCHMC TMS laboratory for TMS and stop signal reaction time studies (TMS 1). The TMS team was blinded to ADHD severity scores. On the day after TMS1, participants began daily treatment with open-label administration of ATX starting at 0.5 mg/kg. Participants returned to the outpatient psychiatry clinic weekly where the primary investigator (FRS), blinded to TMS results, evaluated participants for ADHD symptom severity (ADHDRS, Clinical Global Impression – Severity Scale [CGI-S]), Clinical Global Impression of Improvement (CGI-I), vital signs, adverse events, and compliance (pill counts). ATX dosing was titrated weekly using available formulations (as recommended in the manufacturer’s label), up to approximately 1.2 mg/kg/day or 60 mg daily, whichever was lower. The maximum dose was maintained for the final week. After 4 weeks of ATX treatment a final assessment of clinical response was made, vitals, adverse events, medication compliance, psychiatric symptoms, and final ADHD ratings were obtained. Participants then returned to the TMS lab at CCHMC for repeat TMS studies and stop signal reaction time studies, blinded to clinical response status.

Categorical and Dimensional Assessment of Responder Status

The primary categorical outcome was the 4-week-treatment responder status as rated by a trained child psychiatrist (FRS), blind to TMS outcomes. Responses were stratified as a dichotomous variable (Responder, non-Responder) based on two 7-point Clinical Global Impression Scales (CGI) for improvement (CGI-I) and severity (CGI-S).26 Responders at endpoint had to have both CGI-S of 1 (normal) or 2 (borderline ill) and CGI-I of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved). All others were designated non-responders. The secondary, dimensional outcome was the investigator-administered and scored DuPaul ADHD Rating Scale-IV (ADHDRS-IV).27 This includes the Inattention (A) and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity (H) subscales, each consisting of 9 items scored 0 (never or rarely) to 3 (very often), with a maximum total score of 54. Dimensional clinical improvement was evaluated as a percent change in the ADHDRS from baseline to 4 weeks.

TMS Studies

All TMS studies were performed in the TMS Laboratory at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center using two Magstim 200® stimulators (www.magstim.com) connected through a Bistim® module to a double 70 mm figure 8 coil. Methodology has been previously published and described in detail.10 In brief, motor-evoked potentials were measured at the first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle of the dominant hand with Ag/Cl surface EMG electrodes, amplified, and filtered (100/1000 Hz) (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA). Motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes were recorded and stored using Signal® software and a Micro1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Resting Motor Threshold (RMT) was the lowest intensity that would produce MEP amplitudes of at least 50 uV on 3 out of 6 consecutive stimulation trials. Active Motor Threshold (AMT) was the lowest intensity was reached that produced MEPs larger than background in 3 out of 6 trials while abducting the first finger against a ball. The Cortical Silent Period (CSP) was evaluated with 5 pulses administered at 1.5*AMT during FDI activation.

Paired-pulse (PP) TMS was used to evaluate short interval cortical inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF) at rest. Each paired pulse trial consisted of a subthreshold conditioning stimulus (CS, at 60% of RMT) followed by a suprathreshold test pulse (TP, at 110–130% RMT) at an interstimulus interval (ISI) of either 3 ms (inhibition – SICI) or 10 ms (facilitation – ICF). Thirty total trials consisting of 10 single pulse (SP) TMS, 10 3-msec PP TMS, and 10 10-msec PP TMS were delivered in a random order, separated by 6 ± 10% seconds. For PP TMS, a ratio < 1 indicates inhibition and >1 indicates facilitation. The conditioning pulse intensity and interstimulus intervals were chosen based on robust results in prior ADHD studies.10,28,29 Tracings with any artifact 200 msec prior to and 20 msec after the TMS pulse were removed. Methods for reducing unwanted movement and motion artifact have been described previously.10

Behavioral Inhibition: Stop Task Paradigm

The stop task paradigm, designed for use with Presentation® software (www.neurobs.com), consisted of trials with either: 1) the primary “Go” instruction only – a choice reaction time test in which participants are instructed to press either “X” or “O” buttons on a game controller as quickly as possible in response to visual cue; or 2) the secondary “Stop” task – a response inhibition test in which participants are instructed to withhold pressing a button when, following the “X” or “O” visual Go cue, they hear a Stop tone.30 After one practice block, there were four blocks that consisted of 24 trials: 18 Go and 6 Stop. Each trial consisted of 500 msec of a fixation point, followed by a 1000 msec Go task (X or O, without or with a stop tone), followed by a blank screen for 2000 msec. Auditory stop signal timing was delivered 50 msec later after a successful stop trial, making inhibition more difficult, and 50 msec earlier after failure, making inhibition easier. Thus, the Stop signal latency automatically adjusted to result in a 50% success rate. This allowed for an estimated Stop Signal Reaction Time (SSRT) as the difference between the mean choice reaction time (MCRT) and the mean stop signal delay.

Statistical Analysis and evaluation for potential confounders

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (www.SAS.com). Primary analysis to determine whether mean motor cortex inhibition (SICI) changes differed in ATX responders versus non-responders employed analysis of covariance. The primary dependent variable was 4-week SICI. The primary predictor was ATX response status. Baseline SICI and age were planned covariates. Because ADHD subtype and ADHDRS scores differed in the response groups (see results, table 1), these were evaluated as possible confounders. First, ADHD subtype and baseline ADHDRS were added to the model and tested as interaction terms with treatment response category. The interactions were not significant. Second, the ADHD subtype and ADHDRS were added individually to the primary ANCOVA to test for significance and found to be far from significant (ADHDRS p = 0.78; ADHD Type p = 0.84). As there was no significant degree of interaction among the covariates, a main-effects model could be applied. Adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. ICF and SSRT changes were similarly analyzed.

Table 1.

Baseline (Pre-Treatment) Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Atx Responders n=52 | Atx Non Responders n=43 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | NS | ||

| Male | 32 (62) | 31 (72) | |

| Female | 20 (38) | 12 (28) | |

| Race | NS | ||

| White | 34 (65) | 29 (67) | |

| African American | 13 (25) | 13 (30) | |

| Mixed | 5 (10) | 1 (2) | |

| Previous stimulant treatment | 28 (54) | 27 (63) | NS |

| ADHD subtype | .015 | ||

| Combined | 35 (67) | 38 (88) | |

| Inattentive | 17 (33) | 5 (12) | |

| mean (SD) | mean (SD) | ||

| Age, years | 10.1 (1.7) | 9.4 (1.7) | .049 |

| ADHDRS Total | 35.9 (8.7) | 41.0 (7.2) | .003 |

| Inattentive | 20.8 (4.3) | 22.1 (2.8) | .079 |

| Hyperactive/Impulsive | 15.1 (6.9) | 18.9 (5.4) | .004 |

Secondary dimensional analysis of the ADHD/SICI relationship was performed calculating the Pearson correlation of the baseline to 4 week percentage changes in ADHDRS and in SICI. ICF and SSRT correlations were similarly calculated.

Finally, exploratory analysis was performed to identify predictors of responder status. Simple t-tests were performed to evaluate responder group differences in baseline and 4-week ADHDRS, SSRT, SICI, ICF, RMT, AMT, and CSP.

A higher number of children than expected had high baseline RMTs. This resulted in no SICI being obtainable in a large number of participants. To clarify generalizability of the results of our main analysis, demographic and clinical features were compared between children whose SICI was obtainable versus those in whom it was not.

RESULTS

Demographics

The study sample was comprised of 108 children, including 95 children analyzed who had clinical data at study onset and after 4 weeks of treatment. Thirteen children were enrolled and not included either because they dropped out prior to the first-dose visit (6) or failed to follow up and violated study protocols after the first dose (7). Demographics of the analyzed sample were sex 63 males (66%), 32 females (34%); race 63 Caucasian (66%), 26 African American (27%), 6 mixed (6%); ethnicity 4 Hispanic (4%). Hand dominance was 79 right-handed (83%); 15 left-handed (16%), one mixed dominance.

Adverse Events

There were no serious adverse events recorded due to either ATX or due to participation in TMS studies. Other adverse events were mild and consistent with those reported in clinical trials of ATX.3,4

Clinical, Behavioral, and Physiological Assessments

Demographics and ADHD scores at baseline are shown in table 1. Clinical responses were obtained in all 95 subjects at baseline and 4 weeks. Stop Signal was attempted in all subjects but in 11 there was poor effort, the children did not understand the game, or the percent successful inhibition was below 35% so that the SSRT was considered invalid. TMS was attempted in all subjects. Active motor thresholds were attainable in 86 and resting motor thresholds in 78. In the remainder of cases the there was no elicitable RMT at 100% of stimulator intensity. If the single pulse TMS amplitudes were not consistently greater than 300 mV, then SICI, ICF were not obtainable or valid. SICI was obtained at both visits in 45 participants (47%).

Clinical Improvement

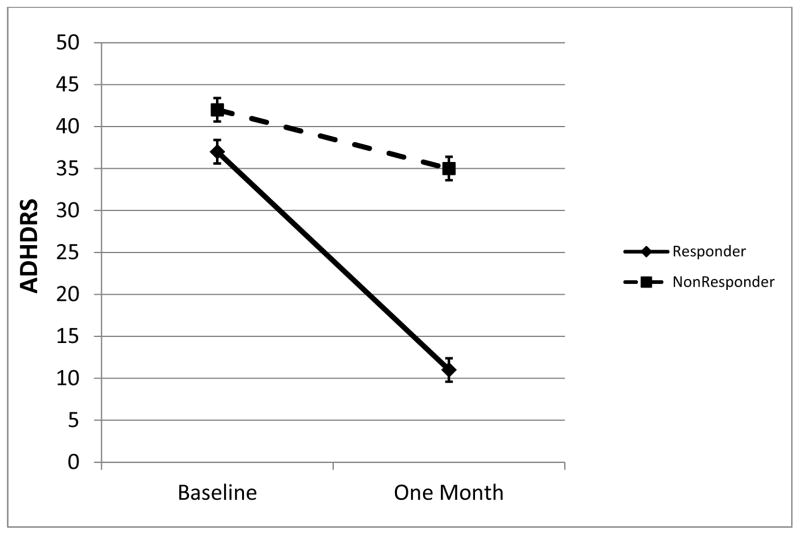

ADHDRS at baseline and after treatment are shown in figure 1. Fifty two (54%) met criteria as responders and the remaining 43 (46%) as non-responders. In the responder group, there was a mean 69% (25 point) reduction in ADHDRS. In the non-responder group, there was a mean 24% (10 point) reduction in ADHDRS. Most had previously tried stimulants (58%). Comparison of demographic and clinical ratings ADHDRS scores at baseline are found in Table 1. Non-responders were younger and had higher mean ADHDRS.

Figure 1.

ADHDRS in responders and non-responders at baseline and after 4 weeks of atomoxetine treatment. Means from ANCOVA, error bars are standard error.

Motor Cortex Inhibition and Excitation Changes stratified by Clinical Response to Atomoxetine

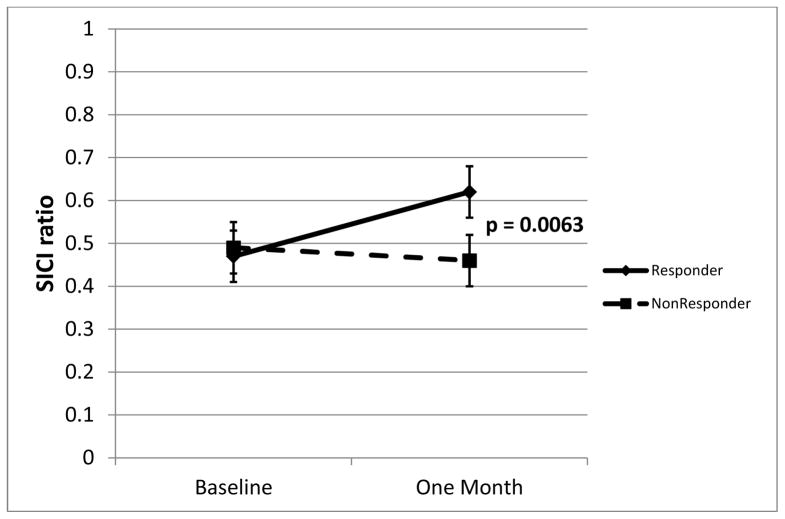

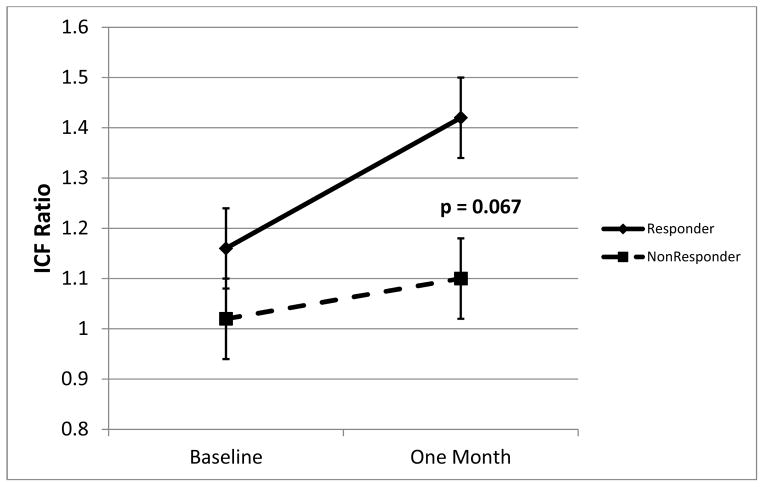

Mean (raw) SICI at baseline and after treatment is shown in figure 2. After 4 weeks of treatment, ATX responders had significantly less SICI (higher ratios, approaching 1.0, indicate less inhibition). Estimated mean post-treatment SICI in responders was 0.66 (SE .051), that is, 34% inhibition; in nonresponders SICI was 0.44 (SE 0.057), that is, 56% inhibition (ANCOVA t41=2.88; p = .0063). ICF at baseline and after treatment is shown in figure 3. After 4 weeks of treatment, ATX responders had, at the trend level, higher ICF. Estimated mean post-treatment ICF in responders was 1.40 (SE .095) (40% facilitation); in non-responders ICF was 1.13 (SE 0.11) (13% facilitation) (ANCOVA t41 = 1.88; p = .067).

Figure 2.

SICI in responders and non-responders at baseline and after 4 weeks of atomoxetine treatment. Means from ANCOVA, error bars are standard error.

Figure 3.

ICF in responders and non-responders at baseline and after 4 weeks of atomoxetine treatment. Means from ANCOVA, error bars are standard error.

Correlations between changes in ADHDRS and SICI, ICF and SSRT

Consistent with the primary categorical analysis, decreases in SICI correlated with decreases in ADHDRS total (r = 0.50; p = 0.0005), attention subscore (r = 0.42; p = 0.005) and hyperactivity/ impulsivity subscore (r = 0.44; p = 0.003).

There was no significant correlation between change in SSRT or change in ICF and change in ADHDRS.

Other TMS Measures

Baseline and post-treatment univariate treatment effects are shown in table 2. There were no significant differences in RMT, AMT, or CSP.

Table 2.

Baseline (Pre-Treatment) and 4-Week (Post-Treatment) Response Inhibition, & Motor Cortex Physiology

| BASELINE | 4 WEEKS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Atx Responders | Atx Non Responders | p value | Atx Responders | Atx Non responders | p value |

| Response Inhibition mean (SD) | ||||||

| Percent Correct | 92.1 (8.2) | 91.1 (10.4) | NS | 94.1 (6.8) | 92.7 (10.6) | NS |

| Percent Successful Inhibition | 54.4 (9.0) | 53.5 (14) | NS | 51.7 (8.2) | 52.5 (7.3) | NS |

| Choice Reaction Time (msec) | 669 (119) | 681 (146) | NS | 670 (143) | 697 (158) | NS |

| Standard Deviation Reaction Time (msec) | 183 (51) | 228 (101) | .008 | 190 (87) | 201 (85) | NS |

| Mean Delay (msec) | 281 (172) | 248 (206) | NS | 379 (161) | 404 (198) | NS |

| Standard Deviation Delay (msec) | 85 (26) | 93 (35) | NS | 72 (28) | 68 (18) | NS |

| Stop Signal Reaction Time (msec) | 386 (131) | 433 (179) | NS | 294 (120) | 294 (137) | NS |

| Motor Cortex Physiology mean (SD) | ||||||

| Resting Motor Threshold (% maximum) | 71.2 (18.6) | 67.8 (18.9) | NS | 67.1 (18.7) | 62.4 (16.0) | NS |

| Active Motor Threshold (% maximum) | 47.6 (12.8) | 48.8 (17.8) | NS | 43.5 (12.8) | 44.3 (13.9) | NS |

| Cortical Silent Period (msec) | 53 (35) | 60 (44) | NS | 56 (37) | 50 (30) | NS |

| Short Interval Cortical Inhibition (SICI ratio) | 0.50 (0.34) | 0.48 (.29) | NS | 0.63 (0.41) | 0.45 (0.35) | .10 |

| Intracortical Facilitation (ICF ratio) | 1.16 (0.61) | 1.02 (0.60) | NS | 1.41 (0.83) | 1.10 (0.61) | .03 |

Response Inhibition

Baseline and post-treatment response inhibition findings are shown in table 2. SSRT improved in both clinical responders and non-responders.

Assessments of children for whom SICI was not obtainable

Children for whom SICI was not obtainable were younger (mean 9.1 vs. 10.4 years; p < .001) and had higher RMT (mean 82 vs. 58; p < .001). However the proportion of responders was not different (54% vs. 55%) and baseline ADHDRS did not differ (mean 38.2 vs. 37.4; p = NS).

DISCUSSION

The primary finding of this study is that children with ADHD who respond clinically to atomoxetine (ATX) have a decrease in TMS-evoked short interval cortical inhibition (SICI). In contrast, after 4 weeks of ATX treatment, SICI did not change in non-responders. The dimensional analysis supported this finding: after ATX treatment, the percent of reduction in parent-rated ADHD symptoms correlated with the percent of reduction in SICI.

The objective of this study was to identify a biomarker correlating with treatment response to ATX. SICI was selected as a primary candidate based on case-control studies showing reduced SICI in ADHD and correlations between less SICI and greater ADHD symptom severity.7,10,16,20 Moreover, in prior studies, SICI did appear to be sensitive to single doses of psychostimulants and of norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors reboxetine and ATX.6,8,16,31 Most single dose studies have recruited small samples of healthy adults or children. Effects of single doses of medication on SICI have varied.31 Thus more research was needed to clarify whether SICI would be a consistent biomarker of treatment response in ADHD.

The direction of SICI change is paradoxical, in that the change correlating with clinical benefit is not in the direction of “normality.” Stimulant evoked increases in SICI have been found in prior single dose studies and suggest stimulants may normalize a deficiency in inhibition in some children with ADHD.6 Although at this time we can only speculate on the underlying neurobiology, there are few studies looking at more than single-dose responses. Moreover, our results are consistent with our prior, smaller study in children with Tourette Syndrome and ADHD, where one month of ATX treatment also reduced mean SICI, correlating with ADHD improvement.21 The consistent results of the present, larger study suggest that this seemingly paradoxical finding is a reproducible indicator of ATX treatment response in ADHD.

We designed this study to optimize our measure of interest, SICI, by selecting a conditioning pulse intensity to evoke moderate SICI while being lower than is optimal for facilitation. Another possible explanation for the apparent reduction in SICI would be an unexpected ATX effect on short interval facilitation (SICF). SICF is a paired pulse phenomenon elicitable at intervals which overlap with those of SICI 32,33 and thus it may contaminate SICI assessment. However, there are several reasons for interpreting this possibility cautiously. First, the optimal SICI and SICF pulse intensities are quite different. For SICF the first pulse is suprathreshold; whereas for SICI it is subthreshold. At the pulse intensities in our experiment, SICI effects should be much more robust than SICF ones, and therefore it seems unlikely that this excitation would dominate inhibition.29 Second, as recently shown, dopamine deficiency in Parkinson Disease is linked to increased SICF; and dopamine replacement in PD reduces SICF.34 So to the extent to which levodopa, stimulants, and ATX may all increase dopamine levels in cerebral cortex,35,36 it is not readily apparent why ATX would increase SICF in ADHD. Future studies evaluating both SICI and SICF, similar to those recently done in PD, may be helpful.

Significant potential limitations to this study include the open label design, subjective nature of parent rating scales of ADHD, and the fairly short, 4-week treatment period. In powering the study, we anticipated an approximate response rate at 4 weeks of 50%, which turned out to be fairly accurate. This 50–50 ratio would make it more difficult to have across-the-board positive expectancy about physiological changes. Moreover, TMS generates objective, quantitative measures and all experiments and analyses were performed blinded to treatment results. Thus while lack of blinding may have influenced parental perceptions, we do not think that this introduced much bias into our TMS findings. It would be surprising, for example, if the degree of “placebo response” to ATX correlated with degree of change in SICI, although we cannot exclude this possibility in the absence of a true placebo.

We used the stop signal reaction time to evaluate response inhibition at baseline and after treatment. Our pre-treatment findings were broadly consistent with those in other studies. We were surprised that there appeared to be a substantial improvement in SSRT in both clinical responders and non-responders. It is possible that ATX fairly consistently improved the capacity to inhibit in the laboratory, but that this did not generalize to improved behavior in the home or classroom. A practice effect may also have occurred. The physiology underlying these changes in SSRT appears to be distinct also from SICI and ICF, as these did not correlate with one another (not shown).

A significant limitation of this technique in this population was higher than expected resting depolarization thresholds. This appears to be primarily due to our inclusion of younger children in this cohort.10 This meant that a much smaller fraction of children than expected had SICI measured. Comparison of those in whom SICI was and was not measurable suggests that the main difference was younger age and therefore higher motor thresholds.37 With regard to implications for ADHD generalizability, we did not find evidence of a difference in ADHD symptoms in children with higher thresholds, in whom SICI was not measurable.

In summary, paradoxical changes in motor cortex inhibitory physiology appear to reflect behavioral improvements on ATX in children with ADHD. We did not find evidence that baseline SICI, in isolation, predicts treatment responses. More research is needed to clarify both excitatory and inhibitory components to these responses, to explain clinical heterogeneity, and to predict ATX treatment responses in advance.

Acknowledgments

Funding and

This research was funded in part by National Institutes of Health grant R01MH081854 (FRS) and the Swaimann Child Neurology Summer Research Fellowship (THC). Dr. Gilbert has received research funds as a site investigator for industry clinical trials in the past year from Otsuka and Psyadon pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sallee is a consultant for P2D Bioscience, Neos, Otsuka, Purdue Pharma, has received research support from Shire and Purdue Pharma and has stock in P2D Bioscience.

The study was conducted jointly in the department of psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati and the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The results of this study were presented at the 65th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in San Diego, California on March 21 and 22, 2013. There was no assistance in writing the manuscript that did not merit authorship. The authors thank the study families and participants for taking part in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

There are no other conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors approve submission of this work.

Ethical Approval

Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from parents/guardians with assent obtained from child subjects. The study was approved by both the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Author Contribution

Patients were under the direct care of a board-certified psychiatrist (FRS). Tina H. Chen, B.S. contributed to the manuscript through analysis and interpretation of study data, participating in acquisition of study data, writing the first draft and revising it for content, and obtaining funding. Steve W. Wu, MD contributed to the manuscript through providing study concept and design, participating in acquisition of study data, analysis and interpretation of study data, study supervision and coordination. Jeffrey A. Welge, PhD is a biostatistician who recommended and supervised the statistical analyses, and reviewed the manuscript for content. Stephan Dixon, BS contributed to the manuscript through participating in acquisition of study data, study supervision and coordination. Nasrin Shahana, MD contributed to the manuscript through providing study concept and design, participating in acquisition of data, reviewing and revising the manuscript for content. David A. Huddleston, BS contributed to the manuscript through providing study concept and design, participating in acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of study data, study coordination and supervision. Adam R. Sarvis, BS contributed to the manuscript through providing study concept and design, participation in acquisition of data, study coordination and supervision. Floyd R. Sallee, MD PhD is a principal investigator of the study and contributed to the manuscript through providing study concept and design, participating in acquisition of study data, analysis and interpretation of study data, study supervision and coordination, participating in reviewing and revising the content of the manuscript, and obtaining funding. Donald L. Gilbert, MD MSc is a principal investigator of the study and contributed to the manuscript through providing study concept and design, participating in acquisition of study data, analysis and interpretation of study data, study supervision and coordination, participating in writing the first draft of the manuscript, reviewing and revising the content of the manuscript, and obtaining funding.

References

- 1.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. The American journal of psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castellanos FX, Proal E. Large-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal-striatal model. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2012;16(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelson D, Faries D, Wernicke J, et al. Atomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Pediatrics. 2001;108(5):E83. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newcorn JH, Kratochvil CJ, Allen AJ, et al. Atomoxetine and osmotically released methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acute comparison and differential response. The American journal of psychiatry. 2008;165(6):721–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05091676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz KP, Fan J, Bedard AC, et al. Common and unique therapeutic mechanisms of stimulant and nonstimulant treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of general psychiatry. 2012;69(9):952–961. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moll GH, Heinrich H, Trott G, Wirth S, Rothenberger A. Deficient intracortical inhibition in drug-naive children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is enhanced by methylphenidate. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;284(1–2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moll GH, Heinrich H, Trott G, Wirth S, Bock N, Rothenberger A. Children with Comorbid Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder and Tic Disorder: Evidence for Additive Inhibitory Deficits Within the Motor System. Annals of Neurology. 2001;49:393–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moll GH, Heinrich H, Rothenberger A. Methylphenidate and intracortical excitability: opposite effects in healthy subjects and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;107(1):69–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchmann J, Wolters A, Haessler F, Bohne S, Nordbeck R, Kunesch E. Disturbed transcallosally mediated motor inhibition in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114(11):2036–2042. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert DL, Isaacs KM, Augusta M, Macneil LK, Mostofsky SH. Motor cortex inhibition: a marker of ADHD behavior and motor development in children. Neurology. 2011;76(7):615–621. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c2ebd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macneil LK, Xavier P, Garvey MA, et al. Quantifying excessive mirror overflow in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neurology. 2011;76(7):622–628. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mostofsky SH, Cooper KL, Kates WR, Denckla MB, Kaufmann WE. Smaller prefrontal and premotor volumes in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry. 2002;52(8):785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziemann U. TMS and drugs. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;115(8):1717–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Kujirai T. Short latency intracortical inhibition: one of the most popular tools in human motor neurophysiology. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 1):11–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1993;471:501–19. 501–519. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchmann J, Gierow W, Weber S, et al. Restoration of disturbed intracortical motor inhibition and facilitation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder children by methylphenidate. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(9):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider M, Retz W, Freitag C, et al. Impaired cortical inhibition in adult ADHD patients: a study with transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2007;(72):303–309. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-73574-9_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richter MM, Ehlis AC, Jacob CP, Fallgatter AJ. Cortical excitability in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Neuroscience Letters. 2007;419(2):137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert DL, Sallee FR, Zhang J, Lipps TD, Wassermann EM. TMS-evoked cortical inhibition: a consistent marker of ADHD scores in Tourette Syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1597–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoegl T, Heinrich H, Barth W, Losel F, Moll GH, Kratz O. Time course analysis of motor excitability in a response inhibition task according to the level of hyperactivity and impulsivity in children with ADHD. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e46066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert DL, Zhang J, Lipps TD, et al. Atomoxetine treatment of ADHD in Tourette Syndrome: Reduction in motor cortex inhibition correlates with clinical improvement. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1835–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. Kiddie-Sads-present and Lifetime version (K-SADS- PL) Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson J. School-based assessments and interventions for ADD students. Irvine, CA: KC Publishing; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Group RAS. The pediatric anxiety rating scale (PARS): Development and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1061–1069. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Axelrod BN. Validity of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence and other very short forms of estimating intellectual functioning. Assessment. 2002;9(1):17–23. doi: 10.1177/1073191102009001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guy W. Clinical global impression scale. The ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised. 1976;338:218–222. Volume DHEW Publ No ADM 76. [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklist, norms, and clinical interpretations. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert DL. Design and analysis of motor-evoked potential data in pediatric neurobehavioural disorder investigations. In: Wassermann EM, Epstein CM, Ziemann U, Walsh V, Paus T, Lisanby SH, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 389–400. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orth M, Snijders AH, Rothwell JC. The variability of intracortical inhibition and facilitation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114(12):2362–2369. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams BR, Ponesse JS, Schachar RJ, Logan GD, Tannock R. Development of inhibitory control across the life span. Developmental psychology. 1999;35:205–213. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbert DL, Ridel KR, Sallee FR, Zhang J, Lipps TD, Wassermann EM. Comparison of the inhibitory and excitatory effects of ADHD medications methylphenidate and atomoxetine on motor cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(2):442–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peurala SH, Muller-Dahlhaus JF, Arai N, Ziemann U. Interference of short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) and short-interval intracortical facilitation (SICF) Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(10):2291–2297. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilic TV, Meintzschel F, Cleff U, Ruge D, Kessler KR, Ziemann U. Short-interval paired-pulse inhibition and facilitation of human motor cortex: the dimension of stimulus intensity. J Physiol. 2002;545(Pt 1):153–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ni Z, Bahl N, Gunraj CA, Mazzella F, Chen R. Increased motor cortical facilitation and decreased inhibition in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1746–1753. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182919029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swanson CJ, Perry KW, Koch-Krueger S, Katner J, Svensson KA, Bymaster FP. Effect of the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder drug atomoxetine on extracellular concentrations of norepinephrine and dopamine in several brain regions of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50(6):755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nezu A, Kimura S, Uehara S, Kobayashi T, Tanaka M, Saito K. Magnetic stimulation of motor cortex in children: maturity of corticospinal pathway and problem of clinical application. Brain Dev. 1997;19(3):176–180. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]