Abstract

Objective

To determine whether earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is associated with better economic outcomes.

Design

Prospective cohort study of HIV positive patients on ART in rural Uganda.

Methods

Patients initiating ART at a regional referral clinic in Uganda were enrolled in the Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes study (UARTO) starting in 2005. Data on labor force participation and asset ownership were collected on a yearly basis and CD4 counts were collected at pre-ART baseline. We fitted multivariable regression models to assess whether economic outcomes at baseline and in the 6 years following ART initiation varied by baseline CD4 count.

Results

505 individuals, followed on average for 5 years, formed the estimation sample. Participants initiating ART at CD4≥200 were 13 percentage points more likely to be working at baseline (p<0.01, 95% CI 0.06-0.21) than those initiating below this threshold. Those in the latter group achieved similar labor force participation rates within 1 year of initiating ART (p<0.01 on the time indicators). Both groups had similar asset scores at baseline and demonstrated similar increases in asset scores over the 6 years of follow up.

Conclusion

ART helps participants initiating therapy at CD4<200 rejoin the labor force, though the findings for participants initiating with higher CD4 counts suggests that pre-treatment declines in labor supply may be prevented altogether with earlier therapy. Baseline similarities in asset scores for those with early and advanced disease suggest that mechanisms other than morbidity may help drive the relationship between HIV infection and economic outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, antiretroviral therapy (ART), employment, wealth, economic restoration, CD4 count, sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda

Introduction

The World Health Organization recently recommended earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), in particular at CD4+ T-cell lymphocyte cell (CD4) count >500 cells/mL [1]. These guidelines are based on evidence that earlier initiation reduces morbidity and mortality and lowers the risk of HIV transmission [2-4]. Earlier initiation may confer significant economic benefits as well. A growing body of work has shown that ART helps individuals resume employment after having been too sick to work [5-14]: earlier ART may prevent the pre-treatment declines in socioeconomic status altogether [15]. Moreover, earlier therapy may also augment subsequent economic recovery if those initiating ART at lower CD4 counts have difficulty achieving their pre-treatment economic status, perhaps due to reduced productivity from persistent morbidity or lower social mobility.

At present, the relationship between CD4 count at initiation and the trajectory of economic status is not well understood. A recent study demonstrated that individuals with CD4>200 in a rural Ugandan parish had similar labor force participation rates as HIV negative individuals [15]. However, this study did not explicitly focus on individuals on ART, nor did it examine differences in economic outcomes over time. To address this gap, we used data from an HIV cohort in rural Uganda to examine whether earlier initiation of ART was associated with a higher labor force participation rates and greater household asset ownership, both at ART initiation and through six years of follow-up.

Methods

Participants, Setting, and Data

We used data from the Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes (UARTO) Study, an ongoing cohort study of HIV-infected individuals initiating ART in rural, southwestern Uganda started in 2005. Previously ART-naïve persons 18 years of age or older initiating ART at the Immune Suppression Syndrome Clinic of the Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital were eligible for enrollment. Survey instruments were translated into the local Bantu language Runyankole, with interviews conducted by a native Runyankole speaker. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Institutional Review Committee, the Committee on Human Research at the University of California at San Francisco, and the Partners Healthcare Human Research Committee. Consistent with national guidelines, clearance for the study was granted by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and the Research Secretariat in the Office of the President.

Participants provided information on socioeconomic status and basic demographic characteristics at baseline and at yearly intervals thereafter. Our primary outcomes of interest were labor force participation and household asset ownership. Participants who reported engagement in any income-generating activity, whether in the informal (self-employment in trades, agriculture, etc.) or formal sectors, at the time of survey were considered as participating in the labor force. For asset ownership, we created an index representing the number of reported assets owned by the household out of 16 different durable goods (see Table 1 notes). Our primary explanatory variable of interest was baseline CD4 count, which was obtained via serum samples for all participants prior to initiating ART. We partitioned the sample into persons initiating ART at CD4<200 vs. those initiating ART at CD4≥200.

Table 1.

Association Between CD4 Count at Baseline and Trends in Labor Force Participation and Household Asset Ownership

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Labor Force Participation | Asset Score | |

| Baseline CD4 count | ||

| <200 | Ref | Ref |

| >200 | 0 13*** (0.057, 0.21) | 0.0049 (−0.47, 0.48) |

| Time on ART (years) | ||

| Baseline | Ref | Ref |

| 1 year | 0.12*** (0.051, 0.18) | 0.16 (−0.23, 0.56) |

| 2 years | 0.12*** (0.057, 0.19) | 0.39* (−0.016, 0.80) |

| 3 years | 0.16*** (0.10, 0.22) | 0.27 (−0.12, 0.66) |

| 4 years | 0.18*** (0.12, 0.24) | 0.70*** (0.30,1.10) |

| 5 years | 0.19*** (0.13, 0.25) | 0.95*** (0.52,1.38) |

| 6 years | 0.20*** (0.13, 0.28) | 1.17*** (0.65, 1.70) |

| Time on ART*CD4 Group Interactions | ||

| 1 year*CD4≥200 | −0.12* (−0.24, 0.013) | 0.21 (−0.48, 0.90) |

| 2 years*CD4≥200 | −0.16** (−0.31, −0.001) | −0.47 (−1.24, 0.30) |

| 3 year*CD4≥200 | −0.18** (−0.33, −0.025) | −0.2 (−0.93, 0.52) |

| 4 years*CD4≥200 | −0.13 (−0.29, 0.026) | −0.31 (−1.11, 0.49) |

| 5 years*CD4≥200 | −0.07 (−0.26, 0.12) | −0.11 (−0.93, 0.71) |

| 6 years*CD4≥200 | −0.20* (−0.44, 0.038) | 0.33 (−0.81, 1.47) |

| Number of Participants | 505 | 505 |

| Person Years | 2,349 | 2,349 |

Notes: Regression coefficients are reported with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Each column represents a separate regression.

- p<0.10

p<0.05

p<0.01. Confidence intervals computed using heteroskedasticity correct standard errors.

Models for Labor Force Participation were estimated using probit regression, with the dependent variable =1 if the individual reported participation in any formal or informal income generating activity at the time of interview. All models included controls for baseline age, age squared, a binary variable for gender, interactions between gender and baseline age, and binary indicators for marital status, completing some secondary schooling, and interview during the rainy season (see Table S2 for coefficient estimates on covariates). Reported coefficients are marginal effects. These can be interpreted as follows: for a continuous variable, the marginal effect coefficient reflects the percentage point increase in the probability of observing the dependent variable for a 1 unit change in the explanatory variable; for binary variables, it reflects a similar change in the dependent variable associated with a change from 0 to 1 on the explanatory variable of interest. Models for Asset Scores (integer ranging from 0-16, representing the count of the number of assets owned from the following: iron, gas or electric stove, refrigerator, telephone, motorbike, bicycle, car, clock, television, radio, bed, sofa, lantern, cupboard, and mattress) were estimated using ordinary least squares regressions.

For all models, the main explanatory variables were CD4 count at baseline and their interactions with the Time on ART dummy variables.

The “Number of Participants” refers to the number of unique individuals in the estimation sample. “Person Years” refers to the total number of Person-Year observations.

Statistical Analysis

We first plotted unadjusted trends in labor force participation by CD4 count at initiation. Second, we fit a probit regression model specifying labor force participation as the outcome variable and the following explanatory variables: (1) the baseline CD4 count (<200 vs. ≥200 ); (2) a set of binary indicators for each year since ART initiation; and (3) interactions between the CD4 and year indicators, so as to test whether the labor supply response to ART differed between the CD4 groups. We adjusted our models for age and age-squared interacted with gender, educational attainment, marital status, and season of interview (March-May and October-November rainy seasons). We presented labor force participation estimates as marginal effects (i.e., the percentage point increase in the probability of observing the dependent variable corresponding to a one-unit change in a continuous explanatory variable or a change from 0 to 1 for a dichotomous explanatory variable). For the household asset scores, we fitted regression models using ordinary least squares.

For both labor force participation and asset scores, we examined trends through six years after ART initiation. All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 13.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Tex.).

Results

Our sample consisted of 505 participants: 325 initiated ART at CD4<200 and 180 initiated ART at CD4≥200. Within the latter group, the median CD4 at initiation was 284 (IQR 233-360), with 47 (26%) initiating at ART at CD4≥350. Women comprised 70% of the sample and participants were, on average, surveyed at 5 annual time points. At baseline, participants initiating ART at CD4≥200 were more likely to be working compared to those initiating ART at CD4<200 (70% vs. 56%; χ2=9.15, p<0.01) but had similar asset index scores. Aside from marriage, there were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics (Table S1).

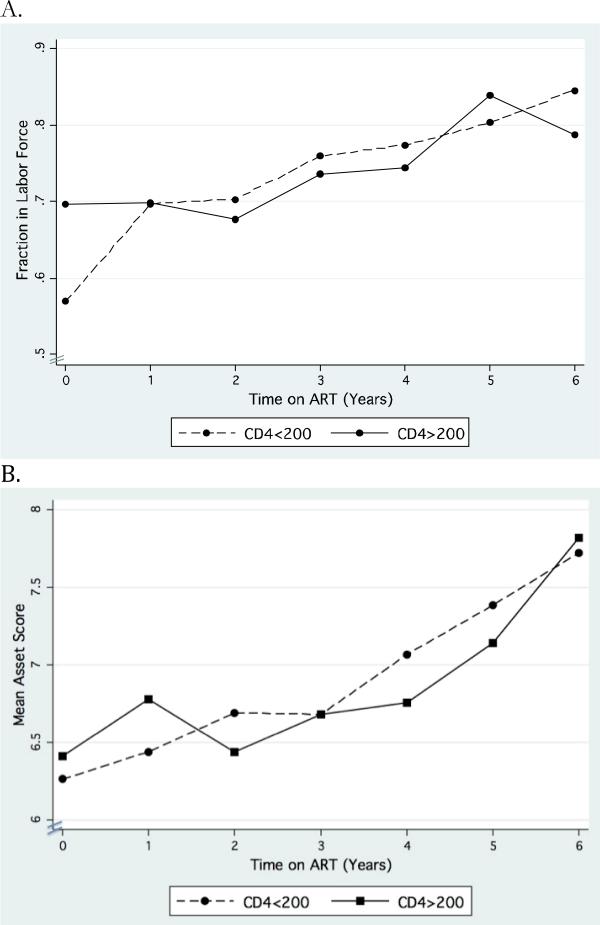

Figure 1 represents unadjusted trends in labor force participation and asset ownership. Although participants initiating ART at CD4<200 were less likely to be working at baseline, within one year of treatment initiation their average labor force participation rate converged to that of the participants initiating ART at CD4≥200. There were moderate increases for both groups thereafter, with participation rates around 80% at six-year follow-up (A). For asset scores, both groups started at similar levels and experienced gradual increases after initiating ART (B).

Figure 1.

Trends in Labor Force Participation and Household Asset Scores by CD4 Count at Time of ART Initiation

The multivariable regression results, shown in Table 1, were consistent with the patterns in Figure 1. As indicated by the regression coefficients on the CD4 count variable, participants initiating ART at CD4≥200 were 13 percentage points more likely to be working at baseline (column 1; b = 0.13, 95% CI 0.06-0.21). This group experienced little change labor force participation rates over baseline in the ensuing years: the sum of the interacted and non-interacted yearly indicator variables (which recovers the total change in participation rates relative to baseline for participants initiating ART at CD4≥200) was effectively zero for most of the six follow-up years. Those initiating at CD4<200, however, did experience increased labor force participation: the coefficients on the uninteracted yearly indicator variables indicate a 12-20 percentage point increase in the probability of working over baseline for each follow up year (F=61.24; p<0.01).

For asset scores (column 2), participants in the high CD4 count group owned a similar number of assets at baseline, and experienced gradual similar increases after starting ART, as participants in the low CD4 count group: the time dummies were collectively statistically significant (F = 6.25, p<0.01), but the coefficients on the interactions with the CD4 count dummy were not. For both models the associations between the outcomes and schooling, gender, and age were in the expected directions (Table S2).

We additionally estimated models including individual fixed effects, to control for time-invariant individual level confounders; the results were unchanged. In addition, we also excluded from the analysis all women who reported being pregnant at baseline (since they may have been less likely to work and more likely to access ART at higher CD4 counts). The substantive results again were unchanged. We also considered sample attrition and missing interview data, and ruled this out as a major source of bias in our comparisons of economic outcomes between the high and low CD4 groups (see Table S3 and associated notes). Finally, we examined whether economic status at baseline and over time differed for those initiating at CD4≥350. As shown in Figure S1 and Table S4, outcomes at baseline and at 1-2 years of follow up were substantively similar to those for initiating at CD4>200 and <350, though small sample sizes (only 47 participants initiated therapy at CD4≥350) precluded any definitive interpretation.

Discussion

Results from this cohort study of HIV-infected adults on ART in rural Uganda showed that participants initiating ART at CD4≥200 started out with higher labor force participation rates relative to their counterparts initiating ART at CD4<200. Within one year after starting ART, however, those initiating ART at CD4<200 had caught up and thereafter maintained similar trajectories in labor force participation: the overall six-year change in likelihood of working for adults initiating at CD4<200 was 20 percentage points. Interestingly, despite being more likely to be working at baseline, participants with higher CD4 counts at initiation reported similar household asset scores as the lower CD4 count group, with both groups experiencing increases in asset ownership over the study period.

These results have several policy implications. While those initiating ART at CD4<200 caught up quickly and experienced similar trajectories thereafter, earlier ART initiation may have prevented households from experiencing job loss and economic hardship in the first place, consistent with recent findings by Thirumurthy, et al [15]. Focusing on labor force participation alone, however, may mask more subtle impacts of HIV on individual and household socioeconomic outcomes. In particular, despite being more likely to work, participants with higher baseline CD4 counts started with similar asset scores as those initiating ART at lower CD4 counts. It may be that durable assets were being sold to make up for unmeasured declines in productivity or that participants, prior to treatment initiation, perceived shorter life-expectancies and therefore did not undertake long-term investments in productive assets [16]. These alternate mechanisms deserve further attention and motivate economic interventions at the time of diagnosis in order to prevent nonmorbidity related economic decline. Finally, continued improvements in socioeconomic position for all study participants six years after ART initiation demonstrates that economic impacts of ART may persist well after immune reconstitution is achieved.

This study has several limitations. First, the non-experimental study design limited our ability to make causal inferences. Second, we did not observe economic status prior to the baseline survey, limiting our ability to characterize the trajectory of pre-ART economic status. Third, we lacked data on alternate economic measures such as hours worked or wage earnings, which would have enabled us to better characterize subtle differences in productivity across the different CD4 count groups over the course of ART. Finally, it is unclear whether our findings generalize to other settings, though similarities in ART-led economic recovery across different countries suggest that some degree of generalization is reasonable [6, 10, 11].

Understanding the relationship between timing of ART initiation and economic deterioration is important for the design of ART guidelines and the valuation of the economic benefits of early ART initiation. Our study demonstrates that initiating ART at CD4>200 may have helped prevent job loss, though perhaps did not help stave off losses in household assets. Future research should examine a broader set of socioeconomic outcomes across a wider range of baseline CD4 counts (in particular the 350 and 500 thresholds identified in the 2010 and 2013 WHO guidelines), most optimally in the setting of a randomized controlled trial, to better identify ART initiation thresholds where economic status is not compromised.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the UARTO participants and staff for making this study possible. We also thank three anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Funding Sources

National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01MH054907 and P30A1027763. The authors also acknowledge salary support through K23MH087228, K24MH087227, K23 MH087228, K01HD061605, and K23MH096620.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The Uganda AIDS Rural Treatment Outcomes (UARTO) study is funded by the US

Author Contributions: A.S.V took the lead on study conception and design, performed data analysis, wrote the first draft of the article, and edited subsequent drafts.

H.T., J.H., Y.B.II, and M.J.S. assisted with study design, interpretation of the results, and made substantial edits and critical revisions to the article.

A.K. performed data collection and contributed to study design.

P.H. and J.M. participated in study conception and design, performed data acquisition, and performed article editing and revision.

D.B. was the principal investigator and developer of the UARTO study. He participated in study conception, design, article editing and revision.

A.C.T. supervised study conception, design, contributed to data analysis, provided critical interpretation of the results, and made substantial edits and critical revisions to the article. All authors were involved in the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Consolidated guidelines on general HIV care and the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. WHO; Geneva: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig S, Bang H, Severe P, Juste M, Ambroise A, Edwards A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of early versus standard antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults in Haiti. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8:e1001095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severe P, Juste M, Ambroise A, Eliacin L, Marchand C, Apollon S, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:257–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Early Antiretroviral Therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beard J, Feeley F, Rosen S. Economic and quality of life outcomes of antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in developing countries: a systematic literature review. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1343–1356. doi: 10.1080/09540120902889926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bor J, Tanser F, Newell M, Barninghausen T. In a study of a population cohort in South Africa, HIV patients on antiretrovirals had nearly full recovery of employment. Health Affairs. 2012;31:1459–1469. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habyrimana J, Mbakile B, Pop-Eleches C. The impact of HIV/AIDS and ARV treatment on worker absenteeism: implications for African firms. Journal of Human Resources. 2010;45:809–839. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nannungi A, Wagner G, Ghosh-Dastidar B. The impact of ART on the economic outcomes of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2013:362972. doi: 10.1155/2013/362972. doi: 362910.361155/362013/362972. Epub 362013 Jan 362928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen S, Larson B, Brennan A, Long L, Fox M, Mongwenyana C, et al. Economic outcomes of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in South Africa are sustained through three years on treatment. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012731. doi:12710.11371/journal.pone.0012731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thirumurthy H, Graff-Zivin J, Goldstein M. The economic impact of AIDS treatment: labor supply in Western Kenya. Journal of Human Resources. 2008;43:511–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thirumurthy H, Jafri A, Srinivas G, Arumugam V, Saravanan RM, Angappan SK, et al. Two-year impacts on employment and income among adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tamil Nadu, India: a cohort study. AIDS. 2011;25:239–246. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328341b928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lem M, Moore D, Marion S, Bonner S, Chan K, O'Connell J, et al. Back to work: Correlates of employment among person receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2005;17:740–746. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen S, Ketlhapile M, Sanne I, Desilva M. Differences in normal activities, job performance and symptom prevalence between patients not yet on antiretroviral therapy and patients initiating therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:S131–139. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327634.92844.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen S, Larson B, Rohr J, Sanne I, Mongwenyana C, Brennan A, et al. Effects of antiretroviral therapy on patients’ economic well being: five-year follow-up. AIDS. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000053. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thirumurthy H, Chamie G, Jain V, Kabami J, Krawrisiima D, Clark T, et al. Improved employment and education outcomes in households of HIV-infected adults with high CD4 cell counts: evidence from a community health campaign in Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27:627–634. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835c54d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baranov V, Kohler H-P. Mimeo. University of Pennsylvania; 2013. The impact of AIDS treatment on savings and human capital in Malawi. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.