Abstract

Background: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma; treatment with standard anthracycline-containing chemotherapy regimens has been disappointing, and an optimal treatment strategy for this patient population has not yet been determined.

Methods: We identified 15 cases of pathologically confirmed HSTCL in the institution's database. Clinical characteristics and treatment results were reviewed.

Results: Complete responses (CRs) were achieved in 7 of 14 patients who received chemotherapy. Achievement of CR was followed by hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in three patients. Median duration of CR was 8 months (range 2 to 32+ months) with four patients currently alive and in CR at 5, 8, 12, and 32 months, respectively. Median overall survival (OS) was 11 months (range 2 to 36+ months). Patients who achieved a CR had a median OS of 13 months, compared with 7.5 months in patients who did not achieve a CR. Risk factors associated with worse outcome included male gender, failure to achieve a CR, history of immunocompromise, and absence of a T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in the gamma chain.

Conclusion: A better understanding of the pathophysiology of HSTCL and new therapeutic strategies are needed.

Keywords: clinicopathological features, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, treatment

introduction

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Less than 100 cases have been described in the literature since the entity was first described in 1990 [1–5]. The term ‘gamma-delta hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma’ was included as a provisional entity in the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) classification, and after the identification of patients who demonstrated an alpha-beta phenotype with the clinicopathologic features of HSTCL, the term ‘hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma’ was adopted for use in the current World Health Organization classification [4, 6–11].

This condition is characterized by malignant T-cell proliferation in the sinusoids of the liver, sinuses and red pulp of the spleen, and sinuses of the bone marrow, and the commonly reported T-cell phenotype is CD2+, CD3+, CD4−, CD5−, CD7±, CD8−, with either gamma-delta or alpha-beta T-cell receptor expression [5, 12]. Associated cytogenetic abnormalities include isochromosome 7q with or without trisomy 8 [13–19]. Approximately 10% to 20% of afflicted patients have a prior history of immunocompromise, including renal transplantation, heart transplantation, Hodgkin's lymphoma, acute myelogenous leukemia, inflammatory bowel disease, and malaria infection [1, 5, 15, 20–28].

Treatment to date with standard anthracycline-containing chemotherapy regimens has been disappointing, with variable response rates, high relapse rates, and a short median survival of 8 months [1, 4, 5]. An optimal treatment strategy for this small patient population has yet been determined.

Herein, we summarize our experience with HSTCL at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) from 1997 to 2007. The purpose is to describe the clinical and biologic characteristics, to assess the impact of different risk factors, and to report on different treatment approaches for this frequently fatal disease.

methods

Patients with newly diagnosed HSL at MDACC from 1997 to 2007 were analyzed. Fifteen patients were identified and included in our study. We obtained the following data from patients’ medical charts: demographic information, histologic characteristics, immunophenotypic and molecular features, cytogenetics, treatment regimens, disease response, clinical course, and survival duration. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and a waiver of consent was obtained.

Summary statistics were used to describe the clinical, demographic, and survival characteristics of the study population. Subsets were identified by clinicopathological characteristics and treatment response. Response was defined using the International Workshop NHL criteria [29]. For the survival analyses, overall survival (OS) was the time between the diagnosis date and the patient's last follow-up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival distributions, and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival distributions between the groups. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were carried out using S-PLUS v7 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle, WA).

results

demographic and clinical characteristics

The patients' clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 38 years, with a range of 21–64. Six patients were female and nine patients were male. Four patients had a prior history of immunocompromise, including Sjogren's disease, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis, with each patient having received treatment with immunosuppressive medication.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at presentation

| Clinical characteristic | Number of patients (%) |

| Median age, years | 38 (range 21–64) |

| Sex (n = 15) | |

| Female | 6 (40) |

| Male | 9 (60) |

| History of immunocompromise | 4 (27) |

| Sjogren's disease, on intermittent prednisolone, methotrexate | 1 (7) |

| Crohn's disease, on chronic mercaptopurine | 1 (7) |

| Ulcerative colitis, chronic mercaptopurine, and mesalamine | 2 (13) |

| Sites of involvement | |

| Bone marrow | 15 (100) |

| Splenomegaly | 15 (100) |

| Liver involvement | 10 (67) |

| Hepatomegaly | 6 (40) |

| Biopsy-proven liver involvement in patients without hepatomegaly | 3 (20) |

| Abnormal LFTs | 6 (40) |

| Adenopathy | 2 (13) |

| Peripheral blood involvement | 4 (27) |

| B symptoms | |

| Fever | 10 (67) |

| Night sweats | 9 (60) |

| Weight loss | 8 (53) |

| Cytopenias | |

| Anemia | 8 (73) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 7 (64) |

| Neutropenia | 4 (36) |

LFTs, liver function tests.

At presentation, all assessable patients had splenomegaly and bone marrow involvement. Most patients presented with liver involvement (67%), anemia (73%), thrombocytopenia (64%), and reported at least one B symptom (80%). A minority of patients had adenopathy (13%), neutropenia (36%), or peripheral blood involvement (24%). One patient had lymphomatous involvement of the skin, a rare finding in HSTCL [12].

pathologic features, immunophenotype, molecular studies, and cytogenetic findings

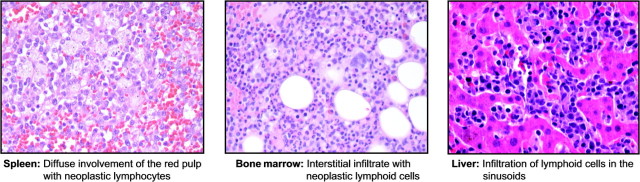

Figure 1 shows the typical histologic features of HSTCL in biopsies of bone marrow, liver, and spleen from two of the patients. Splenic involvement was characterized by diffuse involvement of the red pulp with small-to-medium-sized atypical lymphocytes. The atypical lymphocytes were present within the cords and sinuses of the red pulp. Characteristically, there was a marked reduction or complete loss of the white pulp. The liver showed sinusoidal infiltration by neoplastic lymphoid cells. The bone marrow was characterized by neoplastic cells in the sinusoids in the early stages, as opposed to an interstitial pattern of neoplastic infiltration in the later stages.

Figure 1.

Typical histological features of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in biopsies of spleen, bone marrow, and liver.

The immunophenotype of the tumor cells from each case is summarized in Table 2. The usual pattern of immunophenotypic expression was CD2+, CD3+, CD4−, CD5±, CD7±, CD8−, CD16±, CD56±, TIA-1+, TdT−, granzyme B±. Eleven patients (73%) had the gamma-delta T-cell receptor phenotype, and three patients (20%) had the alpha-beta T-cell receptor phenotype.

Table 2.

Immunophenotypic features

| Antigen | Patient number |

||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| T-cell receptor | GD | GD | AB | GD | GD | AB | GD | GD | AB | GD | GD | GD | GD | GD | GD |

| CD 2 | − | + | N/A | Dim | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | N/A | + |

| CD 3 | − | + | + | + | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD 4 | N/A | N/A | − | − | + | +/− | N/A | − | N/A | − | − | − | +/− | − | − |

| CD 5 | N/A | N/A | − | + | N/A | +/− | N/A | − | +/− | + | − | − | +/− | + | − |

| CD 7 | + | N/A | + | Dim | + | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| CD 8 | + | +/− | − | − | − | +/− | + | − | +/− | +/− | − | − | +/− | − | − |

| CD 16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | N/A | + | N/A | N/A | + | N/A | N/A | N/A | + | N/A | N/A |

| CD 56 | N/A | +/− | + | − | + | + | + | N/A | + | +/− | + | +/− | + | − | − |

| TIA-1 | + | + | + | N/A | + | N/A | + | + | N/A | − | + | + | + | + | N/A |

| TdT | − | − | N/A | N/A | − | − | − | N/A | − | − | − | − | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Granzyme B | N/A | N/A | + | N/A | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | + | − | +/− | N/A | N/A |

| Molecular rearrangments | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N | Y | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N/A |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | N/A | N | N | Y | Y | N/A | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N/A | Y |

GD, gamma-delta; AB, alpha-beta; N/A, not applicable.

T-cell receptor gene arrangements were detected in six of seven patients tested. The gene rearrangements included rearrangements of the beta chain (two patients) and the gamma chain (four patients), specifically in the V-gamma-I segment, as detected in three of the demonstrated four patients.

Among the 12 patients for whom cytogenetic studies were available, six patients were diploid and six were abnormal (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cytogenetic studies

| Patient number | Cytogenetic finding (n = 11) |

| 2 | Diploid |

| 3 | Diploid |

| 4 | 46XX, t(7;14)(q34q13) and 46, idem, del(2)(q32q37) |

| 5 | 45XY, der(13;14)(q10;q10) and 45XY, i(7)(q10), der(13;14)(q10;q10) |

| 7 | Diploid |

| 8 | 46XX, del(22q).ish22(WCP22×2) |

| 9 | Diploid |

| 10 | 43XY, −4, i(7)(q10), −13, −18[1] |

| 11 | 46XY, inv(9)(p11q12)[20] (normal variant) |

| 12 | Diploid |

| 13 | Diploid |

| 15 | 47X, −Y, i(7)(q10), +i(7)(q10), +8[5] |

treatment and outcome

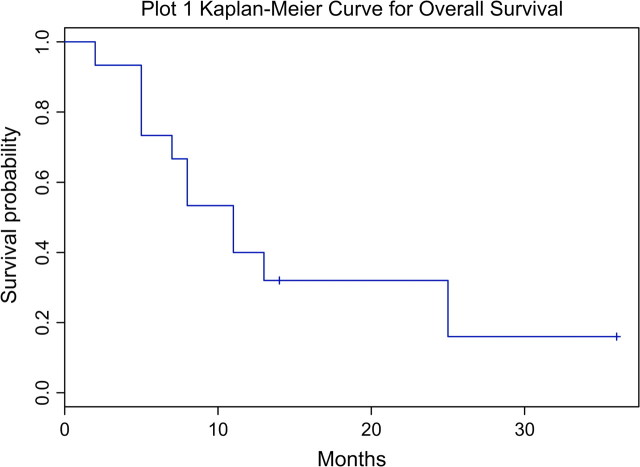

Patients received several different induction regimens depending on time period, performance status, and availability of clinical trials (Table 4). Median OS was 11 months (range 2 to 36+ months), with four patients still alive at 11, 13, 14, and 36 months (Figure 2). Complete responses (CRs) were achieved in 7 of 14 patients who received chemotherapy. Median duration of CR was 8 months (range 2 to 32+ months) with four patients still in CR at 5, 8, 12, and 32 months. Among the six patients treated with CHOP–CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) like regimens, two achieved a CR lasting 7 and 8 months, respectively. Four patients received fractionated cytoxan, liposomal doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone (HyperCVIDDoxil) alternated with methotrexate and cytarabine. Three achieved a CR and one achieved a partial response. Achievement of CR was followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation in one patient and allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in two patients.

Table 4.

Treatment

| Patient number | Treatment regimen | Response | Duration (months) | Survival (months) | Status |

| 1 | CHOP/MTX, AutoSCT | CR | 8 | 13 | Dead |

| ESHAP | NR | ||||

| Hyper-CVADMTX/AraC | NR | ||||

| 2 | IDSHAP/MBldCOS/MINE | CR | 2 | 5 | Dead |

| 3 | CHOP | CR | 7 | 25 | Dead |

| Pentostatin | PR | 2 | |||

| Pentostatin | PR | 2 | |||

| Denileukin diftitox | NR | – | |||

| 4 | CHOP | NR | – | 11 | Dead |

| Pentostatin | NR | – | |||

| ESHAP | NR | – | |||

| Liposomal ATRA | NR | – | |||

| 5 | CHOP | NR | – | 2 | Dead |

| 6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 11 | Dead |

| 7 | Cytoxan + etoposide + vincristine + bleomycin + methotrexate + prednisone | NR | – | 8 | Dead |

| HCVAD | NR | ||||

| Denileukin diftitox | NR | ||||

| 8 | Pentostatin/Alemtuzumab, AlloSCT | CR | 32+ | 36+ | Alive |

| 9 | Rituxan single agent | NR | – | 7 | Dead |

| CHOP | NR | – | |||

| Pentostatin + alemtuzumab | NR | – | |||

| DHAP | NR | – | |||

| ESHAP | NR | – | |||

| 10 | Hyper-CVIDD/MTX-Ara-C, AlloSCT | CR | 12+ | 14+ | Alive |

| 11 | Hyper-CVIDD | PR | 2 | 8 | Dead |

| Pentostatin | NR | ||||

| Gemcitabine | NR | ||||

| 12 | Hyper-CVIDD/MTX-Ara-C, AutoSCT | CR | 8+ | 13+ | Alive |

| 13 | Hyper-CVIDD/MTX-Ara-C | CR | 5+ | 11+ | Alive |

| 14 | Vincristine + decadron | NR | – | 5 | Dead |

| Gamma globulin | NR | ||||

| Cytoxan | NR | ||||

| 15 | CHOP | NR | – | 11 | Dead |

| DHAP | NR | ||||

| Liposomal ATRA | NR |

Ara-C, cytarabine; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CR, complete response; DHAP dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin; HyperCVAD, fractionated cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, vincristine; HyperCVIDD, fractionated cyclophosphamide, liposomal doxorubicin, dexamethasone, vincristine; IdSHAP, idarubicin, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin; MBIdCOS, methotrexate, leucovorin, doxorubicin, vincristine, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, methylprednisolone; MINE, mesna, ifosfamide, mitoxantrone, etoposide; MTX, methotrexate; NR, no response; PR. partial response.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival.

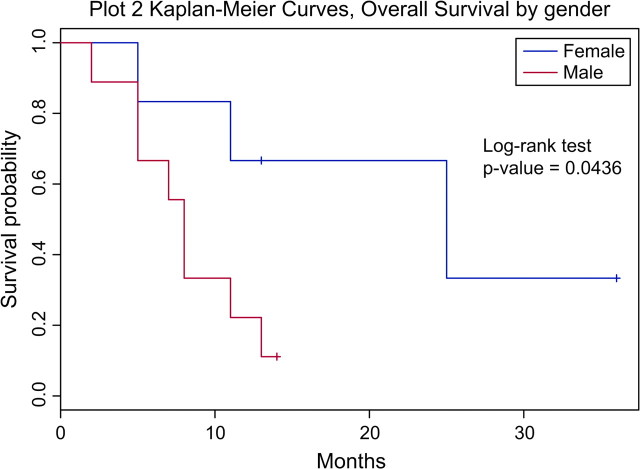

Patients who achieved a CR had a median OS of 13 months, compared with 7.5 months in patients who did not achieve a CR. All patients who received a hematopoietic stem-cell transplant are still alive and in CR at the time this paper is submitted for publication. Five of six female patients achieved a CR, compared with two of nine male patients. The median OS for female patients was 25 months, compared with 8 months for male patients (P = 0.0436) (Figure 3). Patients with a prior history of immunocompromise had a median OS of 6 months, compared with 11 months among patients without immunocompromise (P = 0.27). Patients with liver involvement at presentation had a median OS of 7.5 months, compared with 13 months among patients without liver involvement (P = 0.15). All the four patients who were found to have a T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in the gamma chain achieved a CR and are still alive in remission, with median OS of 13 months.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival by gender.

No trend in response or survival was noted for patient’s age, presence of ‘B’ symptoms, cytopenias at presentation, T-cell receptor status, or cytogenetics. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan findings in one patient with 2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose activity in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow correlated with response, but PET scans in another four patients did not correlate with disease activity. Gallium scans in five patients did not correlate with disease activity or clinical response.

discussion

Although HSTCL was first recognized as a distinct pathophysiological entity over 17 years ago, this aggressive neoplasm still lacks any standardized treatment guidelines. Moreover, survival duration for this disease varies widely—from 0 to 72 months—and no clinical feature or biomarker has been identified to reliably predict prognosis [5].

This study describes the clinicopathological features and treatment of 15 patients with HSTCL.

Several features of the patients in this study differed from the characteristics observed in previously published studies. Eleven patients had the gamma-delta T-cell receptor phenotype and three patients had the alpha-beta T-cell receptor phenotype. In contrast to prior descriptions of the gamma-delta phenotype occurring primarily in young men, 6 of the 11 patients with gamma-delta phenotype in our study were female. Conversely, while previous studies showed a predominance of the alpha-beta phenotype in females, our findings indicated that two of three such patients were in fact male [4].

Isochromosome 7q is a characteristic cytogenetic abnormality in HSTCL and has been proposed as the primary nonrandom cytogenetic abnormality which could play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Among the 12 patients for whom cytogenetic studies were available, six patients were diploid and six were abnormal. The presence of isochromosome 7q was documented in only three cases.

For the first time, we have tried to identify clinical characteristics that may assist in predicting survival. Gender was an important prognostic factor, as the median OS for female patients was 25 months, compared with 8 months for male patients with a P value of 0.04. There was a trend for better survival, albeit not statistically significant, for patients who achieved a CR with induction therapy and had a T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in the gamma chain. Unfavorable features included liver involvement at presentation and a previous history of immunocompromise.

As in previous reports, we confirmed the dismal prognosis of patients affected with this disease. The complete remission rate with various induction regimens was 50%, and in the majority of cases was short-lived with a median duration of 8 months. OS was also poor with a median survival of only 11 months (Table 4).

In our series, although in a limited number of patients, it appears that the regimen HyperCVIDDoxil alternated with methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine, resulted in a significant improvement in the rate of objective response. We are encouraged that the small cohort of patients who received stem-cell transplantation are alive and well, and we hope that longer follow-up will reveal durability of response and translate to long-term survival. In conclusion, HSTCL remains a rare disorder with a poor prognosis and there is an urgent need of effective treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joyce Palmer-Brown for her assistance in preparing and editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Belhadj K, Reyes F, Farcet J-P, et al. Hepatosplenic {gamma} {delta} T-cell lymphoma is a rare clinicopathologic entity with poor outcome: report on a series of 21 patients. Blood. 2003;102:4261–4269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooke CB, Krenacs L, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity of cytotoxic gamma delta T-cell origin. Blood. 1996;88:4265–4274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farcet JP, Gaulard P, Marolleau JP, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: sinusal/sinusoidal localization of malignant cells expressing the T-cell receptor gamma delta. Blood. 1990;75:2213–2219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macon WR, Levy NB, Kurtin PJ, et al. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphomas: a report of 14 cases and comparison with hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:285–296. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidmann E. Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma. A review on 45 cases since the first report describing the disease as a distinct lymphoma entity in 1990. Leukemia. 2000;14:991–997. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee Meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group [see comments] Blood. 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai R, Larratt LM, Etches W, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma of alphabeta lineage in a 16-year-old boy presenting with hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:459–463. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200003000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suarez F, Wlodarska I, Rigal-Huguet F, et al. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphoma: an unusual case with clinical, histologic, and cytogenetic features of gammadelta hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1027–1032. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group Classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;89:3909–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaulard P, Belhadj K, Reyes F. Gammadelta T-cell lymphomas. Semin Hematol. 2003;40:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0037-1963(03)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma in bone marrow. A sinusoidal neoplasm with blastic cytologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:410–419. doi: 10.1309/BM40-YM6J-9T3X-MH8H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonsozana EL, Stamberg J, Kumar D, et al. Isochromosome 7q: the primary cytogenetic abnormality in hepatosplenic gammadelta T cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 1997;11:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coventry S, Punnett HH, Tomczak EZ, et al. Consistency of isochromosome 7q and trisomy 8 in hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma: detection by fluorescence In situ hybridization of a splenic touch-preparation from a pediatric patient. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2:478–483. doi: 10.1007/s100249900152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francois A, Lesesve JF, Stamatoullas A, et al. Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma: a report of two cases in immunocompromised patients, associated with isochromosome 7q. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:781–790. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonveaux P, Daniel MT, Martel V, et al. Isochromosome 7q and trisomy 8 are consistent primary, non-random chromosomal abnormalities associated with hepatosplenic T gamma/delta lymphoma. Leukemia. 1996;10:1453–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang CC, Tien HF, Lin MT, et al. Consistent presence of isochromosome 7q in hepatosplenic T gamma/delta lymphoma: a new cytogenetic-clinicopathologic entity. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;12:161–164. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wlodarska I, Martin-Garcia N, Achten R, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization study of chromosome 7 aberrations in hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: isochromosome 7q as a common abnormality accumulating in forms with features of cytologic progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33:243–251. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao M, Tien HF, Lin MT, et al. Clinical and hematological characteristics of hepatosplenic T gamma/delta lymphoma with isochromosome for long arm of chromosome 7. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;22:495–500. doi: 10.3109/10428199609054788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan WA, Yu L, Eisenbrey AB, et al. Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma in immunocompromised patients. Report of two cases and review of literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:41–50. doi: 10.1309/TC9U-FAV7-0QBW-6DFC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraus MD, Crawford DF, Kaleem Z, et al. T gamma/delta hepatosplenic lymphoma in a heart transplant patient after an epstein-barr virus positive lymphoproliferative disorder. Cancer. 1998;82:983–992. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980301)82:5<983::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roncella S, Cutrona G, Truini M, et al. Late Epstein-Barr virus infection of a hepatosplenic gamma delta T-cell lymphoma arising in a kidney transplant recipient. Haematologica. 2000;85:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steurer M, Stauder R, Grnewald K, et al. Hepatosplenic [gamma ][delta ]-T-cell lymphoma with leukemic course after renal transplantation. Human Pathology. 2002;33:253–258. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.31301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassan R, Franco SA, Stefanoff CG, et al. Hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma following seven malaria infections. Pathol Int. 2006;56:668–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro JT, Ribera JM, Mate JL, et al. Hepatosplenic T-gammadelta lymphoma in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with azathioprine. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:531–533. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000035662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thayu M, Markowitz JE, Mamula P, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in an adolescent patient after immunomodulator and biologic therapy for Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:220–222. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200502000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackey AC, Green L, Liang LC, et al. Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma associated with infliximab use in young patients treated for inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:265–267. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802f6424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu H, Wasik MA, Przybylski G, et al. Hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma as a late-onset posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in renal transplant recipients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:487–496. doi: 10.1309/YTTC-F55W-K9CP-EPX5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]