Abstract

Background

This study assessed toxicity in advanced cancer patients treated in a phase I clinic that focuses on targeted agents.

Patients and methods

An analysis of database records of 1181 consecutive patients with advanced cancer who were treated in the phase I program starting 1 January 2006 was carried out.

Results

All patients were treated on at least 1 of the 82 phase I clinical trials. Overall, 56 trials (68.3%) had only targeted agents, 13 (15.9%) only cytotoxics, and 13 (15.9%) targeted and cytotoxic agents. Rates of grade 3 and 4 toxicity that were at least possibly drug related were 7.1% and 3.2%, respectively, and 5 of the 1181 patients (0.4%) died from toxicity that was at least possibly drug related. The most common grade 3 or more toxic effects were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, dehydration, infection, altered mental status, bleeding, vomiting, nausea, and diarrhea. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status greater than zero and use of a cytotoxic agent were selected as independent factors associated with serious toxicity.

Conclusion

Phase I trials of primarily targeted agents showed low rates of toxicity, with 10.3% of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 toxicity and a 0.4% rate of death, at least possibly drug related.

Keywords: chemotherapeutics, phase I, predictive factors, targeted therapies, toxicity

introduction

The development of effective cancer therapies is a national priority. In 2011, ∼570 000 Americans are expected to die of cancer [1]. Phase I studies with their primary end points of toxicity and safety play a critical role in drug development and approval.

Before the 1990s, phase I trials primarily evaluated investigational chemotherapeutic agents, whereas over the past 20 years, there has been a shift toward evaluation of more targeted agents in the phase I setting. The overall toxicity-related death rate reported previously has been low at ∼0.5%, even though most studies included trials mainly containing cytotoxic agents [2–9]. Most of the deaths and grade 3 and 4 toxic effects occurred in patients receiving chemotherapy versus targeted agents [8]. Toxicity rates in phase I trials are generally lower than those reported for most phase II and phase III studies, including many studies of drug combinations that have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [10, 11].

We initiated this study to determine the toxicity rate that was at least possibly drug related, in patients with advanced cancer treated in the phase I clinic at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. These patients were treated on regimens that included predominantly targeted agents. In addition, we sought to identify factors that were correlated with such toxic effects.

patients and methods

We reviewed the records of 1181 patients who presented to the phase I Clinical Trials Program at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2008 to determine the rates of death and serious toxic effects that were at least possibly drug related. Only patients who enrolled on a clinical trial were included. Treatment was determined after clinical, laboratory, and pathological data were reviewed. Investigational regimens available for patient enrollment varied over time.

Patient medical records were reviewed to identify patients who experienced clinical toxic effects that were evaluated as being related to study drug, both in the dose-limiting toxicity window and throughout the duration of treatment on each study. In addition, the Protocol Data Management System (PDMS), an electronic database of serious adverse events that are reported to the M. D. Anderson Institutional Review Board (IRB) was also reviewed, as were overview tables from each of the phase I clinical trials. Overview tables are an abbreviated database used by the department. These are compiled by the research nurse and reviewed weekly by the principal investigator. They are kept on all patients enrolled on a trial. The overview table includes information on patient demographics, drug, start and stop dates, course dates, response and grade 3 and 4 toxic effects, dose-limiting toxic effects, hospitalizations, and death. All patients had provided written informed consent before enrollment. This study and all treatments were carried out according to the guidelines of the M. D. Anderson IRB.

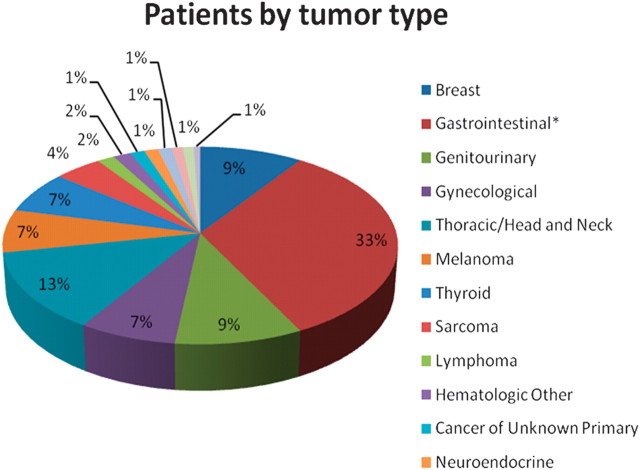

The patients who were included in this retrospective analysis had a broad range of primary tumor types (Figure 1). Patients were referred after failing standard therapy, or when standard therapy would be unlikely to confer a survival advantage.

Figure 1.

Pie chart showing percentage of patients in each tumor type (total n = 1181). Asterisk indicates that the gastrointestinal tumors include colon (n = 185); pancreas (n = 61); rectum (n = 46); esophagus (n = 26); appendix (n = 18); small intestine (n = 14); gastric (n = 12); hepatocellular (n = 11); cholangiocarcinoma (n = 8); anus (n = 6); peritoneum (n = 2); cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular (n = 2); and liver, not otherwise specified (n = 1).

After initiation of a phase I investigational therapy, patients were examined every 1–4 weeks depending on the protocol. At most visits, a review of recent patient history and physical examination were carried out along with a comprehensive metabolic and hematologic panel. Patients were assessed for the onset of new symptoms and compliance with the investigational therapy. In addition, symptoms reported by patients in the interim period between patient visits were triaged and assessed. Patients were monitored in real time (prospectively) for grade 3 to 4 toxic effects. Grade 3 and greater toxic effects were reviewed, and the subsequent toxicity attribution by the treating oncologist was assessed. These events and the associations between the study drug(s) and toxicity were reported to the IRB as per their guidelines. Only toxic effects that were at least possibly related to drug were included in our analysis. Toxic effects on the first phase I clinical trial were assessed and reported for both, the 1-month dose-limiting toxicity window and for the subsequent duration of the study.

end points and statistical methods

All statistics were carried out and/or verified by our statistician (SW). Toxic effects were assessed using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE), version 3.0 [12]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the patients' characteristics and toxic effects. Categorical data were described using contingency tables, including counts and percentages. The chi-square test and two-sample t-test were utilized to examine the association between toxicity (yes versus no) and categorical or continuous variables. Continuously scaled measures were summarized with descriptive statistical measures [i.e. mean (±SD) or median (range)]. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to assess the correlation between toxicity and patients' medical and demographical variables. All statistical tests were two-sided and P value <0.05 denoted statistical significance. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and S-Plus, version 7.0 (Insightful Corp, Seattle, WA) software.

results

A total of 1181 consecutive patients were identified who were treated in the phase I clinic starting on 1 January 2006. Their pretreatment and treatment characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table S1 (available at Annals of Oncology online). The median age was 58 years (range, 3–89 years), 44% of patients were >60 years, and 50% were women. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status [13] was 0 in 369 patients (31.2%), 1 in 705 (59.7%), 2 in 83 (7.0%), 3 in 7 (0.6%), and unknown in 17 patients (1.4%). ECOG performance status is zero or one in 91% of patients. Only 66 patients (5.6%) had not received any therapy for their advanced disease before coming to the phase I clinic and that was generally because of the unavailability of standard-of-care therapy options that increased survival. Among the 1115 patients who had received at least one prior treatment, the median number of prior treatments was 4 (range 1–17). The most common primary tumor site was the gastrointestinal tract (33%). Other baseline patient characteristics include 498 patients (42.2%) with liver metastases, 190 patients (16%) with a history of thromboembolism, 136 patients (12%) with elevated platelet levels (>440 K/Ul), 419 patients (35.5%) with elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (>618 IU/l), and 133 patients (11%) with low albumin levels (<3.5 g/dl).

treatments

Overall, 86% of our patients were enrolled in a study that included at least one targeted therapy and 68% of our patients were treated on a protocol without a chemotherapeutic agent. The composition of patients' treatment by study type is as follows: 528 (44.7%) patients were treated with a single targeted agent, 274 (23.2%) with a combination of targeted agents, 215 (18.2%) with targeted agents in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, 94 (8.0%) with a single cytotoxic agent, and 70 (5.9%) patients with more than one cytotoxic agent. A detailed breakdown of the 82 studies [industry-sponsored, 68; non-industry-sponsored, 14 (including 5 sponsored by NCI)] included in this analysis is as follows: single targeted agent, 46 studies (56.1%); combination of targeted agents, 10 studies (12.2%); targeted agents in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, 13 studies (15.9%); single cytotoxic agent, 10 studies (12.2%); and more than one cytotoxic agent, 3 studies (3.7%). Patients were treated on a median of 1 protocol (range, 1–9). A total of 893 patients were treated on only one protocol; 196 on two protocols; 66 on three protocols; 16 on four protocols; four on five protocols; two on six protocols; three on seven protocols; and, one patient was treated on nine protocols.

toxic effects

During treatment on a first phase I protocol, 122 patients (10.3%) experienced a grade 3 or 4 toxicity that was at least possibly drug related. The following patterns of toxicity among the 1181 patients were noted: hematologic (4.8%), gastrointestinal (3.6%), cardiac (1.5%), metabolic (1.5%), central nervous system (1.4%), constitutional (0.8%), pulmonary (0.8%), infection (0.8%), renal (0.4%), and vascular (0.1%) (Table 1). Many of these toxic effects are possibly related to drug effect and may be explained by the mechanism of action of these drugs. We evaluated common mechanisms of action among our trials and divided these groups by general mechanisms. We found that the following toxic effects may be related directly to cytotoxic agents: anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, mucositis, nausea, vomiting, infection, diarrhea, dehydration, hyponatremia, fatigue, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmia, hematuria, renal failure, bleeding, and altered mental status. The following toxic effects may be related to antiangiogenic agents: bleeding, cardiac arrhythmia, and angina. Altered mental status and seizures were likely related to treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Pleural effusions were possibly related to treatment with dasatinib. A subanalysis of 802 patients treated without cytotoxics revealed a serious toxicity (grade 3 to 4) rate at least possibly related to drug of 8.6%. Of 122 patients, 84 (7.1%) experienced a grade 3 toxicity and 38 (3.2%) a grade 4 toxicity that were at least possibly related to drug. Only nine patients (0.8%) had grade 3 or 4 toxicity on their first protocol that was assessed as ‘definitely’ related to study drug. The most common grade 3 and greater toxic effects were neutropenia (2.3%), thrombocytopenia (1.5%), anemia (0.9%), infection (0.9%), dehydration (0.9%), altered mental status (0.8%), nausea (0.7%), vomiting (0.7%), bleeding (0.7%), and diarrhea (0.6%). Five patients (0.4%) died secondary to events that were assessed as ‘possibly’ related to study drug. There were no deaths assessed as ‘probably’ or ‘definitely’ related to drug.

Table 1.

Description of Grade 3 to 4 toxic effects at least possibly drug-related in phase I clinic based on first clinical trial

| SAE group (n = 1181) | SAE sub-type | Drug-related toxicity (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Total | ||

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropenia | 12 (1.0) | 15 (1.3) | 27 (2.3) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (0.4) | 13 (1.1) | 18 (1.5) | |

| Anemia | 7 (0.6) | 4 (0.3) | 11 (0.9) | |

| Nonhematologic major organ system | ||||

| Liver | Elevated transaminases | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.5) |

| Elevated bilirubin | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Renal | Acute renal failure | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.3) |

| Hematuria | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Heart | Cardiac arrhythmia | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.5) |

| Angina | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Hypotension | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | |

| CHF decompensation | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Pericardial effusion | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Syncope | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Lung | Dyspnea | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.4) |

| Pleural effusion | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.3) | |

| CNS | Altered mental status | 8 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 9 (0.8) |

| Seizure | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Ataxia | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Headache | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Dysarthria | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Nonmajor organ system | ||||

| Dehydration | 10 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (0.9) | |

| Infection | 9 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (0.9) | |

| Bleeding | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.7) | |

| Nausea | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.7) | |

| Vomiting | 8 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.7) | |

| Diarrhea | 7 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (0.6) | |

| Fatigue | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.5) | |

| Mucositis | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.3) | |

| Pain | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.3) | |

| Anorexia | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Rash | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Bowel perforation | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Elevated lipase | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Thromboembolism | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Electrolytes | ||||

| Hyponatremia | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.4) | |

| Hypokalemia | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Hypophosphatemia | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | |

CHF, congestive heart failure; CNS, central nervous system; SAE, serious adverse event.

prognostic factors

The following variables were included in the univariate analysis: age (>60 versus ≤60 years), gender, tumor type (breast, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynecological, lung/thoracic/head and neck, and others), ECOG performance status (0, 1, 2, or 3), number of metastatic sites (≤2 versus >2), history of liver metastasis (yes versus no), history of thromboembolism (yes versus no), platelet levels (<140, 140–440, >440 K/Ul), albumin levels (<3.5 versus ≥3.5 g/dl), number of prior therapies (0–2 versus >3), use of chemotherapeutic agent(s) (yes versus no), use of multiple agent(s) (yes versus no), history of prior radiation (yes versus no), history of prior surgery (yes versus no), LDH levels [≤618 versus >618 IU/l, with 618 IU/l being the upper limit of normal (ULN)], and Royal Marsden Hospital (RMH) score (0 or 1 versus 2 or 3). The RMH score includes the following variables: albumin < 3.5 g/dl, LDH > ULN, and >2 sites of metastases. ECOG performance status of more than zero (P = 0.014), history of thromboembolism (P = 0.041), treatment that included a chemotherapeutic agent versus only targeted agent(s) (P = 0.006), and treatment with multiple agents (versus a single agent) (P = 0.039) were all significantly associated with grade 3 or 4 toxicity that was at least possibly drug related in univariate analysis (supplemental Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). There was a trend toward a significant association with toxicity for patients with a history of liver metastases (P = 0.083). A multivariate analysis using a multivariate logistic regression model fitted with stratification by tumor classification was carried out in two different ways. First, we carried out this analysis using individual variables that compose the RMH score as well as all other variables above but not the RMH score itself. A second analysis used the RMH score as well as all other variables above but not the individual variables of the score. Both analyses demonstrated the same two independent predictors of toxicity. The first of two independent predictors of toxicity is ECOG performance status more than zero [relative risk (RR) = 1.7, P = 0.011] with a rate of serious grade 3 to 4 toxicity at least possibly related to drug of 6.2% for patients with ECOG performance status less than one versus 12.2% for ECOG performance status of one or more. The second independent predictor is treatment on a first phase I trial that included a chemotherapeutic agent [versus only targeted agent(s)] (RR = 1.8, P = 0.001) with a rate of serious toxicity of 14.0% for trials including chemotherapeutic agent versus 8.6% for trials with only targeted agent(s). When the RMH score was included in the multivariate logistic model, independent predictors of toxicity were still ECOG performance status more than zero (P = 0.019) and treatment with a chemotherapeutic agent versus only targeted agent(s) (P = 0.002). A history of thromboembolism (P = 0.071) and prior surgery (P = 0.060) were marginally significant in the first analysis, while prior surgery (P = 0.086) and a history of liver metastases (P = 0.089) were marginally significant in the second analysis (supplemental Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

discussion

Relative to other studies published on toxicity in phase I trials, our report includes a high percentage of trials (84%) using at least one targeted agent and a low percentage of trials (31.7%) containing chemotherapeutic agent(s). The toxicity-associated death rate was 0.4% and the overall reported rate of serious (grade 3 to 4) toxic effects, assessed as at least possibly related to drug, was 10.3%.

Our results are remarkably consistent with previously published data that showed serious toxicity (grade 3 to 4) rates that were at least possibly drug related [8]. Most previous reports demonstrated decreased toxicity that was at least possibly drug related for targeted versus chemotherapy agents. When we carried out a subanalysis of serious toxicity that was at least possibly drug related for patients treated with non-chemotherapy-containing regimens, we found a serious (grade 3 to 4) toxicity rate of 8.6%. There are exceptions. One report, e.g. cited a toxic death rate of 1.2% among 78 patients treated on predominantly targeted therapies [14]. While our study had fewer chemotherapy-containing regimens than in other analyses, we failed to show an overall decrease in grade 3 to 4 toxicity that was at least possibly drug related compared with previous analyses that included a higher percentage of chemotherapy-containing regimens [2]. One explanation is that a plateau of reported toxicity that was at least possibly drug related has been reached. Because few investigators are willing to document with absolute certainty that toxicity is not drug related and many attributions are denoted as at least possibly related to study drug, it is possible that future studies will fail to show lower toxicity rates. Among 122 patients with grade three or more toxic effects that were at least possibly drug related on a first phase I treatment protocol, only 9 (0.8%) of 1181 patients had toxic effects that were assessed as definitely related to study drugs. It may be difficult to compare directly our results of toxic effects that were at least possibly drug related, reported for both the dose-limiting toxicity window and the subsequent duration of a first phase I study, with results of other studies that only report those toxic effects during the dose-limiting toxicity window. Several previous analyses included only toxicity that was at least possibly drug related during the dose-limiting toxicity window [7], and others did not specify the time frame of when toxicity occurred in their analyses [8, 15]. Comparing death-related toxic effects reported among different studies may similarly be difficult. Of the five deaths that we reported as possibly drug related, three (60%) occurred within the 1-month dose-limiting toxicity window. Regardless of these difficulties, the striking similarity in toxicity and death rates between studies are notable.

We identified two independent variables associated with toxicity that was at least possibly drug related: increasing ECOG performance status (≥1) and treatment with a chemotherapy-containing regimen (versus targeted agent(s) only). Additionally, there was a trend toward increased toxicity in patients with a history of thrombosis and prior surgery, a finding supported by previous data showing worse outcomes in these patients [16]. Neither RMH score nor the variables that constitute the score (low albumin, >2 metastatic sites, and elevated LDH levels), previously demonstrated as predictors of survival [14, 17], were predictive of toxicity in our patient population. Predictors of toxicity in phase I trials, therefore, do not appear to be the same as predictors of survival. However, when RMH was included in the analysis (as a single variable), there was a trend toward increased toxicity in patients with prior surgery and liver metastases. One limitation of this study is that we did not include response to treatment as a variable in our analysis. However, our previous studies failed to show higher response rates or longer progression-free survival in our patients treated at higher dose levels while toxicity did increase with dose [18]. Previous studies have identified other predictors of increased toxicity including the time period during which the study was submitted to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (the rates of serious toxic effects decreased from those reported in 1991–1994 to those reported in subsequent years 1995–1998 and 1999–2002); source of funding (higher treatment-related deaths in trials without an industry sponsor than in one with an identified industry sponsor) [8]; dose level at entry [those treated at dose levels of >50% of the final maximum tolerated dose (MTD) experienced greater toxicity than those treated at a lower dose]; age over 65 years [19]; elevated platelet levels (>450 × 109/l); low white blood cell levels; and gender (female) [15].

If transition to a biologically effective dose is considered as an end point versus establishing the MTD, lower doses of targeted therapies may, at times, achieve efficacy end points similar to higher doses at the MTD [18, 20]. This approach may result in further decrease in drug-related toxicity rates. Though it seems that, based on our observation, only 0.8% of serious toxicity was definitely related to drug, safety should not be the major impetus for lowering dose levels.

There were no deaths on our studies reported as ‘definitely’ related to treatment. All deaths (0.4%) were reported as ‘possibly’ related. This death rate was virtually identical to the 0.49% reported by Horstmann et al. [2] in phase I studies of 11 935 patients carried out from 1991 to 2002 [2]. Therefore, even with relatively nontoxic drugs and cautious dose-escalation schemas, achieving further reductions in death rate that was at least possibly drug related, below 0.5%, may not be a feasible goal.

In light of the low toxicity and death rates at least possibly related to treatment, the notion of early clinical trials as being dangerous and the threshold for further requirements aimed at decreasing toxicity needs to be carefully evaluated [21–23]. This is especially important to consider because the death rate due to tumor was substantially higher than the death rate that was at least possibly related to drug (0.4%). Taken together, these results suggest that phase I trials are a safe option for patients with advanced cancer and good performance status, who have failed conventional therapy.

disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

Previous presentation: Poster presentation at 2010 ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL.

references

- 1.American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horstmann E, McCabe MS, Grochow L, et al. Risks and benefits of phase 1 oncology trials, 1991 through 2002. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:895–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurzrock R, Benjamin RS. Risks and benefits of phase 1 oncology trials, revisited. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:930–932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoh K, Sasaki Y, Miyata Y, et al. Therapeutic response and potential pitfalls in phase I clinical trials of anticancer agents conducted in Japan. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1994;34:451–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00685653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estey E, Hoth D, Simon R, et al. Therapeutic response in phase I trials of antineoplastic agents. Cancer Treat Rep. 1986;70:1105–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decoster G, Stein G, Holdener EE. Responses and toxic deaths in phase I clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 1990;1:175–181. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a057716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith TL, Lee JJ, Kantarjian HM, et al. Design and results of phase I cancer clinical trials: three-year experience at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:287–295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts TG, Jr, Goulart BH, Squitieri L, et al. Trends in the risks and benefits to patients with cancer participating in phase 1 clinical trials. JAMA. 2004;292:2130–2140. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Hoff DD, Turner J. Response rates, duration of response, and dose response effects in phase I studies of antineoplastics. Invest New Drugs. 1991;9:115–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00194562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tkaczuk KH. Review of the contemporary cytotoxic and biologic combinations available for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Ther. 2009;31(Pt 2):2273–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randall LM, Monk BJ. Bevacizumab toxicities and their management in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 3.0. 2006. DCTD, NCI, NIH, DHHS March 31, 2003 http://ctep.cancer.gov. (31 December 2008, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arkenau HT, Barriuso J, Olmos D, et al. Prospective validation of a prognostic score to improve patient selection for oncology phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2692–2696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han C, Braybrooke JP, Deplanque G, et al. Comparison of prognostic factors in patients in phase I trials of cytotoxic drugs vs new noncytotoxic agents. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1166–1171. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vemulapalli S, Chintala L, Tsimberidou AM, et al. Clinical outcomes and factors predicting development of venous thromboembolic complications in patients with advanced refractory cancer in a phase I clinic: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:408–413. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arkenau HT, Olmos D, Ang JE, et al. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors for patients treated within the context of a phase I study: the Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1029–1033. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain RK, Lee JJ, Hong D, et al. Phase I oncology studies: evidence that in the era of targeted therapies patients on lower doses do not fare worse. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1289–1297. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachelot T, Ray-Coquard I, Catimel G, et al. Multivariable analysis of prognostic factors for toxicity and survival for patients enrolled in phase I clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:151–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1008368319526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodon J, Perez J, Kurzrock R. Combining targeted therapies: practical issues to consider at the bench and bedside. Oncologist. 2010;15:37–50. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrawal M, Emanuel EJ. Ethics of phase 1 oncology studies: reexamining the arguments and data. JAMA. 2003;290:1075–1082. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.8.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart DJ, Whitney SN, Kurzrock R. Equipoise lost: ethics, costs, and the regulation of cancer clinical research. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2925–2935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart DJ, Kurzrock R. Cancer: the road to Amiens. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:328–333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.9621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.