Abstract

Characterizing local chicken types and their mostly rural production systems is prerequisite for designing and implementing development and conservation programs. This study evaluated the management practices of small-scale chicken keepers and the phenotypic and production traits of their chickens in Oman, where conservation programs for local livestock breeds have currently started. Free-range scavenging was the dominant production system, and logistic regression analysis showed that socio-economic factors such as training in poultry keeping, household income, income from farming and gender of chicken owners influenced feeding, housing, and health care practices (p<0.05). A large variation in plumage and shank colors, comb types and other phenotypic traits within and between Omani chicken populations were observed. Male and female body weight differed (p<0.05), being 1.3±0.65 kg and 1.1±0.86 kg respectively. Flock size averaged 22±7.7 birds per household with 4.8 hens per cock. Clutch size was 12.3±2.85 and annual production 64.5±2.85 eggs per hen. Egg hatchability averaged 88±6.0% and annual chicken mortality across all age and sex categories was 16±1.4%. The strong involvement of women in chicken keeping makes them key stakeholders in future development and conservation programs, but the latter should be preceded by a comprehensive study of the genetic diversity of the Omani chicken populations.

Keywords: Animal Genetic Resources, Egg Production, Rural Smallholders, Scavenging System, Task Division

INTRODUCTION

Local chickens play an important role for smallholders and contribute significantly to food security of households in rural and semi-urban communities (Abdelqader et al., 2007). According to Jens et al. (2004), nearly all rural and semi-urban families in developing countries keep a small flock of local chickens in the backyard. Scavenging systems and low input into feeding, housing and labor as well as adaptation to diseases, absence of veterinary services and poor management (Hall, 1986) are considered as the main characteristics of local chicken production systems in tropical and subtropical countries (Aini, 1990; Gueye, 2000). A considerable phenotypic variation is another main characteristic of local chicken types throughout the world (Mcainsh et al., 2004). Women are frequently in charge of local chicken husbandry (Mwalusanya et al., 2002) and are especially involved in most activities of poultry management, although a division of labor often exists within the household (Kondombo et al., 2003). However, rural communities often lack the required husbandry skills, training and market opportunities to effectively improve their chicken production (Mwalusanya et al., 2002).

In Oman where more than 40% of the population is still engaged in the agricultural sector (MONE, 2010), no studies have been carried out so far to characterize and develop the rural chicken production systems for conservation purposes. Since the design of conservation and development programs requires full characterization of village production systems (Gueye, 2000), the current study aimed at analyzing i) Omani rural chicken populations in terms of phenotypic diversity; ii) small-scale chicken production systems and marketing strategies in Oman’s major agro-ecological zones; iii) local chickens’ productive and reproductive potential under different management conditions; and iv) overall opportunities and constraints of traditional small-scale chicken farming in Oman.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study locations, interviews and data collection

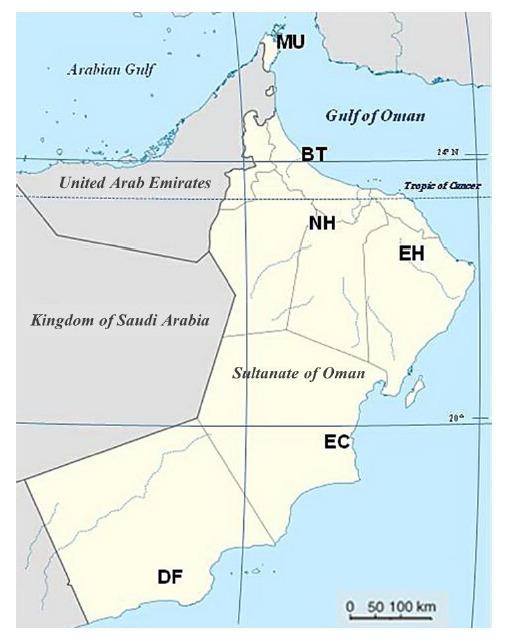

The study was carried out in the six major agro-ecological zones (AEZ) of Oman, namely Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), and Dhofar (DF). These zones (Figure 1) are clearly apart from each other and differ widely in topographic aspects, climate (Table 1), soils and agricultural production systems (MOAF, 2008).

Figure 1.

Location of the agro-ecological zones Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), and Dhofar (DF). Source: Ministry of National Economy Oman (2008).

Table 1.

Climatic averages and topographic features of the studied six agro-ecological zones in Oman

| Agro-ecological zone | Monthly average temperature (°C) | Yearly average humidity (%) | Rainfall (mm/yr) | Max. altitude(m asl) | Farming activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musandam (MU) | 18 (Dec) – 36 (Jul) | 90 | 192 | 1,800 | Livestock, fisheries, some crop cultivation |

| Batinah (BT) | 15 (Dec) – 35 (Jul) | 63 | 99 | 1,000 | Fruits, vegetables and crop cultivation, livestock, fisheries |

| North Hajar (NH) | 14 (Jan) – 35 (Jul) | 25 | 345 | 3,000 | Fruit and crop cultivation, livestock |

| East Hajar (EH) | 15 (Dec) – 34 (Jul) | 70 | 30 | 2,000 | Fruit and crop cultivation, livestock |

| East Coast (EC) | 18 (Dec) – 34 (Jul) | 80 | 67 | 100 | Livestock, fisheries |

| Dhofar (DF) | 18 (Jan) – 32 (May) | 88 | 200 | 2,000 | Fruit, vegetable and fodder cultivation, livestock |

Source: Ministry of Environmental Affairs Oman (2008), Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Three villages were selected from each AEZ according to the information given by the regional Agricultural Directorates. In cooperation with agents of the local agricultural extension centers, a preliminary survey was conducted to gather principal information concerning small-scale farmers in the six major AEZs. A total of 163 households were selected for the detailed study (20–30 households from each AEZ, distributed across 3 villages) using a stratified sampling method. In each AEZ the selected farms had similar agricultural systems and were representative for the zone. Villages in close proximity to large cities were avoided.

The households in the study villages were visited and data were collected using a pre-tested structured questionnaire covering households’ socio-demographic and economic characteristics, and characteristics of their livestock and cropping activities in general. Number of chickens, egg production, health care, feeding and housing strategies, bird ownership as well as decision-making were recorded. Normally the head of the family (householder) or flock caretakers were interviewed once during the study period. However, in some cases the visit was repeated on selling and purchasing days of new chicken stocks or when new houses for the chicken were built.

Measuring morphological traits of chicken

A total of 199 adult chickens aged 9 to 12 months were selected for the assessment of phenotypic traits according to the following distribution: DF, 20 females, 6 males; EC, 25 females, 6 males; EH, 28 females, 6 males; MU, 30 females, 6 males; NH, 30 females, 6 males; BT, 30 females, 6 males. Variables measured included body weight, body length (distance from the beginning of the neck to the tail) and shank length (length of the tarsometatarsus from the hock joint to the metatarsal pad). Body and shank lengths were measured using a graduated tape while the bird was standing upright; body weight was measured in kilogram using an electronic hanging scale (accuracy 0.01 g). The recorded morphological traits included plumage, eye, comb, and shank colors and patterns. Data collection was completed by taking a picture of each surveyed bird.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics on the phenotypic traits were computed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). For the management part, data analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, IL). Differences between AEZ were explored using Chi-square test (categorical variables) or Kruskal-Wallis test (continuous variables), whereby continuous variables were first tested for normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was computed to assess the major mean ranks of chicken traits given priority by flock owners when selecting new chicken flocks. The major farming activities of households were assessed using weighted means procedures, with each activity being weighted according to its order among the three first important activities.

A stepwise logistic regression with backward elimination of predictors (Hair et al., 2006) was used to relate chicken keepers’ adoption of supplementary feeding of birds (yes/no) and of solid housing (yes/no) to independent predictors. Several independent variables (among others, AEZ, age of householder, total household income, farm contribution to total income, cropland size, chicken flock size, years of experience in chicken keeping, training in poultry keeping) were included in the full model (Eq. 1). Variables that were not useful in predicting the dependent variables were eliminated automatically from the model in an iterative way.

| (Eq. 1) |

where Y is the dependent variable, and β′ = (β0, β1…) the model parameters to be estimated, ɛ the error term and Xi the independent variables.

The fit of the final model was assessed by the model Chi-square (Model X2) and the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (Archer and Lemeshow, 2006). Well-fitting models showed significance (p<0.05) on the Model X2 and non-significance (p>0.05) on the goodness-of-fit test.

A multiple linear regression (Eq. 2) was used to predict chicken flock size, egg production, and bird survival rate from different socio-economic and management variables (among others, family size, gender and age of chicken owner, years of experience in chicken keeping, daily scavenging period, offer of commercial feeds, equipment use, presence of a solid chicken house, presence of hired labor, cleaning of chicken house and utensils, administration of medicine) as follows:

| (Eq. 2) |

where Y is the dependent variable, a the intercept, bi the regression coefficient, ɛ the error term and Xi the predictor variable.

RESULTS AND DISSCUSSION

Household socioeconomic characteristics and farming activities

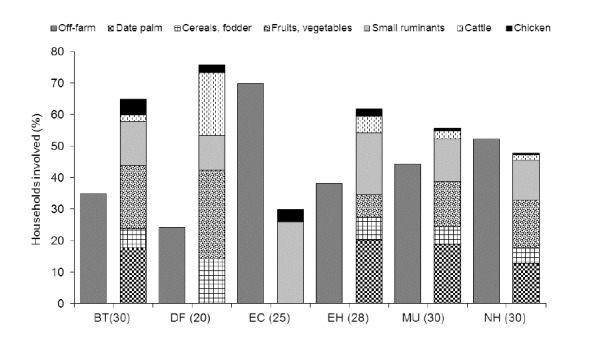

Of the interviewed 163 householders, 125 (76.8%) were male and 38 (23.2%) female (Table 2). On a weighted means basis, date palm cultivation, small ruminant husbandry, fruit and vegetable cropping and cereal and fodder cultivation were the most important farming activities in BT, EH, NH, and MU (Figure 2). In DF, the major farming activity was fruit and vegetable cropping, while in EC small ruminant husbandry was dominant. Chicken husbandry is a widely spread activity of rural smallholder farmers across Oman even though, from an economic point of view, its importance is inferior to that of the production of dates, cereals and fodder crops, fruits and vegetables and ruminant livestock (Figure 2). For 68.9% of the respondents the main reason for keeping chickens was home consumption of eggs and meat, whereas 31.3% reported to sell some of the live chickens and eggs (Table 2). However, the exact contribution of chicken to household income and self-sufficiency in poultry meat and eggs could not be determined, partly due to lack of reliable production data and recalls.

Table 2.

Household characteristics, ownership patterns, and responsibilities for and purpose of keeping local chicken flocks by 163 smallholder farmers across six agro-ecological zones of Oman1

| Variable | Agro-ecological zone2 | Mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| MU n = 30 |

BT n = 30 |

NH n = 30 |

EH n = 28 |

EC n = 25 |

DF n = 20 |

||

| Household head, sex | |||||||

| Female | 16.7 | 33.3 | 26.6 | 21.4 | 16.0 | 25.0 | 23.2 |

| Male | 83.3 | 66.7 | 73.4 | 78.6 | 84.0 | 75.0 | 76.8 |

| Age/sex group of chicken owners | |||||||

| Children (<15 yr) | 3.3 | 3.3 | 6.4 | 9.9 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 5.1 |

| Male (15–60 yr) | 13.5 | 8.9 | 10.7 | 17.8 | 16.1 | 10.8 | 13.0 |

| Female (15–60 yr) | 74.4 | 77.6 | 69.0 | 60.7 | 64.0 | 79.2 | 70.8 |

| Older members (>60 yr) | 8.8 | 10.2 | 13.9 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 10.0 | 11.2 |

| Source of specific knowledge of chicken owner | |||||||

| Traditional knowledge | 62.1 | 46.7 | 56.7 | 69.7 | 82.0 | 65.9 | 63.8 |

| Technical training | 37.9 | 53.3 | 43.3 | 30.3 | 18.0 | 34.1 | 36.2 |

| Responsible for feeding, watering, cleaning and collecting eggs | |||||||

| Wives and children | 64.7 | 44.2 | 64.4 | 69.6 | 70.7 | 38.5 | 58.7 |

| Husband | 17.8 | 17.8 | 22.8 | 15.3 | 17.0 | 20.0 | 18.5 |

| External labor | 17.4 | 37.8 | 12.8 | 15.1 | 12.3 | 41.7 | 22.9 |

| Responsible for maintenance of chicken houses and assets | |||||||

| Husbands | 27.8 | 14.9 | 33.8 | 29.1 | 32.9 | 11.0 | 23.4 |

| External labor | 72.2 | 85.1 | 66.2 | 70.1 | 67.1 | 89.0 | 76.6 |

| Responsible for selecting and purchasing birds, and selling products | |||||||

| Wives | 91.1 | 83.3 | 89.9 | 84.4 | 95.3 | 71.1 | 85.9 |

| Husband | 8.9 | 16.7 | 10.1 | 15.6 | 14.7 | 28.9 | 15.8 |

| Purpose of keeping local chicken | |||||||

| Home consumption and income | 36.7 | 23.3 | 36.7 | 24.1 | 41.6 | 25.5 | 31.3 |

| Home consumption only | 63.3 | 76.7 | 63.3 | 75.9 | 59.4 | 74.5 | 68.9 |

All values are percentages of occurrence in the different zones and across the zones (last column). Sums of percentages per category can deviate from 100.

Agro-ecological zones: Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), Dhofar (DF).

Figure 2.

Off-farm engagement and major agricultural activities of 163 smallholder farmers across six agro-ecological zones of Oman as derived from weighted means computation. Zones are Batinah (BT), Dhofar (DF), East Coast (EC), East Hajar (EH), Musandam (MU) and North Hajar (NH). Figures in parenthesis depict the number of interviewed households per zone.

Ownership and task division in chicken farming

Although the householders across the studied regions were mostly men, chicken ownership was dominated by females in all AEZ; they controlled the inflow and outflow of birds and were involved in selling and selecting new flocks. Within the family, chickens were primarily owned by women aged 15–60 years (70.8%; Table 2). Women and children below 15 years of age were strongly involved in daily chicken management, especially feeding, watering and egg collection (58.7%; Table 2). External (male) laborers and husbands were primarily responsible for the maintenance of the chicken houses and equipment. The selection of birds among growing chicks and the purchasing of new birds for breeding or replacement was the task of women (85.9%).

As far as specific selection criteria for new chickens were concerned, all respondents selected replacement chickens based on one or more criteria, in particular egg production, egg size, body size and growth rate of the mother, body conformation and feather color (Table 3). When selecting hatching eggs, farmers declared that eggs for the next generation should be collected from hens with a good performance history.

Table 3.

Mean rank1 and placement2 of criteria for the selection of replacement chickens provided by 163 smallholder farmers across six agro-ecological zones3 of Oman

| Variable | Mean rank | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| MU n = 30 |

BT n = 30 |

NH n = 30 |

EH n = 28 |

EC n = 25 |

DF n = 20 |

|

| Major selection traits | ||||||

| Egg production | 2.5 (1) | 2.3 (1) | 2.1 (1) | 2.3 (1) | 2.2 (1) | 2.2 (1) |

| Egg size | 3.3 (4) | 3.5 (5) | 3.9 (5) | 3.5 (5) | 3.7 (5) | 3.5 (5) |

| Body size and growth rate | 2.8 (2) | 2.5 (2) | 2.3 (2) | 2.5 (2) | 2.5 (2) | 2.8 (2) |

| Body conformation | 3.4 (5) | 3.3 (3) | 3.4 (4) | 3.3 (3) | 3.4 (4) | 3.4 (4) |

| Feather color | 3.0 (3) | 3.4 (4) | 3.3 (3) | 3.4 (4) | 3.3 (3) | 3.0 (3) |

| W 4 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.14 |

Mean rank: 1 highest, 5 lowest.

Placement (rank) across all variables per zone given in brackets.

Agro-ecological zone: Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), Dhofar (DF).

W: Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance (0 = no agreement, 1 = total agreement).

Housing and feeding management

The respondents used different locally available and cheap building materials for constructing chicken houses; these only hosted birds belonging to the family. Wood sticks and sheets, palm leafs, fabric and corrugated iron were the main materials used. Solid concrete and stone houses were relatively frequent in MU and BT (Table 4). Light was hardly available in the chicken houses, however, electrical pear lamps for brooding were frequent in DF (75%), while fans for air circulation were very rarely used across all AEZ (7%). Preparing nesting boxes for the hens was common in all AEZ but least frequent in EC. Nests were made from cheap local materials such as a large tin with cut ends or wood.

Table 4.

Construction material for chicken houses, housing equipment and feeding system used by 163 smallholder farmers across six agro-ecological zones of Oman1

| Variable | Agro-ecological zone2 | Mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| MU n = 30 |

BT n = 30 |

NH n = 30 |

EH n = 28 |

EC n = 25 |

DF n = 20 |

||

| Construction material | |||||||

| Wooden and iron sheet | 50.1 | 50.7 | 66.7 | 67.8 | 92.0 | 69.2 | 66.1 |

| Concrete/mud | 29.9 | 39.4 | 23.3 | 21.4 | 4.0 | 20.4 | 23.1 |

| Palm leaves and fences | 20.0 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 4.0 | 10.4 | 10.9 |

| Existence of management assets | |||||||

| Brooding lamp | 20.0 | 26.7 | 16.2 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 75.0 | 27.2 |

| Laying nests | 43.3 | 53.3 | 43.3 | 28.6 | 8.7 | 39.8 | 36.1 |

| Air circulation fans | 8.0 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 6.7 |

| Approved feeders and water troughs | 36.6 | 71.9 | 58.0 | 22.2 | 20.3 | 75.9 | 47.5 |

| Feeding system | |||||||

| Scavenging only | 33.5 | 26.7 | 33.3 | 47.1 | 53.5 | 55.0 | 41.5 |

| Use of commercial supplements | 66.5 | 73.3 | 66.7 | 52.9 | 46.5 | 45.0 | 58.5 |

All values are percentages of use by farmers in the different zones and across the zones (last column). Sums of percentages per category can deviate from 100.

Agro-ecological zone: Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), Dhofar (DF).

During daytime, birds were released to scavenge freely the agricultural by-products and household wastes on the fields or in the home garden or close to their shelters. During night they were confined in their houses. However, commercial supplements (mainly feed concentrates) were additionally given to the birds by 58.5% of the respondents. The scavenging system with the use of household wastes and plant by-products was also reported from Malawi (Gondwe, 2004), Ethiopia (Dessie and Ogle, 2001) and Burkina Faso (Kondombo et al., 2003). However, the nutrient values of such scavenged by-products and wastes need to be evaluated. Abdelqader et al. (2007) suggested that meeting the nutrient requirements of scavenging chicken depends on the available scavenging area per bird, the quality of scavenging feed resources, the season and the birds’ production stage.

The care of farmers for their bird flocks was of interest in our study. A binary logistic regression was employed to investigate farmers’ decision to house their flock in solid houses and to feed them a commercial supplemental feed (Table 5). Training in poultry husbandry, cropland area, contribution of farm income to household income and flock size showed a significant (p<0.05) and positive correlation with keeping the birds in solid houses. Training in poultry keeping and a higher total household income increased the likelihood of offering supplement feeds to chicken (p<0.05). Resource availability might at least partly have influenced the type of housing structures chosen by the famers (Ramlah, 1996). For Botswana, Badubi et al. (2006) reported that good housing improved flock productivity in free-range scavenging systems.

Table 5.

Coefficients of the logistic regression models predicting the decision of 163 smallholder farmers to keep local chickens in solid houses (above) and to offer purchased supplementary feed (below) across six different agro-ecological zones of Oman

| Regression parameters | β | SEβ | Wald’s x2 | df | p≤ | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Keep chicken in solid house (yes) | ||||||

| Constant | −16.35 | 3.85 | 18.02 | 1 | 0.001 | n.a. |

| Training in poultry keeping (yes = 1) | 3.91 | 1.16 | 11.29 | 1 | 0.001 | 49.72 |

| Cropland size (feddan)1 | 1.44 | 0.51 | 7.86 | 1 | 0.005 | 4.20 |

| Farming contributes to income (yes = 1) | 4.47 | 1.40 | 10.16 | 1 | 0.001 | 87.18 |

| Chicken flock size (n) | 0.29 | 0.09 | 10.18 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.33 |

| Overall model evaluation (Model X2) | 152.44 | 4 | 0.001 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit test2 | 45.27 | 8 | 0.691 | |||

| Dependent variable: Offer commercial supplement feeds (yes) | ||||||

| Constant | −10.92 | 1.92 | 30.89 | 1 | 0.001 | n.a. |

| Total income of household (OMR/yr)1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 30.20 | 1 | 0.001 | 1.02 |

| Training in poultry keeping (yes = 1) | 3.94 | 1.29 | 9.22 | 1 | 0.002 | 51.28 |

| Overall model evaluation (Model X2) | 155.94 | 2 | 0.001 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit test2 | 5.43 | 6 | 0.49 | |||

Units: feddan = Arabic unit of area, 4200 m2; OMR = Omani Rial, exchange rate 1 OMR = 2.6 USD

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness-of-fit test (Archer and Lemeshow, 2006).

n.a.= Not applicable; for binary variables, yes = 1 and no = 0.

The significant effect of flock size indicated that farmers provided better protection from predators and environmental conditions when chicken numbers increased. Yet, income from farming and training in poultry keeping were the strongest predictors for improved housing.

Approximately 36% of the interviewees benefited from technical services provided by extension agents or veterinarians, or had received advises and technical training in poultry management (results not shown). Training in poultry husbandry by extension agents increased the farmers’ likelihood to offer commercial supplement feed to their birds, pointing to the effectiveness of extension programs in improving the productivity of the chicken business. Adebayo and Adeola (2005) indicated that the relationship between skill level and flock production is directly related to the level of knowledge and management, which contribute to the profitability of their business.

Phenotypic characteristics and production traits of chicken

Local chicken were mostly normally feathered (hens 68.1%, cocks 83.3%) with a few showing soft and fluffy feathers (hens 23.9%, cocks 16.7%). Very diverse plumage coloration of neck, breast and wing was observed (Table 6), with pale brown (27%), deep dark brown (27%) and deep dark brown (26.4%), respectively, being the dominant color for these areas in hens. Neck, breast and wing plumage in cocks were predominantly colored in shining orange-yellow (58.3%), black (44.4%) and shining orange-yellow (36.1%), respectively. Most chickens showed very light skin color (hens 75.5%, cocks 38.9%), whereas dark colored skin existed in 21.5% of hens. Yellow and very dark skin were observed at 30.6% each in cocks. The predominant beak color was yellow (hens 64.4%, cocks 41.7%), followed by black to very dark (hens 25.2%, cocks 36.1%) and beige to brown (hens 8.0%, cocks 22.2%). The commonest comb color was red (hens 77.9%, cocks 83.3%), while 4.3% of hens and 16.7% of cocks showed black to very dark red/blue colors. A significant domination (p<0.05) of the single comb in females (74.2%) and males (66.7%) was observed. The predominant iris color was orange/red (hens 74.2%, cocks 55.6%) followed by brown/black (hens 23.9%, cocks 38.9%) and white/yellow (hens 1.8%, cocks 5.6%). The shank color varied between blue-gray (40.5%), white (33.1%), yellow (16.0%) and black (9.2%) in females, and between yellow (36.1%), blue-gray (27.8%), black (25.0%) and white (11.1%) in males.

Table 6.

Color variation in body plumage, skin, beak, iris, shank and comb, and feather and comb type as determined in 199 local chickens across six agro-ecological zones (AEZ) of Oman

| Phenotypic trait | Agro-ecological zones1,2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| MU | BT | NH | EH | EC | DF | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| F (30) | M (6) | F (30) | M (6) | F (30) | M (6) | F (28) | M (6) | F (25) | M (6) | F (20) | M (6) | |

| Neck color | ||||||||||||

| Black | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| White | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Deep dark brown | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Pale brown | 6 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Shining orange-yellow | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Breast color | ||||||||||||

| Black | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| White | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Deep dark brown | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 2 |

| Pale brown | 15 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 2 |

| Shining orange-yellow | 4 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Wing color | ||||||||||||

| Black | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| White | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Deep dark brown | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Pale brown | 13 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| Shining orange-yellow | 3 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Brown/black | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| Body feather type | ||||||||||||

| Normal firm | 28 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 23 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| Many soft and fluffy | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 0 |

| Few, skin showing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Skin color | ||||||||||||

| Yellow | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Very light/pink | 21 | 4 | 22 | 1 | 20 | 2 | 26 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 14 | 1 |

| Very dark/black | 9 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Beak color | ||||||||||||

| Yellow | 17 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 25 | 4 | 17 | 3 | 12 | 0 |

| Beige to light brown | 4 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Black to very dark horn | 9 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Comb color | ||||||||||||

| Red | 26 | 5 | 21 | 4 | 22 | 6 | 23 | 5 | 20 | 6 | 15 | 4 |

| Black to very dark red/blue | 4 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Iris color | ||||||||||||

| White/yellow | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Orange/red | 20 | 4 | 20 | 2 | 22 | 3 | 27 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 13 | 3 |

| Brown/black | 10 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Shank color | ||||||||||||

| Yellow | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| White | 11 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Blue-gray | 14 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Comb type | ||||||||||||

| No comb | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Single | 25 | 4 | 17 | 6 | 19 | 2 | 25 | 3 | 20 | 6 | 15 | 3 |

| Pea | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| V-shape | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Butterfly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Values are numbers of birds per AEZ and sex (F: female; M: male) showing the respective trait.

Agro-ecological zone: Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), Dhofar (DF).

The large variation in plumage color might be attributed to a lack of selection of breeders for this trait, which was also reported from Nigeria (Daikwo et al., 2011), Jordan (Abdelqader et al., 2007) and Botswana (Badubi et al., 2006). Fisseha (2009) suggested that the presence of such large variation in color of plumage and other morphological attributes of chicken ecotypes within regions may be the result of the absence of geographical isolation as well as long periods of natural selection. Light/pink skin and red comb color in females and males dominated in all our study zones, which agree with the findings of Barua and Yoshimur (1997) for local chicken in Bangladesh. The light color of comb and skin might contribute to the birds’ tolerance of heat stress (Van Kampen, 1974; Egahi et al., 2010). From the analysis of 29 autosomal markers it appears that two subspecies of red jungle fowl, namely Gallus gallus gallus from Thailand and Gallus gallus spadicus from China, are quite distant from Omani chicken (Al-Qamashoui et al., 2014a), while analysis of mtDNA indicated that Indian chicken, including subspecies Gallus gallus murghi, seem to be more closely related to the local populations of Omani chicken (Al-Qamashoui et al., 2014b), which can be explained by the historically very intense trade of seafarers from the Arabian Peninsula with the Middle East and Indian region (Biagi, 2006; Boivin and Fuller, 2009).

The mean body weight of local cocks and hens across Oman (1.24 kg) was similar to values from Namibia (Petrus et al., 2011) and central Nigeria (Daikwo et al., 2011), while higher weights were reported from Jordan (Abdelqader et al., 2007) and Botswana (Badubi et al., 2006). At 1.33 ±0.65 kg, the mean body weight (Table 7) of adult cocks was significantly (p<0.05) heavier than that of hens (1.17±0.86 kg). Cocks also had higher values (p<0.05) for body length (18.4±0.14 cm) and shank length (8.1±0.11 cm) than hens (17.3±0.13 cm; 7.1±0.14 cm. While clutch size was not related to body length and shank length of hens (r<0.4, p>0.05), there was a significant correlation between body weight and clutch size (r = 0.66, p<0.05). The differences in body weight and body measures between male and female birds are in agreement with reports from Tanzania (Mwalusanya et al., 2002) and Zimbabwe (Mcainsh et al., 2004); such differences are due to the differential effects of androgens and estrogens on growth (Yakubu et al., 2009). The higher body weight of male and female chickens in DF than in the other AEZ might be attributed to less efforts needed by these birds to scavenge their feed: DF farms are smaller-sized than farms in the other AEZ but characterized by highly productive vegetable cultivation, potentially offering plenty of nutritious residues. Age at sexual maturity of the hen, defined as age when producing the first egg, was reported to be 24.1±1.33 weeks (Table 8), occurring earlier in BT (20.7±1.29) and DF (20.0 ±1.80) than in the other AEZ (p<0.05). Omani hens were maturing at the same pace as hens in Ethiopia (6.7 months; Dessie and Ogle, 2001), and Malawi (6.1 months; Gondwe, 2004). The hens produced on average 5.2±0.23 clutches per year with a total of 12.3±2.85 eggs per clutch (range 8 to 14), resulting in 64.5±6.91 eggs per hen and year. The latter value was higher than that reported for local chicken in Bangladesh (44; Baru and Yoshimur, 1997) and Uganda (40 to 50; Ssewannyana et al., 2008), while it was similar to the production reported from Tanzania (Mwalusanya et al., 2002) and Botswana (Badubi et al., 2006). The proportion of hatched eggs per clutch was 88.1±6.01% with significant differences between EH (92.9±7.16) and the other AEZ (p<0.05). The egg hatchability across Omani smallholder systems is within the range reported from Burkina Faso (60% to 90%; Kondombo et al., 2003) and higher than values reported from Botswana (42%; Badubi et al., 2006) and Nigeria (48%; Daikwo et al., 2011). Hatchability of eggs depends on hygienic and incubation conditions in the nests, egg quality, nutrition of the breeding hen, genetic factors and diseases (Sainsbury, 1992). In our study, the high hatchability might be partly attributed to the high number of breeding cocks per flock. The results of the multiple linear regression analysis (Table 9) indicated that egg production was significantly (p<0.05) higher with increasing years of experience of the chicken owner, old age of the householder and the daily frequency of supplement feeding. In addition to the positive effect of better nutrition on chicken performance, feeding chicken several times a day allows the farmer to observe the flock and notice any problem. Since a quantification of chickens’ daily feed intake was not feasible in the context of the present study, it was also not possible to relate the observed variation in body conformation and production traits to differences in feeding management.

Table 7.

Body weight, body and shank lengths (means1±SD) of 199 local chickens across six agro-ecological zones2 of Oman

| Agro-ecological zone | Birds (n) | Body weight (kg) | Body length (cm) | Shank length (cm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| MU | 6 | 30 | 1.4±0.29 | 1.1±0.09 | 18.3±0.11 | 17.5±0.13 | 8.5±0.22 | 6.9±0.13 |

| BT | 6 | 30 | 1.3±0.15 | 1.2±0.10 | 18.7±0.21 | 17.5±0.09 | 8.2±0.17 | 6.9±0.14 |

| NH | 6 | 30 | 1.3±0.42 | 1.2±0.11 | 18.5±0.19 | 17.0±0.13 | 8.5±0.22 | 6.9±0.14 |

| EH | 6 | 28 | 1.2a±0.41 | 1.0±0.09 | 18.3±0.17 | 17.6±0.20 | 8.3±0.21 | 6.8±0.16 |

| EC | 6 | 25 | 1.4±0.37 | 1.1±0.10 | 17.2±0.17 | 16.8a±0.11 | 7.7±0.33 | 7.2±0.13 |

| DF | 6 | 20 | 1.4±0.14 | 1.4a±0.28 | 18.8±0.17 | 18.2±0.14 | 8.0±0.36 | 8.1a±0.16 |

Within columns (i.e., between agro-ecological zones) values with a superscript differ at p<0.05 from the others (Kruskal-Wallis test).

Agro-ecological zone: Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), Dhofar (DF).

Table 8.

Flock size and performance traits (means1±SD) of local chickens as given by 163 smallholder farmers across six agro-ecological zones2 of Oman

| Variable | MU n = 30 |

BT n = 30 |

NH n = 30 |

EH n = 28 |

EC n = 25 |

DF n = 20 |

Overall mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken per flock (n) | 23.7±9.33 | 28.7±7.65 | 25.6±8.35 | 23.2±8.70 | 14.6±2.10 | 25.7±7.64 | 21.9±7.69 |

| Age at first egg laying (wk) | 26.6±3.72 | 20.7±3.44 | 24.3±4.32 | 26.2±1.10 | 27.0±2.65 | 20.0±1.21 | 24.1±1.33 |

| Clutch size (eggs) | 11.4±3.33 | 13.2±3.33 | 13.1±2.05 | 13.0±2.00 | 10.1±1.16 | 13.2±1.97 | 12.3±2.85 |

| Clutches per year (n) | 5.2±0.12 | 5.0±0.41 | 4.8±0.22 | 6.0±0.48 | 5.3±0.27 | 5.1±0.45 | 5.2±0.23 |

| Yearly egg production (n/hen) | 59.3±7.24 | 66.0±10.05 | 62.9±6.66 | 78.0±6.61 | 53.5±7.21 | 67.3±5.71 | 64.5±6.91 |

| Yearly hatchability (% eggs per hen) | 86.5a±4.65 | 87.8ab±5.77 | 89.5ab±5.90 | 92.9b±7.16 | 85.4ab±5.64 | 86.5a±6.11 | 88.1±6.01 |

| Male : female ratio (m/10 f) | 2.4±0.86 | 2.4±1.08 | 2.2±1.01 | 2.3±1.02 | 1.9±0.93 | 2.0±0.90 | 2.1±0.92 |

| Yearly mortality rate in flock (%) | 15.6a ±1.66 | 16.6abc±1.17 | 15.8a±1.76 | 16.2abc±1.96 | 16.9bc±0.73 | 17.0c±1.21 | 16.3±1.37 |

Within rows, means with different superscripts differ at p<0.05 between agro-ecological zones (Kruskal-Wallis test).

Agro-ecological zone: Musandam (MU), Batinah (BT), North Hajar (NH), East Hajar (EH), East Coast (EC), Dhofar (DF).

Table 9.

Coefficients of the multiple linear regressions predicting yearly chicken flock size, total egg production and yearly survival rates for local chickens of 163 smallholder farmers across six different agro-ecological zones of Oman

| Regression coefficients | b | SEb | t-value2 | Partial R2 | p≤ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Chicken flock size | |||||

| Constant a (and SEa) | 4.57 | 2.08 | −0.21 | - | 0.030 |

| Family size (n) | 0.38 | 0.13 | 2.89 | 0.15 | 0.004 |

| Gender of chicken owner (female = 1, male = 0) | 6.88 | 0.97 | 7.05 | 0.41 | 0.001 |

| Total livestock (TLU1) | 0.46 | 0.11 | 4.27 | 0.23 | 0.001 |

| Using a solid house (1 = yes) | 3.99 | 1.20 | 3.31 | 0.21 | 0.001 |

| Management assets used (n) | 0.80 | 0.42 | 1.90 | 0.12 | 0.059 |

| Overall R2 | 0.64 | 0.001 | |||

| Dependent variable: Total egg production per hen (eggs/yr) | |||||

| Constant a (and SEa) | 13.37 | 4.01 | 3.34 | - | 0.001 |

| Experience in chicken keeping (years) | 2.90 | 0.23 | 12.88 | 0.70 | 0.001 |

| Age of householder (1, >70 years) | 3.27 | 1.68 | 1.95 | 0.11 | 0.053 |

| Using a solid-stable house (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −6.10 | 2.22 | −2.74 | −0.17 | 0.007 |

| Frequency of supplement feeding per day (n) | 2.09 | 1.00 | 1.88 | 0.90 | 0.038 |

| Chicken flock size (n) | 0.22 | 0.11 | 2.09 | 0.11 | 0.050 |

| Overall R2 | 0.58 | 0.001 | |||

| Dependent variable: Yearly survival rate of birds (%) | |||||

| Constant a (and SEa) | 81.91 | 0.32 | 254.4 | - | 0.001 |

| Existence of hired laborers (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.87 | 0.40 | 2.16 | 0.12 | 0.032 |

| Age of householder (1, >70 years) | −0.75 | 0.39 | −1.90 | −0.10 | 0.059 |

| Administration of medicine (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 6.02 | 0.45 | 13.31 | 0.71 | 0.001 |

| Overall R2 | 0.60 | 0.001 | |||

TLU: Tropical livestock unit, hypothetical animal of 250 kg live weight. Conversion factors used: cattle = 0.80, sheep and goats = 0.10, donkey = 0.5, chicken = 0.01.

t-value: A high absolute t value suggests that a predictor variable is having a large impact on the dependent variable.

Yearly bird mortality (total number of birds that died divided by average yearly flock size) was 16.4±1.37% with the highest percentage (p<0.05) reported from DF (17.0 ±1.21%). Lack of adequate housing can partly explain the mortality, as good housing is a prerequisite for any viable and sustainable chicken operation (Fisseha, 2009). The multiple linear regression analysis indicated that the yearly survival rate of the chicken depended on the provision of medicine and health treatments to the chicken, and was in addition positively affected by hiring external labor, but negatively related to old age of the householder (Table 9). The latter seems to indicate that management intensity declines with advanced age of the farmer, which might be due to poor willingness of elderly persons to take risk in overall farm management (Mandleni and Anim, 2012).

Average flock size across all AEZ, calculated as mean of the current size and the maximum and minimum flock size during the past 10 years, was 21.9±7.69 birds and varied between 12 and 41 (Table 8). Flock size in EC (14.6±2.10) was lowest (p<0.05) whereas it was highest in BT (28.7±7.65). At least one cock was kept in each flock for breeding purposes. The average sex ratio was 2.1±0.92 cocks per 10 females. The present chicken flock size was in the range of values reported from northern Ethiopia (12; Fisseha, 2009), and Uganda (18; Ssewannyana et al., 2008). Larger flock sizes were reported from Mauritius (60; Jugessur et al., 2006), Jordan (41; Abdelqader et al., 2007) and Burkina Faso (34; Kondombo et al., 2003). The results of the multiple linear regression analysis (Table 9) showed that family size, female gender, total livestock numbers (in Tropical Livestock Units (TLU): hypothetical animal of 250 kg live weight. Conversion factors used: cattle = 0.80, sheep and goats = 0.10, donkey = 0.5, chicken = 0.01), availability of a solid chicken house and the number of management assets used had a positive and significant influence on chicken flock size (p<0.05). The effect of family size on flock size might be explained by the importance of the chicken as an easy source of food for family needs. Mandleni and Anim (2012) stated that a larger family is more inclined to keep more livestock and chickens than a smaller family. Gueye (2000) suggested that poultry, by its proximity to the homestead, is an obvious enterprise for women. The positive effect of female ownership on chicken flock size may be explained by the regular provision with leftovers of family meals which are mostly collected by women. The role of rural women in chicken husbandry and the important contribution of chickens to the livelihoods of rural households have been highlighted in several studies (Mapiye et al., 2008; Fisseha, 2009). Thus, strategies for improving chicken productivity should consider women as the entry point and actively involve them in measures of improvement and conservation of traditional poultry breeds (Dessie and Ogle, 2001).

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATION

Across Oman’s different agro-ecological zones, rural chickens are exposed to insufficient feeding and housing, leading to a low productivity of laying hens. Since proper housing and cleaning, supplement feeding and health care substantially improve chicken performance, such measures must be promoted through training and extension programs. Given that chicken ownership, care and decision-making is largely in the hands of rural women, they have to be involved in development and conservation programs for local chickens in Oman. In view of the high variation in phenotypic and morphometric traits of regional chicken populations, any conservation program must be preceded by a comprehensive study of the genetic diversity of these populations so as to determine whether phenotypic dissimilarity is underpinned by genetic variation that can be deployed for such endeavors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to the farmers who participated in our study, and to the members of Agricultural Directorates and Research Centers for providing farmer names and coordinating the field visits. Financial support for this study was provided by Sultan Qaboos University Muscat, Oman, through the Department of Animal and Veterinary Science (HM Fund SR/AGR/ANVS/08/01).

REFERENCES

- Al-Qamashoui B, Simianer H, Kadim I, Weigend S. Assessment of genetic diversity and conservation priority of Omani local chickens using microsatellite markers. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2014a doi: 10.1007/s11250-014-0558-9. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qamashoui B, Al-Ansari A, Simianer H, Weigend S, Mahgoub O, Costa V, Weigend A, Al-Araimi N, Beja-Pereira A. From India to Africa across Arabia: An mtDNA assessment of the origins and dispersal of chicken around the Indian Ocean Rim. BMC Genetics. 2014b Submitted in Feb. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelqader A, Wollny CB, Gauly M. Characterization of local chicken production systems and their potential under different levels of management practices in Jordan. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2007;39:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s11250-007-9000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo O, Adeola R. Socio-economic factors affecting poultry farmers in Ejigbo local government area of Osun State. J Hum Ecol. 2005;18:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Aini I. Indigenous chicken production in South-East Asia. World Poult Sci J. 1990;46:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Archer KJ, Lemeshow S. Goodness-of-fit test for a logistic regression model fitted using survey sample data. Stata J. 2006;6:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Badubi SS, Rakereng M, Marumo M. Morphological characteristics and feed resources available for indigenous chickens in Botswana. [Accessed Mar. 2012];Livest Res Rural Dev. 2006 18(3) http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd18/1/badu18003.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Barua A, Yoshimur Y. Rural poultry keeping in Bangladesh. World Poult Sci J. 1997;53:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi P. The shell-middens of the Arabian Sea and Persian Gulf: Maritime connections in the 7th Millennium BP. Adumatu. 2006;14:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin N, Fuller DQ. Shell middens, ships and seeds: Exploring coastal subsistence, maritime trade and the dispersal of domesticates in and around the ancient Arabian Peninsula. J World Prehistory. 2009;22:113–180. [Google Scholar]

- Daikwo I, Okpe A, Ocheja J. Phenotypic characterization of local chicken in Dekina. Int J Poult Sci. 2011;10:444–447. [Google Scholar]

- Dessie T, Ogle B. Village poultry production systems in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2001;33:521–537. doi: 10.1023/a:1012740832558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egahi J, Dim N, Momoh O, Gwaza D. Variations in qualitative traits in the Nigerian local chicken. Int J Poult Sci. 2010;10:978–979. [Google Scholar]

- Fisseha M. MSc thesis. Hawassa University; Ethiopia: 2009. Studies on Production and Marketing Systems of Local Chicken Ecotypes in Bure Woreda, North-west Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Gondwe T. PhD thesis. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen; Germany: 2004. Characterization of Local Chicken in Low Input-low Output Production Systems: Is There Scope for Appropriate Production and Breeding Strategies in Malawi? [Google Scholar]

- Gueye E. Women and family poultry production in Africa. Dev Pract. 2000;10:98–102. doi: 10.1080/09614520052565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black B, Babin B, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate Data Analysis. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ USA: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hall HTB. Diseases and Parasites of Livestock in the Tropics. 2nd ed. Longman Group Ltd.; Harlow, Essex, UK: 1986. p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- Jens R, Anders P, Charlotte V, Ainsh M, Lone F. Keeping Village Poultry: A Technical Manual for Small-scale Poultry Production. Copenhagen, Denmark: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jugessur V, Pillay M, Ramnauth R, Allas M. Improving Farmyard Poultry Production in Africa: Interventions and Their Economic Assessment. Vienna: IAEA-TECDOC-1489; 2006. The socio-economic importance of family poultry production in the republic of Mauritius; pp. 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kondombo S, Nianogo A, Kwakkel R, Udo H, Slingerland M. Comparative analysis of village chicken production in two farming systems in Burkina Faso. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2003;35:563–574. doi: 10.1023/a:1027336610764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandleni B, Anim F. Climate change and adaptation of small-scale cattle and sheep farmers. Afr J Agric Res. 2012;7:2639–2646. [Google Scholar]

- Mapiye C, Mwale M, Mupangwa J, Chimonyo M, Foti R, Mutenje M. A research review of village chicken production constraints and opportunities in Zimbabwe. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2008;21:1680–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Mcainsh C, Kusina J, Madsen J, Nyoni O. Traditional chicken production in Zimbabwe. World Poult Sci J. 2004;60:233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MOAF) Agricultural Annual Report. Muscat, Oman: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of National Economy (MONE) Data and indicators of the population. Muscat, Oman: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mwalusanya N, Katule A, Mutayoba S, Mtambo M, Olsenand J, Minga U. Productivity of local chicken under village management conditions. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2002;34:405–416. doi: 10.1023/a:1020048327158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrus N, Mpofu I, Lutaaya E. The care and management of indigenous chicken in Northern communal areas of Namibia. [Accessed Mar. 2012];Livest Res Rural Dev. 2011 23(12) http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd23/12/petr23253.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlah A. Performance of village fowl in Malaysia. World Poult Sci J. 1996;52:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury D. Poultry health and management - chicken, turkeys, ducks, geese, quail. 3rd ed. Blackwell Scientific Ltd; Oxford, UK: 1992. p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Ssewannyana E, Ssali A, Kasadha T, Dhikusooka M, Kasoma P, Kalema J, Kwatotyo B, Aziku L. On-farm characterization of indigenous chicken in Uganda. J Anim Plant Sci. 2008;1:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kampen M. Physical factors affecting energy expenditure. In: Morris TR, Freeman BM, editors. Energy Requirements of Poultry. Longman Group Ltd: Edinburgh, UK: 1974. pp. 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu A, Kuje D, Okpeku M. Principal components as measures of size and shape in Nigerian indigenous chicken. Thai J Agric Sci. 2009;42:167–176. [Google Scholar]