Abstract

Forty two Malpura lambs (21 d old) were divided into three groups of 14 each consisting of 8 females and 6 males. Lambs were allowed to suckle their respective dams twice daily up to weaning (13 wks) and offered free choice concentrate and roughage in a cafeteria system. The lambs in control group were fed conventional concentrate mixture, in RBO group concentrate mixture fortified with 4% industrial grade rice bran oil and in Ca-soap rice bran oil (as in RBO group) was supplemented in the form of calcium soap. The concentrate intake decreased(p≤0.05) in RBO group as a result total dry matter, crude protein and metabolizable energy intake decreased compared to control whereas Ca-soap prepared from the same rice bran oil stimulated the concentrate intake leading to higher total dry matter, crude protein and energy intakes. The digestibility of dry matter (p≤0.05), organic matter (p≤0.05) and crude protein (p≤0.05) was higher in RBO group followed by Ca-soap and control whereas no effect was observed for ether extract digestibility. Higher cholesterol (p≤0.05) content was recorded in serum of oil supplemented groups (RBO and Ca-soap) while no effect was recorded for other blood parameters. Rice bran oil as such adversely affected and reduced the body weight gain (p≤0.001) of lambs in comparison to control whereas the Ca-soap of rice bran oil improved body weight gain and feed conversion efficiency in lambs. Fat supplementation decreased total volatile fatty acids (p≤0.05) and individual volatile fatty acid concentration which increased at 4 h post feeding. Fat supplementation also reduced (p≤0.05) total protozoa count. Ca-soap of rice bran oil improved pre slaughter weight (p≤0.05) and hot carcass weight (p≤0.05). It is concluded from the study that rice bran oil in the form of calcium soap at 40 g/kg of concentrate improved growth, feed conversion efficiency and carcass quality as compared to rice bran oil as such and control groups.

Keywords: Rice Bran Oil, Ca-soap, Total Volatile Fatty Acid, Growth, Carcass Trait, Digestibility

INTRODUCTION

Under traditional feeding practices on grazing resources alone, lambs achieve only 40 to 50 g average daily gain during active phase of growth and attain market weight of 20 to 22 kg at 9 to 12 months of age (Karim and Bhatt, 2012). Lambs require high energy to support faster growth (Manso et al., 2006; Bhatt et al., 2009). Feeding higher level of concentrate to lambs increased feed intake and live weight gain (Santra and Karim, 2002). It is presumed that fortification of concentrate with fat supplementation would increase energy content and improve growth at similar intake levels. Inclusion of fat in ruminant diets improves energy efficiency due to direct use of long chain fatty acids in the metabolic pathways of fat synthesis without the need for acetate and glucose (Clinquart et al., 1995; Machmuller et al., 2000). Further, it has been observed that additions of fat prevent ruminal acidosis, facilitate absorption of liposoluble nutrients thus rendering it possible to modify meat according to consumer demand (Perez et al., 2002). Inclusion of fat as energy source in proper form is prerequisite for improving pre and post-weaning growth. Bhatt et al. (2011) reported that inclusion of coconut oil at high (>5%) level in the diet decreased concentrate intake. It has been observed that calcium salt of fatty acids (Ca-FA) at 0, 2, 4, or 6 % to finisher beef diets increased neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) digestibility (Nigdi et al., 1990). The present experiment was therefore planned to study the effect of rice bran oil as such or as calcium salt (rumen protected fat) supplementation on growth performance, nutrient intake and utilization, blood metabolites and carcass composition in Malpura lambs.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The experiment was carried out at the Central Sheep and Wool Research Institute, Avikanagar, Rajasthan, India located at 26° 17′N latitude and 75° 28′E longitude and 320 m above mean sea level. The climate is typical hot and semi-arid. The study was initiated in November 2009 and ended in April 2010. During the experiment, minimum and maximum ambient temperature ranged from 6.87 to 24.67°C and 23.52 to 41.53°C and relative humidity varied from 14.83 to 83.42%. The animal care, handling and sampling procedures were approved by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiment on Animal (CPCSEA), India.

Animal and feeding management

Forty two Malpura lambs (21 d old) were divided into three equal groups consisting of 8 females and 6 males. Up to weaning age (90 d), lambs were housed with their dams during night and penned in well ventilated enclosure during the day in groups. In addition to free suckling, the lambs were offered ad libitum concentrate and roughage (Prosopis cineraria leaves) in separate feeders. The experiment continued up to six month of age of lambs. The lambs in control group were fed conventional concentrate mixture, in RBO group concentrate mixture fortified with 4% industrial grade rice bran oil whereas in Ca-soap group concentrate supplemented with rice bran oil converted into calcium salt of fatty acids by modified method of Naik et al. (2007). The process involved anhydrous calcium hydroxide (40% of the amount of oil to be treated) dissolved in 15 times tap water mixed with warm oil and sulfuric acid (3% of the amount of oil dissolved in five times tap water) stirred for 25 min on flame, filtered through muslin cloth, washed and dried. The prepared Ca-soap consists of 63% oil and 37% mineral. Daily roughage and concentrate mixture intake were recorded during entire experiment period.

During post weaning (90 to 180 d), lambs were weaned and kept in separate enclosures and offered ad libitum concentrate and roughage (Prosopis cineraria leaves) in cafeteria system. They were let loose in open from 7.00 to 9.00 am in the morning and 4.00 to 6.00 pm in the evening hours. Water was made available at free choice to lambs during entire period of experiment. Daily records of concentrate and roughage intake were maintained. Metabolizable energy intake (MEI) was calculated according to ARC (1990) as: MEI (MJ/kg DM) = ((digestible OM, g/kg DM)/1,000)×18.5×0.81.

Growth trial

Daily feed intake and weekly body weights (BW) were recorded during pre weaning (21 to 90 d) and post weaning (91 to 180 d) period.

Sample collection and digestibility trial

Roughage and concentrate samples were collected once a week and respective samples of different weeks mixed thoroughly and pooled after drying for chemical analysis. Metabolic trial with four male lambs in each treatment was conducted during post weaning stage at 150 d of age. Lambs were kept in metabolic cages for ten days with five days adaptation and five days collection period. Concentrate and roughage offered, residue left, feces voided and urine excreted were weighed, recorded and preserved for later chemical analysis. The samples of concentrate, roughage, and feces were dried in forced air oven at 70°C till constant weight for dry matter determination. Samples were ground to pass a 1 mm screen and preserved for chemical analysis.

Hematological and serum biochemical profile

At 180 (post weaning) days of age, 5 ml of blood was collected into 10 ml sterilized syringes by jugular vein puncture from five male lambs of each treatment before morning feeding. Serum was separated after 3 h of incubation at 37°C. Immediately after the serum collection, glucose was estimated by Glucose oxidase-glucose peroxidase (GOD-POD) method (Trinder, 1969). Serum samples were preserved in polypropylene vials at −20°C for later estimation of cholesterol (Wybenga et al., 1970) and free fatty acids (Shipe et al., 1980).

Lamb slaughter

At six month of age, all the male lambs were shorn manually and slaughtered following standard procedures for carcass evaluation (ISI, 1963). The weight of digestive contents was obtained from difference between full and empty digestive tract and empty live weight was computed as the difference between slaughter weight and weight of digestive contents. Loin eye area (cm2) was recorded on the cut surface of Longissimus dorsi muscle at the interface of 12th and 13th rib on both side of the carcass. Samples of Longissimus dorsi muscle were collected for estimation of chemical composition.

Chemical analysis

All the samples of feed, feces, urine and muscle samples were analyzed for chemical composition as per standard AOAC (2000) methods. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was determined without sodium sulphite or α-amylase, whereas acid detergent fiber (ADF) and acid detergent lignin (ADL) was expressed inclusive of residual ash and lignin was determined by solubilization of cellulose with sulphuric acid as per Van Soest et al. (1991).

Rumen fermentation characteristics and ciliate protozoa count

During post weaning phase (at 180 d of age) rumen liquor (50 ml) samples were withdrawn using a stomach tube and suction pump from six intact lambs of each treatment at 0 and 4 h post feeding. Samples were placed in a 100 ml glass jar for pH determination using a portable pH meter within 4 to 5 min of sampling. After pH measurement rumen fluid was strained with four layer of muslin cloth. Strained rumen liquor (SRL) samples were preserved after adding a few drops of saturated mercuric chloride solution and stored in labeled polypropylene bottles at −20°C till further analysis. The SRL samples were analyzed for individual and total volatile fatty acids with DANI make Gas Chromatograph (Model 1000, Series 011124002, DANI, Cologno, Monzese Italy) using flame ionizing detector (FID), programmable temperature vaporizer (PTV) injector and capillary column (SP-Packed column 10% SP-1000, 2 mm length ). Ciliate protozoa numbers in SRL were counted following the procedure of Sahoo et al. (1999).

Statistical analysis

Data were subjected to one way analysis of variance using SPSS Base 14.0 (SPSS Software products, Marketing Department, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL 60606-6307, USA), using mathematical model:

Where Yijk = observation mean; μ = general mean, Ti = effect of ith dietary treatment (i = 1, 2, 3), eij = random error. Significance among mean values for three dietary treatments was tested using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (Duncan, 1955). The data for rumen metabolites was analyzed for treatment×collection hour interaction using factorial design. Weekly BW change of individual lamb was used for fitting polynomial curves and the generation of equation in Figure 1.

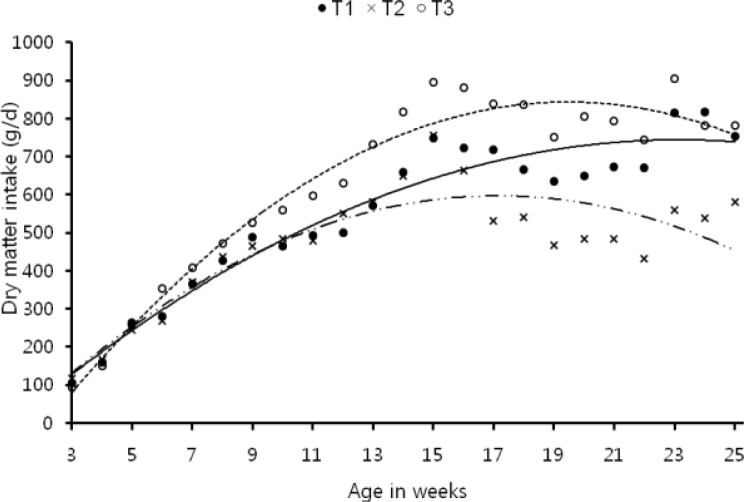

Figure 1.

Pattern of daily dry matter intake during different weeks in different treatments. T1 -•- (control): y = −1.516x2+70.25x−69.4 (R2 = 0.933). T2 -··×-·· (control+40 g rice bran oil/kg): y = −2.329x2+79.88x−87.57 (R2 = 0.779). T3 ··○·· (control+ca-soap of rice bran oil 40 g/kg): y = −2.815x2+109.6x−223.2 (R2 = 0.956).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemical composition and plane of nutrition

Ether extract increased in both the test diet whereas total ash contents increased in diet fortified with Ca-soap (Table 1). The addition of fat increased ether extract of lamb’s diet in T2 and T3 groups and no effect on other nutrients was recorded.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (g/kg) of experimental diets

| Nutrients | Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | SEM | Prosopis cinereria leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter | 961 | 958 | 955 | 4.52 | 956±7.11 |

| Organic matter | 934 | 936 | 929 | 1.31 | 897±6.23 |

| Crude protein | 187 | 178 | 173 | 6.94 | 119±1.97 |

| Ether extract* | 40a | 77.7b | 74.0b | 4.95 | 38.0±0.61 |

| Total ash | 65.4 | 63.6 | 70.9 | 2.74 | 103±1.21 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 505 | 484 | 482 | 24.3 | 617±4.14 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 109 | 104 | 105 | 21.3 | 50.3±0.71 |

| Hemi-cellulose | 397 | 380 | 377 | 18.4 | 114±1.12 |

| Cellulose | 79.0 | 76.7 | 79.6 | 15.3 | 294±3.42 |

| Lignin | 29.5 | 27.4 | 25.2 | 4.11 | 209±1.72 |

Different superscripts show significant (p<0.05) differences between diets. RBO: Rice bran oil. Ca-soap: Calcium soap made of rice bran oil.

SEM = Standard error of mean. The concentrate mixture in control (T1) group consisted of maize-300, barley 300, groundnut cake 200, til cake 120, molasses 50, mineral mixture 20, common salt 10 g/kg of feed.

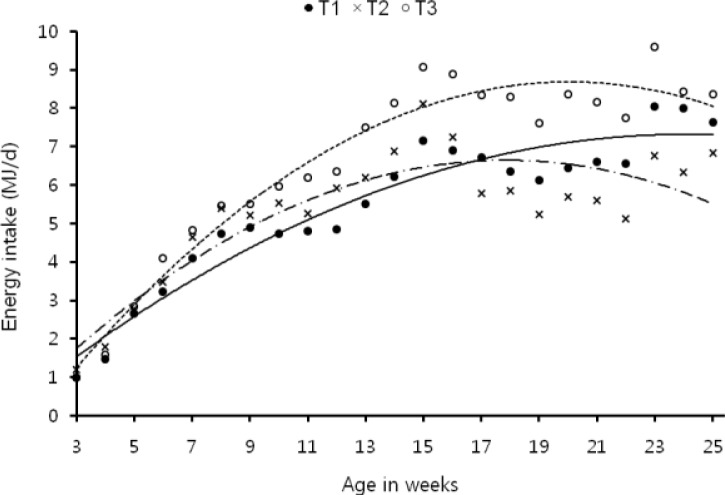

Plane of nutrition revealed differences in roughage: concentrate ratio, daily concentrate, total dry matter, crude protein, organic matter, digestible organic matter, digestible crude protein and ME intakes between control and test groups (Table 2). The supplementation of industrial grade rice bran oil decreased concentrate intake (p≤0.05) as a result total dry matter and nutrient intakes also reduced. Ca-soap prepared from the same oil stimulated concentrate intake thus increased total dry matter, protein and energy intakes as compared to control. In Ca-soap group, daily dry matter intake increased after five weeks of age whereas in rice bran oil group the dry matter intake was lower and at par with control up to eleven weeks of age and there after it decreased (Figure 1). Similarly daily ME intake remained higher in Ca-soap supplemented group throughout the experiment whereas in rice bran oil supplemented group it was higher up to 15th week of age and after that it decreased (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Plane of nutrition of lambs fed control and test diets

| Parameter | Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrate intake (g/d) | 550.2b | 471.7a | 635.6c | 35.7 |

| Roughage intake (g/d) | 104.0 | 106.3 | 101.4 | 6.8 |

| Total dry matter intake (g/d) | 654.1b | 577.9a | 735.7c | 36.2 |

| Roughage: Concentrate ratio | 0.196a | 0.228b | 0.175a | 0.11 |

| Crude protein intake (g/d) | 115.1b | 96.6a | 122.0b | 5.76 |

| Organic matter intake (g/d) | 514.2b | 435.9a | 590.1c | 32.1 |

| Digestible organic matter intake (g/d) | 362.1a | 356.4a | 442.0b | 25.2 |

| Digestible crude protein intake (g/d) | 60.4a | 59.4a | 79.2b | 3.9 |

| Metabolizable energy intake (MJ/d) | 5.42a | 5.34a | 6.62b | 0.31 |

RBO = Rice bran oil. Ca-soap = Calcium soap made of rice bran oil. MJ = Mega joule. SEM = Standard error of mean. Values wearing different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Pattern of energy intake during different weeks in different treatments. T1 -•- (control): y = −0.013x2+0.627x−0.229 (R2 = 0.917). T2 -··×-·· (control+rice bran oil 40 g/kg): y = −0.022x2+0.792x−0.427 (R2 = 0.769). T3 ··○·· (control+ca-soap of rice bran oil 40/kg): y = −0.025x2+1.025x−1.594 (R2 = 0.945).

Higher concentrate intake increased ME intake of lambs in Ca-soap supplemented group. Reduced heat energy as a result of lower microbial fermentation and less energy loss by calcium soap may be the other reason for higher ME intake of lambs in Ca-soap group. Similar findings were reported by Bhatt et al. (2012) in lambs fed different levels of rumen bypass fat. Poor intake of concentrate mixture containing RB oil reduced the dry matter intake. Similar observations were also reported earlier by Bhatt et al. (2011) in lambs fed different levels of coconut oil. Haddad and Younis (2004) also reported decrease DM intake with addition of 25 and 50 g/kg of saturated fat in the diets of Awassi lambs. Machmüller and Kreuzer (1999) concluded from the study that inclusion of coconut oil at higher level decrease the palatability of diet. The effects of dietary fat on reduction of feed intake is a complex mechanism and involves effects of fatty acids on gut peptides and pancreatic hormones along with direct/indirect effects on hepatic energy oxidation (Allen et al., 2009). Moreover, the extent of DMI depression by dietary fat related to unsaturated FA concentration and effect was found greater for free FA compared to triglycerides (Jenkins and Palmquist, 1984). Reduced concentrate intake decreased the crude protein intake in RB oil supplemented group whereas it increased organic matter and crude protein digestibility improved DCP and ME intake which made it comparable with control group. Reddy et al. (2003) also reported no effect of inclusion of saturated fat up to 15% level on DCP value of sheep ration.

Digestibility and nitrogen balance

Dry matter, organic matter, crude protein and ether extract intakes of lamb during metabolic trial followed the similar trend as recorded during growth study: the values were lower in rice bran oil and higher in Ca-soap supplemented group than the control (Table 3). The digestibility of dry matter, organic matter and crude protein were higher in rice bran oil (T2) followed by Ca-soap supplemented group (T3) and control (T3) where as no effect was observed for ether extract digestibility. Nitrogen balance showed higher N intake (p≤0.05) in Ca-soap supplemented group followed by control and rice bran oil. Excretion of N through feces was higher (p≤0.05) in control as compared to test groups. Nitrogen retained per day was higher in Ca-soap followed by control and lowest in rice bran oil supplemented group and the differences were significant (p≤0.05) between Ca- soap and control group with RBO group.

Table 3.

Intake, digestibility (g/kg) and Nitrogen balance in lambs fed control and test diet

| Parameter | Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter intake (g/d) | 744b | 582a | 799b | 44.5 |

| Dry matter digestibility (g/kg) | 571a | 646b | 616a | 13.2 |

| Organic matter intake (g/d) | 700b | 552a | 751b | 44.5 |

| Organic matter digestibility (g/kg) | 596a | 671b | 649a | 13.9 |

| Crude protein intake (g/d) | 112b | 80a | 115b | 7.54 |

| CP digestibility (g/kg) | 524a | 614b | 565a | 18.9 |

| Ether extract intake (g/d) | 36.4a | 39.1a | 55.8b | 3.66 |

| Ether extract digestibility (g/kg) | 679 | 694 | 699 | 22.0 |

| Nitrogen balance | ||||

| N intake (g/d) | 17.9b | 12.8a | 18.4b | 1.20 |

| N excretion in feces (g/d) | 8.52b | 5.13a | 6.73a | 0.62 |

| N excretion in urine (g/d) | 2.97 | 2.88 | 3.92 | 0.25 |

| N balance (g/d) | 6.43b | 4.84a | 7.75b | 0.65 |

RBO = Rice bran oil. Ca-soap = Calcium soap made of rice bran oil. SEM: Standard error of mean. Values wearing different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p<0.05).

The increased digestibility of dry matter, organic matter and crude protein in fat supplemented group compared well with the results of Yusuf et al. (2009) and Wanapat et al. (2005) who reported increased digestibility with supplementation of sheabutter fat and coconut oil in sheep ration. The increased organic matter digestibility in RBO supplemented group was due to higher CP and EE digestibility. Similar observations were also made by Reddy et al. (2003) and Alexander et al. (2002). Wu et al. (1991) reported higher digestion of fatty acids in calcium soap owing to lower ruminal bio hydrogenation and subsequently higher levels of unsaturated fatty acids in intestinal chime. Reduced nitrogen intake/d in RB oil fed group depressed the daily nitrogen balance. Dietary fat stimulates intestinal cholesterol synthesis (Nestel et al., 1978) to meet the growing demand of absorption and transport of fat which may explain our results. Bindel et al. (2000), Febel et al. (2002) and Khorasani and Kennelly (1998) also reported increased cholesterol and free fatty acid level in serum by fat supplementation.

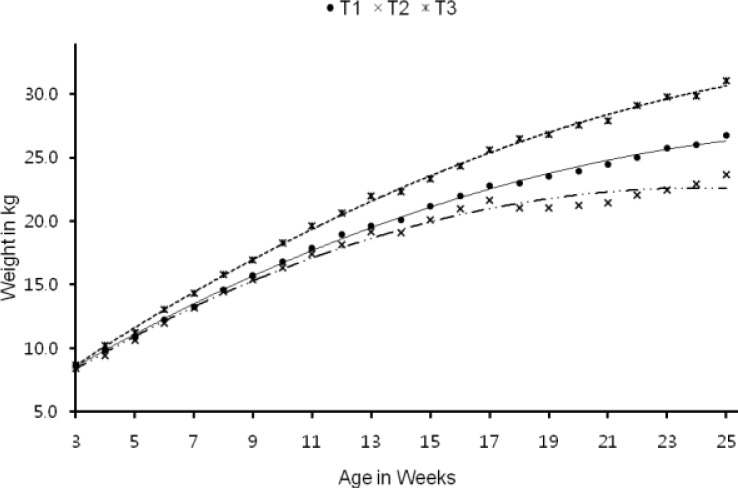

Growth performance and blood biochemical

The highest six month weight (p<0.001), gain in weight (p<0.001) and average daily gain (p<0.001) were recorded in Ca-soap supplemented group followed by control and rice bran oil supplemented group (Table 4). Weekly body weight revealed superior growth in Ca-soap from the beginning whereas with rice bran oil the growth was comparable with control up to 7 wks and thereafter it gradually decreased up to finishing stage (Figure 3). Feed: gain ratio (DMI (kg)/weight gain (kg)) was superior in Ca-soap and feed conversion efficiency deteriorated in rice bran oil supplemented group compared with control and the differences were significant (p≤0.05) between groups. Blood biochemical profile revealed higher (p≤0.05) cholesterol values in test diets as compared to control.

Table 4.

Growth performance and blood biochemical of lambs in different treatments

| Parameter | Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial BW (kg) | 8.65 | 8.42 | 8.71 | 0.45 |

| 6 Month weight (kg) | 26.87b | 23.60a | 31.14c | 0.72 |

| Gain in weight (kg) | 18.22b | 15.18a | 22.43c | 0.67 |

| ADG (g) | 110.4b | 91.97a | 135.91c | 4.07 |

| DMI (g/d) | 588.8b | 520.2a | 662.1c | 40.5 |

| Feed:gain ratio | 5.35b | 6.02c | 4.95a | 0.146 |

| Blood biochemical | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 40.9 | 44.6 | 43.6 | 1.901 |

| Cholesterol (mg/100 ml) | 55.2a | 73.7b | 77.9b | 2.876 |

| Non-esterified fatty acids (meq/L) | 20.0 | 19.2 | 24.5 | 1.015 |

RBO = Rice bran oil. Ca-soap = Calcium soap made of rice bran oil. SEM = Standard error of mean.

ADG = Average daily gain. DMI = Dry matter intake. Values wearing different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Body weight change of lambs in different treatments experimental lambs. T1 -•- (control): y = −0.023x2+1.477x+4.319 (R2 = 0.998), T2 -··×-·· (control+40 g RBO/kg)): y = −0.031x2+1.537x+4.039 (R2 = 0.0.989), T3 ··○·· (control+ca-soap of rice bran oil 40 g/kg): y = −0.024x2+1.681x+3.828 (R2 = 0.972).

The growth performance of lambs corroborated well with the nutrient intake, its utilization and nitrogen balance. Lourenco et al. (2000) also reported high correlation of intake of digestible OM with ADG of lambs which was also observed in this experiment. Improved feed palatability by Ca-soap supplementation in present study was similar to the findings of Sklan et al. (1990) reporting increased metabolizable energy intake, improved weight gain and FCR. Supplementation of oil improved rumen fermentation in terms of the fermentation end products (Wanapat et al., 2005) and also eliminated the protozoa from the rumen of cattle and sheep to improve growth rate with concomitant increases in bacterial population and microbial protein flow from the rumen (Leng, 1989; Santra et al., 2007). In spite of this fact, nutrient intake, growth and feed conversion efficiency did not improve in present study in RB oil supplemented group.

Rumen metabolite

Rumen metabolite revealed treatment effect for total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acids, holotrichs, spirotrichs and total protozoal population (Table 5). The rice bran oil as such and as Ca-soap decreased TVFA as well as individual fatty acids. At 4 h post feeding there was increase in TVFA, acetic acid, propionic acid value in Ca-soap diet whereas in rice bran oil diet there was decrease in acetic acid value when compared with 0 h values. Population of protozoa was also decreased (p≤0.05) with rice bran oil as such or as Ca-soap as compared to control.

Table 5.

Rumen fermentation characteristics in lambs fed control and test diet

| Parameter | 0 h

|

4 h post feeding

|

SEM | p-value

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | Treatment | Hour | Treatment×Hour | ||

| SRL pH | 6.12 | 6.21 | 6.45 | 5.92 | 5.93 | 5.73 | 0.051 | 0.938 | 0.134 | 0.077 |

| TVFA (m mole/dl) | 34.1 | 20.7 | 18.4 | 34.0 | 22.0 | 25.7 | 1.53 | 0.007 | 0.334 | 0.586 |

| Acetic acid (m mole/dl) | 15.8 | 11.5 | 9.70 | 15.9 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 0.69 | 0.025 | 0.724 | 0.322 |

| Propionic acid (m mole/dl) | 10.6 | 5.0 | 3.80 | 10.9 | 7.l0 | 7.6 | 0.68 | 0.039 | 0.183 | 0.580 |

| Butyric acid (m mole/dl) | 5.8 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 0.43 | 0.041 | 0.102 | 0.679 |

| Acetic+butyric/propionic | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.13 | 0.247 | 0.061 | 0.450 |

| Propionic acid/TVFA | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.009 | 0.270 | 0.085 | 0.384 |

| Protozoa population (×104 ml) | ||||||||||

| Holotrichs | 12.4 | 9.96 | 8.8 | 20.8 | 15.1 | 10.54 | 5.452 | 0.027 | 0.546 | 0.932 |

| Spirotrichs | 121.9 | 86.47 | 69.7 | 113.4 | 87.1 | 55.84 | 9.898 | 0.008 | 0.241 | 0.983 |

| Total | 134.4 | 96.44 | 78.5 | 125.5 | 103.8 | 64.27 | 10.537 | 0.027 | 0.546 | 0.932 |

RBO: Rice bran oil. Ca-soap: Calcium soap made of rice bran oil. SEM: Standard error of mean. TVFA: Total volatile fatty acids.

In agreement to our results Hightshoe et al. (1991) also reported no change in rumen pH by supplementing rumen protected fat in beef cattle however rumen pH was lowered at 4 h post feeding which agreed well with the findings of Cheng et al. (1980). Sutton et al. (1983) also reported decreased population of rumen ciliate protozoa by feeding free oils to sheep due to inhibition of the H2 producing fermentation process caused by disruption of the symbiotic relationship between rumen protozoa and methanogenic bacteria and subsequent interspecies H2 transfer (Finlay et al., 1994). Dietary inclusion of fats reduced energy available to bacteria because of limited fat digestion in the rumen, thus, decreased microbial protein synthesis and VFA production (Khorasani et al., 1992). Fat supplementation also depressed ruminal digestion through an inhibitory effect of fatty acids on fiber digestion and decreased VFA production.

Carcass traits and composition

Differences were observed for pre slaughter (p = 0.004) and hot carcass weight (p≤0.05): the weights were lower in rice bran oil and higher in Ca-soap supplemented group as compared to control (Table 6). However, the dressing yield, loin eye area and body fat distribution were similar in these groups.

Table 6.

Carcass characteristics of experimental lambs

| Parameter | Control | RBO (40 g/kg) | Ca-soap (40 g/kg) | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcass traits | ||||

| Pre slaughter weight (kg) | 27.1b | 23.3a | 30.7c | 1.45 |

| Hot carcass weight (kg) | 14.5b | 12.5a | 16.4c | 1.12 |

| Dressing percent on PSW | 53.4 | 53.6 | 53.0 | 0.69 |

| Dressing per cent on ELW | 58.1 | 58.0 | 58.5 | 0.429 |

| Loin eye area (cm2) | 11.22 | 11.93 | 13.14 | 1.12 |

| Shear Force value | 3.22 | 2.35 | 2.74 | 0.19 |

| Subcutaneous fat (g/kg) | 111 | 99 | 101 | 4.33 |

| Inter muscular fat (g/kg) | 106 | 91.7 | 96.7 | 9.42 |

| Total fat (g/kg) | 211 | 183 | 193 | 19.9 |

| Lean (g/kg) | 530a | 571b | 550b | 10.8 |

| Bone (g/kg) | 170.3 | 165.6 | 171.1 | 18.2 |

| Composition of Longissimus dorsi muscle | ||||

| Moisture (g/kg) | 672 | 670 | 686 | 3.63 |

| Crude Protein (g/kg) | 174 | 177 | 186 | 5.45 |

| Total Ash (g/kg) | 13.7 | 13.3 | 19.1 | 1.62 |

| Fat (g/kg) | 140 | 139 | 108 | 7.11 |

RBO = Rice bran oil. Ca-soap = Calcium soap made of rice bran oil. SEM = Standard error of mean.

PSW = Pre slaughter weight. ELW = Empty live weight. Values wearing different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p<0.05).

Pre slaughter and hot carcass weights in different groups differed due to differences in pre slaughter live weights. Manso et al. (2006) recorded no difference in carcass yield and body chemical composition of lambs by supplementing fat in ration. Reason for lack of difference by fat supplementation may be ascribed to slaughter of lambs at an early stage of maturity as fat deposition mainly occurred during later stages of growth (Butterfield, 1988). It is well established that fat accumulation in the body is age dependent and subcutaneous fat is accumulated at the latter stage of growth. Leon et al. (1999) reported higher body fat reserves at 12 and 16 months of age as compared to 8 month old lambs.

CONCLUSIONS

Supplementation of calcium soap of rice bran at 40 g/kg feed improved energy intake by virtue of higher concentrate intake which in turn improved body weight gain and feed conversion ratio with acceptable carcass traits during post weaning. On the contrary, rice bran oil as such reduced concentrate intake, gain in weight and feed conversion ratio hence not found useful for targeting higher gains of lambs in semi arid environment.

REFERENCES

- Alexander G, Prabhakara Rao Z, Rama Prasad J. Effect of supplementing sheep with sunflower acid oil or its calcium soap on nutrient utilization. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2002;15:1288–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Allen MS, Bradford BJ, Oba M. The hepatic oxidation theory of the control of feed intake and its application to ruminants. J Anim Sci. 2009;87:3317–3334. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis of the AOAC International. 17th ed. 1 and 2. Association of Official Analytical Chemists; Gaithersburg, MD, USA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural Research Council . Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux. Farham Royal; UK: 1990. The nutrient requirement of ruminant livestock. Supplement 1. Agricultural Research Council; pp. 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt RS, Tripathi MK, Verma DL, Karim SA. Effect of different feeding regimes on pre weaning growth, rumen fermentation and its influence on post weaning performance of lambs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2009;93:568–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2008.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt RS, Soren NM, Tripathi MK, Karim SA. Effects of different levels of coconut oil supplementation on performance, digestibility, rumen fermentation and carcass traits of Malpura lambs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2011;164:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt RS, Sahoo A, Shinde AK, Karim SA. Effect of supplementing calcium soap of fatty acids on biochemical profile, rumen fermentation, pre- and post-weaning growth and carcass traits of Malpura lambs. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2012 (Accepted) [Google Scholar]

- Bindel DJ, Drouillard JS, Titgemeyer EC, Wessels RH, Loest CA. Effects of ruminally protected choline and dietary fat on performance and blood metabolites of finishing heifers. J Anim Sci. 2000;78:2497–2503. doi: 10.2527/2000.78102497x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield RM. New concepts of sheep growth. University of Sidney; Sidney, NSW, Australia: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KJ, Fay JP, Howarth RE, Costerton JW. Sequence of events in the digestion of fresh legume leaves by rumen bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:613–625. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.3.613-625.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinquart A, Micol D, Brundseaux C, Dufrasne I, Istasse L. Utilisation des matierres grasses chez les bovines avec a I’engraissement. INRA Prod Anim. 1995;8:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DB. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics. 1955;11:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Febel H, Husveth F, Veresegyhazy T, Andrasofszky E, Varheqyi I, Huszar S. Effect of different fat sources on in vitro degradation of nutrients and certain blood parameters in sheep. Acta Vet Hung. 2002;50:217–229. doi: 10.1556/AVet.50.2002.2.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay BJ, Estaben G, Clarke KJ, Williams AG, Embley TM, Hirt RP. Some rumen ciliates have endosymbiotic methanogens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;117:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad SG, Younis HM. The effect of addind ruminally protected fat in fattening diets on nutrient intake, digestibility and growth performance of Awassi lambs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2004;113:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hightshoe RB, Cochran RC, Corah LR, Harmon DL, Vanzant ES. Influence of source and level of ruminal escape lipid in supplements on forage intake, digestibility, digesta flow and fermentation characteristics in beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 1991;69:4974–4982. doi: 10.2527/1991.69124974x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISI . Fresh, chilled and frozen. Bureau of Indian Standard Institution; New Delhi, India: 1963. Indian standard specifications for mutton and goat flesh. IS 2536. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TC, Palmquist DL. Effect of fatty acids or calcium soaps on rumen and total nutrient digestibility of dairy rations. J Dairy Sci. 1984;67:978–986. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81396-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim SA, Bhatt RS. Small ruminant production in India: issues and approaches. In: Sahoo A, Sankhyan SK, Swarnkar CP, Shinde AK, Karim SA, editors. Trends in small ruminant production: perspectives and prospects. SSPH Delhi; India: 2012. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani GR, de Boer G, Robinson PH, Kennelly JJ. Effect of canola fat on ruminal and total tract digestion, plasma hormones and metabolites in lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75:492–501. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)77786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani GR, Kennelly JJ. Effect of added dietary fat on performance, rumen characteristics, and plasma metabolites of mid lactation dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81:2459–2468. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronfield DA, Donoghue S. Digestibility and associative effects of protected tallow. J Dairy Sci. 1980;63:642–645. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)82985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AE, Olmos MC, Cruz E, Garcia R. Accumulation of body fat in Cuban Pelibuey lambs according to age and feeding level. Arch Zootech. 1999;48:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Leng RA. Dynamics of protozoa in the rumen. In: Nolan JV, Leng RA, Demeyer DI, editors. The role of protozoa and fungi in ruminant digestion, proceeding of an international seminar held at the university of New England. Armidale, NSW; Australia: 1989. pp. 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenco ALG, Dias-da-Silva AA, Fonseca AJM, Azevedo JT. Effects of live weight, maturity and genotype of sheep fed a hay based diet on intake, digestion and live weight gain. Livest Prod Sci. 2000;63:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Machmuller A, Ossowski DA, Kreuzer M. Comparative evaluation of the effects of coconut oil, oilseeds and crystalline fat on methane release, digestion and energy balance in lambs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2000;85:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Machmüller A, Kreuzer M. Methane suppression by coconut oil and associated effects on nutrient and energy balance in sheep. Can J Anim Sci. 1999;79:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Manso T, Castro T, Mantecon AR, Jimeno V. Effects of palm oil and calcium soaps of palm oil fatty acids in fattening diets on digestibility, performance and chemical body composition of lambs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2006;127:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Naik PK, Saijpaul S, Neelam Rani. Evaluation of rumen protected fat prepared by fusion method. Anim Nutr Feed Technol. 2007;7:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nestel PJ, Poyser A, Hood RL, Mills SC, Willis MR, Cook LJ, Scott TW. The effect of dietary fat supplements on cholesterol metabolism in ruminants. J Lipid Res. 1978;19:899–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigdi ME, Loerch SC, Fluharty FL, Palmiquist DL. Effect of calcium soaps of long chain fatty acids on feedlot performance, carcass characteristics and ruminal metabolism of steers. J Anim Sci. 1990;68:2555–2565. doi: 10.2527/1990.6882555x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JM, Bories G, Aumaitre A, Barrier-Guillet B, Delaveau A, Gueguen L, Larbier M, Sauvant D. Consequences en elevage et pour le consommateur du remplacement des farines et des graisses animals. INRA Prod Anim. 2002;15:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy RY, Krishna N, Raghava Rao E, Janardgana Reddy T. Influence of dietary protected lipids on intake and digestibility of straw based diets in deccani sheep. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2003;106:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo A, Agarwal Neeta, Kamra DN, Chaudhary LC, Pathak NN. Influence of the level of molasses in de-oiled rice bran based concentrate mixture on rumen fermentation pattern in crossbred calves. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1999;80:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Santra A, Karim SA. Growth performance of faunated and defaunated Malpura weaner lambs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2002;86:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Santra A, Karim SA, Singh VK. Defaunation for improving mutton and wool production in sheep. Central sheep and wool research institute; Rajasthan, India: 2007. Avikanagar-304 501. [Google Scholar]

- Shipe WF, Senyk GF, Fountain KB. Modified copper soap solvent extraction method for measuring free fatty acids in milk. J Dairy Sci. 1980;63:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sklan D, Nagar Lily, Arieli A. Effect of feeding different levels of fatty acids or calcium soaps of fatty acids on digestion and metabolizable energy in sheep. Anim Prod. 1990;50:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS . Statistical package for social sciences. SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA: 2005. Statistical package for social sciences, SPSS 140 for Windows. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton JD, Knight R, McAllan AB, Smith RH. Digestion and synthesis in the rumen of sheep given diets supplemented with free and protected oils. Br J Nutr. 1983;49:419–432. doi: 10.1079/bjn19830051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinder P. Determination of blood glucose using an oxidase-peroxidase system with a non carcinogenic chromogen. J Clin Pathol. 1969;22:158–161. doi: 10.1136/jcp.22.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods of dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber and non starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. Symposium: carbohydrate methodology, metabolism and nutritional implications in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanapat M, Petlum A, Chanthai S. Effects of level of urea and coconut oil on rumen ecology, milk yield and composition in lactating dairy cows fed on urea- treated rice straw. Workshop on”Making better use of local feed resources. 2005 2005 May 23–25; Thailand. http://www.mekarn.org/proctu/wana13.htm.

- Wu Z, Ohajuruka OA, Palmquist DL. Ruminal synthesis, bio-hydrogenation and digestibility of fatty acids by dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3025–3034. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wybenga DR, Pilegg VJ, Dirstine PH, Di Giorgio J. Direct manual determination of serum total cholesterol with a single stable reagent. Clin Chem. 1970;16:980–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf AM, Olafadehan OA, Obun CO, Inuma M, Garba MH, Shagwa SM. Nutritional evaluation of sheabutter fat in fattening of Yankasa sheep. Pakistan J Nutr. 2009;8:1062–1067. [Google Scholar]