Abstract

Hormonal and nutrient signals regulate leptin synthesis and secretion. In rodents, leptin is stored in cytosolic pools of adipocytes. However, not much information is available regarding the regulation of intracellular leptin in ruminants. Recently, we demonstrated that leptin mRNA was expressed in bovine intramuscular preadipocyte cells (BIP cells) and that a cytoplasmic leptin pool may be present in preadipocytes. In the present study, we investigated the expression of cytoplasmic leptin protein in BIP cells during differentiation as well as the effects of various factors added to the differentiation medium on its expression in BIP cells. Leptin mRNA expression was observed only at 6 and 8 days after adipogenic induction, whereas the cytoplasmic leptin concentration was the highest on day 0 and decreased gradually thereafter. Cytoplasmic leptin was detected at 6 and 8 days after adipogenic induction, but not at 4 days after adipogenic induction. The cytoplasmic leptin concentration was reduced in BIP cells at 4 days after treatment with dexamethasone, whereas cytoplasmic leptin was not observed at 8 days after treatment. In contrast, acetate significantly enhanced the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in BIP cells at 8 days after treatment, although acetate alone did not induce adipocyte differentiation in BIP cells. These results suggest that dexamethasone and acetate modulate the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in bovine preadipocytes.

Keywords: Acetate, Bovine, Cytoplasm, Dexamethasone, Leptin, Preadipocyte

INTRODUCTION

Leptin is a 16-kDa protein that is secreted mainly by adipocytes. It is well known that leptin causes physiological effects such as reduction in food intake and increases in metabolic rate via signal transduction between brain and adipose tissues (Friedman and Halaas, 1998). Serum leptin concentration and adipose leptin mRNA level were found to increase in proportion to body mass (Maffei et al., 1995; Considine et al., 1996), thus circulating leptin is a useful marker of adiposity and for the assessment of long-term nutritional conditions. However, leptin gene expression in adipocytes and the circulating leptin concentration are subject to short-term regulation, especially by the nutritional status (Coleman and Hermann, 1999; Saladin et al., 1999). For example, food intake and the injection of insulin into rodents or humans increase leptin mRNA expression in adipose tissues.

Previous studies have shown that leptin is stored in cytosolic pools of adipocytes (Roh et al., 2000; Lee and Fried, 2006). Interestingly, increased leptin release into the culture medium is not always accompanied by coordinated changes in gene expression (Bradley and Cheatham, 1999; Lee et al., 2007). Indeed, previous reports have shown that the incubation of rat adipocytes with insulin increases leptin release without affecting the leptin mRNA level. Therefore, the regulation of intracellular leptin may be important for understanding the roles of leptin in physiological and nutritional signals. Several hormones can modulate leptin secretion in vivo and in vitro. Most previous systematic studies have focused on two principle candidates, glucocorticoids and insulin. Glucocorticoids have been shown to consistently increase in vivo leptin secretion in normal rats and humans as well as in primary in vitro cultures of adipocytes (Larsson and Ahren, 1996; Slieker et al., 1996; Papaspyrou-Rao et al., 1997; Russell et al., 1998; Jahng et al., 2008). Several studies have demonstrated a stimulatory effect of insulin on expression of leptin gene and/or secretion of leptin (MacDougald et al., 1995; Gettys et al., 1996; Rentsch and Chiesi, 1996; Wabitsch et al., 1996).

However, not much information is available regarding the regulation of intracellular leptin in ruminant adipocytes. Japanese Black cattle, which have large deposits of intramuscular fat, are a suitable model for investigating the process of adipose development in muscle. Thus, we established a preadipocyte clonal cell line (BIP), which was derived from the intramuscular adipose tissue of Japanese Black cattle (Aso et al., 1995). BIP cells have the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into mature adipocytes; therefore, they may be useful for studying the mechanisms of adipocyte differentiation or adipogenic hormone expression/secretion in ruminants. Recently, we demonstrated that BIP cells can synthesize leptin during the preadipocyte stage and that a cytoplasmic leptin pool may be present in these preadipocytes (Yonekura et al., 2013). In the present study, we focused on cytosolic leptin protein and investigated its expression in BIP cells during differentiation. We also studied the effects of several factors added to the differentiation medium on the expression of cytoplasmic leptin protein in BIP cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; 5.5 mM glucose) was purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was provided by Microbiological Associates (Walkersville, MD). The rabbit anti-leptin polyclonal antibody was purchased from Chemicon International Inc (Temecula, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG was used as a secondary antibody (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK). Recombinant murine leptin was purchased from Chemicon International Inc. The remaining compounds were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical (Osaka, Japan).

Cell culture and adipocyte differentiation

BIP cells, a bovine intramuscular preadipocyte clonal line (Aso et al., 1995), were plated at a density of 2.0×104 cells/cm2 in 9-cm dishes (Nunc, Rochester, NY) or six-well plates (Nunc) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were grown in this culture medium at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Differentiation into adipocytes was initiated by treating confluent BIP cells with differentiation medium (DMEM containing 50 ng/mL insulin, 250 nM dexamethasone, 5 mM octanoate, 10 mM acetate, and 10% FBS). The medium were changed every other day. The cells in six-well plates were used for triglyceride (TG) measurements, whereas the cells in the 9-cm dishes were used for Western blotting and RT-PCR, as described below.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from BIP cells using the TRIzol reagent (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Poly A+ RNA was isolated from total RNA using an mRNA isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The concentration of the isolated mRNA was determined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm, and the purity of the RNA was determined based on the ratio of the absorbance at 260 nm relative to the absorbance at 280 nm. RT-PCR was performed as described previously (Yonekura et al., 2013). PCR amplification of the cDNA samples was conducted using the following bovine leptin gene primer pair: 5′-GTGCCCATCCGCAAGGTCCA-3′ and 5′-TCAGCACCCGGGACTGAGGT-3′ (450-bp product, GenBank accession no. U50365). The PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and analyzed using the Fluor-S MultiImager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Western blotting

The cells were homogenized in ice-cold buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM EGTA, 2 mM PMSF, and 1% aprotinin (pH 7.5). The homogenates were centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min at 4°C. The total cell extracts were collected and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The cell extracts (60 μg), and recombinant murine leptin (0.3, 0.1, and 0.03 μg) as a standard, were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 15% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated for 2 h in 0.2% Tween 20/PBS (PBS-Tween) containing 5% skim milk powder (blocking buffer), followed by incubation with anti-leptin antibody in blocking buffer at room temperature. After incubating with the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, the immunoreactive bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL-Plus; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were exposed to Kodak XAR5 film for 10 min, and images were analyzed using NIH Image software. Quantification of cytoplasmic leptin concentration was performed as described previously (Yonekura et al., 2003).

TG measurement

Cells cultured in six-well plates were washed with PBS, scraped off into 0.4 mL of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM EDTA, and homogenized. TG in the cell lysate was extracted with the same volume of chloroform-methanol (2:1, v/v) and quantified enzymatically using the Triglyceride G-test kit (Wako Chemical Inc., Osaka, Japan).

Statistical analysis

In all of the experiments, the values were expressed as the mean±SEM, with at least three replicates in each experimental group. To determine the statistical significance, the values were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test. The differences were considered significant at p<0.01.

In order to determine differences in TG concentration at different stimulation day, statistical significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer analysis. The test was considered significant if p< 0.05.

RESULTS

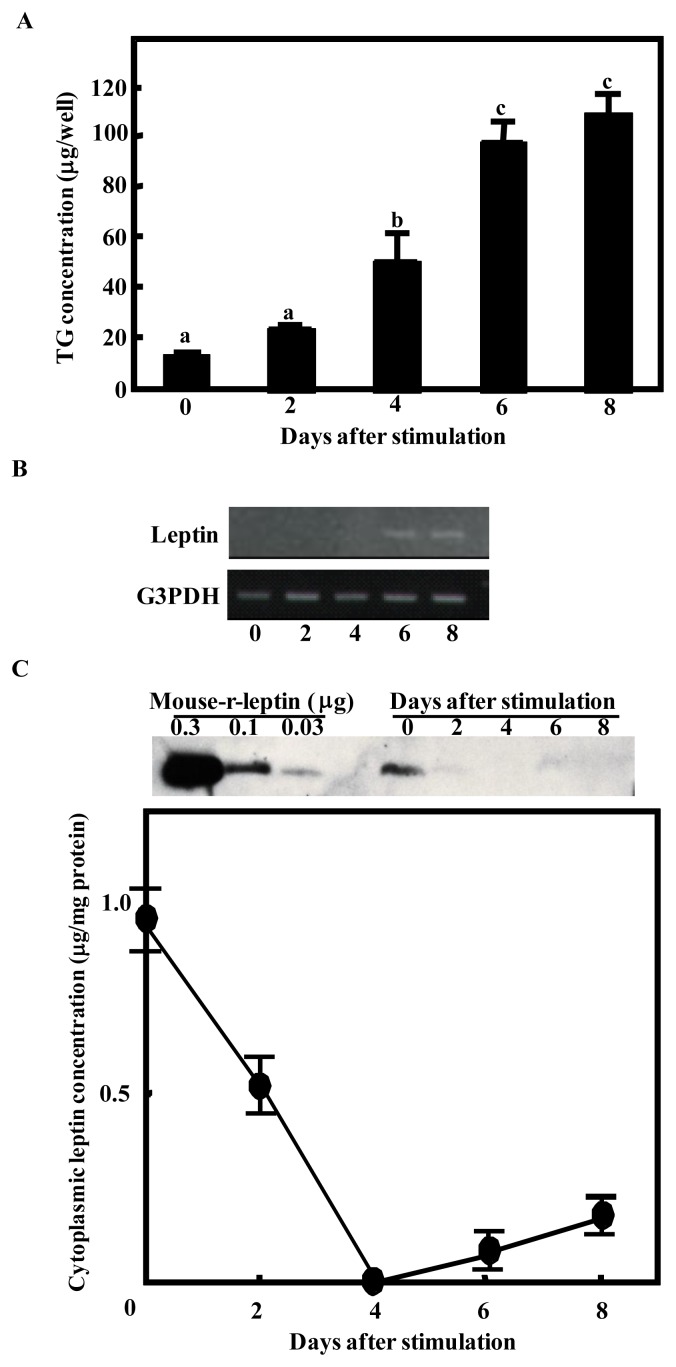

Leptin expression in BIP cells during differentiation

BIP cells never accumulated TG spontaneously in the growth medium. After stimulation with differentiation medium, they exhibited a marked increase in lipogenesis (Figure 1A). The expression of leptin mRNA was studied during the conversion of BIP cells to adipocytes by RT-PCR. Leptin mRNA expression was observed only at 6 and 8 days after induction (Figure 1B). Next, we examined the cytoplasmic leptin concentration at the same time points by western blotting (Figure 1C). The cytoplasmic leptin concentration was the highest at day 0 and decreased gradually thereafter. The cytoplasmic leptin was not detected at 4 days after induction, but not at 6 and 8 days after induction.

Figure 1.

Leptin mRNA expression level and cytoplasmic leptin concentration in bovine intramuscular preadipocyte cells (BIP cells) during differentiation. After reaching confluence, adipocyte differentiation was initiated by the addition of differentiation factors. (A) Triglyceride (TG) accumulation was assessed in BIP cells on the day after induction. Points with a different superscript (a, b, c) are significantly different (p<0.05) (B) RT-PCR of the expression of leptin (upper panel) and G3PDH (lower panel) mRNA in BIP cells on the day indicated after induction. The results are representative of three similar experiments. (C) Cell lysates were collected at the day indicated after induction. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody for leptin. Recombinant murine leptin (Murine r-leptin) protein was included at 1.0, 0.3, and 0.1 μg per well as a positive control. The intensities of the bands were analyzed using NIH Image software and murine leptin was used as a standard to quantify bovine leptin. Y-axis indicates that leptin contents per 1 mg cytoplasmic proteins. The results represent the mean±SEM for three independent determinations. This is representative of three similar experiments.

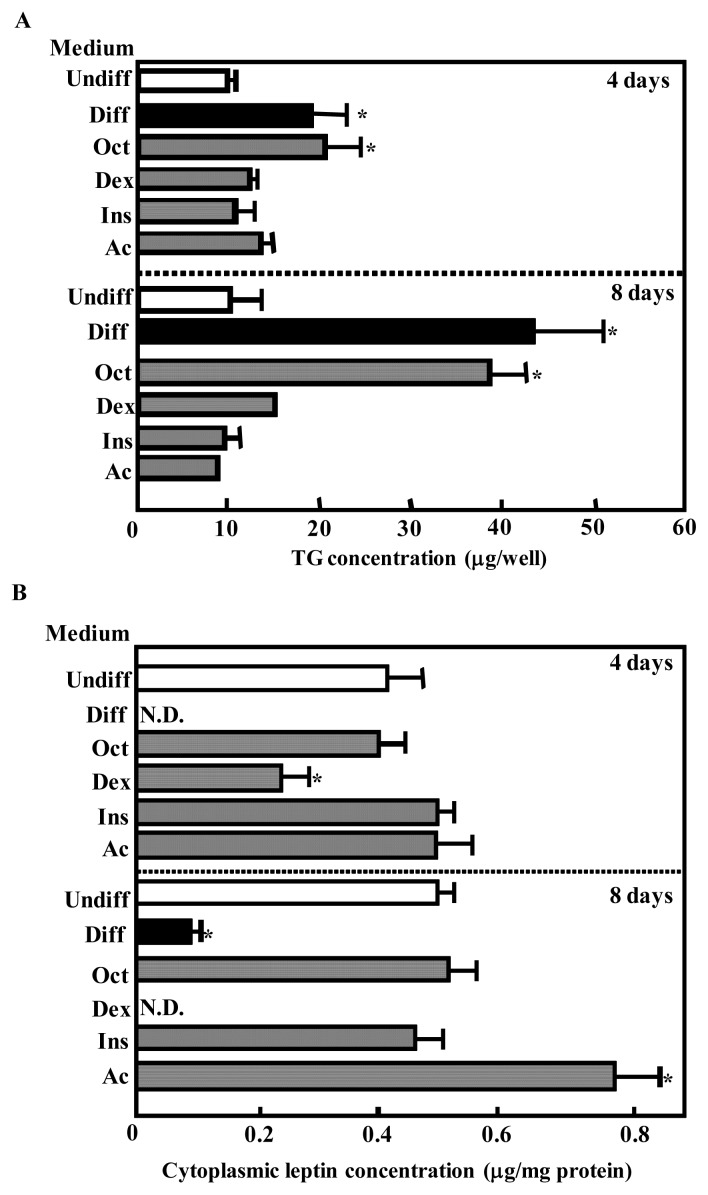

Effects of adipogenic factors on the cytoplasmic leptin concentration

To investigate the specific component in the differentiation medium that affected the cytoplasmic TG or leptin concentration, BIP cells were grown to confluence and exposed to medium supplemented with various agents. In these culture conditions, octanoate produced a marked increase in lipid accumulation within the BIP cells at 4 and 8 days after incubation (Figure 2A). The cytoplasmic leptin concentration was decreased in BIP cells after treatment with dexamethasone at 4 days and cytoplasmic leptin was not detected at 8 days after treatment (Figure 2B). In contrast, acetate significantly enhanced the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in BIP cells at 8 days after treatment (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Effects of adipogenic factors on triglyceride (TG) accumulation (A) and the cytoplasmic leptin concentration (B) in bovine intramuscular preadipocyte cells (BIP cells). After reaching confluence, cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) without (Undiff) or with 5 mM octanoate, 0.25 mM dexamethasone, 50 ng/mL insulin, and 10 mM acetate (Diff) or with 5 mM octanoate (Oct), 250 nM dexamethasone (Dex), 50 ng/mL insulin (Ins), or 10 mM acetate (Ac). At day 4 and 8 after treatment, TG accumulation was assessed and the cell lysates were collected. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody for leptin. Recombinant murine leptin (Murine r-leptin) protein was also included at 1.0, 0.3, and 0.1 μg per well as a positive control. The intensities of the bands were analyzed using NIH Image software and murine leptin was used as a standard to quantify bovine leptin. The results represent the mean±SEM for three independent determinations. * p<0.01 vs Undiff.

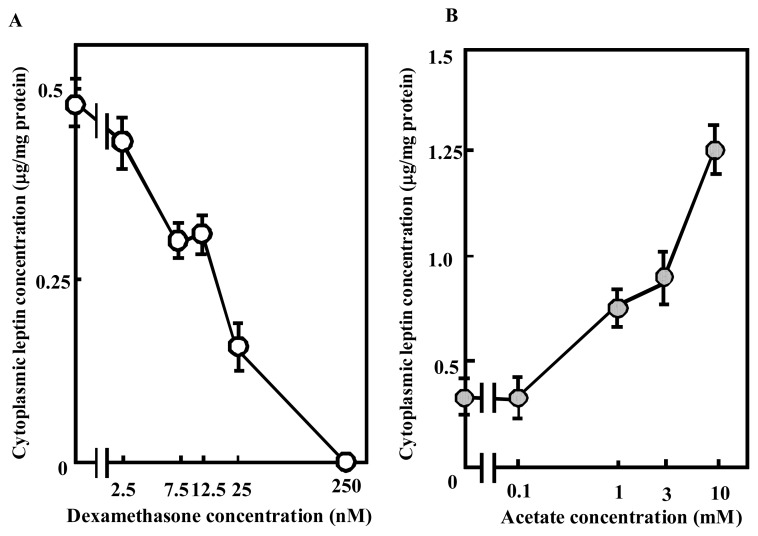

Effects of dexamethasone and acetate on the cytoplasmic leptin concentration

The results showed that dexamethasone and acetate modulated the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in BIP cells. We also demonstrated that these effects were dose dependent. When dexamethasone was added to the medium at 2.5, 7.5, 12.5, 25, or 250 nM, the cytoplasmic leptin concentration decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3A). In addition, when acetate was added to the medium at 1, 3, or 10 mM, the cytoplasmic leptin concentration increased in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent effects of dexamethasone and acetate on the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in bovine intramuscular preadipocyte cells (BIP cells). After reaching confluence, cells were cultured for 8 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with dexamethasone (2.5, 7.5, 12.5, 25, and 250 nM) or acetate (0.1, 1, 3, and 10 mM). The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody for leptin. Recombinant murine leptin (Murine r-leptin) protein was also included at 1.0, 0.3, and 0.1 μg per well as a positive control. The intensities of the bands were analyzed using NIH Image software and murine leptin was used as a standard to quantify bovine leptin. Y-axis indicates that leptin contents per 1 mg cytoplasmic proteins. The results represent the mean±SEM for three independent determinations.

DISCUSSION

Recently, we demonstrated that BIP cells can synthesize leptin during the preadipocyte stage (Yonekura et al., 2013). In the present study, we showed that completely differentiated BIP cells expressed leptin mRNA, as reported previously in rodent adipocytes and primary cultures of bovine adipocytes (Rentsch and Chiesi, 1996; Soliman et al., 2007). Cytoplasmic leptin was observed when leptin mRNA was detected. This suggested that cytoplasmic leptin might be attributable to newly synthesized leptin. We measured the level of secreted leptin in the conditioned medium using ELISA but it was detected only at 6 and 8 days after induction (data not shown). These results indicate that leptin is newly synthesized and secreted rapidly from fully differentiated BIP cells. Leptin mRNA was not expressed at day 0 when the cytoplasmic leptin concentration was the highest, indicating that there may be a cytoplasmic leptin pool in preadipocytes. We also showed that the cytoplasmic leptin concentration decreased gradually after adipogenic stimulation, without affecting the leptin mRNA level. Previous reports have shown that increased leptin release into the culture medium is not always accompanied by coordinated changes in gene expression (Bradley and Cheatham, 1999; Lee et al., 2007). We were not able to detect the secreted leptin in the conditioned medium during this period (data not shown), but the results suggest that adipogenic factors in the differentiation medium promoted the secretion of leptin from an intracellular pool.

We found that dexamethasone decreased the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in BIP cells. Previous studies have shown that dexamethasone increased leptin release from human adipocytes (Slieker et al., 1996; Considine et al., 1997). Therefore, our results suggest that dexamethasone stimulated the release of leptin from a preformed pool in the preadipocyte cytoplasm. However, the molecular mechanism that allows dexamethasone to mediate leptin release from a cytoplasmic pool remains to be elucidated. Rodent studies have suggested that insulin can increase leptin release from adipocytes (Gettys et al., 1996; Bradley and Cheatham, 1999), whereas our results showed that insulin did not affect the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in BIP cells. These different results in bovine preadipocytes and rodents may be attributable to species-specific responses. Ruminant adipocytes exhibit insulin resistance due to their lower insulin signal transduction activity. A reduction in glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) translocation, which is stimulated by insulin, has also been observed in ovine adipocytes (Sasaki, 2002).

Some studies have reported that short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as acetate, which is a major energy source in ruminants, stimulate leptin mRNA expression in both murine and bovine adipocytes via a G protein-coupled receptor for SCFA (Xiong et al., 2004; Soliman et al., 2007). Our results indicate that acetate enhanced the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in BIP cells but that acetate alone did not induce adipocyte differentiation in BIP cells. Overall, these results suggest that acetate can also stimulate leptin production in bovine preadipocytes. We also found that leptin expression was up-regulated by acetate in bovine anterior pituitary cells (Yonekura et al., 2003). Acetate is the principal energy source for the ruminant and represents about 99% of the plasma SCFA concentration in these species. These findings suggest that leptin expression is regulated by nutrient availability.

In conclusion, our data clearly demonstrate that dexamethasone and acetate modulate the cytoplasmic leptin concentration in bovine preadipocytes. These results suggest that leptin release and leptin gene expression in bovine preadipocytes are affected greatly by nutritional factors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported in part by a Hokuto Foundation for Bioscience award to Dr. S. Yonekura.

REFERENCES

- Aso H, Abe H, Nakajima I, Ozutsumi K, Yamaguchi T, Takamori Y, Kodama A, Hoshino FB, Takano S. A preadipocyte clonal line from bovine intramuscular adipose tissue: nonexpression of GLUT-4 protein during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:369–375. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RL, Cheatham B. Regulation of ob gene expression and leptin secretion by insulin and dexamethasone in rat adipocytes. Diabetes. 1999;48:272–278. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RA, Hermann TS. Nutritional regulation of leptin in humans. Diabetologia. 1999;42:639–646. doi: 10.1007/s001250051210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauuciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ, Bauer TL, Caro JF. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:292–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Nyce MR, Kolaczynski JW, Zhang PL, Ohannesian JP, Moore JH, Jr, Fox JW, Caro JF. Dexamethasone stimulates leptin release from human adipocytes: unexpected inhibition by insulin. J Cell Ciochem. 1997;65:254–258. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(199705)65:2<254::aid-jcb10>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettys TW, Harkness PJ, Watson PM. The beta 3-adrenergic receptor inhibits insulin-stimulated leptin secretion from isolated rat adipocytes. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4054–4057. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng JW, Kim NY, Ryu V, Yoo SB, Kim BT, Kang DW, Lee JH. Dexamethasone reduces food intake, weight gain and hypothalamic 5-HT concentration and increases plasma leptin in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;581:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Ahren B. Short-term dexamethasone treatment increases plasma leptin independently in insulin sensitivity in healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4428–4432. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.12.8954054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Fried SK. Multivel regulation of leptin storage, turnover, and secretion by feeding and insulin in rat adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1984–1993. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600065-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Wang Y, Gong DW, Fried SK. Feeding and insulin increase leptin translation: Importance of the leptin mRNA untranslated regions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:72–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougald OA, Hwang CS, Fan H, Lane MD. Regulated expression of the obese gene product (leptin) in white adipose tissue and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 1995;92:9034–9037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E, Pratley RE, Lee GH, Zhang Y, Fei H, Kim S, Lallone R, Ranganathan S, Kern PA, Friedman JM. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat Med. 1995;11:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaspyrou-Rao S, Schneider SH, Petersen RN, Fried SK. Dexamethasone increases leptin expression in human in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1635–1637. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.5.3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch J, Chiesi M. Regulation of ob gene mRNA levels in cultured adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 1996;379:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh C, Thoidis G, Farmer SR, Kandror KV. Identification and characterization of leptin-containing intracellular compartment in rat adipose cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E893–E899. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.4.E893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CD, Petersen RN, Rao SP, Ricci MR, Prasad A, Zhang Y, Brolin RE, Fried SK. Leptin expression in adipose tissue from obese humans: depot-specific regulation by insulin and dexamethasone. Am J Physiolo Endocrinol Metab. 1998;275:E507–E515. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.3.E507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin R, De Vos P, Guerre-Millo M, Leturque A, Girard J, Staels B, Auwerx J. Transient increase in obese gene expression after food intake or insulin administration. Nature. 1995;377:527–528. doi: 10.1038/377527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S. Mechanism of insulin action on glucose metabolism in ruminants. Anim Sci J. 2002;73:423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Slieker LJ, Sloop KW, Surface PL, Kriauciunas A, LaQuier F, Manetta J, Bue-Valleskey J, Stephens TW. Regulation of expression of ob mRNA and protein by glucocorticoids and cAMP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5301–5304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman M, Kimura K, Ahmed M, Yamaji D, Matsushita Y, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Makondo K, Saito M. Inverse regulation of leptin mRNA expression by short- and long-chain fatty acids in cultured bovine adipocytes. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2007;33:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wabitsch M, Jensen PB, Blum WF, Christoffersen CT, Englaro P, Heinze E, Rascher W, Teller W, Tornqvist H, Hauner H. Insulin and cortisol promote leptin production in cultured human fat cells. Diabetes. 1996;45:1435–1438. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.10.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Miyamoto N, Shibata K, Valasek MA, Motoike T, Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate leptin production in adipocytes through the G protein-coupled receptor GPR41. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2004;101:1045–1050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637002100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura S, Tokutake Y, Hirota S, Rose MT, Katoh K, Aso H. Proliferating bovine intramuscular preadipocyte cells synthesize leptin. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2013;45:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura S, Senoo T, Kobayashi Y, Yonezawa T, Katoh K, Obara Y. Effects of acetate and butyrate on the expression of leptin and short-form leptin receptor in bovine and rat anterior pituitary cells. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2003;133:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(03)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]