Abstract

High human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1)-expression has shown a survival benefit in pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine in several studies. The aim of this systematic review was to summarize the results and try to assess the predictive value of hENT1 for determining gemcitabine outcome in pancreatic cancer. Relevant articles were obtained from PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases. Studies evaluating hENT1-expression in pancreatic tumor cells from patients treated with gemcitabine were selected. Outcome measures were overall survival, disease-free survival (DFS), toxicity and response rate. The database searches identified 10 studies that met the eligibility criteria, and a total of 855 patients were included. Nine of 10 studies showed a statistically significant longer overall survival in univariate analyses in patients with high hENT1-expression compared to those with low expression. In the 7 studies that reported DFS as an outcome measure, 6 had statistically longer DFS in the high hENT1 groups. Both toxicity and response rate were reported in only 2 articles and it was therefore hard to draw any major conclusions. This review provides evidence that hENT1 is a predictive marker for pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine. Some limitations of the review have to be taken into consideration, the majority of the included studies had a retrospective design, and there was no standardized scoring protocol for hENT1-expression.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Gemcitabine, hENT1, Predictive, Survival

Core tip: Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 is a predictive marker for pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine.

INTRODUCTION

Gemcitabine is the standard chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer[1-3], but its efficacy is limited; only 15% of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer[4] and up to 30% in general[5] can be expected to respond to treatment. Gemcitabine is hydrophilic and therefore passive diffusion through hydrophobic cellular membranes is slow[1]. Permeation through the membranes requires specialized membrane transporters[1,3], and human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) is the most important for gemcitabine[6,7]. Because gemcitabine is a prodrug, it has to be phosphorylated after intracellular uptake[1] in order to have a cytotoxic effect[6]. This rate-limiting step is carried out by the enzyme deoxycytidine kinase (dCK)[8].

Recent research has revealed that differences in the expression of genes, including hENT1[9,10] and enzymes involved with gemcitabine metabolism, such as dCK, may be predictors of the efficacy of gemcitabine treatment for pancreatic cancer[11]. Several studies have indicated that high expression of hENT1 is associated with longer overall survival (OS) and longer disease-free survival (DFS)[9,10,12].

The aim of this review was to evaluate and summarize the potential predictive value of hENT1 expression in pancreatic tumor cells in patients treated with gemcitabine.

STUDY SELECTION

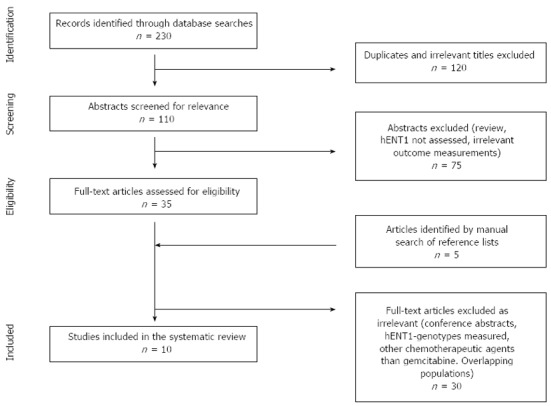

To identify all relevant English-language articles published from 1966 to March 2013, a computerized search of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases was performed. The following search terms were used: (hENT1 OR nucleoside transporter), (gemcitabine OR gemzar), (pancreatic OR pancreas), (cancer OR adenocarcinoma OR neoplasm). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)[13] was used as a guideline for the processing and reporting of the results. The initial search yielded 230 publications (54 in PubMed, 1 in the Cochrane database, 175 in Embase). To find studies that might have been missing in the database search, a manual search was made by reading through reference lists of relevant articles and systematic reviews. The results of the search and the selection of studies are shown in Figure 1. The quality of the included articles was assessed using the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK)[14].

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing article selection process.

ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

For inclusion in this systematic review, the following criteria had to be met: retrospective or prospective studies of patients with pancreatic cancer, all stages, treated with gemcitabine with or without additional radiation; the expression of hENT1 had to be reported and related to patient outcome; and the articles had to be available in full text and published in English. Exclusion criteria were conference abstracts, overlapping patient cohorts and studies in which the relevant outcomes of interest were not addressed.

DATA EXTRACTION

A data extraction form was completed before the extraction process began. The form was reviewed by a second author (RA) to ensure that all relevant information was being extracted. The data extraction was done by a single reviewer (SN) and the following data were extracted from each study: publication details [author(s), date of publication, location, study center], study design, population details (age, sex, pT-stage, pN-stage), patient number, type of intervention (dose, schedule, duration), method to determine hENT1-expression, hENT1-scoring, primary and secondary outcome measurements, and results correlated with hENT1-expression.

OUTCOMES OF INTEREST AND DEFINITION

The primary outcome measures were OS and DFS correlated with hENT1 expression. Secondary outcome measures were toxicity according to the Common Toxicity Criteria (http://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/), and response rate according to RECIST[15] criteria.

LITERATURE SEARCH

The search identified 230 references in the 3 databases. Of these, 120 were excluded after identification of duplicates and exclusion based on irrelevant titles. Abstracts from 110 articles were screened and 75 were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion were: nonclinical trials (such as review articles), hENT1-expression was not being assessed, and irrelevant outcome measurements. The remaining 35 studies were retrieved for further assessment. Of these, 25 references were excluded for the following reasons: they were conference abstracts and not full-text articles; hENT1-subgroups were measured[16,17]; hENT1 was evaluated as a prognostic factor rather than a predictive factor of gemcitabine treatment[18]; there were overlapping patient populations[19]; and too small sample size/case reports[20]. An additional 5 article abstracts were screened for eligibility after identification in a manual search of reference lists of relevant articles. All of these were excluded based on irrelevance. In total, 10 studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria and were included in this systemic review.

CHARACTERISTICS OF SELECTED STUDIES

The included articles were published between 2004 and 2012. They originated from Belgium (2 studies)[1,3], Canada (one study)[9], United States (one study)[12] and Japan (5 studies)[2,8,21-23]. The 5 studies from Japan originated from 5 different universities, Kyushu, Osaka, Yokohama, Mie and Hiroshima. One author had published 2 articles[1,3], for one of these the patient population was recruited from 2 centers, while for the other the patient population was recruited from 5 centers. The potential bias of overlapping patient populations was therefore small, but must nevertheless be taken into consideration in the analysis of the results.

Nine of 10 studies were retrospective[1-3,8-10,21-23] and one was a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled study[12]. The 10 studies involved a total of 855 patients and the sample size varied from 21 to 234 (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the identified studies

| Ref. | Year of publication | Country | Inclusion period | No. of patients | Study design | Follow-up median (95%CI), mo |

| Spratlin et al[9] | 2004 | Canada | 1998–2002 | 21 | RS | NR |

| Giovannetti et al[10] | 2006 | Italy | 2001–2004 | 1021 | RS | 11.2 (0.4–32.1) |

| Farrell et al[12] | 2009 | United States | 1998–2002 | 91 | Post hoc2 | NR |

| Maréchal et al[3] | 2009 | Belgium | 2000–2003 | 45 | RS | 21.9 (3.3–107.4) |

| Fujita et al[8] | 2010 | Japan | 1992–2007 | 70 | RS | 15.7 (0.5–114) |

| Maréchal et al[1] | 2012 | Belgium | 1996–2009 | 234 | RS | 55.7 (46.4–61.2) |

| Kawada et al[2] | 2012 | Japan | 2002–2007 | 63 | RS | 31 |

| Morinaga et al[21] | 2012 | Japan | 2006–2008 | 27 | RS | NR |

| Murata et al[22] | 2012 | Japan | 2005–2010 | 93 | RS | 15 (3.5–57.2) |

| Nakagawa et al[23] | 2012 | Japan | 2002–2011 | 109 | RS | 39.7 (2–122) |

| Total: 855 |

n = 81 with complete hENT1;

Post hoc analysis of randomized controlled trial. NR: Not reported; RS: Retrospective.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the identified studies

| Ref. | Age median, yr (range) | Sex m/tot n (%) | hENT1 method | Chemotherapy | Radiation dose Gy/(Gy/frac) | Outcome measurement | Quality REMARK |

| Spratlin et al[9] | 58 (51-64)1 | 11 (52) | IHC | Pall Gem | No | OS | 10 |

| Giovannetti et al[10] | 65 (22-83) | 53 (50) | RT-PCR | Pall Gem Adj Gem | 45 | OS, DFS, TTP, RR | 12 |

| Farrell et al[12] | 53/63/652 | 45 (49) | IHC | Adj Gem | 50.4 | OS, DFS, Tox | 17 |

| Maréchal et al[3] | 56 (34-83) | 23 (51) | IHC | Adj Gem | 40-50.4 | OS, DFS, Tox | 13 |

| Fujita et al[8] | 65 (36-86) | 42 (60) | RT-PCR | Adj Gem or Resection only | No | OS, DFS | 12 |

| Maréchal et al[1] | NR | 129 (53) | IHC | Adj Gem | 50.4 | OS | 15 |

| Kawada et al[2] | - (41-81) | 33 (52) | IHC | Neo Gem Adj 5-FU | 50/2 | DSS | 9 |

| Morinaga et al[21] | 64 (45-74) | 17 (63) | IHC | Adj Gem | No | OS, DFS | 12 |

| Murata et al[22] | 68 (44-87) | 38 (69) | IHC | Neo Gem Adj Gem | 45/2 | OS, DFS, RR | 13 |

| Nakagawa et al[23] | 67 (41-83) | 52 (48) | IHC | Adj Gem + S1 | No | OS, DFS | 13 |

95%CI;

Medians in the different hENT1 expression groups. IHC: Immunohistochemistry; RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; Adj: Adjuvant; Neo: Neoadjuvant; Radio: Radiotherapy; Gem: Gemcitabine; Pall: Palliative; OS: Overall survival; DFS: Disease-free survival; Tox: Toxicity; TTP: Time to progression; DSS: Disease-specific survival; RR: Response rate.

Four studies[1,8,10,12] used parallel groups, while the remainder were single-arm studies. The treatment protocols, which differed between the studies, included adjuvant gemcitabine monotherapy, palliative gemcitabine treatment, neoadjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy, adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy + radiation, neoadjuvant gemcitabine + radiation (and adjuvant 5-fluorouracil), resection only and neoadjuvant gemcitabine-based chemoradiation + adjuvant gemcitabine (Table 2). All protocols were based on gemcitabine treatment and resection of the tumor.

hENT1 EXPRESSION

To quantify hENT1-expression, 8 studies used immunohistochemistry (IHC) and 2 used reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Grading of the expression differed between the studies, as is described in more detail in Table 3. The majority of the studies dichotomized the expression in high/positive vs low/negative hENT1 expression. There were no standardized scoring procedures available.

Table 3.

hENT1 expression levels, cut-offs and grouping

| Ref. | Method | Grading | Reference cells | Groups (n) |

| Spratlin et al[9] | IHC | 0-2 based on relative intensities of staining. | Langerhans cells, lymphocytes. | Dichotomized: |

| 0 = absence of staining | Low = 0 (12) | |||

| 1 = intermediate staining | High = 1 and 2 (9) | |||

| 2 = most intense staining | ||||

| Giovannetti et al[10] | RT-PCR | Gene-expression ratio with GAPDH, expressed as tertiles | Gene expression tertiles: | |

| GAPDH/target gene ratio | Low < 1.06 (27) | |||

| Intermediate 1.06-1.38 (28) | ||||

| High ≥ 1.38 (26) | ||||

| Dichotomized: | ||||

| By medians | ||||

| Low < 1.23 (44) | ||||

| High ≥ 1.23 (37) | ||||

| Farrell et al[12] | IHC | Based on relative intensities. | Lymphocytes | Dichotomized: |

| High = strong reactivity in > 50% of neoplastic cells. | No (18)1 | |||

| No = no staining in > 50% | vs | |||

| Low = all cases between High and No. | Low/high (73)1 | |||

| Maréchal et al[3] | IHC | 0-3 based on staining intensities | Langerhans cells | Dichotomized: |

| 0 = no staining | Lymphocytes | Low < 80 (26) | ||

| 1 = weakly positive | (final score) | |||

| 2 = moderately positive | ||||

| 3 = strongly positive | High = ≥ 80 (19) | |||

| Final score calculated: multiplying intensity score and the percentage of the specimen. Weighted score 0-300 | ||||

| Fujita et al[8] | RT-PCR | Level of mRNA calculated from standard curve constructed with total RNA from Capan-1, a human pancreatic cancer cell line | mRNA split into high/low groups using recursive descent partitioning. Cut-off 0.5 | |

| Low (26)1 | ||||

| High (14) | ||||

| Maréchal et al[1] | IHC | 0-2 based on staining intensities | Lymphocytes | Dichotomized: |

| Quantified as Farrell | Low/moderate (136)1 | |||

| High (86)1 | ||||

| Kawada et al[2] | IHC | 0-2 based on staining intensities. | Langerhans cells | Negative = 0-1 (41) |

| 1 = same intensity as control. | Positive = 2 (22) | |||

| Morinaga et al[21] | IHC | Staining intensity and percentage of positive tumor cells scored and given a hENT1-score by calculating the two | Low = hENT1 score 0-3 (11) | |

| Staining 0-3 where | High = hENT1 score 4-6 (16) | |||

| 0 = no | ||||

| 1= weakly pos | ||||

| 2 = moderately pos | ||||

| 3 = strongly pos | ||||

| Percentage: | ||||

| 0 = no positive | ||||

| 1 ≤ 50% positive cells | ||||

| 2 = 50%-80% positive cells | ||||

| 3 = ≥ 80% | ||||

| Murata et al[22] | IHC | Staining intensity + extent of positive staining | Langerhans cells | Dichotomized: |

| Intensity: | Negative = low and intermediate (16) | |||

| 0 = no staining | ||||

| 1 = weakly positive | Positive = high (39) | |||

| 2 = moderately positive | ||||

| 3 = strongly positive | ||||

| Extent staining: | ||||

| High = score 3 > 50% cells | ||||

| Low = score 0 or 1 > 50% | ||||

| Intermediate = all others | ||||

| Nakagawa et al[23] | IHC | Staining intensities: | Langerhans cells | Low = grade 0 or 1 in > 50% (31) |

| 0 = not stained | High = grade 2 or 3 in > 50% of cells (78) | |||

| 1 = faintly stained | ||||

| 2 = weakly stained | ||||

| 3 = as strongly as islet cells |

In gem arm. GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

OVERALL SURVIVAL

Nine of the 10 included studies had OS as an outcome measurement of interest (Table 4). Kawada et al[2] was the sole study that only reported disease-specific survival (DSS) as the primary outcome. The definition of DSS is the length of time from either the date of diagnosis or start of treatment for a specific disease (e.g., pancreatic cancer), and that the patients with the disease still are alive. The difference from OS is that OS measures death from any cause, not just death from a particular disease. Survival times for the individual studies were calculated based on: diagnosis, in one study[10]; the start of gemcitabine treatment in 2 studies[9,22]; resection, in 5 studies[1,3,8,21,23]; and randomization in one study[12].

Table 4.

Results

| Ref. | Median survival all patients (95%CI) |

OS |

DFS |

Main conclusions | ||

| Univariate analysis median (95%CI) or HR (95%CI) P-value | Multivariate analysis HR (95%CI) | Univariate analysis median (95%CI) or HR (95%CI) P-value | Multivariate analysis HR (95%CI) | |||

| Spratlin et al[9] | 11.01 (6.8-17.5) | (mo): | NR | Pat with detectable hENT1 had sig longer OS compared with pat with low hENT1 | ||

| High = 13 (4.2-20.4) | ||||||

| 5.01 (2.8-12.2) | Low = 4 (1.5-6.9) | |||||

| P = 0.01 | ||||||

| Giovannetti et al[10] | 13.3 (10.9-15.7) | (mo): | Low = 5.34 (2.28-12.50) | Palliative (mo): | hENT1 expression was significantly correlated with outcome - pat with high hENT1 had longer OS | |

| Low = 8.48 (7.01-9.95) | Low = 5.85 (2.75-8.95) | |||||

| Inter = 15.74 (13.84-17.63) | Inter = 1.07 (0.46-2.49) | Inter = 10.09 (9.63-10.54) | ||||

| High = 25.69 (17.64-33.74) | High = 1 | High = 12.68 (2.89-22.47) | ||||

| P ≤ 0.001 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.02 | ||||

| 2 groups: | ||||||

| 2 groups: | HR = 4.21 | Adjuvant (mo): | ||||

| Low = 12.42 (8.18-16.66) | P ≤ 0.001 | Low = 9.26 (3.86-14.67) | ||||

| High = 22.34 (16.34-28.34) | Inter = 12.91 (9.31-16.51) | |||||

| P ≤ 0.001 | High = 20.43 (13.27-27.60) | |||||

| P ≤ 0.01 | ||||||

| Farrell et al[12] | NR | (HR): | Low/high = 0.40 (0.22-0.75) | (HR): | Low/high = 0.39 (0.21-0.73) | hENT1 expression was ass with longer OS, DFS in pat receiving gem. hENT1 is a relevant predictive marker for gem outcome |

| Low/High = 0.51 (0.29-0.91) | Low/High = 0.57 (0.32-1.001) | |||||

| No = 1 | No = 1 | No = 1 | No = 1 | |||

| P = 0.02 | P = 0.03 | P = 0.05 | P = 0.003 | |||

| Maréchal et al[3] | 21.9 (3.3-107.4) | (HR): | High = 1 | (HR): | High = 1 | Pat with high hENT1 had sig longer OS and DFS compared to low hENT1 |

| High = 1 | Low = 3.42 (1.44-8.81) | High = 1 | Low = 3.17 (1.43-6.73) | |||

| Low = 3.88 (1.78-8.92) | P = 0.0005 | Low = 3.55 (1.65-7.63) | P = 0.0004 | |||

| P = 0.0007 | P = 0.02 | |||||

| Fujita et al[8] | NR | (mo): | (RR): | (mo): | NR | Low hENT1 ass with shorter OS in gem-group |

| High = 45 | Low = 2.980 (0.964-10.86) | High = 25 | ||||

| Low = 16.5 | Low = 8 | |||||

| P = 0.011 | P = 0.2 (not sig) | P = 0.11 (not sig) | ||||

| Maréchal et al[1] | 32.0 (26.4-34.3) | (HR): | n = 2222 | NR | NR | High hENT1 predicts longer OS in pat treated with adj gem. Absence of gem - hENT1 lacks prognostic value |

| High = 0.43 (0.29-0.63) | High = 0.34 (0.22-0.53) | |||||

| (GEM-group) | Low/Mod = 1 | Low/Mod = 1 | ||||

| P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | |||||

| Kawada et al[2] | NR | Positive vs negative | Positive/negative | NR | NR | DSS tended to be better in the hENT1-neg group but not statistically sig |

| P = 0.352 | P = 0.503 | |||||

| Morinaga et al[21] | NR | (mo): | Low = 1 | (mo): | Low = 1 | High hENT1 sig ass with longer OS in pat receiving adj gem after resection |

| Low = 11.8 (6.9-16.6) | High = 0.327 (0.128-0.835) | Low = 7.3 (3.6-11.1) | High = 0.558 (0.214-1.452) | |||

| High = 22.2 (11.5-32.9) | High = 9.3 (4.2-14.5) | |||||

| P = 0.024 | P = 0.019 | P = 0.022 | P = 0.232 | |||

| (HR): | (HR): | |||||

| Low = 1 | Low = 1 | |||||

| High = 0.366 (0.148-0.906) | High = 0.362 (0.146-0.898) | |||||

| P = 0.030 | P = 0.028 | |||||

| Murata et al[22] | 24.3 | (HR): | Positive = 1 | (HR): | Positive = 1 | Sig longer OS, RFS in pat with pos hENT1 |

| Positive = 1 | Negative = 3.15 (1.35-7.37) | Positive = 1 | Negative = 1.76 (0.85-3.66) | |||

| Negative = 3.04 (1.45-6.37) | Negative = 2.34 (1.22-4-47) | |||||

| P = 0.0037 | P = 0.008 | P = 0.011 | P = 0.129 | |||

| Nakagawa et al[23] | OS: 34.9 | (5y-SR %): | High = 1 | (5y-SR %): | High = 1 | hEN1 expression is predictive of the efficacy of adj gem-based chemotherapy after resection |

| DFS: 17.8 | High = 38 | Low = 3.16 (1.65-6.06) | High = 30 | Low = 2.70 (1.52-4.83) | ||

| Low = 13 | Low = 17 | |||||

| P = 0.001 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.004 | P = 0.001 | |||

From diagnosis/from treatment;

n = 222 in multivariate analysis. Ass: Associated; pat: Patient; sig: Significant; adj: pos: Positive; op: Operation; HR: Hazard ratio; SR: Survival rate; RFS: Recurrence-free survival.

In univariate analyses, all 9 studies that had OS as an outcome measurement of interest showed a survival benefit with gemcitabine treatment and high/positive expression of hENT1 compared with patients with low/negative hENT1 expression. Multivariate analyses were conducted in 8 of the 9 studies. Seven of these identified high/positive hENT1 as an indicator of longer OS in patients with pancreatic cancer who received gemcitabine treatment. One study[8] indicated a trend towards better OS in the multivariate analysis, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.2).

DISEASE-FREE SURVIVAL

In 7 studies, DFS was reported as an outcome measurement (Table 4). DFS was calculated from the same starting points as reported above for OS. Six of these studies showed a statistically significant longer DFS in univariate analyses. One study[8] was not statistically significant with regard to hENT1. Multivariate analyses were conducted in 5 studies but of these only 3[3,12,23] reported statistically significant results with longer DFS in regard to hENT1 in patients with pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine. Morinaga et al[21] and Murata et al[22] also performed multivariate analyses, but the results did not prove to be statistically significant with reported P-values ranging from 0.129 to 0.232.

TOXICITY

Only 2 studies addressed the issue of toxicity[3,12], but the numbers published were inadequate for further analysis. Farrell et al[12] tried to find a relationship between hENT1-levels and the incidence of grade III or higher toxicities; however no relationship was found using a logistic regression model. The analysis data were not shown in the article. Maréchal et al[3] reported that grade III/IV hematological toxicities were noted in 10/45 patients and grade III/IV nonhematological in 3/45 patients. They did not relate this finding to hENT1 expression and no further data or data analysis was shown in the article with regard to toxicity.

RESPONSE RATE

Of the 10 included studies only 2[10,22] reported the outcome measurement response rate (RR). Giovannetti et al[10] evaluated RR in 34/36 patients in a group of patients receiving palliative treatment with gemcitabine. Two of the patients were not evaluable because of early death and refusal. The results showed that 5 patients had a partial response, 13 had stable disease and 16 had progressive disease. No further evaluation or data analysis was made with respect to RR. Murata et al[22] evaluated RR in respect to hENT1 expression; radiographic RR was judged according to RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors). Radiographic RR was not significantly correlated with hENT1 expression (P = 0.665).

DISCUSSION

Based on the data collected from the selected studies, there is evidence that hENT1 expression is a predictive marker for pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine. Patients with high expression of hENT1 had significantly longer OS in all included studies that evaluated this outcome measurement. These results are in accordance with other studies of gemcitabine outcome correlated with hENT1 expression in other types of tumors, including biliary tract cancer[24], cholangiocarcinoma[25], bladder cancer[26] and non-small cell lung cancer[27].

Since there is no standardized protocol for the grading of hENT1 expression, the methods used differed between the included studies (Table 3). The majority used immunohistochemistry to evaluate hENT1 expression in the tumor cells. This is the main method for assessing biomarkers in histopathology. Most studies in this review using this method of evaluation had 2 independent assessors (blinded to each other and to patient outcomes) to make the grading for higher quality and better precision. The different ways of grading protein expression is an issue that needs to be considered when assessing the results of independent studies as well as the results of this review. There is a need for standardized protocols to achieve better homogeneity across studies when it comes to grading the protein expression of hENT1 in pancreatic tumor cells.

Gemcitabine is the standard treatment for patients with pancreatic cancer. This is based on several studies where gemcitabine has shown a survival benefit compared with other treatment regimes[1,28-30]. In this review, the treatment differed amongst the included studies, but they all used gemcitabine as the basis for chemotherapy. Most studies were performed in resectable patients, but the predictive value of hENT1 was also confirmed in unresectable patients[9,10]. Kawada et al[2] used neoadjuvant chemoradiation and their results showed, in contrast with all the others, a trend towards better DSS in patients with low expression of hENT1, although the results were not statistically significant. They did use a slightly different outcome measurement that may have influenced the results. Even though the result was not statistically significant it raises some questions that are important in the discussion about the different treatment regimens across the studies. In the case of neoadjuvant treatment or neoadjuvant chemoradiation, tumor cells with high expression of hENT1 may be destroyed before the tumor samples are collected and will therefore give misleading information. This creates interesting issues as to when and how the tumor cells should be analyzed. Fine needle aspiration is discussed as an option for retrieving tumor cells for evaluation of hENT1. This method can be used before resection and may therefore be an effective tool to identify which patients may benefit from neoadjuvant treatment with gemcitabine. Future studies are needed in this area.

One study[12] was a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial, which is of course rated higher methodologically than are retrospective cohort studies. The common opinion is that a systematic review exhibits the greatest strength if the majority of the included studies are randomized controlled trials or at least prospective trials. However, no such trials have been made within this area, but the need for a review was still considered to be necessary. The retrospective design of the included studies implies that we need to consider reporting and selection bias when analyzing the results.

REMARK[14], which is a relatively new assessment tool, was used for quality evaluation in this review. The maximum score in REMARK is 20, and the average score in the included articles was 12.6 within the range of 9-17. Since this is a relatively new tool, there is not much information as to what quality is considered high, and what is low. In this review, the included articles were of relatively similar quality (Table 2) according to REMARK.

The results of this review are important to the consideration of future treatment options for patients with pancreatic cancer. According to this review, hENT1 has been proven to be a predictive marker for gemcitabine outcome, thus there are a few considerations to be made. First, if we can alter the expression of hENT1 in the tumor cells to create a higher expression, more patients would benefit from gemcitabine treatment and survive longer. Pretreatment with thymidylate synthase inhibitors has proven to increase the expression of hENT1 in tumor cells in vitro[6]. This might be a way to alter the expression in vivo as well, but further studies are needed. The second option is to find another way for gemcitabine to enter the tumor cells and exert its toxic effect. Research in this area is currently under way, and progress should enable more personalized treatment options for pancreatic cancer patients.

Another aspect for the future is the cost of overtreatment with gemcitabine in patients who do not benefit from it. According to one study conducted on a Swedish pancreatic cancer cohort, EUR 8.6 million would be saved each year in Sweden if hENT1 testing were used to select patients for gemcitabine therapy[31].

CONCLUSION

This review provides evidence that hENT1 is a predictive marker for pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine. However, standardized procedures for evaluating and grading hENT1 expression need to be established. Additionally, more research and preferably prospective trials or randomized controlled trials in this area are needed to confirm the results of this review.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Macedo FI, Rossi RE, Yun S, Zhang Q S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Maréchal R, Bachet JB, Mackey JR, Dalban C, Demetter P, Graham K, Couvelard A, Svrcek M, Bardier-Dupas A, Hammel P, et al. Levels of gemcitabine transport and metabolism proteins predict survival times of patients treated with gemcitabine for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:664–74.e1-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawada N, Uehara H, Katayama K, Nakamura S, Takahashi H, Ohigashi H, Ishikawa O, Nagata S, Tomita Y. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 level does not predict prognosis in pancreatic cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation including gemcitabine. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:717–722. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0514-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maréchal R, Mackey JR, Lai R, Demetter P, Peeters M, Polus M, Cass CE, Young J, Salmon I, Devière J, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 and human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 predict survival after adjuvant gemcitabine therapy in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2913–2919. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto K, Ueno H, Ikeda M, Kojima Y, Hagihara A, Kondo S, Morizane C, Okusaka T. Do recurrent and metastatic pancreatic cancer patients have the same outcomes with gemcitabine treatment? Oncology. 2009;77:217–223. doi: 10.1159/000236022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andriulli A, Festa V, Botteri E, Valvano MR, Koch M, Bassi C, Maisonneuve P, Sebastiano PD. Neoadjuvant/preoperative gemcitabine for patients with localized pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1644–1662. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson R, Aho U, Nilsson BI, Peters GJ, Pastor-Anglada M, Rasch W, Sandvold ML. Gemcitabine chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer: molecular mechanisms and potential solutions. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:782–786. doi: 10.1080/00365520902745039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Manteiga J, Molina-Arcas M, Casado FJ, Mazo A, Pastor-Anglada M. Nucleoside transporter profiles in human pancreatic cancer cells: role of hCNT1 in 2’,2’-difluorodeoxycytidine- induced cytotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5000–5008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita H, Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K, Itaba S, Ito T, Nakata K, Yu J, Kayashima T, Souzaki R, Tajiri T, et al. Gene expression levels as predictive markers of outcome in pancreatic cancer after gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy. Neoplasia. 2010;12:807–817. doi: 10.1593/neo.10458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spratlin J, Sangha R, Glubrecht D, Dabbagh L, Young JD, Dumontet C, Cass C, Lai R, Mackey JR. The absence of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 is associated with reduced survival in patients with gemcitabine-treated pancreas adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6956–6961. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannetti E, Del Tacca M, Mey V, Funel N, Nannizzi S, Ricci S, Orlandini C, Boggi U, Campani D, Del Chiaro M, et al. Transcription analysis of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter-1 predicts survival in pancreas cancer patients treated with gemcitabine. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3928–3935. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashida R, Nakata B, Shigekawa M, Mizuno N, Sawaki A, Hirakawa K, Arakawa T, Yamao K. Gemcitabine sensitivity-related mRNA expression in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of unresectable pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:83. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrell JJ, Elsaleh H, Garcia M, Lai R, Ammar A, Regine WF, Abrams R, Benson AB, Macdonald J, Cass CE, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 levels predict response to gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:187–195. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka M, Javle M, Dong X, Eng C, Abbruzzese JL, Li D. Gemcitabine metabolic and transporter gene polymorphisms are associated with drug toxicity and efficacy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:5325–5335. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okazaki T, Javle M, Tanaka M, Abbruzzese JL, Li D. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of gemcitabine metabolic genes and pancreatic cancer survival and drug toxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:320–329. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim R, Tan A, Lai KK, Jiang J, Wang Y, Rybicki LA, Liu X. Prognostic roles of human equilibrative transporter 1 (hENT-1) and ribonucleoside reductase subunit M1 (RRM1) in resected pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:3126–3134. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo N, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakashima A, Sueda T. Combined analysis of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase and human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression predicts survival of pancreatic carcinoma patients treated with adjuvant gemcitabine plus S-1 chemotherapy after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19 Suppl 3:S646–S655. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalski CW, Erkan M, Sauliunaite D, Giese T, Stratmann R, Sartori C, Giese NA, Friess H, Kleeff J. Ex vivo chemosensitivity testing and gene expression profiling predict response towards adjuvant gemcitabine treatment in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:760–767. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morinaga S, Nakamura Y, Watanabe T, Mikayama H, Tamagawa H, Yamamoto N, Shiozawa M, Akaike M, Ohkawa S, Kameda Y, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter-1 (hENT1) predicts survival in resected pancreatic cancer patients treated with adjuvant gemcitabine monotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19 Suppl 3:S558–S564. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murata Y, Hamada T, Kishiwada M, Ohsawa I, Mizuno S, Usui M, Sakurai H, Tabata M, Ii N, Inoue H, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression is a strong independent prognostic factor in UICC T3-T4 pancreatic cancer patients treated with preoperative gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:413–425. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa N, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Kondo N, Sueda T. Combined analysis of intratumoral human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) and ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M1 (RRM1) expression is a powerful predictor of survival in patients with pancreatic carcinoma treated with adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy after operative resection. Surgery. 2013;153:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santini D, Schiavon G, Vincenzi B, Cass CE, Vasile E, Manazza AD, Catalano V, Baldi GG, Lai R, Rizzo S, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) levels predict response to gemcitabine in patients with biliary tract cancer (BTC) Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:123–129. doi: 10.2174/156800911793743600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi H, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Kondo N, Sueda T. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression predicts survival of advanced cholangiocarcinoma patients treated with gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection. Ann Surg. 2012;256:288–296. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182536a42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumura N, Nakamura Y, Kohjimoto Y, Inagaki T, Nanpo Y, Yasuoka H, Ohashi Y, Hara I. The prognostic significance of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression in patients with metastatic bladder cancer treated with gemcitabine-cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy. BJU Int. 2011;108:E110–E116. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oguri T, Achiwa H, Muramatsu H, Ozasa H, Sato S, Shimizu S, Yamazaki H, Eimoto T, Ueda R. The absence of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression predicts nonresponse to gemcitabine-containing chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2007;256:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, Benson AB, Macdonald JS, Kudrimoti MR, Fromm ML, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ansari D, Tingstedt B, Andersson R. Pancreatic cancer - cost for overtreatment with gemcitabine. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1146–1151. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.744140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]