Abstract

Flowering time is an important agronomic trait in almond since it is decisive to avoid the late frosts that affect production in early flowering cultivars. Evaluation of this complex trait is a long process because of the prolonged juvenile period of trees and the influence of environmental conditions affecting gene expression year by year. Consequently, flowering time has to be studied for several years to have statistical significant results. This trait is the result of the interaction between chilling and heat requirements. Flowering time is a polygenic trait with high heritability, although a major gene Late blooming (Lb) was described in “Tardy Nonpareil.” Molecular studies at DNA level confirmed this polygenic nature identifying several genome regions (Quantitative Trait Loci, QTL) involved. Studies about regulation of gene expression are scarcer although several transcription factors have been described as responsible for flowering time. From the metabolomic point of view, the integrated analysis of the mechanisms of accumulation of cyanogenic glucosides and flowering regulation through transcription factors open new possibilities in the analysis of this complex trait in almond and in other Prunus species (apricot, cherry, peach, plum). New opportunities are arising from the integration of recent advancements including phenotypic, genetic, genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomics studies from the beginning of dormancy until flowering.

Keywords: Prunus dulcis, breeding, almond, flowering time, dormancy, genome, transcription factors, molecular markers

Introduction

From a commercial point of view, flowering time is one of the most important agronomic traits in almond (Prunus dulcis (Miller) D. A. Webb) as it determines the vulnerability of production to late frosts, as well as the use of cultivars for cross-pollination in order to achieve successful pollination when the flowering time of two varieties must coincide (Dicenta et al., 2005).

Breeding new, late flowering almond cultivars is a very long and costly task since, due to the long juvenile period, their first flowering usually occurs in the third year after plantation in the field, or even later. In addition, the influence of climatic factors on this trait obligates the breeder to record the data for several years (Dicenta et al., 1993, 2005). In this sense, it would be very useful to have tools for early selection of the latest flowering seedlings in the nursery (after germination of seeds), which would be planted in the experimental orchards for further selection (Dicenta et al., 2005). Flowering will only happen when dormancy is broken. Endodormancy has been described as the inability of a tree to start floral or vegetative budbreak, even with moderate temperatures. Endodormancy occurs prior to ecodormancy, which happens in late winter and spring and is imposed by temperatures unfavorable to growth (Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2012).

On the other hand, almond and other Prunus species (apricot, cherry, peach, plum, etc.) accumulate a mono cyanogenic glucoside (CNGLc) called prunasin in different vegetative and reproductive parts of the plant, and in the seeds a di-CNGLc called amygdalin (McCarty et al., 1952; Frehner et al., 1990; Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2008). When specific enzymes called β-glucosidases degrade CNGLcs, glucose, benzaldehyde and cyanide are released (Morant et al., 2008). Upon degradation of hydrogen cyanamide—a nitrogen-based chemical compound sprayed in the flower buds—nitroxil and cyanide are released. This brings forward the flowering time in apple, apricot, peach, persimmon, sweet cherry flower buds, etc., when compared to untreated plants (Dozier et al., 1990; George et al., 1992; Faust et al., 1997).

In this work, recent advancements to study flowering time in almond have been included at the phenotypic (observed trait), genetic (inheritance and transmission), genomic (DNA analysis), transcriptomic (gene expression analysis) and metabolomic (metabolites involved, as cyanide content) level.

Phenotypic studies

In general, the accuracy of phenotypic evaluation is critical for further reliable genetic and molecular studies. To diminish the significant influence of the environment, flowering time can be dissected as the sum of two traits: chilling and heat requirements. These can be determined in monitored conditions by measuring the temperatures in the field and simultaneously controlling temperatures and humidity in the growth chamber (Egea et al., 2003; Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2012). Chill requirements have a much stronger effect on flowering time compared to heat requirements (Egea et al., 2003) with a high positive correlation between chilling requirements and flowering time (Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2012).

These results were also verified in other Prunus species such as apricot (P. armeniaca L.) (Ruiz et al., 2007) and sweet cherry (P. avium L.) (Alburquerque et al., 2008). However, Alonso et al. (2005) described a higher influence of heat requirements than chilling requirements on the flowering time in cold areas, using a mathematical model recording temperatures and flowering time, but not evaluating the endodormancy breaking in flower buds.

Genetic studies

Inheritance studies of the genetic control of flowering time on almond showed that flowering time is a polygenic trait (Kester et al., 1977; Dicenta et al., 1993; Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2007a). However, a major dominant gene controlling this trait was described specifically in some descendants of the almond cultivar “Tardy Nonpareil,” considered a late flowering mutant of “Nonpareil” (Kester, 1965; Socias i Company et al., 1999; Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2007a). These authors, studying some descendants of “Tardy Nonpareil,” observed a bimodal distribution for this trait, which was explained by the presence of a late blooming major gene (late blooming, Lb), quantitatively modified by minor genes.

Flowering time of almond has a high heritability (Kester et al., 1977; Dicenta et al., 1993), so crossing late-flowering parents will produce late-flowering seedlings (Dicenta et al., 2005). The best breeding strategy to obtain late-blooming almond descendants is therefore to cross parents as late-blooming as possible, and when the offspring shows a bimodal distribution, the latest-blooming genotypes should be selected, probably carrying the Lb allele, which could be transmitted to its descendants (Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2012).

On the other hand, studies on the genetic basis and inheritance of chilling and heat requirements to break endodormany and ecodormancy in almond are scarcer. Sánchez-Pérez et al. (2012) described a polygenic nature of these traits in accordance with the observed flowering time of seedlings. In addition, these authors observed, in a 2-year study, that the bimodal distribution of chilling requirements in the studied progeny could be explained by the presence of the Lb gene hypothetically linked to these chilling requirements. In other Prunus, quantitative inheritance of chilling requirements for breaking endodormancy was also observed in flower buds in peach (Fan et al., 2010) and vegetative buds in apricot (Olukolu et al., 2009). In this species, a higher influence of chilling requirements on flowering time was also described, although a single recessive gene called EVERGROWING (EVG) gene (Rodríguez et al., 1994) was described as a chilling and heat requirement related gene (Bielenberg et al., 2004, 2008). Interestingly, the deletion of four out of six of the Dormancy Associated MADS-box (DAM1-DAM6) genes in the evg mutant caused the transcriptional inhibition of the other two structurally intact genes of the family (Bielenberg et al., 2008), in which no flowering occurred.

More is known about the genetic bases of flowering time in the long day plant Arabidopsis thaliana than Prunus species. More than 60 genes were identified as regulating flowering time in Arabidopsis (Ehrenreich et al., 2009), and due to SNPs present in genes including CONSTANS (CO), FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3, PHYTOCHROME D, GIBBERELLIN, etc. or coding region deletions as in FRIGIDA gene, there are different phenotypes for flowering time in Arabidopsis. In fact, dominant alleles of FRI generate late flowering phenotypes while FRI mutants are early flowering (Johanson et al., 2000; Jung and Müller, 2009). Early flowering is also possible if APETALA1 (AP1) is constitutively expressed (Chi et al., 2011). When PsAP1, AP1 from cherry (Prunus avium L.), was over-expressed in Arabidopsis, it produced an early flowering phenotype, shortening the juvenile period (Wang et al., 2013). AP1 belongs to the MADS-box gene family. MdMADS5, an AP1-like gene of apple (Malus × domestica), also caused early flowering in transgenic Arabidopsis (Kotoda et al., 2002), as did MdMADS2 in transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). AP1 is activated by LEAFY (LFY), which is also involved in flowering time in Arabidopsis. Moreover, TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1) and FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) are two key regulators of flowering time. These genes belong to the PEBP family but they have antagonistic functions. TFL1 interacts with b-ZIP transcription factor FD and represses the transcription of FD-dependent genes as AP1 and AGAMOUS (AG), while FT interacting with FD activates AP1 and AG (Wang and Pijut, 2013). TFL1 homologous genes such as PsTFL1 (P. serotina Ehrh., TFL1 homolog) delay flowering when expressed in Arabidopsis. Homologous genes from Arabidopsis found in Prunus species are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Identified genes involved in the regulation of flowering time in Prunus species.

| Specie | Gene | Gene ID | Annotation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. armeniaca | PHYE | Q6SCK5 | Phytochrome E | GeneBank data |

| P. armeniaca | RGA | RGA | Transcription factor | Soriano et al., 2005 |

| P. armeniaca | SOC1 | L7Y228 | Transcription factor | Trainin et al., 2013 |

| P. armeniaca | TFL1 | ADL62862 | Phosphatidylethanolamine binding | Liang et al., 2010 |

| P. avium | APETALA1 | APETALA1 | MADS-box gene family | Wang et al., 2013 |

| P. avium | GA1 | GA1 | Gibberellin biosynthesis | Blake et al., 2000 |

| P. avium | TFL1 | AB636121.1 | Phosphatidylethanolamine binding | Mimida et al., 2012 |

| P. domestica | FT1 | FT1 | Transcription coactivator | Tränkner et al., 2010 |

| P. dulcis | GA20 | BU574794 | Gibberellin 20-oxidase | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. dulcis | LFY | PrdLFY | AFL2 | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. dulcis | MADS1 | PrdMADS1 | MdMADS10 | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. dulcis | PHYA | Q94EK7 | Phytochrome A | GeneBank data |

| P. dulcis | TFL | BU574411 | Flowering locus T-like protein | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. mume | AGL 24 | AB437345.1 | dormancy-associated MADS-box | Yamane et al., 2008 |

| P. mume | FT | AM943979 | Flowering locus T protein | GeneBank data |

| P. serotina | AGAMOUS | EU938540 | Formation of stamens and carpels | Liu et al., 2010 |

| P. persica | AGL 2 | BU048398 | MdMADS 8 | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | AP1 | BU039475 | MdMADS 2 | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | AP2 | BU046298 | AHAP2 | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | ATM YB33 | XM_007218900 | myb domain protein 33 | Zhu et al., 2012 |

| P. persica | CDF1 | XM_007215192 | cycling DOF factor 2 | GeneBank data |

| P. persica | CO | BU042239 | Constans like protein | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | DAM 5 | AB932551 | MADS-box 5 | Yamane et al., 2011 |

| P. persica | DAM 6 | DQ863252 | MADS-box 6 | Bielenberg et al., 2008 |

| P. persica | FAR 1 | BU047045 | Far-red-impaired responsive protein | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | FPF 1 | XM_007225892 | Flowering promoting factor | Romeu et al., 2014 |

| P. persica | FRL 1 | DY640223.1 | FRI-related gene | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | FT | G3GAW0 | Flowering locus T protein | GeneBank data |

| P. persica | FT | BU044758 | Flowering locus T protein | Silva et al., 2005 |

| P. persica | LEAFY | EF175869 | Activator of AP1 | An et al., 2012 |

| P. persica | PHYA | Q945F7 | Phytochrome A | GeneBank data |

| P. persica | PHYB | Q945T4 | Phytochrome B | GeneBank data |

| P. persica | TFL1 | ADL62867 | Phosphatidylethanolamine binding | Liang et al., 2010 |

On the other hand, the adaptation of the short day model plant rice (Oryza sativa L.) to different climate conditions depends on variation in flowering time, also called “heading date (hd).” A number of genes and QTLs have been identified in rice, including Hd1/Se1, Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 (Rice Flowering Locus T1) among others (Ogiso-Tanaka et al., 2013). Functional defects in RFT1 are the main reasons for late flowering rice in an indica cultivar. Hd3, RFT1, and FT are florigen genes. FT protein is the long-sought florigen that activates the transcription of FD, forming the florigen activation complex (FAC). FAC will bind to the promoter regions of floral meristem identity genes such as e.g., AP1, so flowering will occur (Taoka et al., 2013). Therefore, flowering time is affected by florigen in Arabidopsis and rice.

Genomic studies

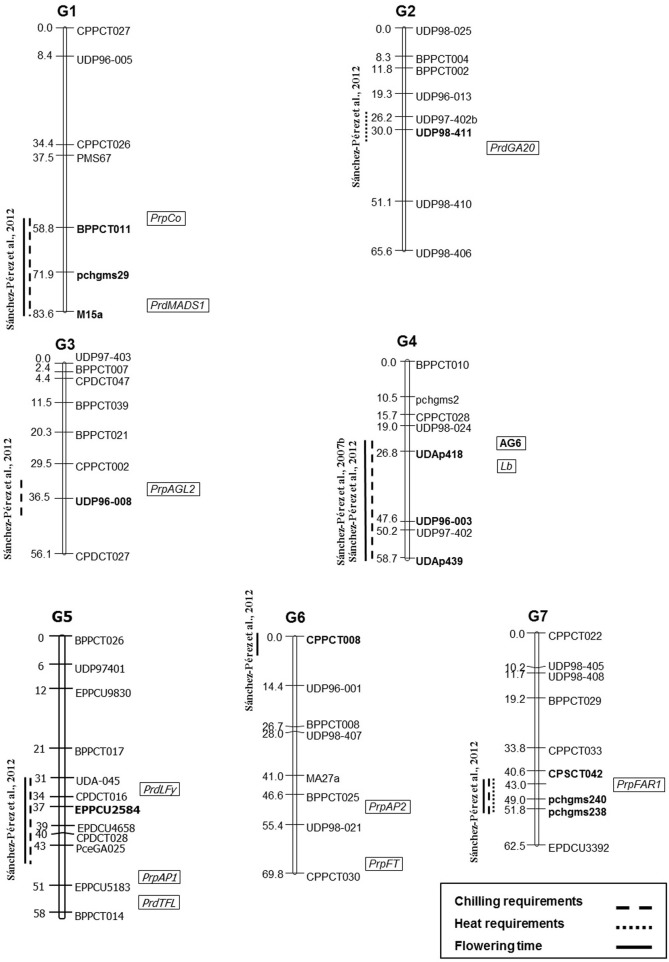

The first genomic studies performed used RAPDs (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) and bulk segregant analysis in a F1 progeny from “Tardy Nonpareil,” corroborating the presence of the previously mentioned major gene Lb controlling late flowering time. Moreover, three RAPDs were found to be associated with Lb in linkage group 4 (G4) of the “Felisia” × “Bertina” (“Felisia” is a descendant from “Titan,” that is a seedling of “Tardy Nonpareil”) genetic map (Ballester et al., 2001). In addition, Silva et al. (2005) described several Quantitative Trait Loci (QTLs) linked to flowering time in an interspecific F1 almond × peach progeny using a Candidate Gene approach (CG) in G1, G2, G3, G5, G6, and G7. More recently, different works using SSR (Simple Sequence Repeat) markers in a F1 population between a seedling of “Tardy Nonpareil” (“R1000”) × “Desmayo Largueta” (R×D), also confirmed the location of Lb in G4 and identified other QTLs to flowering time in G1, G6, and G7 (Sánchez-Pérez et al., 2007b; Martínez-Gómez et al., 2012) (Figure 1). In the first study (2007), carried out in this R×D population, the SSR UDP-96003 was located very close to the Lb gene in G4 of the map. When QTL analysis was performed, this major QTL (Lb) in G4 was able to explain between 56.5 and 86.3% of the variance in “R1000,” which is supposed to carry the Lb gene, and 54.5–67.7% of the variance in the mapped R×D population.

Figure 1.

Location of QTLs linked to flowering time and chilling and heat requirements in the almond map from the population R1000 × Desmayo Largueta performed by Sánchez-Pérez et al. (2007b, 2012). The closest SSR marker linked to the QTL is marked with bold lettering on this map. The approximately location of the RAPD marker (AG6) (Ballester et al., 2001) and candidate genes (in italics) (Silva et al., 2005) linked to flowering time in other almond populations, are indicated inside the boxes. The integration of this information from different genetic maps has been performed using the centimorgan (cM) distances indicated by the different authors in each linkage group and each map.

In other Prunus species, QTLs associated with flowering time were also described in peach, apricot and cherry, confirming the polygenic nature. In peach, Fan et al. (2010) described different QTLs linked to flowering time in G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, and G8. Campoy et al. (2011) and Salazar et al. (2013) described a QTL linked to flowering time in G1, G5, and G7 in apricot. Finally, Wang et al. (2000); Dirlewanger et al. (2012), and Castede et al. (2014) also identified a QTL linked to flowering time in G1, G2, and G4 of sour and sweet cherry.

Silva et al. (2005) and Sánchez-Pérez et al. (2012) described several QTLs linked to chilling (G1, G3, G4, G5, G6, and G7) and heat (G2 and G7) requirements in almond (Figure 1), confirming again its polygenic nature. Fan et al. (2010) also described several QTLs linked to chilling and heat requirements in G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, and G8 in peach. QTLs linked to chilling requirements of vegetative buds were described in apricot by Olukolu et al. (2009) in G1, G2, G3, G5, and G8. In sweet cherry (P. avium L.), Dirlewanger et al. (2012) and Castede et al. (2014) also found one QTL in G4 in sweet cherry.

Moreover, functionally characterized homologs from Arabidopsis were used as a CG approach with 10 genes from almond or peach (PrdLFY, PrdMADS1, PrpAP1, PrpFT, PrpAGL2, PrpFAR1, PrdTFL, PrdGA20, PrpAP2, and PrpCO) (Silva et al., 2005). These 10 genes were mapped in the Prunus reference map (Texas x Earlygold) and can be found in G1, G2, G3 G5, G6, and G7 (Figure 1, Table 1). However, none of them co-localized with Lb gene in G4. One reason for this is that there are more than 60 genes involved in flowering time in Arabidopsis, so other CGs should be analyzed. The other reason could be that the flowering time trait is due to different mechanisms in perennial plants than in annual plants.

The other recent CG analysis study was performed in an area of 3.7 Mbp in G4 (around the Lb gene) and showed 429 genes in the peach Lovell genome (Castede et al., 2014). Based on predicted function of proteins, they selected nine CGs. One of these, ppa002685m, is an embryonic flower 2 gene involved in the vernalization response and a negative regulator of the flower development through histone methylation. It would be interesting to see the analysis of this gene in varieties with different flowering times in almond.

Recently, Zhebentyayeva et al. (2014) developed a comprehensive program to identify genetic pathways and potential epigenetic mechanisms involved in control of chilling requirement and flowering time in peach. These authors described the TFL1, which regulates the vegetative to reproductive transition, and the PcG (polycomb group) genes, which are involved in the epigenetic regulation of flowering in Arabidopsis. It is worth noting that these authors failed to identify a direct FLC gene ortholog and its regulator FRI, suggesting that control of flowering time in Prunus species has a complex genetic architecture.

The recent release of the complete peach genome sequence (Verde et al., 2013) together with four almond genome sequences (Koepke et al., 2013) and the sweet cherry genome publicly available since 2013 (Carrasco et al., 2013), offer new possibilities for integrating genetic and genomic approaches to find new CGs for flowering time in perennial plants (Martínez-Gómez et al., 2012).

Transcriptomic studies

Almond transcriptomic studies have not been performed to date. The only transcriptomic study performed in other Prunus species has been using flower buds of Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc.) at different dormant stages (Habu et al., 2012). In this species, varying flowering time is caused by irregular bud endodormancy release (Zhuang et al., 2013). The transcriptome analysis of flower buds showed 25 endodormant-specific up-regulated unigenes. DAM6 was one of them although, in most of the unigenes, no hit was found. As we have previously mentioned, many of the MADS family genes, such as DAM6, are involved in different steps of flower development including flowering time (Riechmann and Meyerowitz, 1997). At this moment, more than 50 MADs-Type Transcription Factors (TFs) have been identified in the peach genome, so further studies should be done to identify more gene products involved in flowering.

In Arabidopsis, flowering time is dependent on intricate genetic networks to perceive and integrate both endogenous and environmental signals (Khan et al., 2014). In the aging pathway, it has been found that the role of five microRNAs (miRNAs) families called miR156, miR172, miR159/319, miR390, and miR399 is important in flowering time (Spanudakis and Jackson, 2014). Recently, miRNAs differently expressed in chilled peach vegetative buds have been identified co-localizing with known QTLs for chilling requirement and flowering time traits (Barakat et al., 2012; Ríos et al., 2014). A cascade of miRNAs such as miR156, miR172 and their respective targets SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE, and AP2 like genes are involved in modulating flowering induction in Arabidopsis through FT and other flowering related genes (Khan et al., 2014; Spanudakis and Jackson, 2014). Transcriptomic studies in poplar and leafy spurge have shown a differential expression of SPL genes and miR172 during dormancy induction, suggesting that this miRNA pathway may also play a regulating role in dormancy processes that affect flowering time (Ríos et al., 2014).

Application of new high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies (Flintoft, 2008; Martínez-Gómez et al., 2011) could greatly clarify the TFs involved in the regulation of flowering time, allowing the determination of transcripts from a particular region of the genome.

Metabolomic studies

The common by-product upon degradation of hydrogen cyanamide and cyanogenic glucosides is cyanide, which is not only involved in bringing forward flowering time but also in breaking seed dormancy by inducing formation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). ROS activates a cascade in which ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 1 is implicated, producing germination-associated proteins (Oracz et al., 2007). CBF proteins belong to the CBF/DRE binding sub-family of the APETALA2-ETHYLENE responsive factor (Nakano et al., 2006). The action mechanism of nitrogen-based chemical treatments could involve the regulation of the effect of these TFs.

Further, in stone-fruit species (e.g., Prunus species), the presence of common regulatory mechanisms between the chilling requirements for seed and bud dormancy release have been suggested (Leida et al., 2012). Moreover, secondary metabolites as cyanogens were suggested to be involved in the germination of cocklebur seeds (Xanthium pennsylvaniicum Wallr.) in response to various nitrogenous compounds (Esashi et al., 1996). Other cyanogens such as the CNGlc prunasin have been described in flower parts in eucalyptus (Eucalyptus cladocalyx F. Muell.), seeing that young flower buds were the most cyanogenic, when reproductive organs were analyzed at various stages of development (Gleadow and Woodrow, 2000).

The integrated analysis of these well-known mechanisms reveals accumulation of cyanogenic glucosides and regulation of flowering time through TFs, which open new possibilities in the analysis of this complex trait in almond and the rest of Prunus.

New perspectives

Almond is not only the earliest fruit tree to break dormancy but also shows the widest range of flowering time among all fruit and nut species (Socias i Company and Felipe, 1992), making it a suitable candidate for studying this important trait within perennial plants. There are many genes that are conserved during the evolution of flowering plants. However, there are other mechanisms i.e., miRNAs regulation or metabolite signaling, which could be also included in new studies to deepen the analysis of gene regulation of the flowering time in almond. The final objective continues to be the development of efficient molecular markers for selection in breeding programs. This would enable breeders to select the late flowering individuals in the nursery which would allow them to avoid yield losses due to frosts, which currently occurs in early flowering genotypes.

Author contributions

Raquel Sánchez-Pérez and Pedro Martínez-Gómez participated in the coordination of the study. Federico Dicenta and Jorge Del Cueto collected and revised the genetic information. Pedro Martínez-Gómez and Raquel Sánchez-Pérez collected and revised genomic and transcriptomic information. Raquel Sánchez-Pérez and Jorge Del Cueto collected metabolomics information.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the following projects: “Almond breeding” and “Prospection, characterization and conservation of endangered autochthonous almond varieties” by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competiveness and “The molecular mechanisms to break flower bud dormancy in fruit trees” by the VILLUM FOUNDATION's Young Investigator Program (Denmark).

References

- Alburquerque N., García-Montiel F., Carrillo A., Burgos L. (2008). Chilling and heat requirements of sweet cherry cultivars and the relationship between altitude and the probability of satisfying the chill requirements. Environ. Exp. Bot. 64, 162–170 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. M., Ansón J. M., Espiau M. T., Socias i Company R. (2005). Determination of endodormancy break in almond flower buds by a correlation model using the average temperature of different day intervals and its application to the estimation of chill and heat requirements and blooming date. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 130, 308–318 [Google Scholar]

- An L. J., Lei H., Shen X., Li T. H. (2012). Identification and characterization of PpLFL, a homolog of FLORICAULA/LEAFY in peach (Prunus persica). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 30, 1488–1495 10.1007/s11105-012-0459-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballester J., Socias i Company R., Arús P., de Vicente M. C. (2001). Genetic mapping of a major gene delaying blooming time in almond. Plant Breed. 120, 268–270 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2001.00604.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat A., Sriram A., Park J., Zhebentyayeva T., Main D., Abbott A. (2012). Genome wide identification of chilling responsive microRNAs in Prunus persica. BMC Genomics 13:481 10.1186/1471-2164-13-481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg D. G., Wang Y., Fan S., Reighard G. L., Scorza R., Abbott A. G. (2004). A deletion affecting several gene candidates is present in the evergrowing peach mutant. J. Hered. 95, 436–444 10.1093/jhered/esh057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg D. G., Wang Y., Li Z. G., Zhebentyayeva T., Fan S. H., Reighard G. L., et al. (2008). Sequencing and annotation of the evergrowing locus in peach reveals a cluster of six MADS-box transcription factors as candidate geens for regulation of terminal bud formation. Tree Genet. Genomes 4, 495–507 10.1007/s11295-007-0126-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake P. S., Browning G., Benjamin L. J., Manderb L. N. (2000). Gibberellins in seedlings and flowering trees of Prunus avium L. Phytochemistry 53, 519–528 10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00597-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campoy J. A., Ruiz D., Egea J., Rees J., Celton J. M., Martínez-Gómez P. (2011). Inheritance of flowering time in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) and analysis of linked quantitative trait loci (QTLs) using simple sequence repeat markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 29, 404–410 10.1007/s11105-010-0242-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco B., Meisel L., Gebauer M., Garcia-Gonzales R., Silva H. (2013). Breeding in peach, cherry and plum: from a tissue culture, genetic, transcriptomic and genomic perspective. Biol. Res. 46, 219–230 10.4067/S0716-97602013000300001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castede S., Campoy J. A., Quero García J., Le Dantec L., Lafargue M., Barreneche T., et al. (2014). Genetic determinism of phenological traits highly affected by climate change in Prunus avium: flowering date dissected into chilling and heat requirements. New Phytol. 202, 703–715 10.1111/nph.12658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y., Huang F., Liu H., Yang S., Yu D. (2011). An APETALA1−like gene of soybean regulates flowering time and specifies floral organs. J. Plant Physiol. 168, 2251–2259 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicenta F., García J. E., Carbonell E. A. (1993). Heritability of flowering, productivity and maturity in almond. J. Hort. Sci. 68, 113–120 [Google Scholar]

- Dicenta F., García-Gusano M., Ortega E., Martínez-Gómez P. (2005). The possibilities of early selection of late flowering almonds as a function of seed germination or leafing time of seedlings. Plant Breed. 124, 305–309 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2005.01090.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dirlewanger E., Quero-García J., Le Dantec L., Lambert P., Ruiz D., Dondini L., et al. (2012). Comparison of the genetic determinism of two key phonological traits, flowering and maturity dates, in three Prunus species: peach, apricot and sweet cherry. Heredity 109, 280–292 10.1038/hdy.2012.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier W. A., Powell A. A., Caylor A. W., McDaniel N. R., Garden E. L., McGuire J. A. (1990). Hydrogen cyanamide induces budbreak of peaches and nectarines following inadequate chilling. Hortscience 25, 1573–1575 [Google Scholar]

- Egea J., Ortega E., Martínez-Gómez P., Dicenta F. (2003). Chilling and heat requirements of almond cultivars for flowering. Environ. Exp. Bot. 50, 79–85 10.1016/S0098-8472(03)00002-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich I. M., Hanzawa Y., Chou L., Roe J. L., Kover P. X., Purugganan M. D. (2009). Candidate gene association mapping of Arabidopsis flowering time. Genetics 183, 325–335 10.1534/genetics.109.105189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esashi Y., Maruyama A., Sasaki S., Tani T., Yoshiyama M. (1996). Involvement of cyanogens in the promotion of germination of cocklebur seeds in response to various nitrogenous compounds, inhibitors of respiratory and ethylene. Plant Cell Physiol. 37, 545–549 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S., Bielenberg D. G., Zhebentyayeva T. N., Reighard G. L., Okie W. R., Holland D., et al. (2010). Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with chilling requirement, heat requirement and bloom date in peach (Prunus persica). New Phytol. 185, 917–930 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust M., Erez A., Rowland L. J., Wang S. Y., Norman H. A. (1997). Bud dormancy in perennial fruit trees: physiological basis for dormancy induction, maintenance, and release. HortScience 32, 623–629 [Google Scholar]

- Flintoft L. (2008). Digging deep with RNA-Seq. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 413–413 10.1038/nrg2423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frehner M., Scalet M., Conn E. E. (1990). Pattern of the cyanide-potential in developing fruits. Plant Physiol. 94, 28–34 10.1104/pp.94.1.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George P., Lloyd A. J., Nissen R. J. (1992). Effects of hydrogen cyanamide, paclobutrazol and pruning date on dormancy release of the low chill peach cultivar Flordaprince in subtropical Australia. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 32, 89–95 10.1071/EA9920089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleadow R. M., Woodrow I. E. (2000). Temporal and spatial variation in cyanogenic glycosides in Eucalyptus cladocalyx. Tree Physiol. 20, 591–598 10.1093/treephys/20.9.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habu T., Yamane H., Igarashi K., Hamada K., Yano K., Tao R. (2012). 454-Pyrosequencing of the transcriptome in leaf and flower buds of Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc.) at different dormant stages. J. Japan Soc. Hort. Sci. 81, 239–250 10.2503/jjshs1.81.239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson U., West J., Lister C., Michaels S., Amasino R., Dean C. (2000). Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time. Science 290, 344–347 10.1126/science.290.5490.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C., Müller A. E. (2009). Flowering time control and applications in plant breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 563–573 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kester D. E. (1965). Inheritance of time of bloom in certain progenies of almond. Proc. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 87, 214–221 [Google Scholar]

- Kester D. E., Raddi P., Asay R. (1977). Correlation of chilling requirements for germination, blooming and leafing within and among seedling populations of almond. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 102, 145–148 [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. R. G., Ai X.-Y., Zhang J.-Z. (2014). Genetic regulation of flowering time in annual and perennial plants. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 5, 347–359 10.1002/wrna.1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke T., Schaeffer S., Harper A., Dicenta F., Edwards M., Henry R. J., et al. (2013). Comparative genomics analysis in prunoideae to identify biologically relevant polymorphisms. Plant Biotech. J. 11, 883–893 10.1111/pbi.12081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotoda N., Wada M., Kusaba S., Kano-Murakami Y., Masuda T., Soejima J. (2002). Overexpression of MdMADS5, an APETALA1-like gene of apple causes early flowering in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 162, 679–687 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00024-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leida C., Conejero A., Arbona V., Gómez-Cadenas A., Llácer G., Badenes M. L., et al. (2012). Chilling-dependent release of seed and bud dormancy in peach associates to common changes in gene expression. PLoS ONE 7:e35777 10.1371/journal.pone.0035777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., Zhebentyayeva T., Olukolu B., Wilde D., Reighard G. L., Abbott A. G. (2010). Comparison of gene order in the chromosome region containing a TERMINAL FLOWER 1 homolog in apricot and peach reveals microsynteny across angiosperms. Plant Sci. 179, 390–398 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Anderson J. M., Pijut P. M. (2010). Cloning and characterization of Prunus serotina AGAMOUS, a putative flower homeotic gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 28, 193–203 10.1007/s11105-009-0140-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gómez P., Crisosoto C., Bonghi C., Rubio M. (2011). New approaches to Prunus transcriptome analysis. Genetica 139, 755–769 10.1007/s10709-011-9580-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gómez P., Sánchez-Pérez R., Rubio M. (2012). Clarifying omics concepts, challenges and opportunities for Prunus breeding in the post-genomic era. OMICS: J. Integr. Biol. 16, 268–283 10.1089/omi.2011.0133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C. D., Leslie J. W., Frost H. B. (1952). Bitterness of kernels of almond × peach hybrids and their parents. Proc. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 59, 254–258 [Google Scholar]

- Mimida N., Li J., Zhang C., Moriya S., Moriya-Tanaka Y., Iwanami H., et al. (2012). Divergence of TERMINAL FLOWER1-like genes in Rosaceae. Biol. Plant. 56, 465–472 10.1007/s10535-012-0113-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morant A. V., Jørgensen K., Jørgensen C., Paquette S. M., Sánchez-Pérez R., Møller B. L., et al. (2008). β-Glucosidases as detonators of plant chemical defense. Phytochemistry 69, 1795–1813 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T., Suzuki K., Fujimura T., Shinshi H. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 140, 411–432 10.1104/pp.105.073783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogiso-Tanaka E., Matsubara K., Yamamoto S.-I., Nonoue Y., Wu J., Fujisawa H., et al. (2013). Natural variation of the RICE FLOWERING LOCUS T 1 contributes to flowering time divergence in rice. PLoS ONE 8:e75959 10.1371/journal.pone.0075959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olukolu B., Trainin T., Fan S., Kole C., Bielenberg D., Reighard G., et al. (2009). Genetic linkage mapping for molecular dissection of chilling requirement and budbreak in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Genome 52, 819–828 10.1139/G09-050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oracz K., El-Maarouf Bouteau H., Farrant J. M., Cooper K., Belghazi M., Job C., et al. (2007). ROS production and protein oxidation as a novel mechanism for seed dormancy alleviation. Plant J. 50, 452–465 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann J. L., Meyerowitz E. M. (1997). MADS domain proteins in plant development. Biol. Chem. 378, 1079–1101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos G., Leida C., Conejero A., Badenes M. L. (2014). Epigenetic regulation of bud dormancy events in perennial plants. Front. Plant Sci. 5:247 10.3389/fpls.2014.00247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez J., Sherman W. B., Scorza R., Wisniweski M., Okie W. R. (1994). ‘Evergreen’ peach, its inheritance and dormant behaviour. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 119, 789–792 [Google Scholar]

- Romeu J. F., Monforte A. J., Sánchez G., Granel A., García-Brunton J., Badenes M. L., et al. (2014). Quantitative trait loci affecting reproductive phenology in peach. BMC Plant Biol. 14:52 10.1186/1471-2229-14-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz D., Campoy J. A., Egea J. (2007). Chilling and heat requirements of apricot cultivars for flowering. Environ. Exp. Bot. 61, 254–263 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.06.00823053065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar J. A., Ruiz D., Egea J., Martínez-Gómez P. (2013). Inheritance of fruit quality traits in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) and analysis of linked quantitative trait loci (QTLs) using simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31, 1506–1517 10.1007/s11105-013-0625-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pérez R., Dicenta F., Martínez-Gómez P. (2012). Inheritance of chilling and heat requirements for flowering in almond and QTL analysis. Tree Genet. Genomes 8, 379–389 10.1007/s11295-011-0448-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pérez R., Howad D., Dicenta F., Arús P., Martínez-Gómez P. (2007b). Mapping major genes and quantitative trait loci controlling agronomic traits in almond. Plant Breed. 126, 310–318 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01329.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pérez R., Jørgensen K., Olsen C. E., Dicenta F., Møller B. L. (2008). Bitterness in almonds. Plant Physiol. 146, 1040–1052 10.1104/pp.107.112979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pérez R., Ortega E., Duval H., Martínez-Gómez P., Dicenta F. (2007a). Inheritance and correlation of important agronomic traits in almond. Euphytica 155, 381–391 10.1007/s10681-006-9339-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C., García-Mas J., Sánchez A. M., Arús P., Oliveira M. M. (2005). Looking into flowering time in almond (Prunus dulcis (Mill) D. A. Webb): the candidate gene approach. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110, 959–968 10.1007/s00122-004-1918-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socias i Company R., Felipe A. J. (1992). Almond: a diverse germplasm. HortScience 27, 718–863 [Google Scholar]

- Socias i Company R., Felipe A. J., Gómez-Aparisi J. (1999). A major gene for flowering time in almond. Plant Breed. 118, 443–448 10.1046/j.1439-0523.1999.00400.x15700145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano J. M., Vilanova S., Romero C., Llácer G., Badenes M. L. (2005). Characterization and mapping of NBS-LRR resistance gene analogs in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 110, 980–989 10.1007/s00122-005-1920-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanudakis E., Jackson S. (2014). The role of microRNAs in the control of flowering time. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 365–380 10.1093/jxb/ert453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka K.-I., Ohki I., Tsuji H., Kojima C., Shimamoto K. (2013). Structure and function of florigen and the receptor complex. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 287–294 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainin T., Holland D., Bar-Yaakov I. (2013). ParSOC1, a MADS-box gene closely related to Arabidopsis AGL20/SOC1, is expressed in apricot leaves in a diurnal manner and is linked with chilling requirements for dormancy break. Tree Genet. Genomes 9, 753–766 10.1007/s11295-012-0590-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkner C., Lehmann S., Hoenicka H., Hanke M. V., Fladung M., Lenhardt D., et al. (2010). Over-expression of an FT -homologous gene of apple induces early flowering in annual and perennial plants. Planta 232, 1309–1324 10.1007/s00425-010-1254-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verde I., Abbott A. G., Scalabrin S., Jung S., Shu S., Marroni F., et al. (2013). The high-quality draft of peach (Prunus persica) identifies unique patterns of genetic diversity, domestication and genome evolution. Nat. Genetics 45, 487–494 10.1038/ng.2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Karle R., Iezzoni A. F. (2000). QTL analysis of flower and fruit traits in sour cherry. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100, 535–544 10.1007/s001220050070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Zhang X., Yan G., Zhou Y., Zhang K. (2013). Over-expression of the PaAP1 gene from sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) causes early flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Physiol. 170, 315–320 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Pijut P. M. (2013). Isolation and characterization of a TERMINAL FLOWER 1 homolog from Prunus serotina Ehrh. Tree Physiol. 33, 855–865 10.1093/treephys/tpt051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H., Kashiwa Y., Ooka T., Tao R., Keizo Y. (2008). Suppression subtractive hybridization and differential screening reveals endodormancy-associated expression of an SVP/AGL24-type MADS-box gene in lateral vegetative buds of Japanese apricot. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 133, 708–716 [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H., Tao R., Ooka T., Jotatsu H., Sasaki R., Yonemori K. (2011). Comparative analyses of dormancy-associated MADS-box genes, PpDAM5 and PpDAM6, in low- and high-chill peaches (Prunus persica L.). J. Japan. Soc. Hort. Sci. 80, 276–283 10.2503/jjshs1.80.27621378115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhebentyayeva T. N., Fan S., Chandra A., Bielenberg D. G., Reighard G. L., Okie W. R., et al. (2014). Dissection of chilling requirement and bloom date QTLs in peach using a whole genome sequencing of silbling trees from a F2 mapping population. Tree Genet. Genomes 10, 35–51 10.1007/s11295-013-0660-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Xia R., Zhao B., An Y., Dardick C. D., Callahan A. M., et al. (2012). Unique expression, processing regulation, and regulatory network of peach (Prunus persica) miRNAs. BMC Plant Biol. 12:149 10.1186/1471-2229-12-149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang W., Gao Z., Wang L., Zhong W., Ni Z., Zhang Z. (2013). Comparative proteomic and transcriptomic approaches to address the active role of GA4 in Japanese apricot flower bud dormancy release. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 4953–4966 10.1093/jxb/ert284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]