Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoke contains compounds that may damage DNA, and the repair of damage may be impaired in women with germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. However, the effect of cigarette smoking on breast cancer risk in mutation carriers is the subject of conflicting reports. We have examined the relation between smoking and breast cancer risk in non-Hispanic white women under the age of 50 years who carry a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2.

Methods

We conducted a case-control study using data from carriers of mutations in BRCA1 (195 cases and 302 controls) and BRCA2 (128 cases and 179 controls). Personal information, including smoking history, was collected using a common structured questionnaire by eight recruitment sites in four countries. Odds-ratios (OR) for breast cancer risk according to smoking were adjusted for age, family history, parity, alcohol use, and recruitment site.

Results

Compared to non-smokers, the OR for risk of breast cancer for women with five or more pack-years of smoking was 2.3 (95% confidence interval 1.6–3.5) for BRCA1 carriers and 2.6 (1.8–3.9) for BRCA2 carriers. Risk increased 7% per pack-year (p < 0.001) in both groups.

Conclusions

These results indicate that smoking is associated with increased risk of breast cancer before age 50 years in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. If confirmed, they provide a practical way for carriers to reduce their risks. Previous studies in prevalent mutation carriers have not shown smoking to increase risk of breast cancer, but are subject to bias, because smoking decreases survival after breast cancer.

Keywords: BRCA1, BRCA2, Smoking, Breast cancer risk

Introduction

Cigarette smoking has biological effects that suggest it may either increase or decrease risk of breast cancer. Mutagens in cigarette smoke, such as polycyclic hydrocarbons, aromatic amines, and N-nitrosamines, may increase risk. Animal experiments show that exposure to these compounds may increase risk of mammary tumors, and DNA adducts with some of these compounds have been found in the breast tissue of smokers, as well as in the tumors of smokers with breast cancer [1]. Smoking may decrease risk of breast cancer by reducing exposure to estrogen. Compared to non-smokers, smokers have been shown to have lower luteal-phase urinary estrogen levels, an earlier menopause, less body fat, a decreased risk of endometrial cancer, and an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture [2–5].

The epidemiological evidence on the association of smoking with risk of breast cancer is contradictory. Terry and Rohan in 2002 reviewed the published evidence and concluded that smoking probably did not decrease, and may increase, risk of breast cancer [6]. A combined re-analysis of 53 epidemiological studies, however, did not show smoking to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer after alcohol use was taken into account [7]. In a meta-analysis in 2005, Johnson found that both active and passive smoking were associated with an increased risk of premenopausal breast cancer [8].

The biological effects of smoking suggest that genetic variations in acetylation, oxidative damage, and DNA repair, may influence risk of disease. For example, high levels of reactive oxygen species may cause single and double strand breaks. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are involved in the repair of such breaks [9], and mutations in these genes may impair the ability of carriers to repair any defects caused by smoking.

Lifetime risks of breast cancer among carriers of deleterious mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been estimated at 40–80% [10–12]. Because 20–60% of carriers live to an advanced age, and do not develop breast cancer, there are likely to be other genetic or environmental factors that modify risk. The purpose of the present study was to examine the effects of cigarette smoking on breast cancer risk in a large number of affected (cases) and unaffected (controls) members of families segregating mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

Methods

General method

The study is case-control in design, and uses data from carriers of mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, affected (cases) and unaffected (controls) by breast cancer, from whom information on personal attributes, including smoking history, was collected using a common structured questionnaire. Details of the methods used have been given elsewhere and are summarized here [13,14].

Participating subjects and sites

Eligible subjects were living non-Hispanic white women aged less than 50 years who carried a deleterious mutation in either BRCA1 or BRCA2 and were ascertained from the Breast Cancer Family Registry (Breast CFR), a consortium of research groups in the United States, Australia, and Canada [15], the Kathleen Cuningham Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer (kConFab), Australia and New Zealand (Australasia) [16], and the Ontario Cancer Genetics Network (OCGN), Canada. All sites collected pedigree and epidemiologic risk factor data and biospecimens. Subjects with a first primary invasive breast cancer were defined as cases, and unaffected subjects were defined as controls. Because the effects of risk factors for breast cancer may differ according to menopausal status, and there were few subjects over the age of 50, we included only women aged less than 50 years.

Family ascertainment

The methods used to ascertain families that are the source of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers have been described previously [13], and will be summarized briefly here. Three approaches were used. Breast CFR groups in San Francisco, Ontario, and Australia ascertained families through women with incident breast cancer who were sampled from a population-based cancer registry (probands). In San Francisco and Ontario, cases with a family history of cancer were over-sampled, whereas in Australia all incident cases were included in the registry. Breast CFR groups in New York, Philadelphia, Utah, and Australia, as well as kConFab (in Australia and New Zealand) and OCGN, ascertained multiple-case families through cancer family clinics, selecting probands according to minimum family history criteria. In addition, Ashkenazi Jewish families were ascertained by Breast CFR groups in New York, Philadelphia, Ontario, and Australia by community outreach efforts.

All participants were asked to permit researchers to contact their first-degree relatives, from whom demographic and epidemiologic data and blood samples were also obtained. All relevant institutional review boards approved the study protocol and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Personal characteristics

Data on smoking, alcohol consumption, oral contraceptive (OC) use, and reproductive and other risk factors were obtained from all subjects using the same structured questionnaire. Data were obtained by personal interview whenever possible, or by telephone when necessary, except in Utah and Ontario where data were obtained by mailed questionnaires supplemented by telephone calls. All smoking information referred to smoking before the reference date (the date of breast cancer diagnosis for cases, and as defined below in Sect. “Statistical analysis” for controls). Questions about smoking included whether the subject had ever smoked at least one cigarette per day for 3 months or longer, the ages at which smoking was started and stopped, cumulative duration of cigarette smoking, and the average daily number of cigarettes smoked.

Identification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers

The proband in the population-based families was tested first for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. For the clinic-based families, the woman in the family diagnosed with breast cancer at the youngest age was in general selected for testing first, and relatives evaluated if a mutation was found. All participants of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry were tested for the three Ashkenazi founder mutations. The methods used to identify mutations are described elsewhere [13,14], as is a comparison of these methods with full gene sequencing [17].

Statistical analyses

Each subject was assigned a reference age. For subjects with invasive breast cancer (cases) this was age at diagnosis, and for those not affected by invasive breast cancer (controls) the age at the earliest of the following events: interview, bilateral mastectomy, bilateral oophorectomy, or diagnosis of in-situ breast cancer. To minimize survival bias and recall bias, we restricted analysis to subjects interviewed no more than 5 years after their reference age. Approximately 82% of subjects were interviewed within 3 years of their reference age. The following exposure measures were created: categories of smoking (never, former, current), and cigarette pack-years (number of years smoked times the average number of cigarettes per day, divided by 20).

We used unconditional logistic regression implemented in SAS (SAS 2000) to compare smoking histories in cases and controls. Odds-ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated by modeling the probability distribution of attributes of ascertained carriers, conditional on reported pedigree structure and family disease occurrences. Logistic regression provides consistent OR estimates under a marginal covariate model, with intra-family attribute correlations accommodated by a robust variance estimator [18]. This approach accommodates the possibility that carriers may have been ascertained because of their breast cancer status [18].

All regression models included reference age as a discrete variable (<40 years, 40–49 years) and a continuous variable, number of full-term pregnancies (0,1−2,3+), alcohol intake (drink-years), family history (yes, no) of breast or ovarian cancer in one or more first-degree relatives, and study site (Australasia, Canada, New York, Philadelphia, Utah, Northern California). Since we adjusted for reference age and subjects were ascertained in a short time period there was no need to adjust for year of birth. To control for the influence of occasional large values on tests of trend with continuous variables, we first categorized variables, and then replaced the reported values in each category by the median for that category. We also examined the effect of smoking at an early age (≤20 years, > 20 years), and smoking before first full-term pregnancy, and tested for an interaction between smoking and parity. Finally, we conducted separate analyses of the clinic-based data alone and the population-based data alone. Results were generally similar between these series of subjects so we report here results from the combined analyses.

Results

Characteristics of subjects and prevalence of smoking

Selected characteristics of 195 affected (cases) and 302 unaffected women (controls) with mutations in BRCA1, and 128 affected and 179 unaffected women with mutations in BRCA2, are shown in Table 1. On average, women with breast cancer were slightly older than unaffected controls at reference age. A similar number of cases and controls were recruited from Australasia and the United States (except Utah), but there were relatively more cases than controls from Canada, and more controls than cases from Utah. About two thirds of the cases were recruited through clinics.

Table 1. Characteristics of non-Hispanic white BRCA mutation carriers with and without invasive breast cancer for women less than 50 years of age, by mutation status.

| BRCA1 mutation carriers | BRCA2 mutation carriers | Combined mutation carriers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Affected (cases)d (n = 195) N (%) | Unaffected (controls) (n = 302) N (%) | Affected (cases)d (n = 128) N (%) | Unaffected (controls) (n = 179) N (%) | Affected (cases)d (n = 323) N (%) | Unaffected (controls) (n = 481) N (%) | |

| Reference age (years)a | ||||||

| <30 | 23 (12) | 80 (27) | 10 (8) | 34 (19) | 33 (10) | 114 (24) |

| 30–39 | 88 (45) | 107 (35) | 61 (48) | 60 (34) | 149 (46) | 167 (35) |

| 40–49 | 84 (43) | 115 (38) | 57 (44) | 85 (47) | 141 (44) | 200 (41) |

| Year of birth | ||||||

| 1940–1949 | 16 (8) | 30 (10) | 16 (13) | 34 (19) | 32 (10) | 64 (13) |

| 1950–1959 | 103 (53) | 87 (29) | 61 (48) | 53 (30) | 164 (51) | 140 (29) |

| 1960–1969 | 65 (33) | 98 (32) | 49 (38) | 56 (31) | 114 (35) | 154 (32) |

| 1970+ | 11 (6) | 87 (29) | 2 (1) | 36 (20) | 13 (4) | 123 (26) |

| Site | ||||||

| Australasia | 91 (47) | 121 (40) | 65 (51) | 91 (51) | 156 (48) | 212 (44) |

| Canada | 47 (24) | 15 (5) | 35 (27) | 13 (7) | 82 (25) | 28 (6) |

| United States | ||||||

| NCCC | 13 (7) | 3 (1) | 9 (7) | 5 (3) | 22 (7) | 8 (2) |

| New York | 17 (9) | 45 (15) | 9 (7) | 21 (12) | 26 (8) | 66 (14) |

| Philadelphia | 12 (6) | 33 (11) | 4 (3) | 17 (10) | 16 (5) | 50 (10) |

| Utah | 15 (8) | 85 (28) | 6 (5) | 32 (18) | 21 (7) | 117 (24) |

| Source of data | ||||||

| Clinic-based | 120 (62) | 284 (94) | 76 (59) | 158 (88) | 196 (61) | 442 (92) |

| Population-based | 75 (38) | 18 (6) | 52 (41) | 21 (12) | 127 (39) | 39 (8) |

| Family historyb | ||||||

| Yes | 114 (58) | 229 (76) | 67 (52) | 127 (71) | 181 (56) | 356 (74) |

| No | 81 (42) | 73 (24) | 61 (48) | 52 (29) | 142 (44) | 125 (26) |

| Number of full-term pregnanciesc | ||||||

| 0 | 49 (25) | 102 (34) | 27 (21) | 37 (21) | 76 (24) | 139 (29) |

| 1–2 | 99 (51) | 114 (38) | 64 (50) | 82 (46) | 163 (51) | 196 (41) |

| ≥3 | 46 (24) | 85 (28) | 37 (29) | 60 (33) | 83 (26) | 145 (30) |

| Menopausal status | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 156 (91) | 260 (94) | 111 (92) | 152 (93) | 267 (95) | 412 (94) |

| Postmenopausal | 16 (9) | 15 (6) | 9 (8) | 12 (7) | 15 (5) | 27 (6) |

| Ever use of alcohol | ||||||

| Yes | 95 (49) | 123 (42) | 68 (53) | 93 (52) | 163 (51) | 216 (45) |

| No | 100 (51) | 179 (58) | 60 (47) | 86 (48) | 160 (49) | 265 (55) |

For cases, age at breast cancer diagnosis and for controls, age at the earliest of these events: bilateral mastectomy, bilateral oophorectomy, diagnosis of in-situ breast cancer, or interview

One of more first-degree relatives with breast or ovarian cancer

Live births and stillbirths

The totals for the different variables may not equal to the total number of subjects in a category because of missing data

Unaffected women who served as controls were derived from breast cancer family registries, and as a result more often had a family history of the disease than did women affected by breast cancer who served as cases. As only subjects aged less than 50 years were included, most were premenopausal. Use of alcohol was slightly more frequent among cases than controls, but this difference was not significant. Eighty (10%) of the 804 subjects were members of the same families. The mean interval between diagnosis and interview in cases was 2.0 years (SD = 1.47 years), and 82% were interviewed within 3 years of diagnosis.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of smoking in cases and controls according to recruitment site and mutation. In all sites, among BRCA1 mutation carriers, more controls than cases had never smoked, and there were more current smokers at reference age among cases than controls in all sites except Philadelphia. Findings were similar among BRCA2 mutation carriers, with the exceptions of Philadelphia and Utah, where there were few subjects. In the combined mutation carriers, the prevalence of current smokers among women affected by breast cancer varied from 28% in Australasia to 10% in Utah, and among controls from 21% in Australasia to 3% in Utah. In the combined data, current smoking was more frequent among cases than controls for all sites except Philadelphia.

Table 2. Prevalence of smoking among women less than 50 years of age, according to recruitment site and BRCA mutation status.

| Site | Smoking status | BRCA1 mutation carriers | BRCA2 mutation carriers | Combined mutation carriers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Affected (cases) N (%) | Unaffected (controls) N (%) | Affected (cases) N (%) | Unaffected (controls) N (%) | Affected (cases) N (%) | Unaffected (controls) N (%) | ||

| Australasia | Never | 39 (44) | 64 (54) | 29 (46) | 51 (56) | 68 (45) | 115 (55) |

| Former | 20 (23) | 26 (22) | 21 (33) | 25 (28) | 41 (27) | 51 (24) | |

| Currenta | 30 (34) | 28 (24) | 13 (21) | 15 (16) | 43 (28) | 43 (21) | |

| Canada | Never | 23 (49) | 10 (67) | 13 (37) | 10 (77) | 36 (44) | 20 (71) |

| Former | 12 (26) | 2 (13) | 15 (43) | 2 (15) | 27 (33) | 4 (14) | |

| Currenta | 12 (26) | 3 (20) | 7 (20) | 1 (8) | 19 (23) | 4 (14) | |

| United States | |||||||

| NCCC | Never | 10 (77) | 3 (100) | 4 (44) | 3 (60) | 14 (64) | 6 (75) |

| Former | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 (44) | 2 (40) | 5 (23) | 2 (25) | |

| Currenta | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | |

| New York | Never | 9 (53) | 27 (60) | 3 (33) | 11 (55) | 12 (46) | 38 (59) |

| Former | 4 (24) | 14 (31) | 3 (33) | 8 (40) | 7 (27) | 22 (34) | |

| Current | 4 (24) | 4 (9) | 3 (33) | 1 (5) | 7 (27) | 5 (8) | |

| Philadelphia | Never | 7 (58) | 18 (64) | 3 (75) | 12 (71) | 10 (63) | 30 (67) |

| Former | 3 (25) | 4 (14) | 1 (25) | 2 (12) | 4 (25) | 6 (13) | |

| Current | 2 (17) | 6 (21) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | 2 (13) | 9 (20) | |

| Utah | Never | 12 (80) | 71 (88) | 6 (100) | 30 (94) | 18 (86) | 101 (89) |

| Former | 1 (7) | 7 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 1 (5) | 9 (8) | |

| Currenta | 2 (13) | 3 (4) | – | – | 2 (10) | 3 (3) | |

NCCC Northern California Cancer Center

At reference age

Smoking and breast cancer risk

Table 3 shows the OR for breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers according to smoking status, and adjusted for age, site, number of full term pregnancies, family history, and alcohol use. Compared with never smokers, risk was increased for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers who were current smokers at their reference age. Risk was increased more than twofold for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers who were current smokers at their reference age, or for those with at least 5 pack-years of smoking. There was a statistically significant trend of increasing relative risk with increasing duration of smoking, with an estimated average 7% increase per pack-year of smoking for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Table 3. Risk of invasive breast cancer among BRCA mutation carriers according to smoking history for women less than 50 years of age, by BRCA mutation status.

| BRCA1 mutation carriers | BRCA2 mutation carriers | Combined mutation carriers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Affected (cases)c (n = 195) N (%) | Unaffected (controls)c (n = 302) N (%) | OR | 95% CI | Affected (cases)c (n = 128) N (%) | Unaffected (controls)c (n = 179) N (%) | OR | 95% CI | Affected (cases)c (n = 323) N (%) | Unaffected (controls)c (n = 481) N (%) | OR | 95% CI | |

| Smoking statusa | ||||||||||||

| Never | 100 (52) | 193 (67) | 1.0 | – | 58 (46) | 117 (66) | 1.0 | – | 158 (49) | 310 (66) | 1.0 | – |

| Former | 41 (21) | 53 (18) | 144 | 0.96–2.17 | 44 (35) | 41 (23) | 2.02 | 1.37–2.96 | 85 (27) | 94 (20) | 1.67 | 1.26–2.22 |

| Currentb | 52 (27) | 44 (15) | 2.02 | 1.31–3.10 | 24 (27) | 20 (11) | 2.35 | 1.25–4.43 | 76 (24) | 64 (14) | 2.08 | 1.41–3.06 |

| Pack-years of smokinga | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 100 (52) | 193 (67) | 1.0 | – | 58 (46) | 117 (66) | 1.0 | – | 158 (49) | 310 (66) | 1.0 | – |

| 1–4 | 27 (14) | 48 (17) | 1.06 | 0.64–1.74 | 27 (21) | 31(17) | 1.67 | 1.00–2.79 | 54 (18) | 79 (18) | 1.30 | 0.93–1.82 |

| ≥5 | 62 (34) | 46 (16) | 2.33 | 1.56–3.47 | 41 (34) | 30 (17) | 2.64 | 1.78–3.90 | 103 (33) | 76 (16) | 2.38 | 1.79–3.17 |

| Trend per pack-year | – | – | 1.07 | p < 0.001 | – | – | 1.07 | p < 0.001 | – | – | 1.07 | p < 0.001 |

OR odds-ratio, CI confidence interval

Adjusted for age (see Sect. “Methods”), study site (Australasia, Canada, New York, Philadelphia, Utah, Northern California), number of full-term pregnancies (0,1–2,3+), alcohol use (drink-years) and history of breast or ovarian cancer in a first-degree relatives (yes, no)

At reference age

The totals for the different variables do not always equal to the total number of subjects in the case or control category because of missing data

Because of evidence that smoking influences survival in breast cancer (see Sect. “Discussion”), we examined the potential influence on these results of the inclusion of prevalent cases. We repeated all analyses including only cases interviewed within 3 years of diagnosis, in whom the average interval between diagnosis and interview was 1.44 years (SD = 0.92 years). The results were unchanged (data not shown). Because of the very low prevalence of smoking in Utah, in addition to adjusting for site in the analyses shown, we also repeated all analyses after the exclusion of cases and controls from that state. The results were again unchanged (data not shown).

After controlling for smoking duration, there was no evidence that smoking at an early age, or smoking before first pregnancy, had any additional effect on risk (data not shown).

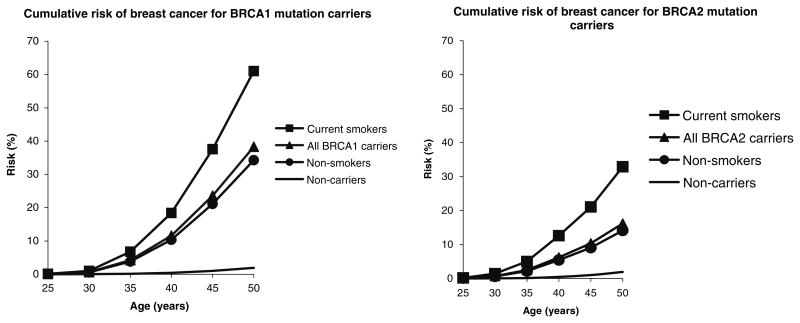

Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence of breast cancer to age 50 years in smokers and non-smokers, based on our estimated relative risk associated with smoking, and the pooled estimates of cumulative risk from Antoniou et al [19]. For BRCA1 carriers, we predict that 60% of smokers will develop breast cancer by age 50 years, compared to about 35% of non-smokers. For BRCA2 carriers, we predict that 35% of smokers will develop the disease by age 50 years, compared to about 15% of non-smokers.

Fig. 1.

Estimated cumulative incidence of breast cancer to age 50 in carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Cumulative incidence estimated by combining age-specific incidence data among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (5) with the smoking prevalence among controls of Table 2 and the odds-ratio estimates of Table 3

Discussion

These results show that a history of ever smoking is associated with a marked increase in risk of breast cancer before age 50 years in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. In both groups of mutation carriers there was, after adjustment for family history, parity, alcohol use, and recruitment site, an average increase in breast cancer risk of 7% for each additional pack-year of smoking. We estimate that smoking about doubles the cumulative incidence of breast cancer by age 50 years in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Because these results are based on a history of ever smoking, they are not influenced by any tendency of affected individuals or unaffected family members to quit smoking after a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Five previous studies have examined the effect of smoking on breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, and selected characteristics and results of these studies are shown in Table 4, together with the present study [20–23]. Brunet et al. [20], Colilla et al. [23], and Nkondjock et al. [24], found a reduced risk of breast cancer in smokers with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations that was statistically significant in the first two of these studies. However, the study by Ghadirian et al. [21], that included data from Brunet et al. and a study by Gronwald et al. found that smoking had no effect on risk of breast cancer in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations [22].

Table 4. Selected characteristics of studies on smoking and breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

| Variable | Brunet [20] | Ghadirian [21] | Gronwald [22] | Colilla [23] | Nkondjock [24] | Present study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (average in years) | 49.7 | 48.9 | 43.9 | 45–55 | 56 | 39 |

| Number of centers | 15 | 52 | 1 | 5 | 9 | |

| Number of cases | 186 | 1,097 | 348 | 176 | 89 | 323 |

| Number of controls | 186 | 1,097 | 348 | 140 | 48 | 481 |

| Genotyping | Various-confirmed by sequencing | Not stated | BRCA1 “Polish founder” mutations | Not stated | 19 “French Canadian” mutations | Site specific – standardised |

| Measures of smoking | N, E, PPW, PY | N, E, PY | N, P, C | N, E, PY | N, E, PY | N, F, C, PY |

| Prevalence of ever smoking—cases | 39% | 41% | 46% | 45% | 49% | 51% |

| Prevalence of ever smoking—controls | 52% | 40% | 46% | 50% | 54% | 34% |

| OR for ever vs never smoked | 0.57 (0.4,0.9) | 1.05 (0.9, 1.2 | ) 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 0.63 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.85 (0.4, 1.7)a | 1.76 (1.4, 2.3) |

| Interval between diagnosis and interview or genetic testing | w Average 8 years | Average 8.9 years | Average 3.2 years | Median 10–15 years | Not statedb | Average 2 years |

N never smoked, E ever smoked, F former smoker, C current smoker, PY pack-years, PPW packs per week

Unadjusted odds-ratio calculated by present author from data in Table 1 of reference 26

Subjects recruited since 1995, 11 years before publication

The results of the present study differ from all of the others shown in the table because the prevalence of smoking was higher among cases and lower among controls. As shown in Table 2, in the present study women affected by breast cancer were more often smokers than unaffected controls in two of three clinic-based sites, and all three population-based sites, and in each of the three countries, from which we recruited.

Baron and Haile, in an editorial that commented on the paper by Brunet et al., pointed out that use of prevalent cases, convenience samples of cases and controls, and possible bias in the selection of subjects for genetic testing, may affect interpretation of the results [25]. Of these potential sources of bias, the use of prevalent cases, interviewed or tested for mutations many years after diagnosis, appears most likely to explain differences in results between the present and previous studies, because, as described below, smoking adversely affects survival after breast cancer. Because of the preferential loss of women who smoke, the inclusion of prevalent cases may bias results toward null, or even show apparently protective effects of smoking, in the face of a true underlying increase in risk associated with smoking [26].

In the American Cancer Society prospective study of adult women, Calle et al. found that smoking was associated with an increased risk of fatal breast cancer (RR 1.26, 95% CI = 1.05–1.50), that increased with number of cigarettes and number of years smoked [27]. Yu et al. found a relative risk of death from breast cancer of 1.40 (95% CI = 1.0–1.9) associated with smoking, after adjustment for tumor characteristics and other potential confounders [28]. Manjer et al. found that the relative risk of death from breast cancer was 2.14 (95% CI = 1.47–3.10) in current smokers, after adjustment for age and stage and other potential confounders [29]. Scanlon et al. found that, after adjustment for age, stage, and body weight, those with more than 20,000 packs over their lifetime had a relative risk of lung metastases of 3.73 (95% CI = 1.6–8.9) compared to non-smokers [30]. Fentiman et al. found in women with stage I–II breast cancer that, after age and stage, smoking was the most important predictor of breast cancer specific and overall survival. The hazard ratio for distant relapse-free survival for current smokers compared to non-smokers was 1.67 (95% CI = 0.92–3.03) [31].

Because smokers with breast cancer are more likely to die than non-smokers with the disease, smokers will be underrepresented among women studied many years after the diagnosis of breast cancer. As a result studies that include prevalent cases, where survival to the initiation of the study is required, are subject to prevalence/incidence (Neyman's) bias [26], and a true underlying association of smoking with an increased risk of breast cancer may not be seen, or smoking may appear to be protective against breast cancer. As is shown in Table 4, three of the five previous studies had an average interval between diagnosis and testing or interview of at least 8 years [20, 21, 23], and one an interval of 3 years[22]. A fifth study did not specify the years of diagnosis, interview or testing, but did state that subjects were recruited since 1995, 11 years before the date of publication, and may also have included prevalent cases [24].

The present study also included prevalent cases, but none were more than 5 years after diagnosis, and the mean interval from diagnosis to testing or interview was 2 years, SD = 1.47). This short interval reduces, but does not entirely remove, the potential bias created by the effect of smoking on survival. Restricting the analysis to those diagnosed within 3 years of testing or interview, in whom the mean interval from diagnosis to testing or interview was 1.44 years (SD = 0.92 years), did not change the results.

Cohort studies, in which smoking and the identification of mutation status precede the development of breast cancer, are not subject to prevalence/incidence bias, and a number of cohort studies have now shown that smoking is associated with an increased risk of breast. Of 11 cohort studies included in the Terry and Rohan review [6], ORs of breast cancer in smokers were greater than unity in eight of them, and statistically significant in two of these. In another two the lower bound of the CI was exactly 1.0. Since this review, The Nurses Health Study [32], The California Teachers Study [33], and a cohort study in Norway and Sweden [34] have all found that smoking increased risk of breast cancer. Further, in a historical cohort of families at high risk for breast cancer, the sisters and daughters of affected probands who had ever smoked were at a 2.4-fold increased risk of breast cancer, compared to non-smokers (95% CI = 1.2–5.1) [35], a result that is similar to the present study. No cohort study has yet been carried out in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

While the results of the present study need confirmation, preferably in large prospective cohort studies, they indicate the potentially important influence of an environmental exposure on genetically determined increased susceptibility to breast cancer, and suggest a practical means by which women with inherited susceptibility may reduce their risk.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute under RFA #CA-95-003, and through cooperative agreements with the University of Melbourne, Northern California Cancer Center, Cancer Care Ontario, the Fox Chase Cancer Center, Huntsman Cancer Institute, and Columbia University as part of the Breast Cancer Family Registry (Breast CFR), and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA097359, PI: Dr A Whittemore). The Kathleen Cuningham Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer is supported by the National Breast Cancer Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, and The Cancer Councils of Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia, South Australia, and Victoria. Prof. Hopper is a NHMRC Principal Research Fellow and a Victorian Breast Cancer Research Consortium Group Leader. Dr Boyd is supported by the Lau Chair in Breast Cancer Research.

References

- 1.Perera FP, Estabrook A, Hewer A. Carcinogen-DNA adducts in human breast tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4(3):233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron JA, La Vecchia C, Levi F. The antiestrogenic effect of cigarette smoking in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162(2):502–514. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90420-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesko SM, Rosenberg L, Kaufman DW, Helmrich SP, Miller DR, Strom BL. Cigarette smoking and the risk of endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(10):593–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509053131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams AR, Weiss NS, Ure CI, Ballard J, Daling JR. Effect of weight, smoking, and estrogen use on the risk of hip and forearm fractures in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60(6):695–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacMahon B, Trichopoulos D, Cole P. Cigarette smoking and urinary estrogens. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(17):1062–1065. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198210213071707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terry PD, Rohan TE. Cigarette smoking and the risk of breast cancer in women: a review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(10 Pt 1):953–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer—collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(11):1234–1245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KC. Accumulating evidence on passive and active smoking and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(4):619–628. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern MC, Umbach DM, van Gils CH, Lunn RM, Taylor JA. DNA repair gene XRCC1 polymorphisms, smoking, and bladder cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(2):125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, et al. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(20):1401–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705153362001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorlacius S, Struewing JP, Hartge P. Population-based study of risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA2 mutation. Lancet. 1998;352(9137):1337–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopper JL, Southey MA, Dite GS, et al. Population-based estimate of the average age-specific cumulative risk of breast cancer for a defined set of protein-truncating mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Australian Breast Cancer Family Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(9):741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haile RW, Thomas DC, McGuire V, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, oral contraceptive use and breast cancer before age 50. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;0(0):0. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire V, John EM, Felberg A, et al. No increased risk of breast cancer associated with alcohol consumption among carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations ages < 50 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(8):1565–1567. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John EM, Hopper JL, Beck JC, et al. An infrastructure for cooperative multinational, interdisciplinary and translational studies of the genetic epidemiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(4):R375–R389. doi: 10.1186/bcr801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann GJ, Thorne H, Balleine RL, et al. Analysis of cancer risk and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence in the kConFab familial breast cancer resource. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(1):R12. doi: 10.1186/bcr1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrulis IL, Anton-Culver H, Beck J, et al. Comparison of DNA- and RNA-based methods for detection of truncating BRCA1 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2002;20(1):65–73. doi: 10.1002/humu.10097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittemore AS, Halpern J. Logistic regression of family data from retrospective study designs. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25(3):177–189. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(5):1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunet JS, Ghadirian P, Rebbeck T, et al. Effect of smoking on breast cancer in carriers of mutant BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(1):761–765. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.10.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghadirian P, Lubinski J, Lynch H, et al. Smoking and the risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA mutations. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(3):413–416. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gronwald J, Byrski T, Huzarski T, et al. Influence of selected lifestyle factors on breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers from Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95(2):105–109. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colilla S, Kantoff PW, Neuhausen SL, et al. The joint effect of smoking and AIB1 on breast cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(3):599–605. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nkondjock A, Robidoux A, Paredes Y, Narod SA, Ghadirian P. Diet, lifestyle and BRCA-related breast cancer risk among French–Canadians. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98(3):285–294. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron JA, Haile RW. Protective effect of cigarette smoking on breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(10):726–727. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.10.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sackett D. Bias in analytic research. J Chron Dis. 1979;32(1–2):51–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calle EE, Miracle-McMahill HL, Thun MJ, Heath CW., Jr Cigarette smoking and risk of fatal breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139(10):1001–1007. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu GP, Ostroff JS, Zhang ZF, Tang J, Schantz SP. Smoking history and cancer patient survival: a hospital cancer registry study. Cancer Detect Prev. 1997;21(6):497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manjer J, Andersson I, Berglund G, et al. Survival of women with breast cancer in relation to smoking. Eur J Surg. 2000;166(11):852–858. doi: 10.1080/110241500447227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scanlon EF, Suh O, Murthy SM, Mettlin C, Reid SE, Cummings KM. Influence of smoking on the development of lung metastases from breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;75(11):2693–2699. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950601)75:11<2693::aid-cncr2820751109>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fentiman IS, Allen DS, Hamed H. Smoking and prognosis in women with breast cancer. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(9):999–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Delaimy WK, Cho E, Chen WY, Colditz G, Willet WC. A prospective study of smoking and risk of breast cancer in young adult women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(3):398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds P, Hurley S, Goldberg DE, et al. Active smoking, household passive smoking and breast cancer: evidence from the California teachers study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(1):29–37. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gram IT, Braaten T, Terry PD, et al. Breast cancer risk among women who start smoking as teenagers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(1):61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Couch FJ, Cerhan JR, Vierkant RA, et al. Cigarette smoking increases risk for breast cancer in high-risk breast cancer families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(4):327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]