Abstract

Purpose

To examine the association of smoking and quality of life (QOL) among survivors of breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancers.

Methods

The study included women who joined the Iowa Women’s Health Study in 1986 and were subsequently diagnosed with breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancers through 2004 (n=1920). Smoking status was reported at baseline and in 2004; QOL was assessed in 2004 using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36. Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios were calculated to examine the associations of smoking status and poor QOL (score lower than one-half a standard deviation below the mean of the non-smokers).

Results

Compared with non-smokers, persistent smokers had higher likelihood of reporting poor Physical Functioning (odds ratio [OR] = 2.40, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.32–4.37), Mental Health (OR = 1.92, CI = 1.09–3.40), and Role Emotional (OR = 2.01, CI = 1.10–3.66), whereas former smokers had higher likelihood of reporting poor Physical Functioning (OR = 1.65, CI = 1.10–2.45), Mental Health (OR = 1.62, CI = 1.11–2.37), and General Health (OR = 1.51, CI = 1.03–2.21). A statistically significant trend toward higher likelihood of poor QOL was observed across smoking groups in Vitality, Physical Functioning, Mental Health, and Role Emotional. Further adjustment for physical activity resulted in attenuation of the odds ratios and p-values for trend.

Conclusion

Among women with breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancers, smokers were more likely than former or non-smokers to have poor QOL. Physical activity explained, in part, the association between smoking status and QOL in our study.

Keywords: cancer survivors, smoking, quality of life, physical activity, SF-36

INTRODUCTION

Smoking is a risk factor for many types of cancer, including cancers of the lung, bladder, esophagus, stomach, kidney, cervix, pancreas, and head and neck.1 In addition, many studies suggest that smoking may reduce the effectiveness of cancer therapies and increase the risk of developing a second primary cancer.2 Evidence has also emerged that suggests smoking can affect the quality of life (QOL) of cancer patients. A cross-sectional study of head and neck cancer patients found that current smokers experienced significantly poorer physical functioning, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, and emotional functioning compared with nonsmokers.3 In prospective cohort studies, adverse effects on QOL were consistently noted in head and neck cancer patients who continued smoking after diagnosis.4, 5 Among newly diagnosed lung cancer patients, persistent smokers reported significantly lower QOL compared with never smokers and moderately lower QOL compared with former smokers or those patients who quit between diagnosis and subsequent evaluation.6 These results are consistent with associations observed in the general population that show nonsmokers with the highest QOL followed by former and then current smokers.7– 10

One important shortcoming of the evidence of the negative impact of smoking on QOL among cancer survivors is that these data are derived from studies done in populations with smoking-related cancers including cancers of the lung and head and neck. Also these studies included relatively young population with short follow up after cancer diagnosis. 3–5 Although survivors of breast, colorectal and endometrial cancers represents majority among females, relatively less is known about the association between smoking status and QOL in this population. The present study compared QOL among non-smokers, former smokers, and persistent smokers diagnosed with breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancers using data collected from participants in a large prospective cohort study of cancer incidence in postmenopausal women.

METHODS

Study population

The Iowa Women’s Health Study (IWHS) is a population-based, prospective cohort study launched in 1986 to examine whether diet, body fat distribution, or other potential risk factors were associated with cancer incidence in postmenopausal women. Detailed methods for the IWHS have been described previously.11 In brief, a self-administered questionnaire was sent to 99,826 women, ages 55 to 69, randomly selected from the Iowa driver’s license database in 1986. The questionnaire was completed by 41,836 women (42%), with five follow-up questionnaires sent in 1987, 1989, 1992, 1997, and 2004. Demographic and lifestyle information was collected including smoking status, prior health conditions, and anthropometrics; quality of life was measured in 2004. The vital status (living or deceased) of non-responders to follow-up surveys was determined though the National Death Index. The IWHS was approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board.

Incident cancers diagnosed within the IWHS cohort were ascertained between 1986 and 2004 by linkage to the State Health Registry of Iowa, which participates in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. After excluding 1,511 women who reported a cancer diagnosis at baseline, 40,325 women were prospectively followed for cancer occurrence. A total of 4,328 women developed incident breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancer (the three cancer types eligible for this study) from 1986 to 2004. For the purpose of this analysis, women with one of these three cancers were classified as respondents if they completed the questionnaire in 2004 (n=1,949), as deceased participants if they died prior to 2004 (n=1,389), and as non-respondents if they failed to return the 2004 questionnaire (n=796) or did not complete the QOL section of the 2004 questionnaire (n= 193) or if their 2004 questionnaire was completed by proxy (n=1).

The questionnaires sent to participants in 1986 and 2004 included the question, “Do you smoke cigarettes now?” Of the 1,949 respondents, 1,928 women answered this question in both 1986 and 2004. Based on their response, participants were classified as non-smokers if they answered “no” in both 1986 and 2004 (n=1,720), former smokers if they answered “yes” in 1986 but “no” in 2004 (n= 141), or persistent smokers if they answered “yes” in both 1986 and 2004 (n=59). Eight women reported no smoking in 1986 but smoking in 2004; however, due to the small sample size, these women were excluded from this study. Thus, 1,920 women were eligible respondents for the present study. Data on the usual number of cigarettes smoked was not available.

QOL

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 Version 2 (SF-36) was included in the 2004 follow-up questionnaire to measure QOL of the IWHS cohort.12, 13 SF-36 is a reliable and valid instrument for global assessment of quality of life. It measures QOL in the past four weeks on eight scales: General Health, Physical Functioning, Role Physical, Bodily Pain, Vitality, Mental Health, Role Emotional, and Social Functioning. Each individual scale was standardized to age-specific 1998 population norms by using z-score standardization and norm-based transformation of each scale’s z-score using established algorithms.14 A mean of 50 represents the population average for a given scale, with each point below or above the mean indicating 1/10th of a standard deviation. Higher scores indicate better QOL in all scales.

Cancer diagnosis and treatment

Primary cancer type, diagnosis date, histology, stage, and first course of treatment were obtained from SEER. Cancer stage was classified into four categories: in situ, local, regional, distant. The proportion of women receiving surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy was also calculated.

Demographics, health, and lifestyle characteristics

Potential confounding factors in the relationship between smoking status and QOL were obtained from the baseline questionnaire in 1986 and/or the 2004 questionnaire. Age and education were collected at baseline. Participants were also compared for how they rated their overall health at baseline. Participants reported their current height and weight at baseline and in 2004. Body mass index for each time point was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height (meters) squared; categories were defined as normal (< 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2).15 Physical activity level was also obtained at baseline and at follow-up in 2004. Women were assigned a “high” physical activity level score if they participated in vigorous activity (such as jogging, racquet sports, swimming, aerobics, strenuous sports) two or more times per week or participated in moderate activity (such as bowling, golf, light sports or physical exercise, gardening, taking long walks) more than four times per week. Women were assigned a “medium” physical activity level score if they participated in vigorous activity once a week or participated in moderate activity one to four times per week. All remaining women were assigned a “low” physical activity level score. At baseline and at each follow-up, women reported medical history, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, fracture, stroke, heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or Parkinson’s disease. Women were classified as having one of these conditions based upon on the first report of the health condition at any data collection point. The cumulative number of comorbid conditions reported on all questionnaires was calculated for each participant.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

To examine non-response bias, eligible respondents, deceased participants, and non-respondents were compared for demographics, lifestyle characteristics, comorbid conditions, and cancer-related characteristics. To identify potential confounders, similar comparisons were performed among eligible respondents according to smoking status – that is, non-smokers, former smokers, and persistent smokers.

Two approaches were employed to examine the association between smoking status and QOL. First, age-adjusted mean scores for each SF-36 scale across smoking groups were calculated using generalized linear regression. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance of differences across the age-adjusted mean scores. This approach has been used in most QOL studies using SF-36. However, the difference in mean scores across smoking groups may not provide clinically meaningful information. Therefore we used the second approach reporting the percent of individuals with poor QOL which was defined as scores that fell more than one-half a standard deviation below the mean of the non-smokers since clinicians are mostly interested in identifying patients with poor QOL. One-half a standard deviation is chosen based on systematic review by Norman who concluded that ½ SD appears to be clinically meaningful difference in QOL assessment. 16 Then the odds ratio was calculated for poor QOL in each SF-36 scale among former smokers and persistent smokers compared to non-smokers. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for this analysis were obtained using logistic regression.

Potential confounders, including baseline general health perception, education, cancer type, cancer stage, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, length of survival, the number of comorbid conditions, BMI, and physical activity, were individually examined for whether they meaningfully changed the age-adjusted mean scores of any SF-36 scale. Only BMI and physical activity, as measured in 2004, changed the score more than 5% in absolute value in any scale. Multivariate-adjusted odds ratios were calculated adjusted for age at baseline, stage of cancer, number of comorbid conditions and BMI (2004). Because of changes to the odds ratios when physical activity (2004) was added to the multivariate model, results are presented separately from those adjusted for age, stage, comorbidity and BMI. Finally, a linear trend test of odds ratios across smoking status was performed.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Descriptive characteristics of deceased participants, non-respondents, and eligible respondents are listed in Table 1. At baseline, eligible respondents were generally younger, more educated, less obese, never smokers, and healthier as measured by general health perception and incidence of chronic disease and fractures as compared to deceased participants or non-respondents. In addition, eligible respondents were more physically active at baseline compared to deceased participants, as well as being more likely to have had their cancer diagnosed at an earlier stage (in situ or local). Deceased participants were more frequently diagnosed with colorectal cancer and less frequently diagnosed with breast cancer compared to eligible respondents or non-respondents. Non-respondents and eligible respondents did not differ significantly in terms of the type of cancer, stage at diagnosis, or therapy received.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of women diagnosed with breast, colorectal or endometrial cancer in the Iowa Women’s Health Study according to response to the 2004 follow-up questionnaire

| Deceased Participants (n=1,389) | At 2004 follow-up

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-respondents1 (n=1,019) | Eligible Respondents (n=1,920) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Baseline characteristics, 1986 | ||||||

| Age ≥ 65 years | 595 | 42.8 | 334 | 32.8 | 410 | 21.4 |

| Post secondary education | 519 | 37.5 | 376 | 37.0 | 851 | 44.4 |

| General health, excellent | 253 | 18.5 | 237 | 23.6 | 566 | 29.8 |

| Body mass index ≥30kg/m2 | 458 | 33.0 | 286 | 28.1 | 494 | 25.7 |

| Cigarette smoking, never | 863 | 63.2 | 648 | 65.9 | 1333 | 69.4 |

| Physical activity, low | 719 | 52.8 | 450 | 45.6 | 888 | 46.8 |

| Diabetes | 162 | 11.7 | 48 | 4.7 | 73 | 3.8 |

| Hypertension | 606 | 43.6 | 405 | 39.7 | 679 | 35.4 |

| Heart disease | 63 | 4.5 | 22 | 2.2 | 34 | 1.8 |

| Heart attack | 151 | 10.9 | 75 | 7.4 | 122 | 6.4 |

| Fracture | 189 | 13.6 | 142 | 13.9 | 234 | 12.2 |

| Comorbidity index2 ≥ 2 | 272 | 19.6 | 134 | 13.2 | 212 | 11.0 |

| Cancer characteristics, 1986–2004 | ||||||

| Type of Cancer | ||||||

| Breast | 669 | 48.2 | 651 | 63.9 | 1216 | 63.3 |

| Colorectal | 544 | 39.2 | 248 | 24.3 | 464 | 24.2 |

| Endometrial | 176 | 12.7 | 120 | 11.8 | 240 | 12.5 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||||

| In situ | 64 | 4.7 | 102 | 10.1 | 234 | 12.3 |

| Local | 550 | 40.5 | 663 | 65.9 | 1250 | 65.7 |

| Regional | 463 | 34.1 | 230 | 22.9 | 403 | 21.2 |

| Distant | 280 | 20.6 | 11 | 1.1 | 16 | 0.8 |

| Cancer Therapy Received | ||||||

| Surgery | 1272 | 91.6 | 995 | 97.6 | 1907 | 99.3 |

| Chemotherapy | 335 | 24.1 | 168 | 16.5 | 347 | 18.1 |

| Radiation therapy | 281 | 20.2 | 246 | 24.1 | 448 | 23.3 |

Twenty nine ineligible respondents were excluded because smoking data was not available (n=21) or the women did not smoke in 1986 but did in 2004 (n=8).

Comorbidity index is the sum of self-reported illness including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, heart attack, and fracture.

Non-smokers were slightly older than former or persistent smokers. (Table 2) The percentage of obese non-smokers was higher than former or persistent smokers at baseline. Although this percentage remained relatively unchanged from baseline to 2004, the percentage of obese former smokers increased and surpassed that of non-smokers by 2004. In contrast, the number of obese persistent smokers decreased by 2004. Low physical activity was common among all groups, especially persistent smokers, both at baseline and in 2004. Although non-smokers and former smokers were more likely than persistent smokers to have diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and/or fracture, these differences were not statistically significant. However, the difference in stroke among the groups was statistically significant (p<0.05), with stroke being more common among persistent smokers than former or non-smokers. Breast cancer was the most common diagnosis in both smoking groups followed by colorectal and endometrial cancer. Persistent smokers were more likely to have localized cancer compared to former smokers. Most participants received surgical treatment for their cancers; however, the proportion was lowest among persistent smokers. No difference was found in education level, general health perception at baseline, or survival since cancer diagnosis among the three groups.

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of women with breast, colorectal or endometrial cancer by smoking status, Iowa Women’s Health Study

| Characteristics | % of Women

|

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smokers (n=1,720) | Former smokers (n=141) | Persistent smokers (n=59) | ||

| Age at baseline, years | <0.05† | |||

| Mean | 61.2 | 59.9 | 59.7 | |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | |

| Post secondary education, % | 44.8 | 41.1 | 39.0 | 0.82 |

| General health in 1986, % Excellent | 29.6 | 35.0 | 23.7 | 0.27 |

| BMI ≥ 30kg/m2, % | ||||

| Baseline, | 26.9 | 12.2 | 15.6 | <0.05 |

| 2004 | 26.4 | 29.0 | 7.0 | <0.05 |

| % Low physical activity | ||||

| Baseline | 45.0 | 59.3 | 67.8 | <0.05 |

| 2004 | 50.5 | 64.3 | 71.9 | <0.05 |

| 3+ comorbid conditions, % | 32.5 | 32.6 | 27.2 | 0.72 |

| Type of comorbidity,% | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 17.3 | 15.6 | 8.5 | 0.19 |

| Hypertension | 66.0 | 56.0 | 69.5 | 0.05 |

| Heart disease | 27.2 | 33.3 | 20.3 | 0.13 |

| Stroke | 6.6 | 9.2 | 15.3 | <0.05 |

| Fracture | 39.1 | 38.3 | 28.8 | 0.64 |

| Cancer type, % | 0.40 | |||

| Breast | 63.1 | 66.0 | 64.4 | |

| Colorectal | 24.4 | 24.1 | 16.9 | |

| Endometrial | 12.5 | 9.9 | 18.7 | |

| Years since cancer diagnosis | NS | |||

| Mean | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.3 | |

| SE | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | |

| Cancer stage, % | <0.05 | |||

| In situ | 12.8 | 8.6 | 5.3 | |

| Local | 65.1 | 67.3 | 79.0 | |

| Regional/Distant | 22.0 | 23.7 | 15.8 | |

| Cancer treatment, % | ||||

| Surgery | 99.5 | 97.9 | 96.6 | <0.05 |

| Radiation treatment | 23.5 | 23.4 | 18.6 | 0.69 |

| Chemotherapy | 18.4 | 17.0 | 11.9 | 0.42 |

SE=standard error; NS=not significant

between non-smokers and former smokers as well as non-smokers and persistent smokers

QOL

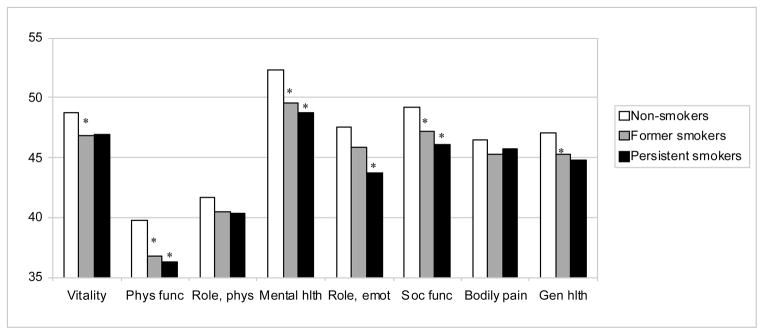

The QOL of non-smokers was comparable to or slightly higher than that of former and persistent smokers as assessed by age-adjusted mean scores for each SF-36 QOL scale (Figure 1). Non-smokers had higher mean scores than former smokers for the Vitality, Physical Functioning, Mental Health, Social Functioning, and General Health scales, while they had higher mean scores than persistent smokers for the Physical Functioning, Mental Health, Role Emotional, and Social Functioning scales. Mean scores did not differ statistically between former and persistent smokers on any SF-36 scale.

Figure 1. Age-adjusted SF-36 scores according to smoking status.

* p<0.05 compared to non-smokers

Abbreviations: SF-36, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36; Phys, Physical; func, functioning; Hlth, Health; Emot, Emotional; Soc, Social; Gen, General

Non-smokers were least likely to have poor QOL followed by former smokers and persistent smokers for six of the eight SF-36 scales (Table 3). Only General Health and Role Physical did not correspond to this pattern by smoking status. Compared to non-smokers, persistent smokers were at increased risk of poor QOL in Physical Functioning, Mental Health, and Role Emotional whereas former smokers were at increased risk in Physical Functioning, Mental Health, and General Health. A statistically significant trend toward higher likelihood of poor QOL was observed across smoking groups in Vitality, Physical Functioning, Mental Health, and Role Emotional. Further adjustment for physical activity resulted in considerable attenuation of the odds ratios and p-values for trend.

Table 3.

Odds ratios of poor QOL* according to smoking status among women with breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancer, Iowa Women’s Health Study

| SF-36 scales | Non-smokers (n=1,720)

|

Former smokers (n=141)

|

Persistent smokers (n=59)

|

P-value3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %1 | Ref | %1 | OR2 | 95% CI | %1 | OR2 | 95% CI | ||

| Vitality | 27.3 | 1.0 | 31.9 | 1.32 | 0.89–1.96 | 33.9 | 1.72 | 0.94–3.15 | 0.03 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.14 | 0.76–1.71 | 1.21 | 0.64–2.28 | 0.42 | |||

| Physical Functioning | 29.6 | 1.0 | 35.5 | 1.65 | 1.10–2.45 | 39.0 | 2.40 | 1.32–4.37 | 0.0003 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.38 | 0.91–2.09 | 1.45 | 0.76–2.75 | 0.08 | |||

| Role Physical | 47.4 | 1.0 | 49.7 | 1.29 | 0.89–1.86 | 45.8 | 1.21 | 0.68–2.15 | 0.20 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.12 | 0.77–1.65 | 0.82 | 0.45–1.50 | 0.89 | |||

| Mental Health | 24.8 | 1.0 | 34.0 | 1.62 | 1.11–2.37 | 40.7 | 1.92 | 1.09–3.40 | 0.002 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.47 | 1.00–2.16 | 1.36 | 0.74–2.47 | 0.06 | |||

| Role Emotional | 24.2 | 1.0 | 27.7 | 1.34 | 0.89–2.01 | 35.6 | 2.01 | 1.10–3.66 | 0.01 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.19 | 0.78–1.80 | 1.35 | 0.72–2.55 | 0.24 | |||

| Social Functioning | 26.1 | 1.0 | 29.1 | 1.27 | 0.85–1.89 | 33.9 | 1.62 | 0.89–2.95 | 0.06 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.11 | 0.73–1.67 | 1.05 | 0.55–1.99 | 0.69 | |||

| Bodily Pain | 30.4 | 1.0 | 33.3 | 1.21 | 0.82–1.79 | 37.3 | 1.60 | 0.89–2.87 | 0.07 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.06 | 0.71–1.58 | 1.16 | 0.63–2.14 | 0.59 | |||

| General Health | 29.7 | 1.0 | 39.0 | 1.51 | 1.03–2.21 | 33.9 | 1.13 | 0.62–2.09 | 0.12 |

| PA adjusted | 1.0 | 1.32 | 0.89–1.95 | 0.76 | 0.40–1.45 | 0.88 | |||

PA=physical activity; OR=odds ratio; CI= confidence interval

Poor QOL defined as women with QOL scores ½ SD below the mean for women in the non-smoking group.

proportion of women who had poor QOL

All odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values for trend adjusted for age, stage of cancer, number of comorbid conditions and BMI (2004); estimates also adjusted for physical activity (2004) as indicated.

p-values for trend comparing former and persistent smokers to non-smokers

DISCUSSION

Among postmenopausal women who developed non-smoking related cancers of breast, colorectal and endometrial origin while participating in a prospective cohort since 1986 the present study found that persistent or former smokers were more likely to have poor QOL after cancer diagnosis. These results are consistent with studies in the general population7–10 and studies in survivors of smoking-related cancers.3–6 In the general population, current smokers were twice as likely to report poor physical and mental health compared to non-smokers 9, and former smokers scored lower than non-smokers in Physical Functioning and General Health. 10 In a study of head and neck cancer survivors, persistent smokers had poorer role function and cognitive function compared to never smokers, while former smokers scored between never smokers and current smokers. 5

The beneficial effect of smoking cessation on QOL has been shown in the general population 8 as well as in head and neck cancer patients.4 Although comparisons between smoking groups did not always yield statistically significant differences in QOL in the present study, a significant trend toward worse QOL was observed for former and persistent smokers compared to non-smokers. That former smokers had somewhat better QOL than persistent smokers suggests that smoking cessation could improve QOL among survivors of non-smoking related cancers. The lack of a statistically significant difference in QOL scores between former and persistent smokers could be due to the relatively small number of subjects. Another explanation is that former smokers may have quit smoking after development of an illness, such as heart attack or stroke, which in turn lowered their QOL scores, thereby leading to an underestimation of the difference in QOL between former and persistent smokers.

The likelihood of poor QOL in former and persistent smokers relative to non-smokers may have been underestimated for two reasons. First, eligible respondents were more likely to be never smokers than deceased participants or non-respondents to the 2004 questionnaire. Because these latter two groups were excluded from the analysis, survivorship bias could have affected the results if, as seems highly possible, eligible respondents who smoked and survived to complete the 2004 questionnaire were healthier and as a consequence reported better QOL than women excluded from the analysis. This conclusion is supported by the lower proportion of women with more than three comorbid conditions among persistent smokers compared to non-smokers. Second, approximately 23% of women classified as non-smokers at baseline had smoked prior to study entry. These women may have quit smoking due to health conditions that could contribute to poorer QOL. In addition, women were classified as former smokers without regard to the time they last smoked. Although smoking status was assessed at each follow-up, this information represents only an approximation of the length of smoking cessation because the questionnaires were administered infrequently, at irregular intervals, and did not record the date last smoked.

Physical activity is usually not taken into account in studies evaluating the impact of smoking on QOL. In this study, adjustment for physical activity greatly attenuated the difference in QOL among smoking groups relative to non-smokers. This finding suggests that low physical activity among persistent and former smokers was one of the main reasons for poor QOL. A recent systematic review on smoking and physical activity showed that 60% of studies reported physical activity to be less likely among smokers relative to non-smokers.17 The most common explanation for this inverse relationship is that positive or negative behaviors tend to cluster together, thus, smokers were more likely to engage in risky behaviors.18 This clustering has also been observed among cancer survivors.19 Another possibility is that the ability to engage in physical activity may be impaired by reduced physical capacities in smokers, especially with respect to pulmonary function.20 An alternative explanation can be found in what is known about the relationship between physical activity, depression and smoking. Physical activity and depression have been inversely associated in some studies, potentially because physical activity increases the release of norepinephrine, which in turn is associated with decreased rates of depression.21–22 In contrast, smoking and depression are often found to be positively related.23 Therefore, it is possible that lower levels of physical activity may lead to increased levels of depression and, consequently, smoking.24 However, since previous studies show a positive association between physical activity and QOL among cancer survivors19 and even in elderly populations,25 it seems more plausible that physical activity is in the causal pathway leading to poor QOL among smokers.

Our study has several limitations. Despite the opportunity to prospectively identify cancer cases and smoking status, we collected QOL data at only one point in time. Although QOL can change during the course of cancer survivorship,26 the mean time since diagnosis was similar across smoking groups, suggesting that QOL was not affected by variation in the acute or long-term effects of a cancer diagnosis in the study population. Second, QOL and lifestyle factors were collected with the self-administered questionnaires which may subject to positivity bias. Another limitation of the study is that the amount of smoking was not assessed. Thus, the possibility that persistent smokers were among the lightest or heaviest smokers in the cohort cannot be excluded. The former is more likely as evidenced by the lower prevalence of comorbid conditions among persistent smokers. However, important comorbidity data was also missing, especially data on the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, and depression. Thus, some differences in QOL by smoking status could be due to the presence of unaccounted comorbid conditions. Finally, the reason for and timing of smoking cessation was not available.

In conclusion, this study found that postmenopausal women with non-smoking related cancers reported poorer QOL if they were persistent or former smokers than if they had never smoked during the observation period. Indeed, the trend toward worse QOL with increasing level of active smoking suggests that continued smoking after cancer diagnosis may lead to poorer QOL in survivors of non-smoking related cancers. Also we found that physical activity may be the mechanism by which smoking leads to poorer QOL among smokers. Knowing this, oncologists may consider a cancer diagnosis to be a teachable moment for promoting health behavior change.27–29

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Aaron Folsom, Principal Investigator of the Iowa Women’s Health Study, and Michael J. Franklin, MS of the University of Minnesota for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in 2009 and received Merit Award.

Financial disclosures: This research was supported by a National Cancer Institute award, R01 CA39742.

References

- 1.Giovino GA. The tobacco epidemic in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:S318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. Smoking cessation and continued risk in cancer patients (PDQ) Available from URL: http://www.nci.nih.gov/cancerinfo/pdq/supportivecare/smokingcessation/healthprofessional.

- 3.Duffy SA, Terrell JE, Valenstein M, Ronis DL, Copeland LA, Connors M. Effect of smoking, alcohol, and depression on the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:140–147. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gritz ER, Carmack CL, de Moor C, Coscarelli A, Schacherer CW, Meyers EG, et al. First year after head and neck cancer: quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:352–360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen K, Jensen AB, Grau C. Smoking has negative impact upon health related quality of life after treatment for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncology. 2007;43:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garces Y, Yang P, Parkinson J, Zhao X, Wampfler JA, Ebbert JO, et al. The relationship between cigarette smoking and quality of life after lung cancer diagnosis. Chest. 2004;126:1733–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strandberg AY, Strandberg TE, Pitkälä K, Salomaa VV, Tilvis RS, Miettinen TA. The effect of smoking in midlife on health-related quality of life in old age. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1968–1974. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tillman M, Silcock J. A comparison of smokers’ and ex-smokers’ health-related quality of life. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1997;19:268–273. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mody R, Smith M. Smoking status and health-related quality of life: findings from the 2001 behavioral risk factor surveillance system data. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2006;20:251–258. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.4.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson D, Parsons J, Wakefiled M. The health-related quality-of-life of never smokers, ex-smokers, and light, moderate, and heavy smokers. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29:139–144. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folsom AR, Kaye SA, Seller TA, Hong CP, Cerhan JR, Potter JD, et al. Body fat distribution and 5-year risk of death in older women. JAMA. 1993;269:483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushi LH, Kaye SA, Folsom AR, Soler JT, Prineas RJ. Accuracy and reliability of self-measurement of body girths. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:740–748. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life- the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care. 2003;41:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaczynski AT, Manske SR, Mannell RC, Grewal K. Smoking and Physical activity: A systematic review. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:93–110. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strine TW, Okoro CA, Chapman DP, Balluz LS, Ford ES, Ajani UA, et al. Health-related quality of life and health risk behaviors among smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivor’s adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with Health-related Quality of Life: Results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold DR, Wang X, Wypij D, Speizer FE, Ware JH, Dockery DW. Effects of cigarette smoking on lung function in adolescent boys and girls. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:931–937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norrs R, Carroll D, Cochrane R. The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90114-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cronan TL, Howley ET. The effect of training on epinephrine and norepinephrine execretion. Med Sci Sports. 1974;6:122–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Comorbidity between depressive disorders and nicotine dependence in a cohort of 16 year olds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1043–1047. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Moss HB. Smoking progression and physical activity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:1121–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White SM, Wójcicki TR, McAuley E. Physical activity and quality of life in community dwelling older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate cancer survivors. N Eng J Med. 2008;358:125–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz N, Rowland J, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: Promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–5830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: Smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:17–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McBride CM, Ostroff JS. Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: The context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control. 2003;10:325–333. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]