Abstract

Using lysophosphatidylcholine, a curvature-inducing lysolipid, we have isolated a reversible, “stalled pore” phenotype during syncytium formation induced by the p14 fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) protein and influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) fusogens. This is the first evidence that lateral propagation of stable fusion pores leading to syncytiogenesis mediated by diverse viral fusogens is inhibited by promotion of positive membrane curvature in the outer leaflets of the lipid bilayer surrounding intercellular fusion pores.

TEXT

Enveloped viruses rely on fusion proteins to mediate virus-cell membrane fusion during cell entry (1). These same fusion proteins, when present in the plasma membrane of virus-infected cells, can induce cell-cell membrane fusion and syncytium formation. Studies of viral fusogens have been instrumental in development of the fusion-through-hemifusion paradigm of protein-mediated membrane fusion (2, 3). Initial formation of a hemifusion stalk structure from merger of outer bilayer leaflets progresses to pore formation. These transitions are driven by energy released during dramatic fusion protein conformational changes involving an extended intermediate that converts to a folded-back, trimeric hairpin structure (4). In a poorly understood process, subsequent expansion of these micropores generates the macropores needed for syncytium formation.

The fusogenic orthoreoviruses and aquareoviruses are the only examples of nonenveloped viruses that induce syncytium formation, and syncytium formation is a virulence determinant of these viruses (5, 6). Each of these viruses encodes a fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) protein that evolved specifically to induce cell-cell, rather than virus-cell, membrane fusion (7). As dedicated cell-cell fusogens, the FAST proteins differ from enveloped virus fusogens both in their primary biological function and structural features. The FAST proteins are the smallest membrane fusion proteins and, with vestigial ectodomains of only ∼20 to 40 residues (8–13), are unlikely to mediate membrane fusion using the pathway envisioned for enveloped virus fusogens.

FAST protein-induced syncytium formation does not respond to compounds that alter membrane curvature in a manner analogous to enveloped virus fusogens, consistent with the concept that these different classes of viral fusogens differ in their mechanism of action. Lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is a lysolipid with a large polar head group and a single hydrocarbon chain. When inserted into the outer leaflet of a lipid bilayer, this inverted cone shape promotes positive curvature (i.e., the monolayer bulges out toward the polar headgroups), the opposite curvature needed to form a hemifusion stalk (14). LPC effectively inhibits hemifusion induced by numerous enveloped virus fusogens (15–19) but has no effect on pore formation caused by the reptilian reovirus (RRV) p14 FAST protein (20). Here, we report a novel, LPC-sensitive stage during virus-mediated cell-to-cell fusion that follows the formation of stable fusion pores.

In our previous study, cell-cell fusion was assessed using a dual fluorescence pore formation assay (20). In this assay, sparsely seeded donor QM5 cells cotransfected with RRV p14 and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression vectors are overseeded at 4 h posttransfection (hpt), just prior to the onset of syncytium formation, with target Vero cells labeled with 10 μM CellTrace calcein red-orange AM. Cells are cocultured for an additional 4 h and then resuspended, fixed, and analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of EGFP donor cells that acquired calcein red, indicative of pore formation. As previously reported (20), cells cocultured in the presence of 100 μM myristoyl LPC (added 1 h after the addition of target cells) induced the same extent of pore formation as untreated cells (Fig. 1A). The addition of LPC concurrent with the addition of target cells (LPC at 0 min in Fig. 1A) inhibited or delayed pore formation by ∼30%. While this might reflect a modest direct inhibitory effect of LPC on p14-induced pore formation, we noted by microscopy that target cells were slow to firmly attach to donor cells under these conditions. In contrast, LPC inhibits pore formation induced by enveloped virus fusogens by >80% (20). Thus, unlike other viral fusogens, p14-induced hemifusion and pore formation are relatively LPC insensitive.

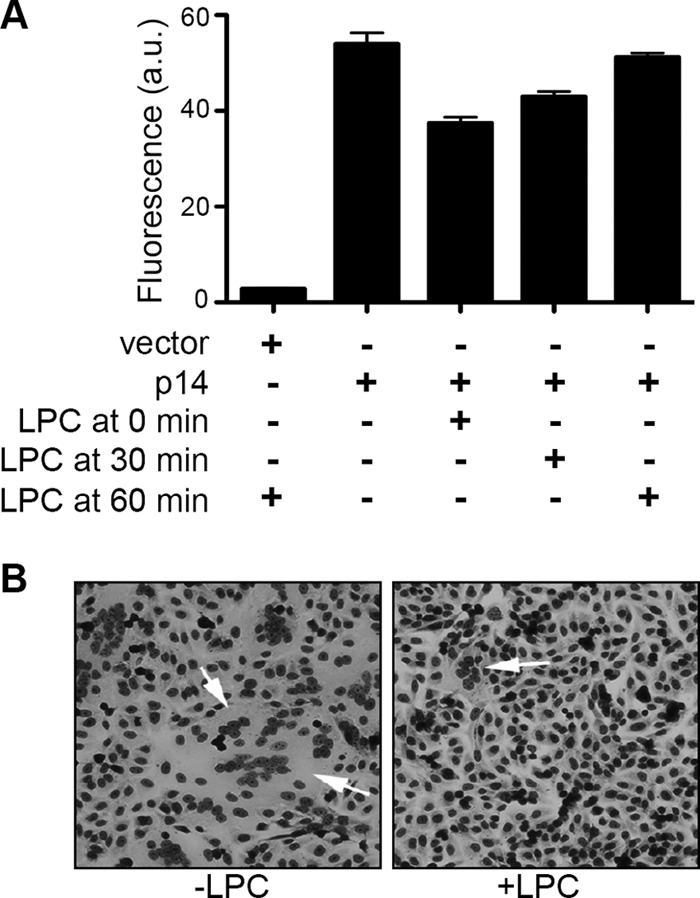

FIG 1.

Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits p14-mediated syncytium formation but not pore formation. (A) At 4 hpt, QM5 cells cotransfected with p14 and EGFP were overseeded with Vero cells labeled with CellTrace calcein red-orange AM. Myristoyl LPC (100 μM) was added to culture medium concurrent with the addition of Vero cells (0 min) or 30 or 60 min after Vero cell addition. Cells were cocultured for 4 h, and the percentage of EGFP-positive cells that acquired calcein red was quantified by flow cytometry. Results are means ± SD from a representative experiment in triplicate (n = 2). (B) QM5 cell monolayers transfected with p14 were left untreated (−LPC) or treated with 100 μM myristoyl LPC (+LPC) at 4 hpt and then fixed and Giemsa stain at 8 hpt to visualize syncytium formation (arrows) by bright-field microscopy.

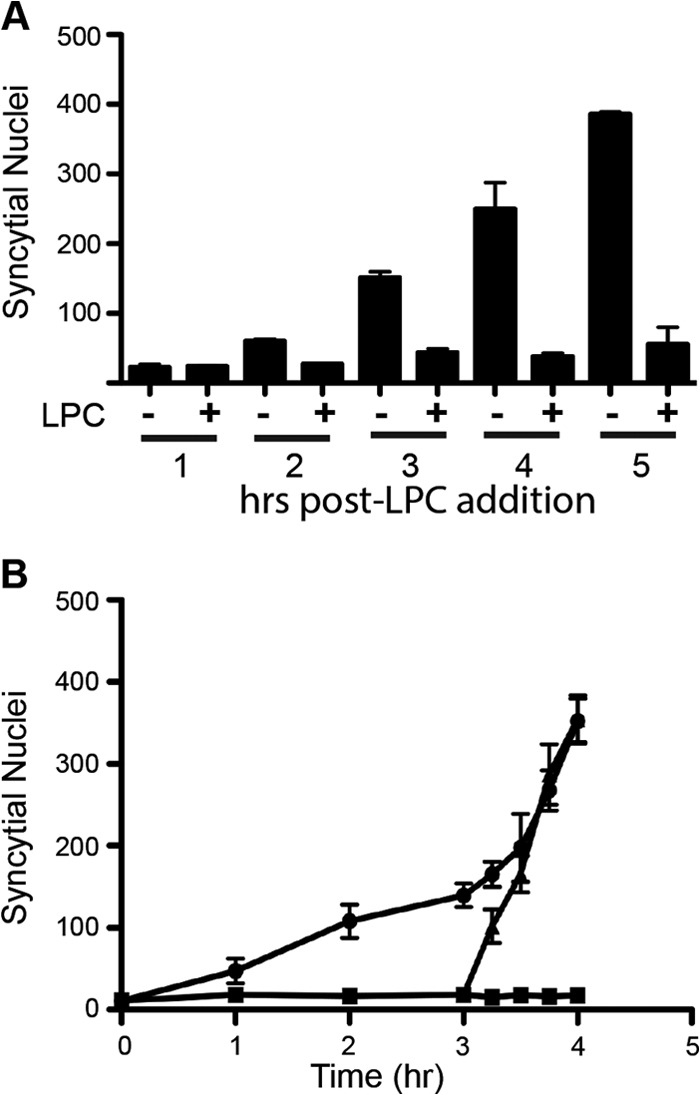

Interestingly, when cells were fixed, Giemsa stained, and examined by light microscopy at the end of the pore formation assay, we noted that LPC almost completely inhibited p14-induced syncytium formation (Fig. 1B). These results were repeated in p14-transfected QM5 cell monolayers, and syncytium formation was quantified by determining the average number of syncytial nuclei present in five random microscopic fields of Giemsa-stained monolayers at various times posttransfection. As shown in Fig. 2A, the addition of LPC at 4 hpt essentially abrogated syncytium formation; LPC therefore dramatically inhibits p14-induced syncytiogenesis but not membrane fusion and pore formation, implying that the expansion of stable micropores into macropores is LPC sensitive. As with LPC-inhibited hemifusion induced by enveloped virus fusogens (21), the block in p14-induced pore expansion was completely reversible (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, syncytiogenesis progressed at a markedly increased rate after removal of LPC, reaching a level of syncytium formation equivalent to that of untreated cells within 30 to 45 min after LPC removal (Fig. 2B). The increased rate of syncytiogenesis following release of the LPC-mediated block to pore expansion suggests that fusion pores continue to form in the presence of LPC and are poised for expansion upon relief of the membrane curvature constraints imposed by the lysolipid.

FIG 2.

Lysophosphatidylcholine arrest of p14-mediated syncytium formation is reversible. (A) QM5 cell monolayers transfected with p14 and cultured with or without LPC as described for Fig. 1B were fixed and Giemsa stained at the indicated times after LPC addition, and the average number of syncytial nuclei per microscopic field was quantified. Results are means ± SD from a representative experiment in triplicate (n = 2). (B) QM5 cells transfected with p14 (circles), treated with 100 μM myristoyl LPC at 4 hpt (squares) or treated with LPC, which was then removed from culture medium after 3 h of incubation (triangles), were fixed and Giemsa stained at the indicated times after LPC addition, and syncytium formation was quantified as described for panel A. Results are means ± SD from a representative experiment in triplicate (n = 2).

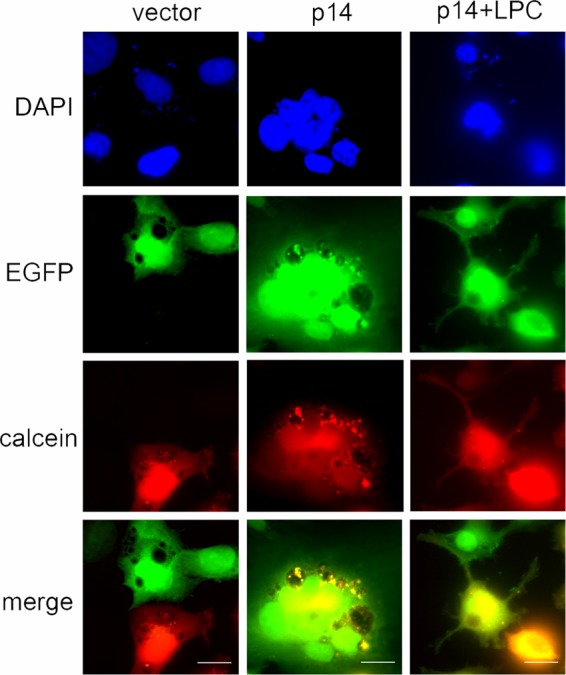

Using fluorescence microscopy to visualize content mixing in the absence of syncytium formation, we confirmed that LPC can “trap” fusion pores by inhibiting their expansion. At 4 hpt, donor HT1080 cells cotransfected with RRV p14 and EGFP expression vectors were overseeded with HT1080 target cells labeled with CellTrace calcein red-orange AM, 100 μM myristoyl LPC was added 1 h after coculture, and cells were fixed at 12 hpt and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. No dye transfer was observed in vector-transfected cells, while dual fluorescent syncytia were apparent in p14-transfected cell monolayers in the absence of LPC (Fig. 3). As predicted, numerous mononucleated, dual fluorescent cell pairs were observed in p14-transfected cell monolayers treated with LPC, but multinucleated syncytia were absent. These cell pairs contained obvious intercellular connections, either between closely apposed cells or extending considerable distances between cells (Fig. 3). LPC therefore does not inhibit p14-induced cell-cell hemifusion or pore formation, but it does prevent pore expansion needed for syncytium formation.

FIG 3.

Lysophosphatidylcholine induces a stalled pore phenotype during p14-mediated syncytium formation. At 4 hpt, donor HT1080 cells cotransfected with p14 and EGFP were cocultured with target HT1080 cells labeled with calcein red-orange for 8 h, fixed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and imaged on a Zeiss Axioplan II MOT fluorescence microscope with a 63× objective. The EGFP and calcein red channels are shown together in the merge. Scale bar = 10 μm.

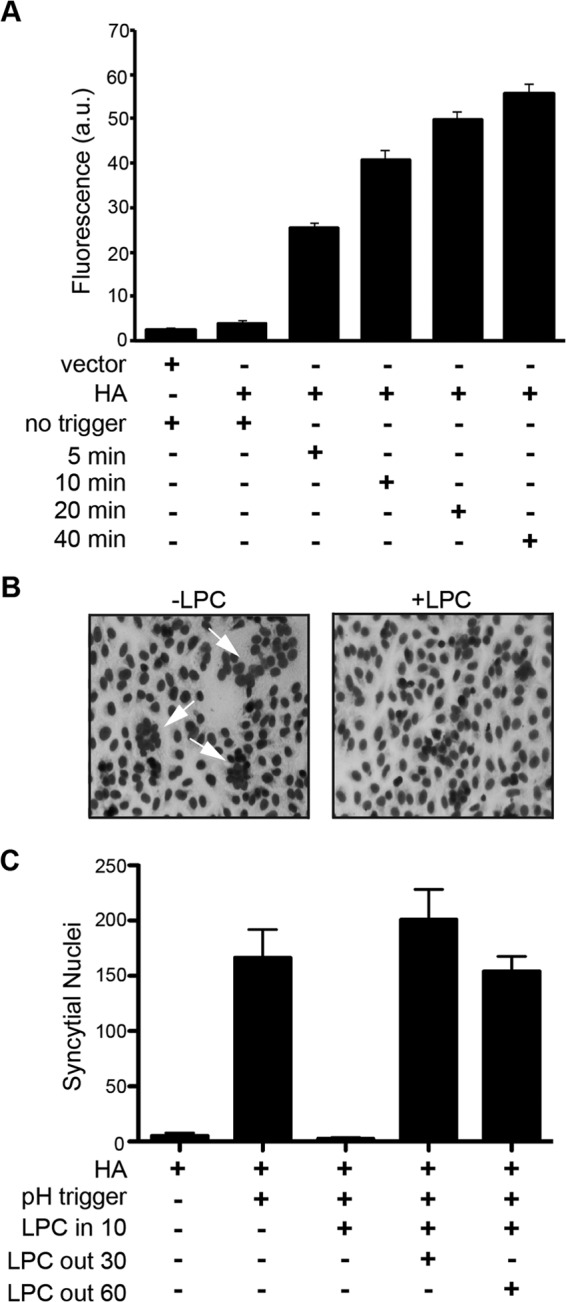

To determine whether LPC can also arrest expansion of pores generated by enveloped virus fusogens, influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA)-mediated pore expansion and syncytium formation was analyzed to define a post-pore formation, pre-syncytium formation interval for LPC addition. At 24 hpt, donor QM5 cells transfected with HA and EGFP expression vectors were overseeded with target Vero cells labeled with calcein red. The donor and target cells were cocultured for 4 h and subsequently treated with 10 μg/ml of trypsin for 3 min to effect cleavage activation of HA0 to HA1 and HA2. Cells were then treated for 1 min with tissue culture medium buffered to pH 4.8 to trigger conformational changes of the HA fusion complex necessary for mediating membrane merger and pore formation. Flow cytometry analysis of soluble dye transfer between donor and target cells revealed HA-mediated pore formation was detectable <5 min after triggering fusion (Fig. 4A), while syncytium formation was not evident until ∼15 min after pH treatment (data not shown). LPC was therefore added 10 min after the pH trigger, when pore formation was substantial (Fig. 4A) but no visible syncytia were present (Fig. 4C). The addition of LPC at this time inhibited HA-mediated syncytium formation, as observed in Giemsa-stained monolayers (Fig. 4B) and by quantifying syncytial nuclei 2 h after pH trigger (Fig. 4C). As with p14, LPC inhibition of HA-mediated syncytium formation was fully reversible, with syncytium formation rapidly returning after removal of LPC to levels observed in untreated cell levels (Fig. 4C). LPC is therefore a potent inhibitor of pore expansion and syncytium formation induced by diverse viral fusogens.

FIG 4.

Influenza virus HA-induced syncytiogenesis is sensitive to lysophosphatidylcholine-mediated pore expansion arrest. (A) QM5 cells cotransfected with HA and EGFP plasmid DNA were overseeded with Vero cells labeled with calcein red-orange AM at 24 hpt and cocultured for 4 h. Cells were then treated with trypsin and low pH to activate and trigger HA fusion and were fixed at the indicated times, and the percentage of EGFP-positive cells that acquired calcein red was quantified by flow cytometry. Results are means ± SD from triplicate samples from a representative experiment (n = 2). (B) HA present in transfected QM5 cells was activated and triggered as described for panel A, LPC was added 10 min after triggering, and cells were fixed and Giemsa stained 30 min later and imaged by bright field microscopy. (C) HA-expressing QM5 cells were activated and triggered as described for panel B, LPC was added 10 min after triggering, and cells were cultured for 2 h after triggering in the presence of LPC or following removal of LPC after 30 or 60 min of treatment. Fixed cells were Giemsa stained and syncytial nuclei quantified as described for Fig. 2A. Results are means ± SD from a representative experiment in triplicate (n = 2).

Our results indicate that inhibiting negative membrane curvature in the outer membrane leaflet generates a “stalled pore” phenotype that precedes syncytium formation induced by the p14 FAST protein and influenza virus HA fusogens. Possible membrane curvature effects on pore expansion have recently been described during myoblast fusion into multinucleated myotubes, where protein motifs that generate or associate with the high positive curvature of intracellular membrane compartments may similarly interact with the highly curved inner rim of fusion pores to promote syncytium formation (22, 23). The inhibitory effect of LPC on pore expansion can be explained by induction of positive curvature in the outer leaflet of the membrane bilayer surrounding intercellular fusion pores, which would effectively prevent lateral expansion of negative curvature in the outer rim of a fusion pore. Isolation of a reversible, LPC-sensitive, stalled pore phenotype provides a means to investigate the poorly understood process of micropore conversion into macropores by synchronizing the post-fusion, pore expansion stage of syncytiogenesis. Additionally, while FAST proteins and enveloped virus fusogens may differ in their mechanism of membrane fusion, we now show that the resulting fusion pores can be maintained at a stalled pore stage through the promotion of positive curvature, suggesting pore expansion likely follows a common pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eileen Clancy for the initial observation that LPC inhibits syncytium formation and for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). M.C. was funded by scholarships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (NSHRF).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. 2008. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43:189–219. 10.1080/10409230802058320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. 2008. Mechanics of membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:675–683. 10.1038/nsmb.1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. 2005. Membrane hemifusion: crossing a chasm in two leaps. Cell 123:375–382. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison SC. 2008. Viral membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:690–698. 10.1038/nsmb.1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown CW, Stephenson KB, Hanson S, Kucharczyk M, Duncan R, Bell JC, Lichty BD. 2009. The p14 FAST protein of reptilian reovirus increases vesicular stomatitis virus neuropathogenesis. J. Virol. 83:552–561. 10.1128/JVI.01921-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salsman J, Top D, Boutilier J, Duncan R. 2005. Extensive syncytium formation mediated by the reovirus FAST proteins triggers apoptosis-induced membrane instability. J. Virol. 79:8090–8100. 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8090-8100.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutilier J, Duncan R. 2011. The reovirus fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) proteins: virus-encoded cellular fusogens, p 107–140 In Chernomordik LV, Koslov MM. (ed), Membrane fusion, vol 68 Elsevier, New York, NY: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corcoran JA, Duncan R. 2004. Reptilian reovirus utilizes a small type III protein with an external myristylated amino terminus to mediate cell-cell fusion. J. Virol. 78:4342–4351. 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4342-4351.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawe S, Corcoran JA, Clancy EK, Salsman J, Duncan R. 2005. Unusual topological arrangement of structural motifs in the baboon reovirus fusion-associated small transmembrane protein. J. Virol. 79:6216–6226. 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6216-6226.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Racine T, Hurst T, Barry C, Shou J, Kibenge F, Duncan R. 2009. Aquareovirus effects syncytiogenesis by using a novel member of the FAST protein family translated from a noncanonical translation start site. J. Virol. 83:5951–5955. 10.1128/JVI.00171-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shmulevitz M, Duncan R. 2000. A new class of fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) proteins encoded by the non-enveloped fusogenic reoviruses. EMBO J. 19:902–912. 10.1093/emboj/19.5.902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thalmann CM, Cummins DM, Yu M, Lunt R, Pritchard LI, Hansson E, Crameri S, Hyatt A, Wang LF. 2010. Broome virus, a new fusogenic orthoreovirus species isolated from an Australian fruit bat. Virology 402:26–40. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo H, Sun X, Yan L, Shao L, Fang Q. 2013. The NS16 protein of aquareovirus-C is a fusion-associated small transmembrane (FAST) protein, and its activity can be enhanced by the nonstructural protein NS26. Virus Res. 171:129–137. 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernomordik L, Chanturiya A, Green J, Zimmerberg J. 1995. The hemifusion intermediate and its conversion to complete fusion: regulation by membrane composition. Biophys. J. 69:922–929. 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79966-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chernomordik LV, Leikina E, Frolov V, Bronk P, Zimmerberg J. 1997. An early stage of membrane fusion mediated by the low pH conformation of influenza hemagglutinin depends upon membrane lipids. J. Cell Biol. 136:81–93. 10.1083/jcb.136.1.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melikyan GB, White JM, Cohen FS. 1995. GPI-anchored influenza hemagglutinin induces hemifusion to both red blood cell and planar bilayer membranes. J. Cell Biol. 131:679–691. 10.1083/jcb.131.3.679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaitseva E, Mittal A, Griffin DE, Chernomordik LV. 2005. Class II fusion protein of alphaviruses drives membrane fusion through the same pathway as class I proteins. J. Cell Biol. 169:167–177. 10.1083/jcb.200412059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernomordik L, Leikina E, Cho MS, Zimmerberg J. 1995. Control of baculovirus gp64-induced syncytium formation by membrane lipid composition. J. Virol. 69:3049–3058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuyama S, Delos SE, White JM. 2004. Sequential roles of receptor binding and low pH in forming prehairpin and hairpin conformations of a retroviral envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 78:8201–8209. 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8201-8209.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clancy EK, Barry C, Ciechonska M, Duncan R. 2010. Different activities of the reovirus FAST proteins and influenza hemagglutinin in cell-cell fusion assays and in response to membrane curvature agents. Virology 397:119–129. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leikina E, Chernomordik LV. 2000. Reversible merger of membranes at the early stage of influenza hemagglutinin-mediated fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2359–2371. 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richard JP, Leikina E, Langen R, Henne WM, Popova M, Balla T, McMahon HT, Kozlov MM, Chernomordik LV. 2011. Intracellular curvature-generating proteins in cell-to-cell fusion. Biochem. J. 440:185–193. 10.1042/BJ20111243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leikina E, Melikov K, Sanyal S, Verma SK, Eun B, Gebert C, Pfeifer K, Lizunov VA, Kozlov MM, Chernomordik LV. 2013. Extracellular annexins and dynamin are important for sequential steps in myoblast fusion. J. Cell Biol. 200:109–123. 10.1083/jcb.201207012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]