ABSTRACT

Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) is well known to be upregulated during hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication. The role of PI4 kinases in HCV has been extensively investigated. Whether the PI4P phosphatase Sac1 is altered by HCV remains unclear. Here, we identified ARFGAP1 to be a novel host factor for HCV replication. We further show that Sac1 interacts with ARFGAP1 and inhibits HCV replication. The elevation of PI4P induced by HCV NS5A is abrogated when the coatomer protein I (COPI) pathway is inhibited. We also found an interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1. Furthermore, we identified a conserved cluster of positively charged amino acids in NS5A critical for interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1, induction of PI4P, and HCV replication. Our data demonstrate that ARFGAP1 is a host factor for HCV RNA replication. ARFGAP1 is hijacked by HCV NS5A to remove COPI cargo Sac1 from the site of HCV replication to maintain high levels of PI4P. Our findings provide an additional mechanism by which HCV enhances formation of a PI4P-rich environment.

IMPORTANCE PI4P is enriched in the replication area of HCV; however, whether PI4P phosphatase Sac1 is subverted by HCV is not established. The detailed mechanism of how COPI contributes to viral replication remains unknown, though COPI components were hijacked by HCV. We demonstrate that ARFGAP1 is hijacked by HCV NS5A to remove COPI cargo Sac1 from the HCV replication area to maintain high-level PI4P generated by NS5A. Furthermore, we identify a conserved cluster of positively charged amino acids in NS5A, which are critical for interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1, induction of PI4P, and HCV replication. This study will shed mechanistic insight on how other RNA viruses hijack COPI and Sac1.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of chronic liver disease, including chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, infecting about 170 million people worldwide (1). Treatment of patients with a combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin produces only a sustained virological response in about 50% of patients and often produces serious side effects. Direct translation of the HCV genome gives rise to a polyprotein precursor, which can be further processed by host and viral proteases into structural proteins and nonstructural proteins. Nonstructural proteins NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B are necessary and sufficient for RNA replication (2).

A hallmark of HCV replication is the formation of a membranous web which is induced mainly by NS4B (3). Recent studies have shown that NS5A plays an essential role for maintaining membranous web integrity by activating PI4 kinase type III alpha (PI4KA) to elevate phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) during HCV infection (4–8). Whether the host transport pathway is involved in the PI4P generation by NS5A is unknown.

Sac1 is the key phosphatase that dephosphorylates PI4P (9). Previous work has suggested that Sac1 is a coatomer protein I (COPI) cargo which contains a KXKXX motif (10). Key factors in the COPI pathway, including the coatomer, GBF1, and ARF1, have been identified as host factors for HCV replication (11–14). ARFGAP1 (the GTPase-activating protein for ARF1) plays a central role of cargo sorting in COPI transport (15–17). It is unknown whether ARFGAP1 is involved in HCV replication. Moreover, the mechanism underlying the regulation of HCV infection by COPI has not been conclusively resolved.

In this study, we have found that ARFGAP1 plays a critical role in HCV replication. ARFGAP1 interacts with HCV protein NS5A. Moreover, we reveal a conserved cluster of positively charged amino acids in NS5A critical for its association with ARFGAP1. The elevated level of PI4P induced by NS5A is reduced when the COPI pathway is inhibited. Our findings provide an additional mechanism by which HCV enhances formation of a PI4P-rich environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, virus, and reagents.

Huh 7.5.1 and 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Infectious JFH1 plasmid pJFH1 was obtained from Takaji Wakita (18). Jc1FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) was from Charles Rice. The OR6 cell line, which harbors full-length genotype 1b HCV RNA and coexpresses Renilla luciferase, from Nobuyuki Kato and Masanori Ikeda, was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 μg/ml of G418 (Promega, Madison, WI). QS11, Golgicide A (GCA), and brefeldin A (BFA) were obtained from Sigma Life Science and Biochemicals (St. Louis, MO).

Plasmids.

The constructs Sac1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and Sac1-FLAG were kindly provided by Peter Mayinger (Oregon Health and Science University). The Sac1C/S-GFP mutant was generated using the Stratagene mutagenesis kit by following the protocol with the following pair of primers: 5′-GTTCCGAAGCAATAGCATGGATTGTCTAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTAGACAATCCATGCTATTGCTTCGGAAC-3′ (reverse). Constructs encoding rat ARFGAP1 with glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag or with Myc tag were kindly provided by Victor W. Hsu (Harvard Medical School). Constructs encoding fragments of NS5A from JFH1 fused to GST were constructed into BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX4T-1. The PCR primers to subclone the fragments of NS5A were as follows: NS5A(35–215) forward primer, 5′-CGCGGATCCGCGCCCTTCATCTCTTG-3′; NS5A(35–215) reverse primer, 5′-CCGGAATTCCGGTCACGCCGCAGTCTCCGCCGTGATGT-3′; NS5A(353–444) forward primer, 5′-CGCGGATCGGCCAGACGCCGGACAGTG-3′; NS5A(353–444) reverse primer, 5′-CCGGAATTCCGGTCAGCAGCACACGGTGG-3′; NS5A(35–341) forward primer, 5′-CGCGGATCGGCCCCCTTCATCTCTTG-3′; NS5A(35–341) reverse primer, 5′-CCGGAATTCCGGTCAGGGGGAGAGCACAACCAGCAACG-3′. NS5A-FLAG containing the R/A mutation was generated using the Stratagene mutagenesis kit by following the protocol with the following pair of primers: 5′-CCGACGCCTCCCCCAGCAGCAGCAGCAACAGTGGGTCTGAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTCAGACCCACTGTTGCTGCTGCTGCTGGGGGAGGCGTCGG-3′ (reverse). NS5A-FLAG (containing the R/S mutation), pJFH1R/S (containing the R/S mutation in NS5A), and pJc1FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A)R/S (containing the R/S mutation in NS5A) were generated using the Stratagene mutagenesis kit by following the protocol with the following pair of primers: 5′-CCGACGCCTCCCCCAAGTAGTAGCAGCACAGTGGGTCTGAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTCAGACCCACTGTGCTGCTACTACTTGGGGGAGGCGTCGG-3′ (reverse).

Antibodies.

The primary mouse antibodies included anti-HCV core (Affinity BioReagents Inc., Golden, CO), NS5A (ViroGen, Watertown, MA), NS3 (ViroGen, Watertown, MA), anti-actin (Sigma Life Science and Biochemicals, St. Louis, MO), anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), anti-Myc (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and anti-PI4P (Echelon Biosciences, Salk Lake City, UT). The primary rabbit antibodies included anti-ARFGAP1 antibody (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, Canada), anti-FLAG (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Boston, MA), and anti-Sac1 (generated against the C-terminal tail of Sac1 [NGKDFVDAPRLVQKEKID] conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin [KLH]). Secondary antibodies included horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated ECL donkey anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-conjugated ECL sheep anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), goat anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 594, and goat anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescence observed using Leica TCS SP5 microscopy (Germany) was performed as previously described (11).

Protein interaction assays.

Immunoprecipitation experiments and GST pulldown experiments were performed as previously described (19, 20).

Knocked down by siRNA.

The small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Negative-control siRNA and the siRNAs used for ARFGAP1, ARFGAP2, ARFGAP3, and Sac1 knockdown were from GenePharma (China) and were as follows: ARFGAP1-1, 5′-ACAUUGAGCUUGAGAAGAU-3′; ARFGAP1-2, 5′-ACAGGAGAAGUACAACAGCAGA-3′; ARFGAP2, 5′-GGAGCAGGAAGUGUAUCUCUGTT-3′; ARFGAP3, 5′-CCUAUGGAGUGUUCCUUUGTT-3′; Sac1, 5′-GGCGUGUUCCGAAGCAAUU-3′. The siRNAs used for GBF1 and ARF1 knockdown were from Dharmacon and were as follows: ARF1 Dharmacon D-011580-06 (5′-CGGCCGAGAUCACAGACAA-3′); GBF1 Dharmacon J-019783-06 (5′-CAACACACCUACUAUCUCU-3′).

qPCR.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed as previously described (21). Sequences of primers used in qPCR were as follows: the forward and reverse primers for JFH1 were 5′-TCTGCGGAACCGGTGAGTA-3′ and 5′-TCAGGCAGTACCACAAGGC-3′; the forward and reverse primers for the negative strand of JFH1 were 5′-GGCCGTCATGGTGGCGAATAA-3′ and 5′-CTCCCGGGGCACTCGCAAGC-3′; the forward and reverse primers for the positive strand of JFH1 were 5′-GTCTAGCCATGGCGTTAGTA-3′ and 5′-CTCCCGGGGCACTCGCAAGC-3′; the forward and reverse primers for GAPDH were 5′-ACCTTCCCCATGGTGTCTGA-3′ and 5′-GCTCCTCCTGTTCGACAGTCA-3′; the forward and reverse primers for ARFGAP1 were 5′-GCGCATCCTCATTGCAG-3′ and 5′-CTTCCTGGTTCTTGGGCTG-3′; the forward and reverse primers for Sac1 were 5′-CACATGGACGGTTTCCAAAGGCAT-3′ and 5′-TTCCACTTCCCAAGGAAGACACCA-3′.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses (see Fig. 1 to 7) were performed using a 2-tailed Student t test. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± standard errors of the means (SEM), unless stated otherwise. NS, not significant; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001.

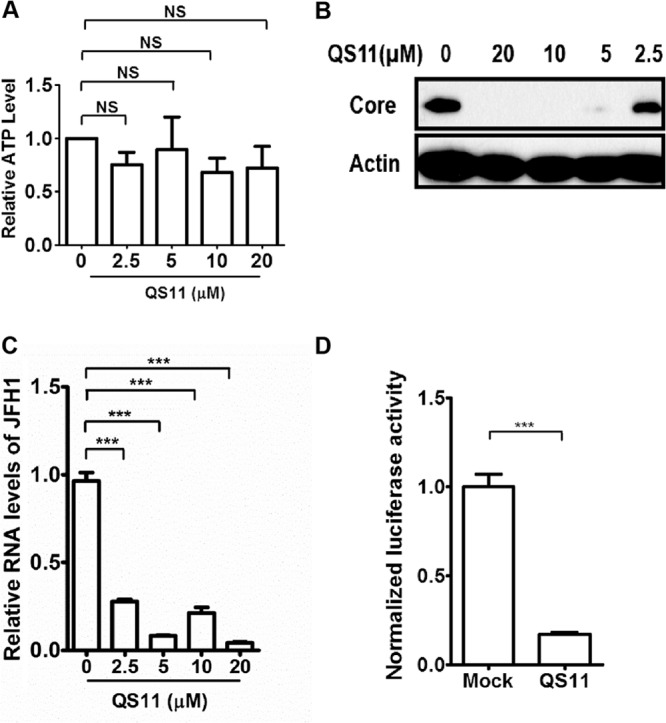

FIG 1.

QS11 inhibits HCV replication. (A) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with different dosages of QS11 for 48 h, and cell viability was determined by measurement of cellular ATP content using the CellTiter-Glo assay. NS, not significant. (B) Huh 7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH1 (MOI = 1) for 2 h, followed by treatment with different dosages of QS11 for 72 h. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) Huh 7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH1 for 2 h and then treated with different dosages of QS11 for 48 h. Relative levels of JFH1 RNA were quantified by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± SEM. ***, P < 0.0001. (D) OR6 cells were incubated with 10 μM QS11 for 48 h. Renilla luciferase activities were measured and normalized to cellular ATP levels. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± SEM. ***, P < 0.0001.

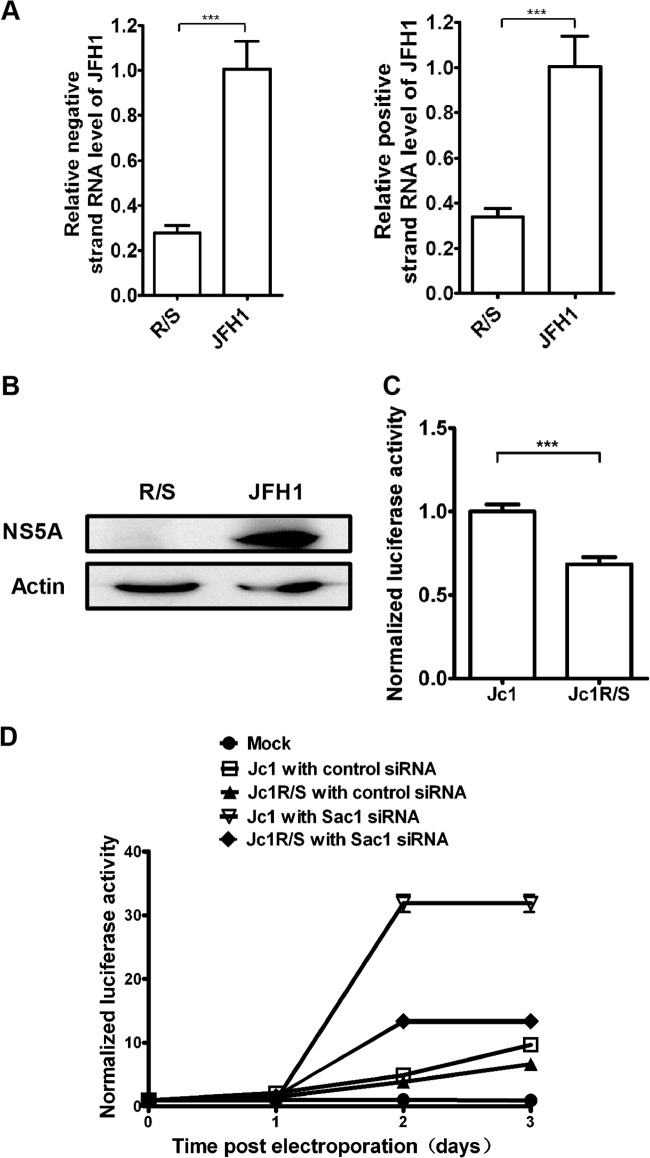

FIG 7.

A tetraarginine motif in NS5A is critical for viral replication. (A) pJFH1 or pJFH1R/S was in vitro transcribed and electroporated into Huh 7.5.1 cells. At day 3, total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed. Relative levels of negative-strand RNA of JFH1, positive-strand RNA of JFH1, and mRNA levels of ARFGAP1 were quantified by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. ***, P < 0.0001. (B) pJFH1 or pJFH1R/S was in vitro transcribed and electroporated into Huh 7.5.1 cells. At day 3, the cell lysates were collected and probed with the indicated antibodies. (C) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with control siRNA for 2 days and then pJFH1 or pJFH1R/S was in vitro transcribed and electroporated into cells. Gaussia luciferase activities were measured and normalized to cellular ATP levels 3 days after electroporation. Data represent the averages from triplicate experiments ± SEM. ***, P < 0.0001. (D) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with Sac1 siRNA or control siRNA for 2 days and then pJFH1 or pJFH1R/S was in vitro transcribed and electroporated into cells. Gaussia luciferase activities were measured and normalized to cellular ATP levels. Data represent the averages from triplicate experiments ± SEM.

RESULTS

ARFGAP1 plays a critical role in HCV replication.

Key components of the COPI transport pathway, including coatomer, GBF1, and ARF1, have been identified as host factors essential for HCV replication (11, 13, 14). To investigate the functional role of ARFGAP1 in HCV replication, we suppressed ARFGAP1 in HCV-infected cells by QS11, an inhibitor selective for ARFGAP1 (22). We first verified that QS11 at a concentration ranging from 2.5 μM to 20 μM for 48 h did not affect the viability of Huh 7.5.1 cells as assessed by cellular ATP levels (Fig. 1A). Next, QS11 at different dosages was added to the medium 2 h postinfection with JFH1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1, and the expression of viral core protein was assessed by immunoblot assay. As shown in Fig. 1B, QS11 effectively inhibited the synthesis of HCV core protein. Likewise, QS11 at 20 μM suppressed the level of viral RNA assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Fig. 1C). To confirm the antiviral activity of QS11 in the HCV replication step, we used an HCV replicon OR6 expressing the Renilla luciferase reporter gene. As shown in Fig. 1D, QS11 inhibited HCV replication in OR6 cells. Together, these results show that the ARFGAP1 inhibitor QS11 has antiviral activity against HCV RNA replication.

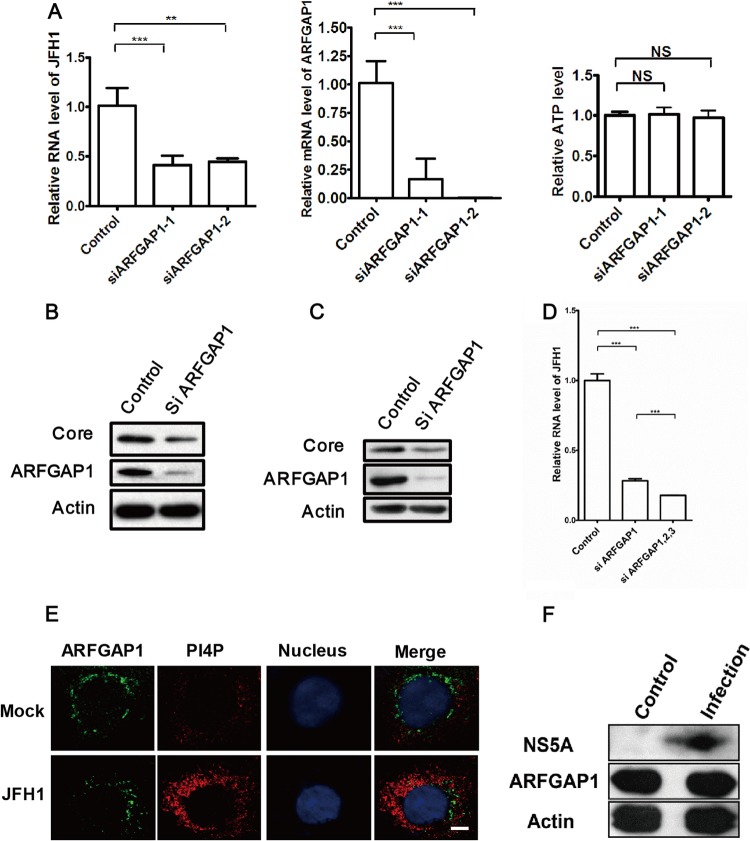

Next, we employed the siRNA strategy to silence the gene expression of ARFGAP1. We found that siRNA-ARFGAP1 reduced the mRNA level of ARFGAP1 without affecting cell viability assessed by the cellular ATP levels (Fig. 2A). Treatment with siRNA-ARFGAP1 resulted in a decrease of the HCV RNA and a moderate decrease of HCV core protein (Fig. 2A and B). Knockdown of ARFGAP1 by siRNA also decreased the protein level of the core in OR6 cells (Fig. 2C). We noticed that silencing ARFGAP1 marginally inhibited HCV replication, while QS11 inhibited HCV replication almost completely. In humans, three ARFGAPs (ARFGAP1, ARFGAP2, and ARFGAP3) are involved in COPI vesicle trafficking (23). It is possible that ARFGAP2 and ARFGAP3 are inhibited by QS11. Indeed, we found that silencing all the ARFGAPs gave greater reduction of viral RNA replication than silencing ARFGAP1 alone (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that ARFGAP1 is a host factor for HCV replication.

FIG 2.

ARFGAP1 is a host factor for HCV replication. (A) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with siRNAs targeting ARFGAP1 or control siRNA for 72 h and then infected with JFH1 (MOI = 1) for another 48 h. Relative levels of JFH1 RNA and ARFGAP1 mRNA were quantified by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Cellular ATP levels were measured to indicate cell viability. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± SEM. NS, not significant; ***, P < 0.0001. (B) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with siRNA targeting ARFGAP1 (ARFGAP1-1) or control siRNA for 72 h and infected with JFH1 (MOI = 1) for another 72 h. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) OR6 cells were treated with siRNA targeting ARFGAP1 (ARFGAP1-1) or control siRNA for 72 h. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (D) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with siRNAs targeting ARFGAP1 (ARFGAP1-1 and ARFGAP1-2), all ARFGAPs (ARFGAP1, ARFGAP2, and ARFGAP3), or control siRNA for 72 h and then infected with JFH1 (MOI = 1) for another 48 h. Relative levels of JFH1 RNA were quantified by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± SEM. NS, not significant; ***, P < 0.0001. (E) Huh 7.5.1 cells infected with JFH1 or mock infected were stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Huh 7.5.1 cells infected with JFH1 or mock infected were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Next, we checked the localization and expression level of ARFGAP1 in cells infected with JFH1. As shown in Fig. 2E, upregulation of the PI4P level marked the JFH1 infection. The ARFGAP1 signal was changed dramatically from the usual perinuclear ribbon in uninfected cells to punctuate fragments dispersed throughout the cytoplasm in JFH1-infected cells (Fig. 2E), though the Western blot signal of ARFGAP1 remained the same (Fig. 2F).

Sac1 inhibited HCV replication.

ARFGAP1 promotes cargo sorting during the formation of COPI vesicles (17). The phosphatidylinositol phosphatase Sac1 recycles from the Golgi membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by interacting with the COPI complex (10). To test whether Sac1 also interacted with ARFGAP1 by coimmunoprecipitation assay, we generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the cytoplasmic tail of Sac1 (amino acids [aa] 570 to 587, NGKDFVDAPRLVQKEKID). Huh 7.5.1 cells were lysed, and the whole protein extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody against Sac1. As shown in Fig. 3A, ARFGAP1 coimmunoprecipitated with Sac1 antibodies with higher efficiency compared to the IgG control. Likewise, Huh 7.5.1 cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibody against ARFGAP1. As shown in Fig. 3B, Sac1 coimmunoprecipitated with ARFGAP1 antibodies with higher efficiency than the IgG control. Taken together, these data suggest that Sac1 associates with ARFGAP1 in Huh 7.5.1 cells.

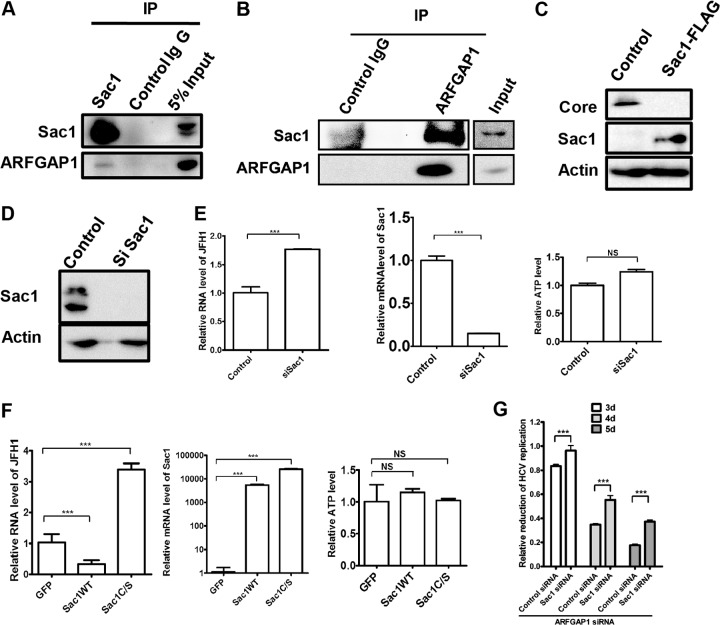

FIG 3.

Sac1 inhibits HCV replication. (A) Lysates of Huh 7.5.1 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-Sac1 antibody or control rabbit IgG and followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) Lysates of Huh 7.5.1 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-ARFGAP1 antibody or control rabbit IgG. Input (5% of total lysate) and immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) Huh 7.5.1 cells were transfected with Sac1-FLAG or empty vector for 24 h and then infected with JFH1 for another 72 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (D) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with siRNA targeting Sac1 or control siRNA for 72 h, and the cell lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies. (E) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with siRNA targeting Sac1 or control siRNA for 72 h and then infected with JFH1 for another 48 h. Relative levels of JFH1 RNA and Sac1 mRNA were determined by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Cellular ATP levels of cells were measured to indicate cell viability. Statistical analyses were performed using a 2-tailed Student t test. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± SEM. NS, not significant; ***, P < 0.0001. (F) Huh 7.5.1 cells were transfected with GFP constructs expressing GFP, Sac1WT, or Sac1C/S for 24 h and infected with JFH1 for another 48 h. Relative levels of JFH1 RNA and Sac1 mRNA were determined by qPCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Cellular ATP levels of cells were measured to indicate cell viability. Data represent the averages from at least three independent experiments ± SEM. NS, not significant; ***, P < 0.0001. (G) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with Sac1/ARFGAP1 siRNA, control/ARFGAP1 siRNA, or control siRNA for 48 h and infected with Jc1FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A). At days 3, 4, and 5 postinfection, Gaussia luciferase activities were measured and normalized to cellular ATP levels. Relative reduction of HCV infection treated with Sac1/ARFGAP1 siRNA or control/ARFGAP1 siRNA was normalized to HCV infection treated with control siRNA. Data represent the averages from triplicate experiments ± SEM. ***, P < 0.0001.

Previously, we showed that depletion of intracellular PI4P by overexpression of Sac1 reduced HCV replication by immunostaining for HCV core and NS5A proteins (11). As shown in Fig. 3C, the level of core protein was significantly reduced in cells transfected with Sac1. To further demonstrate the antiviral role of Sac1, we knocked down the expression of Sac1 by siRNA. We verified that the protein level of Sac1 was reduced by siRNA (Fig. 3D). We also verified the mRNA level of Sac1 was reduced by 85% in siRNA-treated cells as judged by qPCR (Fig. 3E). Silencing Sac1 significantly increased the RNA level of HCV by 77% in infected cells without affecting cell viability assessed by the cellular ATP levels. These data suggest that Sac1 is a negative regulator of HCV replication.

In order to test whether the phosphatase activity of Sac1 is required for its anti-HCV effect, we generated the catalytically inactive mutant, Sac1C/S. As shown in Fig. 3F, expression of Sac1WT could inhibit HCV replication by 70%, while Sac1C/S enhanced HCV replication by 2.4-fold without affecting cell viability as assessed by the cellular ATP levels, suggesting that Sac1C/S plays a dominant negative role compared with Sac1WT. These data suggest that the phosphatase activity is required for the anti-HCV function of Sac1.

Previously, Sac1 has been suggested to be a COPI cargo, so we tested whether reduction of HCV replication by blocking the COPI pathway would be restored by Sac1 siRNA. We treated Huh 7.5.1 cells with Sac1/ARFGAP1 siRNA, control/ARFGAP1 siRNA, or control siRNA for 2 days and then infected them with Jc1FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A). At days 3, 4, and 5 postinfection, HCV replication was measured by Gaussia luciferase activity normalized by cellular ATP level. Relative reduction of HCV infection by Sac1/ARFGAP1 siRNA or control/ARFGAP1 siRNA was normalized to HCV infection treated with control siRNA. As shown in Fig. 3G, knockdown of Sac1 partially rescued the reduction of viral replication by ARFGAP1 siRNA.

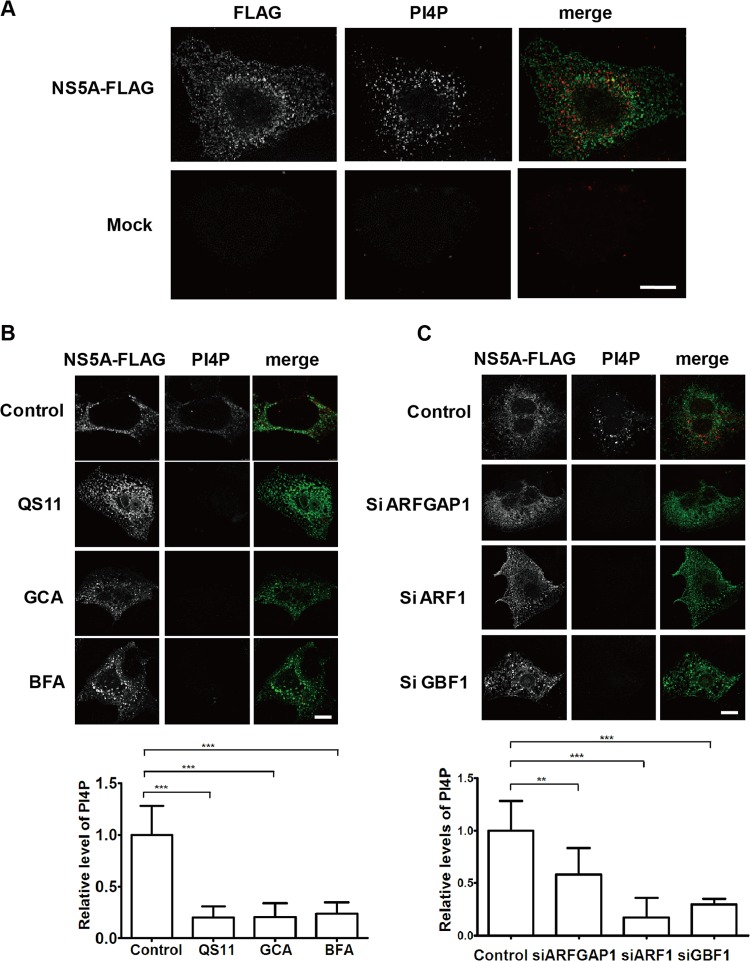

COPI is critical for PI4P production stimulated by NS5A.

Since the COPI cargo Sac1 was involved in HCV replication and the depletion of cellular PI4P, we speculated that the COPI pathway is required for elevated levels of PI4P induced by HCV. To test this hypothesis, we quantified the level of PI4P in cells transfected with NS5A and treated with inhibitors of the COPI pathway, including the ARFGAP1 inhibitor QS11 (22), GBF1 inhibitor GCA (24), and ARF1 inhibitor BFA (25). We confirmed that PI4P levels were upregulated by NS5A in Huh 7.5.1 cells (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, all three inhibitors reduced PI4P synthesis stimulated by NS5A. Next, we knocked down COPI components using siRNAs against ARFGAP1, GBF1, or ARF1 and confirmed that all three COPI-related proteins were required for PI4P induction by NS5A (Fig. 4C). These data suggested that the COPI pathway is crucial for PI4P generation induced by NS5A.

FIG 4.

COPI is important for induction of PI4P by NS5A. (A) Huh 7.5.1 cells were transfected with NS5A-FLAG for 24 h and then stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Huh 7.5.1 cells were transfected with NS5A-FLAG for 24 h and then treated with mock control, QS11 (20 μM), GCA (20 μM), or BFA (2 μg/ml) for 6 h. The cells were stained with the indicated antibodies. The relative level of PI4P in the cells was analyzed using Volocity. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data were collected from at least 20 cells for each condition and represent the averages ± SEM. ***, P < 0.0001. (C) Huh 7.5.1 cells were treated with siRNA control or siRNA against ARFGAP1, GBF1, and ARF1 for 72 h and followed by NS5A-FLAG transfection for 24 h. The cells were stained with the indicated antibodies. Relative levels of PI4P in the cells were analyzed using Volocity. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data were collected from at least 20 cells for each condition and represent the averages ± SEM. **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001.

NS5A interacts with ARFGAP1.

Since Sac1 inhibited HCV replication, we wondered whether HCV evolved a counterdefense strategy to suppress Sac1 function, such as interfering with the ARFGAP1-mediated sorting of Sac1 into COPI vesicles. To screen the HCV protein(s) associated with ARFGAP1, we expressed individual FLAG-tagged HCV proteins and assessed the colocalization of endogenous ARFGAP1 with each viral protein. We found that ARFGAP1 partially colocalized with NS5A (data not shown). To confirm the colocalization of ARFGAP1 and NS5A, we transfected plasmids expressing NS5A-FLAG and ARFGAP1-Myc to Huh 7.5.1 cells and observed a nice overlapping signal (yellow) of two proteins (Fig. 5A).

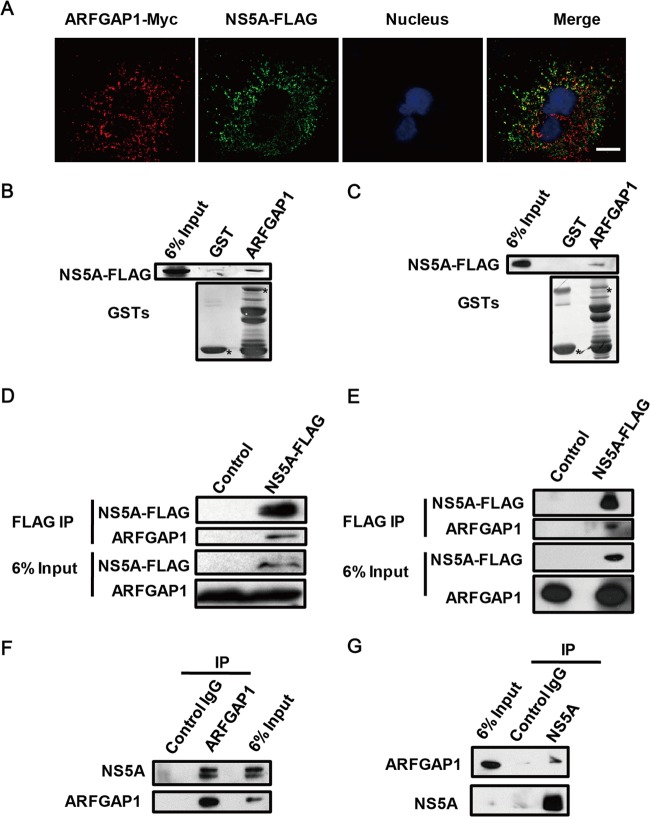

FIG 5.

ARFGAP1 interacts with NS5A. (A) Huh 7.5.1 cells were stained with the indicated antibodies 24 h posttransfection with FLAG-tagged NS5A and ARFGAP1-Myc constructs. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Lysates of NS5A-FLAG-transfected 293T cells were pulled down by GST-ARFGAP1 or GST-bound glutathione agarose beads. Input represented 6% of total lysate. GST or GST fusion proteins are marked by an asterisk. (C) Lysates of NS5A-FLAG-transfected Huh 7.5.1 cells were pulled down by GST-ARFGAP1 or GST-bound glutathione agarose beads. Input represented 6% of total lysate. GST or GST fusion proteins are marked by an asterisk. (D) Lysates of 293T cells transfected with NS5A-FLAG were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and probed with the indicated antibodies. (E) Lysates of Huh 7.5.1 cells transfected with NS5A-FLAG were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and probed with the indicated antibodies. (F) Huh 7.5.1 cells were infected with JFH1 (MOI = 1) for 3 days, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-ARFGAP1 antibody or control rabbit IgG and probed with the indicated antibodies. (G) Huh 7.5.1 cells were infected with Jc1 (MOI = 1) for 3 days, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-NS5A antibody or control rabbit IgG and probed with the indicated antibodies.

Next, we performed GST pulldown experiments using either GST or GST-ARFGAP1 to detect the interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1. NS5A was pulled down by GST-ARFGAP1, whereas the GST control was unable to interact with NS5A in both 293T cells (Fig. 5B) and Huh 7.5.1 cells (Fig. 5C). The interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1 was tested with coimmunoprecipitation experiments. FLAG-tagged NS5A or control vectors were transfected into 293T cells. Cells were lysed, and the soluble cytosolic supernatants were incubated with anti-FLAG-Sepharose. ARFGAP1 was detectable by immunoblotting only in samples with both proteins (NS5A-FLAG and ARFGAP1) (Fig. 5D). We also confirmed that the interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1 was validated in Huh 7.5.1 cells (Fig. 5E). To show the interaction of NS5A and ARFGAP1 in viral infection conditions, JFH1-infected Huh 7.5.1 cells were lysed, and the soluble cytosolic supernatants were incubated with rabbit anti-ARFGAP1 or control rabbit IgG. Endogenous NS5A was detectable by immunoblotting only in samples incubated with anti-ARFGAP1 (Fig. 5F). We also performed an additional experiment in which anti-NS5A is used for immunoprecipitation to confirm that the interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1 was validated in Jc1-infected Huh 7.5.1 cells (Fig. 5G). Taken together, these results demonstrated the existence of a protein complex consisting of NS5A and ARFGAP1.

A tetraarginine motif in NS5A is critical for PI4P induction.

Next, we tested different truncated constructs of NS5A for their binding capacity to ARFGAP1 using the GST pulldown assay. A series of GST fusion proteins were designed, including residues 35 to 215, 35 to 341, or 353 to 444 of NS5A. We chose the fragments of NS5A from JFH1 according to reference 26. Domain I of NS5A is from aa 35 to 215 and domain II of NS5A is from aa 248 to 341. Domain III of NS5A starts at aa 353. Endogenous ARFGAP1 was retained only on GST-NS5A containing the C-terminal fragment (residues 353 to 444) (Fig. 6A). In contrast, residues 35 to 341 of NS5A completely failed to pull down ARFGAP1 (Fig. 6A). These results indicate that residues 353 to 444 of NS5A are sufficient for interaction with ARFGAP1.

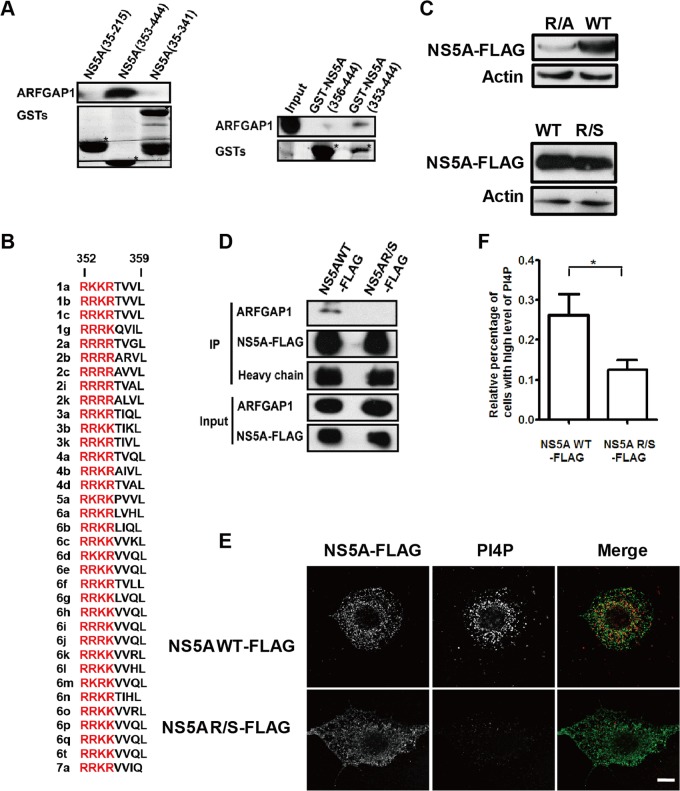

FIG 6.

A tetraarginine motif in NS5A is critical for the interaction between ARFGAP1 and NS5A, PI4P induction, and viral replication. (A) Huh 7.5.1 cell lysates were pulled down by different domains of NS5A fused to the GST tag. Input represented 5% of total lysates. GST or GST fusion proteins are marked by an asterisk. (B) Sequence alignment of different HCV genotypes revealed a conserved cluster of basic amino acids in various combinations of lysine and arginine. (C) The cell lysates from Huh 7.5.1 cells transfected with NS5A-FLAG or NS5AR/S-FLAG for 24 h were probed with the indicated antibodies. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation assays in 293T cells transfected with expression vectors for NS5A-FLAG and NS5AR/S-FLAG. Input (5% of total lysate) and immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (E) Huh 7.5.1 cells transfected with NS5A-FLAG or NS5AR/S-FLAG for 24 h were stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) The relative percentage of cell numbers with stronger PI4P staining from panel E was analyzed using Volocity. Data were collected from at least 20 cells for each condition and represent the averages ± SEM. *, P < 0.05.

We noted a cluster of positively charged amino acids in NS5A, including residues R353, R354, R355, and R356. Aligning the sequences of NS5A from multiple HCV genotypes revealed that this cluster of basic amino acids with various combinations of lysine and arginine is a highly conserved feature of NS5A (Fig. 6B). Because KK or RR is a signature COPI binding motif (27), we evaluated the binding affinity of ARFGAP1 to the C-terminal fragment of NS5A that was triple-arginine truncated (356 to 444). As shown in Fig. 6A, deletion of RRR significantly reduced the affinity of NS5A to ARFGAP1 in the GST pulldown assay, suggesting that the positively charged amino acid motif of NS5A could be recognized by ARFGAP1 in vitro.

Next we tested whether the tetraarginine motif in NS5A is required for association with ARFGAP1 in vivo. To this end, we constructed the NS5AR/A-FLAG mutant, wherein the tetraarginine motif was replaced by tetraalanine, and found that the expression level of NS5AR/A-FLAG was much less than that of NS5AR/S-FLAG when we transfected the same amount of each plasmid to the cells (Fig. 6C). To solve this issue, we constructed the NS5AR/S-FLAG mutant, wherein the tetraarginine motif was replaced by tetraserine, and verified that the expression levels of the two plasmids are the same (Fig. 6C). As shown in Fig. 6D, NS5AR/S failed to bind ARFGAP1, which provided further evidence that the cluster of positively charged amino acids in NS5A is critical for the interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1.

The results given above identified a specific interaction between NS5A and ARFGAP1, providing an opportunity to dissect the role of the COPI pathway in PI4P induction by NS5A. Therefore, we tested the stimulation of PI4P synthesis by the NS5A mutant NS5AR/S compared to that of the NS5AWT. Huh 7.5.1 cells were transfected with NS5AWT or NS5AR/S expression vectors. The number of cells with a high level of PI4P as defined by strong PI4P staining decreased in NS5AR/S-transfected cells compared to that in NS5AWT-transfected cells (Fig. 6E and F), suggesting that the tetraarginine motif in NS5A is critical for PI4P induction.

The tetraarginine motif in NS5A is critical for HCV replication.

To determine whether the tetraarginine motif of NS5A is important for HCV replication, we generated a mutant JFH1R/S by replacing the tetraarginine with tetraserine. After in vitro transcription and electroporation of viral RNA into Huh 7.5.1 cells, we measured both positive- and negative-strand RNA levels of JFH1 by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 7A, viral negative-strand RNA levels of JFH1R/S were reduced by 70% compared with those of wild-type JFH1, and viral positive-strand RNA levels of JFH1R/S were reduced by 64% compared with those of the wild-type JFH1 strand. HCV NS5A protein levels were also reduced in JFH1R/S compared with those in JFH1 (Fig. 7B). We also generated a pJc1FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A)R/S mutant which contains the R/S mutation in NS5A. After in vitro transcription and electroporation of viral RNA into Huh 7.5.1 cells, we assessed the viral replication by Gaussia luciferase activity normalized by cellular ATP level. As shown in Fig. 7C, viral replication of Jc1R/S was reduced compared with that of wild-type Jc1. These data suggested that the tetraarginine motif of NS5A is critical for HCV replication.

Next we tested whether the replication of the R/S mutant could be restored upon knockdown of Sac1. We treated Huh 7.5.1 cells with Sac1 siRNA or control siRNA for 2 days and then electroporated in vitro transcription viral RNA into Huh 7.5.1 cells. The effect of Sac1 silencing was weaker on Jc1R/S than on Jc1 (Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

In mammalian cells, the homeostasis of PI4P is maintained by PI4 kinases and phosphatases. While extensive studies have been focused on the regulation of PI4 kinases by HCV, little is known about whether HCV manipulates the host PI4P phosphatase Sac1. Here, we demonstrate that Sac1 inhibits HCV replication while HCV evolved strategies to subvert the antiviral defense of Sac1. HCV-encoded protein NS5A could regulate ARFGAP1 to maintain the PI4P-enriched viral replication microenvironment in favor of HCV replication.

Although a high level of intracellular PI4P has been demonstrated to be an essential step for HCV replication (4–8, 11, 28, 29), the role of the host transport pathway involved in maintaining PI4P remains unclear. The upregulation of the PI4P level is abolished when the COPI pathway is inhibited (Fig. 4B and C), confirming that COPI machinery is critical for PI4P regulation possibly through regulation of PI4P phosphatase Sac1.

COPI-related proteins are required for the replication of several viruses, including vaccinia virus (19), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (30), and poliovirus (31, 32). The first line of evidence demonstrating a role for COPI in HCV came from a functional genome-wide siRNA screen. The coatomer was initially identified as a host factor for HCV (12). Later, regulators of COPI activity, ARF1 and GBF1, were also found to be critical for HCV replication (11, 13, 14). A major question that has not been conclusively resolved is the mechanism underlying the regulation of HCV infection by COPI-dependent transport. Here, we demonstrate that ARFGAP1, GBF1, and ARF1 are crucial for a high level of PI4P induced by NS5A. The viral NS5A protein recruits ARFGAP1 to maintain a considerable PI4P level in favor of HCV replication, which at least partially explains the participation of the COPI pathway during HCV replication.

Our data demonstrate that the COPI component ARFGAP1 interacts with the virus-encoded protein NS5A (Fig. 5), which stimulates PI4P synthesis at the membranous web for virus replication. Meanwhile, we demonstrate that Sac1 is a COPI cargo recognized by ARFGAP1 (Fig. 3A and B). Thus, during HCV infection, NS5A provides dual function to manipulate the PI4P metabolism: recruiting PI4 kinases to promote PI4P synthesis at the site of virus replication and recruiting ARFGAP1 to displace the PI4P phosphatase to slow the turnover rate of PI4P.

Domain III of NS5A is thought to be dispensable for RNA replication (33). There are different start positions for domain III of NS5A, such as aa 356 (34), aa 355 (35), aa 353 (26), or aa 352 (36). The tetraarginine motif we identified in this study locates from aa 352 to aa 355. We generated two mutant viruses by replacing the tetraarginine with tetraserine and showed that the tetraarginine motif from aa 352 to aa 355 is important for HCV RNA replication.

We identified the tetraarginine motif in NS5A that is required for ARFGAP1 binding, induction of PI4P, and viral replication (Fig. 6 and 7). Moreover, this motif of positively charged amino acids (R or K) is highly conserved in all known genotypes of HCV (Fig. 6B), suggesting a high selection pressure on the COPI-NS5A interaction during HCV replication, probably involving the maintenance of high levels of PI4P.

In summary, HCV exploits the host COPI pathway to achieve efficient viral replication. Sac1 is a negative regulator for HCV replication, whereas ARFGAP1 exerts a positive effect by removing Sac1. During HCV infection, through interaction with ARFGAP1, NS5A could remove Sac1 from the membranous web to maintain high levels of PI4P. Our results not only expand our understanding of how viruses exploit the COPI pathway but also shed new insights into the regulation of PI4P by HCV and suggest possibly new avenues for HCV therapeutics targeting the COPI pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271832), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7132140), the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2013ZX10004-601), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT13007), the Youth Fund of PUMC (2012J03), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Rising Star of PUMC, the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20121106120058), the Intramural Research Program of the Institute of Pathogen Biology, and the CAMS (2012IPB101) to L.Z. and the NIH (AI082630) to R.T.C.

We thank Francis Chisari, Takaji Wakita, Charles Rice, Nobuyuki Kato, Masanori Ikeda, Victor W. Hsu, and Peter Mayinger for reagents. We thank Jing Wang and Ming Bai for insightful comments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Wasley A, Alter MJ. 2000. Epidemiology of hepatitis C: geographic differences and temporal trends. Semin. Liver Dis. 20:1–16. 10.1055/s-2000-9506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moradpour D, Penin F, Rice CM. 2007. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:453–463. 10.1038/nrmicro1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konan KV, Giddings TH, Jr, Ikeda M, Li K, Lemon SM, Kirkegaard K. 2003. Nonstructural protein precursor NS4A/B from hepatitis C virus alters function and ultrastructure of host secretory apparatus. J. Virol. 77:7843–7855. 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7843-7855.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger KL, Kelly SM, Jordan TX, Tartell MA, Randall G. 2011. Hepatitis C virus stimulates the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha-dependent phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate production that is essential for its replication. J. Virol. 85:8870–8883. 10.1128/JVI.00059-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianco A, Reghellin V, Donnici L, Fenu S, Alvarez R, Baruffa C, Peri F, Pagani M, Abrignani S, Neddermann P, De Francesco R. 2012. Metabolism of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha-dependent PI4P Is subverted by HCV and is targeted by a 4-anilino quinazoline with antiviral activity. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002576. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim YS, Hwang SB. 2011. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein interacts with phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type IIIalpha and regulates viral propagation. J. Biol. Chem. 286:11290–11298. 10.1074/jbc.M110.194472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiss S, Rebhan I, Backes P, Romero-Brey I, Erfle H, Matula P, Kaderali L, Poenisch M, Blankenburg H, Hiet MS, Longerich T, Diehl S, Ramirez F, Balla T, Rohr K, Kaul A, Buhler S, Pepperkok R, Lengauer T, Albrecht M, Eils R, Schirmacher P, Lohmann V, Bartenschlager R. 2011. Recruitment and activation of a lipid kinase by hepatitis C virus NS5A is essential for integrity of the membranous replication compartment. Cell Host Microbe 9:32–45. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai AW, Salloum S. 2011. The role of the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase PI4KA in hepatitis C virus-induced host membrane rearrangement. PLoS One 6:e26300. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blagoveshchenskaya A, Mayinger P. 2009. SAC1 lipid phosphatase and growth control of the secretory pathway. Mol. Biosyst. 5:36–42. 10.1039/b810979f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohde HM, Cheong FY, Konrad G, Paiha K, Mayinger P, Boehmelt G. 2003. The human phosphatidylinositol phosphatase SAC1 interacts with the coatomer I complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52689–52699. 10.1074/jbc.M307983200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Hong Z, Lin W, Shao RX, Goto K, Hsu VW, Chung RT. 2012. ARF1 and GBF1 generate a PI4P-enriched environment supportive of hepatitis C virus replication. PLoS One 7:e32135. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tai AW, Benita Y, Peng LF, Kim SS, Sakamoto N, Xavier RJ, Chung RT. 2009. A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 5:298–307. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goueslain L, Alsaleh K, Horellou P, Roingeard P, Descamps V, Duverlie G, Ciczora Y, Wychowski C, Dubuisson J, Rouille Y. 2010. Identification of GBF1 as a cellular factor required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 84:773–787. 10.1128/JVI.01190-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matto M, Sklan EH, David N, Melamed-Book N, Casanova JE, Glenn JS, Aroeti B. 2011. Role for ADP ribosylation factor 1 in the regulation of hepatitis C virus replication. J. Virol. 85:946–956. 10.1128/JVI.00753-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu VW. 2011. Role of ArfGAP1 in COPI vesicle biogenesis. Cell. Logist. 1:55–56. 10.4161/cl.1.2.15175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SY, Yang JS, Hong W, Premont RT, Hsu VW. 2005. ARFGAP1 plays a central role in coupling COPI cargo sorting with vesicle formation. J. Cell Biol. 168:281–290. 10.1083/jcb.200404008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JS, Lee SY, Gao M, Bourgoin S, Randazzo PA, Premont RT, Hsu VW. 2002. ARFGAP1 promotes the formation of COPI vesicles, suggesting function as a component of the coat. J. Cell Biol. 159:69–78. 10.1083/jcb.200206015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Krausslich HG, Mizokami M, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791–796. 10.1038/nm1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Lee SY, Beznoussenko GV, Peters PJ, Yang JS, Gilbert HY, Brass AL, Elledge SJ, Isaacs SN, Moss B, Mironov A, Hsu VW. 2009. A role for the host coatomer and KDEL receptor in early vaccinia biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:163–168. 10.1073/pnas.0811631106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai M, Gad H, Turacchio G, Cocucci E, Yang JS, Li J, Beznoussenko GV, Nie Z, Luo R, Fu L, Collawn JF, Kirchhausen T, Luini A, Hsu VW. 2011. ARFGAP1 promotes AP-2-dependent endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:559–567. 10.1038/ncb2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Jilg N, Shao RX, Lin W, Fusco DN, Zhao H, Goto K, Peng LF, Chen WC, Chung RT. 2011. IL28B inhibits hepatitis C virus replication through the JAK-STAT pathway. J. Hepatol. 55:289–298. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Major MB, Takanashi S, Camp ND, Nishiya N, Peters EC, Ginsberg MH, Jian X, Randazzo PA, Schultz PG, Moon RT, Ding S. 2007. Small-molecule synergist of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7444–7448. 10.1073/pnas.0702136104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saitoh A, Shin HW, Yamada A, Waguri S, Nakayama K. 2009. Three homologous ArfGAPs participate in coat protein I-mediated transport. J. Biol. Chem. 284:13948–13957. 10.1074/jbc.M900749200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saenz JB, Sun WJ, Chang JW, Li J, Bursulaya B, Gray NS, Haslam DB. 2009. Golgicide A reveals essential roles for GBF1 in Golgi assembly and function. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:157–165. 10.1038/nchembio.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu VW, Shah N, Klausner RD. 1992. A brefeldin A-like phenotype is induced by the overexpression of a human ERD-2-like protein, ELP-1. Cell 69:625–635. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90226-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster TL, Belyaeva T, Stonehouse NJ, Pearson AR, Harris M. 2010. All three domains of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural NS5A protein contribute to RNA binding. J. Virol. 84:9267–9277. 10.1128/JVI.00616-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zerangue N, Malan MJ, Fried SR, Dazin PF, Jan YN, Jan LY, Schwappach B. 2001. Analysis of endoplasmic reticulum trafficking signals by combinatorial screening in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:2431–2436. 10.1073/pnas.051630198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu NY, Ilnytska O, Belov G, Santiana M, Chen YH, Takvorian PM, Pau C, van der Schaar H, Kaushik-Basu N, Balla T, Cameron CE, Ehrenfeld E, van Kuppeveld FJ, Altan-Bonnet N. 2010. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell 141:799–811. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishe B, Syed GH, Field SJ, Siddiqui A. 2012. Role of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) and its binding protein GOLPH3 in HCV secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 287:27637–27647. 10.1074/jbc.M112.346569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panda D, Das A, Dinh PX, Subramaniam S, Nayak D, Barrows NJ, Pearson JL, Thompson J, Kelly DL, Ladunga I, Pattnaik AK. 2011. RNAi screening reveals requirement for host cell secretory pathway in infection by diverse families of negative-strand RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:19036–19041. 10.1073/pnas.1113643108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belov GA, Altan-Bonnet N, Kovtunovych G, Jackson CL, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Ehrenfeld E. 2007. Hijacking components of the cellular secretory pathway for replication of poliovirus RNA. J. Virol. 81:558–567. 10.1128/JVI.01820-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wessels E, Duijsings D, Lanke KH, van Dooren SH, Jackson CL, Melchers WJ, van Kuppeveld FJ. 2006. Effects of picornavirus 3A proteins on protein transport and GBF1-dependent COP-I recruitment. J. Virol. 80:11852–11860. 10.1128/JVI.01225-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tellinghuisen TL, Foss KL, Treadaway JC, Rice CM. 2008. Identification of residues required for RNA replication in domains II and III of the hepatitis C virus NS5A protein. J. Virol. 82:1073–1083. 10.1128/JVI.00328-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tellinghuisen TL, Marcotrigiano J, Gorbalenya AE, Rice CM. 2004. The NS5A protein of hepatitis C virus is a zinc metalloprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 279:48576–48587. 10.1074/jbc.M407787200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta G, Qin H, Song J. 2012. Intrinsically unstructured domain 3 of hepatitis C virus NS5A forms a “fuzzy complex” with VAPB-MSP domain which carries ALS-causing mutations. PLoS One 7:e39261. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appel N, Zayas M, Miller S, Krijnse-Locker J, Schaller T, Friebe P, Kallis S, Engel U, Bartenschlager R. 2008. Essential role of domain III of nonstructural protein 5A for hepatitis C virus infectious particle assembly. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000035. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]