ABSTRACT

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein (vFLIP) K13 was originally believed to protect virally infected cells against death receptor-induced apoptosis by interfering with caspase 8/FLICE activation. Subsequent studies revealed that K13 also activates the NF-κB pathway by binding to the NEMO/inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase gamma (IKKγ) subunit of an IKK complex and uses this pathway to modulate the expression of genes involved in cellular survival, proliferation, and the inflammatory response. However, it is not clear if K13 can also induce gene expression independently of NEMO/IKKγ. The minimum region of NEMO that is sufficient for supporting K13-induced NF-κB has not been delineated. Furthermore, the contribution of NEMO and NF-κB to the protective effect of K13 against death receptor-induced apoptosis remains to be determined. In this study, we used microarray analysis on K13-expressing wild-type and NEMO-deficient cells to demonstrate that NEMO is required for modulation of K13-induced genes. Reconstitution of NEMO-null cells revealed that the N-terminal 251 amino acid residues of NEMO are sufficient for supporting K13-induced NF-κB but fail to support tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-induced NF-κB. K13 failed to protect NEMO-null cells against TNF-α-induced cell death but protected those reconstituted with the NEMO mutant truncated to include only the N-terminal 251 amino acid residues [the NEMO(1-251) mutant]. Taken collectively, our results demonstrate that NEMO is required for modulation of K13-induced genes and the N-terminal 251 amino acids of NEMO are sufficient for supporting K13-induced NF-κB. Finally, the ability of K13 to protect against TNF-α-induced cell death is critically dependent on its ability to interact with NEMO and activate NF-κB.

IMPORTANCE Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded vFLIP K13 is believed to protect virally infected cells against death receptor-induced apoptosis and to activate the NF-κB pathway by binding to adaptor protein NEMO/IKKγ. However, whether K13 can also induce gene expression independently of NEMO and the minimum region of NEMO that is sufficient for supporting K13-induced NF-κB remain to be delineated. Furthermore, the contribution of NEMO and NF-κB to the protective effect of K13 against death receptor-induced apoptosis is not clear. We demonstrate that NEMO is required for modulation of K13-induced genes and its N-terminal 251 amino acids are sufficient for supporting K13-induced NF-κB. The ability of K13 to protect against TNF-α-induced cell death is critically dependent on its ability to interact with NEMO and activate NF-κB. Our results suggest that K13-based gene therapy approaches may have utility for the treatment of patients with NEMO mutations and immunodeficiency.

INTRODUCTION

The nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) transcriptional regulation system plays key roles in several biological processes, such as inflammation, apoptosis, wound healing, cellular stress responses, and angiogenesis (1–3). The NF-κB transcription factor family consists of five subunits: p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p105 and its cleaved product, p50), and NF-κB2 (p100 and its cleaved product, p52). Any combination of two out of the five subunits can heterodimerize to form a complex to activate or inhibit expression of a number of genes (4). NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO), also known as the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) kinase gamma (IKKγ) subunit, acts as a noncatalytic scaffold protein and regulatory subunit of the IKK complex, which comprises IKK1/α and IKK2/β. Together with IKKα and IKKβ, IKKγ/NEMO functions as a molecular switch to activate the cellular NF-κB pathway (5).

Dysregulation of NF-κB activity is associated with cancer, inflammatory disorders, and autoimmune metabolic diseases (5, 6). Infection with Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV; also known as human herpesvirus 8 [HHV8]) has been associated with the development of Kaposi's sarcoma and a number of lymphoproliferative disorders, such as primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (7–9). KSHV encodes a latent protein from the open reading frame K13 (ORFK13) that resembles the prodomain of caspase 8/FLICE in containing two tandem death effector domains (DEDs). Proteins with tandem DEDs have been discovered in other viruses as well and are believed to protect virally infected cells from death receptor-induced cell death by blocking the recruitment and/or activation of FLICE/caspase 8 (10–12). Hence, these proteins are collectively referred to as viral FLICE inhibitory proteins (vFLIPs). However, we reported that K13 also possesses the unique ability to activate the NF-κB pathway by interacting with an ∼700-kDa IKK complex which consists of IKK1/IKKα, IKK2/IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ (13, 14). K13 uses the NF-κB pathway to modulate the expression of a number of genes involved in cell proliferation, transformation, cytokine secretion, and protection against growth factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis (15–23). We further reported that NEMO/IKKγ is required for K13-induced NF-κB activation (14), and subsequent structural studies mapped the K13-interacting domain of NEMO/IKKγ to its helical domain containing amino acid residues 196 to 252 (24). However, the region of NEMO/IKKγ that is sufficient to support K13-induced NF-κB is not known at the present, and it is also not known whether K13 can induce gene expression independently of NEMO/IKKγ. Finally, the role of NEMO/IKKγ and NF-κB activation in the protective effect of K13 against death receptor-induced apoptosis has not been studied. In this study, we addressed these unanswered questions about the K13-NEMO/IKKγ interaction and the role played by this interaction in K13-induced gene expression and protection against apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents.

293T and 293FT cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Wild-type (WT) and NEMO−/Y murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained from Inder Verma and Richard Gaynor. Wild-type and NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells were generously provided by Shao-Cong Sun (25), and their identity was previously independently confirmed by immunoblotting for NEMO in our laboratory (26). 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) was bought from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Plasmids and retroviral constructs.

Plasmids for making humanized Gaussia luciferase (hGLuc) fusion constructs LZ-hGLuc[1] and LZ-hGLuc[2] were kindly provided by Stephen Michnick (Université de Montréal) (27, 28). NEMO, IKK1, IKK2, and K13 cDNAs were fused in frame to the NH2- and COOH-terminal fragments of hGLuc to make the constructs NEMO-hGLuc[1], NEMO-hGLuc[2], NEMO(1-246)-hGLuc[2], NEMO(247-419)-hGLuc[2], IKK1-hGLuc[1], IKK2-hGLuc[1], K13-hGLuc[1], and K13-hGLuc[2]. Plasmids encoding WT NEMO or C-terminal Flag epitope-tagged K13 and K13-ERTAM have been described previously (16, 21). A similar approach was used to make vFLIP E8-estrogen receptor 4- hydroxytamoxifen (ERTAM) and vFLIP HS-ERTAM constructs encoding equine herpesvirus 2 and herpesvirus saimiri vFLIPs in fusion with ERTAM, respectively. NEMO truncation mutants were generated by PCR mutagenesis with full-length NEMO as a template, followed by cloning into the MSCVpac retroviral vector (a vector carrying murine stem cell virus [MSCV] and a puromycin N-acetyltransferase resistance gene [pac]). The MSCVhygro retroviral vector (a vector carrying MSCV and a hygromycin resistance gene) expressing Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM has been described previously (16, 21). Recombinant retroviral vectors were generated in 293FT cells and used to generate polyclonal populations of infected cells after selection with puromycin or hygromycin, as described previously (29).

Gene chip human array and data analysis.

We used an Affymetrix human genome gene chip (HG-U133A; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), an oligonucleotide probe-based gene array chip, to check the differential gene expression in Jurkat cells. After background correction, data analysis was done using the PLIER16 (probe logarithmic intensity error) algorithm and the Gene Spring GX11.0 program (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Luciferase reporter assays.

The plasmids encoding hGLuc fusion proteins were cotransfected in a 1:1 ratio (100 ng/well for each plasmid DNA) in 293T cells along with a pRSV/LacZ (β-galactosidase) reporter construct (75 ng/well) as described previously (13). At 48 h posttransfection, cells were lysed in Renilla lysis buffer (Promega), and extracts were used for the measurement of luminescence and β-galactosidase activities. The luciferase activity was measured with native coelenterazine (Nanolight Technology) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline at a 20 μM final concentration using a Synergy H4 plate reader (BioTek). Luciferase activity was normalized relative to β-galactosidase activity to control for the difference in the transfection efficiency.

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed essentially as described previously (29). The primary antibodies used in these experiments were antibodies to NEMO and IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-IκBα (Cell Signaling), GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Ambion), and tubulin (Sigma).

NF-κB binding assay.

The DNA-binding activity of the p65 subunit in the nuclear extracts was measured in triplicate using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based NF-κB DNA-binding assay, as described previously (30).

MTS cell viability assays.

MEFs were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 12 h and subsequently assessed for cell viability using the MTS reagent [3-4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-5-(3-carboxy-methoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt] following the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Percent cell survival was calculated on the basis of the reading of untreated cells, which was set equal to 100%.

Real-time RT-PCR.

WT and NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells expressing the vector or K13-ERTAM were treated with 4OHT for 48 h. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized using the reverse transcriptase enzyme SuperScript II (Invitrogen). Real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with SYBR green and the gene-specific PCR primers listed in Table 1. Samples were run in triplicate, and PCR was performed using an ABI Step One Plus thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH was used as a housekeeping gene, and qRT-PCR data (threshold cycle [CT] values) were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method described earlier (30). The qRT-PCR data are presented as the fold change in target gene expression ± standard error of mean.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR (mRNA expression)

| Primer no. | Primer name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | TNFSF10 Forward | ACCAGAGGAAGAAGCAACACAT |

| 2 | TNFSF10 Reverse | GAGTTTATTTTGCGGCCCAGAG |

| 3 | BIRC3 Forward | ACTTGAACAGCTGCTATCCACATC |

| 4 | BIRC3 Reverse | GTTGCTAGGATTTTTCTCTGAACTGTC |

| 5 | NFKB1A Forward | TTACCCTCACCTTTTACTTCACATC |

| 6 | NFKB1A Reverse | AATGCAAGAGAGACCAGAGAAAGTA |

| 7 | GAPDH Forward | TACTAGCGGTTTTACGGGCG |

| 8 | GAPDH Reverse | TCGAACAGGAGGAGCAGAGAGCGA |

Statistical analyses.

Two-tailed paired Student's t test was used to test for differences between two groups. Differences with a P value of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated a minimum of two times with duplicate or triplicate samples.

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data have been deposited with the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE49245.

RESULTS

NEMO is essential for induction of K13-induced genes.

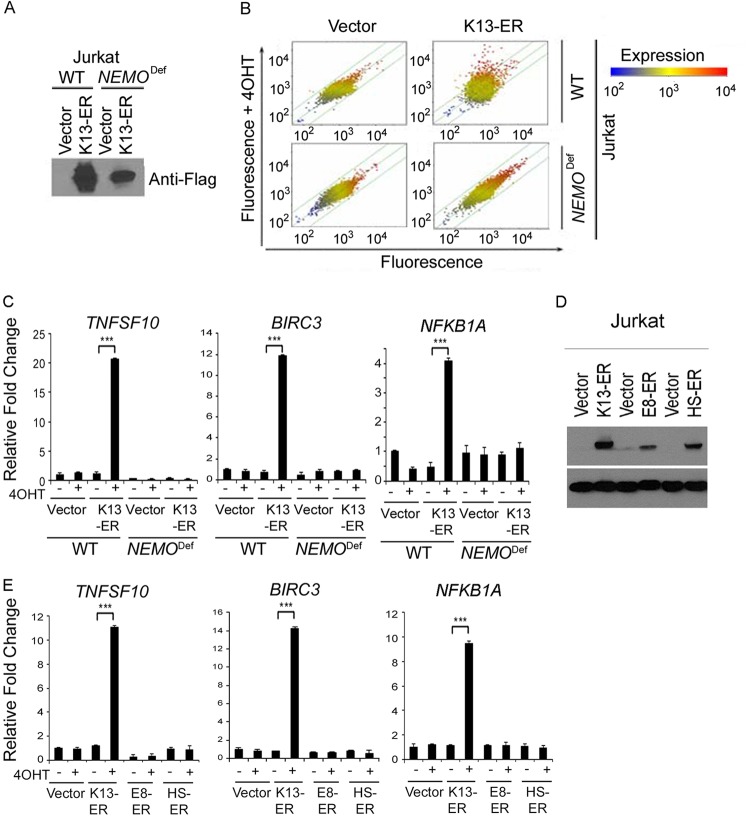

We have previously demonstrated that NEMO is essential for the activation of the NF-κB pathway by K13 (14). However, K13 has also been reported to modulate the expression of genes belonging to the STAT signaling pathway (31), thereby raising the possibility that it could affect gene expression independently of NEMO. To address this question, we used the Affymetrix gene chip HG-U133A array to compare the effect of K13 on gene expression in WT and NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells. We generated stable populations of WT and NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells expressing a Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM fusion construct that expresses the K13 cDNA in frame with the ligand-binding domain of a mutated estrogen receptor (Fig. 1A). The fusion construct allows regulation of K13 activity at the posttranslational level in a 4OHT-dependent fashion (21). The expression of 90 transcripts, including several known NF-κB target genes, was affected more than 2-fold upon 4OHT treatment in K13-ERTAM-expressing WT cells (Fig. 1B). The top 47 genes affected by 4OHT treatment are shown in Table 2. In contrast, the expression of only one gene (PYGL) was significantly affected by 4OHT treatment in the K13-ERTAM-expressing NEMO-deficient cells (Fig. 1B). To confirm the results of microarray analysis, we selected 3 genes (TNFSF10, BIRC3, and NFKB1A) that were significantly upregulated by 4OHT treatment in K13-ERTAM-expressing WT cells and used qRT-PCR to compare their expression. As shown in Fig. 1C, the expression of all 3 genes was significantly upregulated by 4OHT in K13-ERTAM-expressing WT Jurkat cells but not in those deficient in NEMO. It was conceivable that upregulation of the above-described genes was due to the effect of 4OHT on the ERTAM fusion partner rather than activation of K13-induced NF-κB activity. To rule out this possibility, we took advantage of vFLIPs encoded by equine herpesvirus 2 (vFLIP E8) and herpesvirus saimiri (vFLIP HS) that resemble K13 in structure but lack the ability to activate the NF-κB pathway (13). We generated stable clones of WT Jurkat cells expressing vFLIP E8-ERTAM and vFLIP HS-ERTAM fusion constructs and confirmed their expression by Western blotting (Fig. 1D). We next used qRT-PCR to compare the ability of the vFLIP K13-ERTAM, vFLIP E8-ERTAM, and vFLIP HS-ERTAM fusion proteins to induce the expression of the TNFSF10, BIRC3, and NFKB1A genes following treatment with 4OHT. As shown in Fig. 1E, while 4OHT significantly induced the expression of all 3 genes in Jurkat cells expressing K13-ERTAM, it failed to do so in those expressing the vFLIP E8-ERTAM and vFLIP HS-ERTAM fusion proteins. Collectively, these results demonstrate that NEMO is essential for the induction of almost all genes affected by K13 expression and that the NF-κB pathway is the major pathway activated by K13.

FIG 1.

NEMO is essential for induction of K13-induced genes in Jurkat cells. (A) Immunoblot showing expression of Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM (K13-ER) in WT and NEMO-deficient (NEMODef) Jurkat cells. (B) Scatter plot analyses of genes induced by 4OHT treatment in the control vector and K13-ERTAM-expressing WT and NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells. Each point on the scatter plots represents the expression of an individual mRNA message, as determined by units of fluorescence intensity, in untreated cells (x axis) plotted against its expression after 4OHT treatment (y axis). The lines on the scatter plot indicate the 2-fold boundaries used for selecting genes with differential expression. (C) To validate the gene array data, 3 genes, TNFSF10, BIRC3, and NFKB1A, were randomly selected, and their relative mRNA levels in mock- and 4OHT-treated vector- and K13-ERTAM-expressing WT and NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells were examined after 24 h of treatment using qRT-PCR. Real-time PCRs were performed in triplicate, and the data are presented as the fold change (mean ± SE) in target gene expression (***, P < 0.001, Student's t test). (D) Immunoblot showing expression of Flag-tagged vFLIP E8-ERTAM and vFLIP HS-ERTAM in WT Jurkat cells. (E) The relative mRNA levels of TNFSF10, BIRC3, and NFKB1A in mock- and 4OHT-treated vector- and vFLIPs-ERTAM-expressing Jurkat cells were examined after 16 h of 4OHT treatment, as described for panel C.

TABLE 2.

Summary of differentially regulated gene clusters in 4OHT-treated K13-ERTAM-transduced WT Jurkat cells

| No. | Entrez Gene no. | Gene symbol | Gene title | Fold change in expression | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8743 | TNFSF10 | TNF (ligand) superfamily member 10 | 8.45 | Up |

| 2 | 4050 | LTB | Lymphotoxin beta (TNF superfamily member 3) | 7.24 | Up |

| 3 | 330 | BIRC3 | Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 3 | 6.34 | Up |

| 4 | 3627 | CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | 5.93 | Up |

| 5 | 4792 | NFKBIA | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cell inhibitor alpha | 4.87 | Up |

| 6 | 2202 | EFEMP1 | Epidermal growth factor-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 | 4.01 | Up |

| 7 | 6446 | SGK1 | Serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 | 3.86 | Up |

| 8 | 64759 | TNS3 | Tensin 3 | 3.72 | Up |

| 9 | 11221 | DUSP10 | Dual-specificity phosphatase 10 | 3.67 | Up |

| 10 | 64135 | IFIH1 | Interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 | 3.63 | Up |

| 11 | 80833 | APOL3 | Apolipoprotein L protein 3 | 3.56 | Up |

| 12 | 23504 | RIMBP2 | RIMS binding protein 2 | 3.53 | Up |

| 13 | 8870 | IER3 | Immediate early response protein 3 | 3.49 | Up |

| 14 | 7093 | TLL2 | Tolloid-like protein 2 | 3.37 | Up |

| 15 | 7128 | TNFAIP3 | TNF-α-induced protein 3 | 3.23 | Up |

| 16 | 1776 | DNASE1L3 | DNase I-like protein 3 | 3.19 | Up |

| 17 | 5971 | RELB | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog B | 3.09 | Up |

| 18 | 1524 | CX3CR1 | Chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor 1 | 3.08 | Up |

| 19 | 4791 | NFKB2 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 2 (p49/p100) | 2.98 | Up |

| 20 | 649159 | LINC00273 | Long intergenic non-protein-coding RNA 273 | 2.96 | Up |

| 21 | 355 | FAS | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily member 6) | 2.90 | Up |

| 22 | 5774 | PTPN3 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor type 3 | 2.87 | Up |

| 23 | 10133 | OPTN | Optineurin | 2.80 | Up |

| 24 | 6385 | SDC4 | Syndecan 4 | 2.76 | Up |

| 25 | 56967 | C14orf132 | Chromosome 14 open reading frame 132 | 2.75 | Up |

| 26 | 3904 | LAIR2 | Leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 2 | 2.74 | Up |

| 27 | 602 | BCL3 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma protein 3 | 2.72 | Up |

| 28 | 1361 | CPB2 | Carboxypeptidase B2 (plasma) | 2.70 | Up |

| 29 | 57824 | HMHB1 | Histocompatibility (minor) HB-1 | 2.68 | Up |

| 30 | 4049 | LTA | Lymphotoxin alpha (TNF superfamily member 1) | 2.68 | Up |

| 31 | 7293 | TNFRSF4 | TNF receptor superfamily member 4 | 2.67 | Up |

| 32 | 9603 | NFE2L3 | Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived protein 2)-like protein 3 | 2.64 | Up |

| 33 | 6691 | SPINK2 | Serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 2 (acrosin-trypsin inhibitor) | 2.61 | Up |

| 34 | 9050 | PSTPIP2 | Proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 2 | 2.59 | Up |

| 35 | 9308 | CD83 | CD83 molecule | 2.50 | Up |

| 36 | 91304 | C19orf6 | Chromosome 19 open reading frame 6 | 2.47 | Up |

| 37 | 55008 | HERC6 | HECT and RLD domain-containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase family member 6 | 2.47 | Up |

| 38 | 1475 | CSTA | Cystatin A (stefin A) | 2.43 | Up |

| 39 | 55601 | DDX60 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 60 | 2.41 | Up |

| 40 | 4940 | OAS3 | 2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase 3, 100 kDa | 2.36 | Up |

| 41 | 54739 | XAF1 | XIAP-associated factor 1 | 2.36 | Up |

| 42 | 18 | ABAT | 4-Aminobutyrate aminotransferase | 2.35 | Up |

| 43 | 2841 | GPR18 | G protein-coupled receptor 18 | 2.35 | Up |

| 44 | 3001 | GZMA | Granzyme A (granzyme 1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated serine esterase 3) | 2.11 | Down |

| 45 | 182 | JAG1 | Jagged 1 | 2.10 | Down |

| 46 | 2840 | GPR17 | G protein-coupled receptor 17 | 2.08 | Down |

| 47 | 55679 | LIMS2 | LIM and senescent cell antigen-like domains 2 | 2.02 | Down |

Use of GLuc PCA to study K13-NEMO interaction.

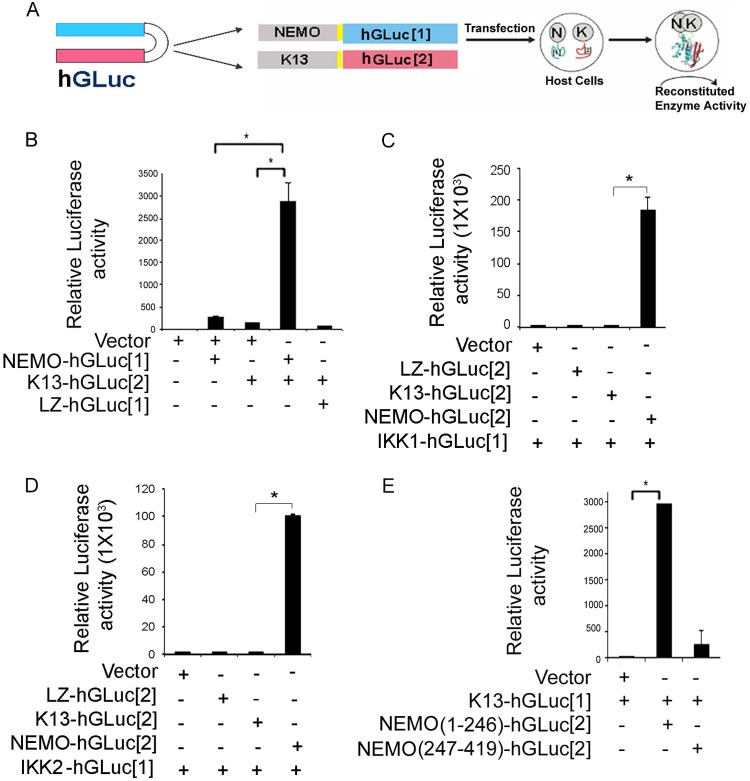

We next developed a protein complementation assay (PCA) to measure the K13-NEMO interaction. A PCA involves the use of rationally dissected reporter proteins and provides an extremely versatile platform to study protein-protein interactions (27, 28). In this strategy, the cDNA encoding a reporter protein is split into two parts and the end of each reporter cDNA fragment is separately fused in frame to two test proteins that are suspected to interact (27, 28). The two cDNA fusion expression cassettes are coexpressed in cells. In case the two test proteins interact, the fragments of the reporter protein are brought together and spontaneously refold into the native structure, generating a measurable signal (27, 28). To study the interaction between K13 and NEMO, we took advantage of a PCA based on the humanized Gaussia luciferase (hGLuc) protein (27). We fused NEMO and K13 cDNAs in frame to the NH2- and COOH-terminal fragments of hGLuc to make the constructs NEMO-hGLuc[1] and K13-hGLuc[2], respectively (Fig. 2A). The two constructs were transfected into 293T cells either individually or in combination, and reconstitution of hGLuc activity in the cell lysates was determined at approximately 48 h posttransfection. As a positive control, we analyzed the reconstitution of hGLuc activity by fusing its two fragments to the GCN4 leucine zipper (LZ) domain. As shown in Fig. 2B, while expression of NEMO-hGLuc[1] and K13-hGLuc[2] alone did not result in significant luciferase activity, coexpression of the two fusion proteins resulted in an approximately 100-fold increase in luciferase activity, indicating reconstitution of hGLuc activity by physical interaction between NEMO and K13 (Fig. 2B). However, no detectable hGLuc activity was measured in cells coexpressing LZ-hGLuc[1] with K13-hGLuc[2], confirming that the PCA reporter fragments do not assemble spontaneously (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

hGLuc protein complementation assay for detecting K13-NEMO interaction. (A) Schematic representation of GLuc protein complementation assay for detecting K13-NEMO interaction. The NH2- and COOH-terminal fragments of humanized GLuc (blue and red, respectively) are fused individually to the COOH termini of NEMO and K13 via a small linker (shown in yellow). Coexpression of the two fragments in a host cell results in interaction between NEMO (N) and K13 (K), which leads to folding of the hGLuc fragment into its native structure and the reconstitution of hGLuc activity. (B) Coexpression of an empty vector, NEMO-hGLuc[1], K13-hGLuc[2], or the LZ-hGLuc[1] control in 293T cells results in the reconstitution of hGLuc activity when full-length NEMO and K13 are present, while expression of the fusion proteins or the LZ-hGluc[1] control individually fails to do so. (C, D) hGLuc PCA assay showing that NEMO-hGLuc[2] strongly interacts with IKK1-hGLuc[1] and IKK2-hGLuc[1], while K13-hGLuc[2] fails to do so. (E) K13 interacts with NEMO(1-246) but does not effectively interact with NEMO(247-419), as determined by hGLuc PCA. 293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs along with a respiratory syncytial virus–β-galactosidase construct. hGLuc activity was measured in cell lysates at approximately 48 h posttransfection and normalized on the basis of the β-galactosidase activity. Values shown are the mean ± SD from one representative experiment out of three performed in duplicate (*, P < 0.05, Student's t test).

We have previously shown that NEMO is essential for mediating the interaction of K13 with IKK1 and IKK2 (26). To further validate the hGLuc PCA, we used it to examine the interaction of K13 and NEMO with IKK1 and IKK2. As shown in Fig. 2C and D, we failed to observe a major increase in hGLuc activity upon coexpression of K13-hGLuc[2] with either IKK1-hGLuc[1] or IKK2-hGLuc[1]. However, coexpression of NEMO-hGLuc[2] with both IKK1-hGluc[1] and IKK2-hGLuc[1] resulted in a robust increase in hGLuc activity (Fig. 2C and D). Taken collectively, these results confirm our previous model that K13 does not directly interact with IKK1 and IKK2 and provide additional validation of the hGLuc PCA.

Use of hGLuc PCA to map the domain of NEMO that interacts with K13.

NEMO consists of two helix-loop-helix domains (HLX1 and HLX2), two coiled coil domains (CCL1 and CCL2), an LZ domain, a NEMO ubiquitin-binding (NUB) domain, a proline-rich (Pro) region, and a zinc finger (ZF) domain (24). The crystal structure of the K13-NEMO complex has been resolved and has revealed that K13-NEMO interaction involves DED1 of K13 and the helical domain HLX2 of human NEMO comprising its amino acid residues 196 to 252 (24). Additional modeling studies have suggested that a short segment of HLX2, consisting of residues 232 to 246, may be primarily responsible for interaction with K13 (24). To confirm this hypothesis, we fused two different fragments of NEMO encompassing residues 1 to 246 [NEMO(1-246)] and 247 to 419 [NEMO(247-419)], respectively, to hGLuc[2] and tested the ability of the constructs to interact with K13-hGLuc[1] using hGLuc PCA. As shown in Fig. 2E, we detected strong reconstitution of hGLuc activity when K13-hGLuc[1] was coexpressed with NEMO(1-246)-hGLuc[2] but not when it was coexpressed with NEMO(247-419)-hGLuc[2]. Collectively, these results confirm the findings of the modeling studies and demonstrate the usefulness of the hGLuc PCA as a rapid and sensitive assay for studying the K13-NEMO interaction.

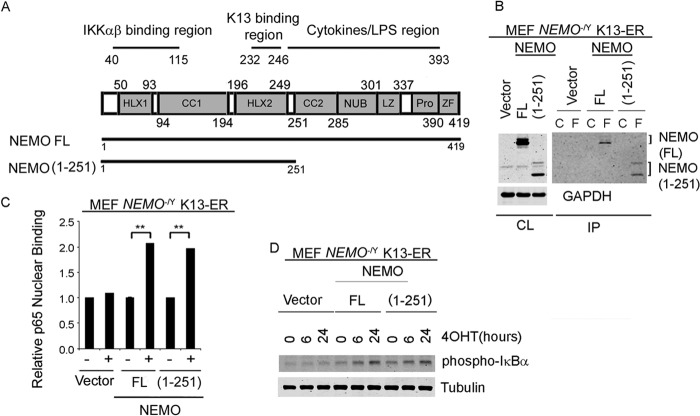

NEMO truncation mutant NEMO(1-251) supports K13-induced NF-κB activation.

In order to confirm the results of hGLuc PCA, we used retrovirus-mediated gene transfer to stably express Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM in NEMO-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NEMO−/Y MEFs). In the resulting NEMO−/Y K13-ERTAM cells, we stably expressed hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged full-length NEMO (NEMO FL) and the NEMO mutant truncated to include only the N-terminal 251 amino acid residues [NEMO(1-251)]. As shown in Fig. 3A, NEMO(1-251) lacks the NUB, LZ, proline-rich, and ZF domains. We chose the NEMO(1-251) mutant for these experiments, as preliminary studies indicated that the NEMO(1-246) mutant was expressed at significantly reduced levels compared to the NEMO FL protein (data not shown). To confirm the results of hGLuc PCA, we next used a coimmunoprecipitation assay to study the interaction between Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM and the NEMO FL and NEMO(1-251) proteins. Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM was immunoprecipitated using Flag or control antibody beads, and its interaction with the NEMO FL and NEMO(1-251) proteins was detected by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3B, robust and nearly equivalent amounts of the NEMO FL and NEMO(1-251) proteins coimmunoprecipitated with K13-ERTAM. K13 activates the NF-κB pathway by activating the IKK complex that phosphorylates IκBα, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (14). This enables NF-κB subunits, such as p65, to translocate to the nucleus, bind DNA, and activate transcription of NF-κB target genes. As shown in Fig. 3C and D, 4OHT treatment of K13-ERTAM-expressing NEMO−/Y MEFs reconstituted with the NEMO FL and NEMO(1-251) proteins resulted in equivalent increases in p65 DNA-binding activity, which were accompanied by a nearly equivalent increase in the phosphorylation of IκBα. Taken together, these results demonstrate that amino acid residues 1 to 251 of NEMO are sufficient to interact with K13 and to support K13-induced NF-κB activation.

FIG 3.

NEMO(1-251) supports K13-induced NF-κB pathway activation. (A) (Top) Schematic representation of NEMO/IKKγ domains showing its two helices (HLX1 and HLX2), two coiled-coil domains (CC1 and CC2), NEMO ubiquitin-binding (NUB) domain, a leucine zipper (LZ) domain, and a zinc finger (ZF) domain. The regions of NEMO involved in binding to IKKα/β and K13 and cytokine/LPS signaling are also shown. (Bottom) The NEMO(1-251) mutant with a truncated C terminus. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation assay showing that K13 interacts with NEMO FL and NEMO(1-251). Flag-tagged K13-ERTAM was immunoprecipitated from NEMO-deficient MEFs reconstituted with an empty vector, NEMO FL, or NEMO(1-251) using control (lanes C) or Flag (lanes F) antibody beads, and the presence of coimmunoprecipitated NEMO was detected by immunoblotting. All samples were treated with 20 nM 4OHT for 48 h prior to lysate preparation. Results are representative of those from two independent experiments. CL, cell lysates; IP, immunoprecipitation. (C) An ELISA-based NF-κB binding assay showing increased p65/RelA DNA-binding activity in the nuclear extracts of K13-ERTAM-expressing NEMO−/Y MEFs reconstituted with NEMO FL and NEMO(1-251) upon 72 h of treatment with 20 nM 4OHT. Values shown are the mean ± SD from one representative experiment out of three performed in triplicate (**, P < 0.01, Student's t test). (D) Whole-cell lysates from MEFs coexpressing K13-ERTAM and either the vector alone, NEMO FL, or NEMO(1-251) were examined for NF-κB activation by Western blotting using an antibody against phospho-IκBα and tubulin as a loading control. MEFs were treated with 20 nM 4OHT for the indicated time intervals prior to lysate preparation. Results are representative of those from two independent experiments.

NEMO(1-251) does not support TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation.

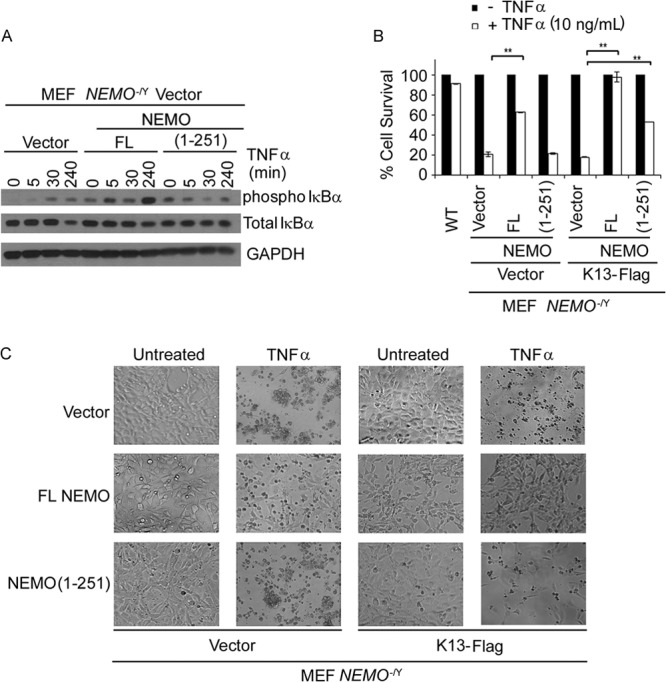

We next asked the question whether the NEMO(1-251) mutant is also capable of supporting NF-κB activation by proinflammatory cytokines. To examine this possibility, we treated NEMO−/Y MEFs that had been reconstituted with an empty vector, NEMO FL, and NEMO(1-251) with TNF-α and examined NF-κB activation by measuring the phosphorylation of IκBα. As shown in Fig. 4A, increased phosphorylation of IκBα was readily apparent in NEMO−/Y MEFs reconstituted with NEMO FL as early as 5 min following TNF-α treatment and was markedly increased at 4 h posttreatment. However, no increase in TNF-α-induced IκBα phosphorylation was apparent in NEMO−/Y MEFs reconstituted with NEMO(1-251). Thus, in contrast to its ability to support K13-induced NF-κB, the NEMO(1-251) mutant is incapable of supporting TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation.

FIG 4.

Truncation mutant NEMO(1-251) fails to support TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation. (A) Whole-cell lysates from MEFs coexpressing K13 and either an empty vector, NEMO FL, or NEMO(1-251) were examined for NF-κB activation upon TNF-α treatment (10 ng/ml) at various time points (0, 5, 30, 240 min) by Western blotting using antibodies against phospho-IκBα and total IκBα and antibody against GAPDH as a loading control. (B) NEMO−/Y MEFs reconstituted with an empty vector, NEMO FL, or NEMO(1-251) and coexpressing the vector or K13-Flag were left untreated or treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 12 h, and cell viability was measured using an MTS assay. WT MEFs were used as a control. Values shown are the mean ± SD from one representative experiment out of three performed in duplicate (**, P < 0.01, Student's t test). (C) NEMO−/Y MEFs coexpressing the empty vector, NEMO FL, or NEMO(1-251) and the vector or K13-Flag were treated with TNF-α as described for panel A and imaged using a phase-contrast microscope. Magnification, ×10. Results are representative of those from three independent experiments.

NF-κB activation is known to protect cells against TNF-α-induced apoptosis, and accordingly, NEMO-deficient cells are known to be highly sensitive to TNF-α (32). As such, to provide further proof of the inability of the NEMO(1-251) mutant to support TNF-α-induced NF-κB, we compared the survival of NEMO−/Y MEFs reconstituted with an empty vector, NEMO FL, and NEMO(1-251) following treatment with TNF-α. Consistent with their inability to support TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation, NEMO−/Y MEFs were highly sensitive to TNF-α-induced cell death compared to the WT MEFs (Fig. 4B and C). Reconstitution with NEMO FL significantly increased the resistance of NEMO−/Y MEFs to TNF-α-induced apoptosis, reflecting the protective effect of TNF-α-induced NF-κB (Fig. 4B and C). However, consistent with its inability to support TNF-α-induced NF-κB, reconstitution with NEMO(1-251) failed to confer protection against TNF-α-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4B and C).

NEMO and NF-κB activation are essential for the protective effect of K13 against TNF-α-induced cell death.

On the basis of its structural homology to the prodomain of caspase 8/FLICE, K13 was originally believed to act as a vFLIP and protect cells against death receptor-induced apoptosis by blocking caspase 8 activation (10–12). However, K13-induced NF-κB is known to induce the expression of a number of antiapoptotic proteins, such as cellular FLICE inhibitory protein (cFLIP) and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (cIAPs) (33–35). Therefore, it is not clear whether the protective effect of K13 against death receptor-induced apoptosis is due to its inhibition of caspase 8 activation or an indirect consequence of K13-induced NF-κB activity and the resulting upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins. As NEMO(1-251) can support K13-induced NF-κB but cannot support TNF-α-induced NF-κB, we used it as a molecular tool to distinguish between the above-described possibilities. For this purpose, we examined the ability of K13 to protect against TNF-α-induced cell death in NEMO−/Y MEFs that had been reconstituted with an empty vector, NEMO FL, and NEMO(1-251). K13 failed to protect NEMO−/Y MEFs expressing an empty vector against TNF-α-induced cell death, indicating the need for its interaction with NEMO and the resultant NF-κB activation in its protective effect (Fig. 4B and C). On the other hand, K13 conferred significant protection against TNF-α-induced cell death in NEMO−/Y MEFs which had been reconstituted with the NEMO(1-251) mutant, which is capable of supporting K13-induced NF-κB but not TNF-α-induced NF-κB (Fig. 4B and C). Finally, coexpression of K13 with NEMO FL, which supports both K13- and TNF-α-induced NF-κB, conferred nearly complete protection against TNF-α-induced cell death (Fig. 4B and C). Taken collectively, these results demonstrate that the protective effect of K13 against TNF-α-induced apoptosis is critically dependent on its interaction with NEMO and the resultant NF-κB activation.

DISCUSSION

KSHV infection is the most common cause of malignancies among patients infected with HIV, and coinfection is a common affliction among young individuals in many parts of the world (36, 37). The K13 protein is one of the few KSHV proteins to be expressed in latently infected Kaposi's sarcoma spindle and PEL cells and a prime candidate for playing a causative role in the pathogenesis of KSHV-associated malignancies (38, 39). On the basis of its homology to the prodomain of FLICE/caspase 8, K13 was originally believed to primarily act as a viral FLICE inhibitory protein that protected virally infected cells against death receptor-induced apoptosis (10–12). Subsequently, K13 was shown to be a strong activator of the NF-κB pathway, and a number of its biological activities were found to be mediated through NF-κB activation (15–23). K13 activates the NF-κB pathway by binding to the NEMO/IKKγ subunit of the IKK complex, and we have previously shown that K13-induced NF-κB activation is defective in NEMO-deficient cells (29). However, recent studies suggest that K13 may also affect the expression of genes belonging to other signaling pathways, such as STAT and interferon (IFN) pathways (31). Therefore, while the requirement for NEMO in the induction of NF-κB-responsive genes by K13 is proven, it is not clear whether NEMO is required for modulation of all genes affected by K13 expression. In this study, we used NEMO-deficient Jurkat cells to demonstrate that NEMO is essential for modulation of almost all genes affected by K13. These results suggest that the activation of STAT/IFN-responsive genes by K13 expression observed in vascular endothelial cells could be an indirect consequence of NEMO/NF-κB-induced upregulation of cytokines and chemokines, which in turn activated STAT signaling by acting in an autocrine and/or paracrine fashion. However, NEMO has also been reported to be essential for virus-induced activation of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and IRF7 (40). Therefore, it is also conceivable that the interaction of K13 with NEMO results in the activation of not only NF-κB but also the IRF signaling pathway.

The crystal structure of the K13-NEMO complex suggested that K13-NEMO interaction involves DED1 of K13 and helical domain HLX2 of NEMO, comprising its amino acid residues 196 to 252 (24). Consistent with the results of the crystal structure, we demonstrate that the N-terminal 1 to 251 amino acids of NEMO not only are responsible for its interaction with K13 but also are sufficient to support K13-induced NF-κB activation. This region spans the IKKα/β binding domain (residues 40 to 115) but lacks the cytokine/lipopolysaccharide (LPS) domain and the ubiquitin-binding domains (41). Consistent with the lack of cytokine/LPS and ubiquitin-binding domains, the NEMO(1-251) mutant could support K13-induced NF-κB activation but failed to support TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation. Collectively, these results confirm our previous findings that K13 activates NF-κB via a mechanism that is not dependent on binding of linear or Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains to NEMO and is distinct from that utilized by inflammatory cytokines (26). However, it is important to point out that although our results demonstrate that the N-terminal 1 to 251 amino acids of NEMO are sufficient to support K13-induced NF-κB activation, they do not entirely rule out a role for the C-terminal domain of NEMO in K13-induced NF-κB signaling. Thus, it is conceivable that the NEMO amino acid residues beyond residue 251 also contribute to K13-induced NF-κB signaling by modulating the magnitude and duration of the response or by controlling the expression of a subset of NF-κB-responsive genes.

Although the NEMO fragment from amino acids 196 to 252 has been shown to be sufficient to bind to K13 (24), we did not test the ability of the corresponding NEMO mutant to support K13-induced NF-κB in the present study for two reasons. First, we have previously shown that IKKα and IKKβ are essential for supporting K13-induced NF-κB (29). However, since the IKKα/β binding region of NEMO spans its residues 40 to 115, the mutant of NEMO consisting of residues 196 to 252 is not expected to bind to IKKα/β and therefore is not expected to support K13-induced NF-κB. Second, we did try to reconstitute NEMO−/Y MEFs with an HA-tagged NEMO(192-252) mutant. However, we could not detect the expression of this shorter mutant on Western blotting (data not shown) and therefore did not pursue further work with this construct.

Mutations in NEMO have been linked to the pathogenesis of a number of genetic disorders that result in immunodeficiency, ectodermal dysplasia, and susceptibility to atypical mycobacterial infections due to impaired NF-κB activation (42). A number of these mutations affect the C-terminal domains of NEMO (42), which we demonstrate are not absolutely required for NF-κB activation by K13. Thus, K13-based gene therapy approaches may have utility for the treatment of patients with NEMO mutations and immunodeficiency.

At the time of its discovery, K13 was believed to act as an inhibitor of caspase 8/FLICE and protect cells against death receptor-induced apoptosis (10–12). Consistent with this concept, ectopic expression of K13 was shown to protect HeLa cells against Fas-induced apoptosis (43). Similarly, small interfering RNA-mediated silencing of K13 was shown to sensitize BC3 cells to Fas-induced apoptosis (20). However, since NF-κB is known to protect against death receptor-induced apoptosis by upregulating the expression of a number of antiapoptotic proteins (44), it was not clear whether the protective effect of K13 against death receptor-induced apoptosis observed in the above-described studies was due to its ability to directly inhibit caspase 8 activation or due to its activation of the NF-κB pathway. In this study, we observed that K13 fails to confer any protection against TNF-α-induced apoptosis in NEMO−/Y cells, thereby arguing against the former possibility. However, K13 was able to confer significant protection when NEMO−/Y cells were reconstituted with the NEMO(1-251) mutant, which is capable of selectively supporting K13-induced NF-κB, thereby favoring the latter possibility. These results are consistent with those of our previous study in which K13 transgenic mice failed to recapitulate the phenotype observed in caspase 8-knockout mice (19) and provide further support to the notion that K13 is primarily an activator of NF-κB rather than an inhibitor of caspase 8/FLICE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stephen Michnick for providing the hGLuc constructs and Shao-Cong Sun and Inder Verma for NEMO-deficient Jurkat and MEFs, respectively.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA139119, DE019811, and P30CA014089), the Stop Cancer Foundation, and SC CTSI (NIH/NCRR/NCATS) through grant UL1TR000130.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta SC, Sundaram C, Reuter S, Aggarwal BB. 2010. Inhibiting NF-kappaB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799:775–787. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal BB. 2004. Nuclear factor-kappaB: the enemy within. Cancer Cell 6:203–208. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richmond A. 2002. Nf-kappa B, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:664–674. 10.1038/nri887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. 2004. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 18:2195–2224. 10.1101/gad.1228704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M, Delhase M. 2000. The I kappa B kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: key elements of proinflammatory signalling. Semin. Immunol. 12:85–98. 10.1006/smim.2000.0210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karin M. 2006. Nuclear factor-[kappa]B in cancer development and progression. Nature 441:431. 10.1038/nature04870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, Moore PS. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865–1869. 10.1126/science.7997879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Dawson DB, Ansari MQ, Sald J, Knowles DM. 1996. Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood 88:645–656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, d'Agay MF, Clauvel JP, Raphael M, Degos L, Sigaux F. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood 86:1276–1280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertin J, Armstrong RC, Ottilie S, Martin DA, Wang Y, Banks S, Wang GH, Senkevich TG, Alnemri ES, Moss B, Lenardo MJ, Tomaselli KJ, Cohen JI. 1997. Death effector domain-containing herpesvirus and poxvirus proteins inhibit both Fas- and TNFR1-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:1172–1176. 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu S, Vincenz C, Buller M, Dixit VM. 1997. A novel family of viral death effector domain-containing molecules that inhibit both CD-95- and tumor necrosis factor receptor-1-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9621–9624. 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thome M, Schneider P, Hofmann K, Fickenscher H, Meinl E, Neipel F, Mattmann C, Burns K, Bodmer JL, Schroter M, Scaffidi C, Krammer PH, Peter ME, Tschopp J. 1997. Viral FLICE-inhibitory proteins (FLIPs) prevent apoptosis induced by death receptors. Nature 386:517–521. 10.1038/386517a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhary PM, Jasmin A, Eby MT, Hood L. 1999. Modulation of the NF-kappa B pathway by virally encoded death effector domains-containing proteins. Oncogene 18:5738–5746. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, Eby MT, Rathore N, Sinha SK, Kumar A, Chaudhary PM. 2002. The human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein physically associates with and persistently activates the Ikappa B kinase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 277:13745–13751. 10.1074/jbc.M110480200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Q, Matta H, Chaudhary PM. 2003. The human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein protects against growth factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis via NF-kappa B activation. Blood 101:1956–1961. 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Q, Zachariah S, Chaudhary PM. 2003. The human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE-inhibitory protein induces cellular transformation via NF-kappaB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52437–52445. 10.1074/jbc.M304199200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matta H, Chaudhary PM. 2004. Activation of alternative NF-kappa B pathway by human herpes virus 8-encoded Fas-associated death domain-like IL-1 beta-converting enzyme inhibitory protein (vFLIP). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:9399–9404. 10.1073/pnas.0308016101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Q, Matta H, Lu G, Chaudhary PM. 2006. Induction of IL-8 expression by human herpesvirus 8 encoded vFLIP K13 via NF-kappaB activation. Oncogene 25:2717–2726. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chugh P, Matta H, Schamus S, Zachariah S, Kumar A, Richardson JA, Smith AL, Chaudhary PM. 2005. Constitutive NF-kappaB activation, normal Fas-induced apoptosis, and increased incidence of lymphoma in human herpes virus 8 K13 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:12885–12890. 10.1073/pnas.0408577102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guasparri I, Keller SA, Cesarman E. 2004. KSHV vFLIP is essential for the survival of infected lymphoma cells. J. Exp. Med. 199:993–1003. 10.1084/jem.20031467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Matta H, Surabhi RM, Zhao J, Punj V, Sun Q, Schamus S, Mazzacurati L, Chaudhary PM. 2007. Induction of spindle cell morphology in human vascular endothelial cells by human herpesvirus 8-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein K13. Oncogene 26:1656–1660. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Ganem D. 2007. Induction of chemokine production by latent Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of endothelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 88:46–50. 10.1099/vir.0.82375-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossmann C, Podgrabinska S, Skobe M, Ganem D. 2006. Activation of NF-kappaB by the latent vFLIP gene of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for the spindle shape of virus-infected endothelial cells and contributes to their proinflammatory phenotype. J. Virol. 80:7179–7185. 10.1128/JVI.01603-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagneris C, Ageichik AV, Cronin N, Wallace B, Collins M, Boshoff C, Waksman G, Barrett T. 2008. Crystal structure of a vFlip-IKKgamma complex: insights into viral activation of the IKK signalosome. Mol. Cell 30:620–631. 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harhaj EW, Good L, Xiao G, Uhlik M, Cvijic ME, Rivera-Walsh I, Sun SC. 2000. Somatic mutagenesis studies of NF-kappa B signaling in human T cells: evidence for an essential role of IKK gamma in NF-kappa B activation by T-cell costimulatory signals and HTLV-I Tax protein. Oncogene 19:1448–1456. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matta H, Gopalakrishnan R, Graham C, Tolani B, Khanna A, Yi H, Suo Y, Chaudhary PM. 2012. Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein K13 activates NF-kappaB pathway independent of TRAF6, TAK1 and LUBAC. PLoS One 7:e36601. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remy I, Michnick SW. 2006. A highly sensitive protein-protein interaction assay based on Gaussia luciferase. Nat. Methods 3:977–979. 10.1038/nmeth979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remy I, Michnick SW. 2004. Mapping biochemical networks with protein-fragment complementation assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 261:411–426. 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matta H, Sun Q, Moses G, Chaudhary PM. 2003. Molecular genetic analysis of human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein-induced NF-kappaB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52406–52411. 10.1074/jbc.M307308200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao J, Punj V, Matta H, Mazzacurati L, Schamus S, Yang Y, Yang T, Hong Y, Chaudhary PM. 2007. K13 blocks KSHV lytic replication and deregulates vIL6 and hIL6 expression: a model of lytic replication induced clonal selection in viral oncogenesis. PLoS One 2:e1067. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alkharsah KR, Singh VV, Bosco R, Santag S, Grundhoff A, Konrad A, Sturzl M, Wirth D, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Schulz TF. 2011. Deletion of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus FLICE inhibitory protein, vFLIP, from the viral genome compromises the activation of STAT1-responsive cellular genes and spindle cell formation in endothelial cells. J. Virol. 85:10375–10388. 10.1128/JVI.00226-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudolph D, Yeh WC, Wakeham A, Rudolph B, Nallainathan D, Potter J, Elia AJ, Mak TW. 2000. Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-kappaB activation in NEMO/IKKgamma-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 14:854–862. 10.1101/gad.14.7.854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Punj V, Matta H, Schamus S, Chaudhary PM. 2009. Integrated microarray and multiplex cytokine analyses of Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus viral FLICE inhibitory protein K13 affected genes and cytokines in human blood vascular endothelial cells. BMC Med. Genomics 2:50. 10.1186/1755-8794-2-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Punj V, Matta H, Chaudhary PM. 2012. A computational profiling of changes in gene expression and transcription factors induced by vFLIP K13 in primary effusion lymphoma. PLoS One 7:e37498. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keller SA, Hernandez-Hopkins D, Vider J, Ponomarev V, Hyjek E, Schattner EJ, Cesarman E. 2006. NF-{kappa}B is essential for progression of KSHV- and EBV-infected lymphomas in vivo. Blood 107:3295–3302. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris K. 2003. Cancer? In Africa? Lancet Oncol. 4:5. 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)00969-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wabinga HR, Parkin DM, Wabwire-Mangen F, Mugerwa JW. 1993. Cancer in Kampala, Uganda, in 1989-91: changes in incidence in the era of AIDS. Int. J. Cancer 54:26–36. 10.1002/ijc.2910540106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sturzl M, Hohenadl C, Zietz C, Castanos-Velez E, Wunderlich A, Ascherl G, Biberfeld P, Monini P, Browning PJ, Ensoli B. 1999. Expression of K13/v-FLIP gene of human herpesvirus 8 and apoptosis in Kaposi's sarcoma spindle cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91:1725–1733. 10.1093/jnci/91.20.1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarid R, Flore O, Bohenzky RA, Chang Y, Moore PS. 1998. Transcription mapping of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genome in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BC-1). J. Virol. 72:1005–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao T, Yang L, Sun Q, Arguello M, Ballard DW, Hiscott J, Lin R. 2007. The NEMO adaptor bridges the nuclear factor-kappaB and interferon regulatory factor signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 8:592–600. 10.1038/ni1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Israel A. 2010. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000158. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Courtois G, Smahi A. 2006. NF-kappaB-related genetic diseases. Cell Death Differ. 13:843–851. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belanger C, Gravel A, Tomoiu A, Janelle ME, Gosselin J, Tremblay MJ, Flamand L. 2001. Human herpesvirus 8 viral FLICE-inhibitory protein inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis through binding and prevention of procaspase-8 maturation. J. Hum. Virol. 4:62–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aggarwal BB. 2000. Apoptosis and nuclear factor-kappa B: a tale of association and dissociation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 60:1033–1039. 10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00393-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]