Abstract

Aims

To measure the impact of newspaper advertising across Scotland on patient interest, and subsequent recruitment into the Standard Care vs. Celecoxib Outcome Trial (SCOT), a clinical trial investigating the cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

Newspaper advertisements about the SCOT trial were placed sequentially in regional and national Scottish newspapers. The number of phone calls as a result of exposure to the advertisements and ongoing study recruitment rates were recorded before, during and after the advertising campaign. To enroll in SCOT individuals had to be registered with a participating GP practice.

Results

The total cost for the advertising campaign was £46 250 and 320 phone calls were received as a result of individuals responding to the newspaper advertisements. One hundred and seventy-two individuals were identified as possibly suitable to be included in the study. However only 36 were registered at participating GP practices, 17 completed a screening visit and 15 finally were randomized into the study. The average cost per respondent individual was £144 and the average cost per randomized patient was £3083. Analysis of recruitment rate trends showed that there was no impact of the newspaper advertising campaign on increasing recruitment into SCOT.

Conclusions

Advertisements placed in local and national newspapers were not an effective recruitment strategy for the SCOT trial. The advertisements attracted relatively small numbers of respondents, many of whom did not meet study inclusion criteria or were not registered at a participating GP practice.

Keywords: clinical trials, newspaper advertising, recruitment

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Patient recruitment into clinical trials involves considerable cost and effort. Paid media advertising campaigns are a potentially important tool in recruiting patients to clinical trials but evidence regarding their effectiveness is lacking.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In Scotland a local and national newspaper advertising campaign was an ineffective method of recruiting subjects into a particular clinical trial.

Introduction

Recruitment of participants is arguably the most important, most difficult and least predictable aspect of clinical trials. If recruitment has to be extended to reach the required sample size then this can delay the results and increase the trial costs 1. There are multiple strategies that might be employed to improve recruitment including all forms of media advertising, GP database searches, referrals from secondary care and directly writing to patients 2–9. However robust evidence supporting the efficacy of any of these recruitment strategies is lacking 10. One of the main limiting factors in subject recruitment is patient willingness to participate which may be due to a lack of information about the study or clinical trial benefits 11, fear of being treated like a ‘guinea pig’ and concerns about how much time and effort would be required on their part. There can also be reluctance on the part of physicians to refer patients into clinical trials 12,13, possibly again due to lack of information or concerns about increasing their workload. Promoting awareness and raising public interest in clinical trials can potentially be achieved using newspaper advertisements 7,11,14 and the aim of this study was to assess the impact of a newspaper advertising campaign on patient interest and recruitment rates in the Standard care vs. Celecoxib Outcome Trial (SCOT) (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00447759) 15.

Methods

SCOT overview

SCOT is a large streamlined safety study designed to compare the cardiovascular safety of celecoxib vs. traditional non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy (multicentre research ethics (MREC) approval number: 07/MREOO/9). The SCOT trial is running in the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands but this paper concerns advertisements confined to four study centres in Scotland.

The usual method of recruiting patients to SCOT in Scotland involves GP practices agreeing to participate in the trial, potentially suitable patients being identified from the GP practice and invited to participate. Suitable patients are those over the age of 60 years who take regular NSAIDs for osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Patients who respond to the initial communication are then contacted by a study nurse to determine suitability to enter the study. Recruitment rates are recorded on a weekly basis and, as an example, for the GP practices in Dundee, on average 15% of invited patients eventually randomize into the study.

Study design

The advertising campaign was designed to have regional or national impact. Newspaper advertisements about SCOT were placed sequentially in five regional and four national newspapers in Scotland. An example of one of the advertisements used is shown in Figure 1. The size of the advertisement depended on the publication but covered approximately a quarter of a page and all advertisements were in colour. The advertisement targeted patients with arthritis by showing a picture of an arthritic hand and gave brief information about the SCOT study with a freephone contact number and website address. The local advertisements lasted for 1 week in each of the regional newspapers between 6 July 2009 and 22 August 2009. The targeted regions across Scotland were Grampian (Aberdeen and surrounding area), Tayside/Fife (Dundee and surrounding area), Lothian (Edinburgh and surrounding area) and Greater Glasgow.

Figure 1.

Example of a SCOT newspaper advertisement

The national campaigns were designed to have different advertising intensities. During the first national campaign the advertisement was published for a week in October 2009 (week commencing 19 October 2009 (Monday–Saturday)). Six months later the advertisement was run for another 3 weeks intermittently between 15 February and 21 March 2010. The advertisements and advertising campaign were devised initially in collaboration with a professional public relations company (Beattie Communications)1.

In general, the newspapers selected had wide coverage locally or nationally across Scotland, with a total daily circulation in 2009/2010 of 574 281. The total cost of the advertisement campaign was £46 250. Details of the newspapers selected and advertising dates are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of advertising campaign

| Date | Paper | Daily circulation | Area | Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/c 06/07/2009 (Mon–Sat) | Scotsman | 47 898 | Regional/Edinburgh | £10 433 |

| w/c 20/07/2009 (Mon–Sat) | P&J | 81 956 | Regional/Aberdeen | £5748 |

| w/c 03/08/2009 (Mon–Sat) | The Herald | 73 485 | Regional/Glasgow | £5731 |

| w/c 17/08/2009 (Mon–Sat) | Dundee Courier | 60 605 | Regional/Dundee | £9562 |

| w/c 19/10/2009 (Mon–Sat) | Scottish Daily Mail | 11 5318 | National | £796* |

| w/c 15/02/2010 (Mon–Sat) | Scottish Daily Express | 68 668 | National | £5020 |

| w/c 01/03/2010 (Mon–Sat) | Times Scotland | 23 555 | National | £3960 |

| w/c 15/03/2010 (Mon–Sat) | Daily Record | 102 796 | National | £5000 |

| Total | 574 281 | £46 250 |

This was a special package (reduced rate).

The impact of the advertising campaign was assessed firstly by recording the number of phone calls made by interested members of the public to the free-phone telephone line to obtain further information about SCOT and secondly by analyzing changes in recruitment trends as a result of positive responses to the invitation letters sent to potentially suitable patients. Activity on the SCOT website was also monitored. Subjects with participating GPs who were potentially suitable for inclusion in the study were followed up by SCOT study nurses. For subjects whose GPs were not already participating in SCOT, study nurses contacted their GP to try to recruit more practices to SCOT.

Weekly study recruitment rates were logged for each of the centres in Aberdeen (Grampian), Dundee (Tayside), Edinburgh (Lothian), and Glasgow (Greater Glasgow region). Data collection spanned from 16 of February 2008 to 21 January 2012.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis focused on two aspects of the study design outcome: (1) the number of members of the public calling the freephone line as a result of seeing the advertisement and (2) the impact of advertising campaigns on SCOT recruitment rates.

The number of patients calling the free-phone line was assessed using descriptive data analysis. The impact on recruitment rates was assessed using an Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving-Average (ARIMA 16) modelling approach for interrupted time series. This analysis allowed us to identify statistically significant changes in recruitment rates, as well as the type of change (short or long duration).

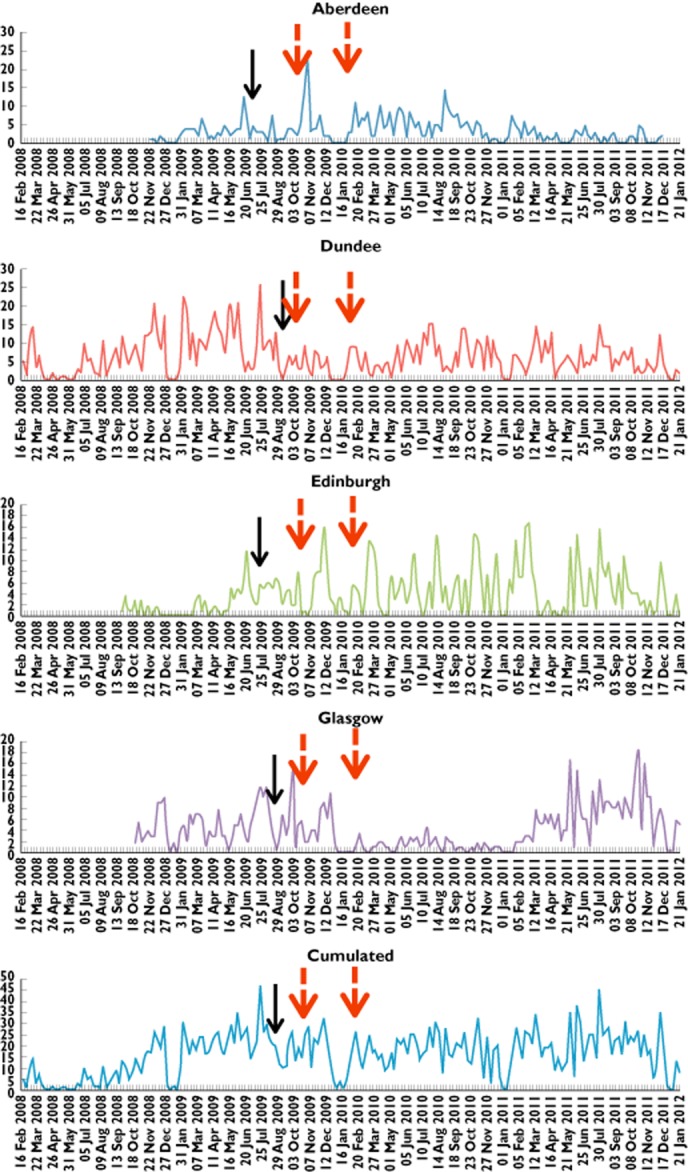

For statistical analysis purposes, recruitment rate records for each region were divided into four periods. To control for possible confounding factors such as seasonality, only 30 weeks of recruitment data prior to first advertisement, the recruitment data between advertisements and 30 weeks of recruitment data after the last advertisement were retained in the analysis. The four periods used were: period 1: 30 weeks of recruitment prior to the first local advertisement, period 2: local advertisement to first national advertisement, period 3: first national advertisement to second national advertisement and period 4: second national advertisement to 30 weeks after the last advertisement. Figure 2 shows the recruitment rates across the four regions, cumulative rates and the timing of the different local and regional advertisements. The ARIMA model parameters were selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) together with the assessment of the autocorrelation and partial correlation function 16.

Figure 2.

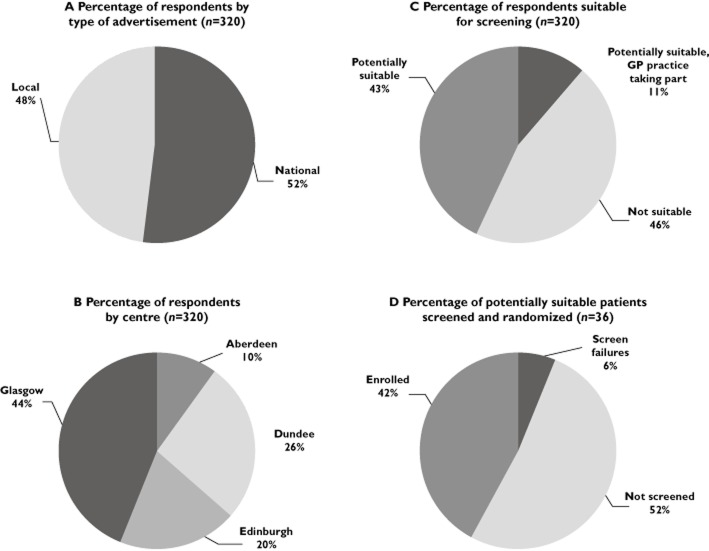

Location and outcomes for respondents to newspaper advertisements. (A) percentage of respondents by type of advertisement, (B) percentage of respondents by centre, (C) percentage of respondents suitable for screening and (D) percentage of potentially suitable patients screened and randomized

Data analysis was performed using SAS v.9.3 software.

The efficiency and cost effectiveness of the advertising campaign was assessed by calculating the cost–time index (CTI) 17 and this is shown in Table 3. The CTI simultaneously measures the cost and time efficiency of a particular recruitment method, in this case a newspaper advertisement and reflects the expenditure in terms of both money and time required by a clinical trial to recruit one patient. CTI is calculated by:

Table 3.

Cost analysis and cost time index

| Cost per respondent | Cost per suitable patient | Cost–time calculation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional | £207 | £338 | £1242 |

| National 1 | £18 | £33 | £109 |

| National 2 | £113 | £254 | £2029 |

| Total | £145 | £269 | NA |

(TC = total cost for a given advertisement, Z = the number of days the advertisement was published in a week, W = the number of weeks the advertisement was run, S = the number of subjects who were considered suitable recruited from each advertisement).

A low figure for CTI is desirable as this corresponds with more efficient recruitment. However, this figure needs to be interpreted carefully as time constraints on a particular trial may make higher costs acceptable to recruit patients in a shorter time. Costs included were the direct costs of the advertisements and did not take into account the costs of advertisement design, phone calls or staff costs.

Results

Number of telephone calls as a result of advertising campaign

The number of telephone calls recorded in response to the advertising campaigns is presented in Table 2. On average there were 40 respondents for each week of advertising.

Table 2.

Number of phone calls and number of potentially suitable respondents by region and type of advertisement

| Region | Regional advert | National advert 1 | National advert 2 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calls | Suitable patients | Calls | Suitable patients | Calls | Suitable patients | Calls | Suitable patients | |

| Aberdeen | 22 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 32 | 17 |

| Dundee | 53 | 33 | 14 | 7 | 17 | 9 | 84 | 49 |

| Edinburgh | 28 | 21 | 8 | 6 | 27 | 14 | 63 | 41 |

| Glasgow | 49 | 26 | 18 | 9 | 74 | 30 | 141 | 65 |

| Total | 152 | 93 | 44 | 24 | 124 | 55 | 320 | 172 |

A total of 320 people responded to the advertisements by phoning the SCOT phone line. Forty-eight % (n = 152) responded to the advertisement in local newspapers and 52% (n = 168) to the advertisement in national newspapers (Figure 2A). The proportions of people responding from different areas were 10% from Aberdeen (Grampian), 26% from Dundee (Tayside), 20% from Edinburgh (Lothian) and 44% from Glasgow (Greater Glasgow region) (Figure 2B). Over the advertising period the number of hits on the SCOT website did not change in relation to the timing of the newspaper advertisements.

Of all the respondents, 54% (n = 172) were judged as potentially suitable by the study research nurse at the time of the initial phone call and of the potentially suitable patients 21 % (n = 36) were registered at a GP practice taking part in the SCOT study (Figure 2C). Of those who were suitable and whose GP practice was taking part in the study (n = 36), 48% (n = 17) were screened, leading to 42% (n = 15) enrolled into the study (Figure 2D). This equates to a disappointingly low conversion rate from making contact to study enrolment of 4.7% (15 enrolled from 320 respondents).

The impact of the advertising campaign on study recruitment rates

The average recruitment rates per region over the four periods delineated by the advertisements are presented in Figure 3. There was no consistent response pattern for recruitment rates as a result of the advertising campaigns. The recruitment rate average in Dundee decreased after the local and first national advertisement and increased after the second national advertisement, whilst in Aberdeen the recruitment rate increased after the first two advertisements and decreased after the last one.

Figure 3.

Changes in recruitment rates by region in response to regional and national advertisements. ( ) National advert and (

) National advert and ( ) Regional advert

) Regional advert

The ARIMA modelling approach was applied to each set of recruitment rate data including the cumulative figures. The model output shows that the only significant impact on recruitment rates (P = 0.04) was recorded in the Dundee region after the local newspaper advertising campaign. The impact was gradual (P < 0.001), however both the intervention model coefficients were negative suggesting a negative impact, i.e. a reduction in recruitment rate following advertising. For the other three regions and the cumulated recruitment figures, the analysis of the recruitment rates did not show any impact of the advertisements.

The average cost per responding patient by newspaper type showed that the 1 week advertising campaign in a national newspaper was the most economical at £18 per respondent, whilst advertisements in local papers were the most expensive at £207 per respondent (although this result was potentially biased by the fact that the price obtained for that particular advertising week in a national paper was promotional). The CTI (Table 3) shows that the most cost-effective campaign was the 1 week of national advertising (£109 per day per respondent) while the least cost-effective was the 3 weeks national advertising campaign (£2029 per day per respondent). Regardless of the costs and type of newspaper, the number of individuals responding to advertisements was proportional to the number of weeks that the advertisement was run and averaged around 40 calls per week of advertising.

The average cost per responding patient was £145 and the average cost per potentially suitable patient was £269. The overall cost per randomized patient was £3083. The largest loss of potential participants was due to non-participation of the GP practice. Figure 2D shows that 48% of patients with participating GPs were screened and the screening to randomization conversion rate was 88%. Therefore if all potentially suitable patients (n = 172) had a participating GP we could have expected conservatively to recruit 73 patients improving study enrolment from 4.7% to 23%. This would have brought costs down from £3083 to £633 per randomized patient.

Discussion

Advertising campaigns have been reported as successful and cost-effective ways of increasing public awareness and willingness to participate in clinical research 11. How advertising is used to recruit for a particular clinical trial will depend on the trial design and the type of subject required. SCOT required recruitment of patients over the age of 60 years, who were prescribed an NSAID long term for either osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. With the high prevalence of these conditions in the population it was felt that a newspaper advertising campaign with a daily circulation reaching over 570 000 people would be an effective recruitment method. However, in this study £46 250 was spent on an advertising campaign that generated 320 phone calls, with only 172 people being judged as potentially suitable to participate in the trial leading to a cost of £269 per potentially suitable subject. Disappointingly, after screening, only 15 patients (4.7% of respondents) met the study entry criteria, making the average cost per randomized patient £3083.

One of the main concerns with newspaper advertising is the heterogeneous nature of the audience covered and the difficulty in targeting those who are likely to meet the entry criteria. In the example of SCOT, potential subjects had to be over 60 years and prescribed a regular NSAID. However there were a number of exclusion criteria including pre-existing cardiovascular disease, active peptic ulceration, allergies to trial medication and other significant co-morbidities. Information about exclusion criteria was not included in the advertisements published and therefore of the 320 initial phone calls, 148 were not suitable from the first contact made.

Patients also had to be registered at a participating GP practice and this was the most significant barrier to recruitment of potentially suitable individuals. Only 36 (21%) of the 172 potentially suitable patients were registered at participating practices. Of the 36 patients who were registered with a participating GP less than half (48%) were actually screened. After initial telephone response to the advertisement potentially suitable patients were followed up by SCOT study nurses who contacted the patient's GP to confirm eligibility and arrange screening. A number of patients were found to be unsuitable for the trial at this stage. We also tried to engage more GP practices in the study by contacting them when one of their patients expressed an interest in the trial. However, no additional practices participated following such contacts. The dependence on GP ‘buy-in’ undoubtedly deprives clinical trials of potential subjects but also deprives patients of access to participation in clinical research. The geographical location of potential subjects, especially those based in more remote regions of Scotland was also a potential barrier to recruitment as the more rural GP practices were less likely to be participating in the study mainly for logistical reasons beyond their control.

In other studies newspaper advertising was found to be the most cost-effective recruitment method when compared with alternatives including newsletters, posters, radio advertising, approaches to community groups, approaches via general practices and an electoral roll mail-out 7,8. However, in these studies the success of newspaper advertising was significantly influenced by the type of newspaper, for example free local papers with high distribution and relatively cheap advertising vs. more expensive advertising in national newspapers. Also the study entry criteria were broad, there were few exclusion criteria and the studies were ‘attractive’ to potential participants with a low risk intervention for conditions with a high symptom burden. Response to newspaper advertising can be unpredictable, for example, the VECAT (Vitamin E Intervention in Cataract and Age related Maculopathy) study 7 found that their newspaper advertising campaign generated very high initial interest which overwhelmed the ability of the study nurses to deal with the phone calls generated but this interest rapidly decreased leading to an unpredictable workload. Another Australian study looking at recruitment of older adults into a trial comparing geriatric assessment and primary care physician management 9 used various recruitment methods including direct referrals, presentations and media including fliers and mailings and found that the most efficient recruitment method was direct referrals. However, this method did not recruit enough participants to power the study and therefore more expensive methods including media advertising were required to complete recruitment in time. This highlights the complexity of recruitment into clinical trials and that both cost and time efficiency are crucial factors. Research into clinical trial recruitment often occurs as a nested trial within a main trial and while this is likely the most efficient and effective method of collecting data in this area it can present challenges to the research team balancing the requirements of both trials 18.

The effectiveness of newspaper advertising itself is widely discussed in marketing literature and the evidence shows that the impact of newspaper advertising is complex and dependent on a hierarchy of factors 19. The first of these factors is the input i.e. the message content, the media source and the schedule by which it is delivered. The advertisements used in this study were carefully designed with initial input from a professional public relations company2 and the size, colour, picture and simple wording were chosen in an attempt to attract the target audience. The freephone telephone number and website address aimed to make contact for further information as straightforward as possible. The media source chosen was local and national newspapers with large distribution areas and both daily and weekly advertisements were run. Feedback from the public with regard to their response to advertising for clinical trial recruitment is largely anecdotal and ethically it is not possible to obtain feedback from those who decided they were not interested. It is therefore difficult to know what advertising is likely to be most effective and again this will depend on the type of trial and the target audience. We did not collect feedback from patients who responded to the advertisements to establish what had prompted them to make contact. However, generally, it is agreed that the public are more likely to enrol in trials where they are directly affected by the condition in question, enrolment in the trial is unlikely to adversely impact their health, e.g. likelihood of significant side effects from trial medication and the perceived costs in terms of time and resources (travel etc.) are reasonable 2.

While it may appear initially that the newspaper advertising campaign for SCOT was extremely expensive for limited gain costing £3083 to recruit one patient, it is important to consider the general current difficulties in recruiting patients to clinical trials. Other investigators have reported similar costs per respondent using advertising campaigns for recruitment 4 and in some cases this is deemed cost-effective particularly when recruitment in a timely manner is key to the success of the trial. In less well funded trials which require large numbers of participants this cost is not sustainable and the price per recruited subject can easily rise under particularly stringent study entry criteria. Prior to the newspaper advertising campaign recruitment into SCOT was achieved by searching GP databases for potential patients and then inviting them to participate. Using the Dundee GPs as an example, on average 2% of patients registered with each GP (approximately 90 patients) were considered potentially suitable and invited to participate. Of those 22% responded to the initial letter resulting in 15% of those invited finally being randomized into the trial i.e. on average 14 patients per GP practice were finally randomized. Therefore it may be considered that generating 320 phone calls was a good result for the investment in the newspaper advertising campaign. However this did not translate into randomized patients due to the logistics of SCOT.

In conclusion, we found that the use of newspaper advertising as a tool to enhance recruitment into SCOT was costly and ineffective. The use of a targeted newspaper advertising campaign may have a role in recruitment to other studies with broader entry criteria and no requirement for prior GP participation but would need to be carefully planned and researched. Overall, other ways of engaging the public in clinical research need to be developed. For example the ‘Get randomised’ campaign 11 improved public awareness of clinical trials but concluded that further work was needed to translate this increased awareness into increased willingness to participate.

Footnotes

Beattie Communications (Integrated Public Relations, Web Marketing and Social Media Agency).

See footnote 1.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: The SCOT trial received funding from Pfizer and is sponsored by the University of Dundee. TMM holds research grants from Novartis, Pfizer, Ipsen & Menarini, is currently or has been the principal investigator on trials paid for by Pfizer, Novartis, Ipsen & Menarini and TMM has been paid consulting or speakers fees by Pfizer, Novartis, Kaiser Permanante, Takeda, Recordati, Servier, Menarini and AstraZeneca in the previous 3 years. IM holds research grants from Novartis, Ipsen & Menarini. There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D, Elbourne D, McDonald AM, Knight R, Entwhistle V, Garcia J, Roberts I, Grant A. Recruitment to randomised trials: strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:1–140. doi: 10.3310/hta11480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treweek S, Pitkethly M, Cook J, Kjeldstrom M, Taskila T, Johansen M, Sullivan F, Wilson S, Jackson C, Jones R, Mitchell E. Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub5. MR000013. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Probstfield J, Frye R. Strategies for recruitment and retention of participants in clinical trials. JAMA. 2011;306:1798–1799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinshaw L, Jackson S, Chen M. Direct mailing was a successful recruitment strategy for a lung-cancer screening trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:853–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham A, Milner P, Saul J, Pfaff L. Online advertising as a public health and recruitment tool: comparison of different media campaigns to increase demand for smoking cessation interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cambron J, Dexheimer J, Chang M, Cramer G. Recruitment methods and costs for a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of chiropractic care for lumbar spinal stenosis: a single-site pilot study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrett SK, Thomas AP, Cicuttini F, Silagy C, Taylor HR, McNeil JJ. Community-based recruitment strategies for a longitudinal interventional study: the VECAT experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:541–548. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butt DA, Lock M, Harvey BJ. Effective and cost-effective clinical trial recruitment strategies for postmenopausal women in a community-based, primary care setting. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams J, Silverman M, Musa D, Peele P. Recruiting older adults for clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1997;18:14–26. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson JM, Torgerson DJ. Increasing recruitment to randomised trials: a review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie I, Wei L, Rutherford D, Findlay E, Saywood W, Campbell MK, Macdonald T. Promoting public awareness of randomised clinical trials using the media: the ‘Get Randomised’ campaign. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:128–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross S, Grant A, Counsell C, Gillespie W, Russell I, Prescott R. Barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1143–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewison J, Haines A. Overcoming barriers to recruitment in health research. BMJ. 2006;333:300–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7562.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey R, Edwards S, Cochrane T. Recruitment strategies for a clinical trial of community-based water therapy for osteoarthritis. Br J. Gen Pract. 2003;53:315–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonald TM, Mackenzie IS, Wei L, Hawkey C, Ford I. SCOT study group collaborators. Methodology of a large prospective, randomised, open, blinded endpoint streamlined safety study of celecoxib versus traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis: protocol of the standard care versus celecoxib outcome trial (SCOT) BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002295. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDowall D, McCleary R, Meidlinger E, Hay RA. Interrupted Time Series Analysis. 6th edn. University of California: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ota KS, Friedman L, Ashford JW, Hernandez B, Penner AL, Stepp AM, Raam R, Yesavage JA. The Cost-Time Index: a new method for measuring the efficiencies of recruitment-resources in clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27:494–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graffy J, Bower P, Ward E, Wallace P, Delaney B, Kinmonth AL, Collier D, Miller J. Trials within trials? Researcher, funder and ethical perspectives on the practicality and acceptability of nesting trials of recruitment methods in existing primary care trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vakratsas D, Ambler T. How advertising works: what do we really know. J Mark. 1999;63:26–43. [Google Scholar]