Abstract

Mortalin, a member of the Hsp70-family of molecular chaperones, functions in a variety of processes including mitochondrial protein import and quality control, Fe-S cluster protein biogenesis, mitochondrial homeostasis, and regulation of p53. Mortalin is implicated in regulation of apoptosis, cell stress response, neurodegeneration, and cancer and is a target of the antitumor compound MKT-077. Like other Hsp70-family members, Mortalin consists of a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a substrate-binding domain. We determined the crystal structure of the NBD of human Mortalin at 2.8 Å resolution. Although the Mortalin nucleotide-binding pocket is highly conserved relative to other Hsp70 family members, we find that its nucleotide affinity is weaker than that of Hsc70. A Parkinson's disease-associated mutation is located on the Mortalin-NBD surface and may contribute to Mortalin aggregation. We present structure-based models for how the Mortalin-NBD may interact with the nucleotide exchange factor GrpEL1, with p53, and with MKT-077. Our structure may contribute to the understanding of disease-associated Mortalin mutations and to improved Mortalin-targeting antitumor compounds.

Keywords: mitochondria, protein quality control, Heat-shock protein 70, p53, chaperone inhibitor, nucleotide binding

Introduction

The Hsp70 chaperone family plays key roles in cellular homeostasis and stress response. Hsp70-family members not only regulate folding of nascent proteins but also prevent protein aggregation, promote disaggregation, and refold misfolded proteins. Hsp70-family members participate in additional cellular processes including conformational control of regulatory proteins, intracellular trafficking, uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles, and protein translocation across intracellular membranes.1,2 In eukaryotes, family members localize to the cytosol (Hsp70, Hsc70 and close homologues), the endoplasmic reticulum (BiP/Grp78), and mitochondria (Mortalin).

Mortalin, also known as mtHsp70, HSPA9/HSPA9B or Grp75, was identified in mice as a cellular mortality factor3 and determined to be an Hsp70-family member primarily localized to mitochondria.4 Its sequence is slightly more homologous to those of the Escherichia coli Hsp70 chaperones DnaK and HscA than to other mammalian Hsp70-family members, suggesting that it may descend from a DnaK-like chaperone of an endosymbiont precursor of mitochondria. Mortalin regulates protein folding and quality control in the mitochondrial matrix,5 as well as iron-sulfur cluster-biogenesis and insertion into Fe-S apoproteins.6 Mortalin participates directly in mitochondrial protein import through the TIM (translocase of the inner membrane) protein complex.7,8 Mortalin also cooperates with mitochondrial homeostasis factors including TRAP-1 and the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC),9 and regulates mitochondrial properties including ATP levels, membrane potential and permeability, and response to reactive oxygen species.10,11

Interestingly, a fraction of Mortalin localizes to the cytosol where it associates with proteins involved in signaling, apoptosis, or senescence. Significantly, Mortalin binds to cytoplasmic p53 and negatively regulates this crucial tumor suppressor, especially under modest stresses.12,13 Mortalin levels and Mortalin-p53 association are increased in cancer cell lines and tumor models.14–16 Mortalin prevents nuclear translocation of p5317 and also blocks p53-mediated suppression of centrosome duplication.18

As it acts on a variety of binding partners and is important for mitochondrial homeostasis, Mortalin is of interest as a therapeutic target in a number of pathologies. In particular, Mortalin may play a general antiapoptotic role in cancers. Elevated levels of Mortalin are present in individuals with chronic myelogenous leukemia, colerectal adenocarcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma as well as in several tumor cell lines.19,20 Mortalin function and levels are also altered in several neurodegenerative diseases characterized by neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases.11,21 Such findings have driven efforts to modulate Mortalin function using small-molecule- or RNA silencing-based therapeutic approaches.22,23 MKT-077, a rhodacyanine dye, was characterized as an inducer of mitochondrial toxicity with antitumor activity well before Mortalin was identified as one of its targets. MKT-077 induces senescence in cancer cell lines,24 attenuates Mortalin's inhibition of p53,16,25 and may also sensitize cancer cells to destruction by complement in a Mortalin-dependent fashion.26 Although Phase I clinical trials of MKT-077 against advanced solid tumors were halted due to excessive renal toxicity,27,28 this compound continues to hold interest as a starting point for inhibitors of Mortalin and other Hsp70-family members.

Like other Hsp70-family members, Mortalin consists of a ∼42 kD NBD and a ∼25 kD substrate-binding domain (SBD). The SBD itself is divided into a β-sandwich domain (SBDβ) and a ∼12 kD α-helical “lid” domain (SBDα). SBDβ contains the substrate binding site with specificity for mixed basic-hydrophobic sequences. SBDα consists of five helices and covers the peptide binding site in the high-substrate-affinity ADP-bound conformation of Hsp70-family members. In this configuration, the NBD and SBD do not interact with each other but are tethered by a short interdomain linker. On ADP-ATP exchange, the SBDα undergoes a large conformational change and reorientation, leaving the peptide binding site open. This conformational change is accompanied by docking of the interdomain linker and the SBDβ to the NBD, as well as conformational change in the SBDβ, promoting substrate protein release. Together, these mechanisms underlie nucleotide-dependent allosteric regulation of the activity of Hsp70-family members.29

Although a crystal structure of the Mortalin SBDβ with the first two helices of the SBDα was recently solved (PDB ID 3N8E), no structural data on the Mortalin NBD has been available. The NBD is a potential target for nucleotide-competitive inhibitors as well as potentially allosteric inhibitors such as MKT-077.30 Elucidation of the NBD structure may aid development of more specific and effective mortalin-targeting compounds and is necessary to understand the functional mechanisms of the full-length protein. In this study, we present the crystal structure of the NBD of human mortalin at 2.8-Å resolution. We investigate how several residues in the nucleotide-binding pocket that are not conserved in other mammalian Hsp70-family members affect nucleotide binding. We also model the interaction of the Mortalin-NBD with its nucleotide exchange factor mtGrpEL1 and with a potential Mortalin-binding site of p53. Finally, we suggest how MKT-077 may bind to the NBD to inhibit Mortalin function.

Results and Discussion

Structure of the Mortalin-NBD

We crystallized and solved the structure of the apo-(NBD of human mortalin to 2.8 Å resolution by molecular replacement, using the NBD of human Hsp70 (PDB ID 3ATU) as a search model.31 Data processing and refinement statistics are shown in Table I. The crystallized protein construct includes Residues 52–431, containing the entire globular NBD but not the N-terminal mitochondrial import sequence (Residues 1–46) or the NBD-SBD interdomain linker (Residues 432–441). As in other Hsp70 chaperones, the mortalin NBD is subdivided into four subdomains [IA, IB, IIA, and IIB, shown in Fig. 1(A)], with the nucleotide-binding pocket located at the center of the domain. Residues 54–429 are resolved fully with the exception of Residues 335–337, which form the tip of a hairpin loop in subdomain IIB.

Table I.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Data collection (Beamline ALS 4.2.2) | |

|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.00 |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell | |

| Lengths (Å) | a = 51.20, b = 67.81, c = 120.77 |

| Angles (°) | α= β = γ = 90° |

| Resolution (Å)a | 60.38–2.80 (2.90–2.80) |

| Total/unique reflections | 10669/1052 |

| Completeness (%)a | 98.0 (96.2) |

| <I/σI>a | 22.6 (4.3) |

| Rmergea,b | 0.091 (0.383) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 60.38–2.80 |

| No. of reflections | 10008 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.218/0.271 |

| No. of atoms/average B-factor (Å2) | 2787 (37.9) |

| Protein | 2779 (38.0) |

| Nonprotein | 8 (30.6) |

| R.m.s. deviation bonds (Å) | 0.013 |

| R.m.s. deviation angles (°) | 0.86 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | |

| Favored | 96.5 |

| Allowed | 100.0 |

| Disallowed | 0.0 |

| MolProbity validation: | |

| Clash score/percentile | 22.7 (85th percentile, N = 141, 2.8 ± 0.25 Å) |

| MolProbity score/percentile | 2.08 (99th percentile, N = 4482, 2.8 ± 0.25 Å) |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Merging R factor is defined as

Figure 1.

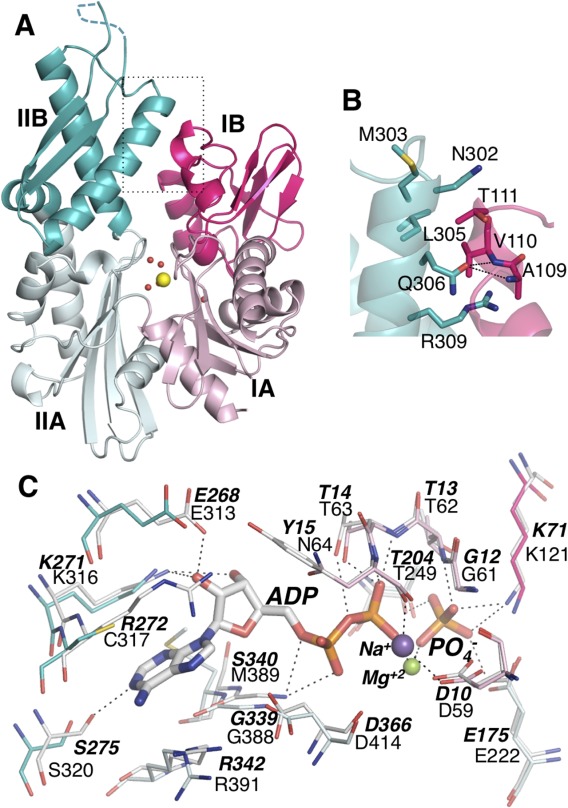

(A) Overall structure of the NBD of human Mortalin. The four distinct subdomains are labeled and individually colored. The dashed segment represents a short loop that was not resolved in the electron density map. Waters and a sodium ion in the nucleotide-binding pocket are shown as red and yellow spheres, respectively. The dotted box marks the region shown in panel (B). (B) Closeup view of packing interactions between subdomains IB and IIB at the top of the interdomain cleft. Dashed lines indicate putative hydrogen bonds. The secondary structure cartoon is rendered transparent for clarity. (C) Comparison of the nucleotide-binding pocket of Mortalin with that of the Hsp70-NBD with ADP-Pi (PDB ID 3ATU).31 Mortalin residues are colored as in panel (A), while Hsp70 residues are colored with white carbons. Hsp70 residues are labeled in bold italics while plain labels designate the Mortalin counterparts. In this representation, the rotamers of several Mortalin residues have been adjusted (from their orientations in the nucleotide-free crystal structure) to match the corresponding Hsp70 residues. Use this link to access the interactive version of this figure.

NBD structures are characterized by conformational flexibility and variable orientations of the subdomains relative to each other, depending on nucleotide occupancy and binding to cochaperone proteins.29 Based on a DALI database search,32 our Mortalin NBD structure most closely resembles Hsp70-, Hsc70-, and Grp78-NBD structures bound to ATP or ADP-Pi (backbone Rmsd < 1.4 Å over 370 residues). These structures all exhibit a “closed” conformation in which subdomains IB and IIB contact each other. Closed conformations are typically stabilized by ATP or ADP-Pi, which bridge loops from all four subdomains. However, our Mortalin-NBD construct was purified in a nucleotide-free form; water molecules and a sodium ion occupy the nucleotide-binding pocket. The closed conformation of the Mortalin-NBD is likely induced by extensive crystal packing and by the water and ion network, which bridges subdomains IA and IIA. In addition, a salt bridge between K106 and E313 above the nucleotide-binding pocket bridges the cleft between subdomains IB and IIB. A similar salt bridge is observed in closed conformations of other Hsp70-family NBDs.33

Interactions at the top of the cleft between subdomains IB and IIB also stabilize the closed conformation [Fig. 1(B)]. Aliphatic portions of the V110 and T111 sidechains on subdomain IB interact with M303, L305, and aliphatic portions of N302, Q306, and R309. The Q306 sidechain interacts with opposing backbone amides and stabilizes a helical turn in subdomain IB that orients V110 and T111. These complementary regions are less conserved relative to other eukaryotic Hsp70-family members and the interactions are more extensive than in other closed structures of eukaryotic Hsp70-family NBDs. They instead resemble the equivalent regions of bacterial Hsp70s (DnaK). The extensive nature of the interactions between subdomains IA and IIA may affect the dynamics of opening and closing of the NBD and the intrinsic rate of nucleotide dissociation, which is 1–2 orders of magnitude less for E. coli DnaK than for eukaryotic Hsc70.34

Interactions of Mortalin-NBD with nucleotides

The nucleotide-binding pocket is largely conserved between Mortalin and other Hsp70-family members, allowing us to model bound ADP-Pi [Fig. 1(C)]. Exceptions to the overall conservation in the binding pocket include M389 (Q and S in E. coli DnaK and human Hsp70, respectively), which would interact with the side of the adenine moiety; C317 (Arginine in Hsp70), which packs against the top of the adenine and may form a polar interaction with the adenine N7 atom; and N64 (a tyrosine in Hsp70), which interacts with the α-phosphate. These sequence differences in the nucleotide-binding pocket consistently differentiate mitochondrial Hsp70s from the eukaryotic cytosolic Hsp70s. In particular, N64 and M389 are conserved in Mortalins from protists and fungi to mammals (Supporting Information Figs. S1 and S2). C317 is replaced by isoleucine in some Mortalins; the E. coli DnaK equivalents of C317 and N64 are also isoleucine and asparagine, highlighting Mortalin's evolutionary relationship to the prokaryotic chaperones. M389 appears to be specific to the mitochondrial Hsp70s and is not conserved in other Hsp70 families, including endoplasmic reticulum-resident Hsp70 (Grp75/BiP/HSA5) and other cytosolic subfamilies (data not shown).

To explore the functional significance of the sequence differences in the nucleotide-binding pocket, we compared the nucleotide affinities of the Mortalin- and human Hsc70-NBDs. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements of ADP + Pi and ADP binding to the Mortalin-NBD (Table II; Supporting Information Fig. S3) show that its affinity is weaker than that of Hsc70. We also measured the affinity of a Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R mutant, in which Mortalin residues were replaced by their Hsp70/Hsc70 counterparts. Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R bound ADP + Pi even more weakly than wild-type Mortalin-NBD and ADP binding was too weak to quantitate by ITC. A Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R/M389S triple mutant was unstable and expressed poorly in E. coli and we were unable to test it comprehensively. However, a small amount of the purified triple mutant exhibited similarly low affinity for ADP + Pi as the double mutant in ITC experiments (data not shown). Similarly to Hsp70/Hsc7031 and consistent with our crystal structure, phosphate (Pi) increased the affinity of ADP for Mortalin-NBD or for Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R. We also measured the affinity of hydrolysis-defective Hsc70-NBD and Mortalin-NBD mutants35 for ATP. It should be noted that Hsc70-T204 (and presumably Mortalin-T249) interact with the γ-phosphate of ATP36 and their mutation likely leads to a lower affinity for ATP than that of the corresponding wild-type proteins. Nevertheless, the affinities of Mortalin-NBDT249A and Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R/T249A for ATP were also substantially weaker than that of Hsc70-NBDT204A (Table II; Supporting Information Fig. S3).

Table II.

Nucleotide Affinities of the Mortalin- and Hsc70-NBDs

| Nucleotide | Protein | Kd (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| ADP-Pi | Hsc70-NBD | 0.029 ± 0.002 |

| Mortalin-NBD | 5.3 ± 0.3 | |

| Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R | 16 ± 3 | |

| ADP | Hsc70-NBD | 0.052 ± 0.02 |

| Mortalin-NBD | 620 ± 110 | |

| Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R | n.d.b | |

| ATP | Hsc70-NBDT204A | 3.9 ± 0.7 |

| Mortalin-NBDT249A | 29 ± 7 | |

| Mortalin-NBDN64Y/C317R/T249A | n.d.b |

aDissociation constants (Kd) measured by ITC; see Supporting Information Figure S2 for raw ITC data and titration curves.

ITC signal too weak/noisy to properly calculate dissociation constants. We estimate that the Kd values are in the millimolar range for these measurements.

The nucleotide affinity is, thus, not determined solely by the proximal residues of the nucleotide-binding pocket. Conformational dynamics of the respective NBDs, which are influenced by segments outside the nucleotide-binding pocket, likely influence their effective nucleotide affinities and dissociation/exchange rates.1,34 Recent studies showed that full-length Ssc1, a Mortalin orthologue in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, fluctuates between nucleotide-free and bound states even in the presence of substantial concentrations of ATP or ADP, and also hint that the overall nucleotide affinity is lower in Mortalin than in other Hsp70 family members.37 A structure-based alignment of the Hsp70, Mortalin, and DnaK NBD sequences shows nonconserved residues that mediate intersubdomain contacts or are located in hinges between the subdomains (Supporting Information Fig. S2). These residues may contribute to differences in conformational dynamics between the Hsp70 and Mortalin-NBDs.

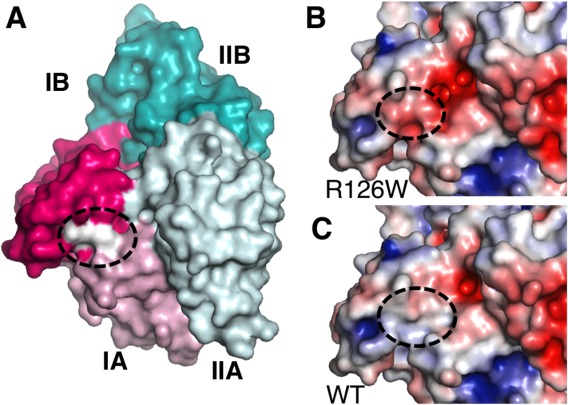

Disease-associated mutation on the surface of Mortalin-NBD

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a general hallmark of dopaminergic neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Genetic studies identified three Mortalin mutants in Parkinson's disease patients: P509S and A476T in the SBD, and R126W in the NBD.11,38 The R126W mutation may promote aggregation in vivo leading to loss of mortalin function.39 R126 lies on the surface of the NBD at the interface between subdomains IIA and IA (Fig. 2). Interestingly, only a minority of Trp rotamers are accommodated at this position, and even these require movement of the nearby sidechains of Q201 and D130. Replacement of R126 by tryptophan and local remodeling may create a more acidic surface patch (Fig. 3), or the poor packing of the Trp may destabilize the Mortalin fold. Either of these alterations could contribute to aggregation and suppression of function of the mutant Mortalin protein.

Figure 2.

Location and effect of the Parkinson's disease mutation R126W. (A) Location of R126 mapped onto the Mortalin-NBD surface. NBD subdomains are colored and labeled as in Figure 1. Location of R126 and the nearby D130 and Q201 residues are shown as a white patch and marked by a dashed oval. (B) Surface electrostatic potential of the R126W mutant calculated using APBS,62 within a range of −5(red) to +5kT (blue). The dashed oval marks the location of W126, D130, and Q201. (C) Surface electrostatic potential of wild-type Mortalin-NBD, colored and marked as in panel (B). Use this link to access the interactive version of this figure.

Figure 3.

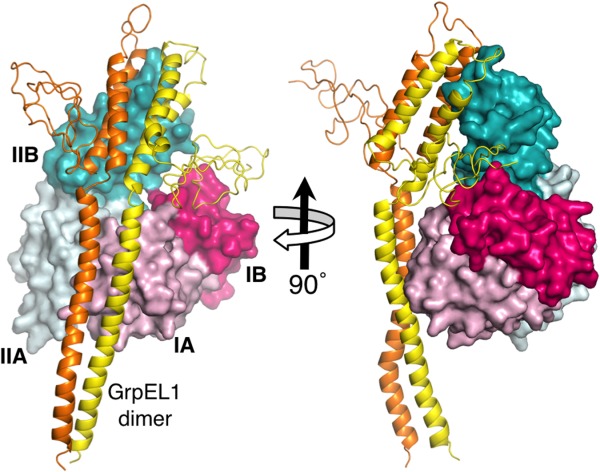

Homology model of the Mortalin-NBD in complex with mitochondrial GrpEL1. Mortalin-NBD subdomains are colored as in Figure 1. The protomers of the GrpEL1 dimer are colored yellow and orange. Detailed views of the interactions are shown in Supporting Information Figure 4.

Model of interaction between Mortalin-NBD and mitochondrial GrpEL1

Mortalin interacts with a mitochondrial J-domain protein Tid-1, the cochaperone Hep, and two potential nucleotide exchange factors in mitochondria.40–42 In analogy with other Hsp70-family members, these cochaperones accelerate the low intrinsic rates of ATP hydrolysis and ADP/ATP exchange, respectively, and are essential for effective chaperone function. Further emphasizing the connection between Mortalin and prokaryotic Hsp70s, the nucleotide exchange factors are homologous to GrpE, the nucleotide exchange factor for DnaK. Termed GrpELike1 and −2 (GrpEL1 and GrpEL2), they are approximately 43% identical and 65% similar to each other. We generated a model of the Mortalin-NBD in complex with a homology model of human GrpEL1 (Fig. 4), based on structures of E. coli and Geobacillus kaustophilus DnaK:GrpE complexes.43,44 We modeled the Mortalin-NBD in an open conformation, which is characteristically induced by GrpE on DnaK, by tilting subdomain IIB away from subdomain IB about the IIA/IIB hinge. GrpEL1 has moderate homology to bacterial GrpEs (∼25% identical and ∼45% similar). However, key interactions are conserved; the helical portion of the asymmetric GrpEL1 dimer “head” primarily contacts subdomain IIB while the extended wing of one of the GrpEL1 protomers contacts subdomain IB (Fig. 4). The coiled-coil “tail” of the GrpEL1 dimer also makes contacts with subdomain IA. The putative contact residues of GrpEL1 and Mortalin are shown in closeups in Supporting Information Figure S4.

Figure 4.

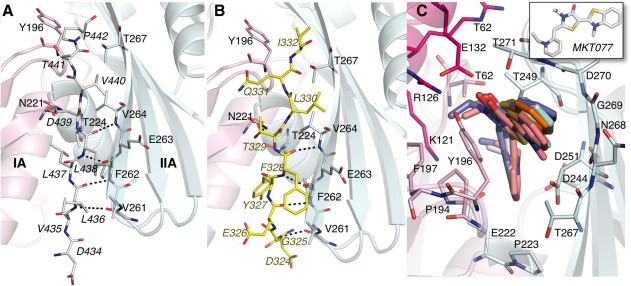

Models of Mortalin-NBD binding to p53 and MKT-077. The Mortalin NBD is colored and labeled as in Figure 1. The NBD secondary structure cartoon is shown partly transparent for clarity. (A) Model of the interaction between the Mortalin NBD-SBD interdomain linker sequence (shown as white stick model with italicized labels) and the β-sheet of subdomain IIA. The model was constructed based on the ATP-bound structure of DnaK (PDB IDs 4B9Q, 4NJ4).46,47 (B) Interaction between p53 sequence located N-terminal to the p53 tetramerization domain and the same β-strand as in panel (A). The p53 sequence is shown as yellow sticks and labeled in yellow italics. (C) Five high-scoring poses of MKT-077 docked to the Mortalin-NBD. MKT-077 models are shown as thick sticks. The inset shows the structure of MKT-077 (no hydrogens are shown). In the docked orientations, the methyl-benzothiazoline moiety of MKT-077 is closest and the ethylpyridine moiety is furthest from the viewer. Selected Mortalin residues within 4 Å of MKT-077 are shown and labeled. The region of the NBD shown corresponds to the upper portion of the regions shown in panels (A and B).

Interaction of Mortalin-NBD with p53 and MKT-077

Several studies have probed the interaction of Mortalin with p53 and obtained evidence for a noncanonical substrate recognition mode that differs from the well-understood binding of substrates to the SBDs of Hsp70-family chaperones. Deletion analysis identified a putative p53-interacting region on the Mortalin NBD, encompassing Residues 253–282.45 These residues define a surface formed by two β-strands and a hairpin turn in subdomain IIA, and extend into a helix from subdomain IIB. One of these strands serves as a docking site for the NBD-SBD interdomain linker in the putative ATP-bound form of Mortalin, in analogy with the structure of ATP-bound DnaK.46,47 A segment from the Mortalin interdomain linker (434DVLLLDV440) is identical to the equivalent segment in DnaK and likely forms an additional parallel beta strand to dock against subdomain IIA [Fig. 4(A)]. Interestingly, a comparable sequence (323LDGEYFTLQIRGRE337) is present near the tetramerization domain of p53. A peptide mimic of this sequence disrupts Mortalin:p53 interaction.48 These residues form a flexible linker between the tetramerization helix and the preceding core/DNA-binding domains of p53. We docked residues from this sequence (324DGEYFTLQI332), mimicking the docking of the Mortalin interdomain linker [Fig. 5(B)], to model how the Mortalin-NBD may interact with p53. This model does not conflict with or exclude the reported binding of the Mortalin-SBD to other regions of p53 such as the p53 negative regulatory domain.49 A recent in vitro study suggests that Mortalin Residues 260–288 on the NBD may form another binding site for the p53 C-terminal negative regulatory domain.50 In addition, the association between Mortalin and p53 may be regulated by Mortalin's J-domain cochaperone Tid1, which also binds to p53.51 The Mortalin NBD region encompassed by Residues 253–282 includes a potential interaction site for the J-domain of Tid1,53 suggesting that Tid1 could pass p53 onto the Mortalin SBD while itself docking onto the Mortalin NBD.

The putative binding site for the rhodacyanine dye MKT-077, which downregulates p53 sequestration by Mortalin, was mapped to Mortalin Residues 252–310, overlapping with the putative p53- and/or Tid-1-interacting sites of the Mortalin NBD.25 A binding site for MKT-077 on human Hsc70 has been proposed based on NMR and computational docking data.30 Based on these studies, we modeled MKT-077 sandwiched between Mortalin Residues 267–271 and the sidechain of Y196 [Fig. 5(C)]. At this position, the MKT-077 may disrupt p53 docking by perturbing the conformation of the interacting Mortalin β-strand (Residues 260–270). As the Y196-containing loop likely approaches Residues 267–271 in the ATP-bound conformation of Mortalin,46,47 MKT-077 may also destabilize the ATP-bound conformation and indirectly prevent the association of Tid1. Thus, there are several potential ways for MKT-077 to both block Mortalin function generally and to specifically prevent the association between Mortalin and p53.

Conclusions

Together with the recent structure of the Mortalin-SBD (PDB ID 3N8E), our crystal structure of the NBD confirms the overall structural similarity between Mortalin to the prokaryotic DnaK chaperones and the diversified eukaryotic Hsp70-family members. Structural characterization of full-length Mortalin in the nucleotide-free, ATP-, and ADP-bound states would be a valuable next step in characterizing this important chaperone. Our results establish a structural basis to elucidate the interactions of Mortalin with mitochondrial cochaperones, with the mitochondrial import machinery and with substrates both within mitochondria and in the cytosol. Finally, the NBD structure may inform the design of more potent and specific Mortalin-targeting compounds, including direct competitors of ATP as well as allosteric compounds that function similarly to MKT-077.30 Differential and context-specific targeting of Mortalin offers a potentially important therapeutic avenue for the treatment of cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, or other pathologies characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of Mortalin-NBD

A pET28+-Mortalin plasmid containing the coding sequence for human Mortalin Residues 52–679) was used as a template.54 The Mortalin NBD sequence was amplified by polymerase chain reaction and inserted into the pGST||2 expression vector.55 The resulting plasmid, pGST||2-Mortalin(52–431), codes for an N-terminal glutathione-S-transferase tag, followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site and human Mortalin Residues 52–431. Sequence-verified constructs were transformed into E. coli Rosetta2 (DE3) cells (EMD Chemicals) for expression.

The GST-tagged Mortalin NBD was expressed in Luria-Bertani media induced with 0.25 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside and shaken for 20 h at 20°C. Cultures were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 20-mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50-mM NaCl, 5-mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mg/mL lysozyme (Sigma), 20 µg/mL DNaseI (MP Biomedicals), 100 µg/mL 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (Gold Biotechnology). Resuspended cells were flash-frozen, thawed, and lysed overnight at 4°C. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, loaded onto a glutathione Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (buffer A), and washed with 15 column volumes of buffer A. The Mortalin-NBD was cleaved on the column with 0.75 mg of His6-tagged TEV protease56 overnight. A 5-mL HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) and an additional glutathione Sepharose column were added to bind the TEV protease and cleaved GST. The columns were washed with three column volumes of buffer A, and the flow through containing Mortalin NBD was collected. The flow through was dialyzed into 20-mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7, concentrated by centrifugation and applied to a Superdex-70 16/60 size exclusion column. The protein was eluted in the same buffer and peak fractions were applied to a HiTrap Blue HP column (GE Healthcare), washed with five column volumes of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.7 and eluted with a 10 column volume gradient of 0–2 M NaCl, 20-mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0. The peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed into 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0.

Mortalin-NBD point mutants were generated from the wild-type construct by polymerase chain reaction using the Quikchange-II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) and verified by sequencing. Mortalin-NBD mutants were expressed and purified in the same manner as the wild-type protein construct. Wild-type and mutant Hsc70-NBD (human Hsc70 Residues 1–384) were cloned into the pHis||2 vector,55 expressed as 6xHis-tagged constructs and purified on a His-Trap HP Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), followed by Superdex-70 size exclusion and HiTrap Blue purification steps as described above.

Crystallization and structure determination

Fresh Mortalin-NBD was concentrated to 19 mg/mL by ultracentrifugal filtration and used for sitting drop crystallization trials, carried out with a Gryphon crystallization robot (Art Robbins Instruments). Sitting drops contained 0.2 µL of protein and 0.2 µL of well solution. Initial screening was carried out using the sparse matrix crystallization screens JCSG Core I-IV (Qiagen) and MCSG 1–4 (Microlytic). Optimizations of initial hits from the sparse matrix screens identified an optimal reservoir solution of 0.2 M di-ammonium tartrate and 20% PEG 3350. Crystals were cryoprotected by brief transfer through LV CryoOil (MiTeGen) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 1.00 Å on beamline 4.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and processed using XDS.57 Phases were calculated by molecular replacement using the PHASER58 component of PHENIX.59 The structure of human Hsp70 in the ADP- and Mg-bound state (PDB ID 3ATU) was utilized as the search model.31 Automated rebuilding of the molecular replacement solution in PHENIX AutoBuild60 allowed for placement of human Mortalin Residues 54–334 and 337–429. The rebuilt model was subjected to iterative rounds of model building in Coot61 and refinement in PHENIX. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 4KBO). Stereochemical and geometric analyses of the Mortalin-NBD structure were conducted with MolProbity.62 All molecular structure figures were prepared with PyMOL.63 Surface electrostatics shown in Figure 2 were calculated using the APBS64 plugin for PyMol.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Calorimetric measurements were performed at 25°C using MicroCal iTC200 or VP-ITC isothermal titration calorimeters (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). Proteins were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0. Protein concentrations were determined using a 660 nm Protein Assay (Pierce) and were 20–150 µM. Nucleotides were freshly dissolved in the above buffer at 500 µM to 3 mM concentration and, if needed, the pH was adjusted to 8.0 with NaOH. For ADP + Pi binding measurements, the protein and nucleotide buffers also contained 5-mM Na2HPO4. Binding isotherms were corrected by subtracting results from a control experiments with nucleotide injected into buffer. Dissociation constants (Kd) were estimated by nonlinear least-squares fitting to a single-site binding model using Origin v7.0 (OriginLab).

Homology and computational modeling

To model the Mortalin-NBD complex with GrpEL1, Mortalin-NBD subdomains were first aligned to their DnaK-NBD counterparts within the G. kaustophilus DnaK/GrpE complex structure44 (PDB ID 4ANI). A GrpEL1 homology model was generated using the I-Tasser web interface,65 which yielded a very good-quality model (C-score = 1.38, Rmsd = 2.3 ± 1.7 Å). Peptide bonds linking the subdomains were minimally rebuilt using Coot61 to ensure realistic stereochemistry. The reconstructed Mortalin-NBD/GrpEL1 complex was subjected to 10 individual rounds of all-atom refinement using Rosetta relax.66,67 The lowest total Rosetta energy score (total_energy) decoy from the family of 10 models was chosen as the representative model.

To model the p53 interaction with the Mortalin-NBD, an initial docking pose for human p53 Residues 324–332 was modeled in Coot61 utilizing structures of ATP-bound DnaK (PDB IDs 4B9Q and 4JN4) as templates.46,47 The initial docking pose was prepacked with Rosetta68 to produce a starting model for Mortalin-NBD/p53 Rosetta FlexPepDock calculations.69 A family of 500 decoys were generated by Rosetta FlexPepDock using extra Chi1 rotamers, extra aromatic-Chi2 rotamers, and backbone-backbone hydrogen bond distance constraints to maintain the β-sheet hydrogen bonding pattern between p53 Residues E326–F328 and Mortalin Residues F262–V264. The decoy with the lowest Rosetta interface score (I_sc) was used as a representative model.

To dock MKT-077 to the Mortalin-NBD, an initial docking pose was prepared by aligning the Mortalin-NBD to the yeast Hsc70-NBD utilized in previously described Hsc70/MKT-077 AUTODOCK calculations.30 The best MKT-077 docking pose identified in this study was added to the aligned Mortalin-NBD and prepacked with Rosetta68 to generate the starting model. Ligand geometry and charge were optimized using PHENIX eLBOW70 and used to prepare the Rosetta ligand parameter file for MKT-077. RosettaLigand71 docking calculations allowed for backbone and side-chain flexibility with extra Chi1 and aromatic-Chi2 rotamers for Mortalin-NBD and full flexibility for MKT-077 with permitted ligand translations away from the starting pose of up to ±5 Å along the x, y, and z axes. An ensemble of 10,000 decoys was generated and the top five percent were clustered based on overall Rosetta energy score (total_score). A representative family of models was selected from the top five percent cluster as the five decoys with the lowest Rosetta interface score (I_sc).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Drs. Satya Yadav and Smarajit Bandyopadhyay and the Molecular Biotechnology Core of the Lerner Research Institute (Cleveland Clinic) for access to and assistance with isothermal titration calorimetry instrumentation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Information

References

- 1.Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:670–684. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daugaard MM, Rohde MM, Jäättelä MM. The heat-shock protein 70 family: highly homologous proteins with overlapping and distinct functions. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3702–3710. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadhwa R, Kaul SC, Ikawa Y, Sugimoto Y. Identification of a novel member of mouse hsp70 family. Its association with cellular mortal phenotype. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6615–6621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizzen LA, Chang C, Garrels JI, Welch WJ. Identification, characterization, and purification of two mammalian stress proteins present in mitochondria, grp 75, a member of the hsp 70 family and hsp 58, a homolog of the bacterial groEL protein. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20664–20675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaul SC, Deocaris CC, Wadhwa R. Three faces of mortalin: a housekeeper, guardian and killer. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schilke B, Williams B, Knieszner H, Pukszta S, D'Silva P, Craig EA, Marszalek J. Evolution of mitochondrial chaperones utilized in Fe-S cluster biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1660–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider HC, Berthold J, Bauer MF, Dietmeier K, Guiard B, Brunner M, Neupert W. Mitochondrial Hsp70/MIM44 complex facilitates protein import. Nature. 1994;371:768–774. doi: 10.1038/371768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Q, D'Silva P, Walter W, Marszalek J, Craig EA. Regulated cycling of mitochondrial Hsp70 at the protein import channel. Science. 2003;300:139–141. doi: 10.1126/science.1083379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarzer C, Barnikol-Watanabe S, Thinnes FP, Hilschmann N. Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC) interacts with the dynein light chain Tctex1 and the heat-shock protein PBP74. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Liu W, Song X-D, Zuo J. Effect of GRP75/mthsp70/PBP74/mortalin overexpression on intracellular ATP level, mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS accumulation following glucose deprivation in PC12 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;268:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-2996-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burbulla LF, Schelling C, Kato H, Rapaport D, Woitalla D, Schiesling C, Schulte C, Sharma M, Illig T, Bauer P, Jung S, Nordheim A, Schöls L, Riess O, Krüger R. Dissecting the role of the mitochondrial chaperone mortalin in Parkinson's disease: functional impact of disease-related variants on mitochondrial homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4437–4452. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadhwa R. Hsp70 family member, mot-2/mthsp70/GRP75, binds to the cytoplasmic sequestration domain of the p53 protein. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:246–253. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadhwa R, Takano S, Robert M, Yoshida A, Nomura H, Reddel RR, Mitsui Y, Kaul SC. Inactivation of tumor suppressor p53 by mot-2, a hsp70 family member. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29586–29591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dundas SR, Lawrie LC, Rooney PH, Murray GI. Mortalin is over-expressed by colorectal adenocarcinomas and correlates with poor survival. J Pathol. 2005;205:74–81. doi: 10.1002/path.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadhwa R, Takano S, Kaur K, Deocaris CC, Pereira-Smith OM, Reddel RR, Kaul SC. Upregulation of mortalin/mthsp70/Grp75 contributes to human carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2973–2980. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker C, Böttger S, Low B. Mortalin-based cytoplasmic sequestration of p53 in a nonmammalian cancer model. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1526–1530. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadhwa R, Takano S, Mitsui Y, Kaul SC. NIH 3T3 cells malignantly transformed by mot-2 show inactivation and cytoplasmic sequestration of the p53 protein. Cell Res. 1999;9:261–269. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Z, Izumi H, Kanai M, Kabuyama Y, Ahn NG, Fukasawa K. Mortalin controls centrosome duplication via modulating centrosomal localization of p53. Oncogene. 2006;25:5377–5390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baseler WA, Croston TL, Hollander JM. Functional Characteristics of Mortalin. In: Kaul S, Wadhwa R, editors. Mortalin Biology: Life, Stress and Death. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nomikos A, Dundas SR, Murray GI. Mortalin expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. In: Kaul S, Wadhwa R, editors. Mortalin biology: life, stress and death. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qu M, Zhou Z, Xu S, Chen C, Yu Z, Wang D. Mortalin overexpression attenuates beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res. 2011;1368:336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wadhwa R, Takano S, Taira K, Kaul SC. Reduction in mortalin level by its antisense expression causes senescence-like growth arrest in human immortalized cells. J Gene Med. 2004;6:439–444. doi: 10.1002/jgm.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu W-J, Lee NP, Kaul SC, Lan F, Poon RTP, Wadhwa R, Luk JM. Induction of mutant p53-dependent apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting stress protein mortalin. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1806–1814. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deocaris CC, Widodo N, Shrestha BG, Kaur K, Ohtaka M, Yamasaki K, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R. Mortalin sensitizes human cancer cells to MKT-077-induced senescence. Cancer Lett. 2007;252:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadhwa R, Sugihara T, Yoshida A, Nomura H, Reddel RR, Simpson R, Maruta H, Kaul SC. Selective toxicity of MKT-077 to cancer cells is mediated by its binding to the hsp70 family protein mot-2 and reactivation of p53 function. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6818–6821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilzer D, Saar M, Koya K, Fishelson Z. Mortalin inhibitors sensitize K562 leukemia cells to complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1428–1435. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Propper DJ, Braybrooke JP, Taylor DJ, Lodi R, Styles P, Cramer JA, Collins WC, Levitt NC, Talbot DC, Ganesan TS, Harris AL. Phase I trial of the selective mitochondrial toxin MKT077 in chemo-resistant solid tumours. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:923–927. doi: 10.1023/a:1008336904585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Britten CD, Rowinsky EK, Baker SD, Weiss GR, Smith L, Stephenson J, Rothenberg M, Smetzer L, Cramer J, Collins W, Von Hoff DD, Eckhardt SG. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the mitochondrial-specific rhodacyanine dye analog MKT 077. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuiderweg ERP, Bertelsen EB, Rousaki A, Mayer MP, Gestwicki JE, Ahmad A. Allostery in the Hsp70 chaperone proteins. Top Curr Chem. 2013;328:99–153. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rousaki A, Miyata Y, Jinwal UK, Dickey CA, Gestwicki JE, Zuiderweg ERP. Allosteric drugs: the interaction of antitumor compound MKT-077 with human Hsp70 chaperones. J Mol Biol. 2011;411:614–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arakawa A, Handa N, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S. Biochemical and structural studies on the high affinity of Hsp70 for ADP. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1367–1379. doi: 10.1002/pro.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holm L, Rosenström P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shida M, Arakawa A, Ishii R, Kishishita S, Takagi T, Kukimoto-Niino M, Sugano S, Tanaka A, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S. Direct inter-subdomain interactions switch between the closed and open forms of the Hsp70 nucleotide-binding domain in the nucleotide-free state. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:223–232. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909053979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brehmer D, Rüdiger S, Gässler CS, Klostermeier D, Packschies L, Reinstein J, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Tuning of chaperone activity of Hsp70 proteins by modulation of nucleotide exchange. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:427–432. doi: 10.1038/87588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barthel TK, Zhang J, Walker GC. ATPase-defective derivatives of Escherichia coli DnaK that behave differently with respect to ATP-induced conformational change and peptide release. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5482–5490. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5482-5490.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaherty KM, Wilbanks SM, DeLuca-Flaherty C, McKay DB. Structural basis of the 70-kilodalton heat shock cognate protein ATP hydrolytic activity. II. Structure of the active site with ADP or ATP bound to wild type and mutant ATPase fragment. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12899–12907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sikor M, Mapa K, von Voithenberg LV, Mokranjac D, Lamb DC. Real-time observation of the conformational dynamics of mitochondrial Hsp70 by spFRET. EMBO J. 2013;32:1639–1649. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Mena L, Coto E, Sánchez-Ferrero E, Ribacoba R, Guisasola LM, Salvador C, Blázquez M, Alvarez V. Mutational screening of the mortalin gene (HSPA9) in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:1289–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goswami AV, Samaddar M, Sinha D, Purushotham J, D'Silva P. Enhanced J-protein interaction and compromised protein stability of mtHsp70 variants lead to mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3317–3332. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iosefson O, Sharon S, Goloubinoff P, Azem A. Reactivation of protein aggregates by mortalin and Tid1--the human mitochondrial Hsp70 chaperone system. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2012;17:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s12192-011-0285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naylor DJ, Stines AP, Hoogenraad NJ, Høj PB. Evidence for the existence of distinct mammalian cytosolic, microsomal, and two mitochondrial GrpE-like proteins, the Co-chaperones of specific Hsp70 members. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21169–21177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choglay AA, Chapple JP, Blatch GL, Cheetham ME. Identification and characterization of a human mitochondrial homologue of the bacterial co-chaperone GrpE. Gene. 2001;267:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrison CJ, Hayer-Hartl M, Di Liberto M, Hartl F, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the nucleotide exchange factor GrpE bound to the ATPase domain of the molecular chaperone DnaK. Science. 1997;276:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5311.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu C-C, Naveen V, Chien C-H, Chang Y-W, Hsiao C-D. Crystal structure of DnaK protein complexed with nucleotide exchange factor GrpE in DnaK chaperone system: insight into intermolecular communication. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21461–21470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.344358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul SC, Reddel RR, Mitsui Y, Wadhwa R. An N-terminal region of mot-2 binds to p53 in vitro. Neoplasia. 2001;3:110–114. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kityk R, Kopp J, Sinning I, Mayer MP. Structure and dynamics of the ATP-bound open conformation of Hsp70 chaperones. Mol Cell. 2012;48:863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qi R, Sarbeng EB, Liu Q, Le KQ, Xu X, Xu H, Yang J, Wong JL, Vorvis C, Hendrickson WA, Zhou L, Liu Q. Allosteric opening of the polypeptide-binding site when an Hsp70 binds ATP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:900–907. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaul SC, Aida S, Yaguchi T, Kaur K, Wadhwa R. Activation of wild type p53 function by its mortalin-binding, cytoplasmically localizing carboxyl terminus peptides. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39373–39379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iosefson O, Azem A. Reconstitution of the mitochondrial Hsp70 (mortalin)-p53 interaction using purified proteins--identification of additional interacting regions. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1080–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabizon R, Brandt T, Sukenik S, Lahav N, Lebendiker M, Shalev DE, Veprintsev D, Friedler A. Specific recognition of p53 tetramers by peptides derived from p53 interacting proteins. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahn BY, Trinh DLN, Zajchowski LD, Lee B, Elwi AN, Kim SW. Tid1 is a new regulator of p53 mitochondrial translocation and apoptosis in cancer. Oncogene. 2009;29:1155–1166. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trinh DLN, Elwi AN, Kim S-W. Direct interaction between p53 and Tid1 proteins affects p53 mitochondrial localization and apoptosisy as a target for cancer therapy? Oncotarget. 2010;1:405–422. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmad A, Bhattacharya A, McDonald RA, Cordes M, Ellington B, Bertelsen EB, Zuiderweg ERP. Heat shock protein 70 kDa chaperone/DnaJ cochaperone complex employs an unusual dynamic interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18966–18971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111220108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo W-I, Dizin E, Yoon T, Cowan JA. Kinetic and structural characterization of human mortalin. Protein Expr Purif. 2010;72:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheffield P, Garrard S, Derewenda Z. Overcoming expression and purification problems of RhoGDI using a family of “parallel” expression vectors. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;15:34–39. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapust RB, Tözsér J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001;14:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terwilliger TC, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Moriarty NW, Zwart PH, Hung L-W, Read RJ, Adams PD. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;D64:61–69. doi: 10.1107/S090744490705024X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2010;D66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schrodinger LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Version 1.3r1. Portland, OR. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raman S, Vernon R, Thompson J, Tyka M, Sadreyev R, Pei J, Kim D, Kellogg E, DiMaio F, Lange O, Kinch L, Sheffler W, Kim B-H, Das R, Grishin NV, Baker D. Structure prediction for CASP8 with all-atom refinement using Rosetta. Proteins 77 (Suppl. 2009;9):89–99. doi: 10.1002/prot.22540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chivian D, Baker D. Homology modeling using parametric alignment ensemble generation with consensus and energy-based model selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaudhury S, Berrondo M, Weitzner BD, Muthu P, Bergman H, Gray JJ. Benchmarking and analysis of protein docking performance in Rosetta v3.2. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raveh B, London N, Zimmerman L, Schueler-Furman O. Rosetta FlexPepDock ab-initio: simultaneous folding, docking and refinement of peptides onto their receptors. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. 2009;D65:1074–1080. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909029436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davis IW, Baker D. RosettaLigand docking with full ligand and receptor flexibility. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information