Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is usually considered a relatively rare pathogen of pyogenic liver abscess in healthy children. A 3-year-old girl presented with fever, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Ultrasonography of the abdomen showed multiple liver abscesses. During her stay in hospital, she developed portal vein thrombosis, hepatic encephalopathy, and multiorgan dysfunction. Her blood culture and pus culture grew pseudomonas aeruginosa. She was started on intravenous antibiotics and supportive treatment. Ultrasound guided aspiration was done and a pigtail catheter was inserted. However, she did not respond to the treatment and died on the 14th day of admission. The immune work up of the patient was normal. Through this case, we wish to highlight this unusual case of community-acquired pseudomonas aeruginosa liver abscess in a previously healthy child. Clinicians should be aware of this association for early diagnosis and timely management.

Keywords: Children, community-acquired, liver abscess, portal vein thrombosis, pseudomonas aeruginosa

INTRODUCTION

Although, liver abscesses have been recognized since the time of Hippocrates in 400 B.C., they still remain an important diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.[1] Children with liver abscess constitute about 25-79 per 100,000 pediatric admissions in world.[2] Most of the liver abscess are pyogenic with Staphylococcus being the commonest organism. The incidence of pseudomonas aeruginosa liver abscess (PALA) is around 2-6%.[3] Patients with PALA usually have an underlying chronic medical condition or a risk factor for Pseudomonas infection such as immunosuppressive drugs or disease.[4] We describe a rare case of rapidly progressive community-acquired PALA with portal vein thrombosis in a previously healthy child.

CASE REPORT

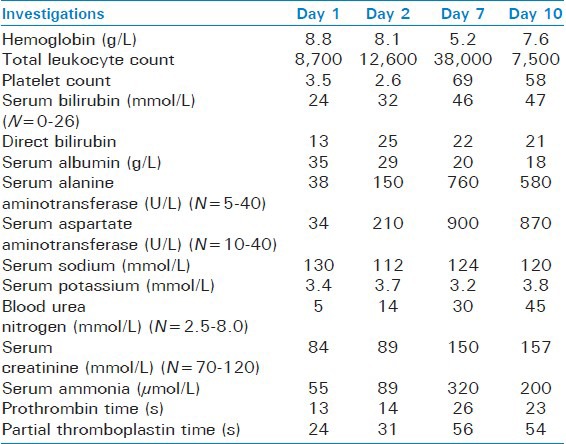

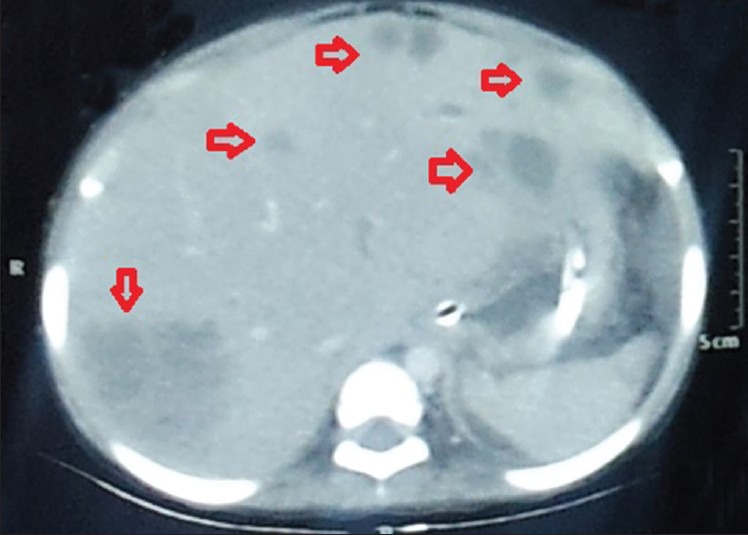

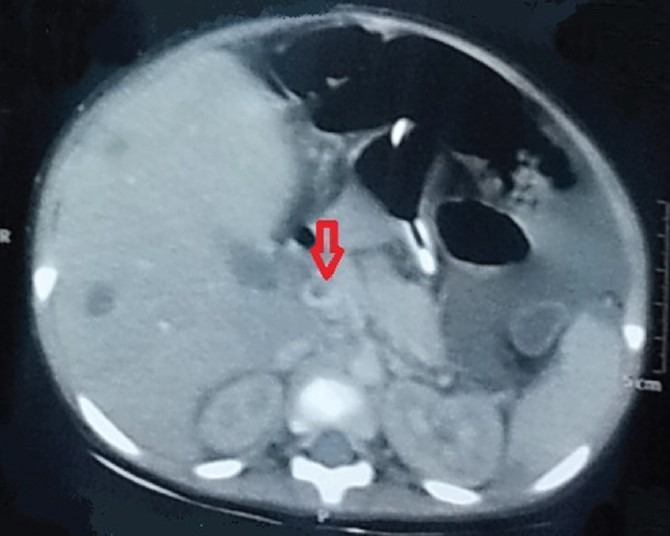

A 3-year-old female presented with high-grade fever and abdominal pain for 4 days, and non-bilious vomiting for 1 day. There were no bladder/bowel complaints, cough, cold, altered sensorium, convulsion, or icterus. The child was previously healthy with no past admissions. Birth and perinatal history were normal. On admission, she was febrile with a heart rate 130/min, respiratory rate 44/min, and blood pressure 98/60 mmHg. Mild pallor was present. There was no icterus or edema. Liver was tender with a span of 10 cm in the midclavicular line. Bowel sounds were sluggish. Rest of the systemic examination was normal. She was started on intravenous fluids and ceftriaxone. Investigations on the day of admission are shown in Table 1. Patient developed icterus and had one episode of generalized tonic-clonic convulsion lasting for about 10 min on the 2nd day of admission. Her sensorium became altered after the convulsion. Ultrasonography (USG) of abdomen done on the second day of admission revealed: 3.6 × 3.7 × 4 cm abscess in segment VII of right lobe, 3.3 × 3.6 × 3.5 cm sized abscess in segment II of left lobe, mild ascitis, and bilateral mild pleural effusion. As the abscesses had not liquefied, pediatric surgeons advised conservative management. Correction for hyponatremia, intravenous metronidazole, and calcium gluconate were started. Cerebrospinal fluid examination and computed tomography (CT) scan of brain were normal. Blood culture showed Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive to piperacillin, amikacin, and ciprofloxacin. Accordingly, the antibiotics were changed to piperacillin-tazobactum and amikacin on the 5th day. Syrup lactulose and oral ampicillin were added. On the 7th day, sensorium further worsened with increase in abdominal distension. Investigations on the 7th day are shown in Table 1. Packed cell transfusion and fresh frozen plasma transfusion were given. Ascitic fluid examination showed: 1,020 cells (80% neutrophils, 20% lymphocytes), protein 4.8 g%. Serial USG of the abdomen were done every alternate day to monitor the liver abscesses. USG on the 7th day showed increase in the size of previous liver abscesses with liquefaction and several new small abscesses throughout the liver parenchyma. USG guided aspiration was done. However, on the 8th day, the abscess in segment II ruptured and a pigtail catheter was inserted. CT scan of the abdomen showed: Hepatomegaly with multiple varying sized peripherally enhancing hypodense lesion noted in the liver parenchyma with the largest being in segment VII measuring 5.1 × 4.9 × 4.3 cm, gross ascitis, mild splenomegaly, and portal vein filing defect at pancreatic head region suggestive of thrombosis [Figures 1, 2, and 3]. Subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin was started. Cultures of the pus revealed Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a similar sensitivity pattern. However, patient continued to deteriorate, went into multiorgan dysfunction, and was ventilated on the 10th day of admission. Inotropes were started for the septic shock. Repeat blood cultures on the 10th day also revealed Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a similar sensitivity pattern. Human immunodeficiency virus testing by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was negative. Work up for primary immunodeficiency was done which was normal (complete blood count, absolute neutrophils count, mean platelet volume, lymphocyte subset analysis, serum immunoglobulin levels, and nitroblue tetrazolium test). On the 14th day, despite all resuscitative measures, patient died of septic multiorgan failure.

Table 1.

Serial investigations during the course of hospital stay

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen showing multiple, hypodense, cystic lesions of varying sizes scattered throughout liver parenchyma s/o abscesses

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen showing two large abscesses in liver; (a) segment II of left lobe and (b) segment VII of right lobe

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen showing filling defect in portal vein at pancreatic head region s/o thrombosis

DISCUSSION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is widespread in the environment and is usually regarded as a trivial commensal of the skin, mucous membranes, and intestinal tract.[5] Community-acquired Pseudomonas infections are rare and usually mild. There are only a few published reports of severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections occurring in previously healthy persons.[6] A PubMed search done in children (0-18 years) with keywords ‘Pseudomonas aeruginosa’ and ‘liver abscess’ revealed only one case of community-acquired PALA in a previously healthy child.[4] The authors have described a previously healthy 1.5-year-old boy who presented with fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. He had a liver abscess at right hepatic lobe. USG-guided aspiration and a 4-week course of antibiotics were given. The lesion resolved completely without complication. In contrast, our patient had multiple liver abscesses, developed portal vein thrombosis, and had a fulminant course. Pyogenic liver abscess commonly present with fever, anorexia, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Rare presentations include unexplained anemia, cough, breathlessness, pyrexia of unknown origin, or fulminant sepsis.[2] The mortality rate in patients with PALA is approximately four times as compared to those having liver abscess due to other organism.[7] Hence, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for this uncommon diagnosis, particularly when patients present without features pointing to hepatic pathology.

The various complications of pyogenic liver abscess are: Pleural/pericardial effusion, pneumonitis, fistula, Budd-Chiari syndrome, peritonitis, and hemobilia. Risk factors for complications include presence of jaundice, large/multiple abscess, acute abdomen, liver failure, and sepsis.[2] As seen in our case, left lobe abscesses are frequently associated with complications and require drainage more often than right lobe abscess.[8,9] Appropriate antibiotics, supportive therapy, and percutaneous drainage form the mainstay of the management.[2,3] Surgical drainage is reserved for patients who have failed percutaneous drainage, have multiple macroscopic abscess, and who require management for an underlying abdominal problem.[2] USG is the imaging modality of choice. CT scan is more sensitive for detecting smaller abscesses. Recurrences can take place, with most occurring within 3 months of treatment.[2,10] Underlying immunodeficiency should be suspected in such cases.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we report the second case of community-acquired PALA in a previously healthy child. Although rarely described in literature, clinicians should be aware of this association as timely diagnosis and early intervention can affect the outcome significantly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank the Dean of our institute for permitting us to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kar P, Kapoor S, Jain A. Pyogenic liver abscess: Aetiology, clinical manifestations and management. Trop Gastroenterol. 1998;19:136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma MP, Kumar A. Liver abscess in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:813–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02790392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulug M, Gedik E, Girgin S, Celen MK, Ayaz C. Pyogenic liver abscess caused by community-acquired multidrug resistance Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Braz J Infect Dis. 2010;14:218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo WT, Wang CC, Hsu ML, Chu ML. Pyogenic liver abscess caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a previously healthy child: Report of one case. Acta Paediatr Taiwan. 2000;41:98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calza L, Manfredi R, Marinacci G, Fortunato L, Chiodo F. Community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa sacro-iliitis in a previously healthy patient. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:620–2. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-7-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huhulescu S, Simon M, Lubnow M, Kaase M, Wewalka G, Pietzka AT, et al. Fatal Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in a previously healthy woman was most likely associated with a contaminated hot tub. Infection. 2011;39:265–9. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen WH, Chiu CH, Huang CH, Lin CH, Sun JH, Huang YY, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical analysis of 20 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43:877–82. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.599332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore SW, Millar AJ, Cywes S. Conservative initial treatment for liver abscesses in children. Br J Surg. 1994;81:872–4. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore SW, Lakhoo K, Millar AJ, Cywes S. Left-sided liver abscess in childhood. S Afr J Surg. 1994;32:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen PS, Schonheyder HC. Pyogenic hepatic abscess. A 10 year population-based retrospective study. APMIS. 1998;106:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]