Abstract

The first examples of Lewis base-catalyzed enantioselective boryl conjugate additions (BCA) that generate boron-substituted quaternary carbon stereogenic centers are disclosed. Reactions are performed in the presence of 1.0–5.0 mol % of a readily available chiral accessible N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) and commercially available bis(pinacolato)diboron; cyclic or linear α,β-unsaturated ketones can be used and rigorous exclusion of air or moisture is not necessary. The desired products are obtained in 63–95% yield and 91:9 to >99:1 enantiomeric ratio (e.r.). The special utility of the NHC-catalyzed approach is demonstrated in the context of an enantioselective synthesis of natural product anti-fungal (−)-crassinervic acid.

Keywords: boron, conjugate additions, enantioselective synthesis, N-heterocyclic carbenes, organic synthesis, quaternary carbons

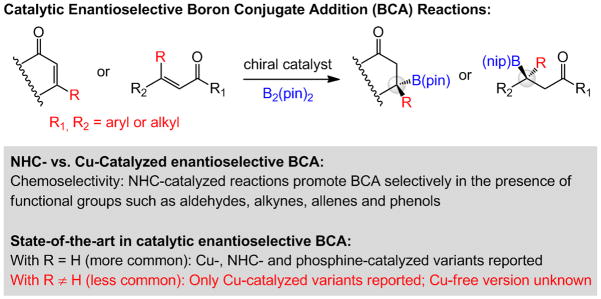

Reliable, efficient, and selective catalytic methods for synthesis of organoboron compounds are of considerable importance.[1] A challenge in organoboron chemistry is the development of catalytic protocols that furnish C–B bonds enantioselectively. There are enantioselective protocols for boron-hydride,[2] diboron,[3] proto-boryl,[4] and conjugate additions[5] to unsaturated compounds as well as allylic substitutions[6] that form B-substituted stereogenic centers and are promoted by transition metal-containing catalysts; related boryl additions to imines have been introduced as well.[7] In the case of boron conjugate addition (BCA) reactions, chiral Lewis base catalysts provide effective alternatives to the Cu-based complexes (Scheme 1);[8] chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) promote enantioselective BCA,[9] offer distinctive chemoselectivity profiles that are otherwise unavailable (Scheme 1).[8d] The large majority of the above protocols, however, relate to the formation of tertiary C–B bonds, and the small number of disclosures focused on the difficult enantioselective BCA processes that generate boron-substituted quaternary carbon centers[10,11] have remained in the domain of Cu catalysis.[12] The lone report involving allylic substitutions furnishing allyl–B(pin) products involves the use of an enantiomerically pure Cu-containing complex.[6b] To the best of our knowledge, there are no examples of Lewis base-catalyzed enantioselective reactions that furnish quaternary B-substituted carbons; such transformations would constitute a notable addition to the collection of catalytic enantioselective C–B bond forming processes.

Scheme 1.

Comparison of Cu-catalyzed and Cu-free enantioselective boron conjugate addition (BCA). B(pin) = (pinacolato)boron.

Herein, we disclose the first instances of Lewis base-catalyzed enantioselective BCA transformations that deliver cyclic or acyclic products with a boron-substituted quaternary carbon; products are obtained in 63–95% yield and 91:9 to >99:1 enantiomeric ratio (e.r.). The catalytic method’s unique features are highlighted by an enantioselective synthesis of natural product crassinervic acid.

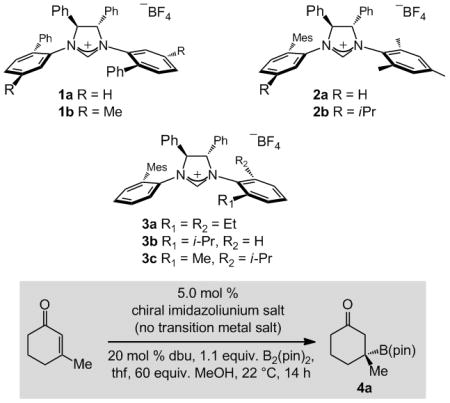

We first probed a number of easily accessible chiral NHCs that might be used to catalyze the formation of 4a efficiently and enantioselectively (Table 1). C2-Symmetric carbenes derived from 1a–b promote the BCA in moderate yield and e.r. (entries 1–2, Table 1). There is complete substrate consumption in 14 h when C1-symmetric 2a[13] is used; 4a is obtained in 88:12 e.r. (entry 3). Reaction with the m-iPr-substituted derivative 2b is less efficient and selective (68% conv., 67:33 e.r.; entry 4). When the NAr moieties of the NHC catalysts are dissymmetric (i.e., 3a–c in entries 5–7), BCA is efficient (>90% conv.) and highly enantioselective (>90:10 e.r.). Transformation with 3c furnishes 4a in 90% yield and 96:4 e.r. Additional noteworthy points are:

Table 1.

Examination of chiral imidazolinium salts as catalyst precursors.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Imidazolinium Salt | Conv. [%][b] | Yield [%][c] | e.r.[d] |

| 1 | 1a | 53 | 46 | 84:16 |

| 2 | 1b | 96 | 85 | 84:16 |

| 3 | 2a | >98 | 79 | 88:12 |

| 4 | 2b | 68 | 54 | 67:33 |

| 5 | 3a | >98 | 74 | 91.5:8.5 |

| 6 | 3b | 91 | 82 | 90:10 |

| 7 | 3c | >98 | 90 | 96:4 |

Reactions were performed under N2 atmosphere.

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%).

Yields of isolated and purified products (±5%).

Determined by GC analysis (±2%); see the Supporting Information for details. dbu = 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene; Mes = 2,4,6-Me3C6H2.

When the reaction is carried out with 1.0 mol % 3c and 5.0 mol % dbu, under otherwise identical conditions, there is 87% conversion to 4a (84% yield, 95:5 e.r.).

Rigorous exclusion of air and moisture is not required with the NHC-catalyzed transformations; 4a can be isolated in 92% yield and 95:5 e.r. when the reaction is performed in a typical fume hood.[14

Preparation of 3c is more efficient[14] than the catalyst precursor identified previously as optimal for BCA of the disubstituted cyclic enones.[8d]

Generally, NHC-catalyzed BCA processes that furnish B-substituted quaternary carbon stereogenic centers are more enantioselective than those involving disubstituted cyclic enones (e.g., β-B(pin)-substituted cyclohexanone formed in 87:13 e.r. vs. 96:4 e.r. for 4a).

When the transformation in entry 7 of Table 1 is carried out with 5.0 mol % CuCl, 4a is obtained in only 67:33 e.r. (>98% conv., 89% yield), underscoring the disparate mechanistic attributes of the NHC-catalyzed pathways.

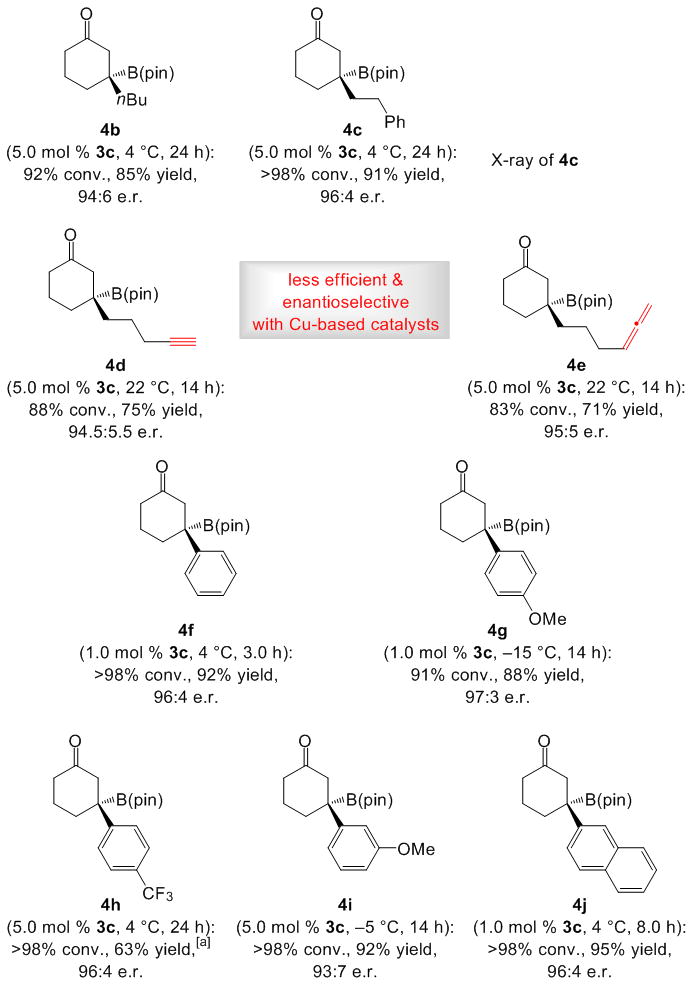

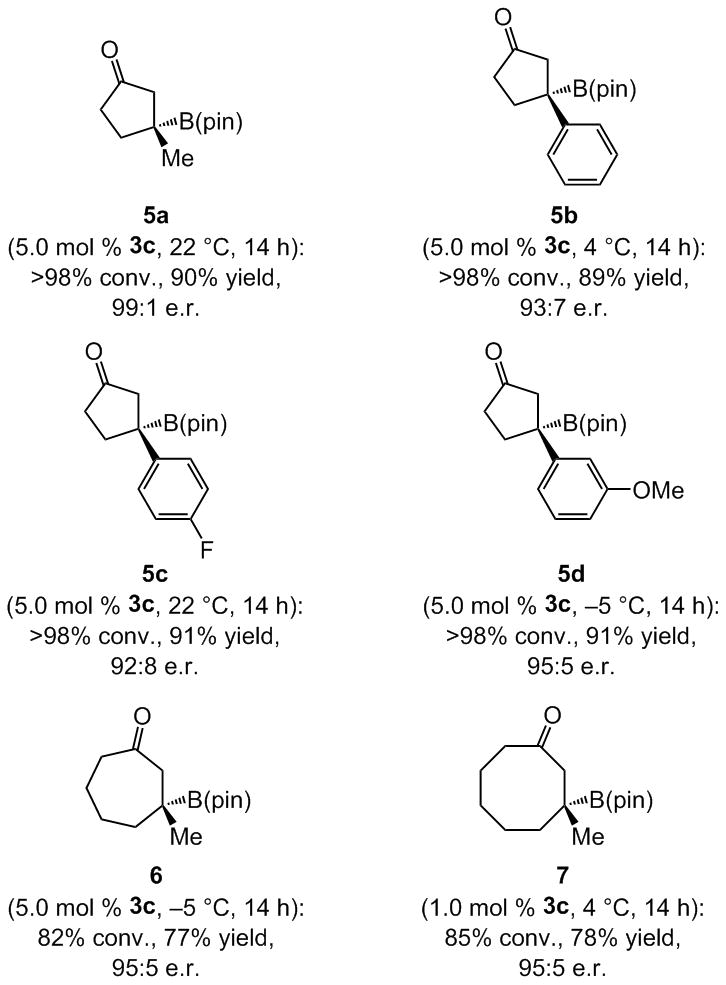

β-Substituted cyclohexenones, including those containing an alkyl (cf. 4b–e) or different aryl groups (cf. 4f–j), undergo NHC-catalyzed BCA to afford products in 63–95% yield and 93:7–97:3 e.r. (Scheme 2). Alkyl-substituted cyclic enones with a terminal alkyne (cf. 4d) or an allene (cf. 4e) are effective substrates. As the data for 4f–g and 4j indicate, 1.0 mol % 3c and 5.0 mol % dbu may be used with similar effectiveness. Catalytic BCA to enones with a relatively bulky substituent is somewhat less enantioselective; for example, the transformation of β-iPr-cyclohexenone delivers the expected β-boryl-cyclohexanone in 71% yield (75% conv.) and 86:14 e.r. (at 4 °C). The X-ray structure of 4c establishes the absolute stereochemistry of the BCA process.[15] When enantioselective synthesis of alkyne-containing 4d was attempted under the Cu-catalyzed conditions introduced by Shibasaki (12 mol % (R,R)-QuinoxP*, 10 mol % CuPF6(MeCN)4, 15 mol % LiOtBu, 1.5 equiv. B2(pin)2, dmso, 22 °C, 12 h), [12a] the product was isolated in 45% yield and 88:12 e.r.; with allene-bearing 4e, a complex mixture of unidentified products was formed. Such discrepancies are likely rooted in competitive reaction of the Cu–B(pin) complex with alkyne[16] and allene moieties.[17]

Scheme 2.

β-Boryl cyclohexenones can be accessed efficiently and enantioselectively. For general conditions see Table 1. [a] Proto-deboration byproduct formed (ca. 30%); 63% is the yield of pure 4h.

β-Substituted cyclopentenones undergo reaction to furnish 5a–d in 89–91% yield and 92:8–99:1 e.r. (Scheme 3). Additions to cyclopheptenone (cf. 6) and (for the first time) cyclooctenone (cf. 7) afford the desired products in 77–78% yield and 95:5 e.r.

Scheme 3.

NHC-catalyzed BCA reactions can be performed with five- or seven- and eight-membered enones.

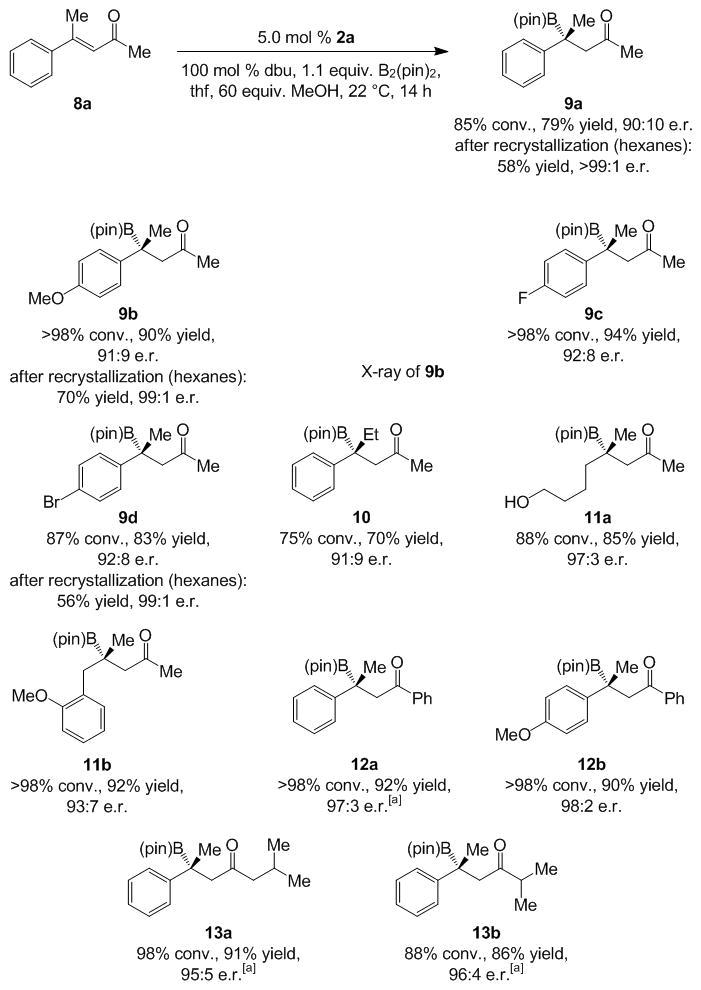

Transformations of acyclic aryl- or alkyl-substituted enones[18] deliver linear β-boryl ketones in 56–94% yield and up to >99:1 e.r. (Scheme 4). In some cases, simple recrystallization delivers materials of exceptional enantiomeric purity. Unlike cyclic enones, reactions proceed most enantioselectively with imidazolinium salt 2a.[19] For example, when 3c is used in the NHC-catalyzed BCA to enone 8b, β-boryl ketone 9b is isolated in 69% yield and 89:11 e.r. (vs. 90% yield and 91:9 e.r.). We have shown that BCA promoted by a chiral NHC–Cu complex leading to phenylketone 12a proceeds with lower selectivity [12b] in spite of being performed at −78 °C (82.5:17.5 in 24 h vs. 97:3 e.r. with 2a at 35 °C in 14 h).

Scheme 4.

Efficient and highly enantioselective NHC-catalyzed BCA reactions of acyclic enones. [a] Performed at 35 °C.

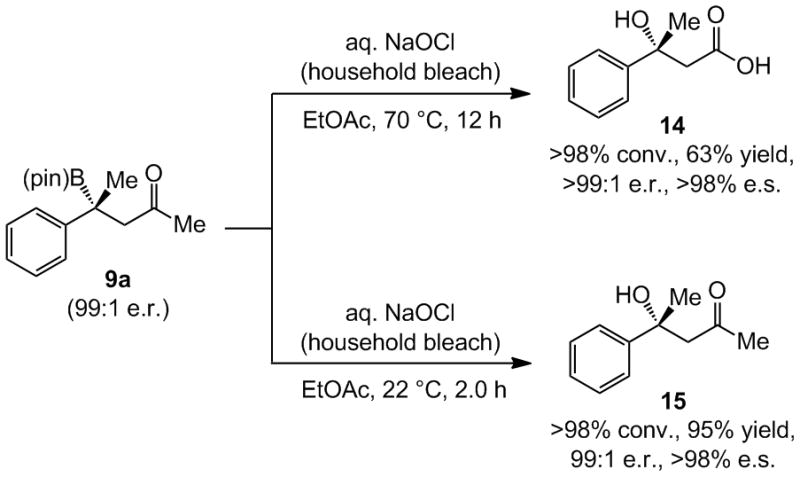

A deficiency of the NHC–Cu-catalyzed BCA is its ineffectiveness with enoates. We have established that treatment of a β-boryl product with common household bleach for 12 hours at 70°C[20] converts the C–B bond to a tertiary alcohol and the methyl ketone to a carboxylic acid (Scheme 5). At room temperature, β-hydroxyl ketone 15 is obtained in 95% yield after two hours.[21]

Scheme 5.

Subjection of an enantiomerically enriched BCA product to common bleach at room temperature affords the ketone aldol product or the derived β-hydroxy-acid (e.s. = product enantiomeric excess/substrate enantiomeric excess x 100).

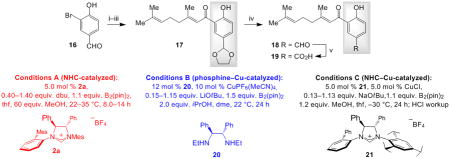

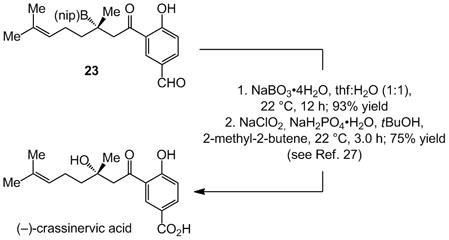

The study of enantioselective synthesis of anti-fungal natural product (−)-crassinervic acid,[22] elucidates the advantages of present approach [Table 2 and Eq. (1)].[23] It should be noted that generally efficient and enantioselective aldol additions to ketones are yet to be developed.[24] Under NHC-catalyzed and two of the more effective conditions involving phosphine- and NHC–Cu complexes (conditions A–C, respectively), there is complete consumption of acetal-containing enone 17, but it is the NHC-catalyzed BCA that delivers the highest e.r. (84:16 vs. 60:40 and 61:39). Subjection of 18, containing a phenol and an aldehyde group, to the NHC-catalyzed BCA conditions affords 23 in 72% yield and 95:5 e.r. On the contrary, treatment with the chiral Cu complex derived from diamine 17, effective for BCA to linear β,β-disubstituted ketones,[12c] affords the desired product in only 19% yield; with 21[12b] as the catalyst source, <2% conversion is observed.[25] Finally, when 19, containing a phenol and a carboxylic acid is used, only the NHC-catalyzed process is efficient. Oxidation of 23 with NaBO3 affords the tertiary alcohol in 93% yield [Eq. (1)], which has been converted to the target molecule (75% yield).[26]

Table 2.

Comparison of different Approaches en Route to (−)-Crassinervicn Acid.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Conditions | Conv. [%][b] | Yield [%][c] | e.r.[d] |

|

| ||||

22 |

A; 0.4 equiv. dbu, 22 °C, 14 h | >98 | 63 | 84:16 |

| B; 0.15 equiv. LiOtBu, 22 °C, 24 h | 87 | 78 | 60:40 | |

| C; 0.13 equiv. NaOtBu, −30 °C, 24 h | >98 (to 23) | 82 (of 23) | 69:31 | |

|

| ||||

23 |

A; 0.4 equiv. dbu, 35 °C, 8.0 h | >98 | 72 | 95:5 |

| B; 0.15 equiv. LiOtBu, 22 °C, 24 h | >98 | 19 | nd | |

| C; 0.13 equiv. NaOtBu, −30 °C, 24 h | >98 | <2 | na | |

|

| ||||

24 |

A; 1.4 equiv. dbu, 22 °C, 14 h | >98 | 70 | 88.5:11.5 |

| B; 1.15 equiv. LiOtBu, 22 °C, 24 h | >98 | <10 | nd | |

| C; 1.13 equiv. NaOtBu, −30 °C, 24 h | >98 | 22 | nd | |

Conditions: i) HO(CH2)2OH, 10 mol % pTsOH•H2O, tol., reflux, 12 h; 90% yield. ii) 3.0 equiv. tBuLi, thf, −78 °C; geranial, −78 °C, 2.0 h. iii) 1.0 mol % (n-Pr)4NRuO4, N-methylmorpholine N-oxide, CH2Cl2, 22 °C, 2.0 h. iv) 10 mol % pTsOH, acetone, 22 °C, 10 min.; 63% overall yield for three steps. v) NaClO2, NaH2PO4•H2O, tBuOH, H2O, 2-methyl-2-butene, 22 °C, 3.0 h; 82% yield. Reactions were performed under N2 atmosphere.

Determined by analysis of 400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures (±2%).

Yields of isolated and purified products (±5%).

Determined by GC analysis (±2%). See the Supporting Information for details.

|

(1) |

Investigations regarding the elucidation of mechanistic details of the NHC-catalyzed reactions are in progress and will be reported shortly.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial support was provided by the NIH (GM-57212) and the NSF (CHE-1111074). We thank H. Wu, K. P. McGrath and Dr. F. Haeffner for helpful discussions and Frontier Scientific, Inc. for gifts of B2(pin)2.

Dedicated to the memory of Professor Harry H. Wasserman

References

- 1.Hall DG, editor. Boronic Acids. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review on Rh-catalyzed enantioselective hydroboration reactions, see: Carroll AM, O’Sullivan TP, Guiry PJ. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:609–631.

- 3.Pelz NF, Woodward AR, Burks HE, Sieber JD, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16328–16329. doi: 10.1021/ja044167u.Burks HE, Kliman LT, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9134–9135. doi: 10.1021/ja809610h.Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13210–13211. doi: 10.1021/ja9047762.Schuster CH, Li B, Morken JP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:7906–7909. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102404.Kliman LT, Mlynarski SN, Ferris GE, Morken JP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:521–524. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105716.For an overview, see: Takaya J, Iwasawa N. ACS Catal. 2012;2:1993–2006.

- 4.a) Lee Y, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3160–3161. doi: 10.1021/ja809382c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee Y, Jang H, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18234–18235. doi: 10.1021/ja9089928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Meng F, Jang H, Hoveyda AH. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:3204–3214. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JE, Yun J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:145–147. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703699.Sim HS, Feng X, Yun J. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:1939–1943. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802150.Feng X, Yun J. Chem Commun. 2009:6577–6579. doi: 10.1039/b914207j.Park JK, Lackey HH, Rexford MD, Kovnir K, Shatruk M, McQuade DT. Org Lett. 2010;12:5008–5011. doi: 10.1021/ol1021756.Moure AL, Arrayás RG, Carretero JC. Chem Commun. 2011;47:6701–6703. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11949d.Lee JCH, McDonald R, Hall DG. Nat Chem. 2011;3:894–899. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1150.Kobayashi S, Xu P, Endo T, Ueno M, Kitanosono T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:12763–12766. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207343.For a review regarding the significance of enantioselective conjugate additions with B- and Si-based nucleophiles, see: Hartmann E, Vyas DJ, Oestreich M. Chem Commun. 2011;47:7917–7932. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10528k.

- 6.a) Ito H, Ito S, Sasaki Y, Matsuura K, Sawamura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14856–14857. doi: 10.1021/ja076634o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Guzman-Martinez A, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10634–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja104254d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ito H, Okura T, Matsuura K, Sawamura M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:560–563. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ito H, Kunii S, Sawamura M. Nat Chem. 2010;2:972–976. doi: 10.1038/nchem.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Park JK, Lackey HH, Ondrusek BA, McQuade DT. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2410–2413. doi: 10.1021/ja1112518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Park JK, McQuade DT. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:2717–2721. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Beenen M, An C, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6910–6911. doi: 10.1021/ja800829y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sole C, Gulyás H, Fernández E. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3769–3771. doi: 10.1039/c2cc00020b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang SS, Zhao YS, Tian P, Lin GQ. Synlett. 2013;24:437–442. [Google Scholar]; d) Hong K, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9252–9254. doi: 10.1021/ja402569j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For initial development of NHC-catalyzed BCA reactions, see: Lee K-s, Zhugralin AR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7253–7255. doi: 10.1021/ja902889s.Lee Ks, Zhugralin AR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12766.For enantioselective variants, see: Bonet A, Gulyás H, Fernández E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5130–5134. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001198.Wu H, Radomkit S, O’Brien JM, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8277–8285. doi: 10.1021/ja302929d.For related NHC-catalyzed silyl conjugate additions, see: O’Brien JM, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7712–7715. doi: 10.1021/ja203031a.

- 9.For a review on NHC-catalyzed processes in chemical synthesis, see: Enders D, Niemeier O, Henseler A. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5606–5655. doi: 10.1021/cr068372z.

- 10.Christoffers J, Baro A. Quaternary Stereocenters: Challenges and Solutions for Organic Synthesis. Wiley–VCH; Weinheim: 2006. For a comprehensive review regarding enantioselective synthesis of quaternary carbon stereogenic centers within acyclic molecules, see: Das JP, Marek I. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4593–4623. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05222a.

- 11.For synthesis of enantiomerically enriched compounds bearing a B-substituted quaternary carbon stereogenic center through the use of enantiomerically pure reagents (i.e., non-catalytic), see: Sonawane RP, Jheengut V, Rabalakos C, Larouche-Gauthier R, Scott HK, Aggarwal VK. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:3760–3763. doi: 10.1002/anie.201008067. and references cited therein.

- 12.Chen IH, Yin L, Itano W, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11664–11665. doi: 10.1021/ja9045839.O’Brien JM, Lee K-s, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10630–10633. doi: 10.1021/ja104777u.Chen IH, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Org Lett. 2010;12:4098–4101. doi: 10.1021/ol101691p.Feng X, Yun J. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:13609–13612. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002361.e) For examples (two) involving acyclic trisubstituted enones, see Ref. 5g.

- 13.For synthesis of C1-symmetric chiral imidazolinium salts and structural attributes critical to their ability to serve as effective ligands and/or catalysts, see: Lee K-s, Hoveyda AH. J Org Chem. 2009;74:4455–4462. doi: 10.1021/jo900589x.

- 14.Whereas 3c is obtained in four steps and 23% overall yield, the o-[2,4,6-(i-Pr)3]phenyl derivative is synthesized in ca. 5% overall yield.

- 15.Cyclic enones were prepared by a one-vessel process with inexpensive and commercially available starting materials. See: Stork G, Danheiser RL. J Org Chem. 1973;38:1775–1776.Moritani Y, Appella DH, Jurkauskas V, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6797–6798.

- 16.a) Kim HR, Jung IG, Yoo K, Jang K, Lee ES, Yun J, Son SU. Chem Commun. 2010;46:758–760. doi: 10.1039/b919515g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jang H, Zhugralin AR, Lee Y, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7859–7871. doi: 10.1021/ja2007643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Semba K, Fujihara T, Terao J, Tsuji Y. Chem Eur J. 2013;18:4179–4184. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Moure AL, Arrayás RG, Cardenas DJ, Alonso I, Carretero JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7219–7222. doi: 10.1021/ja300627s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Park JK, Ondrusek BA, McQuade DT. Org Lett. 2012;14:4790–4793. doi: 10.1021/ol302086v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Jung B, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1490–1493. doi: 10.1021/ja211269w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yuan W, Ma S. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:1867–1872. [Google Scholar]; c) Meng F, Jung B, Haeffner F, Hoveyda AH. Org Lett. 2013;15:1414–1417. doi: 10.1021/ol4004178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Meng F, Jang H, Jung B, Hoveyda BAH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:5046–5051. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acyclic β,β-disubstituted enones can be prepared efficiently and with >98% E selectivity by Zr-catalyzed carboalumination of terminal alkynes followed by workup with acetyl chloride. See: Negishi E-i, Kondakov DY, Choueiry D, Kasai K, Takahashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9577–9588.Wipf P, Lim S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1993;32:1068–1071.

- 19.As with the cyclic substrates (Ref. 14), 2a is more easily prepared than the more sizeable derivative needed to obtain maximum enantioselectivity with disubstituted acyclic enones or enals.

- 20.Liskin DV, Valente EJ. J Mol Structure. 2008;878:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Analysis of the unpurified product mixture indicates that the lower yield at 70 °C is due to adventitious retro-aldol processes.

- 22.Lago JHG, Ramos CS, Casanova DCC, Morandim AA, Bergamo DCB, Cavalheiro AJ, Bolzani VS, Furlan M, Guimãraes EF, Young MCM, Kato MJ. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1783–1788. doi: 10.1021/np030530j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Applications of Cu-catalyzed BCA to natural product synthesis are uncommon, and, as far as we are aware, there are no cases involving Lewis base-catalyzed processes. For an application of a non-enantioselective NHC–Cu-catalyzed BCA, see: Marcus AP, Sarpong R. Org Lett. 2010;12:4560–4563. doi: 10.1021/ol1018536.For use of phosphine–Cu-catalyzed enantioselective BCA, see: Chea H, Sim HS, Yun J. Adv Synth Catal. 2009;351:855–858.Stavber G, Casar Z. Appl Organometal Chem. 2013;27:159–165.

- 24.For a review on Cu-catalyzed ketone aldol processes, see: Shibasaki M, Kanai M. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2853–2873. doi: 10.1021/cr078340r.For an alternative Cu-catalyzed approach to generating ketone-aldol products, see Ref. 18d.

- 25.NHC–Cu–B(pin) complexes readily add to aldehydes; see: Laitar DS, Tsui EY, Sadighi JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11036–11037. doi: 10.1021/ja064019z.b) Ref. 8d.

- 26.Chakor JN, Merlini L, Dallavalle S. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:6300–6307. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.