Summary

The immunoregulatory role of human donor bone marrow cells (DBMC) has been studied extensively in our laboratory using in vitro and ex vivo assays. However, new experimental systems that can overcome the limitations of tissue culture assays but with more clinical relevance than purely animal experimentation, needed to be generated. Therefore we have developed a new human peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse islet transplantation model without the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and have used it to evaluate the tolerogenic effects of DBMC. Nonobese diabetogenic (NOD)–SCID mice were transplanted with human deceased donor islets and were reconstituted with human PBL (allogeneic to islets; denoted as recipient) with or without DBMC from the islet donor.

It was observed that the most cellularly economical dose was 3000 islets per animal and that injection into the portal vein was better than implantation under the kidney capsule. Even though maximal lymphoid reconstitution was observed with 40-million fresh and anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL (conventional method), the mice developed severe graft GvHD. However, with the new method of reconstitution where animals were injected with 20-million anti-CD3-activated plus 40-million anti– donor-activated recipient PBL, no discernible GvHD was observed. More importantly, this latter method was associated with islet transplant rejection, which in turn could be abrogated by co-injection of the animals with DBMC. These in vivo results confirmed our previous in vitro observations that human DBMC have regulatory activity.

Keywords: SCID, Human islet model, Bone marrow, Transplantation, Tolerance

Introduction

Hematopoietic chimerism, established during the fetal or newborn period, has been synonymous with a state of lifelong unresponsiveness to donor alloantigens [1]. However, even though this chimerism has also been extensively studied in adult animals and human beings [2– 8] there is vigorous controversy with regard to the role and the extent of chimerism needed to achieve organ transplant acceptance in human beings. It has been unclear whether microchimerism induces allograft acceptance or whether it is only an epiphenomenon resulting from the transplantation of a vascularized organ [9,10]. In some reports, microchimerism mediated by means of blood transfusions, organ transplantation, or pregnancy has even been associated with allo-sensitization and allograft rejection [11–13]. Recently we have obtained some evidence linking increasing chimerism in the bone marrow compartment following donor bone marrow cell (DBMC) infusions with graft survival in renal transplant recipients as well as ex vivo evidence of donor-specific unresponsiveness [14 –16].

Despite these in vivo and in vitro observations, the immune regulatory mechanisms mediated by DBMC have not been fully understood, especially in human beings. This has primarily resulted from the limitations on one hand of in vitro culture systems, and on the other that certain experimental procedures cannot be carried out in human beings. In addition, even though studies in animal (mostly rodent) models of transplantation have greatly helped, major differences between the animal and human immune systems have limited their clinical value. In this report we describe the development of a SCID mouse experimental islet transplant model that may confer the benefits of both human and animal systems in studying the potential of human DBMC to prolong human allograft survival.

Subjects and methods

Animal subjects

All animal experiments were performed with the approval from the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC). Nonobese diabetogenic, severe combined immunodeficient (NOD-SCID) mice (which do not spontaneously develop diabetes), 3– 4 weeks of age, were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (catalog no. 001303) and were housed in a virus-antigen-free facility. They were first tested for “leakiness,” i.e., the presence of mouse immunoglobulins (Ig) using a sandwich enzyme-linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The mice that had <1 μg/ml Ig were used. The various experimental groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental groups and treatment.

| Group | Day 0 | Day 3 (IP) | Days 5 and 7 (IP) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 20 × 106 Recipient fresh PBL (IP) | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL activated with anti-CD3 for 3 days | None | Good reconstitution but severe GvHD |

| II | 20 × 106 Recipient fresh PBL (IP) | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL co-cultured with 20 × 106 donor irradiated spleen cells for 5 or 7 days | None | Good reconstitution but severe GvHD |

| III | None | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL activated with anti-CD3 for 3 days | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL co-cultured with 30 × 106 donor irradiated spleen cells for 5 or 7 days | Optimal reconstitution without GvHD |

| IV | 3000 Human islets (portal)* | PBS | PBS | Islet survival (negative control) |

| V | 3000 Human islets (portal)* | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL activated with anti-CD3 and co-cultured with 10 × 106 donor irradiated spleen cells for 3 days | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL co-cultured with 30×106 donor irradiated spleen cells for 5 or 7 days | Islet rejection (positive control) |

| VI | 3000 Human islets (portal)* | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL activated with anti-CD3 and co-cultured with 10 × 106 NT-LP/DBMC for 3 days | 20 × 106 Recipient PBL co-cultured with 20 × 106 donor irradiated spleen cells + 10 × 106 NT-LP/DBMC for 5 or 7 days | Graft prolongation (experimental) |

Experiment 1: Islet and Bone Marrow Donor (D) = HLA-A3, A11; B7, B8; DR15, DR17.

Recipient Responder (R) = HLA-A1, A10; B8, B18; DR3, DR15.

Experiment 2: Islet and Bone Marrow Donor (D) = HLA-A2, A32; B51, B70; DR4, DR7.

Recipient Responder (R) = HLA-A1, A34; B12, B44; DR7, DR–.

Experiment 3: Islet and Bone Marrow Donor (D) = HLA-A2, A–; B8, B60; DR7, DR17.

Recipient Responder (R) = HLA-A3, A24; B13, B18; DR7, DR–.

Following is donor–recipient information on the islet transplant survival experiments performed in groups IV, V, and VI (results of experiment 2 are shown in Figure 5). The recipient in these experiments denotes normal laboratory volunteer responder PBL that were used to reconstitute SCID mice.

Implantation of human islet cells

Purified human pancreatic islets of Langerhans were obtained through the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) Human Islet Distribution Program or from the Diabetes Research Institute, University of Miami. All deceased donor tissues were used after obtaining signed informed consents that were approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards. The mice were anesthetized with Isofluorane inhalation and the portal vein was accessed through a 2-cm incision in the abdomen. Varying numbers of human deceased donor islets were injected, using a 26-gauge needle, into the portal vein on day 0 as indicated, and the bleeding was stopped by compression. Alternately, the islets were implanted under the kidney capsule. The surgical wound was sutured with 6.0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). Care was taken to keep the animals warm during the surgical procedures and the recovery period, and the animals were given buprenorphine as analgesic for 2–5 days.

Human leukocyte preparation and reconstitution

A 300–450-ml quantity of peripheral blood were obtained on day 0 from healthy laboratory volunteers, having at least one HLA-DR antigen in common with the islet (and DBMC) donor, analogous to the minimum histocompatibility matching requirement for many series of renal transplants performed at this center [14 –18]. All had signed informed consents approved by our center Institutional Review Board and consistent with HIPPA privacy regulations. Leukocytes (PBL) were prepared by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation and were then cultured for indicated lengths of time with either mitogenic anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) or irradiated spleen cells from the same deceased donor as the islets (and DBMC) with or without half the number of DBMC (or irradiated spleen cells as controls). These PBL, designated as recipient cells, were injected intraperitoneally into NOD-SCID mice on days 0, 3, 5, and 7 as indicated.

Preparation and infusion of donor bone marrow cells

Vertebral body bone marrow cells were isolated from the deceased islet donors [19] followed by ficollhypaque gradient centrifugation [20]. As described elsewhere, the CD3+ T cells, CD15+ monocytegranulocyte precursors and glycophorin-A+ red cell precursors were then depleted with monoclonal antibodies coupled to magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) to obtain a population of cells that we have designated as non–T lymphoid precursor DBMC (NT-LP/DBMC) [20 –23]. These NT-LP/DBMC were co-cultured with twice the number of recipient PBL plus twice the number of donor irradiated spleen cells for 3–7 days, and these preparations were injected into the mice as described above. This was compared with co-cultures of recipient PBL and irradiated donor spleen cells. Previously, we had shown that both irradiated spleen cells and T-cell–depleted nonirradiated spleen cells were equivalently nonregulatory in MLR responses [20].

Reconstitution monitoring

Blood (100 μl) was drawn at bi-weekly intervals from the tail vein of the reconstituted (and control) mice into microtubes containing 10 ul of ACD anti-coagulant solution. The cells were tested by four-color flow cytometric analysis as previously described [20 –24] to identify and characterize the reconstituted cells for human CD markers, after gating out the mouse cells using mouse anti-CD45 antibodies (Figure 1, IIIA). The separated plasma was used for measurement of the level of human immunoglobulins (Ig) by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) and human C-peptide by radioimmunoassay (RIA) as described below.

Figure 1.

Reconstitution of NOD-SCID Mice with human PBL (n = 4/group). NOD-SCID mice were injected according to the following schedule in various groups: (Group I) on day 0 with 20 × 106 fresh recipient PBL, and on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL, (Group II) on day 0 with 20 × 106 fresh, and on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti– donor-activated recipient PBL, and (Group III) on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL and on days 5 and 7 each with 20 × 106 anti– donor-activated recipient PBL. On indicated days, tail vein blood was obtained from the mice and flow cytometric analysis was performed for the indicated phenotypes gated on total leukocytes based on forward versus side scatter. The standard deviations (SD; not shown) were less than 10%. A representative experiment for one of the mice on day 21 in group III is shown in histograms IIIA-IIIF so as to further depict the characteristics of the human cells that were gated (IIIA) on those that did not bind by mouse CD45-FITC.

Sandwich ELISA

ELISA plates were coated with optimal concentrations of affinity purified rabbit anti-mouse IgG + IgM or affinity purified anti-human IgG + IgM as needed. After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween-20, appropriate wells were incubated with the test serum or plasma samples or known concentrations of affinity purified human or mouse Igs (as standards) appropriately diluted in 1% BSA–PBS– 0.05% Tween-20. Subsequently, the plates were incubated with optimal concentrations of peroxidase-conjugated and affinity-purified rabbit anti-human or anti-mouse IgG + IgM in 1% BSA–PBS– 0.05% Tween-20. (All antibodies and standards were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA. The anti-human antibodies had minimal cross-reactivity with mouse serum proteins and the anti-mouse antibodies had minimal cross-reactivity with human serum proteins). The plates were washed four times with PBS-0.05% Tween-20 after each step. Finally, the plates were incubated with TMB substrate solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 15 minutes, the color reaction was stopped with 0.5 mol/l H2SO4 and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The amount of human or mouse Igs were measured in the samples using standard curves.

C-peptide assay for monitoring islet cell function

The survival of the transplanted human islets was monitored by estimating the level of human C-peptide in plasma using a competitive human C-peptide specific radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit following the instructions of the manufacturers (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO). The RIA kit did not have cross-reactivity with mouse C-peptides as determined by normal mouse serum internal controls. The animals were fasted overnight and were then intravenously administered 2 g glucose per kilogram of body weight 30 minutes before the bleeding (see above) to determine the maximal islet graft function.

Detection of GvHD

Development of GvHD was characterized by ruffled fur, loss of appetite (quantitated as the amount of food consumed by an experimental or control group of five mice per cage per week), diarrhea, weight loss and in severe cases, death. In some cases the level of GvHD was measured using the spleen/body weight ratios of reconstituted mice versus those of age matched control mice [25].

Statistical analysis

For statistical validity, four to five animals per group were used in each experiment. Many experiments were then independently repeated three times or more with different sets of human islets and responder recipient cells. However, for the sake of simplicity, representative data from only one of these sets (per experiment) are shown in the figures. Even though there were variations between assays, especially where human islets were transplanted, the variations within a group of replicate mice were less than 10%. Since the data showed parametric distribution, the results were compared among groups for statistically significant differences using paired or unpaired Student T test as appropriate.

Results

Reconstitution of NOD-SCID mice with human PBL

The majority of the human PBL that survived and propagated in the NOD-SCID mice were CD3+ CD45RO+ activated or memory T cells distributed into CD4 and CD8 subsets (Figure 1). Higher reconstitution was observed in Group I mice that were injected on day 0 with 20 × 106 fresh PBL and then on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti-CD3 activated PBL, and in Group II mice injected on day 0 with 20 × 106 fresh PBL and then on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti– donor-activated PBL. However, progressively severe GvHD was observed from the third week onward (data not shown) so that the animals had to be sacrificed by 40 – 60 days for humane reasons. This increase in GvHD appeared to be associated with the rapid increase in the proportion of human T cells (Figure 1). Conversely, group III mice which were injected on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti-CD3-activated PBL and then on days 5 and 7 each with 20 × 106 anti– donor-activated PBL, showed somewhat lower but significant levels of reconstitution (Figure 1), and only a minority of the mice developed mild GvHD (indicated by lesser gain in body weight than nonreconstituted control mice) by day 55 (day of sacrifice; data not shown). Therefore, for all subsequent experiments (Figure 4 onward) the reconstitution of mice with human PBL was performed as described in group III. No human CD14+ monocytes or CD19+ B cells were found in the peripheral venous blood (Figure 1, IIIF), despite finding significant levels of human immunoglobulins in plasma (see below).

Figure 4.

Rejection of human islets transplanted into NOD-SCID mice in the presence of anti-donor human PBL. NOD-SCID mice were (Group IV) transplanted with 3000 human islets on day 0, (Group V) transplanted with 3000 human islets on day 0 and then reconstituted on day 3 with 20 ×106 anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL, then on days 5 and 7 each with 20 ×106 recipient PBL activated with donor irradiated spleen cells, and (Group III) reconstituted on day 3 with 20 ×106 anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL, then on days 5 and 7 each with 20 ×106 recipient PBL activated with donor irradiated spleen cells (without islet transplantation). The plasma samples were collected on indicated days and the levels of secreted human C-peptide were estimated by a competitive RIA. The data are shown as mean ± SD with four animals in each group.

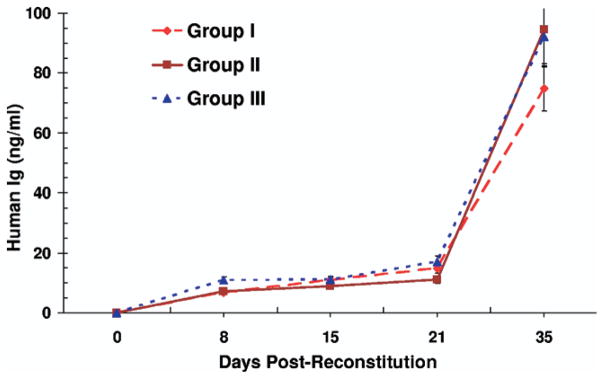

Increasing concentrations of human Igs in plasma ranging from 8 ng/ml on day 8 to 100 ng/ml on day 35 were observed with no statistically significant differences among the three groups of mice (Figure 2). Control animals that were not reconstituted with human cells did not have any cells that were bound by anti-human CD monoclonal antibodies nor did they have any human immunoglobulins detected by ELISA (data not shown), thus indicating the absence of nonspecific reactions.

Figure 2.

Human Immunoglobulin production in NOD-SCID mice reconstituted with human PBL: NOD-SCID mice were injected according to the following schedule in various groups: (Group I) on day 0 with 20 × 106 fresh and on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL, (Group II) on day 0 with 20 × 106 fresh and on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti– donor-activated recipient PBL, and (Group III) on day 3 with 20 × 106 anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL and on days 5 and 7 each with 20 × 106 anti– donor-activated recipient PBL, as in Figure 1. The plasma collected from the venous blood from the three groups of mice on the indicated days was used to estimate the level of human immunoglobulins (Ig) by a sandwich ELISA. The data are shown as mean ± SD with four animals in each group.

Acceptance of purified human islet cell transplants by NOD-SCID mice

In preliminary observations, NOD-SCID mice were transplanted with varying numbers of purified human islets into the portal vein or under the kidney capsule and the level of human C-peptide was monitored in the plasma of the mice at biweekly intervals. Maximal C-peptide production was observed 2– 4 weeks post-transplantation (Figure 3). Three thousand islet cells transplanted into the liver through the portal vein produced significant levels of human C-peptide, even though the highest levels were observed with 6000 islet cells. In addition, higher human C-peptide secretions were observed with islets transplanted into the portal vein than those transplanted under the kidney capsule (Figure 3). Therefore, for the sake of cellular economy with reproducible results, 3000 human islet cells per mouse were injected into the portal vein in subsequent experiments, as the number of purified islet cells available for each experiment was a limiting factor. Aside from monitoring the levels of human C-peptide, attempts were also made to perform immunohistologic examinations. Although islets could be visualized with certainty only when injected under the kidney capsule (data not shown), no further groups using this procedure were tested because of the greater efficiency of the portal vein technique.

Figure 3.

Survival of human islets in NOD-SCID mice. Indicated numbers of purified human islet equivalents were transplanted into the portal vein or under the kidney capsule of NOD-SCID mice. C-peptide levels were monitored in serial plasma samples at weekly intervals as indicated using a human C-peptide RIA kit. The data are shown as mean ± SD with five animals in each group.

Rejection of islet transplants by reconstituted recipient PBL

NOD-SCID mice were injected into the portal vein with 3000 human islets on day 0 and were then reconstituted with human recipient PBL (allogeneic to the islet donor) by intra-peritoneal injection of anti-CD3 activated PBL on day 3, and anti– donor-activated PBL each on days 5 and 7 (Table 1). In the control mice without human lymphocyte reconstitution the production of human C-peptide was found to peak on day 28 and then gradually declined (Figure 4, group IV). Compared with this, the level of C-peptide was significantly lower (p <0.01) in mice that were also reconstituted with anti-CD3 and anti– donor-activated PBL, thus indicating that the islets were likely being rejected (Figure 4, group V). The shape of the curve further indicated that the rejection was gradual initially but was complete by day 42, when no human C-peptide could be detected.

Prolongation of islet graft survival by bone marrow cells

NOD-SCID mice underwent transplantion with human islets on day 0 and were then reconstituted with human recipient PBL as above. In the control mice, with no recipient reconstitution (group IV), the transplanted human islets continued to function (for a somewhat longer period of time than in the previous experiments) (Figure 5). In contrast, the level of C-peptide was significantly lower (p <0.01) in mice that were also reconstituted with anti-CD3 and anti– donor-activated recipient PBL (group V), thus indicating a rejection process. However, co-culture and co-injection of NT-LP/DBMC together with the recipient PBL (that were also stimulated with equal number of donor irradiated spleen cells) abrogated this rejection as shown by the increased human C-peptide levels in group VI when compared with group V (p <0.01). These were consistent with the notion that NT-LP/DBMC could protect the transplanted human islets from rejection mediated by the alloreactive responses of the reconstituted recipient PBL.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of human islet transplant rejection by NT-LP/DBMC in NOD-SCID mice. NOD-SCID mice were divided into three groups: (1) Group IV, negative control group, transplanted intraportally with 3000 human islets on day 0 and then injected with PBS only and therefore had no reconstitution; (2) Group V, positive control group, transplanted intraportally with 3000 human islets on day 0 and then reconstituted by injection on day 3 with 20 ×106 recipient PBL activated with anti-CD3 and co-cultured with 10 ×106 donor irradiated spleen cells for 3 days, followed, on days 5 and 7, with 20 ×106 recipient PBL co-cultured with 30 ×106 donor irradiated spleen cells for 5 or 7 days; and (3) Group VI, experimental group, transplanted intraportally with 3000 human islets on day 0 and then reconstituted by injecting on day 3 with 20 ×106 recipient PBL activated with anti-CD3 and co-cultured with 10 ×106 NT-LP/DBMC for 3 days, followed by on days 5 and 7 each with 20 ×106 recipient PBL co-cultured with 20 ×106 donor irradiated spleen cells plus 10 ×106 NT-LP/DBMC for 5 or 7 days. Then, plasma samples were collected on indicated days and the levels of secreted human C-peptide levels were measured by a competitive RIA. The data are shown as mean ±SD with five animals in each group.

Discussion

The discovery of the SCID mouse and the dual observations that this mouse accepts an allo- or xenogeneic immune system and allo- or xenogeneic organ or tissue grafts without rejection, opened new perspectives in the study of transplant immunology [26 –36]. Indeed, a mature human immune system can be introduced into these mice achieving, depending on the induction protocol, variable levels of reconstitution [26,27,36]. To be useful, however, the human immune cells in these chimeras must recirculate and be able to reject the allo- or xenografts while leaving the mouse host unaffected. Many reports have appeared on the human peripheral blood leukocyte reconstituted SCID (hu-PBL-SCID) mouse as a model for the study of transplantation immunobiology [26 –36]. However, very few of these studies have been able to avoid the development of xenogeneic GvHD consequent to the human PBL reconstitution, thus limiting their usefulness to short term immune assays. We have overcome this limitation by the use of human PBL that are pre-activated with donor irradiated cells for the reconstitution of the NOD-SCID mice instead of naïve cells which were reported to be the cause of GvH [37–39]. Although such an experimental system can be used for a number of applications including studies on the islet metabolism, graft rejection and tolerance induction protocols, our own studies were geared towards the evaluation of immune regulation by donor bone marrow cell infusions.

The general optimized scheme consisted of NOD-SCID mice (i) being transplanted intraportally on day 0 with purified human islets from deceased donors, and (ii) then injected intraperitoneally on days 3, 5, and 7 with human PBL from laboratory volunteers (allogeneic to the islets; denoted as recipient) that had been co-cultured with T-cell– depleted bone marrow cells (NT-LP/DBMC) and/or irradiated spleen cells from the islet donor (Table 1). The combination with NT-LP/DBMC was found to be effective in bringing about the prolongation of survival of the transplanted islets that would otherwise be rejected by the reconstituted allogeneic recipient PBL in this NOD-SCID system.

The C-peptide production was directly proportional to the number of islets transplanted. However, for the sake of cellular economy as the number of purified islet cells was a limiting factor, 3000 human islet cells were transplanted intraportally per mouse. This dose of human islets was found to give reproducible results and was similar to that used by others in similar experimental models [34,35]. However, it should be mentioned that there was variability in the length of survival and amount of C-peptide produced by the human islets from lot to lot (compare Figures 3, 4, and 5). This appeared to be primarily because of the differences in the quality, purity and viability of human islets available for research. Variability in the number of islets transplanted might not a contributing factor as the islets used in Figures 4 and 5 were prepared and counted in equivalent fashion by the same center (Diabetes Research Institute at the University of Miami). Another potential source of variability between different sets of experiments could be the source of PBL used for the reconstitution of the mice; this, however, appeared to be relatively minor as evidenced by the variations of less than 25% in the cellular make-up between the experiments with PBL from different blood donors (data not shown). However, this variability could be countered to some extent by an internal control (in each experiment), in which islets are transplanted alone without additional treatment.

The optimal inoculum consisted of anti-CD3 activated recipient PBL on day 3 followed by recipient PBL activated with donor irradiated spleen cells on days 5 and 7. The use of anti-CD3 activated PBL, a conventional method for hu-PBL SCID development [28,34,35] was needed in the present model for an enhanced reconstitution (data not shown). This was also accompanied by an increased incidence of GvHD. However, subsequent injection of recipient PBL activated with irradiated spleen cells from the islet donor abrogated this GvHD by an as yet unknown mechanism. Flow cytometric analysis performed with the peripheral blood of the reconstituted NOD-SCID mice showed that the majority of the circulating human CD45+ cells were CD45RO+/CD3+ memory T cells distributed into CD4 and CD8 sub-populations (Figure 1). Unlike in normal human PBL, however, the proportion of CD8+ cells was higher than that of the CD4+ cells in the reconstituted mice (Figure 1). Additionally, the reconstituted mice did not have appreciable amounts of circulating human CD19+ B cells, CD14+ monocytes (Figure 1, IIIF) or CD56+ NK cells (not shown). However, increasing concentrations of human IgG ranging from 8.0ng/ml on day 8 to 100ng/ml on day 56 were observed in human PBL reconstituted mice (Figure 2) speculatively produced by human B lineage cells likely sequestered in the secondary lymphoid tissues.

It might be argued that sub-clinical xenoreactive GvH reactions could have contributed to islet rejection since liver is a major GvHD target and islets were transplanted into the portal vein. Even though we have not completely ruled out this possibility, it is highly unlikely as similar pattern of islet survival was observed in both the negative controls (group IV) without reconstitution and the experimental (group VI) animals with DBMC (Figure 5).

The rationale for co-culturing NT-LP/DBMC with the recipient responders, during these experiments, was derived from our in vitro observations that DBMC mediated their regulatory activity during an early period (first two days) of the effector cell generation stage and that DBMC could not inhibit already activated allogeneic responder cells [16,20]. Similarly, we had previously observed that both T-cell–depleted and irradiated donor spleen cells could be used as negative modulator controls in vitro with equivalent results [20]. Therefore, in these initial experiments described here we used the addition of irradiated spleen cells as controls for NT-LP/DBMC. Extrapolation of our earlier in vitro and ex vivo studies to the current experimental model would suggest that the DBMC mediated inhibition could be quasi-antigen specific and dose-dependent. Thus, at higher cell concentrations the inhibition would be nonspecific and would disappear with decreasing number of tolerogenic DBMC, while the donor specific inhibition would remain statistically significant [14,18,20]. It would also appear that bone marrow cells autologous or syngeneic to the responding recipient could function as regulatory cells [23,40]. However, such analyses in the current experimental setting were logistically difficult as islets, vertebral body bone marrow and spleen from multiple deceased donors would be required simultaneously.

The co-culture and co-injection of NT-LP/DBMC together with the recipient PBL abrogated the rejection process, thus indicating the tolerogenic effects of the donor bone marrow cells in this model (Figure 5). In contrast, however, a recent clinical trial from our group indicated that combined islet and hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) allotransplantation using an “Edmonton-like” immunosuppression, without ablative conditioning, did not lead to stable peripheral chimerism and graft tolerance [41]. This could be caused by a number of factors, including the possible presence of residual anti-islet autoimmunity that could not be abrogated by the HSC or the failure to attain stable chimerism resulting from suboptimal treatment regimen in the type-1 diabetic patients.

In summary, we have developed a new hu-PBL-SCID–islet transplant model without the occurrence of discernible GvHD that had plagued earlier hu-PBL-SCID models. This was done by a novel approach for reconstitution by the use of preactivated human PBL whose responses would be directed against human alloantigens, instead of naïve cells that would primarily react to the xenogeneic antigens of the mice. Using this model, we have shown that simultaneous co-injection of the hu-PBL-SCID mice with donor bone marrow cells prolonged the survival of human islet grafts (Figure 5), thus confirming our previous in vitro observations that DBMC have an immunoregulatory role [14–16, 20–24]. This experimental system might enable us to make an in-depth study of the mechanism of the tolerogenic effects mediated by DBMC in a clinically relevant manner while at least partially overcoming the limitations of in vitro culture systems. For the transplant community, it could create new possibilities for studies on islet metabolism, graft rejection and tolerance induction in a clinically relevant in vivo experimental model.

Acknowledgments

Some of the human islets were obtained through JDRFI Human Islet Distribution Program. We thank Ms. Silvia Alvarez and Ms. Teresa Vallone for excellent technical help, and Ms. Aisha Khan, Ms. Julie Allickson and the other members of the Cell Transplant Center for the islet and bone marrow preparations.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DBMC

donor bone marrow cells

- GvHD

graft-vs-host disease

- NOD

nonobese diabetogenic

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficient

References

- 1.Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar PB. Actively acquired tolerance of foreign cells. Nature. 1953;172:603. doi: 10.1038/172603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber WH, Mankin JA, Laskow DA, Deierhoi MH, Julian BA, Curtis JJ, Diethelm AG. Long-term results of a controlled prospective study with transfusion of donor-specific bone marrow in 57 cadaveric renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1991;51:70. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199101000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caridis DT, Liegeois A, Barrett I, Monaco AP. Enhanced survival of canine renal allografts of ALS-treated dogs given bone marrow. Transplant Proc. 1973;5:671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monaco AP, Clark AW, Wood ML, Sahyoun AI, Codish SD, Brown RW. Possible active enhancement of a human cadaver renal allograft with antilymphocyte serum (ALS) and donor bone marrow: Case report of an initial attempt. Surgery. 1976;79:384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvatierra O, Jr, Vincenti F, Amend W, Potter D, Iwaki Y, Opelz G, et al. Deliberate donor-specific blood transfusions prior to living related renal transplantation. A new approach. Ann Surg. 1980;192:543. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198010000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharabi Y, Sachs DH. Mixed chimerism and permanent specific transplantation tolerance induced by a nonlethal preparative regimen. J Exp Med. 1989;169:493. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slavin S, Strober S, Fuks Z, Kaplan HS. Long-term survival of skin allografts in mice treated with fractionated total lymphoid irradiation. Science. 1976;193:1252. doi: 10.1126/science.785599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starzl TE, Demetris AJ, Trucco M, Murase N, Ricordi C, Ildstad S, et al. Cell migration and chimerism after whole-organ transplantation: The basis of graft acceptance. Hepatology. 1993;17:1127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elwood ET, Larsen CP, Maurer DH, Routenberg KL, Neylan JF, Whelchel JD, O’Brien DP, Pearson TC. Microchimerism and rejection in clinical transplantation. Lancet. 1997;349:1358. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood K, Sachs DH. Chimerism and transplantation tolerance: Cause and effect. Immunology Today. 1996;17(12):584. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)10069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlitt HJ, Hundrieser J, Ringe B, Pichlmayr R. Donor-type microchimerism associated with graft rejection eight years after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:646. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivasai KS, Alevy YG, Duffy BF, Brennan DC, Singer GG, Shenoy S, et al. Peripheral blood microchimerism in human liver and renal transplant recipients: Rejection despite donor-specific chimerism [Published erratum appears in Transplantation 1997;64:1636] Transplantation. 1997;64:427. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199708150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SivaSai KS, Jendrisak M, Duffy BF, Phelan D, Ravenscraft M, Howard T, Mohanakumar T. Chimerism in peripheral blood of sensitized patients waiting for renal transplantation: Clinical implications. Transplantation. 2000;69:538. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathew JM, Garcia-Morales R, Fuller L, Rosen A, Ciancio G, Burke GW, et al. Donor bone marrow-derived chimeric cells present in renal transplant recipients infused with donor marrow. I. Potent regulators of recipient antidonor immune responses. Transplantation. 2000;70:1675. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200012270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathew JM, Miller J. Immunoregulatory role of chimerism in clinical organ transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:115. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathew JM, Garcia-Morales RO, Carreno M, Jin Y, Fuller L, Blomberg B, et al. Immune responses and their regulation by donor bone marrow cells in clinical organ transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2003;11:307. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(03)00056-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciancio G, Miller J, Garcia-Morales RO, Carreno M, Burke GW, 3rd, Roth D, et al. Six-year clinical effect of donor bone marrow infusions in renal transplant patients. Transplantation. 2001;71:827. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Morales R, Carreno M, Mathew J, Cirocco R, Zucker K, Ciancio G, et al. Continuing observations on the regulatory effects of donor-specific bone marrow cell infusions and chimerism in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1889;65:956. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontes PA, Ricordi C, Rao AS, Rybka WB, Dodso SF, Broznick B, et al. Human vertebral bodies as a source of bone marrow cell augmentation in whole organ allografts. In: Ricordi C, editor. Methods in Cell Transplantation. R.G. Landes; Austin: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathew JM, Carreno M, Fuller L, Ricordi C, Tzakis A, Esquenazi V, Miller J. Modulatory effects of human donor bone marrow cells on allogeneic cellular immune responses. Transplantation. 1997;63:686. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199703150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathew JM, Carreno M, Fuller L, Ricordi C, Kenyon N, Tzakis AG, et al. In vitro immunogenicity of cadaver donor bone marrow cells used for the induction of allograft acceptance in clinical transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:1172. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199910270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew JM, Fuller L, Carreno M, Garcia-Morales R, Burke GW, 3rd, Ricordi C, et al. Involvement of multiple subpopulations of human bone marrow cells in the regulation of allogeneic cellular immune responses. Transplantation. 2000;70:1752. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200012270-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathew JM, Carreno M, Fuller L, Burke GW, 3rd, Ciancio G, Ricordi C, et al. Regulation of alloimmune responses (GvH reactions) in vitro by autologous donor bone marrow cell preparation used in clinical organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:846. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathew JM, Carreno M, Zucker K, Fuller L, Kenyon N, Esquenazi V, et al. Cellular immune responses of human cadaver donor bone marrow cells and their susceptibility to commonly used immunosuppressive drugs in transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;65:947. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199804150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shearer G. Graft versus host disease. In: Colligan JE, et al., editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: Wiley Inter-science; 1991. Section 4.3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berney T, Molano RD, Pileggi A, Cattan P, Li H, Ricordi C, Inverardi L. Patterns of engraftment in different strains of immunodeficient mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Transplantation. 2001;72:133. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greiner DL, Shultz LD, Yates J, Appel MC, Perdrizet G, Hesselton RM, et al. Improved engraftment of human spleen cells in NOD/LtSz-scid/scid mice as compared with C. B-17-scid/scid mice. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gysemans C, Waer M, Laureys J, Depovere J, Pipeleers D, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. Islet xenograft destruction in the hu-PBL-severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse necessitates anti-CD3 preactivation of human immune cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamura T, Niguma T, Fechner JH, Jr, Wolber R, Beeskau MA, Hullett DA, Sollinger HW, Burlingham WJ. Chronic human skin graft rejection in severe combined immunodeficient mice engrafted with human PBL from an HLA-presensitized donor. Transplantation. 1992;53:659. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199203000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKenzie DA, Sollinger HW, Hullett DA. Acute graft rejection of human fetal pancreas allografts using donor-specific human peripheral blood lymphocytes in the SCID mouse. Transplantation. 1996;61:1461. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199605270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Shultz LD, Lieberman M, Weissman IL. The SCID-hu mouse: Murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science. 1988;241:1632. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB. Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature. 1988;335:256. doi: 10.1038/335256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray AG, Petzelbauer P, Hughes CC, Costa J, Askenase P, Pober JS. Human T-cell-mediated destruction of allogeneic dermal microvessels in a severe combined immunodeficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiroki R, Poindexter NJ, Woodle ES, Hussain MS, Mohanakumar T, Scharp DW. Human peripheral blood lymphocyte reconstituted severe combined immunodeficient (hu-PBL-SCID) mice. A model for human islet allograft rejection. Transplantation. 1994;57:1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiroki R, Nazirrudin B, Hoshinaga K, Naide Y, Scharp DW, Mohanakumar T. Human peripheral blood lymphocyte-reconstituted, severe combined immunodeficient mice as a model for porcine islet xenograft rejection in human beings. Artif Organs. 1996;20:878. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1996.tb04562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tary-Lehmann M, Saxon A, Lehmann PV. The human immune system in hu-PBL-SCID mice. Immunol Today. 1995;16:529. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson BE, McNiff J, Yan J, Doyle H, Mamula M, Shlomchik MJ, Shlomchik WD. Memory CD4+ T cells do not induce graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:101. doi: 10.1172/JCI17601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drobyski WR, Majewski D, Ozker K, Hanson G. Ex vivo anti-CD3 antibody-activated donor T cells have a reduced ability to cause lethal murine graft-versus-host disease but retain their ability to facilitate alloengraftment. J Immunol. 1998;161:2610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eguchi H, Knosalla C, Lan P, Cheng J, Diouf B, Wang L, et al. T cells from presensitized donors fail to cause graft-versus-host disease in a pig-to-mouse xenotransplantation model. Transplantation. 2004;78:1609. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000142621.52211.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burt RK, Marmont A, Oyama Y, Slavin S, Arnold R, Hiepe F, et al. Randomized controlled trials of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases: The evolution from myeloablative to lymphoablative transplant regimens. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3750. doi: 10.1002/art.22256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mineo D, Ricordi C, Xu X, Pileggi A, Garcia-Morales R, Khan A, et al. Combined islet and hematopoietic stem cell allotrans-plantation: A clinical pilot trial to induce chimerism and graft tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]