Abstract

Background

Glucose repression is a global regulatory system in baker’s yeast. Maltose metabolism in baker’s yeast strains is negatively influenced by glucose, thereby affecting metabolite productivity (leavening ability in lean dough). Even if the general repression system constituted by MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 factors has already been reported, the functions of these three genes in maltose metabolism remain unclear. In this work, we explored the effects of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 deletion on the alleviation of glucose-repression to promote maltose metabolism and leavening ability of baker’s yeast.

Results

Results strongly suggest that the deletion of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 can exert various effects on glucose repression for maltose metabolism. The deletion of TUP1 was negative for glucose derepression to facilitate the maltose metabolism. By contrast, the deletion of MIG1 and/or SSN6, rather than other double-gene or triple-gene mutations could partly relieve glucose repression, thereby promoting maltose metabolism and the leavening ability of baker’s yeast in lean dough.

Conclusions

The mutants of industrial baker’s yeast with enhanced maltose metabolism and leavening ability in lean dough were developed by genetic engineering. These baker’s yeast strains had excellent potential industrial applications.

Keywords: Baker’s yeast, Glucose repression, MIG1, TUP1, SSN6, Maltose metabolism

Background

Baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is the key microorganism used in the baking industry. Although a small amount of free sugars exists in lean dough with no added sugar, maltose represents the principal source of fermentable carbon during dough fermentation [[1]–[3]]. A good baker’s yeast should rapidly ferment maltose. However, glucose and fructose are the first sugars to be used during fermentation, and the presence or uptake of glucose has a negative impact on the metabolism of other carbon sources [[4]–[7]]. Given that the genes involved in maltose utilization are repressed by glucose, a reasonable way to improve maltose metabolism and leavening ability of baker’s yeast is by effectively alleviating glucose repression.

Mig1, a Cys2His2 zinc-finger protein, binds to the promoters of several genes and represses their transcription when glucose is added to the medium [[8]–[10]]. Hu et al. have shown that Mig1p represses the transcription of all three MAL genes essential to maltose metabolism by binding the upstream genes [[11]]. In addition, Mig1 inhibits transcription by recruiting the general co-repressor complex Ssn6-Tup1 [[12]]. Ssn6-Tup1 is one of the first co-repressor complexes to be identified. As with other co-repressors, the specificity of repression is determined by sequence-specific DNA binding repressors, which recruit Ssn6-Tup1 to the target gene promoters; these repressors include Mig1 [[13]–[16]]. Therefore, a strong correlation among MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 for glucose repression was observed. Previous studies have shown that the maltose metabolism of baker’s yeast could be partly glucose derepressed by MIG1 single-gene mutant through enhancing the transcription of the MAL gene [[17]–[19]]. However, the effect of relieving glucose repression on maltose metabolism of baker’s yeast by silencing TUP1 and/or SSN6 remains unclear. Furthermore, maltose metabolism of baker’s yeast through combination mutations of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6, which breaking the regulatory pathway of glucose repression, remains unclear.

In this study, we disrupted the regulatory pathway of glucose repression by deleting MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 to investigate the effects of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 on maltose metabolism and leavening ability of baker’s yeast. The results explicitly suggest that the deletion of the MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 genes lead to different results in the tested conditions. Deletion of MIG1 and/or SSN6 is more efficient than TUP1 deletion and other combination deletions of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 on glucose derepression for maltose metabolism and leavening ability of baker’s yeast in lean dough. This finding lays a foundation for the optimization of industrial baker’s yeast strains.

Results

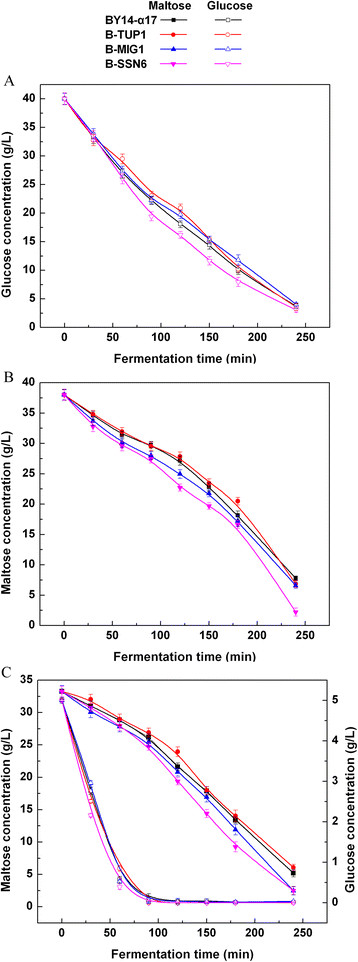

Sugar consumption of single-gene deletion strains in low sugar model liquid dough (LSMLD) medium

The impact of single-gene mutation of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 on sugar consumption was assayed in three LSMLD media. The TUP1 single-gene-deletion strain B-TUP1 cannot rapidly utilize maltose and is inferior to the parental strain BY14-α17, when glucose was exhausted in the glucose-maltose LSMLD medium (Figure 1C). Compared with the parental strain BY14-α17, the MIG1 single-gene-deletion strain B-MIG1 did not evidently change in glucose and maltose LSMLD media (Figures 1A to B). However, compared with the parental strain, a 10.8% increase of maltose utilization efficiency (21.3% in the parental strain and 23.6% in the strain B-MIG1, P < 0.05) of the strain B-MIG1 was observed in glucose-maltose LSMLD medium, when glucose was exhausted (Figure 1C). Simultaneously, the time span between the point when half of the glucose and that of the maltose had been consumed decreased by 10.2% compared with the parental strain (Table 1). The utilization efficiency of sugar distinctly increased in the SSN6 single-gene-deletion strain B-SSN6 compared with the parental strain BY14-α17. The maltose utilization efficiency in B-SSN6 was 18.3% and 19.7% higher than that of the parental strain in maltose (79.6% in the parental strain and 94.2% in the strain B-SSN6, P < 0.05) and glucose-maltose (21.3% in the parental strain and 25.5% in the strain B-SSN6, P < 0.05) LSMLD media, respectively (Figures 1B to C). Furthermore, compared with the parental strain BY14-α17, the time span in B-SSN6 decreased from 2.15 h to 1.76 h (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Concentration of residual sugar in parental strain and single-gene mutants in LSMLD medium. Fresh yeast cells were inoculated into (A) glucose LSMLD medium, (B) maltose LSMLD medium and (C) glucose-maltose LSMLD medium, and were sampled at suitable intervals. Data are average of three independent experiments and error bars represent ± SD.

Table 1.

Time span of the parental strain and the transformants

|

Strains |

BY14-α17 |

B-MIG1 |

B-TUP1 |

B-SSN6 |

B-MIG1-TUP1 |

B-MIG1-SSN6 |

B-TUP1-SSN6 |

B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 |

| Time span (h) a | 2.15 ± 0.10 | 1.93 ± 0.11* | 2.22 ± 0.12* | 1.76 ± 0.13* | 2.07 ± 0.09 | 1.92 ± 0.14* | 2.30 ± 0.10* | 2.32 ± 0.11** |

These results demonstrate that the single-gene deletion of the three genes (MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6) resulted in different effects on the alleviation of glucose repression in the maltose utilization of baker’s yeast. Single-gene deletions of SSN6 and MIG1 promote the glucose derepression. Particularly, the single-gene deletion of SSN6 was more effective than the MIG1 single-gene deletion. However, TUP1 single-gene deletion was negative to relieve glucose repression to promote the maltose metabolism.

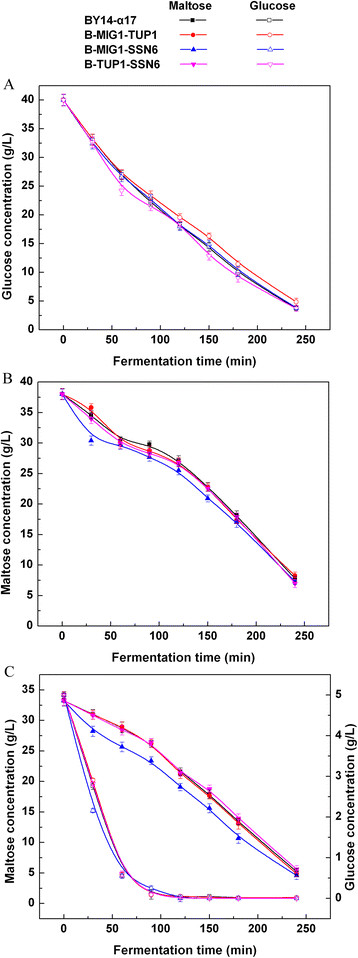

Sugar consumption of double-gene deletion strains in LSMLD medium

The maltose metabolism was tested for the double-gene mutants of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 in the LSMLD medium. Although glucose and maltose decreased with BY14-α17 in the strains B-MIG1-TUP1 and B-TUP1-SSN6 in the three LSMLD media (Figure 2), the time span of B-TUP1-SSN6 was still 6.98% higher than the parental strain (Table 1). By contrast, a positive effect with decreased time span (10.7%) was obtained in B-MIG1-SSN6 (Table 1). When the yeast cells were inoculated in the maltose and the glucose-maltose LSMLD media, the strain B-MIG1-SSN6 exhibited a substantially more rapid sugar-uptake than the other strains. Compared with the parental strain BY14-α17, maltose utilization efficiency (21.3% in the parental strain and 29.7% in the strain B-MIG1-SSN6, P < 0.05) distinctly increased by 39.4% in the strain B-MIG1-SSN6, when glucose was exhausted in the glucose-maltose LSMLD medium (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Concentration of residual sugar in parental strain and double-gene mutants in LSMLD medium. Fresh yeast cells were inoculated into (A) glucose LSMLD medium, (B) maltose LSMLD medium and (C) glucose-maltose LSMLD medium, and sampled at suitable intervals. Data are average of three independent experiments and error bars represent ± SD.

These results indicate that the double-gene deletion of the three genes (MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6) also generated different effects on the maltose metabolism of baker’s yeast by alleviating glucose repression. The co-gene-deletion of MIG1 and SSN6 mitigated glucose repression, which is more efficient than MIG1-TUP1 and TUP1-SSN6 double-gene deletions with no evident function in maltose metabolism.

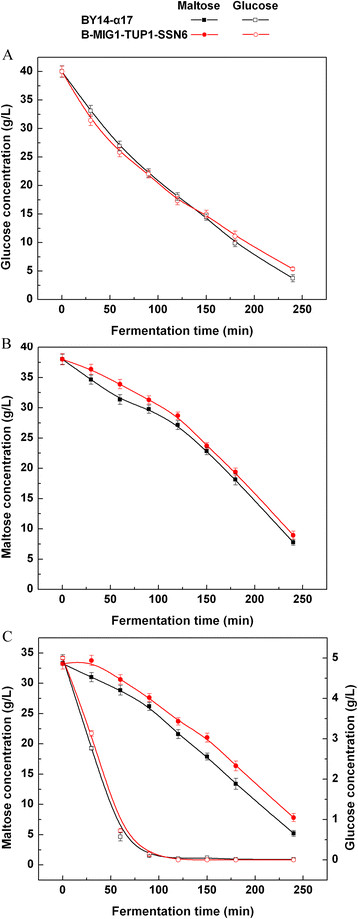

Sugar consumption of the triple-gene deletion strain in LSMLD medium

The maltose metabolism was further investigated with B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6, which performs the triple-gene-deletion of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6. Surprisingly, in B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6, the maltose uptake was considerably delayed compared with the parental strain BY14-α17 until the termination of the process in the maltose LSMLD medium (Figure 3B). Compared with the parental strain, the maltose utilization efficiency (21.3% in the parental strain and 16.9% in the strain B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6, P < 0.05) of the strain B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 decreased by 20.7% in the glucose-maltose LSMLD medium (Figure 3C). The consumption of maltose was slower than BY14-α17 throughout the process. Moreover, the time span was evidently increased (from 2.15 h to 2.32 h) (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Concentration of residual sugar in parental strain and triple-gene mutants in LSMLD medium. Fresh yeast cells were inoculated into (A) glucose LSMLD medium, (B) maltose LSMLD medium and (C) glucose-maltose LSMLD medium, and sampled at suitable intervals. Data are average of three independent experiments and error bars represent ± SD.

These results suggest that the MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 triple-gene deletions were unavailable to relieve glucose repression and enhance maltose metabolism of baker’s yeast, though MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 could function as a complex that affects the glucose-repressible genes [[12]].

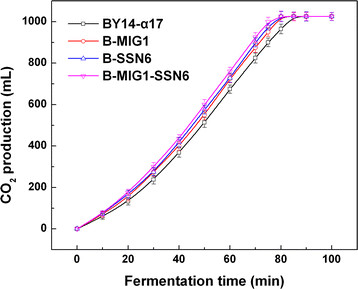

Growth and fermentation properties

Considering the diversity of sugars consumption of the eight strains obtained, we further investigated the growth characteristics (specific growth rate and biomass yield) under different carbon sources and explored the leavening ability in lean dough. The specific growth rate and biomass yield of the single-gene-deletion and double-gene-deletion strains illustrated in Table 2 comparatively remained stable (small difference with no statistical significance), revealing that the single-gene and double-gene deletions of MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 did not influence the growth of the strains. However, the specific growth rate of the triple-gene-deletion B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 (0.14 h−1) was lower than that of the parental strain BY14-α17 (0.19 h−1) in the maltose LSMLD medium. Compared with the parental strain, the biomass yield of B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 decreased from 5.9 g/L to 5.1 g/L in the glucose-maltose LSMLD medium (Table 2). The positive mutants B-MIG1, B-SSN6 and B-MIG1-SSN6 performed well for the leavening ability. Compared with the parental strain BY14-α17, the amount of evolved CO2 by B-MIG1, B-SSN6 and B-MIG1-SSN6 within 70 min increased from 825 mL to 875 mL (P < 0.05), 900 mL (P < 0.01) and 925 mL (P < 0.01), respectively (Figure 4), while the other strains (B-TUP1, B-MIG1-TUP1, B-TUP1-SSN6 and B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6) showed lower CO2 production (data not shown). Moreover, the fermentation time in B-MIG1, B-SSN6 and B-MIG1-SSN6 were evidently shortened, compared with the parental strain.

Table 2.

Growth properties of the parental strain and the transformants

| Strains |

Specific growth rate (h

−1

) |

Biomass yield (g/L) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Maltose | Glucose-maltose | Glucose | Maltose | Glucose-maltose | |

| BY14-α17 |

0.19 ± 0.01 |

0.19 ± 0.00 |

0.16 ± 0.02 |

6.2 ± 0.20 |

6.1 ± 0.21 |

5.9 ± 0.18 |

| B-MIG1 |

0.16 ± 0.03 |

0.18 ± 0.02 |

0.17 ± 0.02 |

5.9 ± 0.23 |

6.0 ± 0.19 |

6.0 ± 0.20 |

| B-TUP1 |

0.17 ± 0.02 |

0.16 ± 0.03 |

0.16 ± 0.01 |

5.9 ± 0.18 |

5.8 ± 0.23 |

5.9 ± 0.23 |

| B-SSN6 |

0.21 ± 0.02 |

0.17 ± 0.01 |

0.18 ± 0.01 |

6.3 ± 0.21 |

6.1 ± 0.23 |

6.1 ± 0.21 |

| B-MIG1-TUP1 |

0.16 ± 0.01 |

0.15 ± 0.04 |

0.18 ± 0.03 |

6.0 ± 0.22 |

5.9 ± 0.21 |

6.0 ± 0.21 |

| B-MIG1-SSN6 |

0.17 ± 0.02 |

0.18 ± 0.01 |

0.18 ± 0.02 |

5.8 ± 0.21 |

6.0 ± 0.20 |

6.1 ± 0.20 |

| B-TUP1-SSN6 |

0.20 ± 0.03 |

0.20 ± 0.02 |

0.15 ± 0.00 |

6.3 ± 0.19 |

6.2 ± 0.22 |

5.8 ± 0.18 |

| B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.05* | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 6.0 ± 0.21 | 5.8 ± 0.20 | 5.1 ± 0.24* |

Values shown represent averages of at least three independent experiments (data are means ± SD). Significant difference of B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 from the parental strain was confirmed by Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05, n = 3).

Figure 4.

CO 2 production by parental strain and positive mutants in lean dough. We mixed 280 g of flour, 150 mL of water, 4 g of salt, and 8 g of fresh yeast into a fermentograph until steady gas formation was achieved. Data are average of three independent experiments and error bars represent ± SD.

These fermentation findings directly correspond with sugar consumption in the LSMLD medium suggesting that the deletion of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 led to different effects on the leavening ability of baker’s yeast in lean dough. Particularly, MIG1 and/or SSN6 deletions could improve the fermentation with stable physiological characteristics.

Discussion

Glucose has dramatic down-regulating effects on the metabolism of other sugars and on the leavening properties of baker’s yeast strains. Glucose does not repress all glucose-repressible genes in a similar manner [[20]]. Numerous reports have shown that the Mig1 repressor and Ssn6-Tup1 co-repressor are central components of the glucose repression machinery involved in the regulation of MAL expression [[12],[21],[22]]. Moreover, MIG1 deletion does not alleviate glucose repression of maltose utilization [[11],[23]]. Probably, the genetic backgrounds of the S. cerevisiae strains used led to the differences in maltose consumptions of the cells. TUP1 and SSN6 mutants produce various phenotypes, including constitutive derepression of numerous glucose-repressible genes, calcium-dependent flocculation, mating-type defects in MATα cells and non-sporulation of homozygous diploids [[24],[25]]. However, the different combinations of mutated MIG1, TUP1 and SSN6 have never been conceived to improve the maltose metabolism. In this study, the deletion mutations of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 were established for the industrial baker’s yeast cells, explicitly demonstrating that the deletion of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 presented different effects on the maltose metabolism and leavening ability of baker’s yeast.

Compared with the parental strain, glucose repression of maltose metabolism was partly alleviated by MIG1 single-gene deletion in B-MIG1 strain (Figures 1B to C), supporting the point that the disruption of MIG1 causes partial alleviation of glucose repression by the secreted metabolites [[11],[22]]. Surprisingly, an apparent difference was observed between the two members of the co-repressor Ssn6-Tup1, SSN6 and TUP1. The trend for sugar consumption suggests that the maltose metabolism in TUP1 single-gene-deletion strain B-TUP1 was longer than the parental strain BY14-α17, pointing to a negative alleviation of glucose repression. In contrast, glucose repression was partially relieved in SSN6 single-gene-deletion strain B-SSN6, increasing maltose metabolism (Figures 1B to C). The different functional domains of Tup1 and Ssn6 involved in glucose control are probably the major causes of the different effects of the two gene deletions on glucose repression. The functional domains of Ssn6 primarily consist of 10 tandem copies of a TPR motif and are specifically necessary for the repression of glucose-regulated genes [[26]]. Different domains of Tup1 can cause the repression of different target genes. For example, some WD motifs or N-terminus domains of Tup1 are not essential for repression of genes regulated by glucose [[26]–[29]]. However, certain regions of Tup1 could be necessary for the high-level expression of glucose-repressed genes, such as GAL genes for galactose fermentation [[30]]. Thus, we propose that the regions of Tup1 crucial to the expression of MAL genes are disrupted through complete gene deletion. Therefore, MIG1 single-gene deletion and SSN6 single-gene deletion were considered effective in improving maltose metabolism in the industrial baker’s yeast.

The combined effects of MIG1, SSN6 and TUP1 on the maltose metabolism in industrial baker’s yeast were further investigated. Combined mutations of TUP1 with MIG1 or SSN6 compensated for the slow maltose metabolism of the strain B-TUP1, while the rates of maltose consumption in the mutants B-MIG1-TUP1 and B-TUP1-SSN6 were only close to that of the parental strain BY14-α17 (Figure 2). TUP1 single-gene deletion is possible in its negative effect limited to the alleviation of glucose repression. Hence, MIG1 or SSN6 deletion with TUP1 cannot enhance the maltose metabolism. The double-gene mutant strain B-MIG1-SSN6 was less glucose repressed compared with the parental strain (Figure 2C). This finding corresponds with the studies, which showed that the interactions with DNA-binding repressors are mainly mediated through the different surfaces of Ssn6, and that Ssn6 specifically interacts with Mig1 [[31],[32]]. The insufficient alleviation of glucose repression in B-MIG1-SSN6 could result from the co-action of Mig1 and Ssn6. Although Mig1 is unessential for tethering Ssn6 to the MAL upstream, it is important for Ssn6-mediated repression in response to glucose. Surprisingly, the triple-gene mutant B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 was more glucose repressed than the parental strain (Figure 3). Considering that the interactions of Ssn6-Tup1 complex contain diverse mechanisms, other mechanisms affecting the MAL genes expression are also possibly involved in the regulation of the repression by the Mig1-Tup1-Ssn6 complex [[13],[33]]. In addition, the inferior sugar uptake in B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 could be caused by the feeble physiological characteristic compared with the parental strain (Table 2).

Single-gene and double-gene deletions did not present any evident changes in the specific growth rate and biomass yield in the three LSMLD media (Table 2). In other words, the growth properties of single-gene and double-gene deletions of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6 with no distinctive difference (no statistical significance) were insufficient to affect the maltose metabolism. Therefore, the differences in maltose metabolism (maltose utilization and CO2 production) do not have strong correlations with the indistinct differences in the physiological effects of the baker’s yeast in this study.

The effective alleviation of glucose repression or the rapid transition from glucose to maltose metabolism is essential to improve the leavening ability of baker’s yeast in lean dough. The single-gene MIG1/SSN6 and co-gene-deletions of MIG1 and SSN6 decreased the span time in the glucose-maltose LSMLD medium with stable growth properties (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, these deletions could cause efficient leavening ability (Figure 4). Furthermore, evident increase of the leavening ability level was observed in B-MIG1-SSN6, indicating that Mig1 and Ssn6 collectively act for the inhibition of maltose-utilizing genes. Thus, co-gene deletion of MIG1 and SSN6 could significantly enhance leavening ability of baker’s yeast. These advantages are consistent with the requirement for the leavening ability of an industrial baker’s yeast strain. With minimal transformation, SSN6 or MIG1 single-gene deletion is necessary to obtain a baker’s yeast strain with rapid maltose metabolism.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that the glucose repression involved in the maltose metabolism can be modulated at different levels through the different mutations of MIG1 and/or TUP1 and/or SSN6. The deletion of TUP1 was negative to alleviate glucose repression to facilitate the maltose metabolism. In contrast, deletions of MIG1 and/or SSN6 were efficient to relieve glucose repression, therefore, promoting maltose metabolism and the leavening ability of baker’s yeast in lean dough. Hence, such baker’s yeast has excellent commercial and industrial applications.

Materials and methods

Strains and vectors

Table 3 summarizes the genetic properties of all strains and plasmids used in this study.

Table 3.

Characteristics of strains and plasmids used in the present study

| Strains or plasmids | Relevant characteristic | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

|

Strains |

|

|

|

E. coli

DH5α |

Φ80 lacZΔM15 ΔlacU169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 |

Stratagene |

|

BY14-α17 |

MAT α, Industrial baker’s yeast |

This study |

|

B-MIG1 |

MAT α, ΔMIG1:: loxP |

This study |

|

B-TUP1 |

MAT α, ΔTUP1:: loxP |

This study |

|

B-SSN6 |

MAT α, ΔSSN6:: loxP |

This study |

|

B-MIG1-TUP1 |

MAT α, ΔMIG1:: loxP, ΔTUP1:: loxP |

This study |

|

B-MIG1-SSN6 |

MAT α, ΔMIG1:: loxP, ΔSSN6:: loxP |

This study |

|

B-TUP1-SSN6 |

MAT α, ΔTUP1:: loxP, ΔSSN6:: loxP |

This study |

|

B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 |

MAT α, ΔMIG1:: loxP, ΔTUP1:: loxP, ΔSSN6:: loxP |

This study |

|

Plasmids |

|

|

|

pUG6 |

E. coli/S. cerevisiae shuttle vector, containing Amp

+

and loxP-kanMX-loxP disruption cassette |

[[34]] |

|

pUC19 |

Apr, cloning vector |

Invitrogen |

|

pSH-Zeocin |

Zeor, Cre expression vector |

[[35]] |

|

pKAB |

Apr, Kanr, Am-KanMX-Bm |

[[10]] |

|

pUC-KA

t

B

t

|

Apr, Kanr, At-KanMX-Bt |

This study |

| pUC-KA s B s | Apr, Kanr, As-KanMX-Bs | This study |

Growth, cultivation and fermentation conditions

Recombinant DNA was amplified in Escherichia coli DH5α, which was grown at 37°C in Luria–Bertani medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. The plasmid was obtained using a Plasmid Mini Kit II (D6945, Omega, USA).

The yeast strains were maintained in yeast extract peptone dextrose (YEPD) medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, and 20 g/L glucose) at 30°C. Over the next enrichment of the molasses medium, cells were harvested through centrifugation (4°C, 1500 ×g, 5 min) and were washed twice with sterile water at 4°C in the succeeding fermentation experiments. To investigate the degree of repression between the three repression factors under different concentrations of extracellular maltose, we used the low sugar model liquid dough fermentation medium [LSMLD fermentation medium, 2.5 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 5 g/L urea, 16 g/L KH2PO6, 5 g/L Na2HPO4, 0.6 g/L MgSO4, 0.0225 g/L nicotinic acid, 0.005 g/L Ca-pantothenate, 0.0025 g/L thiamine, 0.00125 g/L pyridoxine, 0.001 g/L riboflavin, and 0.0005 g/L folic acid], containing one of the three specified carbon sources (40 g/L glucose, 38 g/L maltose, and 33.25 g/L maltose mixed with 5 g/L glucose).

To select Zeocin-resistant yeast strains, 500 mg/L Zeocin (Promega, Madison, United States) was added to the YEPD plates for the yeast culture. Then, the YEPG medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, and 20 g/L galactose) was used for Cre expression in the yeast transformants.

Construction of plasmid and yeast transformants

Genomic yeast DNA was prepared from the industrial baker’s yeast strain BY14-α17 using a yeast DNA kit (D3370-01, Omega, USA). The PCR primers used in this work are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Primers used in the present study (restriction sites are italics)

| Primers | Sequence (5’ → 3’) |

|---|---|

|

For plasmid construction |

|

| TA-U |

CCGGAATTCAAATGAAATAATACGGGAAGAGCG |

| TA-D |

CGGGGTACCCGGTAGCGATAATGTAAGAGGGTT |

| TB-U |

ACGCGTCGACGAACAGAACACAAAAGGAACAC |

| TB-D |

ACATGCATGCGAACCGCAATATTCAGAAACAC |

| SA-U |

CCGGAATTCCTTATAACGTGGGCCATGTCAT |

| SA-D |

CGCGGATCCCTAGTGACGTTGTCGTATTTGG |

| SB-U |

CGCGGATCCTCAACGAGAAATGTTGTGTAGC |

| SB-D |

CCCAAGCTTACATATGCTCATCGGGAAAACC |

| Kan-U |

CGCGGATCCCAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC |

| Kan-D |

CGCGGATCCGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATCTG |

|

For PCR verification |

|

| YT-U |

TCTTGTCTGTCTGCTTCTTCACTGT |

| YT-D |

AAAGAGTGTGAAGTGACGGCTATG |

| YS-U |

CACACTCCGTTCTTAGTGGTTGTT |

| YS-D |

ATCCACCGTAGAACCCAAAGCATT |

| K-U |

CTTGCTAGGATACAGTTCTCACATCA |

| K-D |

CGCATCAACCAAACCGTTATTCATTC |

| Z-U |

CCCACACACCATAGCTTCA |

| Z-D | AGCTTGCAAATTAAAGCCTT |

An upstream homologous fragment of the TUP1 gene was amplified by PCR using BY14-α17 genomic DNA as template with TA-U and TA-D primers. A downstream homologous fragment was similarly amplified using TB-U and TB-D primers. Then, the PCR products were digested using the appropriate endonucleases and were cloned to the pUC19 cloning vector at EcoR I and Kpn I sites, and Sal I and Sph I sites, respectively, to construct plasmid pUC-AtBt. The KanMX cassette, which was amplified by PCR using pUG6 as the template with the primers Kan-U and Kan-D, was cloned to construct pUC-AtBt after being digested with the appropriate endonucleases to produce the final plasmid, which was designated as pUC-KAtBt. Based on the aforementioned strategy, the pUC-KAsBs plasmid was constructed by inserting the upstream homologous fragment SSN6A, KanMX cassette, and downstream homologous fragment SSN6B into the pUC19 cloning vector.

Baker’s yeast transformation was achieved through lithium acetate/PEG method [[36]]. The deletion cassette of TUP1A-loxP-KanMX-loxP-TUP1B was amplified and transformed into the industrial baker’s yeast BY14-α17. The fragment was integrated into the chromosome at the TUP1 locus of BY14-α17 by homologous recombination to construct the TUP1 deletion strain. The selection of TUP1 deletion strain was performed using the YEPD medium supplemented with 800 mg/L G418. After selection, recombinant strains were verified with the primers listed in Table 4. Cre recombinase was expressed and KanMX was excised after introducing the plasmid pSH-Zeocin into the TUP1 deletion strain, thus resulting in B-TUP1. The same procedure was utilized to construct B-MIG1 and B-SSN6. Based on the aforementioned strategy, the double-gene mutation strains B-MIG1-TUP1, B-MIG1-SSN6 and B-TUP1-SSN6 were constructed by transforming the second deletion cassette into the single-gene mutation strains. The triple-gene mutation strain B-MIG1-TUP1-SSN6 was constructed by transforming SSN6A-loxP-KanMX-loxP-SSN6B into B-MIG1-TUP1. Finally, all of the transformants were verified through PCR with the primers listed in Table 4.

Determination of specific growth rate and biomass yield

After incubating for 24 h, the mixtures of cell culture and medium were mixed in a specific pore plate in appropriate proportions, and the growth curve was detected using bioscreen automated growth curves (Type Bioscreen C, Finland). The specific growth rate was determined with the ratio of the growth velocity to cell concentration.

Nitrocellulose filters with a pore size of 0.45 mm (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) were pre-dried in a microwave oven at 150 W for 10 min and were subsequently weighed. Harvested cells were obtained from 10 mL of cell culture, washed twice with isometric distilled water, and dried at 105°C for 24 h. The biomass yield was determined from the slopes of the plots of biomass dry weight versus the amount of consumed sugar during exponential growth. Experiments were conducted at least thrice.

Determination of leavening ability

The leavening ability of yeast cells was assayed by measuring the CO2 production in lean dough. Lean dough consisted of 280 g of flour, 150 mL of water, 4 g of salt, and 8 g of fresh yeast. The dough was evenly and quickly mixed for 5 min at 30 ± 0.2°C, and placed inside the box of a fermentograph (Type JM451, Sweden). CO2 production was recorded at 30°C. Experiments were conducted at least thrice.

Analysis of sugar consumption

For extracellular sugar measurements, cultures were sampled at 30°C at suitable intervals for 4 h. The maltose content was measured through 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid method (DNS). HPLC with a refractive index detector and an Aminex® HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was utilized at 65°C with 5 mM H2SO4 as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min [[37]] to analyze the mixed sugars filtered through 0.45 μm pore size cellulose acetate filters (Mil-lipore Corp, Danvers, MA, USA). The maltose utilization efficiency in maltose LSMLD medium was determined by the ratio of the consumed maltose in 240 min and the total maltose. The maltose utilization efficiency in glucose-maltose LSMLD medium was determined by the ratio of the consumed maltose, when glucose was exhausted, and the total maltose. Based on the consumption curves of glucose and maltose in the glucose-maltose LSMLD medium, the time span between the point when half of the glucose and that of the maltose had been consumed was determined. Experiments were conducted at least thrice.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, and were accompanied by the number of experiments independently performed. The differences of the transformants compared with the parental strain were confirmed by Student’s t-test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant differences in statistics.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XL carried out the experiments and drafted the manuscript. XWB and HYS participated in the plasmid and strain construction. CYZ and DGX conceived the study and reviewed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xue Lin, Email: linxiaoxuelx@163.com.

Cui-Ying Zhang, Email: cyzhangcy@tust.edu.cn.

Xiao-Wen Bai, Email: 735754495@qq.com.

Hai-Yan Song, Email: 907678195@qq.com.

Dong-Guang Xiao, Email: xdg@tust.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

The current study was financially supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2013AA102106), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171730; 31000043), and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT1166).

References

- Cousseau FE, Alves SL Jr, Trichez D, Stambuk BU. Characterization of maltotriose transporters from the Saccharomyces eubayanus subgenome of the hybrid Saccharomyces pastorianus lager brewing yeast strain Weihenstephan 34/70. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2013;56:21–29. doi: 10.1111/lam.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincón AM, Codón AC, Castrejón F, Benítez T. Improved properties of baker’s yeast mutants resistant to 2-deoxy-d-glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:4279–4285. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.9.4279-4285.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang TX, Xiao DG, Gao Q. Characterisation of maltose metabolism in lean dough by lagging and non-lagging baker’s yeast strains. Ann Microbiol. 2008;58:655–660. doi: 10.1007/BF03175571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horák J. Regulations of sugar transporters: insights from yeast. Curr Genet. 2013;59:1–31. doi: 10.1007/s00294-013-0388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz P, Alms GR, Haystead TA, Carlson M. Regulatory interactions between the Reg1-Glc7 protein phosphatase and the Snf1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1321–1328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.4.1321-1328.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Olsson L, Nielsen J. Glucose control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the role of Mig1 in metabolic functions. Microbiology. 1998;144:13–24. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstrepen KJ, Iserentant D, Malcorps P, Derdelinckx G, Van Dijck P, Winderickx J, Pretorius IS, Thevelein JM, Delvaux FR. Glucose and sucrose: hazardous fast-food for industrial yeast? Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Yue M, Li S, Bai X, Zhao X, Du Y. The impact of MIG1 and/or MIG2 disruption on aerobic metabolism of succinate dehydrogenase negative Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:733–738. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2894-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vit MJ, Waddle JA, Johnston M. Regulated nuclear translocation of the Mig1 glucose repressor. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1603–1618. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhang C, Dong J, Wu M, Zhang Y, Xiao D. Enhanced leavening properties of baker’s yeast overexpressing MAL62 with deletion of MIG1 in lean dough. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;39:1533–1539. doi: 10.1007/s10295-012-1144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Olsson L, Rønnow B, Mikkelsen JD, Nielsen J. Alleviation of glucose repression of maltose metabolism by MIG1 disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4441–4449. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4441-4449.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treitel MA, Carlson M. Repression by SSN6-TUP1 is directed by MIG1, a repressor/activator protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3132–3136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie JK, Trumbly RJ, Dent SY. Histone-dependent association of Tup1-Ssn6 with repressed genes in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:693–703. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.3.693-703.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keleher CA, Redd MJ, Schultz J, Carlson M, Johnson AD. Ssn6-Tup1 is a general repressor of transcription in yeast. Cell. 1992;68:709–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon SE, Rizzo JM, Tatomer DC, Lieb JD, Buck MJ: The stress response factors Yap6, Cin5, Phd1, and Skn7 direct targeting of the conserved co-repressor Tup1-Ssn6 in S. cerevisiae .PLoS One 2011, 6:e19060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- García–Sánchez S, Mavor AL, Russell CL, Argimon S, Dennison P, Enjalbert B, Brown AJ. Global roles of Ssn6 in Tup1- and Nrg1-dependent gene regulation in the fungal pathogen, Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2913–2925. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Nehlin JO, Ronne H, Michels CA. MIG1-dependent and MIG1-independent glucose regulation of MAL gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1995;28:258–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00309785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJL, Olsson L, Ronnow B, Mikkelsen JD, Nielsen J. Glucose and Maltose Metabolism in MIG1-disrupted and MAL-constitutive Strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Technol Biotechnol. 1997;35:287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller HJ. Transcriptional control of nonfermentative metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 2003;43:139–160. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F, Winderickx J, Thevelein JM. Glucose-sensing and -signalling mechanisms in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002;2:183–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2002.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geladé R, Van de Velde S, Van Dijck P, Thevelein JM: Multi-level response of the yeast genome to glucose.Genome Biol 2003, 4:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Olsson L, Nielsen J. The role of metabolic engineering in the improvement of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: utilization of industrial media. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000;26:785–792. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Rasmussen JJ, Rønnow B, Olsson L, Nielsen J. Investigation of the impact of MIG1 and MIG2 on the physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biotechnol. 1999;68:197–212. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(98)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams FE, Varanasi U, Trumbly RJ. The CYC8 and TUP1 proteins involved in glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are associated in a protein complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varanasi US, Klis M, Mikesell PB, Trumbly RJ. The Cyc8 (Ssn6)-Tup1 corepressor complex is composed of one Cyc8 and four Tup1 subunits. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6707–6714. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico PM, Zitomer RS. Mutational analysis of the Tup1 general repressor of yeast. Genetics. 1998;148:637–644. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzamarias D, Struhl K. Distinct TPR motifs of Cyc8 are involved in recruiting the Cyc8-Tup1 corepressor complex to differentially regulated promoters. Genes Dev. 1995;9:821–831. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Varanasi U, Trumbly RJ. Functional dissection of the global repressor Tup1 in yeast: dominant role of the C-terminal repression domain. Genetics. 2002;161:957–969. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas–Maceiras M, Freire–Picos MA, Torres AM. Transcriptional repression by Kluyveromyces lactis Tup1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;38:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Hong ME, Jung SC, Ha SJ, Yu BJ, Koo HM, Park SM, Seo JH, Kweon DH, Park JC, Jin YS. Improved galactose fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae through inverse metabolic engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:621–631. doi: 10.1002/bit.22988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KH, Struhl K. The Cyc8-Tup1 complex inhibits transcription primarily by masking the activation domain of the recruiting protein. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2525–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.179275.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichos–Chronakis M, Gligoris T, Tzamarias D. The Snf1 kinase controls glucose repression in yeast by modulating interactions between the Mig1 repressor and the Cyc8-Tup1 co-repressor. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:368–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallier LG, Carlson M. Synergistic release from glucose repression by mig1 and ssn mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1994;137:49–54. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueldener U, Heinisch J, Koehler GJ, Voss D, Hegemann JH: A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre -mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast.Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30:e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lu J, Dong J, Wu D, Chen Y, Guo X, Shi Y, Sun X, Xiao D. Construction of recombinant industrial brewer’s yeast with lower diacetyl production and proteinase A activity. Eur Food Res Technol. 2012;235:951–961. doi: 10.1007/s00217-012-1821-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf J, Zimmermann FK, Müller S. Simultaneous genomic overexpression of seven glycolytic enzymes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2000;26:688–698. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]