Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is a principal regulator of calcium balance in physiological and pathological conditions associated with cardiovascular disorders and plays a major physiological role in bone homeostasis (Figure 1). PTH systemically controls bone remodeling by modulating the bone marrow microenvironment and regulating osteogenic signaling pathways.1 PTH and its related peptide (PTHrP) can have both anabolic and catabolic effects. While intermittent administration of PTH is osteoanabolic and anti-osteoporotic via stimulation of bone formation, its continuous administration may cause catabolic osteoporotic changes. Experimental studies showed that intermittent injection of full length PTH (PTH1–84) or its N-terminal fragment, (PTH1-34) increases bone formation with normal microarchitecture by coupling bone remodeling1 as well as promoting bone vascular structure and function.2 Clinically, intermittent administration of PTH is an established osteoanabolic therapy that improves quality of life in patients with severe osteoporosis.3 However, potential adverse effects by long-term use of PTH have not been fully elucidated.

Figure 1. PTH as a novel mediator of bone-vascular-renal interaction.

Cardiovascular disorders include but not limited to valvular and vascular calcification, atherosclerosis (inflammation) and hypertension.

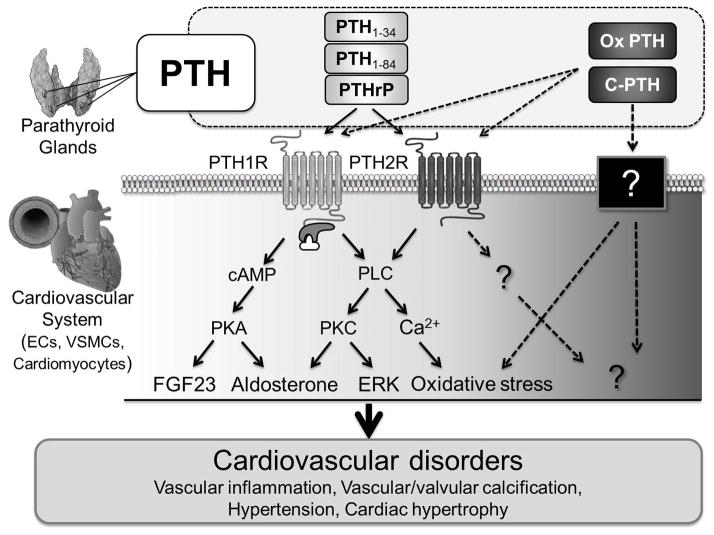

The presence of PTH receptors within the cardiovascular system,4 including vasculature (smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells) and heart (cardiomyocytes), suggests that secreted PTH may play a role in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases beyond its role in mineral and bone metabolism (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hypothetical signaling pathways of PTH receptor in cardiovascular disorders based on previously published reports.

Solid arrows: previously reported pathways; dotted arrows: postulated but unknown pathways; ECs: endothelial cells; VSMCs: vascular smooth muscle cells; PTHrP: PTH-related peptide; Ox PTH: oxidized PTH; C-PTH: C-terminal PTH; PTH1 2R: PTH 1,2 receptor; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PLC: phospholipase C; PKA: protein kinase A; PKC: protein kinase C.

Clinically, patients with primary hyperparathyroidism have a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and suffer from a broad spectrum of adverse cardiovascular disorders such as coronary microvascular dysfunction, subclinical aortic valve calcification, increased aortic stiffness, endothelial dysfunction and hypertension.5 Furthermore, secondary hyperparathyroidism, the most significant complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), causes abnormal bone disorders as well as extra-skeletal calcification, such as vascular and valvular calcification, and increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.6 Moreover, recent observational studies indicate that high PTH is an important novel cardiovascular risk factor with powerful predictive value for cardiovascular disease and mortality in individuals even without hyperparathyroidism.7

In this issue of Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, Hagström et al. highlighted PTH as a strong risk predictor for clinical and subclinical atherosclerotic disease using two Swedish community-based populations with over 1000 70-year-old individuals. The first cohort (PIVUS study) revealed that intact PTH is independently associated with the burden of atherosclerosis, even after adjustment to vascular risk factors and mineral metabolism variables. In a second independent cohort (USLAM study) with a follow up of 16.7 years, PTH was associated with increased long-term risk of non-fatal atherosclerotic disease in peripheral and large vessels and accounted for 11.6% of the population-attributable risk proportion. These findings are consistent with previously published studies. In a prospective study of healthy individuals (n=476), serum PTH levels were positively associated with the number of stenotic coronary arteries.8 Further PTH is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients with stage 3/4 CKD independent of calcium-phosphate levels.9 The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) also demonstrated the association among PTH and hypertension, and a tripartite association among PTH, carotid stiffness and systolic blood pressure, thus providing new evidence for the role of PTH in cardiovascular diseases.10,11

Recent studies have indicated a protective effect of PTH lowering by cinecalcet on cardiovascular disorders, including the reduction of abdominal aortic calcification12 and arterial stiffness13, while reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients on hemodialysis with complications due to hyperparathyroidism was not detected. The association between long-term exposure of high PTH and vascular14 and valvular calcification15 has been demonstrated mainly in patients with renal dysfunction.

Given its elevated expression in CKD patients, these findings suggest that cardiovascular calcification might be the key link between PTH and atherosclerosis. Nevertheless, there have been several experimental studies challenging this hypothesis. PTH1-34 has been shown to reduce vascular calcification in vitro and in vivo16 by suppressing vascular BMP2-Msx2-Wnt signaling.17 Like PTH1-34, PTHrP suppresses the expression of osteogenic markers and calcium deposition in smooth muscle cells.18 Conversely, the PTH1R antagonist PTHrP7–34 enhances alkaline phosphatase expression and calcium deposition in vitro.18

It is important to mention that most of these experimental studies were performed using the N-terminal fragment of PTH, whereas clinical studies measure intact PTH; indicating that mechanistic studies may not reflect the clinical situation. Moreover, emerging evidence indicate that modifications of PTH alter its biological function. The carboxyl-terminal PTH fragment (C-PTH), which represents 70–95% of circulating PTH, exerts specific effects on calcium homeostasis and bone metabolism, opposite to those of the synthetic agonist of PTH/PTHrP receptor,19 suggesting that C-PTH may promote vascular calcification. Also, in patients requiring dialysis a certain proportion of circulating PTH is oxidized and thus loses its PTH receptor-stimulating properties, but remains detectable by immunoassay.20 Therefore, current PTH assay systems may inadequately reflect PTH-related cardiovascular abnormalities in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Indeed, in a diabetic rat model with metabolic disorder and elevated oxidative stress the positive bone-anabolic effects of PTH were blunted,21 suggesting that conditions with high oxidative stress modify PTH. Indeed, a recent clinical study revealed that the mortality in hemodialysis patients was associated with oxidized PTH but not with non-oxidized PTH levels.22 It is intriguing to speculate that oxidative stress – a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, might be an important missing link for the association between PTH and atherosclerotic disease. Oxidized PTH is likely to be increased with age, which in turn associates with accelerated oxidative stress. For the evaluation of PTH as a cardiovascular risk factor it is necessary to assess the biological function and importance of PTH subtypes (e.g. oxidized PTH, C-PTH) that may differ from the most studied PTH forms (PTH1-34, PTH1-84) and thereby introduce different clinical implications, including cardiovascular calcification.

Changes in mineral metabolism as well as interactive cross-talk between the skeletal system and cardiovascular system play a crucial role in vascular disorders such as atherosclerosis or vascular calcification. Although the relationship between osteoporosis and vascular calcification has long been known as the calcification paradox, the key players in this process still remain unclear. Many studies have highlighted an important role for the RANK/RANKL/OPG axis in skeletal and extra-skeletal calcification.23 PTH could be a potential candidate to add to the list of mediators of the bone-vascular interaction.

The ultimate clinical goal in the field is to establish a therapy for preventing bone loss without increasing the risk for cardiovascular disorders. In the present study, Hagström et al. showed that the highest quartile of PTH (> 5.27 pmol/L) in the cohort was associated with the degree of atherosclerosis and increased risk of non-fatal atherosclerotic disorders. Considering the causal role of PTH in atherosclerosis as suggested above, a possible cardiovascular intervention for patients might be the lowering of specific subtypes of PTH that do not affect bone metabolism. In addition, visualizing of extra-skeletal calcification24 and correlation of calcium scores with PTH levels in the future clinical trials would help answering many key questions. Taken together, PTH may provide not only critical information about bone disease, but also offer novel preventive measures and therapeutic insights into patients’ cardiovascular health.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Dr. Aikawa is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL114805; R01HL109506).

Footnotes

Disclosures

No disclosures.

References

- 1.Crane JL, Cao X. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and tgf-beta signaling in bone remodeling. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:466–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI70050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roche B, Vanden-Bossche A, Malaval L, Vico L, Normand M, Jannot M, Chaux R, Lafage-Proust MH. Parathyroid hormone 1–84 targets bone vascular structure and perfusion in mice: Impacts of its administration regimen and of ovariectomy. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2191. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron R, Hesse E. Update on bone anabolics in osteoporosis treatment: Rationale, current status, and perspectives. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012;97:311–325. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemens TL, Cormier S, Eichinger A, Endlich K, Fiaschi-Taesch N, Fischer E, Friedman PA, Karaplis AC, Massfelder T, Rossert J, Schluter KD, Silve C, Stewart AF, Takane K, Helwig JJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein and its receptors: Nuclear functions and roles in the renal and cardiovascular systems, the placental trophoblasts and the pancreatic islets. British journal of pharmacology. 2001;134:1113–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macfarlane DP, Yu N, Leese GP. Subclinical and asymptomatic parathyroid disease: Implications of emerging data. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2013;1:329–340. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver J, Naveh-Many T. Fgf-23 and secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease. Nature reviews Nephrology. 2013;9:641–649. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagstrom E, Hellman P, Larsson TE, Ingelsson E, Berglund L, Sundstrom J, Melhus H, Held C, Lind L, Michaelsson K, Arnlov J. Plasma parathyroid hormone and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in the community. Circulation. 2009;119:2765–2771. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shekarkhar S, Foroughi M, Moatamedi M, Gachkar L. The association of serum parathyroid hormone and severity of coronary artery diseases. Coronary artery disease. 2014;25:339–342. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lishmanov A, Dorairajan S, Pak Y, Chaudhary K, Chockalingam A. Elevated serum parathyroid hormone is a cardiovascular risk factor in moderate chronic kidney disease. International urology and nephrology. 2012;44:541–547. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9897-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blondon M, Sachs M, Hoofnagle AN, Ix JH, Michos ED, Korcarz C, Gepner AD, Siscovick DS, Kaufman JD, Stein JH, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH. 25-hydroxyvitamin d and parathyroid hormone are not associated with carotid intima-media thickness or plaque in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:2639–2645. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gepner AD, Colangelo LA, Blondon M, Korcarz CE, de Boer IH, Kestenbaum B, Siscovick DS, Kaufman JD, Liu K, Stein JH. 25-hydroxyvitamin d and parathyroid hormone levels do not predict changes in carotid arterial stiffness: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2014;34:1102–1109. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama K, Nakao K, Takatori Y, Inoue J, Kojo S, Akagi S, Fukushima M, Wada J, Makino H. Long-term effect of cinacalcet hydrochloride on abdominal aortic calcification in patients on hemodialysis with secondary hyperparathyroidism. International journal of nephrology and renovascular disease. 2013;7:25–33. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S54731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonet J, Bayes B, Fernandez-Crespo P, Casals M, Lopez-Ayerbe J, Romero R. Cinacalcet may reduce arterial stiffness in patients with chronic renal disease and secondary hyperparathyroidism - results of a small-scale, prospective, observational study. Clinical nephrology. 2011;75:181–187. doi: 10.5414/cnp75181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raggi P, Chertow GM, Torres PU, Csiky B, Naso A, Nossuli K, Moustafa M, Goodman WG, Lopez N, Downey G, Dehmel B, Floege J. The advance study: A randomized study to evaluate the effects of cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin d on vascular calcification in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011;26:1327–1339. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linefsky JP, O’Brien KD, Katz R, de Boer IH, Barasch E, Jenny NS, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B. Association of serum phosphate levels with aortic valve sclerosis and annular calcification: The cardiovascular health study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao JS, Cheng SL, Charlton-Kachigian N, Loewy AP, Towler DA. Teriparatide (human parathyroid hormone (1-34)) inhibits osteogenic vascular calcification in diabetic low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:50195–50202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao JS, Cheng SL, Pingsterhaus JM, Charlton-Kachigian N, Loewy AP, Towler DA. Msx2 promotes cardiovascular calcification by activating paracrine wnt signals. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:1210–1220. doi: 10.1172/JCI24140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng SL, Shao JS, Halstead LR, Distelhorst K, Sierra O, Towler DA. Activation of vascular smooth muscle parathyroid hormone receptor inhibits wnt/beta-catenin signaling and aortic fibrosis in diabetic arteriosclerosis. Circulation research. 2010;107:271–282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scillitani A, Guarnieri V, Battista C, Chiodini I, Salcuni AS, Minisola S, Francucci CM, Carnevale V. Carboxyl-terminal parathyroid hormone fragments: Biologic effects. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2011;34:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hocher B, Armbruster FP, Stoeva S, Reichetzeder C, Gron HJ, Lieker I, Khadzhynov D, Slowinski T, Roth HJ. Measuring parathyroid hormone (pth) in patients with oxidative stress--do we need a fourth generation parathyroid hormone assay? PloS one. 2012;7:e40242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamann C, Picke AK, Campbell GM, Balyura M, Rauner M, Bernhardt R, Huber G, Morlock MM, Gunther KP, Bornstein SR, Gluer CC, Ludwig B, Hofbauer LC. Effects of parathyroid hormone on bone mass, bone strength, and bone regeneration in male rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1197–1206. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tepel M, Armbruster FP, Gron HJ, Scholze A, Reichetzeder C, Roth HJ, Hocher B. Nonoxidized, biologically active parathyroid hormone determines mortality in hemodialysis patients. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98:4744–4751. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofbauer LC, Brueck CC, Shanahan CM, Schoppet M, Dobnig H. Vascular calcification and osteoporosis--from clinical observation towards molecular understanding. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2007;18:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0282-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hjortnaes J, New SE, Aikawa E. Visualizing novel concepts of cardiovascular calcification. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2013;23:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]