Abstract

Background

Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries are experiencing rapid transitions with increased life expectancy. As a result the burden of age-related conditions such as neurodegenerative diseases might be increasing. We conducted a systematic review of published studies on common neurodegenerative diseases, and HIV-related neurocognitive impairment in SSA, in order to identify research gaps and inform prevention and control solutions.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, ‘Banque de Données de Santé Publique’ and the database of the ‘Institut d’Epidemiologie Neurologique et de Neurologie Tropicale’ from inception to February 2013 for published original studies from SSA on neurodegenerative diseases and HIV-related neurocognitive impairment. Screening and data extraction were conducted by two investigators. Bibliographies and citations of eligible studies were investigated.

Results

In all 144 publications reporting on dementia (n = 49 publications, mainly Alzheimer disease), Parkinsonism (PD, n = 20), HIV-related neurocognitive impairment (n = 47), Huntington disease (HD, n = 19), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, n = 15), cerebellar degeneration (n = 4) and Lewy body dementia (n = 1). Of these studies, largely based on prevalent cases from retrospective data on urban populations, half originated from Nigeria and South Africa. The prevalence of dementia (Alzheimer disease) varied between <1% and 10.1% (0.7% and 5.6%) in population-based studies and from <1% to 47.8% in hospital-based studies. Incidence of dementia (Alzheimer disease) ranged from 8.7 to 21.8/1000/year (9.5 to 11.1), and major risk factors were advanced age and female sex. HIV-related neurocognitive impairment’s prevalence (all from hospital-based studies) ranged from <1% to 80%. Population-based prevalence of PD and ALS varied from 10 to 235/100,000, and from 5 to 15/100,000 respectively while that for Huntington disease was 3.5/100,000. Equivalent figures for hospital based studies were the following: PD (0.41 to 7.2%), ALS (0.2 to 8.0/1000), and HD (0.2/100,000 to 46.0/100,000).

Conclusions

The body of literature on neurodegenerative disorders in SSA is large with regard to dementia and HIV-related neurocognitive disorders but limited for other neurodegenerative disorders. Shortcomings include few population-based studies, heterogeneous diagnostic criteria and uneven representation of countries on the continent. There are important knowledge gaps that need urgent action, in order to prepare the sub-continent for the anticipated local surge in neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Neurodegenerative diseases, Parkinsonism, Dementia, HIV-related cognitive impairment, Sub-Saharan Africa

Background

Worldwide, populations are increasingly living longer including in developing countries, where the largest number of elderly people is currently found. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) (Figure 1), life expectancy at birth has increased by about 20 years between 1950 and 2010 [1]. During this same period, while the proportion of people aged 60 years and above has remained constant at around 5%, the absolute number in this group has increased by about four folds from 9.4 million in 1950 (total population 179.5 million) to 40.3 million in 2010 (total population 831.5 million). In general, population ageing has been described as a more recent phenomenon in SSA, causing figures for this region to be well below the global average [1]. However, projections suggest that the gap in life expectancy between SSA and the world average, which was around 20 years in 2010, will drop to 10 years by 2050. By this time, about 7.6% of the SSA population (estimated total 2.074 billion) will be aged 60 years and above, which in absolute number will translate into four times the 2010 estimates, and correspond approximately to 156.7 million people [2].

Figure 1.

Sub-Saharan African countries.

Population ageing is considered a global public health success, but also brings about new health challenges in the form of chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, cancers, as well as neurodegenerative disorders. A characterization and updated picture of the latter conditions in SSA is particularly important in view of a) the ongoing demographic transition and the resulting surge in the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases in SSA; b) the successful roll-out of antiretroviral therapies in the region and the potential, yet unknown impact of long-term survival with HIV infection and related treatments on the occurrence of neurodegenerative disorders [3]; and c) lastly, the need for reliable data for health service planning. Recently, there have been efforts to summarize existing data for conditions like Parkinson disease (PD) [4,5] dementia [6,7] or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [8], but not for other common neurodegenerative disorders, while there are suggestions of possible African distinctiveness in their occurrence and features [9].

We systematically reviewed the published literature on common neurodegenerative disorders and HIV-related neurocognitive impairment among sub-Saharan Africans, with the objective of describing their main features as well as clinical and public health implications.

Methods

Data sources

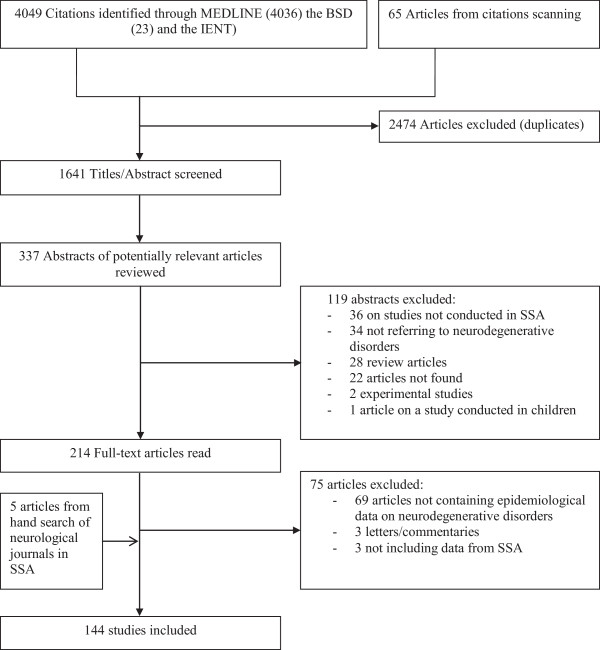

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, and the French database ‘Banque des Données en Santé Publique’ (BDSP http://www.bdsp.ehesp.fr) for articles published until February 2013. In addition we searched the database of the ‘Institut d’Epidemiologie Neurologique et de Neurologie Tropicale’ (IENNT). We used a combination of relevant terms to search (in English for PubMed and in French for BDSP and IENNT), which are presented in Additional file 1 (except for IENNT searches for which we used ‘neuroepidemiologie’ and other themes referring to neurodegenerative diseases). Two evaluators (AL and JBE) independently identified articles and sequentially (titles, abstracts, and then full texts) screened them for inclusion (Figure 2). For articles without abstracts or without enough information in the abstract to make a decision, the full text, and where necessary supplemental materials, were reviewed before a decision was made. We supplemented the electronic searches by scanning the references lists of relevant publications, and identifying their citations through the ISI Web of Science, and by hand-searching all issues of the African Journal of Neurological Sciences. Disagreements were solved by consensus or review by a third investigator (APK).

Figure 2.

Flow of selection of studies for inclusion.

Study selection

We included studies conducted in a country of the SSA region (Figure 1) that reported on the following neurodegenerative diseases among adults: Alzheimer’s disease, fronto-temporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, cortico-basal degeneration, multi system atrophy, Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington disease, cerebellar degeneration, and HIV-related neurocognitive impairment. We made no restriction by study design. We excluded duplicate publications, review articles, studies conducted exclusively in pediatric populations, studies conducted exclusively on migrant populations of African descent living out of the continent. Figure 2 shows the study selection process.

We provide a rigorous appraisal of the overall data and the epidemiological studies in particular, and make recommendations regarding future approaches to measurement, notwithstanding the challenges involved in such undertakings.

Data extraction, assessment, and synthesis

Two reviewers (AL and JBE) independently conducted the data extraction from included studies. We extracted data on study settings, design, population characteristics, measures of disease occurrence (incidence and/or prevalence), and risk factors for the various conditions examined. Given the diversity of neurodegenerative pathologies and the heterogeneity of populations assessed, we did not use a particular framework for the assessment of the quality of studies. However, whenever population-based studies and hospital-based studies had been conducted for a condition, we relied more on the conclusions of population-based studies to address relevant questions, and appropriately reported the results. We conducted a narrative synthesis of the evidence.

Results

The study selection process is shown in Figure 2. A total of 4049 citations were identified through MEDLINE, the IENNT database and BDSP searches; 337 abstracts were evaluated in detail and 214 full-text publications reviewed. The final selection included 144 publications reporting on Parkinsonism (20 studies), dementia (49 publications), HIV-related neurocognitive impairment (47 publications), Huntington disease (19 studies), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (15 studies), cerebellar degeneration (4 studies) and Lewy body dementia (1 study). These studies were published between 1955 and 2012, with about 50% conducted in only two countries: Nigeria and South Africa.

Parkinson disease, other Lewy body diseases and fronto-temporal dementia

Twenty studies reported on Parkinsonism (Table 1), including five community-based and sixteen hospital-based. Four were case–control in design and all the others were cross-sectional studies, including reviews of medical records. These studies were conducted in seven countries including Nigeria (ten studies), South Africa (four studies), Tanzania (two studies), Ethiopia, Ghana, Cameroon and Zimbabwe (one studies each). The number of participants with PD ranged from two to 32 and the prevalence from ten to 235/100,000 in community-based studies. The number of participants with Parkinsonism ranged from four to 397, and the prevalence of Parkinsonism varied from 0.41 to 7.2% of neurological admissions/consultations in hospital-based studies. The proportion of men among those with PD ranged from 53 to 100%, and age ranged from 30 to >100 years. Age at the clinical onset of the disease ranged from 17 to 90 years. The clinical types of the disease were largely dominated by Parkinson disease (38 to 100%).

Table 1.

Overview of studies on Parkinsonism and risk factors in sub-Saharan African countries

| Author, year of publication | Country | Setting | Design/period of study | Population characteristics | Diagnosis criteria | Prevalence | Profile of parkinsonism patients | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bower

[10], 2005 |

Ethiopia |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional 2003-2004 |

720 patients; 109 (15 · 1%) with movement disorders including 71 men; age 52 y. (13–80) |

Not provided |

72/1,000 of all admissions (PD: 64/1,000) |

N:52; PD:88% |

Review of medical files/outpatient neurology clinic. |

| Age (at onset): 57y (30–80) | ||||||||

| Men: 75% | ||||||||

| Akinyemi

[11], 2008 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Case–control 2005-2005 |

51 patients (men 37) with PD and 50 controls |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

NA |

N:51; PD: 100% |

22% patients with PD had cognitive dysfunction, with age at PD onset as sole predictor of cognitive dysfunction. |

| Age (at onset): 70y (41–80) | ||||||||

| Men:72% | ||||||||

| Cosnett

[12], 1988 |

South Africa |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional 1979-1985 |

2638 patients |

Clinical (Bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor and postural instability) |

5.3/1,000 |

N:14; PD: 100% |

Retrospective review of medical files/outpatient clinic |

| Age: NA |

Blacks: 1.5/1000 |

|||||||

| Men: NA |

Indians: 12.6/1000 |

|||||||

| Whites: 23.1/1000 | ||||||||

| Dotchin

[13], 2008 |

Tanzania |

Community |

Cross-sectional |

161,071 inhabitants |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

Overall: 40/100,000 |

N: 32; PD:100% |

Prevalence is adjusted to UK population. Mean duration 5.1 y |

| Men: 64/100,000 | ||||||||

| women: 20/100,000 |

Age (at onset): 69y (29–90) |

|||||||

| Men: 72% | ||||||||

| Schoenberg

[14], 1988 |

Nigeria |

Community |

Cross-sectional |

Black population aged 40 + 3412 participants |

Clinical |

Age adjusted: 67/100,000 |

N: 2; PD:100% |

|

| Age: NA | ||||||||

| Men: NA | ||||||||

| USA |

Community |

Cross-sectional |

Black population aged 40 + 3521 black participants and 5404 white participants. |

Clinical |

Age adjusted: |

N: 12; PD: 100% |

|

|

| Age: NA | ||||||||

| Blacks: 341/100,000 |

Men: NA |

|||||||

| Whites: 352/100,000 | ||||||||

| Winkler

[15], 2010 |

Tanzania |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

n = 8676 patients admitted (740 with neurological diseases) |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

1/1,000 (all patients) |

N: 8; PD:37% |

|

| 2003 |

11/1,000 (Patients with neurological diseases |

|||||||

| Age: ≥32 y | ||||||||

| Men: 100% | ||||||||

| Community |

Cross-sectional |

1569 people, age 50–110 years |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

235/100,000 |

N: 0 |

None of the 18 screened-positive was confirmed as having PD. Poisson distribution used to estimate the prevalence. |

||

| 2003-2005 | ||||||||

| Kengne

[16], 2006 |

Cameroon |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

4041 patients in a neurology clinic145 (3.9%) had neurodegenerative diseases |

Not provided |

488/1,000 of all neurodegenerative diseases; 10.1/1,000 of all neurologic consultation |

N: 41; PD 100% |

4 selected neurodegenerative brain disorders: dementia, PD, ALS, chorea |

| 1993-2001 |

Age: 15-84 y |

|||||||

| Men: 73.2% | ||||||||

| Lombard

[17],1978 |

Zimbabwe |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

Total patients admitted: 83,453 blacks, 34,952 whites |

Not provided |

Blacks: 0.21/1,000 |

N: 50 (17 blacks) |

Retrospective review of medical files |

| Whites: 2.83/1,000 |

Age/men: NA |

|||||||

| Osuntokun

[18], 1979 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

217 patients with parkinsonism |

Not provided |

NA |

N: 217; PD 38% |

All patients evaluated by the authors |

| 1966-1976 |

Age: median 51-70 y, |

|||||||

| Men:75% | ||||||||

| Osuntokun

[19], 1987 |

Nigeria |

Community |

Cross-sectional |

Total participants surveyed: 18,954 |

Not provided |

10/100,000 |

N. 2; PD 100% |

Screening Questionnaire developed by author |

| 1985 |

Age/men: NA |

|||||||

| Haylett

[20], 2012 |

South Africa |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

229 patients with PD including 163 whites (71%), 45 mixed ancestry (20%), 17 blacks (7%) and 4 Indians (2%) |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

NA |

N: 229; PD 100% |

Mutation in the Parkin gene |

| Age (at onset): 54 y (17–80) |

Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations: 7 patients |

|||||||

| Heterozygous variant: 7 | ||||||||

| Men: % NA | ||||||||

| Ekenze

[21], 2010 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

8440 admission in the medical ward; 1249 had neurological diseases (men 640) |

Not specified |

21.9/1000 of al neurological admissions |

N: 14 |

|

| 2003-2007 |

Age ≥ 70 y (71%) |

|||||||

| Men: 28.6% | ||||||||

| Owolabi

[22], 2010 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

6282 admission in the medical ward; 980 had neurological diseases (men 586) |

Clinical: any 3 out of tremor, rigidity, Akinesia/bradikinesia/postural and instability |

4.1/1,000 of all neurological admissions |

N: 4 |

|

| 2005-2007 |

Age: (50–68) |

|||||||

| Men; 100% | ||||||||

| Okubadejo

[23], 2004 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Case–control |

33 participants (men 25, mean age 60 y) with PD and 33 match controls |

Any 3 out of tremor, rigidity, Akinesia/bradikinesia/postural and instability |

NA |

N: 33 |

Case fatality rate was higher in PD (25% vs. 7.1%), Factors associated with increased mortality: advanced age and disease severity |

| Age (at onset): 36-80y | ||||||||

| Men: 75% | ||||||||

| Okubadejo

[24], 2005 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Case–control |

28 participants (men 21, mean age 63 y) with PD and 28 match controls |

Any 2 out of tremor, rigidity, Akinesia/bradikinesia/postural and instability, exclusion of other causes of parkinsonism |

NA |

N: 28; PD 100% |

Autonomic dysfunction rate was higher in PD (61% vs. 6%), |

| Age (at onset): 37-76 y | ||||||||

| Men: 76% | ||||||||

| Okubadejo

[25], 2010 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

124 participants with Parkinsonism in a neurology clinic |

Any 3 of the following: tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural or gait abnormality |

15/1,000 of all neurological consultations |

N: 98; PD 79% |

Other causes of parkinsonism n(%): Vascular/drug induced/MSA/LBD: 9(35)/5(19)/4(15)/3(11) |

| 1996-2006 | ||||||||

| Age (at onset): 61y Men: 76.5% | ||||||||

| Keyser

[26], 2010 |

South Africa |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

154 patients with PD including 51 whites (35%), 45 Afrikaners (31%), 29 mixed ancestry (20%), 17 blacks (12%) and 3 Indians (2%). |

UK Parkinson’s Disease UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

NA |

N: 154; PD 100% |

16 sequence variants of the PINK1gene identified: 1 homozygous mutation (Y258X), 2 heterozygous missense variants (P305A and E476K), and 13 polymorphisms |

| Age (at onset): 52 y | ||||||||

| Men: 62% | ||||||||

| Van Der Merwe

[27], 2012 |

South Africa |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

111 patients with early onset PD (men 71) and 286 with late onset PD (men 62%) from a movement disorder clinic |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

NA |

N: 397; PD 100% |

A positive family history was associated with a younger age at onset. |

| 2007-2011 |

Age (at onset): 57 y Men: 248 |

|||||||

| Femi

[28], 2012 |

Nigeria |

Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

1153 participants in 2 Neurologic clinics; 96 (men: 74) had parkinsonism |

presence of at least three of the four cardinal features of tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural or gait abnormality |

69.4/1,000 of all neurological consultations |

N: 96; PD (83.3%) |

|

| 2007-2011 | ||||||||

| Age: 58 y | ||||||||

| Men: 63.5% | ||||||||

| Cilia

[29], 2012 |

Ghana |

Hospital |

Case–control |

54 participants with PD and 46 healthy participants |

UKPDS Brain Bank criteria |

NA |

N: 54; PD 100% |

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene found in no participants |

| Age (at onset): 59 y (30–83) | ||||||||

| Men: 61% |

NA: Not available; PD: Parkinson’s disease; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; y: years.

The most commonly used tool to diagnose PD was the UKPDS Brain bank criteria and population-based (hospital-based) prevalence for the studies that applied those criteria ranged from 40 to 235/100,000 (11 to 69.4/1,000 neurological consultations). In general risk factors were not investigated across studies, although one study found that 38% of patients with Parkinsonism had atherosclerosis and 8% had encephalitis [18].

We found three cases of Lewy body dementia in a retrospective study in Nigeria, and one case in a retrospective study in Senegal representing respectively 1.2/100,000 of admission over a period of 10 years [30] and 7.5/1000 of participants in a specialized memory clinic [31].

The prevalence of fronto-temporal dementia has been reported in two hospital-based studies conducted in Neuropsychiatric clinics in Nigeria (prevalence rate: 1.7/100,000 of all admissions) and in Senegal (prevalence rate: 7.5/1000 of all participants evaluated for memory impairment) [30,31].

Dementia

(Table 2) summarizes the 49 publications that reported on dementia. These include 18 hospital-based, 30 community-based publications and one publication from a nursing home. Two were case–control in design, seven were cohort-studies and 40 were cross-sectional, including two autopsy studies. These publications reported on studies conducted in eleven countries: Nigeria (33 publications), Senegal (four publications), Kenya and Tanzania (three publications each), Benin, Central African Republic, Congo republic, (two publications each), South Africa, Cameroon and Zambia (one publication each). In addition, there were seven publications on multicenter studies including African American participants in the USA and participants from African countries [32-37]. The overall study size varied from 56 to 2494 in community-based studies and from 23 to 240,294 in hospital-based investigations. The prevalence of dementia ranged from <1% to 10.1% in population-based studies [32,34-57] and from <1% to 47.8% in hospital-based studies [16,21,30,33,38,58-69].

Table 2.

Overview of studies on dementia and risk factors in sub-Saharan Africa

| Author, year of publication | Country/setting | Design/period of study | Population characteristics | Diagnostic criteria | Incidence | Prevalence (%) | Risk factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lambo

[58], 1966 |

Nigeria |

Retrospective/Cross-sectional, 1954-1963 |

328 participants (26% ≥60 y.) |

Not provided |

NA |

Senile dementia*: |

NA |

| Hospital | |||||||

| Overall: 26%, Men: 18.9% Women: 30.5% | |||||||

| 75 cases of dementia (21 men) | |||||||

| Ben-Arie

[39], 1983 |

South Africa |

Cross-sectional, 1982 |

139 participants aged ≥65 y. |

MMSE/ICD-8 codes |

NA |

Any (severe) dementia 8.6% (3.6%) |

NA |

| Community | |||||||

| Makanjuola

[59], 1985 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional 1979-1982 |

51 (5.2% of new consultations); age ≥60 y. |

ICD-9 codes |

NA |

Dementia 11.2% |

NA |

| Hospital | |||||||

| Gureje

[60], 1989 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional, 1984 |

1914 patients; |

ICD- 9 codes |

NA |

No case of dementia |

NA |

| Community | |||||||

| Ogunniyi

[40], 1992 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

930 participants; age ≥40 y. (293 aged ≥65 y.); No case of dementia |

DSM-III-R criteria |

NA |

No case of dementia |

NA |

| Community | |||||||

| Osuntokun

[61], 1994 |

Nigeria, hospital Autopsy study |

Cross-sectional 1986- 1987 |

111 brains autopsied including 85 patients aged ≤60 y. |

Beta A4 amyloid on brain tissues |

NA |

Heavy/moderate/mild plaque load: 0/6.3/18.9% |

NA |

| Osuntokun

[41], 1995 |

Nigeria, community |

Cross-sectional |

56 subjects (17 with dementia and 12 with AD); age ≥65 y. |

Dementia –CSID |

NA |

APOE ϵ4 allele in dementia/AD/controls 17.6/16.7/20.5%. |

NA |

| AD - NINCDS-ADRDA criteria | |||||||

| Osuntokun

[38], 1995 |

Nigeria, hospital Autopsy study |

Cross-sectional |

198 brains were autopsied |

senile plaque, neurofibrillary tangle, and amyloid vascular degeneration |

NA |

No evidence of NFT or senile plaque |

NA |

| 1986- 1987 |

Including 45 (23%) ≥65 year |

||||||

| Hendrie

[32], 1995 |

Nigeria, community |

Cross-sectional |

2494 participants, age ≥65 y., Dementia -28, AD - 18, VaD - 8. |

Dementia: CSID/DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria |

NA |

Dementia - Overall/65-74/75-84/≥85 y: |

|

| 1992-1993 |

2.3/0 · 9/2.7/9.6; |

||||||

| AD - 1.4/0.5/1.7/5.9% | |||||||

| Indianapolis-USA, community & nursing home |

Cross-sectional |

2212participants, aged ≥65 y. (community) and 106 (nursing home) |

Dementia: CSID/DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA criteria |

NA |

Dementia Overall/65-74/75-84/≥85 y: |

NA |

|

| 1992 - 1993 | |||||||

| 8.2/2 · 6/11.4/32.4% | |||||||

| AD -6.2/1.6/8.0/28.8% | |||||||

| Ogeng'o

[33], 1996 |

Tanzania, hospital |

Cross-sectional |

12 Non-demented subjects aged 45–83 y. |

senile plaque, neurofibrillary tangle, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

NA |

Amyloid β plaques:17% |

NA |

| 1996 |

Autopsy study |

||||||

| Neurofibrillary Tangles: 17%; Cerebral Amyloid angiopathy: 17% | |||||||

| Kenya, hospital |

Cross-sectional Autopsy study |

20 Non-demented subjects aged 45–70 y. |

Senile plaque, neurofibrillary tangle, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

NA |

Amyloid β plaques: 15%; Neurofibrillary Tangles: 15%; Cerebral Amyloid angiopathy: 15% |

NA |

|

| USA-Cleveland, Hospital |

Cross-sectional/Autopsy study |

20 Non-demented subjects aged 48–84 y. |

Senile plaque, neurofibrillary tangle, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

NA |

Amyloid β plaques: 20%; Neurofibrillary: 15%; Cerebral Amyloid angiopathy: 20% |

NA |

|

| Ogunniyi

[42], 1997 |

Nigeria, community |

Cross-sectional |

2494 participants aged >65 y screened, 28 with dementia. |

Screening: CSI-D) |

NA |

Any/ AD/ vascular dementia - 1.1/0.7/0.3% |

N A |

| 1992-1994 | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-III-R and ICD-10 codes | |||||||

| AD: NINCDS-ADRDA | |||||||

| Sayi

[62], 1997 |

Tanzania, hospital |

Cross-sectional |

24 demented and 286 non-demented participants aged 50–89 y. |

Swahili modified MMSE |

NA |

Prevalence of ϵ4 allele of APOE: Demented - 25%; non demented - 21% |

NA |

| Kenya, hospital |

Cross-sectional |

22 demented and 60 non-demented participants aged ≥65 y. |

Swahili modified MMSE |

NA |

Prevalence of ϵ4 allele of APOE: Demented - 42%, non-demented - 27% |

NA |

|

| Baiyewu

[63], 1997 |

Nigeria, Nursing home |

Cross-sectional |

23 participants (in a nursing home) aged 66–102 y.; 11 women |

DSM-III-R/AGECAT |

NA |

Any dementia (AD) - 47 · 8% (26 · 1%) |

NA |

| 1994 | |||||||

| Hall

[34],1998 |

Nigeria, community |

Case–control |

2494 participants; age ≥ 65 y.; |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

18 cases of possible or probable AD1.4% |

age (OR = 1.15; 95% |

| 423 clinically assessed after screening, | |||||||

| CI = 1.12-1.18) and female gender (OR = 13.9; 95% CI = 3.85-50.82) | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA | |||||||

| USA–Indianapolis, community |

Case–control |

2212 participants; age ≥ 65 y.; |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

Possible/probable AD 6.2% |

age, family history of dementia, education; rural residence |

|

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA | |||||||

| 351 clinically assessed after screening,; 49 (men 17) diagnosed with AD | |||||||

| Uwakwe

[70], 2000 |

Nigeria, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

119 participants; age ≥65 y; 3 had dementia |

Geriatric Mental State and/ICD-10 |

NA |

2.8% |

NA |

| 1995-1996 | |||||||

| Ogunniyi

[43], 2000 |

Nigeria, community |

Cross-sectional 1992-1994 |

2494 participants, age ≥65 y.; 28 with dementia (men: 8) including 18 with AD, 8 with vascular dementia |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

Any dementia 2.3% |

Age (OR: 1.15), female gender (13.9), living with others (OR: 0 · 06) |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

AD: 1.4% |

||||||

| E4 allele in AD (normal subjects) 34.2% (21.8%) | |||||||

| Indianapolis-USA, community |

Cross-sectional |

2212 participants, age ≥65 year; 65 with dementia including 49 with AD, 10 with vascular dementia |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

Dementia (AD) overall/65-74/75-84/≥85 y – 8.2 (6.2)/2.62 (1.58)/ 11.4 (8.0)/32 · 4% (28.8%); |

Age, rural residence, family history of dementia, education |

|

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| 1992-1994 | |||||||

| AD: NINCDS-ADRDA | |||||||

| Hendrie

[35], 2001 |

Nigeria, community |

Prospective cohort Baseline survey in 1992-1993 |

2459 participants included after the first visit; 1303 (men 461) completed the follow-up; age ≥65 y. |

Screening: CSID |

Dementia: 13.5/1,000 |

NA |

NA |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

AD: 11.5/1000 |

||||||

| USA-Indianapolis, community |

Prospective cohort |

2147 African-Americans included after the first visit; 1321 (men 417) completed the follow-up; age ≥65 y. |

Screening: CSID |

Dementia (AD) |

NA |

NA |

|

| Baseline survey in 1992-1993 | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA | |||||||

| 32.4/1,000 (25.2/1,000) | |||||||

| Baiyewu

[44], 2002 |

Nigeria, community |

Prospective cohort baseline survey in 1992-1993 |

2487 participants; age ≥65 y.; |

Screening: CSID |

Conversion from CIND to dementia 16 · 1%; From CIND to normal 25 · 3% |

NA |

Sex |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| 423 clinically assessed after screening; 152 diagnosed with CIND; 28 (men 7) with dementia, 87 followed up for 2 years. | |||||||

| Perkins

[36], 2002 |

Ibadan-Nigeria community |

Prospective, 1992-1993 |

2487 participants; age ≥65 y; |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

1.8% |

Dementia associated with mortality |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| 423clinically assessed after screening | |||||||

| Indianapolis-USA, Community |

Prospective Baseline survey in 1992-1993 |

2212 participants; aged ≥65 y.; |

Screening: CSID |

|

4.9% |

Dementia associated mortality (adjusted RR: 2 · 05) |

|

| 342 clinically assessed after screening | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| Lane

[37], 2003 |

Nigeria Community |

Prospective 8.7 y follow up Baseline 1992-1993 |

968 participants (271 aged ≥75 y.); |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

NA |

ApoEϵ4 alleles not associated with increased mortality |

| 23with dementia at follow-up | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| Indianapolis-USA, Community |

Prospective 9.5 y. Baseline 1992-1993 |

353 participants (17 4 aged ≥75 y.); 17 with dementia at follow-up |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

NA |

ApoEϵ4 associated with increased mortality for patient under 75 year |

|

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| Ogunniyi

[45], 2005 |

Nigeria, Community |

Cross-sectional/1992- 1998 |

98 demented subjects; age ≥65 y. |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

AD: 82% of all cases |

NA |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| VaD: 11.1% of all cases | |||||||

| Kengne

[16], 2006 |

Cameroon, |

Cross sectional, |

4041 neurologic consultations |

Not provided |

NA |

0.4% (all neurologic admission), 19% (neurodegenerative diseases) |

NA |

| Hospital |

1993-2001 |

||||||

| 145 with neurodegenerative diseases | |||||||

| 16 (men 14) with dementia, mean age 67.8 y. | |||||||

| Gureje

[46], 2006 |

Nigeria, Community |

Cross-sectional, 2003-2004 |

2152 participants at baseline with a respondent rate of 74% (1904 participants). Aged 65 year or older. |

adapted 10-Word Delay Recall Test (10-WDRT)10 |

NA |

Overall: 10.1%; |

Female gender, Increasing age, alcohol |

| Female: 14.6% | |||||||

| Men: 7.0% | |||||||

| Gureje

[71], 2006 |

Nigeria Community |

Cross-sectional, |

2245 DNA samples, 830 had a diagnosis |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

Any dementia (16.9% |

E4 allele in AD (normal subjects) 26 · 0% (21 · 7%) |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| AD: 14.8% | |||||||

| Ogunniyi

[72], 2006 |

Nigeria, Community |

Case–control |

62 participants with AD (Men 16.1%, mean age 82 y) and 461 non demented (men 33.2%, mean age 77 y) |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

|

Age (OR 1 · 07) |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA | |||||||

| Rural to age (OR 2 · 93) Hypertension (OR 0 · 33) | |||||||

| Indianapolis-USA, Community |

Case–control |

89 participants with AD (men 30.3%, mean age 83 y), mean age 77 y) and 381 non demented (Men 31.2%, mean age 78 y) |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

|

Age (OR 1.09 |

|

| Rural to age (OR 2.08) | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

Alcohol consumption (OR 0.49) |

||||||

| Uwakwe

[64], 2006 |

Nigeria, Community |

Cross-sectional |

30 patients (men 12) with dementia and their caregivers (total 30) |

Not provided |

NA |

N:52; |

|

| 2003-2005 | |||||||

| AD: not provided | |||||||

| Men: 12 | |||||||

| Ochayi

[47], 2006 |

Nigeria, Community |

Cross-sectional 2002 |

280 participants; age ≥65 y.; |

CSID |

NA |

Overall dementia: 6.4% |

Female gender, |

| Lower body mass index, age, NSAIDS | |||||||

| 65-74 year old: 5.2% | |||||||

| 18 (men 2) with dementia |

≥85 year 16%. |

||||||

| Hall

[48], 2006 |

Nigeria, Community |

Cross-sectional |

1075 participants; age ≥ 70 y. 29 (men 5) with AD, |

NINCDS-ADRDA |

NA |

NA |

Total- or LDL- cholesterol in individuals without the APOE-ϵ4 allele |

| Uwakwe

[73], 2009 |

Nigeria, community |

Cross-sectional |

914 (men 432) participants, age ≥65 y; 87 with ≥2 tests memory tests impaired |

Memory impairment assessed by MMS, CISD and 10 word list immediate and delayed recall |

NA |

9.9% |

NA |

| Guerchet

[50], 2009 |

Benin Community |

Cross-sectional |

502 (men 156) participants, aged ≥65 y; 52 with cognitive impairment |

Screening: CSI-D |

NA |

Cognitive impairment |

Age, current depressive disorder, absence of the APOE ϵ 2 |

| Overall: 10.4%; men 7.7 women 11.5% | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-IV | |||||||

| AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

|

Dementia Overall: 2.5%, men 0.6% women 3.4% |

|||||

| 13 (men 1) with dementia | |||||||

| Toure

[67], 2009 |

Senegal |

Cross-sectional |

872 participants; age ≥55 y. |

DSM-IV-R |

NA |

Overall 6.6% |

Age, social isolation, history of stroke, epilepsy, family history of dementia, Parkinson’s disease |

| Hospital |

2004-2005 |

58 cases of dementia |

|||||

| Napon

[68], 2009 |

Burkina Fasso |

Cross-sectional |

15815 (2396) out (in) participants; age ≥15 y.; 72 (and 53 inpatients) with dementia; AD: 7; VaD: 19 cases |

DSM-IV |

NA |

outpatients: 0.45% inpatients: 0.22% |

NA |

| Hospital | |||||||

| Guerchet

[49], 2010 |

Central African Republic Community |

Cross-sectional |

509 interviewed; 496 (men 218) included in final sample, age ≥65 y. |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

Overall: 8.1%, men 2.7%, women 12.2% |

NA |

| 2008-2009 | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-IV | |||||||

| 188 with cognitive impairment and 40 (men 6) with dementia (mean age 76 y.); 33 (men 3) with AD and 7 (men 2) with VaD |

AD: NINCDS-ADRDA Hachinski scale, |

||||||

| Republic of Congo Community |

Cross-sectional |

546 interviewed; 520 (men 198) included in final sample, age ≥65 y. 148 with cognitive impairment and 35 (men 9) with dementia (mean age 79 y.); 24 (men 7) with AD and 11 (men 3) with VaD |

CSID/ DSM-IV and NINCDS-ADRDA Hachinski scale |

|

Overall: 6.7%, men 4.5%, women 8.1% |

NA |

|

| 2008-2009 | |||||||

| Chen

[65], 2010 |

Kenya |

Cross-sectional |

100 participants; age ≥ 65 y. |

CSI-D using a version in Kikuyu. |

NA |

Apo ϵ4 allele frequency: |

NA |

| Hospital | |||||||

| Demented 31.3%, non-demented 32.2% | |||||||

| 84 controls (men 38) and 16 with dementia participants (men 7) | |||||||

| Ekenze

[21], 2010 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

8440 admissions; 1249 (men 640) with neurological diseases (age range18-83 y.); 38 (men 23) with dementia |

Not specified |

NA |

3% |

NA |

| Hospital |

2003-2007 |

||||||

| Siddiqi

[69], 2009 |

Zambia |

Cross-sectional |

443 inpatients (men 219); median age 39 y., 67 with HIV; 368 outpatients (men 168); median age 39 y., 58 with HIV; 36 with dementia |

Not specified |

NA |

Dementia: |

Dementia in HIV + patients 8 (13.8%) vs. general population 9 (2.9%) (p = 0.002) |

| Overall: 4.4% | |||||||

| Hospital |

2006 |

||||||

| Yusuf

[74], 2011 |

Nigeria Community |

Cross-sectional |

322 participants (men 128); mean age: 75.5 y |

Screening: CSID/CERAD/SDT |

NA |

Dementia: 2.8% |

Age |

| AD: 1.9% | |||||||

| VaD: 0.6% | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-IV and ICD-10 | |||||||

| 9 cases of dementia (men 3); mean age: 82.4 y |

LBD: McKhan clinical criteria |

||||||

| FTD: McKeith clinical criteria | |||||||

| Gureje

[51], 2011 |

Nigeria, Community |

Prospective Cohort Baseline 2003-2004 |

2,149 participants at baseline |

10-Word Delayed Recall |

21.80/1,000 |

NA |

Poor social engagement, rural residence, low economic status, female gender, age. |

| Test (cut off of 18) | |||||||

| 1,408 at 39 months follow-up; 85 (among ≥65 y.) developed dementia | |||||||

| Ogunniyi

[52], 2011 |

Nigeria Community |

Cohort study |

1559 participants aged > 65 year without dementia a baseline. 136 (men 33) with dementia (mean age 83.1 y.) at follow-up; 255 with MCI |

Dementia: DSM-III-R and ICD-10 |

Dementia: 8.72/1,000/year |

NA |

Low BMI |

| 1992-2007 |

MCI: 16.35/1000/year |

||||||

| Ogunniy

[53], 2011 |

Nigeria Community |

prospective cohort baseline 1992 |

2718 participants interviewed |

Dementia: DSM-III-R and ICD-10 |

Dementia/AD/VaD (per 1,000/year) 11.50/9.50/1.10 |

NA |

Higher SBP, DBP and PP |

| 1753 (age ≥65 y.) in the final sample | |||||||

| 120 (men 30) with dementia (mean age 83.8 y.); 99 with AD; 11 with VaD | |||||||

| Paraïso

[56], |

Benin Community |

Cross-sectional |

1,139 (men 523) participants; age ≥65 y.; 42 (men 13) with dementia (mean age 79 · 1 y) |

Screening: CSI-D |

NA |

Dementia Overall 3.7% men 1.1% women: 2.5% |

NA |

| 2011 | |||||||

| 2008 | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-IV | |||||||

| 32 with AD, 105 with CIND | |||||||

| AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

|

AD Overall 2.8% |

|||||

| VD Overall 0.8% | |||||||

| VaD: NINCDS-AIREN | |||||||

| Amoo

[30], |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

240,294 participants |

Dementia: ICD-10 |

NA |

Dementia: 45/100,000 |

NA |

| 2011 | |||||||

| AD; 25 · 8/100,000 | |||||||

| Hospital |

1998-2007 |

VaD: 7 · 4/100,000 |

|||||

| 108 (men 51) with dementia (mean age: 70.1); 62 (men 24) with AD; 18 (men 13) with VaD; 4 (men 2) with mixed forms; |

ADNINCDS – ADRDA |

||||||

| VaD: NINCDS –AIRENS | |||||||

| LBD: McKeith criteria, | |||||||

| FTD: Lund and Manchester Criteria | |||||||

| 4 (men 2) with FTD; 3 (men 0) with DLB; 13 (men 2) with unclassified dementia | |||||||

| Ndiaye

[31], 2011 |

Senegal |

Cross-sectional |

132 patients seen at a memory clinic (men 41, mean age: 67 y |

Screening: “Test du Senegal”/modified HodKinson test |

NA |

MCI: 14.4% |

NA |

| Hospital | |||||||

| 2004-2005 | |||||||

| 57 with dementia; 37 with AD, 10 with VaD, 5 with FTD and 1 with LBD. |

Dementia: 43.2% |

||||||

| AD: 64.7% of all cases of dementia | |||||||

| MCI: Petersen criteria | |||||||

| Dementia: DSM-IV | |||||||

| Coume

[75], 2012 |

Senegal |

Cross-sectional |

872 (men 546) participants aged >55 y; mean age 67 · 2 y |

Test du Senegal |

NA |

Cognitive impairment 10.8% |

NA |

| Hospital |

2004-2005 |

94 (men 65) with cognitive impairment (74 aged > =65 y) |

|||||

| Baiyewu

[54]., 2012 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional/2001 and 2004 |

21 (men 4) participants with normal cognition (mean age 82.8 y.) |

Screening: CSID |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Dementia: DSM-III-R/ICD-10 | |||||||

| Community |

53 (men 4) with cognitive impairment (mean age 80.9); 34 (men 6) with dementia (mean age 83.3 y) |

AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

|||||

| Toure

[66], 2012 |

Senegal |

Cross-sectional |

507 participants; age ≥65 y. |

Screening: Aging in Senegal Questionnaire |

NA |

8.9% |

advanced age (Age ≥80 y, OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.4-13), illiteracy, epilepsy, family history of dementia |

| 45 with dementia |

DSM-IV-R |

||||||

| Hospital |

2004-2005 |

||||||

| Longdon

[57], 2012 |

Tanzania |

Cross-sectional |

1198 (men 525) participants; age ≥70 y; 78 with dementia |

Screening: CSI-D |

NA |

6.4% |

Advanced age |

| Community |

2010 |

||||||

| DSM-IV-R | |||||||

| Onwuekwe

[76], 2012 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

135 participants (men: 79), aged between 16–76 y |

MMSE (cut off of 17 for MCI) |

NA |

MCI: 5.9% |

|

| Hospital |

2004 |

||||||

| 8 with MCI | |||||||

| Guerchet

[55], 2012 |

Central African Republic, Congo |

Cross-sectional |

509 interviewed; 496 (men 218) included in final sample; age ≥65 y.; 188 with cognitive impairment |

Dementia: DSM-IV-R/AD: NINCDS-ADRDA |

NA |

Dementia: 7.4% |

Hypertension, low BMI, depressive symptoms, change of residence, age (OR 2.59, 95% CI, early death of one parent, female gender |

| 2008-2009 | |||||||

| Community |

AD: 5.6% |

||||||

| 546 interviewed; 520 (men 198) included in final sample; age ≥65 y.; 148 with cognitive impairment | |||||||

| Overall 75 (men 15) had dementia 18 with vascular dementia |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; ICD: International Classification of Disease; BMI: Body Mass Index; CI: confidence Interval; CIND: Cognitive Impairment and No Dementia; CSID: Community Screening Interview for Dementia; DSM-III-R: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 3rd edition revised; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; NA: Not available; NFT: Neurofibrillary tangle; NINCDS/ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; OR: Odd ratio; SCEB: short cognitive evaluation battery; USA: United States of America; VaD: Vascular dementia; y: years.

The proportion of men among those with dementia was 7.1 to 69.1%. The mean age of participants ranged from 70.1 to 83.8 years. When provided, age at clinical diagnosis of disease ranged from 80.7 to 83.8 years. Alzheimer disease was the most common form of the disease, representing 57.4 to 89.4 % of all cases [30-32,34,42,45,55,56,63,71,74], followed by vascular dementia 5.7 to 31.0% of cases [30,31,45,56,74]. Four publications in Nigeria provided incidence data for dementia ranging from 8.7 to 21.8 cases per 1000 per year [35,51-53]. Incidence of Alzheimer disease ranged from 9.5 to 11.5 per 1000 per year [35,53].

The most commonly used tool for dementia screening was the Community Screening Interview for Dementia (CSID) questionnaire applied in 20 publications [32,34,36,37,41-43,45-47,49,50,54,56,65,70]. The diagnosis of dementia mainly relied on the DSM-III-R/DSM-IV and ICD-10 classification [30,32,34-37,40,42-46,52-54,63,70]. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease was based on the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria [30,32,34,35,41,43,48,50,52-56,75]. Population-based studies that used DSM-III/DSM-IV and ICD-10 for dementia reported prevalences ranging from 1.1 to 8.1% [32,35,42,49,55-57,65,67,74] (ref 13, 16, 23, 30, 36–38, 48, 50, 118). Likewise the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease ranged from 0.7 to 5.6% based on NINCDS/ADRDA criteria [35,42,55].

Risk factors for dementia were reported in 14 publications. The following were associated with an increased risk of dementia: age (twelve publications), female sex (five publications), low body mass index (three publications), anxiety/depression (three publications), hypertension (three publications), social isolation (two publications), lifetime history of alcohol consumption, elevated total- or LDL cholesterol in those without Apo E ϵ4 (one publication), low socio-economic status, history of stroke and family history of dementia (one publication). The following characteristics were inversely associated with dementia: living with others, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and absence of Apo E ϵ2. Some risk factors were more strongly related to the disease. These include age, which increased the risk of dementia by five to 16% across groups [34,43], but this effect was much higher after the age of 60 years, more than 100% increase risk especially after the age of 75 [46,50,51,55,66,67]. Female sex, low level of education (<6 years), rural residence and family history increased the risk of dementia by >100% [34,43,46,55,56,66].

HIV-related neurocognitive impairment

Fifty-one hospital-based studies (47 publications) reported on HIV-related neurocognitive impairment (Table 3), of which ten were case–control, six cohort and 31 cross-sectional. These studies were conducted in 14 countries including South Africa (14 studies), Uganda (eight studies), Nigeria (six studies), Zambia and Kenya (four studies each), Cameroon and Democratic republic of Congo (three studies each) Ethiopia and Malawi (two studies each), Central African Republic, Botswana, Guinea Bissau, Tanzania and Zimbabwe (one study each). A total of 33 out of the 47 selected publications were published during the last 5 years and only 7 before 2000. The absolute number of participants with HIV-related dementia ranged from 0 to 396, with a prevalence ranging from 0% to 80%.

Table 3.

Overview of studies on HIV-related dementia and risk factors in sub-Saharan

| Author, year of publication | Country/setting | Design/study period | Population characteristics | Diagnostic criteria | Prevalence | Risk factors | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belec

[77], 1989 |

Central African republic, Hospital |

Cross-sectional 1987 |

93 HIV + participants; age and sex not specified |

Not reported |

HAND: 3 cases (3.2%) |

NA |

No neuro-imaging or neuropathological studies |

| Howlet

[78], 1989 |

Tanzania, hospital |

Cross-sectional 1985-1988 |

200 (men 129) HIV + participants; mean age: 32 y |

Decline of memory and other functions |

Dementia complex: 54% |

NA |

|

| Turnbull

[79], 1991 |

South Africa |

Cross-sectional 1982-1983 |

27 haemophilic patients with HIV infection |

Battery of neuropsychological tests: Rey complex figure, Babcock story, digit span, WAIS |

HAND: 4 cases (14.8%) |

NA |

|

| Perriëns

[80], 1992 |

Democratic republic of Congo Hospital |

Cross sectional 2008 |

104 (men 48) HIV + participants; mean age: 34.3 y.; 92 (men 53) HIV- participants; mean age 44 y 9 (men 5) HIV + with HAND |

WHO operational criteria/American Academy of neurology criteria |

HIV Associated |Dementia Complex. 8.7% |

NA |

No neuro-imaging study |

| Maj

[81], 1994 |

Kenya Hospital |

Cross sectional 1990-1991 |

65 (men 49) HIV- participants; mean age: 30 y.; 66 (men 42) asymptomatic HIV + participants; mean age 30.7; 72 (men 48) symptomatic HIV + participants; mean age: 33.2 y |

ICD-10/DSM-IV |

Dementia HIV- 0 Asymptomatic HIV + 0 Symptomatic HIV + 6 (%) |

NA |

|

| Democratic republic of Congo Hospital |

85 ( men 48) HIV- participants; mean age: 33.9 y; 52 (men 33) asymptomatic HIV + participants; mean age 32.3 y.; 68 (men 35) symptomatic HIV + participants; mean age: 33.8 y |

ICD-10/DSM-IV |

Dementia HIV- 0 Asymptomatic HIV + 0 Symptomatic HIV + (5.9%) |

NA |

|

||

| Carson

[82], 1998 |

Kenya |

Cross sectional |

78 (men 52) HIV + participants; mean age: 29.9 y.; 138 (men 114) HIV- participants; mean age 29.8 y. |

Revised WAIS, Trails A and Trails B tests, Digit span, Delayed word and d recognition |

NA |

NA |

No difference in neuropsychiatric test performance between HIV + and HIV- |

| Hospital |

1994 |

||||||

| Sebit

[83], 1995 |

Kenya |

Cross sectional |

191 participants, 72 (men 48) symptomatic HIV + (mean age 33.2 y.), 66 (men 42) asymptomatic HIV + (mean age 30.7) and 65 (men 49) HIV- (mean age 30 y.) |

WHO operational criteria/American Academy of neurology criteria |

Mental disorders: |

NA |

No specific data for HIV associated neurocognitive disorders |

| Hospital | |||||||

| 1990-1991 | |||||||

| Symptomatic HIV + 7.1%, Asymptomatic HIV + 4.5%, HIV -0 | |||||||

| Democratic republic of Congo (DRC)/Hospital |

190 participants, 68 (men 35) symptomatic HIV + (mean age 33.8 y.), 52 (men 33) asymptomatic HIV + (mean age 32.3) and 85 (men 48) HIV- (mean age: 33.9 y.) |

WHO operational criteria/American Academy of neurology criteria |

Mental disorders: |

NA |

No specific data for HIV associated neurocognitive disorders |

||

| symptomatic HIV + 5.9%, asymptomatic HIV + 1.9%, HIV– 1.2% | |||||||

| Sacktor

[84], 2006 |

Uganda, Hospital |

Prospective |

23 (men 5) HIV + participants on |

MSK HIV dementia scale IHDS |

Baseline: Subclinical dementia 35% |

NA |

All participants had CD4 count ≤200 cells/mL and an IHDS ≤ 10 (suggestive of HAND) |

| Cohort study | |||||||

| 2004-2005 | |||||||

| HAART (mean age 32.8 y.) | |||||||

| Re-assessment at 3 and 6 months. | |||||||

| Mild dementia 61% | |||||||

| At 3 (6) months: mild dementia 26% (4%) | |||||||

| Sacktor

[85], 2005 |

Uganda, Hospital |

Cross-sectional 2003-2004 |

81 HIV+; mean age: 37 y.; 100 HIV- mean age: 31.4 y; 21 had HIV dementia |

IHDS (cut off ≤10), |

HIV dementia: 31% |

NA |

|

| MSK HIV dementia scale | |||||||

| Modi

[86], 2007 |

South-Africa, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

506 HIV + (men 203) on HAART; mean age/range: 37 years 193 had HIV associated dementia |

American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task force |

HIV dementia: 38% |

NA |

75% had CD4 below 100 cells/mm3 |

| 2005 | |||||||

| Clifford

[87], 2007 |

Ethiopia, Hospital |

Case–control |

73 (men 67%) HIV + participants (median age 39 y.); |

IHDS |

NA |

NA |

Quantitative neuropsychiatric tests - no difference between groups |

| 2004 | |||||||

| 87 (men 63%) HIV- participants (median age 38 y.) | |||||||

| Odiase

[88], 2007 |

Nigeria, Hospital |

case–control |

96 (men 48) symptomatic HIV + patients (mean age 33.6 y.), |

FePsy computerized neuropsychological test battery |

NA |

NA |

Severity of immune suppression predictive of cognitive decline |

| 2004 | |||||||

| 96 (men 48) asymptomatic HIV + (mean age 31.5 y.); 96 (men 48) HIV- (mean age 32.9 y.) | |||||||

| Wong

[89], 2007 |

Uganda, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

78 (men 28) HIV + participants (mean age 37 y.); 24 (men 6) with dementia; 100 HIV – participants |

MSK HIV dementia scale |

HIV dementia. 31% |

Age, low CD4 count associated HIV dementia |

|

| 2003-2004 | |||||||

| Robertson

[90], 2007 |

Uganda, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

110 (men 34) HIV + participants (WHO Stage 2/3/4, n = 21/69/20); mean age 36.7 y.; 49 on HAART |

MSK HIV dementia scale |

NA |

NA |

Pattern of neuropsychological deficits similar to that in western countries. |

| 2003-2004 | |||||||

| 100 (men 60) HIV– controls (mean age 27.5 y.) | |||||||

| Salawu

[91], 2008 |

Nigeria, hospital |

Cross-sectional |

60 HIV + (men 24), asymptomatic, naïve of HAART; mean age 32 y) |

CSID |

56.7% |

No correlation between CD4 count and performance on neuropsychological testing |

|

| 60 HIV- (men 24); mean age: 30.1 y; | |||||||

| 34 had HIV dementia | |||||||

| Singh

[92], 2008 |

South Africa, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

20 HIV + (men 8) participants; median age 34 y |

IHDS-criteria (cut-off ≤10) |

HAND: 80% |

NA |

CD4 < 200 cells/mm3, older than 18 years and not be delirious. |

| 2007 |

16 had HAND |

||||||

| Säll

[93], 2009 |

South Africa, Hospital |

Retrospective |

38 HIV + admitted to the psychiatric ward with psychiatric symptoms; mmean age 32.4 y |

DSM-IV |

Dementia: 32% |

NA |

|

| 1987-1997 | |||||||

| 12 had dementia | |||||||

| Ganasen

[94], 2008 |

South Africa, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

474 (men 123) HIV + patients (328 blacks and 135 coloured); mean age 34 y. |

HIV dementia scale |

HAND: 17.1% (IHDS) and 2.3% (MMSE) |

NA |

|

| MMSE | |||||||

| Njamnshi

[95], 2008 |

Cameroon, Hospital |

Case–control study 2006 |

204 (men 64) HIV + participants (mean age 37.2 y.); 204 (men 64) HIV- participants (mean age 37.1 y.) |

IHDS-criteria (cut-off ≤10) |

HAND: |

NA |

|

| HIV+: 21.1% | |||||||

| HIV-: 2.5% | |||||||

| Sacktor

[96], 2009 |

Uganda, Hospital |

Prospective cohort |

102 (men 29) HIV + never treated patients (mean age 34.2 y.) started on Stavudine-based HAART |

IHDS criteria |

Base line: 40% had HIV dementia (33% mild, 7% moderate) |

NA |

|

| MSK HIV dementia scale | |||||||

| 2005-2007 | |||||||

| Follow-up 6 months | |||||||

| 25 (men 15) HIV- (mean age 30.3 y.) | |||||||

| At 3 months: 26%, 23% mild, 3% moderate | |||||||

| At 6 months: 16% (13% mild, 3% moderate | |||||||

| Njamnshi

[97], 2009 |

Cameroon, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

185 (men 61) HIV + participants (mean age 37 y.); 41 with possible HAND (mean age 37y.) |

IHDS-criteria |

HAND: 22. 2% |

Advanced clinical stage, low CD4 count, and low haemoglobin levels |

|

| 2006 | |||||||

| Sacktor

[98], 2009 |

Uganda, |

Cross-sectional |

60 HIV + never treated participants; 22 with dementia |

IHDS criteria |

Overall: 36.7% |

HIV subtype D associated with increased risk of HIV dementia |

All participants had CD4, count ≤200 cells/mL and an IHDS ≤ 10 (suggestive of HAND) |

| Hospital | |||||||

| 2005-2007 | |||||||

| MSK HIV dementia scale | |||||||

| Nakasujja

[99], 2010 |

Uganda, |

Prospective cohort |

102 HIV + (men 28); mean age: 34.2 y; 70 with cognitive impairment at baseline |

IHDS (cut-off ≤10) |

Base line: 68.6% |

NA |

|

| Hospital | |||||||

| 2005-2007 | |||||||

| neuropsychological tests and MSK HIV dementia scale |

At 3 months: 36% |

||||||

| At 6 months: 30% | |||||||

| Kinyanda

[100], 2011 |

Uganda, |

Cross-sectional |

618 HIV + (men 169), 83% <45 y |

IHDS (cut-off ≤ 10) |

64% |

|

|

| 396 had cognitive disorders | |||||||

| Hospital |

2010 |

||||||

| Choi

[101], 2011 |

Guinea Bissau, |

Case–control |

22 HIV-2 + (men 4)participants mean age for those with CD4 < 350 = 55.1 y, mean age for those with CD4 ≥ 350 = 50.3 y) |

IHDS |

HIV+: 22.7% (CD4 < 350 = 27%, CD4 ≥ 350 = 18%) |

age (β = -0.11) |

|

| Hospital | |||||||

| 45 HIV- controls (men 1); mean age51 · 9 y) |

MSK HIV dementia scale |

||||||

| Control: 11% | |||||||

| Birbeck

[102], 2011 |

Zambia,, |

Cross-sectional |

496 HIV + (men 205) participants screened within 1 week of initiating ART; mean age 38.1 y) |

I\HDS (cutt-off ≤ 10) |

42.1% (IHDS) |

NA |

Low IHDS score was associated with poor adherence to HAART |

| Hospital |

2006-2007 |

||||||

| MMSE (<=22) |

34.4% (zMMSE) |

||||||

| IHDS administered to 440 participants. | |||||||

| 185 had dementia | |||||||

| Joska

[103], 2010 |

South Africa, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

536 (men 26.7%) HIV + participants (68% blacks, 28% coloured), mean age 34 y. |

HDS (cutt-off ≤ 10) |

HAND: 23.5% |

Age, education, diagnosed duration, post-traumatic stress disorder |

IDHS not yet available by the time of the study |

| Kanmogne

[104], 2010 |

Cameroon |

Case–control |

43 (men 18) HIV- participants (mean age 33.3 y.); 44 (men 17) HIV + participants (mean age 34.9 y.); 22 with AIDs defining conditions, 34% on HAART |

HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center International neuropsychological test battery |

NA |

NA |

|

| Hospital | |||||||

| 2008-2009 | |||||||

| Lawler

[105], 2010 |

Botswana, |

Cross-sectional |

120 (men 60) HIV + patients (mean age 37.5 y.); 97.5% on HAART; |

IHDS-criteria (cut-off ≤9.5) |

HAND: 38% |

NA |

|

| 2008 |

46 with HIV dementia |

||||||

| Hospital | |||||||

| Patel

[106], 2010 |

Malawi, Hospital |

Cross sectional |

179 (men 63) HIV + participants (mean age 36.7 y.); Stage III/IV 90%; 134 on HAART > 6 months; |

IHDS-criteria (cut-off ≤10) |

HAD |

Female gender, low education |

|

| 2007 | |||||||

| 25 (men 14) with HIV dementia | |||||||

| Overall: 14% | |||||||

| Men: 22.2% | |||||||

| Women: 9.5% | |||||||

| Siddiqi

[69], 2009 |

Zambia |

Cross-sectional |

443 (men 219) inpatients (median age 39 y., 67 HIV+); 368 (men 168) outpatients (median age 39 y., 58 HIV+); Overall 36 cases of dementia |

Not specified |

NA |

HIV+: 10.4% |

HIV + patient had a higher frequency of dementia and had dementia at younger age |

| Hospital | |||||||

| HIV-: 3.3% | |||||||

| Ekenze

[21], 2010 |

Nigeria, Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

8440 admissions; 1249 (men 640) with neurological diseases (mean age 45 y.); 44 (men 18) with AIDS dementia complex |

Not specified |

AIDS dementia complex: 3.5% of all neurological admission |

NA |

|

| 2003-2007 | |||||||

| Holguin

[107], 2011 |

Zambia, Hospital |

Case–control |

57 (men 30) HIV- participants (mean age 28 y.); 83 (men 32) HIV + (mean age 34 y.) including 54 naïve of HAART |

IHDS (cut-off ≤ 10) |

HAND = 22% among HIV + naïve of ARV |

NA |

|

| Color Trails Test 1 and | |||||||

| 2008 |

2, Grooved pegboard Test, and Time Gait Test |

||||||

| Joska

[108], 2011 |

South Africa, Hospital |

Case–control |

94 (men 36) HIV- participants (mean age 25.2 y); 96 (men 20) HIV + (mean age 29.8 y) |

IHDS |

NA |

Education associated with IHDS total score |

Validation study of the IHDS |

| 2008 | |||||||

| Obiabo

[109], 2011 |

Nigeria, |

Prospective Cohort study |

69 (men 25) HIV + participants with CD4 < 350 (mean age 36.2 y.); 30 (men 11) HIV- (mean age 36.6 y.) |

CSID and FePsy computerized neuropsychological test battery |

NA |

NA |

HAART improved neuropsychological performances after 12 months of treatment |

| Hospital | |||||||

| Joska

[110], 2011 |

South Africa Hospital |

Cross-sectional |

170 (men 44) HIV + participants (mean age 29.5 y.)never treated; 43 (men 14) with HIV-dementia; 72 (men 19 with MND |

AAN revised criteria |

Mild neurocognitive disorder: 42.4% HIV dementia: 25.4% |

Education, and male gender independent predictors of HIV-dementia |

|

| 2008-2009 | |||||||

| Robertson

[111], 2011 |

Malawi, |

Cross sectional |

133 (men 39) never treated HIV + patients (median age 31 y.) |

Not provided |

MND: 8% |

|

|

| HAD: 0% | |||||||

| Hospital | |||||||

| South Africa, |

167 (men 60) never treated HIV + patients (median age 34 y.) |

Not provided |

MND: 4% |

|

|

||

| HAD: 0% | |||||||

| Hospital | |||||||

| Zimbabwe, Hospital |

80 (men 31) never treated HIV + patients (median age 36 y.) |

Not provided |

MND: 14% |

NA |

860 HIV + HAART naïve patients with CD4 count < 300 cells/mL and KI ≥70% |

||

| HAD: 3% | |||||||

| Robbins

[112], 2011 |

South Africa, |

Cross-sectional |

65 (men 23) HIV + patients on HAART for ≥6 months (mean age 38.5 y) |

IHDS and Xhosa-validated IHDS |

HIV Associated dementia 80% |

Low CD4 counts, alcohol dependency |

|

| Hospital |

2009-2010 |

||||||

| Kwasa

[113], 2012 |

Kenya, |

Cross sectional |

30 (men 17) HIV + patients (mean age 39 y.) |

Neuropsychological test battery MMSE/IHDS (cut-off ≤10) |

HAD 20% |

NA |

|

| Hospital |

6 (men 5)with HAD |

||||||

| Spies

[114], 2012 |

South-Africa, |

Case–control |

35 HIV + without childhood trauma; mean age: 31.5 y |

Neuropsychological test battery |

NA |

NA |

Significant HIV effects for the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) learning and delay trials and the Halstead Category Test (HCT) |

| Hospital |

48 HIV + with childhood trauma; mean age: 31.7 y |

||||||

| 27 HIV- without childhood trauma; mean: 25y | |||||||

| 20 HIV- with childhood trauma; mean age: 27 · 7 y | |||||||

| All participants were women. | |||||||

| Hestad

[115], 2012 |

Zambia, Hospital |

Case–control |

38 HIV + (men 16); mean age: 28.3 y 42 HIV- (men 18); mean age: 28.9 y |

Neuropsychological tests |

NA |

NA |

HIV + individuals performance lower than that of HIV- on verbal fluency, executive function, speed of information processing, verbal episodic memory and motor function |

| Berhe

[116], 2012 |

Ethiopia, |

Cross-sectional |

347 HIV + (men 176) participants; mean age/range: 34.6 y admitted with neurological disorders |

“cognitive and motor abnormalities, CT/MRI showing brain atrophy and other opportunistic infections ruled out” |

HIV encephalopathy: 0.3% |

NA |

|

| Hospital |

Retrospective |

||||||

| 10 had dementia | |||||||

| 2002-2009 | |||||||

| Joska

[117], 2012 |

South Africa, |

Prospective |

166 HIV + participants assessed at baseline, 108 reassessed at one year (82 received HAART) |

Neuropsychological tests |

NA |

Lower level of education |

Improvement on neuropsychological tests for all participants at one year. |

| Average Global deficit score | |||||||

| Hospital | |||||||

| Breuer

[118], 2012 |

South Africa, |

Cross-sectional |

269 HIV + (men 97) participants on HAART for ≥6; months; 34% aged >40 y) |

IHDS (cut-off ≤10.5) |

HAND: 12% |

NA |

|

| Hospital | |||||||

| Hoare

[119], 2012 |

South Africa |

Cross-sectional |

43 stage III HIV + (24 with at least one ϵ4 ApoE allele, men: 8, Age: 29 y and 19 without the ϵ4 ApoE allele, men: 2, Age: 28 y) |

Neuropsychological test battery |

NA |

Performance on Hodgkin Verbal Learning Tool- Revised was poorer in the group with the ϵ4 genotype. |

|

| Participants with the ϵ4 genotype had more white matter injury on MRI. | |||||||

| Hospital | |||||||

| Oshinaike

[120], 2012 |

Nigeria |

Case–control |

208 HIV + (men 71), mean age: 36.8 y |

IHDS (cut off ≤10) |

HAND by MMSE: 2.9% |

Lower CD4 count |

|

| Hospital |

2007-2008 |

||||||

| 121 HIV – (men: 35), mean age:38.0 y |

MMSE (cut off ≤26) |

||||||

| AAN revised criteria (any value below 2SD) | |||||||

| HAND by IHDS: 54.3% | |||||||

| HAND by AAN: 42.3% | |||||||

| Royal [121], 2012 | Nigeria, Hospital | Cross-sectional | 60 (men 23) never treated HIV + participants (mean age 34 y); |

IHDS (cut off ≤10) | 28.8% HIV + individuals scored abnormally |

Low CD4 count, WHO clinical stage of disease | |

| 56 (men 34) HIV- (mean age 29 · 4 y.); 32 had dementia | |||||||

| 16.0% HIV- individuals scored abnormally |

3TC: Lamivudine; AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome; CD4: cluster of differentiation 4; CSID: Community Screening Interview for Dementia; CT: computerized tomography; DSM-III-R: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 3rd edition revised; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th edition; dT4: Didanosine; FePsy: The Ion Psyche Program; HAART: Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Treatment; HAD: HIV Associated Dementia; HAND: HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders; HDS: HIV Dementia Scale; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; ICD-III-R: International Classification of Disease; IHDS: International HIV Dementia Scale; MSK: Memorial Sloan Kettering; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; MND: Mild Neurocognitive Disorder; NA: Not available; NVP: Nevirapine; WHO: World Health Organization; y, years; ZDV: Zidovudine.

The diagnostic tools used to identify HIV-related dementia were variable, making comparison between studies less reliable. However, the International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) [89,95,97,105,107-110,112,113,120,121] and the Sloan Memorial Kettering scale [86,89,90,98] were frequently used. Studies that used the IHDS reported a prevalence ranging from 21.1 to 80%. The mean/median age of participants ranged from 31 to 40 years for those with HIV-related dementia, and men represented 25% to 56% of this group. In the nine studies that investigated etiological factors, the identified determinants of HIV-related dementia were: low level of CD4 count (four studies), low level of education, and advanced age (three studies), comorbid psychiatric conditions (two studies each), advance clinical stage (two studies), male sex, HIV-subtype and duration of disease (one study each). The most commonly reported risk factors of HIV associated dementia were the level of CD4 count [89,97,112,120,121] and the clinical stage of disease [97,121].

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and cerebellar degeneration

Fifteen studies (12 retrospective, 2 cross-sectional and 1 case-series) (Table 4) including 13 hospital and two community-based studies on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have been conducted in 9 SSA countries including Nigeria (four studies), Senegal (three studies), Ethiopia (2 studies), Zimbabwe, Kenya, South Africa, Sudan, Cameroon and Ivory coast (one study each). The number of participants with ALS ranged from two to 73. Two community-based studies provided a prevalence of 15/100,000 and 5/100,000 respectively in Nigeria [19] and in Ethiopia [122]. Five hospital-based studies provided prevalence figures: between 0.2 and 8.0/1000 of all neurologic consultation/admission [16,21,122-126]. The method of ascertainment of ALS was variable across studies, but electromyography was done in four of the fifteen studies included [125-129]. The proportion of men among those with ALS was 57.6 to 100%. The age of those with ALS ranged from 12 to 84 years. When provided, the age at the clinical onset of ALS ranged from 12 to 71 years and the time to diagnosis from 3 months to more than 15 years. In general, risk factors for ALS were not investigated across studies.

Table 4.

Overview of studies on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis risk factors in sub-Sahara Africa

| Author, year of publication | Country/setting | Design/year | Population characteristics | Diagnostic criteria/tools | Prevalence | Risk factors | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall

[130],1972 |

Zimbabwe |

Retrospective |

13 (men 10) consecutive patients; age 24–55 y. |

Clinical (no ENMG) |

NA |

NA |

6 participants had sensory changes |

| Hospital-based |

1967-1971 |

||||||

| Osuntokun

[126], 1974 |

Nigeria |

Retrospective |

92 patients with MND ALS 73; PMA 10, SMA 9 |

ENMG/Muscle biopsy/ |

21/100,000 |

NA |

Mean age at onset: 39 y |

| Mean duration of disease exceeded 15 y in 8% of participants | |||||||

| Hospital-based |

1958 -1973 |

||||||

| 4 patients with ALS had poliomyelitis in childhood. | |||||||

| Osuntokun

[19], 1987 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

18954 participants (men 9282); 58% <20 y and 11% > 50 y |

Screening questionnaire developed by the authors |

MND: 15/100,000 |

NA |

|

| Community-based |

1985 |

||||||

| Cosnett

[125], 1989 |

South Africa Hospital-based |

Retrospective Cases collected during 9.5 y. |

59 blacks (mean age 47.4 y.); 16 whites and 2 coloured (mean age 54 y.) 9 Indians (mean age 54 y) |

Clinical and ENMG in 45% |

Blacks/white & coloured/Indians (per 100,000) 0.88/2 · 7/1.4 |

NA |

Mean age of onset: 47 y (blacks) and 54 y (in whites and Indians) |

| 29% of participants not followed up. | |||||||

| Ekenze

[21], 2010 |

Nigeria |

Retrospective |

8440 admissions; 1249 (men 640) with neurological diseases, mean age 45 y.; 10 (men 4) with ALS |

Not specified |

800/100,000 |

NA |

|

| Hospital-based |

2003-2007 |

||||||

| Abdulla

[127], 1997 |

Sudan |

Retrospective: |

28 (men 17) patients with MND; 19 (men 14) with ALS |

Clinical and ENMG |

NA |

Family history of MND in 14% |

Mean age of onset: 40 y |

| Hospital-based |

1993-1995 |

||||||

| Kengne

[16], 2006 |

Cameroon |

Retrospective |

4041 neurologic consultations; 145 with neurodegenerative diseases 10 (men 8) with ALS; mean age 50.9 y. |

Not provided |

12% of all neurodegeneration 250/100,000 of all neurologic consultation |

|

4 selected degenerative brain diseases: Dementia, PD, ALS and chorea |

| Hospital-based |

1993-2001 |

||||||

| Imam

[131], 2004 |

Nigeria |

Retrospective |

16 (men 15) participants; age 16-60 y. |

El Escorial diagnostic criteria for ALS, no ENMG |

NA |

NA |

|

| Hospital-based |

1980-99 |

||||||

| Adam

[129], 1992 |

Kenya |

Retrospective |

47(men 35) participants with MND; |

Clinical (ENMG in 1/3 of participants) |

NA |

NA |

Duration of disease: 5 m to 4 y. |

| Hospital-based |

1978-88 |

Age 13-80 y |

|||||

| 18 had ALS | |||||||

| Tekle-Haimanot

[122], 1990 |

Ethiopia |

Cross-sectional |

60820 participants (men 29412), 59% aged < 20 y |

Screening questionnaire and neurological exam |

5/100,000 |

NA |

A population survey of neurological diseases |

| Community-based |

1986-88 |

3 (2 men) had MND |

|||||

| Harries

[132], 1955 |

Ethiopia |

Case series |

2(all males) participants |

Clinical (no ENMG) |

NA |

NA |

|

| Age 26 and 30 y | |||||||

| Hospital-based |

1954 |

||||||

| Jacquin-cotton

[123], 1970 |

Senegal |

Retrospective |

6100 participants with neurological disorders |

Clinical (No ENMG) |

290/100,000 |

|

A study of patients with paraplegia in a neurological unit |

| Hospital-based |

1960-1969 |

18 (16 men) participants with ALS, age 25-70 y |

|||||

| Piquemal

[124], 1982 |

Ivory coast |

Retrospective |

4000 participants with neurological disorders |

Clinical (no ENMG) |

750/100,000 |

NA |

Duration of disease: 3 m to 5 y. |

| Hospital-based |

1971-80 |

30 (men 22) participants had ALS, 50% aged <40 y |

|||||

| Collomb

[133], 1968 |

Senegal |

Retrospective |

18 (17 men) participants with ALS, age 25-70 y |

Clinical (no ENMG) |

NA |

NA |

Duration of disease: 4 m to 13 y |

| Hospital-based |

1960-68 |

||||||

| Sene

[128], 2004 |

Senegal Hospital- |

Retrospective |

33 (19 men) participants with ALS; |

El Escorial |

|

|

Definite ALS: 57%, |

| Probable: 30%, Possible ALS: 9% | |||||||

| Suspect ALS: 3% age at onset 14–67 y. | |||||||

| (ENMG in half of the patients) |

|||||||

| based | 1999-2000 | Duration of disease: 6 m to 5 y. |

ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ENMG: Electroneuromyography; MND: Motor Neuron Disease; NA: Not available; PMA: Progressive muscular atrophy; SMA: Spinal Muscular Atrophy; y: years; m: months.

One retrospective study in Nigeria reported on two cases (a 32 year old male and a 42 year old female) of cerebellar degeneration among 2 · 1 million admissions over a period of 25 year [14]. One study in Rwanda reported on a family of 33 members, with 15 (including eight men, age at onset 12–49 years) having type 2 spino-cerebellar ataxia [134]. A study in Mauritania reported on 12 cases of cerebellar degeneration-based on clinical criteria, including 9 familial cases (including 7 men, aged 3 to 29 years) and 3 apparently sporadic cases (all men, aged 8 to 50 years) [135]. Another clinic-based study of paraplegia in Senegal reported on 7 cases of spino-cerebellar degeneration among 6100 neurological admissions [123].

Huntington disease