Abstract

Background

With the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, immunosuppressive drugs, and glucocorticoids, multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDR-AB) has become a major nosocomial pathogen species. The recent renaissance of bacteriophage therapy may provide new treatment strategies for combatting drug-resistant bacterial infections. In this study, we isolated a lytic bacteriophage vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 has a short latent period and a small burst size, which clear its host’s suspension quickly, was selected for characterization and a complete genomic comparative study.

Results

The isolated bacteriophage vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 has an icosahedral head and displays morphology resembling Myoviridae family. Gel separation assays showed that the phage particle contains at least nine protein bands with molecular weights ranging 15–100 kDa. vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 could adsorb its host cells in 9 min with an adsorption rate more than 99% and showed a short latent period (20 min) and a small burst size (62 pfu/cell). It could form clear plaques in the double-layer assay and clear its host’s suspension in just 4 hours. Whole genome of vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 was sequenced and annotated and the results showed that its genome is a double-stranded DNA molecule consisting of 43,665 nucleotides. The genome has a G + C content of 37.5% and 82 putative coding sequences (CDSs). We compared the characteristics and complete genome sequence of all known Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophages. There are only three that have been sequenced Acinetobacter baumannii phages AB1, AP22, and phiAC-1, which have a relatively high similarity and own a coverage of 65%, 50%, 8% respectively when compared with our phage vB_AbaM-IME-AB2. A nucleotide alignment of the four Acinetobacter baumannii phages showed that some CDSs are similar, with no significant rearrangements observed. Yet some sections of these strains of phage are nonhomologous.

Conclusion

vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 was a novel and unique A. baumannii bacteriophage. These findings suggest a common ancestry and microbial diversity and evolution. A clear understanding of its characteristics and genes is conducive to the treatment of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii in the future.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, Bacteriophage, Characteristics, Genome

Background

Acinetobacter baumanni is a non-fermentative, aerobic, gram-negative bacillus, and is an opportunistic pathogen with global distribution. It is frequently found in elderly patients and cancer patients with compromised immune function, especially in intensive care units. With the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, immunosuppressive drugs, and glucocorticoids, A. baumannii (AB) has become a major nosocomial pathogen species [1]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), and pan drug-resistant (PDR) A. baumannii strains are increasingly prevalent [2]. MDR-AB refers to A. baumannii strains that are resistant to at least three of the following five types of antimicrobial agents: cephalosporins, carbapenems, β-lactamase inhibitors (including piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoperazone/sulbactam, ampicillin/sulbactam), fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides [2-4].

Bacteriophage therapy is a potential alternative treatment for multidrug-resistant bacterial infections [5]. A bacteriophage is a bacterial virus that can lyse and kill the host cell. Phage-related studies have gone through three stages. Félix d’Herelle discovered bacteriophage for the treatment of bacterial infections in 1917 [6]. After the emergence of antibiotics in the 1940s, phages were seldom used for therapeutic purposes, and mainly functioned as molecular and genetic research tools. With the recent emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria, however, there has been renewed interest in methods of phage therapy [7]. In this study we isolated a lytic bacteriophage IME-AB2, and compared biological characteristics and genomic sequence with other Acinetobacter baumannii phages. The genomes of A. baumannii phages IME-AB2, A. baumannii AB1, A. baumannii AP22, and A. baumannii phiAC-1 were compared thoroughly in this study. To our knowledge this is the first report of comparison of the characteristics and complete genome sequence of Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophages. A clear understanding of its genes is conducive to the treatment of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii in the future.

Results

Isolation of a lytic bacteriophage against multidrug-resistant A. baumannii

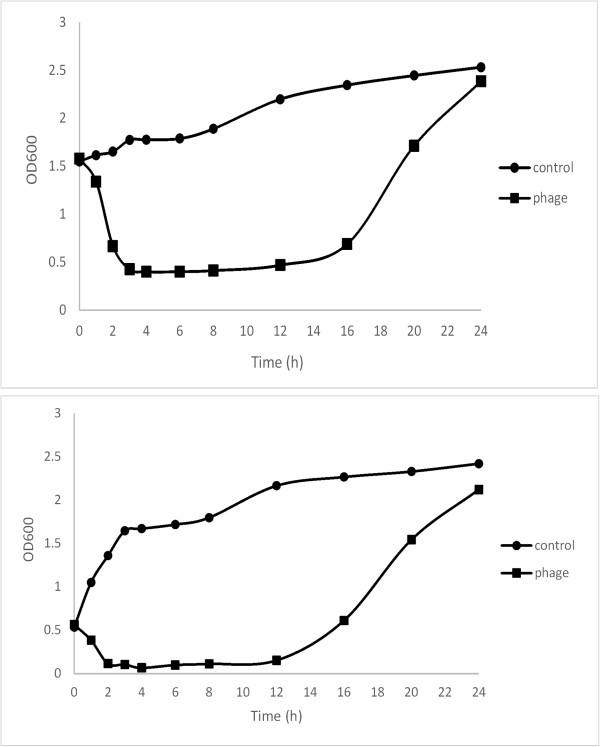

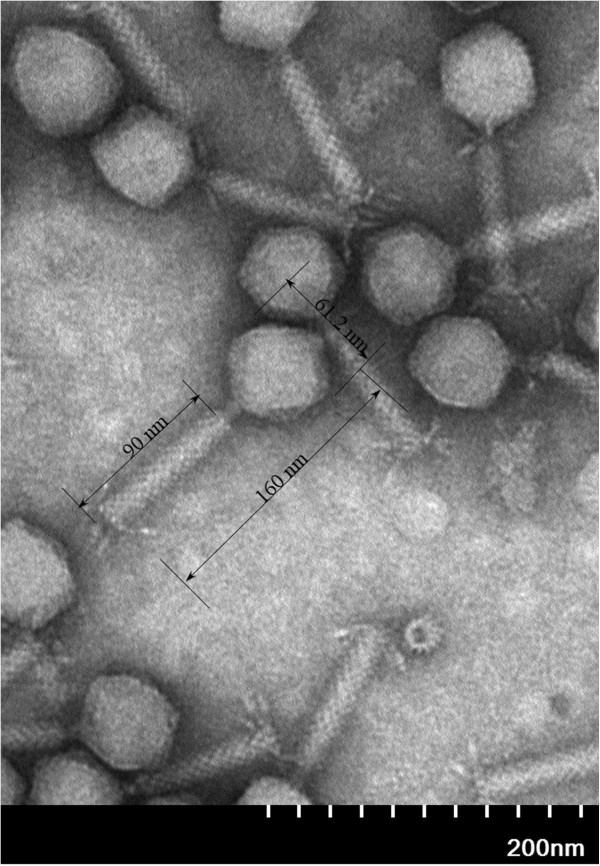

A. baumannii strain MDR-AB2, isolated from a sputum sample of a patient with pneumonia at PLA Hospital 307, was resistant to multiple antibiotics (Table 1). The bacteria was used to screen bacteriophages in sewage samples from PLA Hospital 307. The isolated phage was designated as vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 following the recommendation by International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses in phage nomenclature [8]. The pahge IME-AB2 could form clear plaques in the double-layer assay and clear its host’s suspension in just 4 hours (Figure 1), indicating that it is a lytic phage. In order to check the development of resistance, we had extended the period of the experiment to 24 h. The result indicated that the bacterial suspension became turbid finally. The final suspension was plated on solid LB culture and then some single bacterial clones were picked to be used for 16 s rDNA sequencing. The sequences of 16 s rDNA proved that the final suspension was A. baumannii that developed resistance to IME-AB2. The phage particles were concentrated with PEG6000 and then purified with a cesium chloride gradients density to a titer of 1 × 1011 pfu/ml. Observation under an electron microscope showed that the phage IME-AB2 consisted of an icosahedral head and a contractile tail. The total length of the phage from the top of the head to the bottom of the tail was about 160 nm, with the head measuring approximately 61.2 nm, and the tail about 90 nm. This morphology suggested that phage IME-AB2 should be classified as a member of the Myoviridae family (Figure. 2). Among the 22 clinical strains of A. baumannii, only three strains of A. baumannii (MDR-AB1139, MDR-AB2 and MDR-AB11) could be lysed by the phage IME-AB2.

Table 1.

Antibiotic resistance profile of A. baumannii strain MDR-AB2

| Antibiotics | MIC (μg/ml) | Sensitivity | Antibiotics | MIC (μg/ml) | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin |

≥ 32 |

Resistant |

nitrofurantoin |

≥ 512 |

Resistant |

| Ciprofloxacin |

≥ 4 |

Resistant |

ampicillin/sulbactam |

≥ 32 |

Resistant |

| Gentamicin |

≥ 16 |

Resistant |

aztreonam |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Imipenem |

≥ 16 |

Resistant |

cefepime |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Meropenem |

≥ 16 |

Resistant |

cefotetan |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Piperacillin |

≥ 128 |

Resistant |

ceftazidime |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam |

≥ 128 |

Resistant |

ceftriaxone |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Tobramycin |

≥ 16 |

Resistant |

cefuroxime axetil |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Cotrimoxazole |

≥ 320 |

Resistant |

cefuroxime sodium |

≥ 64 |

Resistant |

| Levofloxacin | ≥ 8 | Resistant | cefoperazone/sulbactam | ≥ 64 | Resistant |

Figure 1.

The MDR-AB2 suspension at the different optical density (OD600nm) reached to 0.4 from 1.6 and reached to 0.08 from 0.6 respectively after added 200ul IME-AB2 (1 × 1011 pfu/ml) to the 10 ml MDR-AB2 suspension. It clear its host’s suspension in just 4 hours. The control shows increasing OD600nm. The MDR-AB2 suspension added with IME-AB2 finally became turbid in 24 hours.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy of phage IME-AB2. The bidirectional arrows indicated the length of intact phage, phage tail and head. The bar represents a length of 200 nm.

Growth and lytic characteristics of IME-AB2

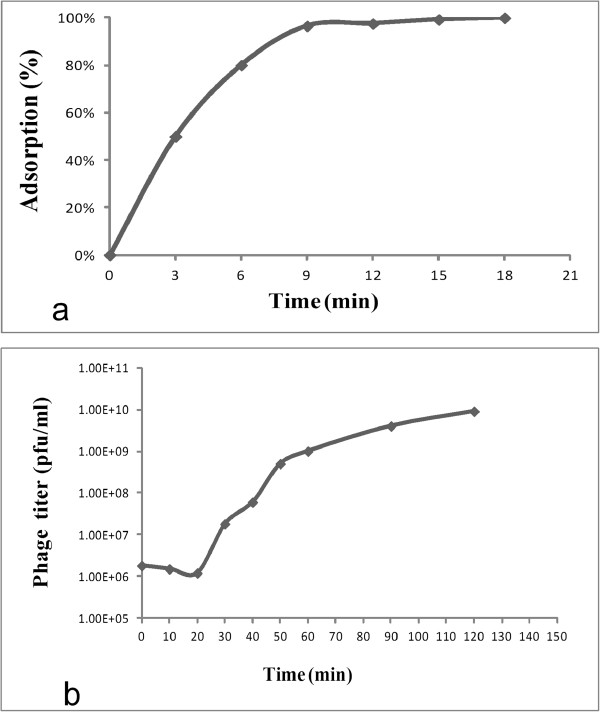

To determine the optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI) of IME-AB2, the phage and its host cells were mixed at various ratios, and incubated for 3.5 h at 37°C. The results indicated that a MOI of 20 gave the highest production of phage progeny (3.5 × 1011 pfu/ml). To examine the host adsorption ability of phage IME-AB2, host bacteria were infected with IME-AB2 at a MOI of 0.1 and incubated at 37°C. Aliquots were taken at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 min post-infection and assayed for the absorbed phage by titration using the double-layer method. The percentages of phage absorption at different time points were plotted (Figure 3a). The results showed that phage IME-AB2 had an adsorption rate of 50% within 3 min, 80% within 6 min and 99% within 9 min.

Figure 3.

Biological characteristics of phage IME-AB2. a. Host adsorption ability of phage IME-AB2. b. One-step growth curve of phage IME-AB2.

For one-step growth curve analysis, MDR-AB2 cells (OD600 = 0.3) were infected with phage IME-AB2 at a MOI of 0.1. The bacteriophage was allowed to adsorb for 15 min at 37°C [9]. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 s to remove unadsorbed phage particles, and the resultant pellet was re-suspended in 5 ml of LB medium. Samples were incubated at 37°C and collected every 10 min during 0–60 min, as well as at 90 and 120 min [10]. As shown in Figure 3b, the latent period of phage IME-AB2 lasted for 20 min, the burst period reached a peak at 30 min, and the phage multiplication reached the final plateau phase at 50 min. The burst size of phage IME-AB2 was determined to be 62 pfu/cell (burst size = the total number of phages liberated at the end of one cycle of growth /the number of infected bacteria) [11].

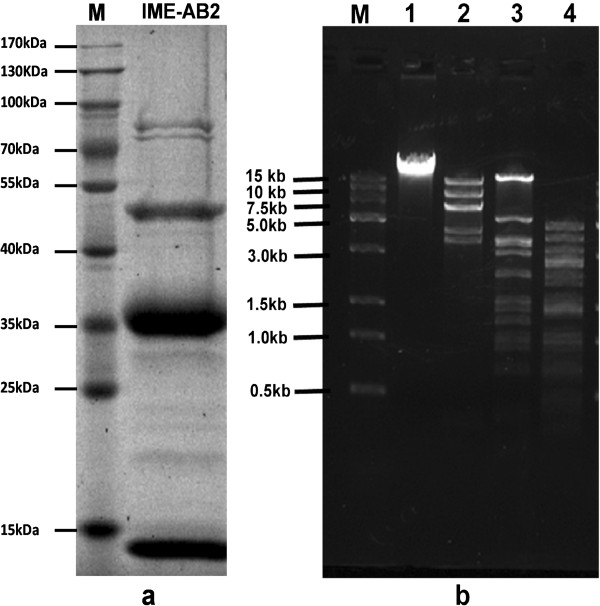

Analysis of the phage proteins and genome

Purified phage particles were denatured in loading buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 2% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-polyacrylamide, 0.1%Bromophenol blue, 10% Glycerol and 1% β-Mercaptoethanol) and heated in a boiling water bath for 5 min, followed by separation of the proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The results indicated that the structural proteins of phage IME-AB2 showed a pattern of nine protein bands in 10% SDS-PAGE gel, with molecular masses ranging from 15–100 kDa (Figure 4a). The most abundant protein band in the gel above 35 kDa was analyzed with liquid sampling Mass Spectrometry (LS-MS) and proved to be the phage putative capsid protein.

Figure 4.

Protein and genomic DNA analysis of phage IME-AB2. a. SDS-PAGE gel (10%) of whole protein from phage IME-AB2. Molecular weights of protein marker was indicated by lines. b. Endonuclease digestion analysis of phage IME-AB2 genomic DNA. Phage IME-AB2 genomic DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme NdeI, HincII and HindIII. The digested DNA fragments were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. M, DNA molecular weight marker; Lanes 1, undigested phage IME-AB2 genomic DNA; lane 2, 3, 4, genomic DNA digested with NdeI , HincII and HindIII, respectively.

The genome analysis indicated that phage IME-AB2 has a double-stranded DNA genome, approximately 40 kb in size. The genome of phage IME-AB2 could be digested with endonuclease NdeI, HincII and HindIII (Figure 4b). It was found that endonuclease enzymes, HindIII and HincII, have the 35 and 16 cutting sites on the genome of phage IME-AB2 respectively by Vector NTI [12]. Compared to other A. baumannii complete genome , the two endonucleases also have most restriction enzyme cutting sites on them.

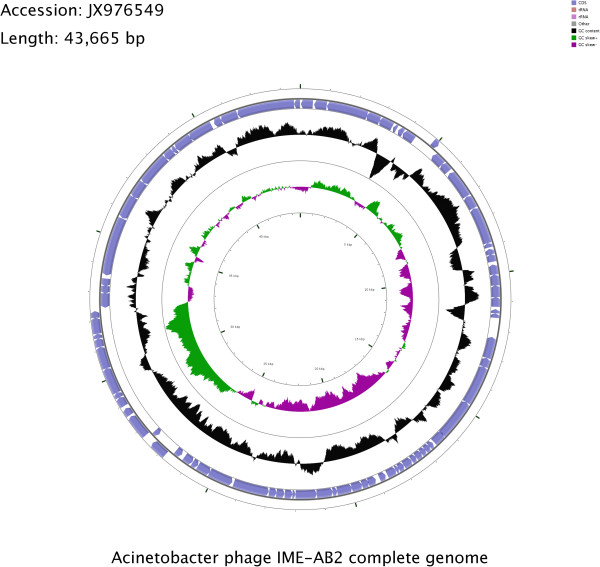

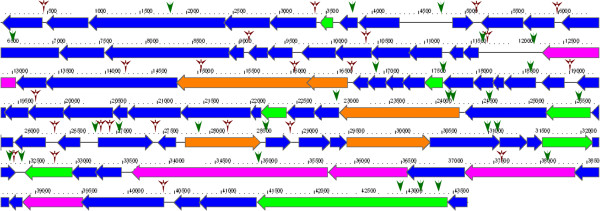

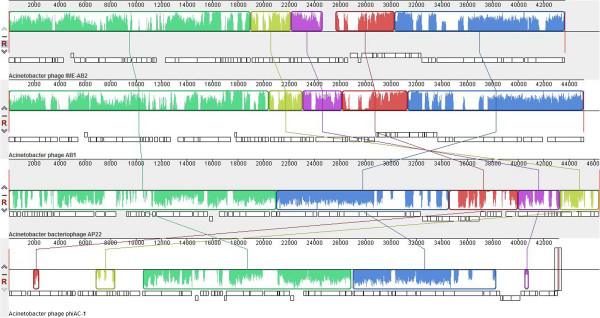

High-throughput sequencing of the phage genomic DNA generated 311,503 valid reads with which the complete sequence of the genome was assembled using both Velvet and CLC Genomic Workbench, with an average coverage of 785 × [13]. The complete genome of phage IME-AB2 consists of 43,665 bp, with an average GC content of 37.5% (Figure 5). Annotation results showed that the genome encodes 82 coding sequences (CDSs) (GenBank Assession number: JX976549). The classification of the 82 CDSs is shown in Table 2 and Figure 6. The complete genome of IME-AB2 is organized into three functional units which encoding structural proteins, metabolic proteins and packaging-associated proteins respectively. No tRNA was found in the genome of IME-AB2, and no significant proteins considered to be markers of temperate bacteriophages were identified. Running blastn showed that the isolated IME-AB2 has a high similarity to Acinetobacter phage AB1 (Genbank Accession Number: HM368260.1), Acinetobacter phage AP22 (Genbank Accession Number: HE806280.1) and Acinetobacter phage phiAC-1 (GenBank accession number: JX560521), which were isolated in China, Russia and Korea respectively. The phage AB1, AP22 or phiAC-1 has a genome of about 45 kb and owns a coverage of 65%, 50%, 8% respectively when compared with the isolated phage IME-AB2. Genomic annotation found that IME-AB2 encodes 82 CDSs, AB1 85 CDSs, AP22 89 CDSs, phiAC-1 82 CDSs. The 82 CDSs from IME-AB2 shared 63 homologues with AB1, 60 homologues with AP22 and 36 homologues with phiAC-1 respectively (Table 3). Totally, 22 of the 82 CDSs encoded by IME-AB2 were identified to be putatively functional. Genomic analysis revealed that the bacteriophage IME-AB2 was most closely related to AB1. A nucleotide alignment of the four Acinetobacter baumannii phages showed that some functional regions are highly homologous, with no significant rearrangements observed (Table 3 and Figure 7). It revealed a stable area. Stability is suggested from the high level of nucleotide identity, lack of inversions and other major rearrangements, and the stabilizing selection inferred for virtually all genes harboring synonymous and non-synonymous mutations [14]. Functional related genes are sequential, yet there are a lot of breakpoint modules obviously and some sections of these strains of phages are nonhomologous (Table 3 and Figure 7). It illustrated that these structural genes had occurred in the extensive structural rearrangements during evolution. Bacteriophages are the most diverse and abundant biological entities in nature environment. Most of them can hardly to be found homologous to another bacteriophage, which means evolutionary success obtained by bacteriophages. Furthermore, the diversity is such that even genes with required functions cannot always be recognized. During bacteriophage evolution,the elimination or recombination of genes result in the diversity and meanwhile confer a selective advantage to survive and infect so that phages can better adapt to host bacteria.

Figure 5.

Circular map of the IME-AB2 genome prepared using CGView. The outer ring denotes the IME-AB2 genome and CDSs. The inner rings show G + C content and G + C skew, where peaks represent the positive (outward) and negative (inward) deviation from the mean G + C content and G + C skew, respectively.

Table 2.

Functional classification of the 82 CDSs in the IME-AB2 genome

| Category | CDSs and putative functions |

|---|---|

| Structural proteins |

CDS.12 putative capsid protein. |

| CDS.13 putative structural protein. | |

| CDS.24 putative phage head protein. | |

| CDS.71 putative tail fiber. | |

| CDS.72 similar to the N-terminal region of tail fiber protein. | |

| CDS.74 putative baseplate J-like protein. | |

| CDS.77 putative phage baseplate assembly protein. | |

| Metabolic proteins |

CDS.06 putative cobalt transport protein. |

| CDS.08 putative RNA polymerase. | |

| CDS.33 putative binding HTH domain or homeodomain-like. | |

| CDS.47 putative bacteriophage-associated immunity protein. | |

| CDS.52 putative HNH endonuclease domain protein. | |

| CDS.66 putative nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase. | |

| CDS.68 putative lysozyme family protein. | |

| CDS.81 putative lysozyme protein. | |

| Replication/packaging-associated proteins |

CDS.26 putative phage head portal protein. |

| CDS.27 putative phage terminase, large subunit. | |

| CDS.28 putative phage terminase,small subunit. | |

| CDS.50 putative replicative DNA helicase. | |

| CDS.51 putative primosomal protein. | |

| CDS.58 putative transcriptional regulator. | |

| CDS.62 putative recombinational DNA repair protein. | |

| Other hypothetical proteins |

CDS.1,2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,29,30,31, |

| 32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,51,53,54,55,56,57,59,60, | |

| 61,63,64,65,67,69,70,73,75,76,78,79,80,82. |

Figure 6.

Genome map of phage IME-AB2. Arrows indicate putative CDSs, along with their orientations. Functionally assigned genes are differently colored (purple, structural gene; green, metabolic gene; orange, replication/packaging-associated gene; blue, other gene). Promoters are illustrated as green arrowheads, while terminators are displayed as red arrowheads.

Table 3.

Comparative genomic analysis of A. baumannii phage IME-AB2, A. baumannii phage AB1, A. baumanni i phage AP22, and A3 baumannii phage phiAC-1

| IME-AB2 (82CDSs) | AB1 (85CDSs) | Score (bits) | E-value | phiAC-1 (82CDSs) | Score (bits) | E-value | AP22 (89CDSs) | Score (bits) | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CDS.01 |

gp01 |

134 |

9e-35 |

0055 |

190 |

1e-51 |

gp42 |

290 |

1e-81 |

|

CDS.02 |

gp02 |

192 |

4e-52 |

0054 |

205 |

3e-56 |

gp41 |

130 |

9e-34 |

|

CDS.03 |

gp03 |

895 |

0.0 |

0053 |

645 |

0.0 |

gp40 |

813 |

0.0 |

|

CDS.04 |

gp04 |

334 |

5e-95 |

0052 |

207 |

1e-56 |

gp39 |

325 |

4e-92 |

|

CDS.05 |

gp06 |

345 |

2e-98 |

0051 |

220 |

1e-60 |

gp38 |

329 |

2e-93 |

|

CDS.06 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.07 |

gp08 |

57 |

8e-12 |

0050 |

45 |

3e-08 |

gp36 |

52 |

3e-10 |

|

CDS.08 |

gp09 |

270 |

7e-76 |

0049 |

99 |

3e-24 |

gp35 |

262 |

3e-73 |

|

CDS.09 |

gp10 |

150 |

4e-40 |

0048 |

128 |

2e-33 |

gp34 |

150 |

4e-40 |

|

CDS.10 |

gp12 |

298 |

3e-84 |

0047 |

221 |

5e-61 |

gp32 |

299 |

2e-84 |

|

CDS.11 |

gp13 |

74 |

1e-16 |

0046 |

75 |

6e-17 |

gp31 |

65 |

4e-14 |

|

CDS.12 |

gp15 |

207 |

2e-56 |

0043 |

208 |

1e-56 |

gp30 |

250 |

2e-69 |

|

CDS.13 |

gp16 |

120 |

2e-30 |

0042 |

124 |

1e-31 |

gp29 |

99 |

6e-24 |

|

CDS.14 |

gp17 |

523 |

e-151 |

0041 |

402 |

e-115 |

gp28 |

546 |

e-158 |

|

CDS.15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.16 |

gp19 |

144 |

4e-38 |

0038 |

31 |

5e-04 |

gp27 |

36 |

1e-05 |

|

CDS.17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.21 |

gp23 |

55 |

4e-11 |

|

|

|

gp22 |

71 |

9e-16 |

|

CDS.22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.23 |

|

|

|

0022 |

40 |

1e-06 |

gp21 |

39 |

2e-06 |

|

CDS.24 |

gp27 |

414 |

e-119 |

0031 |

325 |

6e-92 |

gp18 |

404 |

e-116 |

|

CDS.25 |

gp28 |

204 |

4e-56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.26 |

gp30 |

831 |

0.0 |

0029 |

658 |

0.0 |

gp17 |

804 |

0.0 |

|

CDS.27 |

gp31 |

627 |

0.0 |

0028 |

64 |

7e-13 |

gp16 |

60 |

8e-12 |

|

CDS.28 |

gp33 |

305 |

2e-86 |

0027 |

22 |

0.82 |

gp15 |

20 |

2.7 |

|

CDS.29 |

gp34 |

31 |

6e-04 |

0038 |

35 |

3e-05 |

gp27 |

32 |

3e-04 |

|

CDS.30 |

gp34 |

35 |

2e-05 |

|

|

|

gp14 |

30 |

6e-04 |

|

CDS.31 |

gp34 |

31 |

6e-04 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.32 |

gp35 |

149 |

1e-39 |

|

|

|

gp12 |

83 |

1e-19 |

|

CDS.33 |

gp36 |

112 |

1e-28 |

|

|

|

gp10 |

114 |

4e-29 |

|

CDS.34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.35 |

gp39 |

133 |

6e-35 |

|

|

|

gp05 |

137 |

4e-36 |

|

CDS.36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.38 |

gp40 |

147 |

3e-39 |

0010 |

50 |

1e-09 |

gp02 |

124 |

3e-32 |

|

CDS.39 |

gp42 |

186 |

1e-50 |

0021 |

152 |

1e-40 |

|

|

|

|

CDS.40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

gp88 |

139 |

8e-37 |

|

CDS.41 |

gp43 |

92 |

3e-22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.42 |

gp44 |

152 |

5e-40 |

|

|

|

gp87 |

71 |

1e-15 |

|

CDS.43 |

gp45 |

97 |

7e-24 |

|

|

|

gp86 |

95 |

2e-23 |

|

CDS.44 |

gp46 |

379 |

e-108 |

|

|

|

gp85 |

390 |

e-112 |

|

CDS.45 |

gp47 |

388 |

e-111 |

|

|

|

gp84 |

186 |

6e-50 |

|

CDS.46 |

gp48 |

68 |

5e-15 |

|

|

|

gp83 |

70 |

9e-16 |

|

CDS.47 |

gp49 |

72 |

2e-16 |

0019 |

42 |

2e-07 |

gp82 |

71 |

4e-16 |

|

CDS.48 |

gp50 |

192 |

1e-52 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.49 |

gp51 |

126 |

8e-33 |

0009 |

42 |

2e-07 |

gp79 |

159 |

9e-43 |

|

CDS.50 |

gp52 |

863 |

0.0 |

|

|

|

gp77 |

619 |

e-180 |

|

CDS.51 |

gp53 |

204 |

2e-55 |

|

|

|

gp76 |

157 |

2e-41 |

|

CDS.52 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.53 |

gp54 |

130 |

5e-34 |

|

|

|

gp75 |

133 |

7e-35 |

|

CDS.54 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.55 |

gp57 |

150 |

5e-40 |

|

|

|

gp72 |

128 |

3e-33 |

|

CDS.56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.57 |

gp60 |

72 |

3e-16 |

|

|

|

gp69 |

74 |

8e-17 |

|

CDS.58 |

gp62 |

216 |

6e-59 |

|

|

|

gp68 |

295 |

4e-83 |

|

CDS.59 |

gp63 |

153 |

6e-41 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.60 |

gp64 |

187 |

9e-51 |

|

|

|

gp66 |

192 |

2e-52 |

|

CDS.61 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

gp65 |

123 |

8e-32 |

|

CDS.62 |

gp66 |

594 |

e-173 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.63 |

gp67 |

489 |

e-141 |

|

|

|

gp63 |

38 |

2e-05 |

|

CDS.64 |

gp68 |

189 |

2e-51 |

|

|

|

gp62 |

187 |

5e-51 |

|

CDS.65 |

gp70 |

59 |

2e-12 |

|

|

|

gp61 |

60 |

8e-13 |

|

CDS.66 |

gp71 |

125 |

5e-32 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.67 |

gp72 |

143 |

5e-38 |

0079 |

80 |

1e-18 |

gp59 |

128 |

2e-33 |

|

CDS.68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDS.69 |

gp74 |

171 |

3.00E-46 |

|

|

|

gp56 |

174 |

4e-47 |

|

CDS.70 |

gp75 |

175 |

2e-47 |

|

|

|

gp55 |

174 |

3e-47 |

|

CDS.71 |

gp76 |

221 |

4e-60 |

0069 |

189 |

1e-50 |

gp54 |

252 |

1e-69 |

|

CDS.72 |

gp77 |

304 |

1e-85 |

0068 |

216 |

3e-59 |

gp53 |

313 |

2e-88 |

|

CDS.73 |

gp78 |

418 |

e-120 |

0067 |

332 |

3e-94 |

gp52 |

421 |

e-121 |

|

CDS.74 |

gp79 |

790 |

0.0 |

0066 |

585 |

e-170 |

gp51 |

796 |

0.0 |

|

CDS.75 |

gp80 |

213 |

1e-58 |

0065 |

164 |

4e-44 |

gp50 |

214 |

6e-59 |

|

CDS.76 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

gp49 |

59 |

2e-12 |

|

CDS.77 |

gp81 |

429 |

e-123 |

0064 |

200 |

2e-54 |

gp48 |

430 |

e-123 |

|

CDS.78 |

gp82 |

575 |

e-167 |

0063 |

437 |

e-125 |

gp47 |

573 |

e-166 |

|

CDS.79 |

|

|

|

0061 |

124 |

4e-32 |

gp46 |

170 |

5e-46 |

|

CDS.80 |

gp83 |

352 |

e-100 |

0060 |

277 |

1e-77 |

gp45 |

351 |

e-100 |

|

CDS.81 |

gp84 |

710 |

0.0 |

0057 |

368 |

e-104 |

gp44 |

715 |

0.0 |

| CDS.82 | gp85 | 77 | 6e-18 | 0056 | 61 | 6e-13 | gp43 | 145 | 2e-38 |

IME-AB2 is the reference for alignments and comparisons to the three other strains (AB1,phiAC-1 and AP22).

Figure 7.

Multiple genome alignment performed using Mauve software (http://asap.ahabs.wisc.edu/mauve/) and the chromosomes of A. baumannii IME-AB2, A. baumannii AB1, A. baumannii AP22, and A. baumannii phiAC-1. IME-AB2 is the reference for alignments and comparisons to the three other strains. Boxes with identical colors represent local colinear blocks (LCB), indicating homologous DNA regions shared by two or more chromosomes without sequence rearrangements. LCBs indicated below the horizontal black line represent reverse complements of the reference LCB.

Structural proteins

Seven CDSs encoding structural proteins were identified in the phage IME-AB2. The putative capsid protein (CDS.12) is similar to that of phage AB1 (gp15), phage AP22 (gp30), phage phiAC-1 (0043). Phage AB1 (gp27), phage AP22 (gp18), phage phiAC-1 (0031) also share homology to the putative phage head protein encoded by IME-AB2 CDS.24. CDS.71 and CDS.72 of phage IME-AB2 are identified to be associated with tail fiber protein. CDS.74 and CDS.77 of phage IME-AB2 are predicted to encode proteins responsible for baseplate. These two related proteins can be found similar area in the other three phages. The results also demonstrate the phage tail related proteins generally cluster together (Table 3).

Metabolic proteins

A unique feature of the IME-AB2 genome is that it encodes cobalt transport protein (CDS.6). Notably, cobalt is a cofactor and is required by enzymes from bacteria [15]. It is possible that these metabolic enzymes benefit phage by enhancing the metabolism of the infected bacterial cell, which could in turn increase phage proliferation. No similar cobalt proteins were found in the other three phages sharing homology with IME-AB2. CDS.8 encodes a putative RNA polymerase protein. It is necessary for constructing RNA chains using DNA genes as templates, a process called transcription. Transcription of most double-stranded DNA bacteriophages rely on their host bacteria [16]. The putative CDS.33 of IME-AB2 is predicted to encode HTH domains which have been recruited to a wide range of functions beyond transcription regulation, such as DNA repairing and replication, RNA metabolism and protein-protein interactions in diverse signaling contexts. Beyond their basic role in mediating macromolecular interactions, the HTH domains have also been incorporated into the catalytic domains of diverse enzymes [17]. In functional terms, the HNH endonuclease domain (CDS.52) is found in CRISPR-related proteins. CRISPR functions as a prokaryotic immune system, in that it confers resistance to exogenous genetic elements [18]. CDS.47 is predicted to be a putative bacteriophage-associated immunity protein, which was considered to be responsible for phage superinfection immunity [19]. CDS.68 and CDS.81 are putative lysozyme family protein. Unlike, CDS.0057, 0058, 0059 encoded by phiAC-1, which are putative lysozyme-like domain protein and adjacent to each other, the two lysozyme-like proteins from IME-AB2 are not clustered.

Packaging-associated proteins

In the four similar Acinetobacter baumannii phages, the genetic elements encoding the products involved in the packaging system are commonly found adjacent to one another in the phage genomes. Packaging system is generally composed of big subunit (CDS.27) and small subunit (CDS.28). Usually, the two subunits of the terminase and head portal protein (CDS.26) are closely connected in the packaging system, while the portal protein is a bacteriophage component that forms a hole, or portal, enabling DNA passage during packaging and ejection [20]. It also forms the junction between the phage head (capsid) and the tail proteins.

Discussion

With the emergence of a growing number of drug-resistant bacterial species, and the difficulties surrounding the development of novel antibiotics [21], exploring novel or alternative therapeutic methods is imperative. The recent renaissance of bacteriophage therapy may provide new treatment strategies for combatting drug-resistant bacterial infections. Although a large number of work on phage therapy in human disease had been done [22-24], the host-specific infection and the relatively narrow lytic spectrum of phage is one of the obstacles to their further application. Individualized phage therapy may represent the future of phage therapy, where bacterial infections will be treated with phage combinations that have already been shown as effective for that particular bacterium. To overcome these limitations, strategies such as screening more lytic phages, combining phages with antibiotics, or administrating phages cocktails should be investigated [25,26]. Therefore, it is very important to isolate novel and sensitive phages to enrich the phage arsenal [27].

All known Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophages were summarized and compared in this research. There are nearly 20 A. baumannii phage strains reported in the literature mainly in 2012. Most of the phages genome length are about 40 kb. Just only thirteen complete A. baumannii phage genomes were sequenced and deposited in the GenBank database currently. Five of those genomes consist of an approximately 160 kb linear DNA molecule (Acinetobacter phage Ac42,Acj61,Acj9,133,and ZZ1), and are annotated as T4-like phage [5,28]. The remaining eight phages contain a genome of 30–50 kb, and may be classified into two different groups according to sequence similarity. In one group, there are four phages with a linear genome, including phiAB1, which was already classified as a ϕKMV-like virus [29], phage YMC/09/02/B1251_ABA_BP [30], Acinetobacter phage AB3 and Acinetobacter phage Abp1. The other group includes four phages: AB1 (GenBank accession number: HM368260), AP22 (GenBank accession number: HE806280), phiAC-1 (GenBank accession number: JX560521), and our phage IME-AB2. We compared the growth characteristics and the genome of A. baumannii phage as shown in Table 4. The results indicated that the newly isolated phage IME-AB2 has a shorter latent and burst period than AB1 and AP22, which implied that the IME-AB2 was more lytic and the burst size produced by IME-AB2 was smaller than those phages [31]. All the listed A. baumannii bacteriophages or its lysin had been tested in treating bacterial infection such as inhibiting biofilm formation or effecting on host cell survival. Although the bacteriophage IME-AB2 could lyse the host bacteria and cleared the bacterial suspension in 4 hours, we observed that the resistant bacteria appeared and made the suspension turbid again in 24 hours. The easily emerging resistant bacteria after infection with phage might be an obstacle when fighting against bacterial infection with bacteriophage in the future.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of all known Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophages

| Name | Morphology | Genetic material | Genomic length | G C content (%) | Major protein sizes | Adsorption time (>99%) | latent period | Burst size (PFU/cell) | Spectrum | Published time | Isolation | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IME-AB2 |

Myoviridae |

circular dsDNA |

43665 bp |

37.5 |

38 kDa (35–130 kDa) |

9 min |

20 min |

62 |

3 of 22 |

|

hospital sewage, Beijing,China |

|

| AB1

[32] |

Caudovirales |

circular dsDNA |

45159 bp |

37.7 |

33.1 kDa (14.4–97.4 kDa) |

|

85 min |

232 |

|

2012 |

Wenzhou,China |

|

| AP22

[33] |

Myoviridae |

circular dsDNA |

46387 bp |

|

32 kDa (18–87 kDa) |

5 min |

40 min |

240 |

89 of 130 |

2012 |

Clinical material, Russia |

|

| phiAC-1

[34] |

Myoviridae |

circular dsDNA |

43216 bp |

38.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

2012 |

First phage infect A. soli,South Korea |

|

| AB7-IBB2

[35] |

Podoviridae |

dsDNA |

170 kb |

|

|

4 min |

25 min |

|

19 of 39 |

2012 |

India |

Inhibit host biofilm formation |

| AB7-IBB1

[36] |

Siphoviridae |

dsDNA |

75 kb |

|

14.3-43 kDa |

5 min |

30 min |

125 |

23 of 39 |

2012 |

India |

Inhibit host biofilm formation |

| ZZ1

[5] |

Myoviridae |

linear dsDNA |

166682 bp |

34.3 |

|

|

9 min |

200 |

3 of 23 |

2012 |

fishpond water, Zhenzhou, China |

|

| Abp1

[37] |

Podoviridae,phiKMV-like,T7 group |

linear dsDNA |

42185 bp |

39.15 |

29 kDa–116 kDa |

|

10 min |

350 |

narrow |

2012 |

Chongqing, China |

|

| AB3

[38] |

cubic phage |

linear dsDNA |

31185 bp |

|

35 kDa (35–264 kDa) |

|

20 min |

350 |

wide |

2012 |

Chongqing, China |

|

| YMC/09/ 02/B1251 ABA BP

[30] |

Podoviridae |

linear dsDNA |

45364 bp |

39.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

2012 |

South Korea |

|

| phikm18p

[39] |

cubic phage |

dsDNA |

45 kb |

|

39 kDa |

|

|

|

wide |

2012 |

Taiwan |

Cell survival test |

| ABp53

[40] |

Myoviridae |

dsDNA |

95 kb |

|

47-kDa protein |

|

10 min |

150 |

27% |

2011 |

Sputum,Taiwan |

|

| phiAB1

[29] |

Podoviridae, phiKMV-like phages |

linear dsDNA |

41526 bp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2011 |

Taiwan |

|

| Ac42,Acj61,Acj9,133

[28] |

T4 |

linear dsDNA |

160 kb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2010 |

USA |

|

| AB1

[41] |

Siphoviridae family |

dsDNA |

45.2 kb to 46.9 kb |

|

14 to 80 kilo-dalton |

|

18 min |

409 |

narrow |

2010 |

Marine sediment, Taiwan |

|

| phi AB2 [42] | Podoviridae, phiKMV-like phages | dsDNA | 40 kb | 8 min | 10 min | 200 | wide | 2010 | Taiwan | Lyase AB2 |

Conclusions

A lytic A. baumannii bacteriophage IME-AB2 was isolated and characterized in this research. The complete genome of IME-AB2 was sequenced and compared to those of A. baumannii phage AB1, A. baumannii phage AP22, and A. baumannii phage phiAC-1 in detail. The genome of IME-AB2 was replete with novel genes without known relatives, which indicated that IME-AB2 was a novel and unique A. baumannii bacteriophage. Although the resistant A. baumannii appeared finally after infection with IME-AB2, the comprehensive understanding of the phage’s characteristics is conducive to the treatment of multidrug-resistant A. baumannii in the future.

Methods

Bacterial strains, Phage isolation, propagation, and titration

This study included 22 clinical strains of A. baumannii (MDR-AB1139, MDR-AB1, MDR-AB2, MDR-AB3, MDR-AB4, MDR-AB5, … , MDR-AB19,MDR-AB20, MDR-AB21). All the clinical samples were taken as part of standard patient care at the PLA Hospital 307, Beijing, China. The patients were orally informed that the specimens would be used for screening bacteria and the tests were optional on laboratory sheet. Blood, sputum and skin swabs were collected from patients with consent under the Ethics Committee of the PLA Hospital 307. The protocol of screening bacteria was approved by the Ethics Committee of the PLA Hospital 307 and Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology Ethics Committee.

Multidrug-resistant A. baumannii strain MDR-AB2 was used as an indicator for bacteriophage screening of raw sewage samples collected from PLA Hospital 307. Sewage samples were separated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min. Following removal of the solid impurities by centrifugation, the supernatants were filtered through a 0.45 μm pore-size membrane filter to remove bacterial debris. Filtrate (4 ml) was added to 2 ml of 3× Luria-Bertani (LB) broth medium and mixed with 0.1 ml of A. baumannii overnight culture (OD600 = 0.6) to enrich the phage at 37°C overnight. Following enrichment, the culture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and then the supernatant was filtered with a 0.45 μm pore-size membrane filter to remove the residual bacterial cells. The filtrate (0.1 ml) was mixed with 0.5 ml of A. baumannii in LB culture (OD600 = 0.6) and 5 ml of molten top soft nutrient agar (0.75% agar), which was then overlaid onto solidified base nutrient agar (1.5% agar) [43]. Following incubation for 6 h at 37°C, the clear phage plaques were picked from the plate. The phage titer was determined using the double-layered method previously described by Adams [44].

Phage concentration , purification and storage

A single plaque was picked into 5 ml of LB medium containing MDR-AB2 (OD600 = 0.6) and cultured at 37°C for 6 h. A 5 ml aliquot of suspension was transferred into 500 ml of LB medium for culture at 37°C overnight. Chloroform was then added to the 500 ml of culture to a final concentration 0.1% before being mixed gently and allowed to stand at room temperature for about 30 min. Solid NaCl was added to the culture to a final concentration of 1 M, which was then incubated in an ice water bath for 1 h. The culture was centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris, and polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG6000) was added to the supernatant to a final concentration of 10% (w/v) while slowly stirring with a magnetic stirrer at room temperature. This solution was transferred to a polypropylene centrifuge tube in an ice water bath and incubated at least 1 h to precipitate the phage particles. Following centrifugation (11,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), the phage-containing precipitate was resuspended in 5 ml of SM buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, pH 7.5) [45]. An equal volume of chloroform was then added to separate the phage particles from PEG6000. Following centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min, the aqueous phase was recovered and filtered through a 0.22 μm pore-size membrane filter to remove debris. The concentrated 1.0 ml of phage suspensions were layered on the top of a cesium chloride gradient solutions (density of 1.3 g/ml-0.45 g of cesium chloride in 1.0 ml of water; density of 1.5 g/ml-0.83 g of cesium chloride in 1.0 ml of water; density of 1.7 g/ml-1.28 g of cesium chloride in 1.0 ml of water) in 5.0 ml cellulose nitrate centrifuge tube [46]. After centrifugation in a Beckman Coulter Swinging Bucket Rotor (SW41, Ti) for 40 min at 100,000 × g, the concentrated phages at the visible band were collected by means of a capillary pipette. The purified phage was stored at 4°C.

Determination of lytic spectrum

The host range was determined by spot test. Briefly, 0.5 ml of bacterial overnight culture was mixed with 5 ml of molten top soft nutrient agar (0.75% agar) and then overlaid on the surface of solidified base nutrient agar (1.5% agar). Once the top layer also solidified, 2 μl of the phage preparation(1 × 109 pfu/ml) was spotted onto the plate, which was incubated for 6 h at 37°C.

Electron microscopy

Phage stock solution was directly stained with phosphotungstic acid (PTA) for 2 min. After being dried at room temperature, the grid was examined using a Philips TECNAI-10 transmission electron microscope (TEM) to observe and record the morphology of the phage particles [41].

Extraction of phage genomic DNA

Purified phage particles were treated with DNase I (1 μg/ml) (Takara) and RNase A (1 μg/ml) (Takara) for 30 min, and then the nucleases were inactivated at 80°C for 15 min. Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) (20 mM), proteinase K (50 μg/ml) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (0.5%) were then added and the mixture was incubated at 56°C for 1 h. Phage lysate was extracted with an equal volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). Chloroform extraction was repeated until there was no phenol odor. An equal volume of isopropanol (AR grade) was added and the sample was incubated overnight at -20°C to precipitate the phage genomic DNA. The pellet was washed with 75% ethanol, and then deionized water was used to dissolve the precipitated genomic DNA.

Whole genome sequence and bioinformatics analysis

The genomic DNA of IME-AB2 was subjected to high-throughput sequencing using a Life Technologies Ion Personal Genome Machine Ion Torrent sequencer (San Francisco, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The complete genome sequence of phage IME-AB2 was assembled using Velvet [47] and CLC Bio (Aarhus, Denmark), and annotated using RAST [48] and InterPro [49]. Sequence similarity analysis and comparison were performed using NCBI packages.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Fan Peng isolated the phage, identified the characterization, and drafted the manuscript. Zhiqiang Mi and Yong Huang were responsible for sequencing and drafting the manuscript. Wenkai Niu and Xin Yuan collected clinical bacteria. Yahui Wang conducted the phage concentration and purification. Yuhui Hua and Huahao Fan conducted EM assay. Yigang Tong and Changqing Bai conceived and designed the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Fan Peng, Email: 290654382@qq.com.

Zhiqiang Mi, Email: zhiqiangmi.ime@gmail.com.

Yong Huang, Email: yong.huang1987@gmail.com.

Xin Yuan, Email: xinyuannatile@sina.com.

Wenkai Niu, Email: fancy3232@163.com.

Yahui Wang, Email: 270235414@qq.com.

Yuhui Hua, Email: yuhui_hua@126.com.

Huahao Fan, Email: fanhuahao.1987@163.com.

Changqing Bai, Email: mlp1604@sina.com.

Yigang Tong, Email: tong62035@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81072350), the National Hi-Tech Research and Development (863) Program of China (No. 2012AA022-003), the China Mega-Project on Major Drug Development (No. 2011ZX09401-023), the China Mega-Project on Infectious Disease Prevention (No. 2013ZX10004-605 and No. 2011ZX10004-001), the State Key Laboratory of Pathogen and BioSecurity Program (No. SKLPBS1113), and the Particular Clinical Applied Research of the Capital of China (No.Z121107001012127).

Nucleotide sequence accession number: The whole-genome sequence of phage vB_AbaM-IME-AB2 has been deposited in the NCBI nucleotide sequence database under GenBank assession number: JX976549.

References

- Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2007;51(10):3471–3484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE. Pandrug resistance (PDR), extensive drug resistance (XDR), and multidrug resistance (MDR) among Gram-negative bacilli: need for international harmonization in terminology. Clinical infectious diseases. 2008;46(7):1121–1122. doi: 10.1086/528867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas ME, Koletsi PK, Bliziotis IA. The diversity of definitions of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and pandrug-resistant (PDR) Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of medical microbiology. 2006;55(12):1619–1629. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2008;21(3):538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Li ZJ, Wang SW, Wang SM, Huang DH, Li YH, Ma YY, Wang J, Liu F, Chen XD. Isolation and characterization of ZZ1, a novel lytic phage that infects Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. BMC microbiology. 2012;12(1):156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2001;45(3):649–659. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.649-659.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan EM, Gorman SP, Donnelly RF, Gilmore BF. Recent advances in bacteriophage therapy: how delivery routes, formulation, concentration and timing influence the success of phage therapy. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2011;63(10):1253–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropinski AM, Prangishvili D, Lavigne R. Position paper: the creation of a rational scheme for the nomenclature of viruses of Bacteria and Archaea. Environmental microbiology. 2009;11(11):2775–2777. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra CK, Choi TJ, Kang SC. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriophage F20 virulent to Enterobacter aerogenes. J Gen Virol. 2012;93(Pt 10):2310–2314. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Mi Z, Yin X, Fan H, An X, Zhang Z, Chen J, Tong Y. Characterization of Enterococcus faecalis phage IME-EF1 and its endolysin. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadagkar R, Gopinathan K. Bacteriophage burst size during multiple infections. Journal of Biosciences. 1980;2(3):253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Moriyama EN. Vector NTI, a balanced all-in-one sequence analysis suite. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2004;5(4):378–388. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Jiang H, Li C, Wang S, Mi Z, An X, Chen J, Tong Y. Sequence characteristics of T4-like bacteriophage IME08 benome termini revealed by high throughput sequencing. Virology Journal. 2011;8(1):194. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seed KD, Bodi KL, Kropinski AM, Ackermann HW, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Camilli A. Evidence of a dominant lineage of Vibrio cholerae-specific lytic bacteriophages shed by cholera patients over a 10-year period in Dhaka, Bangladesh. MBio. 2011;2(1):e00334–00310. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00334-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranquet C, Ollagnier-de-Choudens S, Loiseau L, Barras F, Fontecave M. Cobalt Stress in Escherichia coli THE EFFECT ON THE IRON-SULFUR PROTEINS. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(42):30442–30451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702519200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Schneider TD. Information theory based T7-like promoter models: classification of bacteriophages and differential evolution of promoters and their polymerases. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(19):6172–6187. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Anantharaman V, Balaji S, Babu MM, Iyer LM. The many faces of the helix-turn-helix domain: transcription regulation and beyond. FEMS microbiology reviews. 2005;29(2):231–262. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R, Kunin V, Hugenholtz P. CRISPR—a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6(3):181–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MJ, Henning U. The immunity (imm) gene of Escherichia coli bacteriophage T4. Journal of virology. 1989;63(8):3472–3478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.8.3472-3478.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Rao VB, Black LW. Analysis of capsid portal protein and terminase functional domains: interaction sites required for DNA packaging in bacteriophage T4. Journal of molecular biology. 1999;289(2):249–260. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirisi A. Phage therapy—advantages over antibiotics? The Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abedon ST, Kuhl SJ, Blasdel BG, Kutter EM. Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage. 2011;1(2):66–85. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.2.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alisky J, Iczkowski K, Rapoport A, Troitsky N. Bacteriophages show promise as antimicrobial agents. Journal of Infection. 1998;36(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)92874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Dabrowska B, Mulczyk M, Górski A. Bacteriophage therapy for infections in cancer patients. Clinical and Applied Immunology Reviews. 2001;1(3):131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Merabishvili M, Pirnay JP, Verbeken G, Chanishvili N, Tediashvili M, Lashkhi N, Glonti T, Krylov V, Mast J, Van Parys L. Quality-controlled small-scale production of a well-defined bacteriophage cocktail for use in human clinical trials. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):e4944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Johnson R, Xu Y, McAllister T, Sharma R, Louie M, Stanford K. Host range and lytic capability of four bacteriophages against bovine and clinical human isolates of Shiga toxin‒producing Escherichia coli O157: H7. Journal of applied microbiology. 2009;107(2):646–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane FT, Claire P, Matthew JH. Isolation of Bacteriophage against Currently Circulating Strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Journal of Medical Microbiology & Diagnosis. 2012;1:109. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliy P, Swarnamala R, James N, Jim K. Genomes of the T4-related bacteriophages as windows on microbial genome evolution. Virology Journal. 2010;7:292. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KC, Lin NT, Hu A, Lin YS, Chen LK, Lai MJ. Genomic analysis of bacteriophage ϕAB1, a ϕKMV-like virus infecting multidrug-resistant. Acinetobacter baumannii. Genomics. 2011;97(4):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J, Kim J, Yong D, Lee K, Chong Y. Complete Genome Sequence of the Podoviral Bacteriophage YMC/09/02/B1251 ABA BP, Which Causes the Lysis of an OXA-23-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolate from a Septic Patient. Journal of virology. 2012;86(22):12437–12438. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02132-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abedon ST. Selection for bacteriophage latent period length by bacterial density: a theoretical examination. Microbial Ecology. 1989;18(2):79–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02030117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Chen B, Song Z, Song Y, Yang Y, Ma P, Wang H, Ying J, Ren P, Yang L. Bioinformatic analysis of the Acinetobacter baumannii phage AB1 genome. Gene. 2012;507(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova AV, Zhilenkov EL, Myakinina VP, Krasilnikova VM, Volozhantsev NV. Isolation and characterization of wide host range lytic bacteriophage AP22 infecting Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS microbiology letters. 2012;332(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Oh C, Choresca CH, Shin SP, Han JE, Jun JW, Heo S-J, Kang D-H, Park SC. Complete Genome Sequence of Bacteriophage phiAC-1 Infecting Acinetobacter soli Strain KZ-1. Journal of virology. 2012;86(23):13131–13132. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02454-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thawal ND, Yele AB, Sahu PK, Chopade BA. Effect of a novel podophage AB7-IBB2 on Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm. Current microbiology. 2012;65(1):66–72. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yele AB, Thawal ND, Sahu PK, Chopade BA. Novel lytic bacteriophage AB7-IBB1 of Acinetobacter baumannii: isolation, characterization and its effect on biofilm. Archives of virology. 2012;157(8):1441–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Le S, Peng Y, Zhao Y, Yin S, Zhang L, Yao X, Tan Y, Li M, Hu F. Characterization and Genome Sequencing of Phage Abp1, a New phiKMV-Like Virus Infecting Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Current microbiology. 2013;66(6):535–543. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie Z, Xi L, Dan G. Sequencing and bioinformatic analysis of genome of Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophage AB3. Journal of Third Military Medical University. 2013;15:008. [Google Scholar]

- Shen G-H, Wang J-L, Wen F-S, Chang K-M, Kuo C-F, Lin C-H, Luo H-R, Hung C-H. Isolation and Characterization of φkm18p, a Novel Lytic Phage with Therapeutic Potential against Extensively Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e46537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-N, Tseng T-T, Lin J-W, Fu Y-C, Weng S-F, Tseng Y-H. Lytic myophage Abp53 encodes several proteins similar to those encoded by host Acinetobacter baumannii and phage phiKO2. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2011;77(19):6755–6762. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05116-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Liang L, Lin S, Jia S. Isolation and characterization of a virulent bacteriophage AB1 of Acinetobacter baumannii. BMC microbiology. 2010;10(1):131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N-T, Chiou P-Y, Chang K-C, Chen L-K, Lai M-J. Isolation and characterization of AB2: a novel bacteriophage of Acinetobacter baumannii. Research in microbiology. 2010;161(4):308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germida JJ, Casida L Jr. Ensifer adhaerens predatory activity against other bacteria in soil, as monitored by indirect phage analysis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1983;45(4):1380–1388. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.4.1380-1388.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MH, Comroe JH, Venning E. Methods of Study of Bacterial Viruses. Year Book Publishers; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Hezwani M, Nelson S, Salisbury V, Reynolds D. Characterization of the Salmonella bacteriophage vB_SenS-Ent1. J Gen Virol. 2012;93(Pt 9):2046–2056. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach U, Friedmann A. Practical procedures for the purification of bacterial viruses. Appl Microbiol. 1971;22(4):706–715. doi: 10.1128/am.22.4.706-715.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome research. 2008;18(5):821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz R, Bartels D, Best A, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards R, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass E, Kubal M. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC genomics. 2008;9(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder NJ, Apweiler R. The InterPro database and tools for protein domain analysis. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2008;2.7:1–2.7. 18. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0207s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]