In March 2010, the government announced its Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) initiative for England, which aimed to make £20 billion of efficiency savings in the NHS by 2015.1 The scheme calls for reduction in hospital-based care through an increase in care closer to home, efficiency through new technology and innovation through medical research.2

As with most industrialised nations, the UK population is living longer; in 2010, there were 19 million individuals over the age of 60 years and this number is predicted to increase to 28 million by 2035.3 While evidence suggests that most people are enjoying more healthy older age now than ever before, older people are still at a greater risk of developing disease and remain disproportionate users of healthcare services.4 Within ophthalmology, there is an increase in prevalence of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR) and glaucoma, all of which are potentially blinding conditions that frequently require lifelong monitoring, and often treatment, to prevent irreversible visual loss.5, 6, 7, 8

Use of hospital outpatient services for ophthalmology ranked second only to orthopaedics and trauma (6.3 vs 7.1 million outpatient appointments in 2011–12, respectively). Hospital eye care accounts for 8.6% of all outpatient activity in NHS England. For example, at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, glaucoma and medical retina follow-up appointments constituted 146 707 attendances over the 2011–12 period, accounting for 45% of all follow-up attendances across the Trust. With the 2014–15 National Tariff Payment System recommending prices for ophthalmology out-patient services at ∼£100 for new patients and ∼£85 for follow-up consultant-led attendances,9 these attendances represent a major and ever-increasing cost burden. Total costs will only increase when we consider the implementation of the 2009 NICE guidelines, which prompted a considerable increase in the number of glaucoma-suspect referrals,10, 11 the advent of new treatments (such as anti-VEGF injections) for AMD,12 and, more recently, DR,13 which requires regular administration and patient monitoring by ophthalmologists.

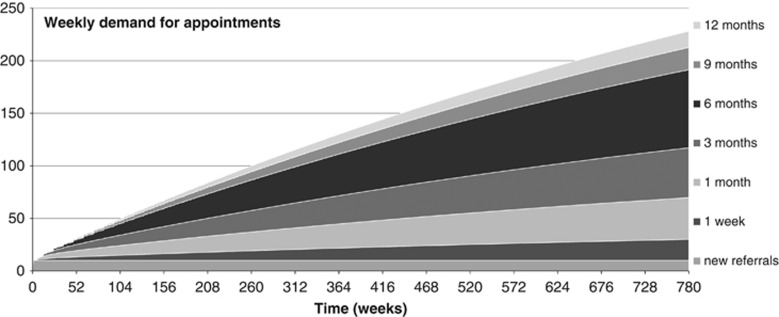

The increasing prevalence of chronic eye diseases, increasingly widespread use of diagnostic technology by optometrists, and the chronicity of these conditions have been taken into consideration by some hospital eye departments to predict capacity problems in meeting the demand for ophthalmology out-patient services.14, 15, 16 To illustrate this, we have developed a model based on appointment interval outcome data obtained from patients attending the Glaucoma Service at Moorfields Eye Hospital between 1 April and 30 June 2013. The model starts from 0 patients and assumes a stable stream of 10 new referrals per week for one consultant's clinic. The case mix includes complex, unstable or surgical cases, and stable patients. The data obtained suggest that ∼30% of new referrals to the clinic and 8% of those on 12-month interval are discharged, with a much smaller discharge rate for those under the service for shorter follow-up periods. Figure 1 illustrates the predicted weekly demand for appointments in this new consultant's service over a 15-year period.

Figure 1.

Projected weekly demand (number of patients) for an outpatient glaucoma clinic based on retrospective data obtained from Moorfields Eye Hospital glaucoma service over a 3-month period. The interval for follow-up appointment in the new clinic ranges from a single week to 12 months, and there are 10 new referrals to the clinic every week.

Secondary care providers are under increasing pressure to keep new to follow-up ratios at or less than 1 : 2.5, with penalties being imposed if targets are not met.17 However, ophthalmology departments often have very different new to follow-up ratios18 as patients with chronic eye disease cannot be discharged to a primary care setting. Guidelines that outline the recommended intervals for patient monitoring have been developed to ensure that patients are monitored at intervals appropriate to their risk of disease progression and visual loss.19, 20 Bringing patients back too frequently increases the demand for appointments and may result in overbooked clinics, which in turn may lead to inappropriate appointment rescheduling. Delays in appointments have implications for patient safety.21, 22

There are a number of approaches to meeting the increasing demand for services. One is to increase clinic capacity,23 which, although may in the short term lead to a reduction of waiting times, is not be a viable long-term solution (as Figure 1 demonstrates). Another is to implement community eye care schemes, whereby ‘stable' patients may be discharged from secondary care to be followed up within the community, usually by suitably trained optometrists. While there has been a drive towards this model of care,24 anecdotal evidence suggests that the success of such schemes is very much dependent on a high level of secondary care input and overall supervision.25 Furthermore, there is a concern that moving care from secondary to primary settings may be at the expense of care quality and that costs for such services are often greater than expected.26, 27 While there are a number of successful community models of primary care ophthalmology that improve the quality of new referrals into secondary care,28, 29, 30, 31, 32 there is a scarcity of evidence concerning the viability of community monitoring services for people with stable eye diseases. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that non-attendances to non-ophthalmologist-led community services are greater than those in NHS secondary care settings.33

Even with such community schemes, there will always be a number of patients who are not suitable for, or who do not want, community monitoring. These patients need to be managed efficiently within the acute NHS setting.

In the care of chronic ophthalmic disease, the patient journey time per outpatient appointment can be lengthy34 and depends on the number of pre-consultation monitoring tests and the availability of tests/staff on the day. Recommended guidelines for frequency of testing are often not followed due to time constraints within busy outpatient settings,35 which may be detrimental to the patient. While regular patient monitoring is necessary, there is no doubt that a more efficient approach to patient care is required if the hospital eye service is to cope with increasing demand.

Efficiency may sometimes be misinterpreted as a 100% utilisation of resources.23, 36 This approach can lead to an increase in ‘time wastage', whereby time is wasted triaging, prioritizing, and managing patients rather than being used to diagnose and treat patient conditions. A more efficient use of resources would be to reorganize patient flow through the system. Patient flow describes the flow of patients between staff, departments, and organizations through the care pathway. Poor patient flow increases the likelihood of harm to patients and increases healthcare costs when ‘unnecessary' processes waste precious resources.37

The issue of optimizing patient flow through ophthalmology clinics is not new and is being addressed by NHS and independent sector providers. As an example, The Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield has for over 20 years run a virtual Glaucoma Monitoring Unit for stable glaucoma patients, staffed by technicians. The service removes the face-to-face ophthalmologist consultation and data are reviewed remotely by a consultant ophthalmologist (S Longstaff, personal communication, 15 January 2014). The average patient journey time is 40 min, with a review/GP and patient information turnaround of 2 weeks. A similar model for glaucoma care is run by an independent sector provider,38, 39 although this model utilizes specialist trained optometrists for the face-to-face consultation, with consultant ophthalmologist remote review of data to ratify clinical decisions. Both services make use of the electronic patient record (EPR) to deliver their service. Whilst the ‘virtual' approach has been used to facilitate specialist ophthalmological consultation in remote areas,40, 41 these examples support the possibility of removing some face-to-face doctor consultations as a more efficient way to manage some patients within the NHS.42

The NHS Operating Framework 2012–13 encourages clinical commissioning groups to adopt innovation within their local reconfiguration plans, and cites removal of the face-to-face consultation as an efficient method to deliver care.43 The use of this type of model remains contentious, may have unintended consequences, and needs to be assessed alongside, and relative to, other interventions to improve quality and efficiency.44, 45

Within the NHS, implementation of redesigned services may be inhibited by a lack of clinical engagement due to disagreement about their purpose, resistance to standardisation, and their perceived relevance to only some clinical groups.46 There may be difficulties with aligning different managerial and clinical groups in the context of clinical service redesign,47, 48 as well as changing inter-professional relationships.49 A further barrier to the success of any new NHS care pathway is a lack of evidence on effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, viability, sustainability, safety, and acceptability to patients and clinicians. The approach to such evaluations should combine the question ‘what works, at what cost?' with a study of the development, implementation, and sustainability of these models, including the views of the multiple stakeholders likely to be affected by the implementation.50, 51 Ongoing evaluation of services, which may include non-participant observation or ethnographic methods,52 coupled with analysis of outcomes, costs, and modelling should be used to identify aspects of the organisational context that influence the implementation of change and to support the iterative development of services that builds on such evidence.

In the current climate of increasing demand and limited clinic capacity, radical change in provision is needed, but without good-quality evidence, NHS ophthalmology providers will remain divided in their approach to the care of chronic eye disease. Ophthalmology services are in critical need of robust evaluation to determine which clinical pathways best suit the increasing demand for services. Without evaluation, we run the risk of taking distinctly disparate approaches to care, with little idea of what is best for the patient.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Special Trustees of Moorfields Eye Hospital, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital, and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. We wish to thank Benjamin White, Performance Manager at Moorfields Eye Hospital, for providing the outpatient data statistics used in this paper, Dr Baris Yalabik, University of Bath, for work on the spreadsheet model, and Mr Simon Longstaff, Consultant Ophthalmologist at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital, for information regarding his stable monitoring service. Dr Kotecha and Professor Foster receive a proportion of their funding from the Department of Health's National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Department of Health. The NHS quality, innovation, productivity and prevention challenge: an introduction for clinicians,11 March 2010 . http://somaxa.com/docs/file/QIPP_2010.pdf .

- Department of Health. Making the NHS more efficient and less bureaucratic, 25 March 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/making-the-nhs-more-efficient-and-less-bureaucratic .

- Office for National Statistics. National Population Projections, 2010-Based Statistical Bulletin, 26 October 2011. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_235886.pdf .

- Rice DP, Fineman N. Economic implications of increased longevity in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:457–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90 (3:262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngai LY, Stocks N, Sparrow JM, Patel R, Rumley A, Lowe G, et al. The prevalence and analysis of risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: 18-year follow-up data from the Speedwell eye study, United Kingdom. Eye (Lond) 2011;25 (6:784–793. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian DC, Reidy A, Lightstone A, Desai P. Modelling the prevalence of age-related macular degeneration (2010-2020) in the UK: expected impact of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95 (10:1433–1436. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.195370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian DC, Owens DR, Reidy A. Prevalence of diabetic macular oedema and related health and social care resource use in England. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96 (3:345–349. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2011.204040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monitor. 2014/15 National Tariff Payment System: Annex 5A—National prices, 17 December 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-tariff-payment-system-2014-to-2015 .

- Shah S, Murdoch IE. NICE—impact on glaucoma case detection. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011;31 (4:339–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva SR, Riaz Y, Purbrick RM, Salmon JF. There is a trend for the diagnosis of glaucoma to be made at an earlier stage in 2010 compared to 2008 in Oxford, United Kingdom. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2013;33 (2:179–182. doi: 10.1111/opo.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetta P, Mitchell P, Wolf S, Veritti D. Different antivascular endothelial growth factor treatments and regimens and their outcomes in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a literature review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97 (12:1497–1507. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LQ, Zhu H, Zhao PQ, Hu YQ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes of vitrectomy with or without intravitreal bevacizumab pretreatment for severe diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95 (9:1216–1222. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.189514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalk D, Smith M. Guidelines on glaucoma and the demand for services. Br J Healthc Manage. 2013;19 (10:476–481. [Google Scholar]

- RNIB. Saving money, losing sight. RNIB campaign report, November 2013. http://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/Saving%20money%20losing%20sight%20executive%20summary.pdf .

- Smith R.Our OphthalmologyService is ‘Failing', Please Help! Professional Standards Committee: London, UK, 2013.

- Royal College of Ophthalmologists Professional Standards Committee: PROF/2011/114. New to Followup Ratios in Ophthalmology Outpatient Services, London, UK,2011

- Sparrow JM. How nice is NICE. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97 (2:116–117. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE. National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance CG85. Glaucoma: diagnosis and management of chronic open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension, April 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG85 .

- RCOphth. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists—Age-related Macular Degeneration: Guidelines for Management, September 2013. http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=451 .

- Tatham A, Murdoch I. The effect of appointment rescheduling on monitoring interval and patient attendance in the glaucoma outpatient clinic. Eye (Lond) 2012;26 (5:729–733. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Patient Safety Agency. Preventing Delay to Follow-Up for Patients with Glaucoma. National Patient Safety Agency: London, 2009.

- Silvester K, Lendon R, Bevan H, Steyn R, Walley P. Reducing waiting times in the NHS: is lack of capacity the problem. Clin Manage. 2004;12 (3:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: A New Direction for Community Services. Department of Health: London, 2006.

- McLeod H, Dickinson H, Williams W, Robinson S, Coast J.Evaluation of the Chronic Eye Care Services Programme: Final Report. RNIB/University of Birmingham, 2006. www.eyecare.nhs.uk/uploads/ChronicEyecareServicesProgramme.doc .

- Coast J, Spencer IC, Smith L, Spry PG. Comparing costs of monitoring glaucoma patients: hospital ophthalmologists versus community optometrists. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1997;2 (1:19–25. doi: 10.1177/135581969700200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibbald B, McDonald R, Roland M. Shifting care from hospitals to the community: a review of the evidence on quality and efficiency. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12 (2:110–117. doi: 10.1258/135581907780279611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazawy S, Saldana M, McKibbin M.Patient pathways for macular disease: what will the new optometrist with special interest achieve Eye (Lond) 200721(4553–554.(author reply 552-3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkins DJ, Edgar DF. Comparison of the effectiveness of two enhanced glaucoma referral schemes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011;31 (4:343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trikha S, Macgregor C, Jeffery M, Kirwan J. The Portsmouth-based glaucoma refinement scheme: a role for virtual clinics in the future. Eye (Lond) 2012;26 (10:1288–1294. doi: 10.1038/eye.2012.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoaku W, Blakeney S, Freeman M, Gale R, Johnston R, Kelly SP, et al. Action on AMD. Optimising patient management: act now to ensure current and continual delivery of best possible patient care. Eye (Lond) 2012;26 (Suppl 1:S2–S21. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnarajan G, Newsom W, Vernon SA, Fenerty C, Henson D, Spencer F, et al. The effectiveness of schemes that refine referrals between primary and secondary care—the UK experience with glaucoma referrals: the Health Innovation & Education Cluster (HIEC) Glaucoma Pathways Project. BMJ Open. 2013;3 (7:e002715. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandalos A, Bourne R, French K, Newsom W, Chang L. Shared care of patients with ocular hypertension in the Community and Hospital Allied Network Glaucoma Evaluation Scheme (CHANGES) Eye (Lond) 2012;26 (4:564–567. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen FC, Baker H, Crabb DP. A qualitative investigation into patients' views on visual field testing for glaucoma monitoring. BMJ Open. 2014;4 (1:e003996. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik R, Baker H, Russell RA, Crabb DP. A survey of attitudes of glaucoma subspecialists in England and Wales to visual field test intervals in relation to NICE guidelines. BMJ Open. 2013;3:5. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allder S, Walley P, Silvester K. Is follow-up capacity the current NHS bottleneck. Clin Med. 2011;11 (1:31–34. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-1-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, TH. Improving Patient Flow: Learning Report. Foundation, TH.: London, 2013.

- Diamond J.Waiting times in glaucoma care. Health Serv J 2010; e-pub ahead of print 28 May 2010.

- Havard J.A mobile clinic for glaucoma patients. Pulse Today 2013; e-pub ahead of print 26 February 2013.

- Hautala N, Hyytinen P, Saarela V, Hägg P, Kurikka A, Runtti M, et al. A mobile eye unit for screening of diabetic retinopathy and follow-up of glaucoma in remote locations in northern Finland. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87 (8:912–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassam F, Amin S, Sogbesan E, Damji KF. The use of teleglaucoma at the University of Alberta. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18 (7:367–373. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuulonen A. Challenges of glaucoma care—high volume, high quality, low cost. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91 (1:3–5. doi: 10.1111/aos.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. The operating framework for the NHS England 2012/13, 24 November 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo ads/attachment_data/file/216590/dh_131428.pdf .

- Jacklin PB, Roberts JA, Wallace P, Haines A, Harrison R, Barber JA, et al. Virtual outreach: economic evaluation of joint teleconsultations for patients referred by their general practitioner for a specialist opinion. BMJ. 2003;327 (7406:84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7406.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornall J. Does telemedicine deserve the green light. BMJ. 2012;345:e4622. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S, Jarrett M, McCrone P, Thornicroft G. Facilitators and barriers to implementing clinical care pathways. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:182. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Sweeney K. Doctors and managers. "You just don't understand". BMJ. 2003;326 (7390:656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall MN. Doctors, managers and the battle for quality. J R Soc Med. 2008;101 (7:330–331. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.nh8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram DV, Culham LE. Ophthalmologists and optometrists—interesting times. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85 (7:769–770. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster Aj. Health Technology and Society. A Sociological Critique. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fulop N, Boaden R, Hunter R, McKevitt C, Morris S, Pursani N, et al. Innovations in major system reconfiguration in England: a study of the effectiveness, acceptability and processes of implementation of two models of stroke care. Implement Sci. 2013;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Bosk CL, Aveling EL, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Explaining Michigan: developing an ex post theory of a quality improvement program. Milbank Q. 2011;89 (2:167–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]