Abstract

After the improvement in arthroscopic shoulder surgery, superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears are increasingly recognized and treated in persons with excessive overhead activities like throwers. Several potential mechanisms for the pathophysiology of superior labral tears have been proposed. The diagnosis of this condition can be possible by history, physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging combination. The treatment of type 1 SLAP tears in many cases especially in older patients is non-operative but some cases need arthroscopic intervention. The arthroscopic management of type 2 lesions in older patients can be biceps tenodesis, but young and active patients like throwers will need an arthroscopic repair. The results of arthroscopic repair in older patients are not encouraging. The purpose of this study is to perform an overview of the diagnosis of the SLAP tears and to help decision making for the surgical management.

Keywords: Superior labrum anterior to posterior tear, Glenoid labrum, Arthroscopy, Repair, Shoulder

Core tip: The arthroscopic management of type 2 lesions in older patients can be biceps tenodesis, but young and active patients like throwers will need and arthroscopic repair.

INTRODUCTION

The long head of the biceps tendon and superior labrum help to stabilize the humeral head usually in the abducted and externally rotated arm. Injuries to the glenoid labrum represent a significant cause of shoulder pain especially among athletes involved in repetitive overhead activities[1]. After the development of shoulder arthroscopic interventions superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears are well recognized in recent times[2]. The name “SLAP” was used by Snyder et al[3] for the first time in the literature. These lesions occur either an isolated or in a conjunction with other shoulder problems like rotator cuff tears, instability or other biceps tendon pathologies[4,5]. There are different types of treatment modalities in different type of SLAP lesions. The treatment plan changes not only about the type of the lesion but also the age and functional level of the patient. Different treatment modalities were discussed in the literature. Our primary objective for this study was to help surgeons to better understand the pathology and make a decision for surgical management of SLAP tears according to type of the tear and patient’s characteristics.

ANATOMY

In order to understand the mechanism of this event it is best to understand the anatomic features around the glenoid. The glenohumeral joint is surrounded by a fibrocartilage tissue called labrum[6,7]. It increases the depth of glenoid fossa limiting the translation of humeral head and stabilizes the long head of biceps tendon improving glenohumeral joint stability[1]. Glenohumeral joint is stabilized by static and dynamic restraints. Static restraints include capsuloligamentous structures, labrum and negative intraarticular pressure. Dynamic restraints include rotator cuff muscles, periscapular muscles and biceps muscle[8]. The vascular supply of labrum is provided by suprascapular, circumflex scapular and posterior humeral arteries[6]. The anterosuperior margin of the glenoid rim has limited vascularity making it more vulnerable to injuries and having impaired healing potential[6]. The relationship between superior labrum and long head of biceps tendon is a special concern because of the considerable anatomic variability between this structures[8]. There are some anatomic variants for glenoid labrum and biceps tendon; the most common normal variation is a labrum attached to the glenoid rim and there is a broad middle glenohumeral ligament. One kind of anatomic variation is the sublabral recess, which represents a gap located inferior to the biceps anchor and the anterosuperior portion of the labrum. It is usually seen in 12-o’clock position of the glenoid in arthroscopic surgery[1]. Another variant is the sublabral foramen, which is a groove between the normal anterosuperior labrum and the anterior cartilaginous border of the glenoid rim. Another variation is the Buford complex which is characterized by the absence of the anterosuperior labral tissue with the presence of a thick cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament[1,8].

HISTORY AND CLASSIFICATION

Since the mid-1980s SLAP lesions were recognized as a cause of shoulder pain[9]. Kim et al[10] were the first authors who described that superior glenoid labrum tears are related to the long head of the biceps. After that Snyder et al. made the first classification system and established the current understanding of the pathologic anatomy of SLAP lesions[9]. They emphasized the concept that some of these lesions require repair rather than debridement[11]. Knesek et al[1] classified these tears into 4 distinct types (Figure 1).

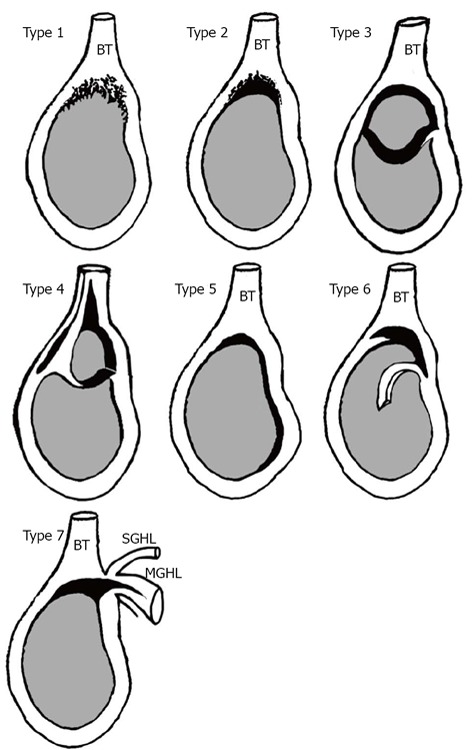

Figure 1.

Superior labrum anterior to posterior tear classification. Type 1: Degenerative fraying of the superior labrum, biceps anchor is intact; Type 2: Superior labrum and biceps tendon detachment from glenoid rim; Type 3: Bucket-handle tear of labrum with intact biceps anchor; Type 4: Bucket-handle tear of labrum extended into the biceps tendon; Type 5: Superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) with anterior inferior extension; Type 6: Anterior or posterior flap tear with the bucket handle component tear; and Type 7: SLAP with extension to the middle glenohumeral ligament.

Type 1 lesions are characterized by fraying and degeneration of the free edge of the superior labrum with intact biceps anchor; there is no any other concomitant shoulder pathology[12]. In type 2 lesions the labral degeneration is similar to type 1 lesions however there is detachment of the biceps anchor from the superior glenoid tubercle which leads to displacement of the biceps-superior labrum complex into the glenohumeral joint. Type 2 lesions are the most common subtype involving 41% of those shoulders identified in Snyder et al.’s original series[1]. The finding in type 3 lesions is the bucket handle tear of the superior labrum like meniscus in the knee joint. The biceps anchor in type 3 lesions is intact. Type 4 lesions involve the same bucket handle tear of the superior labrum but this tear extends into the biceps tendon root[13].

This classification system later required some modifications. According to Maffet et al[5] only 62% of their shoulder series was fitting to the Snyder’s classification schema. So they composed a new classification system. As a result they described 6 new subtypes; Type 5 lesions are characterized by a Bankart lesion that extends to the superior labrum and biceps anchor. In type 6 lesions there is an unstable labral flap with biceps tendon separation. If this separation of the biceps tendon-labral complex extends to the middle glenohumeral ligament, the lesion is called type 7[5]. Type 8 tears are same as type 2 tears with a posterior labral extension to the 6 o’clock position[14]. Type 9 lesions are more severe labral tears with circumferential involvement whereas type 10 lesions involve superior labral tear combined with a posteroinferior labral tear (reverse Bankart lesion)[14].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

SLAP tears have been recognized as a common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction in a specialized patient population namely athletes taking part in overhead activities and heavy duty workers[15,16]. Several potential mechanisms for the pathophysiology of superior labral tears in overhead athletes have been proposed[17]. With the hyperabduction and external rotation during throwing, there is an increase of shear and compressive forces on the glenohumeral joint and strain on the rotator cuff and capsulolabral structures[18]. Kinematic chain is a concept that refers to a combination of successively arranged rigid parts connected by joints. An example is the simple chain. When a force applies to the proximal part of the chain it will transfer to distal part through the joints. In a thrower, large forces and high amounts of energy are transfered from the legs, back and trunk to the arm and hand. The shoulder acts as a funnel and force regulator; and the arm acts as the force delivery mechanism. Uncontrolled throwing with relative imbalance of shoulder muscles, especially during the late cocking phase, may contribute to anterior glenohumeral instability and play a role in the development of SLAP tears[19,20]. Today it is known that glenohumeral external rotation increases by time, but this change might be accompanied by a loss of internal rotation capacity[16]. This internal rotation deficit is caused by contracture of the posteroinferior capsule that initiates the cascade of events ultimately resulting in tendinous and labral lesions[16]. This tight posteroinferior capsule shifts the glenohumeral contact point posterosuperiorly especially during overhead-throwing activitiy. This creates an internal impingement of the articular side of the rotator cuff tendons and posterosuperior labrum between the humerus and the glenoid rim, precipitating a SLAP lesion[1]. This internal impingement was first described by Walch et al[21] as an intraarticular impingement of the rotator cuff in the abducted and externally rotated shoulder. With 90 degrees of both abduction and external rotation, the articular surface of the posterosuperior rotator cuff becomes pinched between the labrum and the greater tuberosity.

There is also another causative factor for the superior labral tear called “peel-back” mechanism[13]. The twisting at the base of the biceps transmits torsional forces to the posterosuperior labrum, resulting in peel-back of the labrum[1]. This mechanism usually happens in a position of abduction and maximal external rotation, the rotation produces a twist at the base of the biceps tendon insertion which transmits torsional force to the area[13]. In a throwing shoulder, repeated initiation of this mechanism can lead to failure of the labrum over time with avulsion from the bone[22]. This happens usually during the deceleration phase of the arm[23].

The result of these events is a SLAP tear and possible rotator cuff tear. It should be kept in mind that scapula plays an important role in shoulder kinematics and altered scapular mechanics might also contribute to patient’s pain and shoulder dysfunction[19]. When the scapula does not perform its action properly, its malposition decreases normal shoulder function a condition called “scapulothoracic dyskinesis”. This condition causes visible alterations in scapular position and motion patterns. It is believed that it occurs as a result of changes in activation of the scapular stabilizing muscles; damage to the long thoracic,dorsal scapular or spinal accessory nerves or possibly reduced pectoralis minor muscle length may be the reason of this condition[24]. Visual findings of this dyskinesis are winging or asymmetry. It is observed during coupled scapulohumeral motions. This pathology should always be kept in mind for most of the shoulder disorders.Treatment of scapular dyskinesis is directed as managing underlying causes and restoring normal scapular muscle activation patterns by kinetic chain-based rehabilitation protocols[25].

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The clinical diagnosis of a SLAP lesion is an extremely challenging procedure because there are no unique clinical findings associated with this type of pathology. Also the condition is frequently associated with other shoulder problems such as impingement, rotator cuff tears, degenerative joint disease and other soft tissue-related injuries[14]. Before the physical examination, a proper patient history should be documented. There are often mechanical symptoms like clicking or popping especially during the cocking phase of throwing[1,6]. Concomitant lesions such as impingement, cuff tears or biceps tendinopathy might cause complaints like night pain, weakness and instability[1,5]. Physical examination starts with careful assessment of glenohumeral and scapulothoracic range of motion[1]. As previously mentioned, the external rotation capacity of the shoulder might even increase whereas the internal rotation capacity decreases as seen in overhead throwing athletes. This condition called glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD), should be measured if present with the patient lying supine on examination table and the shoulder is positioned at 90 degrees abduction with the elbow flexion respectively while the scapula is stabilized to eliminate any scapulothoracic motion. Any side-to-side difference in glenohumeral motion is then assessed by internally and externally rotating the arm[1].

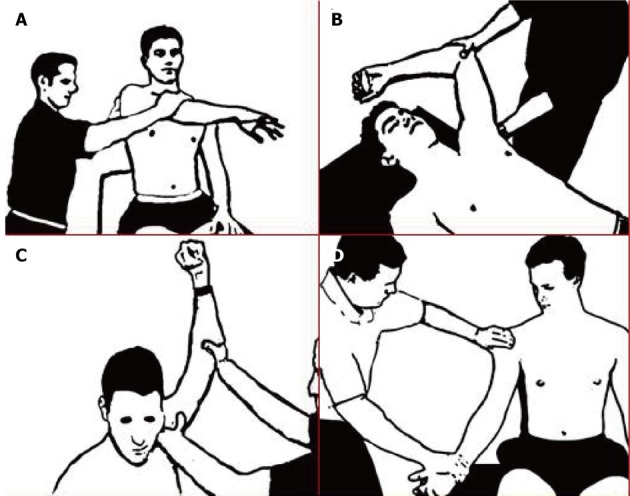

There are numerous physical examination tests described to detect a SLAP injury. They are usually sensitive but not specific[1]. These include Active Compression / O’Briens’s Test (Figure 2A), Biceps Load Test II (Figure 2B), O’Driscoll’s Dynamic Labral Shear Test (Figure 2C), Speed’s Test (Figure 2D) and Labral Tension Test[14]. Of these tests, only Biceps Load Test II shows utility in identifying patients with a SLAP-only lesion with no other concomitant pathology[26,27], however there are no convincing data either of these clinical tests is superior for accurate detection of a SLAP lesion (Table 1)[1,27,28] . Bennett reported a specifity of 14%, sensitivity of 90%, positive predictive value of 83% based on correlations of a positive Speed’s test with arthroscopic findings of biceps pathology[28,29].

Figure 2.

Physical examination tests described to detect a superior labrum anterior to posterior injury. A: O’Briens’s test. When the patient sitting with 90° of shoulder flexion and 10° of horizontal adduction, completely internally rotates the shoulder and pronates at the elbow. The physician applies downward force at the wrist or elbow and the patient resist the force. Pain on top of or inside the shoulder is considered a positive test; B: Biceps Load test. The patient supinates the arm, abduct the shoulder to 120 degrees, flex elbow to 90 degrees, externally rotate arm until the patient becomes apprehensive and provide resistance against elbow flexion, pain considered a positive test; C: O’Driscoll’s Dynamic Labral Shear test. When the the patient is standing with the arm laterally rotated at 120 degrees abduction, the examiner applies anterior shear force. A positive test is indicated by pain; D: Speed’s test. The patient's elbow is extended, forearm supinated and the arm elevated to 90°. The examiner resists shoulder forward flexion. Pain in the bicipital groove is considered a positive test.

Table 1.

Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination tests

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV/NPV |

| Biceps load test | 55 | 53 | 67/41 |

| O’Brien’s test | 91 | 14 | 66/44 |

| Speed’s test | 48 | 55 | 65/38 |

| O’Driscoll’s test | 89 | 30 | 69/60 |

| Labral tension test | 28 | 76 | 67/39 |

NPV: Negative predictive value; PPV: Positive predictive value.

Another important part of the physical examination is evaluation of scapular kinematics. There might be scapular dyskinesis which is described as altered scapular position and motion relative to the thoracic cage[1,23]. If a periscapular muscle atrophy or scapular winging is noted an associating cervical spine pathology should always be kept in mind[1].

IMAGING

Like any other musculoskeletal disease the painful shoulder evaluation begins with plain radiographs. This includes anteroposterior, outlet and axillary views. SLAP lesions have no specific findings in routine radiographs but coexisting pathologies such as outlet impingement, subluxation of glenohumeral joint and acromioclavicular abnormalities may be detected[1]. Currently MRI, particularly MR artrography (MRA) is the gold standard imaging method to detect SLAP tears[30,31]. Some physicians prefer computed tomography arthrography (CTA) to MRA as it is a cost effective method of imaging for labral pathologies[32]. In some studies the sensitivity and specificity were comparable in both MRA and CTA for labral lesions[32], but many studies showed that the sensitivity and specificity of CTA is lower than of the MRA, so in our opinion choosing CTA rather than MRA is a matter of physicians preference and availability of the imaging technique. As the indications and operative procedures varies in different types of SLAP lesions, pre-operative MR imaging is essential to detect detailed description of lesions. While sensitivity of MRI to detect SLAP tears is about 50%, in several studies sensitivity of MR arthrography is reported near 90%[1,30,31]. MR arthrography is the superior imaging technic and this superiority is because of the fact that the intra-articular injected contrast medium distends the joint capsule, outlines intra-articular structures and leaks into tears[30,31]. It means more clear delineation of the anatomic structures and SLAP lesions from anatomic variations like sublabral recess or sublabral foramen[1]. Sublabral recess or superior sulcus is a normal variant that is present in more than 70% of individuals. In this variation the base of superior labrum is not attached to the superior glenoid and in some cases this recess can be up to 1.4 centimeters deep[28]. MR artrography can also detect spinoglenoid cysts. These cysts may cause entrapment of suprascapular nerve causing shoulder pain, weakness in external rotation and infraspinatus muscle atrophy. Though MRA sensitivity is high, in several studies high incidence of false positive are reported[30,33,34]. SLAP tears are best seen on coronal oblique sequences in the ABER position as the contrast medium fills the gap between glenoid and superior labrum[33]. As mentioned before MR arthrography is the best imaging technic to evaluate the SLAP lesions but because of high incidence of false positive cases a detailed correlation with clinical history and physical examination is the key to diagnosis.

TREATMENT

The first step for the treatment of a suspected superior labral lesion should be a period of conservative treatment[35]. This includes rest, physical therapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Physical therapy seems only successful in few patients, mainly in type I SLAP lesions, it is only implemented in patients with this type of lesion or patients who do not wish to undergo surgery. Exercises to improve strength and endurance are not initiated until the pain is resolved[1]. Edwards et al[36] showed that successful non-operative treatment of superior labral tears results in pain relief and functional improvement compared with pre-treatment assessments. They found that return to sports was successful but return to overhead throwing sports at the same level was not possible. The goals of rehabilitation should include regaining the scapula and rotator cuff muscles strength and normal range of motion. Proprioception and neuromuscular control should be improved[1]. Besides the rehabilitation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and massage therapy can be used[37]. In case of conservative treatment failure, surgical procedures can be planned according to clinical history, examination and radiological findings for the patients doing sports, particularly overhead throwing athletes[38,39]. Repair, tenodesis, debridement, tenotomy, and observation have been recommended depending on the characteristics of the disease. Zhang et al. searched the database in United States between 2004 to 2009 with 25574 arthroscopic SLAP repairs. They found that there is a significant increase in repair number by time. The highest incidence of repair is in the 20-29 years and 40-49 years of age groups. Also there is a significant gender difference with men having three times higher incidence of repair[40].

Type 1 lesions which represents degenerative fraying without compromise of the labral attachment to the glenoid are treated with debridement only and rarely considered a source of clinical symptoms[12]. Simply arthroscopic shaving without damaging biceps anchor is enough for the surgical treatment of these type of lesions. Among various types of SLAP lesions, type 2 lesions are the most common form seen in clinical practice with visible detachment of the biceps anchor from the supraglenoid tubercle[2,41,42]. With the advancement of arthroscopic techniques, surgical treatment has evolved from isolated arthroscopic debridement to surgical repair of the lesion. These types of lesions can be treated with arthroscopic fixation of the superior labrum to establish biceps anchor stability. The initial studies suggested an extremely high level of success in arthroscopic repairs[35,43]. Morgan et al[13] published a retrospective review of 102 patients who underwent arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP tears. They reported 97% good or excellent results. However, the clinical results of elite throwing athletes has shown that this is not, in fact, always the case[44]. In a prospective analysis of type 2 SLAP repairs in 179 patients, Provencher et al[3] found clinical and functional improvement in shoulder outcomes. However, a reliable return to the previous activity level is limited with 37% failure rate with a 28% revision rate. The patients older than 36 years were associated with high chance of failure[3]. Because of unsatisfactory results in older patients[3], Boileau et al[45] suggested biceps tenodesis in these patients. They found that tenodesis is superior to the repair of type 2 SLAP tears in older population. However in another study by Alpert et al[46], it is shown that type 2 SLAP repairs using suture anchors can yield good to excellent results in patients older and younger than age 40. Their findings show no difference between two age groups[46]. So there is a conflict at the literature about the repairs of the older patients.

Type 3 lesions are characterised by bucket-handle tears of superior labrum with intact biceps anchor. Usually, the symptoms are because of the mobile labral fragment. This fragment can easily be debrided by an arthroscopic shaver. There is no need to repair this type of injury[47]. After the resection of the free fragment, a pain free shoulder can be established. There are limited information in the literature about the types other than type 2 lesions.

There are different surgical repair options for SLAP tears. These are nonabsorbable, absorbable and knotless anchors. Metallic anchors have been used over time. However, some complications like articular surface damage, migration, artifact production in postoperative MRI were reported. Then bioabsorbable tacks and anchors were used[48]. Also tacks are used in different types. There are some bad results with persistent pain and disability following the use of polyglycolide lactic (PLLA) tacks[49]. Foreign body reaction, synovitis and chondral damage were also reported[50,51]. The newer versions of absorbable anchors are proven to have equal pull-out strength as metallic anchors, with reported lower complication rates[52,53]. Although there are low complication rates, a recent study by McCarty et al[54] reported high complication rates. In revision cases, they found papillary synovitis, chondral damage and giant cell reactions in most of the patients[54]. But, it should be kept in mind that this study was performed on the revision cases. Knotless anchors are another option with shorter operation time and no knot at the joint which may be a cause for irritation. There are good results with knotless anchors that are equal to results of using standard anchors[55]. Biomechanically, knotless anchors’ initial fixation strength was found similar to that of simple suture repairs and the repairs restore the anatomy without over constraining the shoulder[56].

Diagnosis of the SLAP tears is based on clinical history, a detailed physical examination and MRI. MR arthrography is the best imaging technic for evaluating SLAP lesions. Arthroscopic SLAP repairs remain the gold standard with increased complication rates[57]. The clinicians should carefully choose the surgical treatment options for older patients and overhead athletes. In the older patients and revision cases, the biceps tenodesis or tenotomy should be kept as another option for treatment. Overhead throwers and young active people with type 2 SLAP tears can benefit from an arthroscopic repair. To date repair with knotless anchor systems seems to be as strong as simple sutures with less irritation in the joint.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Ko SH, Scibek JS S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Knesek M, Skendzel JG, Dines JS, Altchek DW, Allen AA, Bedi A. Diagnosis and management of superior labral anterior posterior tears in throwing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:444–460. doi: 10.1177/0363546512466067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JY, Chung SW, Jeon SH, Lee JG, Oh KS. Clinical and radiological outcomes of type 2 superior labral anterior posterior repairs in elite overhead athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:1372–1379. doi: 10.1177/0363546513485361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:880–886. doi: 10.1177/0363546513477363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grauer JD, Paulos LE, Smutz WP. Biceps tendon and superior labral injuries. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:488–497. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(92)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maffet MW, Gartsman GM, Moseley B. Superior labrum-biceps tendon complex lesions of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:93–98. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, O’Brien SJ, Warren RF, DiCarlo E, Allen AA. Anatomy, histology, and vascularity of the glenoid labrum. An anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prodromos CC, Ferry JA, Schiller AL, Zarins B. Histological studies of the glenoid labrum from fetal life to old age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1344–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanatli U, Ozturk BY, Bolukbasi S. Anatomical variations of the anterosuperior labrum: prevalence and association with type II superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1199–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1538–1543. doi: 10.1177/0363546512447785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Lee IS, Kim SH, Woo CM, Chun YM. Arthroscopic repair of concomitant type II SLAP lesions in large to massive rotator cuff tears: comparison with biceps tenotomy. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2786–2793. doi: 10.1177/0363546512462678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomlinson RJ, Glousman RE. Arthroscopic debridement of glenoid labral tears in athletes. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:42–51. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam EK, Snyder SJ. The diagnosis and treatment of superior labrum, anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:798–810. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310052901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, Gillespie M. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:553–565. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell SE, Nord KD, Ryu RKN. The diagnosis, classification and treatment of SLAP lesions. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2004;12:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Solovyova O, Rizvi SH, Mostofi A, Arciero RA. Traumatic shoulder instability involving anterior, inferior, and posterior labral injury: a prospective clinical evaluation of arthroscopic repair of 270° labral tears. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1687–1696. doi: 10.1177/0363546511405449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Kleunen JP, Tucker SA, Field LD, Savoie FH. Return to high-level throwing after combination infraspinatus repair, SLAP repair, and release of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2536–2541. doi: 10.1177/0363546512459481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part III: The SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:641–661. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:404–420. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kibler WB. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:325–337. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260022801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glousman R, Jobe F, Tibone J, Moynes D, Antonelli D, Perry J. Dynamic electromyographic analysis of the throwing shoulder with glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell ST. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: An arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:238–245. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkhart SS, Morgan CD. The peel-back mechanism: its role in producing and extending posterior type II SLAP lesions and its effect on SLAP repair rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:637–640. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:233–239. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClure P, Tate AR, Kareha S, Irwin D, Zlupko E. A clinical method for identifying scapular dyskinesis, part 1: reliability. J Athl Train. 2009;44:160–164. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kibler WB, McMullen J. Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:142–151. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karlsson J. Physical examination tests are not valid for diagnosing SLAP tears: a review. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20:134–135. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000369406.54312.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook C, Beaty S, Kissenberth MJ, Siffri P, Pill SG, Hawkins RJ. Diagnostic accuracy of five orthopedic clinical tests for diagnosis of superior labrum anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennet WF. Specificity on the Speed’s test: Arthroscopic technique for evaluating the biceps tendon at the level of bicipital groove. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:789–796. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(98)70012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rockwood AC, Matsen FA, Wirth MA, Lippitt SB, Editors . The shoulder: Saunders-Elsevier. 2009. pp. 145–176. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jee WH, McCauley TR, Katz LD, Matheny JM, Ruwe PA, Daigneault JP. Superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesions of the glenoid labrum: reliability and accuracy of MR arthrography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2001;218:127–132. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja44127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandnani VP, Yeager TD, DeBerardino T, Christensen K, Gagliardi JA, Heitz DR, Baird DE, Hansen MF. Glenoid labral tears: prospective evaluation with MRI imaging, MR arthrography, and CT arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:1229–1235. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.6.8249731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.OH JH, Kim JY, Choi JA, Kim WS, Effectiveness of multidetector computed tomography arthrography for the diagnosis of shoulder pathology: Comparison with magnetic resonance imaging with arthroscopic correlation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bedi A, Allen AA. Superior labral lesions anterior to posterior-evaluation and arthroscopic management. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:607–630. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connor PM, Banks DM, Tyson AB, Coumas JS, D’Alessandro DF. Magnetic resonance imaging of the asymptomatic shoulder of overhead athletes: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:724–727. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310051501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samani JE, Marston SB, Buss DD. Arthroscopic stabilization of type II SLAP lesions using an absorbable tack. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:19–24. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.19652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards SL, Lee JA, Bell JE, Packer JD, Ahmad CS, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Blaine TA. Nonoperative treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior tears: improvements in pain, function, and quality of life. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1456–1461. doi: 10.1177/0363546510370937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun S, Kokmeyer D, Millett PJ. Shoulder injuries in the throwing athlete. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:966–978. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snyder SJ, Banas MP, Karzel RP. An analysis of 140 injuries to the superior glenoid labrum. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuman BJ, Boisvert CB, Reiter B, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Cohen SB. Results of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes: assessment of return to preinjury playing level and satisfaction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1883–1888. doi: 10.1177/0363546511412317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang AL, Kreulen C, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Demographic trends in arthroscopic SLAP repair in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1144–1147. doi: 10.1177/0363546512436944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology. Part II: evaluation and treatment of SLAP lesions in throwers. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:531–539. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:274–279. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(90)90056-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enad JG, Gaines RJ, White SM, Kurtz CA. Arthroscopic superior labrum anterior-posterior repair in military patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen SB, Sheridan S, Ciccotti MG. Return to sports for professional baseball players after surgery of the shoulder or elbow. Sports Health. 2011;3:105–111. doi: 10.1177/1941738110374625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:929–936. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alpert JM, Wuerz TH, O’Donnell TF, Carroll KM, Brucker NN, Gill TJ. The effect of age on the outcomes of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior and posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:2299–2303. doi: 10.1177/0363546510377741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higgins LD, Warner JJ. Superior labral lesions: anatomy, pathology, and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(390):73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ozbaydar M, Elhassan B, Warner JJ. The use of anchors in shoulder surgery: a shift from metallic to bioabsorbable anchors. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1124–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sassmannshausen G, Sukay M, Mair SD. Broken or dislodged poly-L-lactic acid bioabsorbable tacks in patients after SLAP lesion surgery. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freehill MQ, Harms DJ, Huber SM, Atlihan D, Buss DD. Poly-L-lactic acid tack synovitis after arthroscopic stabilization of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:643–647. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkerson JP, Zvijac JE, Uribe JW, Schürhoff MR, Green JB. Failure of polymerized lactic acid tacks in shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:117–121. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhawan A, Ghodadra N, Karas V, Salata MJ, Cole BJ. Complications of bioabsorbable suture anchors in the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1424–1430. doi: 10.1177/0363546511417573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein T, Mehling AP, Ulmer M, Reck C, Efe T, Hoffmann R, Jäger A, Welsch F. MRI graduation of osseous reaction and drill hole consolidation after arthroscopic Bankart repair with PLLA anchors and the clinical relevance. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:2163–2173. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCarty LP, Buss DD, Datta MW, Freehill MQ, Giveans MR. Complications observed following labral or rotator cuff repair with use of poly-L-lactic acid implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:507–511. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kocaoglu B, Guven O, Nalbantoglu U, Aydin N, Haklar U. No difference between knotless sutures and suture anchors in arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesions in collision athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:844–849. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uggen C, Wei A, Glousman RE, ElAttrache N, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Biomechanical comparison of knotless anchor repair versus simple suture repair for type II SLAP lesions. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCormick F, Bhatia S, Chalmers P, Gupta A, Verma N, Romeo AA. The management of type II superior labral anterior to posterior injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]