Abstract

Background:

The relatively safe nature and cost-effectiveness of herbal extracts have led to a resurgent interest in their utility as therapeutic agents. Therefore, this prospective, double-blind, randomly controlled clinical trial was designed to compare the antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of newly formulated mouthrinse containing tea tree oil (TTO), clove, and basil with those of commercially available essential oil (EO) mouthrinse.

Materials and Methods:

Forty patients were selected for a 21-day study period and randomly divided into two groups. The test group patients were given newly formulated herbal mouthrinse and the control group patients were given commercially available EO mouthrinse. The Plaque Index (PI), Gingival Index (GI), and Papillary Marginal Attachment (PMA) Index were recorded at baseline, 14 days, and 21 days. The microbial colony forming units (CFU) were assessed at baseline and 21 days.

Results:

Test group patients using herbal mouthrinse showed significant improvement in GI (0.16), PI (0.57), and PMA (0.02) scores. These improvements were comparable to those achieved with commercially available EO mouthrinse. However, the aerobic and anaerobic CFU of microbiota were reduced with the herbal mouthrinse (P = 0.0000).

Conclusion:

The newly formulated herbal mouthrinse and commercially available mouthrinse were beneficial clinically as antiplaque and antigingivitis agents. Newly formulated mouthrinses showed significant reduction in microbial CFU at 21 days. So, our findings support the regular use of herbal mouthrinse as an antiplaque, antigingivitis, and antimicrobial rinse for better efficacy.

Keywords: Antigingivitis, antiplaque, basil, mouthrinse, tea tree oil

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal diseases are multifactorial in nature and several risk and susceptibility factors have been proposed to explain the onset and progression of the diseases.[1] However, most periodontal researchers have proven that oral microorganisms are the primary etiologic agents causing destruction of the supporting periodontal tissues.[2] Bacteria in the subgingival area are organized in a complex microbial biofilm. These biofilms are extraordinarily persistent, difficult to maintain, and play a vital role in periodontal disease and its progression. Thus, elimination of these bacterial biofilms is the priority of periodontal therapy.

Non-surgical periodontal treatment remains the core component of successful periodontal therapy.[3] Self-performed oral hygiene along with professional maintenance is the most effective method of prevention and maintenance of periodontal diseases. However, in reality, the degree of motivation and dexterity required for an optimal oral hygiene level may be beyond the ability of the majority of patients.[4] Chemical plaque control has been found to augment mechanical plaque control procedures. Mouthrinses provide a method of depositing an active material for slow release in the mouth. This helps in maintaining an effective concentration of the material in the mouth over a considerable period of time following its use. There are many such active materials which are conventionally administered by mouthrinses, for example, anti-inflammatories, fluorides, desensitizers, deodorants, and antimicrobials. Commercial interest in mouthrinses has been intense due to their effectiveness in reducing halitosis, build-up in dental plaque, and the associated severity of gingivitis, in addition to disinfecting the tongue. From this perspective, the utilization of antimicrobial mouthrinses, as antiplaque agents, has been considered a useful adjunct to oral hygiene.

Since 1970s, chlorhexidine digluconate has been considered to be the most effective plaque inhibitor against which other antiplaque agents are measured. But there are side-effects associated with chlorhexidine, such as staining of teeth, altered taste sensation, and supragingival calculus formation in some patients when used over a long period. As a result, there is an increased interest in research for newer formulations. The relative safe nature of herbal extracts has led to their use in several fields of medicine.

Herbal extracts and plant essential oils (EO) have the potential to be used as therapeutic agents for chronic gingivitis and periodontitis conditions that have both bacterial and inflammatory components. These are useful as their long-term daily use has no adverse effects on the health of an individual. Also, these are more cost-effective and easily available as over-the-counter products. In lieu of this, extensive research is being carried out, successfully, for formulations of various herbal mouthrinses for their effective long-term use. Some of the several herbal extracts that have been assessed in dentistry are aloe vera,[5] neem (Azadirachta indica),[6] basil (Ocimum sanctum),[7] tea tree oil (TTO) (Melaleuca alternifolia),[8] curcumin (Curcuma longa),[9] clove,[10] garlic,[11] etc.

A study was conducted to assess the efficacy of a newly formulated mouthrinse containing TTO, clove, and basil for its antiplaque and antigingivitis properties. Additionally, the effect of the mouthrinse on the plaque microbial load was also evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and design

The study was a randomized, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group design clinical trial. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee. The trial was a single-center study conducted in the Department of Periodontics. A written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the initiation of the study. A total of 50 patients were included in the study based on the statistical formula. Male or female non-smokers aged between 18 and 35 years with a Plaque Index (PI; Silness and Loe, 1964)[12] and Gingival Index (GI; Loe and Silness, 1963)[13] score of >1.5 were included in the study. The subjects were randomly allocated to one of the two groups using a computer-generated number to receive one of the two mouthwashes. The patients were randomly assigned to one of the following two groups: The test group (n = 25) in which patients were given the formulated coded herbal mouthrinse and the control group (n = 25) in which the patients were given a coded commercially available EO mouthrinse. The study duration was 21 days. The subjects had a minimum of 20 teeth and did not have diabetes, hepatic or kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or any other systemic condition contraindicating participation in the study. Exclusion criteria included individuals who had received chronic treatment with any medication like steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics, or with a history of periodontal therapy in the last 6 months.

Preparation of mouthrinse

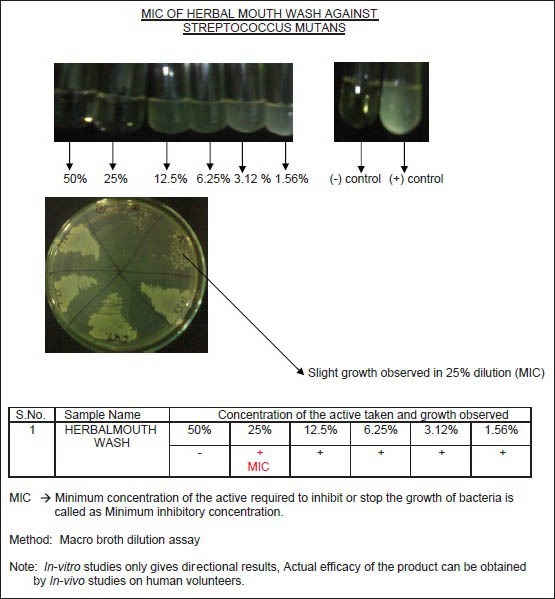

The active agents for the mouthrinse, namely TTO (0.2-0.3%), clove (0.2-0.3%), and basil (0.2-0.3%), were obtained from Suyash Herbs Exports Private Limited, Surat, Gujarat, India. The mouthrinse was formulated by Anchor Health and Beauty Care Pvt Ltd (Mumbai, India). A macro-broth dilution assay was performed to evaluate the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of the mouthrinse against the oral pathogen, Streptococcus mutans. The MIC was established to be 25% for the mouthrinse formulated [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration of herbal mouthrinse

Clinical procedure

All the subjects underwent oral prophylaxis procedure at the first visit. Patients were also given proper oral hygiene instructions including standard brushing technique with a toothpaste and toothbrush (provided to the patient), twice daily, during the study period. Patients were instructed to use the respective mouthrinse for 21 days (10 ml twice daily for 30 s). Patients were instructed not to drink, eat, or rinse for 30 min after the use of mouthrinse. The following indices were measured at baseline, 14 days, and 21 days: PI,[12] GI,[12] and Papillary Marginal Attachment (PMA) Index.[13] At each visit, each subject was also queried in a nonspecific manner to record any adverse events and the oral hygiene instruction was re-enforced.

Microbiological analysis

Plaque samples were collected at the baseline and at 21 days for microbiological evaluation. A sterile curette or a scaler was used to collect the plaque samples which were transported to the laboratory in thioglycollate broth for microbiological analysis. A quantitative analysis was conducted for the total aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. One loopful of sample was then inoculated onto blood agar supplemented with Hemin (5 μg/ml) and Vitamin K (10 μg/ml). Blood agar plates used for anaerobic isolation were prepared with Brucella agar base. Plates were incubated in anaerobic conditions for 3-5 days at 37°C. The anaerobiosis was carried out in the jar with “Internal Gas Generating system.” After 72 h of incubation at 37°C, the anaerobic jar was opened. The plates were examined for the presence of colonies. When the colonies appeared on the plates, the microorganisms were then identified under the microscope.

Data analyses

The mean and standard deviation were calculated for the clinical parameters (GI, PI, and PMA Index) and microbiological parameters [colony-forming units (CFU)/ml] of the test and control groups. Intra-group comparison was done using Student's paired t-test, while inter-group comparison was done using Student's unpaired t-test. The level of significance was 0.05. The MedCalc 10.2 software was used to perform the data analyses.

RESULTS

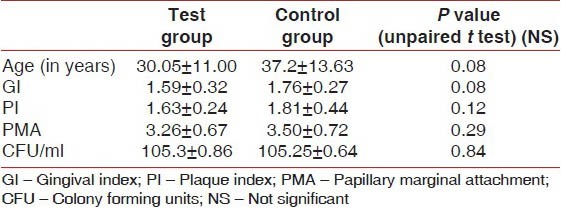

In the present 21-day follow-up study, out of the total 50 patients who participated in the study, 10 were dropouts (20%). Therefore, the analysis was carried out on 40 patients, 20 in each group. Demographic and baseline characteristics were similar across both the study groups [Table 1]. The average age of the test group was 30.05 ± 11.00 years and of the control group was 37.2 ± 13.63 years. The age difference between the two groups was statistically not significant. At Day 0 (baseline), the scores for GI, PI, and PMA Index, and the total microbial load (CFU/ml) were also comparable between the study groups. The differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05) [Table 1]. Thus, the similarities in patient selection enabled paired comparisons to be made between the two groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

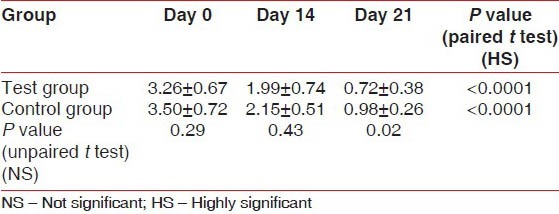

Clinical parameters

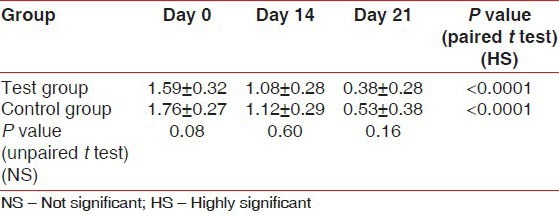

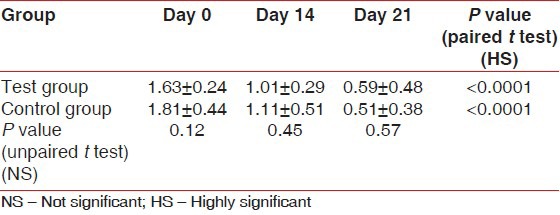

The scores for GI at Day 0 (baseline) were similar between the test group (1.59 ± 0.32) and the control group (1.76 ± 0.27). The differences were not significant statistically (P = 0.08). There was a highly significant (P < 0.0001) reduction in the GI scores from the baseline in the test group (1.08 ± 0.28 and 0.38 ± 0.28) and the control group (1.12 ± 0.29 and 0.53 ± 0.38) on Day 14 and Day 21, respectively. In comparison, the GI scores between the test and control groups on Day 14 (P = 0.60) and Day 21 (P = 0.16) were not statistically significant [Table 2]. The scores for PI at Day 0 (baseline) were similar between the test group (1.63 ± 0.24) and the control group (1.81 ± 0.44) with P = 0.12. On Day 14 and Day 21, the test group showed a reduction in the PI scores (1.01 ± 0.29 and 0.59 ± 0.48, respectively) from the baseline, while in the control group, the reduction in PI scores from the baseline were 1.11 ± 0.51 and 0.51 ± 0.38, respectively. The results were statistically highly significant (P < 0.0001). In comparison, the PI scores at Day 21 between the test group (0.59 ± 0.48) and the control group (0.51 ± 0.38) were statistically not significant (P = 0.57) [Table 3]. The scores for PMA Index at Day 0 (baseline) were similar between the test group (3.26 ± 0.67) and the control group (3.50 ± 0.72). The differences were not significant statistically (P = 0.29). Highly significant reduction in the scores from the baseline was seen in the test group (1.99 ± 0.74 and 0.72 ± 0.38) and the control group (2.15 ± 0.51 and 0.98 ± 0.26) on Day 14 and Day 21, respectively.

Table 2.

Gingival index

Table 3.

Plaque index

Within the groups, statistical significance was observed for GI, PI, and PMA index from the baseline to 21 days, indicating anti-inflammatory and antibacterial property of both mouthrinses. However, on comparing between the groups, the differences were not statistically significant [Table 4].

Table 4.

Papillary marginal attachment index

Microbiological parameters

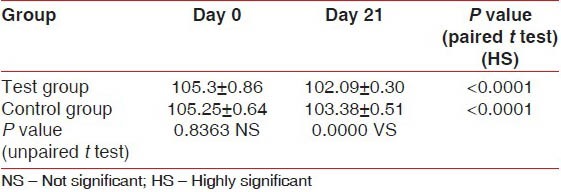

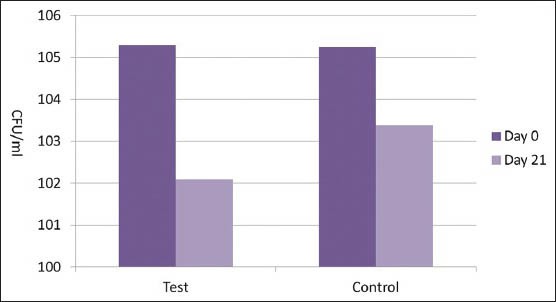

At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in the total microbial load (CFU/ml) between the test group (105.3 ± 0.86/ml) and the control group (105.25 ± 0.64/ml). In both the groups, there was a highly significant reduction in the total microbial load (CFU/ml) on Day 21 (102.09 ± 0.30/ml and 103.38 ± 0.51/ml, respectively). However, on Day 21, the microbial load in the test group was slightly lesser than in the control group. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 5 and Figure 2].

Table 5.

CFU/ml

Figure 2.

Colony forming units/ml

DISCUSSION

Herbal medications are being introduced for the prevention and treatment of oral conditions to enable their widespread use among all communities and are beneficial especially to those of low socioeconomic status. The cost-effectiveness of these products, along with the non-significant side-effects, guarantees a safe option to the current load of medications available. The study attempted to demonstrate the antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of a newly formulated herbal mouthrinse compared to the commercially available EO mouthrinse over a 21-day period. Findings in this study showed that the test group and control group had decreased PI, GI, and PMA scores, which can be attributed to the mouthrinses along with oral hygiene practices. No adverse effects were reported from subjects of both groups.

The control group (EO mouthrinse) also presented with reduction in GI, PI, and PMA scores. EO mouthrinse contains thymol and eucalyptol, mixed with menthol and methyl salicylate in a hydroalcoholic vehicle. The mechanisms of action of EO against bacteria are complex. The microbiological studies showed that EO killed a wide range of microorganisms within 30 s.[14] It penetrates the plaque biofilm and exerts a bactericidal activity to the embedded bacteria.[15,16,17] It kills microorganisms by disrupting their cell walls and inhibiting their enzyme activity.[18,19] Bacteria are prevented from aggregating with Gram-positive bacteria, and bacterial multiplication is slowed.[19] As a result, the bacterial load is reduced with slower plaque maturation and a decrease in plaque mass and pathogenicity. The above mechanism of action of EO is also suggested in the present study with the reduction of the scores [Tables 2–5].

In the present study, the efficacy of the herbal mouthrinse was highly significant in reducing the PI, GI, and PMA Index scores over the 21-day study period. The newly formulated mouthrinse contained a new combination of phytochemicals, namely TTO, clove, and basil. TTO (M. alternifolia) shares a similar range of antimicrobial activity with chlorhexidine, having antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties.[7] Clove oil is known for its analgesic, local anesthetic, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial effects.[10] Scientific studies have established that compounds in basil oil (O. sanctum) have potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties.[20] Both the groups showed antiplaque and anti-inflammatory property. In comparison, the scores of GI, PI, and PMA were non-significant and similar to each other. This indicates the similar effects of both the mouthrinses on the clinical parameters, with the added benefit of the alcohol-free formulation of mouthrinse in the test group. It has been observed that long-term use of alcohol-containing mouthrinses can cause desiccation of oral mucosal membranes, increase subjective xerostomia, and few cases of burning sensation of gingival tissues have also been reported.[21] However, the reduction in the microbial load with the test group mouthrinse was highly significant (P < 0.0001) than the reduction observed with the control group mouthrinse.

Saxer et al.[22] demonstrated that TTO (M. alternifolia) results in reduction in inflammation due to the presence of 1,8-cineole and terpinen-4-ol. TTO also results in less plaque formation as reported by Takarada et al.,[23] who demonstrated that TTO is able to inhibit the adhesion of S. mutans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Also, aqueous and methanol extracts of clove have been shown to inhibit adhesion of the bacteria to glass, reduce cell surface hydrophobicity, and inhibit the production of glucosyltransferase.[24] These properties of TTO and clove could account for the antiplaque and antigingivitis activities of the formulated mouthrinse.

TTO is efficacious against oral bacteria, with antiseptic, fungicidal, and bactericidal effects due to its active ingredients.[22] The other ingredient, clove oil, has been proven to have marked germicidal effect against various periodontal pathogens (Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella melaninogenica, P. gingivalis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga gingivalis, and Fusobacterium nucleatum) and superinfectants (Candida albicans, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli).[10] The clove buds suppress the oral microorganisms to 70% and it is evident from the fact that many toothpastes contain clove oil as their major constituent. Basil (O. sanctum) was reported to possess antibacterial properties by Mondal et al.[25] These properties are due to the high percentage of eugenol (61.2%) and monoterpene components, mostly phenolic in nature, like methyl eugenol (1.8%) and carvacrol (30.4%), which exert membrane-damaging effects to microbial strains and stimulate leakage of cellular potassium ions which are responsible for a lethal action related to cytoplasmic membrane damage.[25] Basil extracts decrease plasma malondialdehyde (MDA) and increase serum superoxide dismutase (SOD), resulting in an antioxidant effect.[26] Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been proven to have a definite role in the progression of periodontal diseases.[27] However, this role of basil extracts has been proven in various animal models for peptic ulcers, with inconclusive evidence against oral pathogens.[26] Thus, the combined antibacterial effect of the three ingredients could have led to a superior reduction in the microbial load of the herbal mouthrinse as compared to the commercial one.

CONCLUSION

Thus, the positive results of the present study suggest that the newly formulated mouthrinse containing TTO, clove, and basil demonstrates antiplaque, antigingivitis, and antibacterial properties, which may be useful as an adjunctive to mechanical therapy in the prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases. It has the potential of becoming a commercial commodity by virtue of the harmonious properties of the individual ingredients. But additional long-term longitudinal trials are required to further assess the efficacy of the mouthrinse to be utilized as an adjuvant to periodontal therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are thankful to Mr. M. D. Mallapur, Statistician, Departement of Community Medicine, JNMC, Belgaum for statistical analysis and Dr. Amrita Rathore, Department of Periodontics, KLE VK Institute of Dental Sciences, Belgaum for her support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Kornman KS. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: An introduction. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:135–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobb CM. Non-surgical pocket therapy: Mechanical. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:443–90. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch G, Lindhe J. The effect of supervised oral hygiene on the gingiva of children. J Periodontal Res. 1967;2:64–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1967.tb01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutter JA, Salman M, Stavinoha WB, Satsangi N, Williams RF, Streeper RT, et al. Antiinflammatory C-glucosyl chromone from Aloe barbadensis. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:541–3. doi: 10.1021/np9601519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botelho MA, dos Santos RA, Martins JG, Carvalho CO, Paz MC, Azenha C, et al. Efficacy of a mouthrinse based on leaves of the neem tree (Azadirachta indica) in the treatment of patients with chronic gingivitis: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Med Plant Res. 2008;2:341–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal P, Nagesh L, Murlikrishnan Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of various concentrations of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) extract against Streptococcus mutans: An in vitro study. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:357–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.70800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soukoulis S, Hirsch R. The effects of a tea tree oil-containing gel on plaque and chronic gingivitis. Aust Dent J. 2004;49:78–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suhag A, Dixit J, Dhan P. Role of curcumin as a subgingival irrigant: A pilot study. PERIO: Periodontal Pract Today. 2007;4:115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali HS, Kamal M, Mohamed SB. In vitro clove oil activity against periodontopathic bacteria. J Sci Tech. 2009;10:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groppo FC, Ramacciato JC, Simões RP, Flório FM, Sartoratto A. Antimicrobial activity of garlic, tea tree oil, and chlorhexidine against oral microorganisms. Int Dent J. 2002;52:433–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loe H. The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Retention Index Systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38:610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schour I, Massler M. Gingival disease in postwar Italy (1945) prevalence of gingivitis in various age groups. J Am Dent Assoc. 1947;35:475–82. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1947.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross NM, Charles CH, Dills SS. Long-term effects of Listerine antiseptic on dental plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Dent. 1989;1:92–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine DH, Furgang D, Lieb R, Korik I, Vincent JW, Barnett ML. Effects of sublethal exposure to an antiseptic mouthrinse on representative plaque bacteria. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:444–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan P, Barnett ML, Coelho J, Brogdon C, Finnegan MB. Determination of the in situ bactericidal activity of an essential oil mouthrinse using a vital stain method. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:256–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapiro S, Giertsen E, Guggenheim B. An in vitro oral biofilm model for comparing the efficacy of antimicrobial mouthrinses. Caries Res. 2002;36:93–100. doi: 10.1159/000057866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubert D, Rubin M, Barnett ML, Vincent JW. Antiseptic mouthrinse-induced microbial cell surface alterations. Am J Dent. 1993;6:277–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouhayoun JP. Penetrating the plaque biofilm: Impact of essential oil mouthwash. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:10–2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.30.s5.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh S, Majumdar DK, Rehan HM. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory potential of fixed oil of Ocimum sanctum (Holy basil) and its possible mechanism of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;54:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)83992-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiken Albertsson K, Persson A, Lingstrom P, van Dijken JW. Effects of mouthrinses containing essentials oils and alcohol-free chlorhexidine on human plaque acidogenicity. Clin Oral Investig. 2010;14:107–12. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxer UP, Stäuble A, Szabo SH, Menghini G. Effect of mouthwashing with tea tree oil on plaque and inflammation. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2003;113:985–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takarada K, Kimizuka R, Takahashi N, Honna K, Okuda K, Kato T. A comparison of the antibacterial efficacies of essential oils against oral pathogens. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004;19:61–4. doi: 10.1046/j.0902-0055.2003.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahim ZH, Khan HB. Comparative studies on the effect of crude aqueous (CA) and solvent (CM) extracts of clove on the cariogenic properties of Streptococcus mutans. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:117–23. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mondal S, Bamola VD, Mirdha BR, Naik SN, Verma S, Padhi MM, et al. Effects of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn) on immune parameter of healthy volunteers. Journal of Pharmacy Pharmacology. 2010;62(10):1486–1487. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kath RK, Gupta RK. Antioxidant activity of hydroalcoholic leaf extract of Ocimum sanctum in animal models of peptic ulcer. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;50:391–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gustafsson A, Asman B. Increased release of free oxygen radicals from peripheral neutrophils in adult periodontitis after Fc delta-receptor stimulation. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:38–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]