Abstract

Background:

Owing to its stimulatory effect on angiogenesis and epithelialization, platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is an excellent material for enhancing wound healing. The use of PRF dressings may be a simple and effective method of reducing the morbidity associated with donor sites of autogenous free gingival grafts (FGGs). The purpose of this case series is to document the beneficial role of PRF in the healing of FGG donor sites.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 18 patients treated with FGGs could be classified into two groups. PRF was prepared, compressed and used to dress the palatal wound followed by a periodontal pack in one group (10 patients) and only a periodontal pack was used in the other group (8 patients). Post-operative healing was assessed clinically at 7, 14 and 21 days and the morbidity was assessed qualitatively by an interview.

Results:

Sites where PRF was used showed complete wound closure by 14 days and these patients reported lesser post-operative morbidity than patients in whom PRF was not used.

Conclusions:

PRF as a dressing is an effective method of enhancing the healing of the palatal donor site and consequently reducing the post-operative morbidity.

Keywords: Free gingival graft, healing, patient morbidity, platelet-rich fibrin, post-operative bleeding

INTRODUCTION

The keratinized gingiva of the hard palate is a common site to obtain a free soft-tissue graft for various periodontal plastic surgical procedures. Free soft-tissue grafts may be in the form of free gingival grafts (FGGs) or sub-epithelial connective tissue grafts. Palatal grafts owing to their thickness and autogenous nature yield excellent clinical results and are hence considered superior to synthetic or allogenic grafts.[1] Excessive post-operative morbidity has been reported in the literature as a possible complication of harvesting a FGG. This may be in the form of pain, hemorrhage or necrosis.[2]

Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin (PRF); is a second generation platelet concentrate.[3] It is said to have a stimulatory effect on wound healing due to the presence of many growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and epidermal growth factor.[4] It also provides an excellent scaffold for angiogenesis and epithelialization.[4]

Reports on the role of PRF as an adjunct for wound healing in the oral cavity are scarce. This case series will provide insights on the clinically beneficial role of PRF in palatal wound healing and the consequent reduction in post-operative morbidity. An attempt has also been made to compare the palatal wound healing with sites where PRF was not used.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 18 systemically healthy patients treated for lack of attached gingiva using autogenous FGGs were evaluated for this case series. PRF had been used to cover the palatal FGG donor sites in 10 consecutively treated patients (5 males and 5 females). The mean age of the subjects was 42 years (Range: 16-56 years). A written, informed consent had been obtained from all the 18 treated patients.

The recipient bed preparation for the FGG was performed as the first step of the surgical procedure.

Donor site

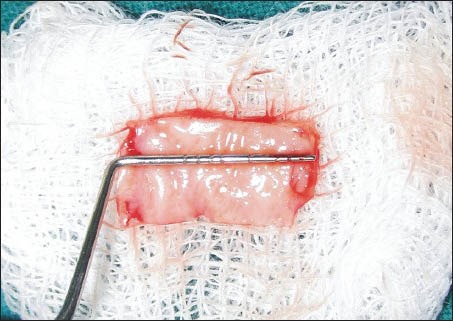

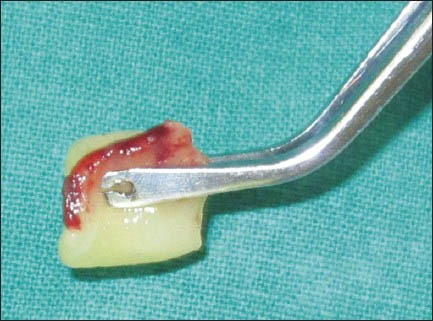

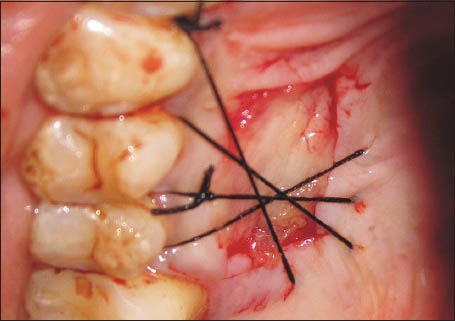

A 1.0 mm split-thickness gingival graft of the required length and breadth was obtained from the palatal keratinized gingiva adjacent to the premolars and the first molar using the conventional scalpel technique [Figure 1]. PRF was prepared using the method suggested by Dohan et al.[3] A sample of 10 ml venous blood was withdrawn from patient and transferred into a sterile test tube. The collected blood was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to obtain the PRF. The PRF was then squeezed gently between two pieces of gauze to form a membrane. This membrane was folded to the required thickness (1.0 mm) and accurately trimmed to match the palatal wound [Figure 2]. In 10 of the considered cases, the PRF membrane was then placed at the palatal donor site and compressed with gauze [Figure 3]. It was then secured with 3-0 black braided silk [Figure 4]. A non-eugenol pack was then placed over the donor site in all the eighteen cases.

Figure 1.

Free gingival graft harvested from the palate

Figure 2.

Platelet-rich fibrin membrane

Figure 3.

Platelet-rich fibrin membrane placed at the free gingival grafts donor site

Figure 4.

Platelet-rich fibrin membrane secured to the palate

Recipient site

The FGG was sutured at the prepared recipient bed using size 4-0 resorbable sutures (polyglactin 910). A non-eugenol pack was then placed over the secured FGG. Patients were prescribed 600 mg Ibuprofen, 3 times a day for 3 days and a 0.2% chlorhexidine oral rinse twice a day for 2 weeks. Patients were advised to report any adverse outcomes and were recalled after 7, 14 and 21 days.

Criteria and methodology to assess wound healing

At 7, 14 and 21 days, an examiner who was blinded to the treatment group, assessed the palatal healing by direct examination of the donor site. The criteria used for assessing wound healing included; the epithelialization (as assessed clinically by looking for wound closure),[5] the degree of inflammation in the tissue peripheral to the donor site and the appearance of the margins of the wound. The post-operative morbidity was assessed by asking patients to rate the post-operative pain on a Wong and Baker Faces Scale (WBFS).[6]

RESULTS

PRF series

Patients reported back with a dislodged palatal pack on the 3rd or 4th day after surgery. On examination of the palatal wound, it was observed that the sutures were intact and the PRF was adherent to the palatal wound. On day 7, as per the scheduled recall, the palatal sutures were removed. On the 7th day, the donor site showed a good amount of wound closure. The tissue surrounding the healing donor site showed no inflammation and the margins of the wound were seen to be gaining a normal appearance [Figure 5]. The donor site wound was also observed to be smaller in size than the dimensions of the obtained graft. Complete wound closure was seen at 14 days [Figure 6].

Figure 5.

Donor site at 1 week post-operatively

Figure 6.

Donor site at 2 weeks post-operatively

Non-PRF series

On the 7th day, the donor sites in this series still retained a raw appearance. The sites failed to show wound closure and retained a layer of slough on the surface [Figure 7]. Figure 8 shows the 14 day healing of a site where PRF was not used. On the 14th day, incomplete wound closure of the donor site and some inflammation in the adjacent areas was noted on clinical examination.

Figure 7.

Healing of a site where platelet-rich fibrin was not used at 1 week post-operatively

Figure 8.

Healing of a site where platelet-rich fibrin was not used at 2 weeks post-operatively

Post-operative interview

At the 7 day recall visit, all the patients were asked to rate the post-operative discomfort and pain on a WBFS of 0-10. The value “0” represented “no pain or discomfort” and the value “10” represented “worst possible pain”.[6] Patients in whom PRF was used to dress the palatal wound were seen to be relatively comfortable during the 1st week post-operatively as evidenced by the mean score of 3.3 ± 1.42. The lowest WBS score in the PRF group was 1 and the highest score was 6. In the non-PRF group, a mean score of 4.625 ± 1.06 was observed. The lowest score in this group was 3 and the highest score was 6.

DISCUSSION

Long-term evaluation of the FGG for augmentation of attached gingiva has shown maintainable results up to a period of 25 years.[7] Thus, the palatal FGG remains to this day, the most reliable gingival grafting material for augmentation of keratinized gingiva. However, post-operative considerations such as persistent bleeding, pain and discomfort at the palatal donor site are the reasons for the FGG procedure not being a very popular choice among clinicians in spite of the superior clinical results.

Studies have reported that more pain and morbidity is associated with a FGG technique wherein the palatal donor site heals by secondary intention.[1,8,9] The use of a PRF membrane to cover the fresh wound may hasten the process of wound healing by providing a stable fibrin mesh, which is more rigid than a blood clot[4] and by providing a sustained release of growth factors.[10] Apart from these properties, the ability of PRF to arrest bleeding was also noted in our cases. It was observed that placement of PRF at the FGG donor site led to rapid hemostasis.

A study done by Choukroun et al.,[4] stated that the fibrin present in the PRF guides the initial angiogenesis modulated by the binding to various growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor-basic, PDGF, vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin. The authors also mentioned a role of fibrin in modulating neutrophil activity and in inducing epithelial cell migration to augment the process of wound healing. The excellent healing response that was observed in our cases [Figure 6] provides credence to the notion that the PRF catalyzes healing not only by releasing growth factors, but also by providing a stable fibrin scaffold and by causing hemostasis. This justifies the term “healing biomaterial” attributed to it.[4]

Patients from both groups reported that the periodontal pack used to cover the palatal site was dislodged by 3-4 days post-operatively following which they were examined and reassured. Patients when examined after dislodgement of the periodontal pack in the PRF series showed that the PRF was still adherent to the palatal wound. All the 10 patients who were treated using PRF to cover the palatal donor site reported being relatively free of discomfort after the surgery. On the other hand, patients in whom PRF had not been used complained of discomfort at the palatal site. The notable features in the group of patients treated using PRF were; almost complete closure of the wound at 1 week, lack of inflammation at the periphery of the healing wound and good control of bleeding at the time of the surgery. Silva et al.[5] observed that most (92%) patients showed complete epithelization and closure of the palatal FGG donor site at 15 days post-operatively. Del Pizzo et al.[8] reported that only 17% of their patients (non-smokers) showed complete epithelialization of the palatal FGG donor site after 15 days of graft harvesting. Patients treated using PRF in the present case series showed a faster healing of the donor site as seen by almost complete wound closure at 7 days and complete wound closure and epithelialization at 14 days post-operatively.

Tomlinson et al. in a recent systematic review have concluded that the WBFS is a reliable and easy to use pain rating scale.[11] The authors have also mentioned that this scale has adequate psychometric properties and is acceptable to all age groups.[11] Based on these observations it may be assumed that the WBFS is a suitable tool to assess post-operative pain. The lower mean scores on the WBFS observed in the group treated using PRF may not be statistically conclusive of a benefit, but indicate that these patients did experience less pain and thus were more comfortable in the healing period.

As all the patients consumed analgesics for 5 days after the surgery, an association between analgesic ingestion and use of PRF could not be evaluated. Furthermore, as the pain associated with the recipient site was an inherent factor, the analgesic regimen could not be deferred in order to validate the hypothesis that the use of PRF reduces the post-operative pain.

The use of PRF to cover the palatal wound was started as an enquiry into its benefit based on reasonable evidence. As excellent result was observed in 10 consecutive cases, it was deemed essential to report the same in scientific literature. Well designed and controlled studies need to be carried out to provide further credence to these observations. The additional parameter of tissue thickness at the donor site may also be included to investigate if PRF provides additional bulk to the healed site.

CONCLUSIONS

A FGG is a tried and tested technique for augmentation of keratinized gingiva and recession coverage and is yet to be substituted by any other technique. The morbidity associated with the palatal donor site is one of the important factors discouraging the clinicians to routinely use this technique. PRF, if used as a “bio-active dressing”, can reduce the patient morbidity to a great extent and also hasten the healing of the donor site thus eliminating one of the major concerns associated with the use of this technique. This case series documents a novel technique to use Choukroun's PRF in augmenting palatal healing and in reducing the post-operative morbidity after harvesting a FGG. This fascinating biomaterial is a boon to the field of periodontal surgery and needs to be explored further.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cortellini P, Pini Prato G. Coronally advanced flap and combination therapy for root coverage. Clinical strategies based on scientific evidence and clinical experience. Periodontol 2000. 2012;59:158–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zucchelli G, Mele M, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C, Marzadori M, Montebugnoli L, et al. Patient morbidity and root coverage outcome after subepithelial connective tissue and de-epithelialized grafts: A comparative randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:728–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choukroun J, Diss A, Simonpieri A, Girard MO, Schoeffler C, Dohan SL, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part IV: Clinical effects on tissue healing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva CO, Ribeiro Edel P, Sallum AW, Tatakis DN. Free gingival grafts: Graft shrinkage and donor-site healing in smokers and non-smokers. J Periodontol. 2010;81:692–701. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agudio G, Nieri M, Rotundo R, Cortellini P, Pini Prato G. Free gingival grafts to increase keratinized tissue: A retrospective long-term evaluation (10 to 25 years) of outcomes. J Periodontol. 2008;79:587–94. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Pizzo M, Modica F, Bethaz N, Priotto P, Romagnoli R. The connective tissue graft: A comparative clinical evaluation of wound healing at the palatal donor site. A preliminary study. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:848–54. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffin TJ, Cheung WS, Zavras AI, Damoulis PD. Postoperative complications following gingival augmentation procedures. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2070–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, de Peppo GM, Doglioli P, Sammartino G. Slow release of growth factors and thrombospondin-1 in Choukroun›s platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A gold standard to achieve for all surgical platelet concentrates technologies. Growth Factors. 2009;27:63–9. doi: 10.1080/08977190802636713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomlinson D, von Baeyer CL, Stinson JN, Sung L. A systematic review of faces scales for the self-report of pain intensity in children. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1168–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]