Abstract

Lignin comprises 15.25% of plant biomass and represents a major environmental carbon source for utilization by soil microorganisms. Access to this energy resource requires the action of fungal and bacterial enzymes to break down the lignin polymer into a complex assortment of aromatic compounds that can be transported into the cells. To improve our understanding of the utilization of lignin by microorganisms, we characterized the molecular properties of solute binding proteins of ATP.binding cassette transporter proteins that interact with these compounds. A combination of functional screens and structural studies characterized the binding specificity of the solute binding proteins for aromatic compounds derived from lignin such as p-coumarate, 3-phenylpropionic acid and compounds with more complex ring substitutions. A ligand screen based on thermal stabilization identified several binding protein clusters that exhibit preferences based on the size or number of aromatic ring substituents. Multiple X-ray crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes for these clusters identified the molecular basis of the binding specificity for the lignin-derived aromatic compounds. The screens and structural data provide new functional assignments for these solute.binding proteins which can be used to infer their transport specificity. This knowledge of the functional roles and molecular binding specificity of these proteins will support the identification of the specific enzymes and regulatory proteins of peripheral pathways that funnel these compounds to central metabolic pathways and will improve the predictive power of sequence-based functional annotation methods for this family of proteins.

Keywords: ABC transporter, functional annotation, Rhodopseudomonas palustris, solute-binding protein, p.coumaric acid

INTRODUCTION

Lignin comprises 15.25% of plant biomass and contributes significantly to the reservoir of soil organic matter available to microorganisms. Increased knowledge of cellular mechanisms that influence the breakdown and use of this abundant polymer would improve our understanding of microbial community structure and their role in global carbon cycling. Lignin is produced in plants by a largely random polymerization of phenylpropanoid subunits which results in a chemically heterogeneous molecule that resists biological degradation1. However, some species of fungi, primarily white rot basidiomycetes, produce multiple classes of laccases and peroxidases2 that can partially or completely break down lignin by free radical oxidation of the polymer. Recent studies also indicate that bacterial consortia have a role in the degradation and utilization of lignin3-6. Some bacterial species show ligninolytic characteristics and to a limited extent are able to solubilize large fragments by cleaving them into small monomers.

In spite of the limited number of organisms that can degrade polymeric lignin, many species of bacteria from diverse phyla can utilize monomeric lignin degradation products as a carbon source in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions7-10. These bacteria employ a common metabolic strategy that transforms the complex assortment of degradation products into a limited number of aromatic compounds which then proceed through central degradation pathways that perform aromatic ring cleavage7,8,11. In a previous study12, we characterized several solute binding proteins (SBPs) that mediate the transport of benzoate.like compounds that feed directly into central degradation pathways. However, few proteins involved in the transport or metabolism of non.benzoate compounds such as p-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, or sinapic acid have been experimentally characterized. Relative to the benzoate.derived compounds, these phenylpropanoid compounds have more diverse biological roles which extend beyond their use as carbon sources. Recent studies have demonstrated these compounds have an emerging role in quorum sensing mechanisms that allow bacteria to alter metabolism based on population density in the surrounding environment to coordinate biological responses such as pathogenicity, sporulation, competence, and biofilm formation13,14. Multiple bacterial species utilize fatty.acid homoserine lactone (HSL) derivatives as a small molecule messenger for quorum sensing. Quorum sensing in Rhodopseudomonas palustris and Bradyrhizobium japonicum has recently been described; however these microbes use p-coumaryl.HSL or cinnamoyl-HSL as chemical messengers instead of fatty acids from intracellular pools. The bacteria have signal receptors that respond to p-coumaryl.HSL to regulate global gene expression. R. palustris uses an acyl-HSL synthase to produce p-coumaryl-HSL using environmentally-derived p-coumaric acid. Other bacteria including Bradyrhizobium sp. and Silicibacter pomeroyi also have the enzymatic capability for production of p-coumaroyl.HSL, indicating that utilization of phenylpropanoid-HSL messaging compounds may be a widespread communication strategy among Alphaproteobacter. Consequently, the extracellular presence and transport of phenylpropanoid compounds can impact cell behavior beyond metabolism of this small molecule as a carbon source. These discoveries extend the range of potential HSL. liganded molecules that may be utilized for quorum sensing and raises fundamental questions about quorum sensing within the context of environmental signaling.

To characterize the biological impact of phenylpropanoid products derived from lignin, we focused on profiling the binding specificity of SBPs of ATP.binding cassette (ABC) transporters as this activity is coordinated with cellular metabolic and regulatory capabilities. Functional characterization of the proteins that mediate transport of non-benzoate compounds would provide a mechanism to identify the specific enzymes and regulatory proteins of peripheral metabolic pathways that funnel these compounds to central metabolic pathways. Peripheral pathways typically transform aromatic compounds into catechol or 3,4- dihydroxybenzoic acid for aerobic metabolism, whereas most anaerobic pathways utilize benzoyl.coenzyme A (CoA) as the central intermediate7,8,11,15. During anaerobic growth on p- coumaric acid in R. palustris, the propenoic acid group is activated by the addition of a CoA. thioester moiety as the first step of a pathway that eventually results in production of benzoyl. CoA prior to ring cleavage and subsequent conversion into intermediate metabolites used for microbial growth. Few of the enzymes that mediate CoA activation have been characterized; of the 44 predicted CoA ligases and 27 enoyl.CoA hydratases in R. palustris CGA009 only four CoA ligases have been characterized16. The BadA ligase specifically activates benzoic acid17, HbaA and AliA activate 4-hydrozybenzoic acid18 and cyclohexanecarboxylate 19, respectively, while CouB activates several phenylpropanoid aromatic compounds including p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and caffeic acid16. As many of the transport proteins are co.localized with CoA ligases, profiling the transporter capabilities would provide preliminary guidance for selection of ligands in enzyme activity screens. Accurate identification of transported small molecules would also facilitate the identification of regulatory mechanisms as transported compounds or their metabolic products often mediate control of gene expression through direct interaction with transcriptional regulators. In R. palustris, the metabolism of p-coumaric acid is directly regulated by the binding of p-coumaryl-CoA to the CouR repressor16 while the binding of benzoyl-CoA to BadR20 regulates in part the enzymes required for the anaerobic degradation of benzoic acid.

Although research has begun to elucidate the metabolic mechanisms for use of small aromatic molecules, very few transporters for phenylpropanoid compounds have been experimentally characterized. There are two identified transporters which act on structurally similar molecules; HcaT, a Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) transporter identified in Escherichia coli21 and HppK, an MFS.type transporter from Rhodococcus globerulus PWD122. These transporters have predicted activity for hydrocinnamic acid and 3-hydroxyhydrocinnamic acid, respectively, but their complete ligand transport profiles have not been investigated. Other well.characterized MFS.type aromatic acid transporters have shown activity only with benzoate derivatives23,24.

Small molecules can also be imported from the environment using ATP-dependent transporters. ABC transporters are ubiquitous proteins utilized in all kingdoms of life to translocate molecules across cellular membranes. A typical gram-negative bacterial importer consists of a SBP, a permease, and an ATPase. The SBP is located in the periplasm and binds ligands and localizes them to the appropriate permease for transport. The SBP is highly selective and is the primary mechanism by which the transporter specificity is determined. The permease is embedded in the membrane and forms the channel through which a ligand is imported. The ATPase is located in the cytoplasm; small molecule transport is initiated only when the ATPase associates with the cytoplasmic domain of the permease and hydrolyzes ATP. ABC transporters facilitate the movement of a wide variety of molecules, including metal ions, amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, fatty acids, and iron.siderophore complexes25. This wide diversity of ligands complicates de novo prediction of biological function and ligand specificity when performing homology-based genome annotation. Furthermore, in organisms with novel metabolic capabilities it is difficult to assign transporter function based on genome context because co-localized enzymes are also uncharacterized.

In a previous study, we identified two SBPs from R. palustris (RPA1789 and RPA4648) that bound phenylpropanoid compounds26. Both of these proteins showed thermal stabilization with p-coumaric acid, indicating that they may mediate transport of this aromatic acid or structurally similar ligands. In this manuscript, we employ structural and functional characterization methods to determine the molecular basis for aromatic compound binding to these proteins and to other SBPs that mediate the import of phenylpropanoid compounds derived from lignin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Homolog identification

Potential homologs of previously characterized solute.binding proteins from R. palustris CGA009 were identified in other organisms by sequence alignments generated with the BLAST algorithm 27. Sequenced genomes from R. palustris strains HaA2 (RPB), BisB18 (RPC), BisB5 (RPD), BisA53 (RPE), B. japonicum USDA 110 (bll, blr), S. meliloti 1021 (SM_a, SM_b, SM_c) and N. winogradskyi Nb.255 (Nwi) were included in this analysis. Gene coding sequences were obtained from the NCBI microbial genome data repository.

Ligand library

Reagent-grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Ligands were dissolved in one of 3 buffers: standard HEPES buffer at pH 7.5 (100 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl), nonstandard HEPES buffer at pH 12.6, or 100% DMSO. Compatible solvents and ligand stock concentrations were determined by consultation of chemical reference sources and experimental evaluation of assay performance. Stocks were stored at 4°C and examined prior to each assay for evidence of precipitation or color change. None of the small aromatic molecules in this set produced background fluorescence in the screening assays due to ligand.dye interactions. Reactions containing gallic acid and 2,3,4. trihydroxybenzoic acid discolored during the thermal melt program. Although the discoloration did not prevent determination of melting temperatures, results obtained with these compounds were excluded from the analysis.

Fluorescence Thermal Shift (FTS) assay

The FTS screening method26,28 was used in a microwell plate format to identify binding ligands for the SBPs of ABC transporters. Although previous screening protocols used pooled ligands followed by deconvolution of the binding profile with individual ligands we anticipated binding events with multiple aromatic substances in this target set. Based on previous experience and well.supported sequence.based predictions, all protein.ligand combinations were screened individually in a directed screen. For all assays the protein concentration was 10 μM in 20 μL reactions. Ligand final concentration in initial screens was 1000 μM, resulting in a 100 fold molar excess of small molecule to protein. The protein melting temperature (Tm) was determined by manual inspection of the first derivative curve generated by LightCycler480 analysis software (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA). All reported data represent an average of at least three experimental replicates.

In our analysis, a chemical was considered a “binding ligand” if the calculated NTm (relative to the Tm without ligand) was greater than +2 °C. The NTm significance threshold is based on previous studies26,28 for this family of proteins as well as a qualitative assessment of the observed variation for proteins between the various assays (individual ligand screens, replicates, and concentration.dependent assays). For ligands in DMSO or nonstandard HEPES buffer, the volume of added ligand solution was limited to maximum of 2% of the total reaction volume to minimize solvent or pH effects on protein stability. Assay protocols also included solvent.only controls to identify ligand solvent effects. The observed Tm variations for these solvent.only controls were 1°C or less.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

For intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence measurements, the protein was excited at 275 nm in the presence of varying concentrations (30μM.8mM) of ligand. Changes at the emission maximum were monitored as a function of ligand concentration and binding curves were fitted using Origin graphing software. The fitting parameters assumed single site binding and binding constants calculated based on fractional saturation. The fractional saturation, Y, is defined as the fraction of protein molecules that are saturated with ligand .This relationship of fractional saturation to ligand concentration [L] and KD can be expressed as Y = [L]/(KD+[L]). In the case of a protein that binds only one ligand it is the same as the ratio of the moles of ligand bound/mole of protein. The KD was calculated as the concentration where protein was half saturated with ligand. The presented results represent the average of two independent experiments.

Cloning

B. japonicum USDA 110 cells were obtained from Gary Stacey, University of Missouri at Columbia. Genomic DNA from B. japonicum was purified from cultures grown in HM-YA media using a ZymoBead Genomic DNA kit (#D3004, Zymo Research, Irvine, California, USA). Genomic DNA purchased from ATCC (Manassas, Virginia, USA) was used for R. palustris strains CGA009 (ATCC# BAA-98), HaA2 (ATCC# BAA-1122D.5), and BisB5 (ATCC# BAA-1123D-5). Genes included in the cloning set included proteins encoded at the following loci: RPB_3575, RPB_4630, RPD_1520, RPD_1889, bll6825 and blr7848. All SBP coding regions were analyzed for signal peptide sequences using SignalP29 and TatP30 prediction algorithms; signal peptides were excluded from the cloned region resulting in expression of only the predicted mature protein. Primers were designed using a high-throughput primer design tool31 and ordered from IDT (Coralville, Iowa, USA). Sequences were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA, fused to an N-terminal hexahistidine tag in an E. coli cytoplasmic expression vector and used to generate an E. coli production strain as described previously26,32. All targets were sequenced to verify correct insertion of the coding region. Reference proteins RPA1789 and RPA4648 were produced from vectors constructed in previous experiments26. Small-scale heterologous protein expression in E. coli and IMAC purification using fused hexahistidine tags was carried out as described previously to generate protein utilized in FTS assays26.

Protein expression, purification and crystallization

The selenomethionine (SeMet) derivative for all fusion protein was prepared as described previously33. The BL21(DE3)/pMAGIC were grown at 37°C in M9 medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 8.5 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4, and 1% thiamine. After the OD600 reached 1.0.1.5, 0.01% (w/v) each of leucine, isoleucine, lysine, phenylalanine, threonine, and valine were added to inhibit the methionine metabolic pathway and increase SeMet incorporation. SeMet was added to the culture (60 mg SeMet per liter culture), and protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 18°C overnight. Cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer and stored at –80°C.

Fusion protein was purified according to a standard protocol34. Lysozyme (final concentration of 1 mg/mL) and 1 protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, complete ULTRA, Branchburg, NJ) were added to the thawed cell suspension. The solution was incubated on ice for 20 min and lysed by sonication. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 36,000 × g for 1 h and filtered through a 0.44 μm membrane. Clarified lysate was applied to a 5 mL HiTrap Ni- NTA column (GE Health Systems) on an ÄKTAxpress system. The column was washed with lysis buffer containing 20 mM imidazole and the protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Sample was concentrated and subjected to an additional purification step on a Superdex 200 10/30 size exclusion chromatography column equilibrated with crystallization buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT. Fractions containing monomeric protein were identified by SDS.PAGE and then concentrated for crystallization experiments to 35.40 mg/mL (i.e. ~1 mM). RPD1520 was not included in crystallization trials as it was difficult to purify to levels required for crystallization screening and precipitated at high protein concentrations.

Crystallization screening was set.up with the help of a Mosquito liquid dispenser (TTP LabTech, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) using the sitting.drop, vapor.diffusion method in 96- well CrystalQuick plates (Greiner Bio.One, Monroe, North Carolina, USA) at 16°C. For co- crystallization trials, ligands were used at a 5.10 fold molar excess over protein concentration. For each condition, 0.4 ML protein solution and 0.4 μL crystallization formulation were mixed and the mixture was equilibrated against a 135 μL reservoir. The suite of four MCSG crystallization screens (Microlytic, Inc., Burlington, MA) was used and diffraction quality crystals typically appeared within 3.7 days.

Protein refolding

A subset of proteins were subjected to small.scale denaturation and refolding experiments to determine if proteins purified from E. coli cell culture contained pre.bound ligands. Purified protein in 1x HEPES buffer was thawed and diluted to less than 1 mg/mL with denaturation buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 6 M urea). Denatured protein was dialyzed against denaturation buffer with three buffer exchanges to remove pre.bound ligands. SBPs were refolded by transferring the sample to 1x HEPES buffer and removing urea with three buffer exchanges. All dialysis steps were carried out at 4°C. After buffer exchange samples were centrifuged at 15,000 RPM for 10 minutes to pellet precipitates; supernatant was then concentrated for use in FTS assays. Refolded proteins were used immediately in FTS assays and stored for no longer than a week at 4°C. Screens were performed as described above with an untreated protein sample run side-by-side for comparison.

Data collection

Prior to X-ray diffraction data collection, the crystals of RPB4630, RPA1789, RPB3575 and RPD1889 were treated in their mother solutions supplemented with cryoprotectants and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. A set of single.wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) or multiple. wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data was collected near the selenium absorption edge at 100 K from a single SeMet labeled crystal of each project. The data were obtained at the 19- ID beamline of the Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory using the program SBCCollect. The intensities were integrated and scaled with the HKL300035 suite

Structure solution and refinement

All the structures were solved by anomalous diffraction methods (SAD or MAD) using the HKL3000 software suite35. Selenium sites were located by SHELXD and the handedness was determined by SHELXE36. Phasing was performed with iterative cycles of MLPHARE37, followed by density modification procedure in DM38. The initial protein models were built in ARP/wARP39. All of the above programs are integrated within the program suite HKL3000. Further model building to complete the structures was performed manually using the program COOT40. The model was refined using the program Phenix.refine41 or Refmac42.

PDB accession codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the following accession codes: RPB4630/BZF, 3SG0; RPB4630/PPY, 4DQD; RPB3575/HPP, 3UKJ; RPB3575/COU, 4EYO; RPA3575/HPP+CAF, 4EYQ; RPA1789/HPP, 3TX6; RPA1789/COU, 4F8J; RPA1789/CAF, 4FB4; RPD1889/HPP, 3UK0; RPA4648, 3RPW; BLL6825, 4FCL.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were built using the a la carte function on the Phylogeny.fr server (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/index.cgi)43. Protein sequences were aligned using clustalW and phylogenetic distance calculated using PhyML. The resulting tree was edited using the Drendrodscope program44.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Target selection for structure-function studies

Since few proteins have been characterized as binding phenylpropanoid compounds, we used multiple strategies to select candidates for ligand binding screens and subsequent functional characterization. In one approach, sequences of the reference proteins RPA1789 and RPA4648 and the BLAST algorithm27 were used to identify similar sequences encoded in the genomes of other soil organisms; Nitrobacter winogradskyi Nb.255, Sinorhizobium meliloti (syn:Ensifer meliloti 1021), B. japonicum USDA 110, and multiple R. palustris ecotypes. In an attempt to focus on SBPs with aromatic acid binding capabilities we initially limited our selection to proteins with greater than 50% sequence identity45,46. This approach resulted in the selection of four targets (Protein IDs: RPB3575, RPD1889, RPE3800, and BLR7848) with greater than 80% sequence identity to RPA1789. Sequence analysis of the R. palustris HaA2 (RPB) and BisB5 (RPD) strains, as well as B. japonicum USDA 110 genome identified additional SBPs with ~40% sequence identity to RPA1789. One protein (Protein ID: RPB4630) was selected as a representative of this group for ligand binding screens to determine if these proteins also have aromatic acid binding capabilities.

The RPA4648 protein exhibited a low level of thermal stabilization in the presence of p- coumaric acid in a previous FTS screen26. A genome-wide search for homologs in the selected Alphaproteobacterial species yielded no encoded proteins with greater than 50% sequence identity to the RPA4648 reference sequence. However, the BLL6825 protein from B. japonicum USDA 110 shares 38% sequence identity with the RPA4648 protein and was included in the set for structural and functional characterization to evaluate the limits of sequence conservation for this family of SBPs.

In a parallel approach to sequenced.based ligand prediction, we utilized literature searches and genome context to identify an additional target for characterization. The RPD1520 protein encoded in the genome of the R. palustris BisB5 strain shares only 28% sequence identity with RPA1789 from the R. palustris CGA009 strain, which is too low to predict aromatic.binding activity with confidence. However, this transporter is located in an operon with predicted phenylacetic acid degradation genes (PadBCDEFGHI; RPD_1507 to RPD_1514) in the only sequenced R. palustris strain with known phenylacetic acid degradation capabilities47.

Based on this genomic location and experimentally characterized strain phenotype, we included this protein in the target set for the ligand binding screens.

Screening library design

Biological degradation of lignin results in a complex assortment of compounds that hve been partially characterized by mass spectroscopy48.50. This complexity is attributable to the highly reactive but nonspecific free radicals that accomplish lignin fragmentation and the variability between lignin samples. One strategy for categorization of these numerous products is to group compounds in accordance with the cellular pathways that activate these structurally diverse substrates and funnel compounds to central metabolic pathways4,7,8. This process results in 5-8 groups of lignin-derived compounds based on metabolic entry point7. We used this information to diversify our previous screening library to a total of 39 aromatic compounds which encompass many of the native compounds derived from lignin. Expansion of aromatic ligands in this screen took into account a variety of considerations, beginning with the ring structures of the basic lignin monomers. Plant monolignol subunits have para-hydroxylated rings, with 0, 1, or 2 methoxyl groups at the meta position. Substrates for the FTS library were chosen so that most of them would have ring substitutions in similar locations and types as the monolignol precursors..primarily para- and meta-hydroxylations and methoxylations. Analyses of fungal breakdown products reveals some small molecules with ortho- substitutions, so a small number of these have been included as well (i.e. salicylic acid, gentisic acid)51. Substitutions at the first ring carbon atom include carboxylic acids, aldehydes, acetic acids, propanoic acids and propenoic acids. This set also contains a limited number of small molecules that are not associated with lignin degradation, but which could be relevant ligands in the soil environment. For example, all three proteinogenic aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan) were included as these amino acids are necessary for growth and there is the possibility that transporters for these substrates may show cross.specificity with structurally similar molecules. Catechol and cis,cis-muconic acid are products of aerobic bacterial metabolism of aromatics. Shikimic acid and quinic acid are non-aromatic cyclic molecules that are precursors to both aromatic amino acid synthesis and phenylpropanoid synthesis, so it is possible that these molecules are also present in the soil environment. Other non-aromatic small molecules include short chain fatty acids, used to test dependence on aromatic ring structures for protein-ligand interaction. Benzamide and benzonitrile are generally present in the environment as pollutants but some microbial species show capabilities for degradation of xenobiotic aromatic molecules. A complete list of all ligands used in this screen is presented in Supplemental Table S1. The overall composition of the screening library is representative of the chemical profiles obtained by analysis of fungal lignin degradation products by mass spectrometry51.

Ligand binding profiles for diverse SBPs

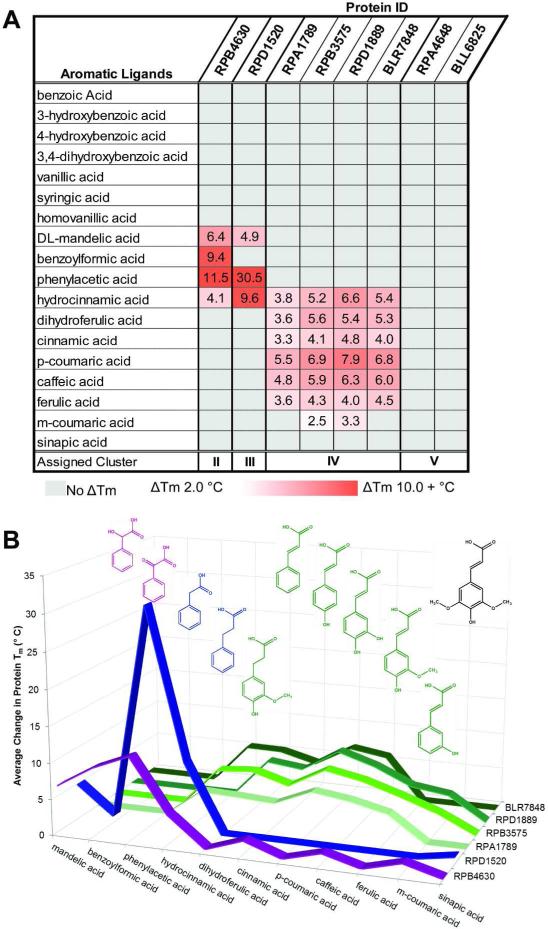

A FTS screen was used to characterize eight SBPs for ligand-mediated thermal stabilization as an indicator for protein-ligand interaction. FTS screening methods are widely used for ligand identification but do not provide sufficient thermodynamic parameters to directly infer binding constants from thermal stabilization profiles52. However, studies have shown that the FTS assay results typically emulate ligand binding profiles obtained through alternative approaches and the rank order of ligand binding generally correlates with affinity constants28,52,53. A summary of calculated differences in melting temperatures (NTm) obtained via the FTS screen is presented in Fig. 1, with the full listing of results presented in Supplemental Table S2. Organization of the thermal stabilization data by ligand chemical features allows these proteins to be grouped into four separate clusters based on ligand-binding specificity. The observed thermal stabilization for Clusters II, III and IV varies according to the size and number of aromatic ring substituents. All clusters are stabilized with acetic or propanoic acid functional groups. However, cluster IV proteins were observed to interact with multiple ligands that have hydroxylations and methoxylations at para- and meta-ring positions. This binding profile is distinct from cluster I solute binding proteins12 which recognize various benzoate derivatives.

Fig. 1.

Fluorescence Thermal Shift Assay results for uncharacterized SBPs. The calculated NTm represents the difference in the Tm of protein mixed with prospective ligands and the Tm of protein-only reactions. Values are an average of at least three replicates. Average standard deviations for cluster II protein.ligand experimental measurements is 0.42 °C (0-0.78 °C range); cluster III is 0.66 °C (0-10.3.17 °C); cluster IV is 0.38 °C (0-0.94 °C). A.) This chart lists the NTms of all proteins with a selection of lignin derivatives. Cells are colored in a white to red gradient based on magnitude of the NTm. Ligands with increasing ring substitution are arranged in the top section (benzoic acid to syringic acid) followed by molecules with both increasing chain lengths and ring substitutions (homovanillic acid to sinapic acid). B.) Chart illustrating overlap in binding specificity. Structures of ligands are colored to match the cluster that shows binding activity. Cluster II (magenta) and cluster III (blue) both bind phenylacetic acid, but there is little overlap with the ligands that interact with cluster IV (green) SBPs. No protein shows a large shift with sinapic acid, which has been colored black.

The RPD1520 protein had no previously characterized homologs but close proximity to the phenylacetic acid-degradation gene cluster suggested that it would bind phenylacetic acid. FTS results support this assumption with large Tm shifts when phenylacetic acid or hydrocinnamic acid were included in the thermal denaturation reaction. Although the RPB4630 and RPD1520 proteins both preferentially bind phenylacetic acid the secondary binding activity suggests that they may be optimized for addition compounds with different chain structures. The specificity profile of RPD1520 shows stabilization with unsubstituted aromatic rings and saturated carbon.only chains. The presence of a hydroxyl group or keto group on the aliphatic chain negatively impacts thermal stabilization. Tm shifts were significantly reduced with DL- mandelic acid, benzoylformic acid and homovanillic acid, and no interaction was observed with cinnamic acid. The results suggest this transporter complex may have a role for import of aromatic substrates with longer carbon chains as well as phenylacetic acid. In contrast, the RPB4630 protein exhibited minimal or no stabilization in the presence of ligands containing longer carbon chains (i. e. hydrocinnamic acid, cinnamic acid) but considerable stabilization with benzoylformic acid and DL-mandelic acid (Fig. 1). These observations motivated the separation of RPB4630 and RPD1520 proteins into separate clusters II and III.

Cluster IV SBPs bind ligands that contain a 2-propenoic acid or propanoic acid chain attached to the benzyl ring. Ligands with hydroxyl groups on the 4- or 3,4-ring carbons (p- coumaric acid, caffeic acid) produce the maximal observed thermal shifts. Methoxyl groups at the 3 ring position are allowed (ferulic acid) but thermal stabilization is reduced. Notably, there is no binding observed with sinapic acid, which has methoxyl groups on both the 3 and 5 ring carbon atoms.

The BLL6825 and RPA4648 SBPs share relatively low sequence identity and a ligand that induces high levels of thermal stabilization was not found for either target. The limited thermal stabilization observed with aromatic small molecules suggests the ligands reported here do not represent physiologically relevant substrates. As a result, both of these targets have been grouped into cluster V. These proteins are both annotated as spermine/putrescine.binding SBPs, however FTS assays with these small molecules also did not induce thermal shifts (data not shown).

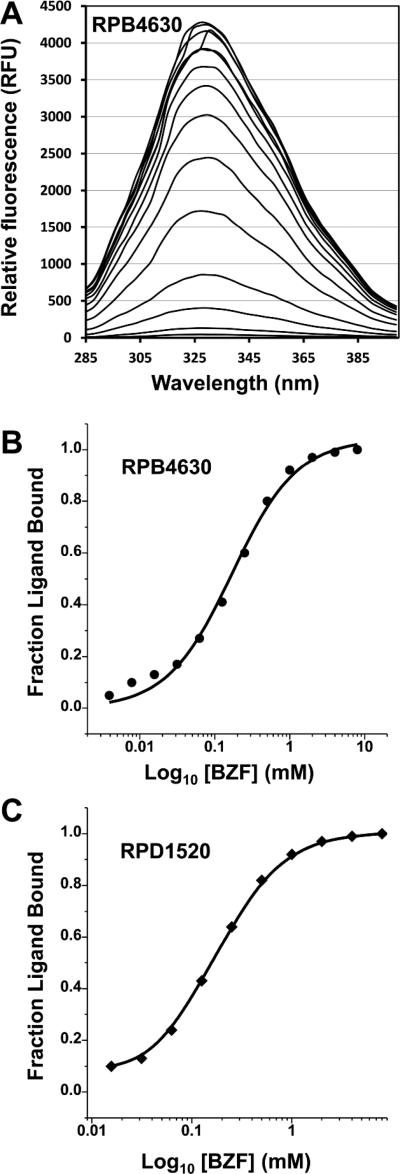

Fluorescence spectroscopy and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

To provide additional insight into the binding features of these proteins we used fluorescence spectroscopy to examine the protein=ligand interactions of cluster II and III proteins. The RPB4630 (cluster II) and RPD1520 (cluster III) proteins both contain two tryptophan and 12 tyrosine residues. The analysis focused on the effect of phenylacetic, benzylformic and hydrocinnamic acid as this set of compounds exhibited thermal stabilization of both proteins in the FTS assay. In addition, the biophysical properties of these small molecules are compatible with analysis of protein fluorescence in the 300-350 nm region of the spectrum. A similar pattern of results was observed for both the RPB4630 and RPD1520 proteins (Fig. 2). Substantial changes in the protein florescence intensities in the 300-340 nm region were only observed upon the addition of benzylformic acid (BZF) with only minor changes in the fluorescence spectra were observed upon the addition of phenylacetic or hydrocinnamic acid. Analysis of the relationship of fractional saturation to ligand concentration (Fig. 2) yields calculated KD values of 1.70 × 10.4 M.1 ± 0.13 for the BZF-RPB4630 and for 1.50 × 10.4 M.1 ± 0.11 for BZF-RPD1520. The results indicate BZF is a relatively weak binding ligand and can only be taken as a guide towards the true ligand, whose identification will require further experimentation.

Fig. 2.

BZF Quenching of RPB4630 and RPD1520 protein fluorescence. (A) Quenching of RPB4630 protein fluorescence by BZF. The protein was excited at 275 nm in the presence of varying concentrations (30uM.8MM) of BZF and fluorescence recorded in the range of 285 to 400 nm. (B) BZF quenching of RPB4630 and (C) RPD1520 intrinsic protein fluorescence. Reduction of tryptophan fluorescence is shown as a fraction of the starting fluorescence and is plotted versus the concentration of BZF. The lines superimposed on the data represent an optimal fit of the data as described in the Methods section. Refolded RPB4630 protein prepared as described in the Methods was used for the interaction studies.

Fluorescence spectroscopy was not suitable for many compounds that stabilize proteins in cluster IV as they absorb in the 300-350 nm region of the UV spectrum, overlapping with tryptophan and tyrosine absorbance wavelengths. However, we recently studied several SBP. ligand combinations54 with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Our analysis of a cluster IV representative, the RPA1789 protein, suggested a preference for propenoid ring substituents, which was confirmed by the observation of specific binding to p-coumaric acid at an observed Kd of 8.6 μM54. In this case, the ITC results are consistent with the protein.ligand interactions identified via FTS screening assays and this Kd value in the micromolar range is similar to ligand affinities reported for other characterized SBPs.

Structures of RPB4630 (cluster II)

RPB4630 protein was screened for crystallization under multiple conditions. Purified native sample was screened alone or mixed with a 10-fold excess of benzoylformic acid (BZF) to generate a structure complexed with aromatic ligand (Table I). The structure derived from the native RPB4630 contains a pre-bound ligand, 3.phenylpyruvic acid (PPY) in the ligand-binding pocket. In the co-crystal structure the pre-bound ligand has been completely replaced by the supplemented ligand BZF. Both crystal structures have been determined to high-resolution; 1.2 Å for RPB4630/BZF and 1.6 Å for RPB4630/PPY (Table I). In both structures, there is one RPB4630 protein chain in each asymmetric unit and the molecular packing unambiguously indicates that the SBP is monomeric55. No significant conformational change is observable for the two RPB4630 structures with different ligands as the root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) value from a secondary structure matching (SSM)56 alignment is 0.20 Å without any gaps.

Table I.

Crystallographic Statistics

| RPB4630/BZF | RPB4630/PPY | RPA3575/HPP | RPA3575/COU | RPA3575/HPP+CAF | RPA1789/HPP | RPA1789/COU | RPA1789/CAF | RPD1889/HPP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||||

| Space group | P212121 | C2 | P212121 | P6522 | P6522 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit Cell (Å, °) |

a=62.49, b=70.30, c=98.27 |

a=125.0, b=62.42, c=60.62, β=113.7 |

a=42.69, b=70.31, c=104.69 |

a=b=88.34, c=209.9 |

a=b=88.34, c=209.9 |

a=48.56, b=68.67, c=90.78 |

a=48.87, b=69.01, c=91.31 |

a=48.99, b=71.06, c=91.02 |

a=43.27 b=71.58 c=105.00 |

| MW Da (residue) | 38248 (360)1 | 38248 (360)1 | 38455 (359)1 | 38455 (359)1 | 38455 (359)1 | 38415 (359)1 | 38415 (359)1 | 38415 (359)1 | 38590 (359)1 |

| Mol (AU) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SeMet (AU) | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9793 (peak) | 0.9793 (peak) | 0.9792 (peak) | 0.9792 (peak) | 0.9792 (peak) | 0.9792 (peak) 0.9794 (inflect.) |

0.9793 (peak) | 0.9793 (peak) | 0.9792 (peak) |

| Resolution (Å) | 38.6-1.20 | 26.0-1.60 | 50.0-1.60 | 50.0-1.70 | 50.0-1.95 | 50.0-1.50 | 36.6-1.60 | 35.5-1.85 | 42.3-1.49 |

| Number of unique reflections | 1345152 | 562112 | 420822 | 546122 | 350132 | 492242 | 414162 | 275972 | 535602 |

| Redundancy | 7.0 (4.5)3 | 3.7 (3.7)4 | 6.5 (5.6)5 | 6.4 (4.7)6 | 8.2 (7.8)7 | 8.6 (7.9)8 | 10.3 (10.4)9 | 7.8 (7.5)10 | 13.1 (6.7)11 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (95.9)3 | 99.9 (100.0)4 | 98.8 (97.5)5 | 99.1 (93.5)6 | 97.5 (96.8)7 | 99.4 (98.0)8 | 99.8 (100.0)9 | 98.9 (96.6)10 | 97.8 (80.8)11 |

| Rmerge (%) | 9.6 (55.7)3 | 9.8 (57.3)4 | 9.8 (58.9)5 | 11.3 (73.4)6 | 15.3 (80.3)7 | 7.5 (45.9)8 | 8.1 (49.4)9 | 8.5 (68.4)10 | 9.9 (63.8)11 |

| I/σ(I) | 44.6 (2.5)3 | 23.0 (2.5)4 | 31.9 (2.5)5 | 30.4 (2.1)6 | 25.3 (3.7)7 | 10.8 (2.4)8 | 9.0 (3.4)9 | 9.2 (3.1)10 | 10.3 (2.1)11 |

| Phasing | |||||||||

| RCullis (anomalous) (%) | 37 | 71 | 50 | 7612 | 85 | 35 (peak)12 44 (inflection)12 |

53 | 70 | 52 |

| Figure of merit (%, before DM) | 52.4 | 29.2 | 41.2 | 23.412 | 16.1 | 65.412 | 39.4 | 27.8 | 39.4 |

| Refinement | |||||||||

| Refinement Program | Phenix | Phenix | Refmac | Refmac | Refmac | Refmac | Refmac | Refmac | Refmac |

| Resolution | 38.6-1.20 | 26.0-1.60 | 34.5-1.60 | 40.72-1.70 | 36.81-1.95 | 50.0-1.50 | 36.6-1.60 | 35.5-1.85 | 42.3-1.49 |

| Reflections (work/test) | 125109/6639 | 53302/2848 | 39905/2127 | 51767/2713 | 33127/1741 | 46551/2483 | 39149/2075 | 24238/1290 | 50658/2698 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 15.0/16.2 | 14.3/16.2 | 15.9/20.0 | 17.1/22.5 | 15.4/20.4 | 13.7/19.8 | 15.7/19.2 | 16.6/21.3 | 13.6/19.4 |

| Rms deviation from ideal geometry Bond length (Å)/angle (°) |

0.005/1.110 | 0.006/1.099 | 0.015/1.430 | 0.013/1.504 | 0.012/1.464 | 0.015/1.696 | 0.014/1.713 | 0.015/1.594 | 0.015/1.648 |

| No.of atoms (Protein/HETATM) | 2774/602 | 2690/461 | 2694/495 | 2695/321 | 2722/308 | 2789/536 | 2744/540 | 2632/218 | 2765/381 |

| Mean B-value (Å2) (mainchain/sidechain) |

12.4/16.9 | 21.0/23.4 | 15.7/17.6 | 27.3/30.4 | 25.8/28.7 | 20.9/24.3 | 23.4/25.5 | 22.46/25.29 | 24.1/28.4 |

| Ramachandran plot statistic (%) | |||||||||

| Residues in most favored regions, in additional allowed regions, in generously allowed regions, in disallowed region |

92.9 7.1 0.0 0.0 |

92.9 7.1 0.0 0.0 |

93.0 7.0 0.0 0.0 |

92.5 7.5 0.0 0.0 |

92.2 7.8 0.0 0.0 |

93.1 6.9 0.0 0.0 |

92.8 7.2 0.0 0.0 |

94.8 5.2 0.0 0.0 |

93.8 6.2 0.0 0.0 |

| PDB Entry | 3SG0 | 4DQD | 3UKJ | 4EYO | 4EYQ | 3TX6 | 4F8J | 4FB4 | 3UK0 |

Not including cloning artifact

Including Bijvoet pairs

(Last resolution bin, 1.20-1.22 Å)

(Last resolution bin, 1.60-1.62 Å)

(Last resolution bin, 1.50-1.55 Å)

(Last resolution bin, 1.70-1.72)

(Last resolution bin, 1.95-1.97)

(Last resolution bin, 1.50-1.53 Å)

(Last resolution bin, 1.60-1.63 Å)

(Last resolution bin, 1.85-1.88 Å)

(Last resolution bin, 1.49-1.52 Å)

Phasing high resolution limit was 2.0 Å

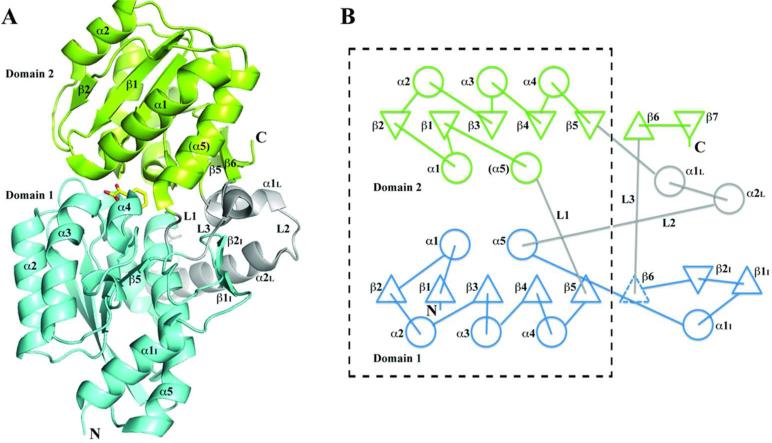

The overall structure (Fig. 3) indicates the protein is a member of Class I SBPs according to the classification scheme proposed by Fukami-Kobayashi57 or cluster B in the Berntsson structural classification scheme25. The RPB4630 molecule consists of two intertwined domains of α/β/α layers. The two domains are connected by three linkers, which form a hinge between the domains. Although the two SBP lobes have similar overall folds, the N.terminal domain 1 (172 a.a.) is much larger than the C-terminal domain 2 (142 a.a.) and their primary sequence identity is only 12.3%. A SSM superimposition of the two domains yields an rmsd value of 2.93 Å with 114 amino acid residues aligned and 10 gaps. The largest difference between the two lobes involves an insertion (Thr330-Asn360) within Domain 1 (Fig. 3A, B).

Fig. 3.

Structure of the RPB4630 protein. (A) A cartoon diagram of the RPB4630/BZF structure with domain 1 drawn in cyan and domain 2 in green. The three linkers between these domains (L1, L2 and L3) are colored in gray. The ligand, BZF, is positioned in the binding site between two domains and drawn in stick format. Only those secondary structures in the front view are labeled for clarity of the figure. (B) The topological representation of the RPB4630 structure. The dashed line box includes the core of the structure. In domain 1, an expected β6. strand drawn in dashed triangle is absent due to the lack of the backbone.backbone hydrogen bonds between β5 strand and the peptide portion that runs parallel to the β5 strand. The α1I helix and the β.hairpin (β1I and β2I) are parts of the insertion between α5 helix and the expected β6. strand. Domain 2 starts from α5 helix, in contrast to domain 1, which starts from β1 and end with α5. Its β6.strand is antiparallel to the strands of the central β.sheet. One of the three linkers (in gray), L2, includes two helices, α1L and α2L.

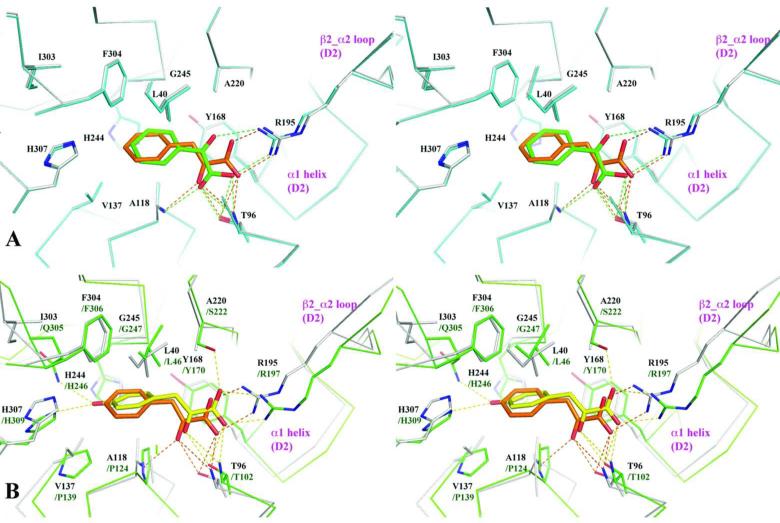

The ligand-binding site resides in the cleft between domains 1 and 2 (Fig. 3A) and is a largely hydrophobic pocket formed by the residues Leu40, Ala117, Ala118, Val137, Tyr168, Ala220, His244, Gly245 and Phe304 (Fig. 4A). When the two ligand-complexed structures are superimposed the aromatic rings of PPY and BZF are nearly overlapped with the ring of PPY shifted slightly inward (~ 0.6 Å) towards the hinge region. The aliphatic tails of both ligands are also nearly planar, parallel to the phenyl ring of Tyr168 but skewed at an approximately 45° angle to the aromatic ring of the ligands.

Fig. 4.

Stereoview of ligand coordination in the RPB4630 and RPB3575 structures. (A) Stereoview illustration of the structurally aligned ligand-binding sites of RPB4630 with pre- bound phenylpyruvic acid (PPY) and substituting ligand, benzoylformic acid (BZF). RPB4630/PPY is in cyan and RPB4630/BZF is in gray. The residues that form the ligand. binding site of RPB4630 and the ligands are drawn in stick format. The carbon atoms of PPY and BZF are drawn in orange and green, respectively. Hydrogen bonds (2.50-3.50 Å) and salt bridges are drawn as dashed lines in colors corresponding to the ligands. (B) Stereoview illustration of the structurally aligned ligand.binding sites of RPB4630 (in grey) and RPB3575 (in green) with their pre-bound ligands, phenylpyruvic acid (PPY, C atoms in orange) and 3-(4- hydroxyl)phenylpyruvic acid (HPP, C atoms in yellow), respectively. Corresponding ligand. binding site residues are labeled in pairs with those from RPB4630 in black and those from RPB3575 in green, respectively. The limited local conformational changes (a tilt of α1 helix and a shift of β2_α2 loop in domain 2) observed in RPB3575/PPY relative to RPB4630/HPP likely reflect an accommodation of the larger HPP molecule.

The aromatic rings of both ligands and the sidechain ring of Phe304 positioned at the bottom of the binding pocket are almost perpendicular to each other with centroid.centroid distance of about 5.4Å16. The aromatic.aromatic interaction is the only apparent specific interaction involved with the aromatic portion of a ligand in the binding site. Near the opening of the binding site, the acidic tails of both ligands interact with residue Arg195, which appears to cap the pocket. In the RPB4630/PPY structure, the carboxyl group of pyruvic acid forms a bidentate salt bridge to Arg195 and one hydrogen bond to the amide group of Thr96. The ketone group on the pyruvic acid forms three additional H-bonds to the sidechain of Thr96 and the amide groups of Thr96 and Ala118, respectively. The RPB4630/BZF structure shows an altered pattern of hydrogen bonds between protein and ligand, but with the same number of hydrogen bonds.

The main difference between the two ligands found in the RPB4630 binding pocket is the length of the aliphatic tails; PPY has a 3-carbon chain and BZF has only a 2-carbon chain. The slightly larger PPY ligand is accommodated by slight changes in both the position of the ligand and the shape of the binding pocket. The hydrophobic bottom of the binding pocket is quite rigid and there is no apparent conformational change in this region between the two complex structures. However, in RPB4630/PPY structure, the ligand seems to be pushed deeper towards hydrophobic bottom (~ 0.6 Å) of the pocket. In contrast, the opening of the pocket shows some plasticity to accommodate ligands with different chain lengths. The guanidinium group of the capping residue Arg195 is moved backward approximately 0.4 Å to make room for the 3-carbon PPY ligand tail. This is achieved by both movement of the residue sidechain as well as the β2_α3 loop where Arg195 is located. Though possibly limited, the flexibility of the binding pocket at the opening suggests the potential to accommodate ligands with different tails.

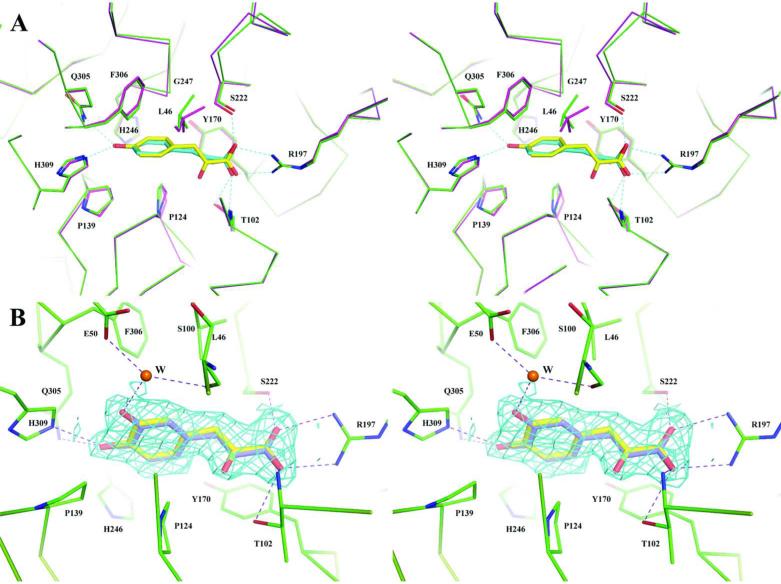

Structures of RPA1789, RPB3575 and RPD1889 (cluster IV)

Crystallization screens were conducted for RPA1789, RPB3575, RPD1889 and BLR7848 with native protein alone and protein supplemented with a 10-fold excess of p-coumaric acid (COU) or caffeic acid (CAF). These ligands were chosen for co.crystalization as they gave the highest levels of thermal stabilization in FTS assays. Experiments with BLR7848 failed to yield crystals, however RPA1789, RPB3575 and RPD1889 proteins successfully crystallized under multiple conditions (Table I). The pairwise primary sequence identities of the mature forms of these three cluster IV transporters are between 90.4 and 95.8%. Analysis of the electron density indicates these “apo” structures all contain 3-(4-hydroxyl) phenylpyruvate (HPP) in the ligand binding pocket although their crystallization conditions are very different. Structures for RPA1789 and RPB3575 proteins in complex with p-coumaric acid (COU, 4-hydroxycinammic acid) or caffeic acid (CAF, 3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid) were obtained from co-crystallization trials. The conformation of all ligand-bound protein structures is largely the same, with the rmsd values of SSMs ranging from 0.38 Å to 0.46 Å. The molecular details of RPB3575/HPP, RPB3575/COU and RPB3575/CAF will be discussed to illustrate the structural features for this group of homologs.

RPB3575 (cluster IV) has an overall fold similar to RPB4630 (cluster II) described above (Fig. 3). A structural superposition yields an rmsd value of 1.45 Å with 341 out of 357 amino acids aligned with 6 gaps. Major differences are observed in their linker regions, especially in the long linker, L2 region. The ligand.binding site of RPB3575 (Fig. 4B) has features similar to those observed for RPB4630 consistent with their overall sequence identity of 41%. Several variations in amino acids lining the binding site are responsible for the ligand-binding specificity and altered ligand profile compared to RPB4630. The pre-bound ligand of all three cluster IV proteins is 3-(4-hydroxyl) phenylpyruvic acid (HPP), which has one additional para-hydroxyl group compared to the pre-bound ligand of cluster II, 3.phenylpyruvic acid (PPY). This suggests that the ligand specificity between these two clusters is largely determined by the bottom part of their ligand binding pockets. In RPB3575 there are two hydrogen bonds formed by Gln305 and His309 that coordinate the para-hydroxyl group on the benzyl ring of the HPP ligand (Fig. 4B). The His309 residue is conserved between RPB4630 and RPB3575. However, the residue corresponding to RPB3575 Gln305 in RPB4630 is a hydrophobic Ile303. The residues at these positions may be one determinant of the types of ligand ring structures that can be accommodated in the bottom of the SBP ligand.binding pockets. The position of the aromatic ring portion of the ligand is similar between protein structures. Pro124 in RPB3575 replaces Ala118 of RPB4630 causing the benzyl ring of the ligand to tilt away from the plane of the conserved Tyr170 sidechain. However, the ligand benzyl group is still oriented mostly perpendicular to the conserved Phe306 aromatic ring after rotation and thus maintains the T- shaped like π stacking that seems to be a hallmark in the ligand-binding pocket of these transporters. The interaction pattern involving the pyruvic acid tail of the HPP ligand is similar to that of 3-phenylpyruvate in RPB4630. RPB3575 makes one additional H-bond to the ligand hydroxyl group through Ser222, which is replaced by an alanine in RPB4630. The water molecule in the RPB3575 binding pocket is coordinated by hydrogen bonds to multiple amino acid residues; side chains of Glu50 and Ser100 and the backbone oxygen of Leu122.

The structure of RPB3575 with p-coumaric acid (COU) (Table 1) does not display any apparent conformational variation from the RPB3575/HPP structure. A SSM alignment results in a rmsd value of 0.42 Å. In the ligand binding pocket, the head benzyl ring and the tail hydroxyl group of two ligands are nearly overlapped with most interactions conserved between protein- ligand complexes. However, without the restriction of keto-enol tautomerism from the ketone group in HPP, the hydroxyl group can rotate out of the C=C double.bond plane. This additional free rotation of COU in the binding pocket may reduce the impact of the loss of three hydrogen bonds due to the absence of a ketone on the COU ligand.

RPB3575 incubated with caffeic acid (CAF) was isomorphous with the structures obtained for RPB3575/HPP or RPB3575/COU (Fig. 5A). However, the crystal structure shows a mixture of HPP and CAF in the ligand.binding site, indicating that CAF only partially replaced the pre.bound HPP. CAF has an additional meta-hydroxyl group compared to COU and HPP. A water molecule that is also conserved in RPB3575/HPP and RPB3575/COU structures interacts with the aromatic ligand, in a hydrogen bond between the water and the meta.hydroxyl group of CAF (Fig. 5B). The orientation of para- and meta-hydroxyl groups that point to the His309 sidechain seems to be energy unfavorable and it may overwhelm the gain from an extra H-bond formed from the hydroxyl group to the conserved water molecule. In contrast, in the structure RPA1789 incubated with CAF, the pre-bound HPP is completely replaced by CAF.

Fig. 5.

Stereoview of ligand coordination in the RPB3575 structure. (A) Drawings of the structurally aligned ligand.binding sites of RPB3575 with pre-bound 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid (HPP) and substituting ligand, p-coumaric acid (COU). RPB3575/HPP is in green and RPB3575/COU is in magenta. The residues that form the ligand.binding site of RPB3575 and the ligands are drawn in stick format. The carbon atoms of HPP and COU are drawn in yellow and cyan, respectively. Only hydrogen bonds (2.50-3.50Å) and salt bridge involved in COU are drawn in green dash lines. (B) Drawing of the ligand-binding site of RPB3575 (in green) with mixed ligands, pre-bound HPP (C atom in yellow) and substituting caffeic acid (CAF, C atoms in purple). A conserved water molecule in the binding pocket in all cluster IV is drawn as an orange sphere. The electron density map (2Fo-Fc) associated with the mixed ligands is drawn in cyan with a contour level of 1σ. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges involved in CAF and the conserved water molecule are indicated by purple dashed lines.

Predicted ligand-binding features of cluster III proteins

Although a structure was not obtained for RPD1520, the molecular details of the RPB4630 and RPB3575 structures provide some insight into the potential ligand-binding of this SBP cluster. The RPD1520 protein exhibits limited sequence similarity to RPB4630 or RPB3575, however the ligand-binding site residues are mostly conserved, especially those involved in benzene or phenyl head interactions found in RPB4630 and RPB3575 structures. This suggests that this SBP also binds aromatic compounds. The key difference between RPD1520 and RPB4630 or RPB3575 is the replacement of the capping arginine residue (RBP3575 Arg195 or RPB3575 Arg197) with a proline. In both RPB4630 and RPB3575 structures this arginine forms a bidentate interaction with the ligand and blocks the opening of the binding site. A substitution with proline will significantly affect interactions with potential ligands particularly their carboxylic acid tails. Structural homology modeling based on RPB4630 (31% identity/48% similarity) indicates that the ligand-binding pocket of RPD1520 tends to be more open, as expected17. Functionally, these SBPs exhibit markedly different levels of thermal stabilization associated with modification of the acidic group (Fig. 1). Both RPB4630 and RPD1520 exhibit maximum observed thermal stability when combined with phenylacetic acid. Benzoylformic or mandelic acid, which have a keto- or hydroxyl group at the β-carbon of the acid, confer good stability for RPB4630 while the longer, carbon.only chain hydrocinnamic acid induces better thermal stability for RPD1520. Crystallization efforts for the RPD1520 protein are ongoing as this structure would provide insight into the basis of preferred ligand selection for this SBP.

Structural comparison to cluster I

The ligand-binding sites of SBP cluster II, IV and likely cluster III are similar to each other. Key component residue alterations in the binding pocket could lead to the change in preferred ligands among phenylpropanoic acids and their derivatives. A previous study54, characterized several solute binding proteins that mediate the transport of smaller aromatic ligands such as 4- hydroxybenzoic acid (PHB). Like the ligands for cluster II and IV proteins, PHB also has an aromatic ring head and an acidic tail. However, the ligand-binding site of cluster I SBPs is completely different from cluster II and IV in both component residues and protein-ligand interaction patterns. Interestingly, a structural alignment of cluster I to cluster II or IV shows that the central β-sheets of the N- and C-terminal domains are aligned very well in all structures, suggesting that the relative positions of the two domains are conserved though the linkers are low in sequence and structural homology. For example, an alignment of RPA0668/PHB to RPB4630/PPY yields an rsmd value of 2.15Å with 10 gaps with alignment of 324 out of 360 residues from each molecule in this superposition. The major conformal changes occur in the long linker L2 region and edge helices, such as the α1 and α4 helices of both domains.

Pre-bound ligands

As described above, all cluster II and IV “apo” form transporters contained pre-bound ligands in the SBP binding pocket. To evaluate the consequences of the pre-bound ligand for interpretation of the in vitro ligand mapping by FTS native samples of RPB4630, RPD1520 and RPA1789 were refolded to produce SBPs that do not contain pre-bound ligands. Proteins RPB4630 and RPA1789 from cluster II and IV, respectively, appeared to successfully refold while RPD1520 precipitated during refolding. The functional properties of the native and refolded protein were assessed side-by-side using compounds that conferred the highest level of thermal stability (Fig. 1) based on the FTS assay results. We also assayed phenylalanine or tyrosine with refolded samples as these compounds are common cellular metabolites and have similar chemical features to the ligand found pre-bound to cluster II and IV proteins.

For RPB4630 and RPA1789, the baseline Tm of refolded proteins is 4 and 8° C lower than untreated sample, respectively, suggesting the pre-bound ligand has a role in the thermal stabilization of these transporter proteins (Supplemental Figure S1). Phenylalanine and tyrosine do induce thermal stabilization with the refolded protein, but do not restore the protein-ligand Tm to the level observed with the native samples with pre-bound ligands. When refolded SBPs are combined with previously-identified preferred ligands, however, the resulting Tm value is within 2° C of the shift observed with native samples. Consequently, the presence of a different ligand in the binding pocket did not prevent identification of preferred ligands for either of these proteins. However, detection of ligands that induce lower levels of thermal stabilization may be masked by the effect of the pre-bound ligand.

The source of the pre-bound ligands is expected to be the E. coli cell cytoplasm, where heterologous fusion proteins were overexpressed for protein production. PPY is an intermediate of phenylalanine metabolism and HPP is a predicted intermediate in both tyrosine metabolism and synthesis of ubiquinone58. These compounds are likely especially abundant in these protein production cultures as amino acid.rich media were used for bacterial growth. In the native bacterial host these SBPs would be secreted into the periplasm where the concentration of these cytoplasmic metabolites is expected to be lower.

Phenylalanine and tyrosine are also expected to be relatively abundant in E. coli cells but the SBPs did not co-purify with these compounds. Assuming that Phe and Tyr replace PPY and HPP in RPB4630/PPY and RPB3575/HPP, respectively, the amino groups would be in the same positions as the ketone groups of PPY and HPP. This would lead to unfavorable contact of the amino group with mainchain amide groups in the binding pocket. In all solved structures of Leu/Ile/Val-binding transporters, leucine-specific transporters or phenylalanine-binding transporters, there seems to be a conserved interaction pattern between these amino acids and the periplasmic binding protein type-1 superfamily members59.61. The amino group of any bound amino acid always interacts with either glutamate or aspartate and forms one or two H bonds. Meanwhile, the carboxyl group of the amino acid forms H bonds with one or two polar residues as well as one or two mainchain amide groups. The pattern is quite different from what is observed in the structures described in this study. This lack of amine group coordination may explain why phenylalanine and tyrosine did not induce the same levels of thermal stabilization in FTS assays as the pre-bound ligand (Supplemental Figure S1).

Structures of Cluster V SBPs

Structures were obtained from the both cluster V targets RPA4648 and BLL6825 in the apo conformation but neither protein crystallized with small molecules in the binding site. The targets exhibited relatively minor thermal stabilization profiles with the aromatic small molecules screened and the structures did not provide an indication of possible binding specificity. As such, it is difficult to determine the physiological function of these SBPs. However, the structures have been deposited in the PDB for future studies.

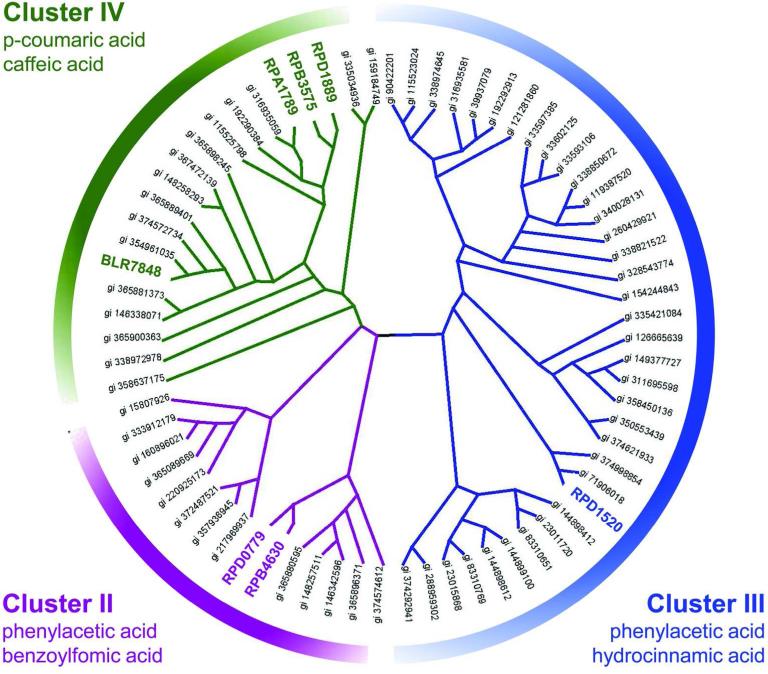

Evolutionary relationships and functional inference

Overlay of the chemical specificity on an unrooted phylogenetic tree suggest a consistent relationship between the binding profile inferred by the FTS assay and the phylogenetic relatedness (Fig. 6). Clusters II, III, and IV are grouped together but there are clear distinctions for cluster IV and the sequences represented by the RPB4630 (cluster II) and RPD1520 (cluster III) proteins. The cluster II-IV proteins also group separately from the cluster I proteins described elsewhere12.

Fig. 6.

Cladogram of homologs for the RPB4630, RPD1520, and RPA1789 proteins. BLAST was used to identify candidate sequences for analysis based on sequence identity to the RPB4630, RPD1520, and RPA1789 proteins. A phylogenetic tree was constructed as described in the Methods and the output represented as a cladogram.

Multiple R. palustris strains are known to be capable of growth on p-coumaric acid47,62.66. In addition, R. palustris utilizes p-coumaryl.HSL as a signaling molecule for quorum sensing67. Although growth of B. japonicum USDA 110 on p-coumaric acid has not been reported, it can grow on a number of potential intermediates of p-coumaric acid metabolism68. Consequently, the discovery of a p-coumaric acid transporter for these organisms agrees well with previous phenotypic characterizations of these species. The discovery of RPB4630 binding to benzoylformic acid is not supported by other evidence, however. A search of the KEGG database58 indicates that benzoylformic acid is not a common metabolite. However, it can be decarboxylated to benzaldehyde which can feed into benzoate degradation pathways. The two R. palustris strains (HaA2 and BisB5) that have a copy of this SBP (RPB_4630 and RPD_0779 loci, respectively) also have a predicted benzoylformate decarboxylase (MdlC) which would provide a route to utilize this aromatic acid. Many other bacteria also contain a homolog with greater than 50% protein sequence identity to RPA1789 and RPB4630, however most of them belong to Betaproteobacteria. Further studies will help identify if these transporters share ligand specificity or are involved in the transport of other aromatic small molecules.

The RPD1520 SBP was predicted to be a phenylacetic acid binding protein on the basis of genomic context47. FTS assay data apparently supports that role, as well as suggesting use for transport of hydroxycinnamic acid. Phenylacetic acid is produced during the breakdown of phenylalanine and multiple pathways exist to metabolize this compound. Since phenylacetic acid is generated in the cell cytoplasm there is not a strict requirement for a transporter. However, in carbon-limited environments phenylacetic acid could represent an attractive carbon source as pathways for utilization are pre-existing. Subsequently, the distribution of transporter complexes similar to RPD1520 need not be limited to soil bacteria with the capability for lignin degradation product metabolism. In fact, a BLAST27 search reveals that SBPs with similarity to RPD1520 have the widest distribution of any protein examined in this study. Representatives from all branches of proteobacteria as well as the firmicutes have a homolog of this protein.

The multiple crystal structures for protein-ligand complexes and functional screens provide new functional assignments or validate the current assignments that can be used to infer the transport specificity of ABC transporter complexes in related organisms. This functional information provides a mechanism to identify the specific enzymes and regulatory proteins of peripheral metabolic pathways that funnel these compounds to central metabolic pathways and will support sequence based methods for inference of protein function.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the members of the Structural Biology Center for their support and help in data collection. This contribution originates in part from the “Environment Sensing and Response” Scientific Focus Area (SFA) program at Argonne National Laboratory. This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER), as part of BER's Genomic Science Program. This research has been funded in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health grant GM094585, and by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under Contract DE. AC02.06CH11357.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP.binding cassette

- BCA

branched.chain amino acid

- BZF

benzoylformic acid

- CAF

caffeic acid

- CoA

coenzyme A

- COU

p.coumaric acid

- FTS

fluorescence thermal shift

- HPP

3.(4.hydroxy)phenylpyruvic acid

- HSL

homoserine lactone

- IPTG

isopropyl.β.D.thiogalactoside

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- MFS

major facilitator superfamily

- PAA

phenylacetic acid

- PHB

4.hydroxybenzoic acid

- PPY

3. phenylpyruvic acid

- rmsd

root.mean.square deviation

- SAD

single.wavelength anomalous diffraction

- SBP

solute.binding protein

- SeMet

selenomethionine

- Tm

melting temperature

- TLS

Translation/Libration/Screw

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as an ‘Accepted Article’, doi: 10.1002/prot.24305

REFERENCES

- 1.Ralph JL Knut, Brunow Goesta, Lu Fachuang, Kim Hoon, Schatz Paul F, Marita Jane M., Hatfield Ronald D., Ralph Sally A., Christensen Jorgen Holst, Boerjan Wout Lignins. Natural polymers from oxidative coupling of 4-hydroxyphenylpropanoids. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2004;3:29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong DW. Structure and action mechanism of ligninolytic enzymes. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;157(2):174–209. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandounas L, Wierckx NJ, de Winde JH, Ruijssenaars HJ. Isolation and characterization of novel bacterial strains exhibiting ligninolytic potential. BMC Biotechnol. 2011;11:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masai E, Katayama Y, Fukuda M. Genetic and biochemical investigations on bacterial catabolic pathways for lignin-derived aromatic compounds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71(1):1–15. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bugg TD, Ahmad M, Hardiman EM, Singh R. The emerging role for bacteria in lignin degradation and bio-product formation. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22(3):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown ME, Walker MC, Nakashige TG, Iavarone AT, Chang MC. Discovery and Characterization of Heme Enzymes from Unsequenced Bacteria: Application to Microbial Lignin Degradation. J Am Chem Soc. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ja203972q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmona M, Zamarro MT, Blazquez B, Durante-Rodriguez G, Juarez JF, Valderrama JA, Barragan MJ, Garcia JL, Diaz E. Anaerobic catabolism of aromatic compounds: a genetic and genomic view. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73(1):71–133. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs G, Boll M, Heider J. Microbial degradation of aromatic compounds - from one strategy to four. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(11):803–816. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko JJ, Shimizu Y, Ikeda K, Kim SK, Park CH, Matsui S. Biodegradation of high molecular weight lignin under sulfate reducing conditions: lignin degradability and degradation by-products. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100(4):1622–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelps CD, Young LY. Microbial Metabolism of the Plant Phenolic Compounds Ferulic and Syringic Acids under Three Anaerobic Conditions. Microb Ecol. 1997;33(3):206–215. doi: 10.1007/s002489900023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood CS, Parales RE. The beta-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:553–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalska K, Chang C, Mack JC, Zerbs S, Joachimiak A, Collart FR. Characterization of transport proteins for aromatic compounds derived from lignin: benzoate derivative binding proteins. J Mol Biol. 2012;423(4):555–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkinson S, Williams P. Quorum sensing and social networking in the microbial world. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6(40):959–978. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyer M, Wisniewski-Dye F. Cell-cell signalling in bacteria: not simply a matter of quorum. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;70(1):1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1125:82–99. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGaughey GB, Gagne M, Rappe AK. pi-Stacking interactions. Alive and well in proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(25):15458–15463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(2):195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson J, Dispensa M, Fogg GC, Evans DT, Harwood CS. 4-Hydroxybenzoatecoenzyme A ligase from Rhodopseudomonas palustris: purification, gene sequence, and role in anaerobic degradation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(3):634–641. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.634-641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samanta SK, Harwood CS. Use of the Rhodopseudomonas palustris genome sequence to identify a single amino acid that contributes to the activity of a coenzyme A ligase with chlorinated substrates. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(4):1151–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egland PG, Harwood CS. BadR, a new MarR family member, regulates anaerobic benzoate degradation by Rhodopseudomonas palustris in concert with AadR, an Fnr family member. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(7):2102–2109. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2102-2109.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz E, Ferrandez A, Garcia JL. Characterization of the hca cluster encoding the dioxygenolytic pathway for initial catabolism of 3-phenylpropionic acid in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(11):2915–2923. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2915-2923.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes MR, Duetz WA, Williams PA. A 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid catabolic pathway in Rhodococcus globerulus PWD1: cloning and characterization of the hpp operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(19):6145–6153. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6145-6153.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhry MT, Huang Y, Shen XH, Poetsch A, Jiang CY, Liu SJ. Genome-wide investigation of aromatic acid transporters in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiology. 2007;153(Pt 3):857–865. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Argenio DA, Segura A, Coco WM, Bunz PV, Ornston LN. The physiological contribution of Acinetobacter PcaK, a transport system that acts upon protocatechuate, can be masked by the overlapping specificity of VanK. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(11):3505–3515. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3505-3515.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berntsson RP, Smits SH, Schmitt L, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. A structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(12):2606–2617. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giuliani SE, Frank AM, Corgliano DM, Seifert C, Hauser L, Collart FR. Environment sensing and response mediated by ABC transporters. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-S1-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giuliani SE, Frank AM, Collart FR. Functional assignment of solute-binding proteins of ABC transporters using a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay. Biochemistry. 2008;47(52):13974–13984. doi: 10.1021/bi801648r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340(4):783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, Widdick D, Palmer T, Brunak S. Prediction of twin-arginine signal peptides. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon JR, Laible PD, Gu M, Scott HN, Collart FR. Express primer tool for high-throughput gene cloning and expression. Biotechniques. 2002;33(6):1328–1333. doi: 10.2144/02336bc03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zerbs S, Frank AM, Collart FR. Bacterial systems for production of heterologous proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2009;463:149–168. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh MA, Dementieva I, Evans G, Sanishvili R, Joachimiak A. Taking MAD to the extreme: ultrafast protein structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55(Pt 6):1168–1173. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999003698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim Y, Dementieva I, Zhou M, Wu R, Lezondra L, Quartey P, Joachimiak G, Korolev O, Li H, Joachimiak A. Automation of protein purification for structural genomics. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2004;5(1-2):111–118. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029206.07778.fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution--from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 8):859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr A. Vol. 64. Pt 1: 2008. A short history of SHELX. pp. 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otwinowski Z. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cowtan K. DM: An automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1994;(31):34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(7):1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50(Pt 5):760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie JM, Gascuel O. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huson DH, Richter DC, Rausch C, Dezulian T, Franz M, Rupp R. Dendroscope: An interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:460. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Addou S, Rentzsch R, Lee D, Orengo CA. Domain-based and family-specific sequence identity thresholds increase the levels of reliable protein function transfer. J Mol Biol. 2009;387(2):416–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian W, Skolnick J. How well is enzyme function conserved as a function of pairwise sequence identity? J Mol Biol. 2003;333(4):863–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oda Y, Larimer FW, Chain PS, Malfatti S, Shin MV, Vergez LM, Hauser L, Land ML, Braatsch S, Beatty JT, Pelletier DA, Schaefer AL, Harwood CS. Multiple genome sequences reveal adaptations of a phototrophic bacterium to sediment microenvironments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(47):18543–18548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809160105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kiyota E, Mazzafera P, Sawaya AC. Analysis of soluble lignin in sugarcane by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with a do-it-yourself oligomer database. Anal Chem. 2012;84(16):7015–7020. doi: 10.1021/ac301112y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morreel K, Dima O, Kim H, Lu F, Niculaes C, Vanholme R, Dauwe R, Goeminne G, Inze D, Messens E, Ralph J, Boerjan W. Mass spectrometry-based sequencing of lignin oligomers. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(4):1464–1478. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reale S, Di Tullio A, Spreti N, De Angelis F. Mass spectrometry in the biosynthetic and structural investigation of lignins. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2004;23(2):87–126. doi: 10.1002/mas.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez AT, Speranza M, Ruiz-Duenas FJ, Ferreira P, Camarero S, Guillen F, Martinez MJ, Gutierrez A, del Rio JC. Biodegradation of lignocellulosics: microbial, chemical, and enzymatic aspects of the fungal attack of lignin. Int Microbiol. 2005;8(3):195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lo MC, Aulabaugh A, Jin G, Cowling R, Bard J, Malamas M, Ellestad G. Evaluation of fluorescence-based thermal shift assays for hit identification in drug discovery. Anal Biochem. 2004;332(1):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]