Abstract

The inverse relationship between osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells has been linked to overall bone mass. It has previously been reported that conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) inhibits adipogenesis via a peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) mediated mechanism, while it increases osteoblastogenesis via a PPARγ-independent mechanism in mesenchymal stem cells. This suggests potential implication of CLA on improving bone mass. Thus the purpose of this study was to determine involvement of CLA on regulation of osteoblastogenesis in murine mesenchymal stem cells by focusing on the Mothers against decapentaplegic (MAD)-related family of molecules 8 (SMAD8), one of key regulators of osteoblastogenesis. The trans-10,cis-12 CLA, but not the cis-9,trans-11, significantly increased osteoblastogenesis via SMAD8, and inhibited adipogenesis independent of SMAD8, while inhibiting factors regulating osteoclastogenesis in this model. These suggest that CLA may help improve osteoblastogenesis via a SMAD8 mediated mechanism.

Keywords: CLA; trans-10,cis-12 CLA; cis-9, trans-11 CLA; osteoblastogenesis; adipogenesis

1. Introduction

Bone is a tissue undergoing continuous formation and resorption processes and the balance between these two determines overall bone mass (Mackie, 2003; Seeman, 2003). Imbalance of these two processes, particularly limited bone formation and/or excessive bone resorption, can result in osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is considered to be a silent disease with a slow progress over 10–20 years, with the primary concern being increased susceptibility to fracture (Ammann & Rizzoli, 2003). An estimated 9 million people in the US suffer from osteoporosis, and it is considered to be one of the major health concerns for the elderly (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2005). With limited success and/or adverse effects of treatment for osteoporosis, building strong bones is still considered to be one of the best preventive strategies to address osteoporosis concerns.

One approach to control osteoporosis is to modulate bone marrow stem cell differentiation. It is based on the fact that both osteoblasts (primary bone forming cells) and bone marrow adipocytes are derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), while osteoclasts (bone resorbing cells) are derived from haemotopoietic stem cells (Kronenberg, 2003; Pittenger et al., 1999). Although these cells may be differentiated into a number of different cell types, including chondrocytes or myoblasts, based on the observation that there is an inverse correlation between osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells, any bioactive components acting against differentiation of bone adipocytes may offer an opportunity resulting in increased bone mass (Kronenberg, 2003; Nelson-Dooley, Della-Fera, Hamrick & Baile, 2005; Pittenger et al., 1999).

One dietary component that has a potential role in favoring osteoblasts over adipocytes is conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). CLA was first identified as an anti-cancer component from ground beef in the 1980s (Dilzer & Park, 2012; Park & Pariza, 2007). Since then, dietary CLA has been shown to have a number of biologically beneficial effects, including modulation of immune responses, reduction of atherosclerotic development, promotion of animal growth, and modulation of body composition such as reduction of body fat along with improvement of bone mass (Dilzer & Park, 2012; Park & Pariza, 2007). Previous animal studies suggest that CLA improves overall bone mass when total body fat was significantly reduced in vivo, including both growing and adult mice (Banu et al., 2006; Berge, Ruyter & Asgard, 2004; Park et al., 1997; Park et al., 1999b; Park, Terk & Park, 2011; Rahman, Bhattacharya, Banu & Fernandes, 2007; Watkins et al., 1997). In addition, CLA significantly reduces bone marrow adipogenesis while improving osteoblastogenesis (Halade, Rahman, Williams & Fernandes, 2011; Park & Pariza, 2007; Park, Pariza & Park, 2008; Park et al., 1997; Rahman, Halade, Williams & Fernandes, 2011). These results suggest great potential of CLA on influencing MSC balances by reducing adipocytes and increasing osteoblasts, resulting in improved bone formation.

Previously it was suggested that peroxisome-proliferator activated receptor- γ (PPARγ) is one of CLA’s primary molecular targets in adipocytes (Dilzer & Park, 2012). PPARγ is one of the key mediators of adipogenesis, but more importantly PPARγ not only activates adipogenesis but also directly inhibits osteoblastogenesis in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (Akune et al., 2004; Takada, Suzawa, Matsumoto & Kato, 2007). Since CLA, particularly the trans-10,cis-12 isomer, has previously been shown to inhibit adipogenesis via PPARγ, this effect by CLA may directly contribute to its role in mesenchymal stem cell osteoblastogenesis (Brown et al., 2003; Granlund, Juvet, Pedersen & Nebb, 2003). In fact, we have previously shown that the same CLA isomer inhibits adipocyte differentiation in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via PPARγ mediated mechanisms. However, we also found that CLA promoted osteoblastogenesis via a PPARγ independent pathway in the same model (Kim, Park, Lee & Park, 2013). Thus, the goal of this research was to identify the molecular target of CLA, independent of PPARγ, for promoting osteoblastogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells.

As a potential CLA target in osteoblastogenesis, we focused on MAD-related family of molecules (SMAD8, MADH6, or SMAD9). SMADs are downstream targets for bone morphogenic proteins (BMP), members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, which regulate a number of cells including osteoblastic differentiation and bone formation (Katagiri et al., 1994; Wozney & Rosen, 1998). BMP-signals phosphorylate the receptor-SMAD (SMAD1, SMAD5, and SMAD8) and subsequently it binds to co-SMAD (SMAD4) in the cytoplasm. Then this moiety enters into the nucleus interacting with DNA binding elements and other transcriptional factors including osteoblastogenesis factors (Hill, 2009; Massague, Seoane & Wotton, 2005). Thus, SMADs are key mediators of osteoblastogenesis as shown by inhibition of SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation preventing ectopic bone formation in vivo (Arnold et al., 2006). With an inverse correlation between adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells, one can speculate the potential role of osteoblastogenic mediators (such as SMAD8) influencing adipogenesis similar to PPARγ (Binato et al., 2006; Li, 2008). However, contrary to PPARγ directly inhibiting osteogenesis, there is a lack of information for supporting the roles of SMADs, particularly SMAD8, in adipogenesis. Thus, we determined the contribution of SMAD8 to adipogenesis as well as the mechanism of CLA on SMAD8 for improvement of osteoblastogenesis by using a SMAD8 knock-down mesenchymal stem cell model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), D1 ORL UVA (CRL-12424), were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The purity of linoleic acid was 99% (Nu-Chek Prep, Inc., Elysian, MN, USA). The trans-10,cis-12 CLA, cis-9,trans-11 CLA, and CLA mixed isomer (CLA-mix) were provided by Natural Lipids (Hovdebygda, Norway). The trans-10,cis-12 CLA preparation was 94 % pure, with 2% cis-9,trans-11 isomer and 3% other conjugated linoleic acid isomers. The cis-9,trans-11 CLA preparation was 90% pure, with 4% trans-10,cis-12 isomer, 2% other conjugated linoleic acid isomers, and 3% oleic acid. The purity of CLA mixed isomer (CLA-mix) was 80.7% CLA (37.8% cis-9,trans-11, 37.6% trans-10,cis-12, and 5.3% other isomers), 13.7% oleic acid, 3.2% stearic acid, 0.4% palmitic acid and 0.2% linoleic acid. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and penicillin/streptomycin mixture were purchased from Mediatech (Manassas, VA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), bovine serum albumin (BSA), Puromycin®, and other chemicals needed were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). RNA interference small hairpin (sh) RNA plasmids targeting for SMAD8 (Suresilence®) were from SA biosciences (Frederick, MD, USA).

2.2. Cell Culture

Mouse mesenchymal cells were routinely maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics (100 U penicillin G and 100 μg /mL streptomycin) in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37 °C and subcultured after 70–80% confluence. SMAD8 knock-down was achieved by transfection of plasmids encoding shRNA sequences to SMAD8 (Suresilence®, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using Lipofectamine® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids contained Puromycin® antibiotic resistance gene and stable shRNA expressing clones were selected by incubating with DMEM containing 10% FBS, antibiotics, and Puromycin®. Knock-down of SMAD8 in selected stable shRNA expressing clones were tested by qRT-PCR (StepOne Plus™ Real-Time PCR system, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Fatty acids were treated as fatty acid-albumin complexes prepared to contain a 1:1 molar ratio for linoleic acid, cis-9,trans-11 CLA, and trans-10,cis-12 CLA and 2:1 ratio for CLA-mix as described previously (Park et al., 1997). Fatty-acid complexes were added to media as 50 μM for individual fatty acids and albumin, and 100 μM for CLA-mix. The concentrations used were selected based on previous publication reporting serum levels of CLA ranged from 23–150 μM when 0.5% CLA was fed to rats for 4 weeks and the plasma concentrations of CLA in humans after taking 0.8–3.2 g CLA/day for 2 months ranged from 50–200 μM (Mele et al., 2013; Park et al., 1997).

2.3. Osteoblastogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSC)

2.3.1. Induction of osteoblastogenesis

Cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2. At confluence (designated as “Day 0”), osteoblastogenic differentiation was initiated by supplementation of 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 50 μM ascorbic acid, and 0.1 μM dexamethasone in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Differentiation was continued for 28 days with changing media every other day. Fatty acid-albumin complexes were added to culture medium starting at Day 0.

2.3.2. DNA fragmentation analysis

After 28 days of differentiation, cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), collected in 500 μL of lysis buffer (pH 8.0, 10mM Tris-HCl, 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% Triton X-100) by scraping, and kept at −70°C until analysis. After homogenization, cells were centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min to separate fragmented and genomic DNA. Fragmented DNA in supernatant was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v/v), and then precipitated by using polyacryl carrier (Molecular Probes, INC., Eugene, OR, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was extracted with DNAzol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) from the pellet according to manufacturer’s instruction. Quantification of fragmented and genomic DNA was conducted using the fluorescent PicoGreen assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Percentage of DNA fragmentation was calculated as fragmented DNA / (fragmented DNA + Genomic DNA) × 100.

2.3.3. Calcium quantification

After 28 days of treatment, the cells were washed twice with PBS, incubated with 0.5 M HCl overnight at room temperature on an orbital shaker, and collected by scraping. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min and the supernatants were used to determine calcium by Calcium-O-Cresolphthalein Complexone Method (Hillel, 1967). The protein concentration was measured using the Bio-Rad DC protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The amount of calcium was normalized to its protein concentration.

2.3.4. RNA isolation and Real-time PCR

At the end of differentiation (28 days), the cells were washed twice with cold PBS, and total RNA fraction was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA were subjected to cDNA synthesis using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted with TaqMan® gene expression assays (alkaline phosphatase; Mm00475834_m1, osteocalcin; Mm03413826_mH, RUNX2; Mm00501584-m1, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Mm99999915_g1) was used as an internal standard.

2.3.5. Alkaline phosphatase activity

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was measured according to Mizutani et al. (2001). Briefly, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, incubated for 30 minutes at 4 °C with assay buffer (pH 9.0, 1.5 M Tris-HCl, 1mM ZnCl2, 1mM MgCl2, and 1% Triton X-100) and collected by scraping. To collect the supernatants, cell lysates were centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Supernatants were used to determine ALP activity and protein concentration. To determine ALP activity, 50 μL of supernatant was placed into 96 well microtiter plate, 150 μL of substrate solution (pH 10.0, 7.6 mM 4-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate, 100 mM Tris-HCl, and 10 mM MgCl2) was added and then incubated exactly 1 hour at 37 °C. Reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of 3M NaOH. Absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) at 410 nm. The standard curve was generated using p-nitrophenol at concentrations from 0 to 106 μmol/mL. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bio-Rad protein DC assay kit with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The ALP activity was expressed as production of p-nitrophenol (nmol) formed per minute per milligrams of protein.

2.3.6. Determination of soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (sRANKL) and osteoclast inhibiting factor (OCIF) secretion from osteoblasts

ELISA kits from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used to determine the concentration of soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (sRANKL) and osteoclast inhibiting factor (OCIF) in culture media according to manufacturer’s instruction. Protein concentration of media was determined with using Bio-Rad protein DC assay kit with bovine serum albumin as a standard, and concentration was normalized with protein concentration.

2.4. Adipogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

2.4.1. Induction of adipogenesis

Cells were seeded at a density of 4.8×104 cells /well in 6 well plates. The media was changed every two days. After confluence, cells were incubated two more days (designated as “Day 0”), the cells were differentiated into adipocytes by incubating in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics supplemented with 1 μM dexamethasone, 1 mM methyl-isobutylxanthine, and 5 μg/mL porcine insulin. After 2 days (Day 2), the media was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics, supplemented with insulin (5 μg/mL) alone and incubated 2 more days. After Day 4, the media was switched to DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics and incubated until Day 8. The cells were treated with fatty acid-albumin complexes in culture medium starting at Day 0.

2.4.2. Triacylglycerol (TG) analysis, RNA isolation and PCR

At the end of differentiation (day 8), cells were carefully washed twice with PBS, collected by scraping in PBS containing 1% Triton-X, and sonicated to obtain homogenous samples. Samples were centrifuged at 500g for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant were used to measure the TG and protein concentration using colorimetric assay kits (Genzyme Diagnostics, Charlottetown, PE, Canada and Bio-Rad protein DC assay kit, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). TG content was normalized with protein concentration. Total RNA was prepared and analyzed as described in an earlier section. Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted with TaqMan® gene expression assays (PPARγ ; Mm00440940_m1, fatty acid synthase; Mm00662291_g1, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as in internal standard.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± S.E. values and analyzed using the analysis of variance procedure (ANOVA) of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significant differences between treatment means were determined using Duncan’s multiple-range tests. Significance of differences was defined at the p<0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of SMAD8 Knock-Down bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (SMAD8 KD MSC)

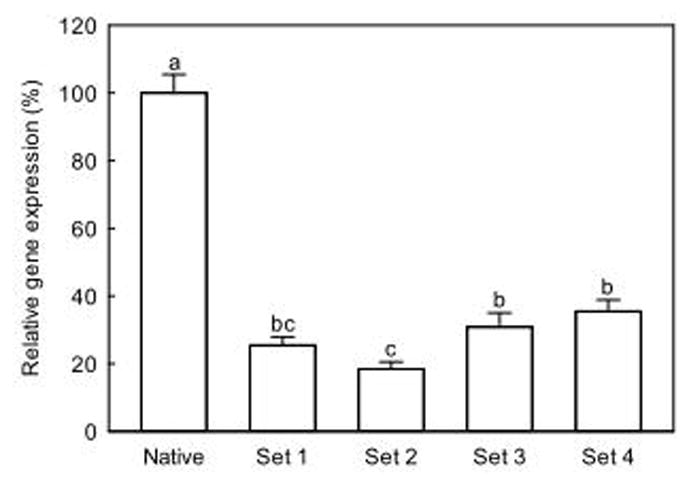

SMAD8 knock-down (KD) efficiency of shRNA is presented in Figure 1. All shRNA expressing clones showed reduced SMAD8 expression compared to native cells. shRNA set 2 effectively inhibited SMAD8 expression, displaying only 18% of the expression of native cells. These cells were used for further experiments.

Figure 1.

SMAD8 gene expression of shRNA transfected mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Values are mean ± SE (n=4). Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05.

3.2. Effects of CLAs on osteoblastogenesis

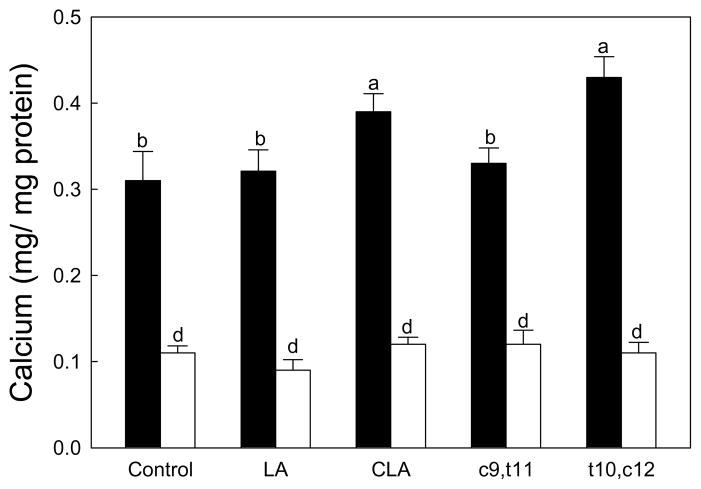

We first determined the calcium deposition in the native and SMAD8 KD MSC differentiated into osteoblasts (Figure 2). Defragmented DNA was measured to determine the apoptotic effects of CLAs and there were no difference in defragmentation of DNA in all treatments (data not shown). This confirms that any effects seen in our results were not mediated by apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Effects of CLA on the calcium deposition in mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into osteoblasts. Native mouse mesenchymal stem cells (▬) and SMAD8 knock-down cells (▭). Values are mean ± SE (n=6). Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, mixture of cis-9, trans-11 and cis-10, cis-12 isomers; c9,t11, cis-9, trans-11 CLA; t10,c12, trans-10, cis-12 CLA.

As expected, SMAD8 KD MSC deposited less calcium compared to native cells (Figure 2 between two control treatments). In native cells, calcium deposition was increased by CLA-mix and the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer compared to BSA control, while linoleic acid and the cis-9,trans-11 CLA did not influence calcium deposit compared to the control (Fig. 2). The increase of calcium by CLA-mix and the trans-10,cis-12 CLA were 24 and 38% compared to the control, respectively (p<0.05). In SMAD8 KD MSC, there was no significant difference in calcium deposition in all treatments (Fig. 2, white bars). These results suggest a significant role of SMAD8 in calcium deposition. In addition, these data imply the effects of CLA, particularly the trans-10,cis-12 isomer, on increased calcium deposition requires SMAD8.

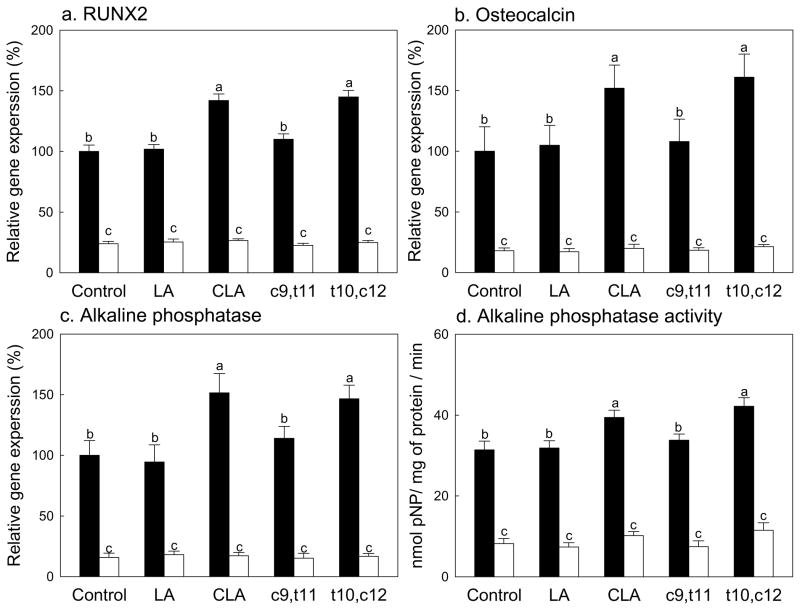

To confirm this further, key regulators of osteoblastogenesis, expressions of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) and osteocalcin and expression and activities of alkaline phosphatase, were measured in this model (Fig. 3). RUNX2 is a transcriptional factor belonging to the runt-domain gene family. It plays a significant role in osteoblastogenesis by inducing ALP activity and expression of bone matrix protein genes, as well as mineralization in immature mesenchymal cells and osteoblastic cells (Harada et al., 1999; Komori et al., 1997). ALP is an enzyme that hydrolyzes phosphate esters, which can provide inorganic phosphate for mineralization and the expression of ALP occurring at the early stage of osteoblastic differentiation (Owen et al., 1990; Whyte, 2010). Lastly, osteocalcin is another important osteoblastogenic marker and it is expressed during the late developmental stage, during the mineralization period, of bone formation (Gerstenfeld, Chipman, Glowacki & Lian, 1987; Pan & Price, 1985). In native cells, supplementation of either linoleic acid or the cis-9,trans-11 CLA did not significantly influence any of these osteoblastic markers compared to control (Fig. 3). CLA-mix and the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomers significantly increased expressions of RUNX2, osteocalcin, and alkaline phosphatase and activities of alkaline phosphatase compared to control. As expected, SMAD8 KD MSC had significantly reduced expressions of RUNX2, osteocalcin, and ALP and activities of ALP compared to native cells (Fig. 3A–3D). However, there were no effects of any of treatment on these parameters in SMAD8 KD MSC (Fig. 3). This confirms that these osteoblastogenesis markers need SMAD8 and the effects of CLA, particularly the trans-10,cis-12 isomer, on osteoblastogenesis are mediated via SMAD8.

Figure 3.

Effects of CLA on the expressions of osteoblastogenic markers, RUNX2 (a) and osteocalcin (b), and expressions (c) and activity (d) of alkaline phosphatase in mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into osteoblasts. Native mouse mesenchymal stem cells (▬) and SMAD8 knock-down cells (▭). Values are mean ± SE (n=6). Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, mixture of cis-9, trans-11 and cis-10, cis-12 isomers; c9,t11, cis-9, trans-11 CLA; t10,c12, trans-10, cis-12 CLA.

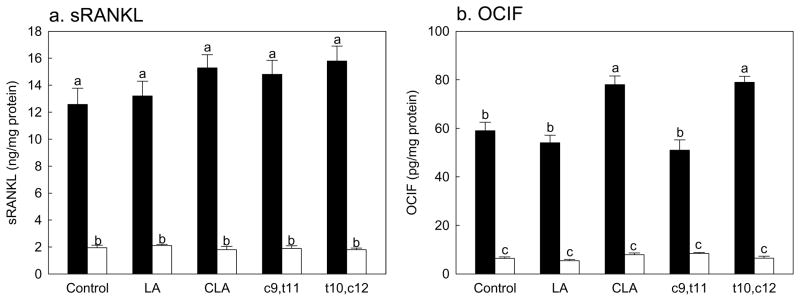

We further determined the effects of CLA on expression of sRANKL and OCIF. These are two important regulators of osteoclasts; sRANKL is an activator of osteoclastogenesis and OCIF is a decoy receptor for sRANKL (Suda et al., 1999). Expressions of sRNAKL and OCIF in SMAD8 KD MSC were significantly reduced compared to those of native cells as expected (Fig. 4A & 4B). There were no effects of any fatty acids on the expressions of sRANKL in both native and SMAD8 KD MSC (Fig. 4A). The expression of OCIF was increased by CLA-mix and the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer compared to controls, while linoleic acid or the cis-9,trans-11 CLA had no effect (Fig. 4B). This difference, increased OCIF by the trans-10,cis-12 CLA, was not observed in SMAD8 KD MSC. These data suggest that the trans-10,cis-12 CLA may reduce osteoclastogenesis by increasing OCIF, but not by modulating sRANKL.

Figure 4.

Effects of CLA on the sRANKL (a) and OCIF (b) production in mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into osteoblasts. Native mouse mesenchymal stem cells (▬) and SMAD8 knock-down cells (▭). Values are mean ± SE (n=6). Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, mixture of cis-9, trans-11 and cis-10, cis-12 isomers; c9,t11, cis-9, trans-11 CLA; t10,c12, trans-10, cis-12 CLA.

3.3. Effects of CLAs on adipogenesis

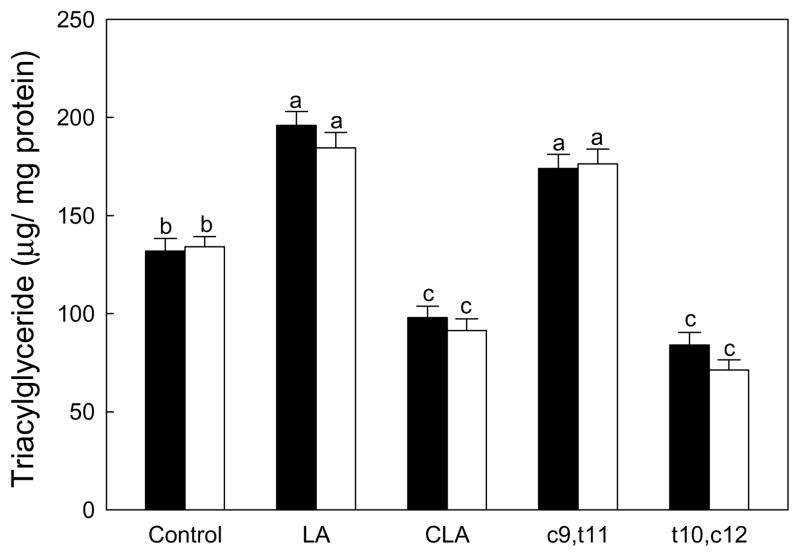

To determine the potential role of SMAD8 on adipogenesis, we also determined TG accumulation and expressions of key adipogenic markers. No differences in overall TG deposition were observed between native and SMAD8 KD MSC (Fig. 5). This suggests that SMAD8 may not directly influence adipogenesis, unlike PPARγ, which suppresses osteoblastogenesis (Akune et al., 2004; Kim, Park, Lee & Park, 2013).

Figure 5.

Effects of CLA on the triglyceride deposition in mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into osteoblasts. Native mouse mesenchymal stem cells (▬) and SMAD8 knock- down cells (▭). Values are mean ± SE (n=6). Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, mixture of cis-9, trans-11 and cis-10, cis-12 isomers; c9,t11, cis-9, trans-11 CLA; t10,c12, trans-10, cis-12 CLA.

TG deposition was increased by linoleic acid and the cis-9,trans-11 CLA isomer, while significantly reduced by CLA-mix and the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer compared to BSA control in native mesenchymal stem cells (Fig. 5). However, there were no significant differences in TG accumulation between native and SMAD8 KD MSC in all fatty acid treatments. This again suggests that adipogenesis was not influenced by SMAD8 in this model.

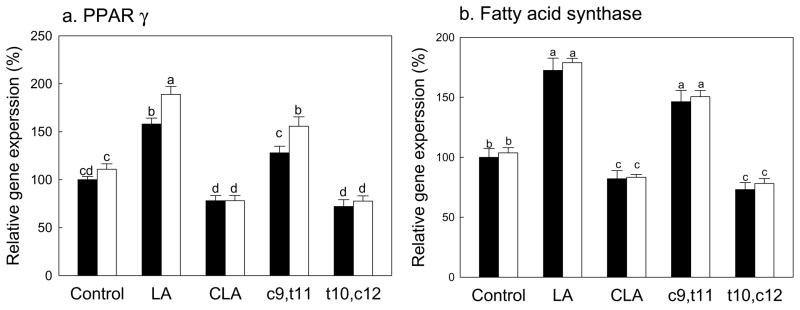

We further determined the expressions of PPARγ, the key regulator of adipogenesis, and fatty acid synthase (FAS), one of downstream targets for PPARγ and one of the key enzymes for lipogenesis (Fig. 6A & 6B). Consistent with results in Figure 5, no differences in PPARγ and FAS expressions were observed between native and SMAD8 KD MSC. As expected from TG data in Figure 5, both linoleic acid and the cis-9,trans-11 CLA significantly increased expressions of PPARγ and FAS compared to BSA control in both native and SMAD8 KD MSC. CLA-mix and the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer significantly reduced these markers compared to control, linoleic acid and the cis-9,trans-11 CLA in both native and SMAD8 KD MSC. These results further confirm that SMAD8 did not contribute to adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells.

Figure 6.

Effects of CLA on the PPARγ (a) and fatty acid synthase (b) gene expression in mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into adipocytes. Native mouse mesenchymal stem cells (▬) and SMAD8 knock-down cells (▭). Values are mean ± SE (n=6). Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05. LA, linoleic acid; CLA, mixture of cis-9, trans-11 and cis-10, cis-12 isomers; c9,t11, cis-9, trans-11 CLA; t10,c12, trans-10, cis-12 CLA.

4. Discussion

Based on the previous observation that CLA inhibits adipogenesis, including adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells, we further examined CLA’s molecular target on osteoblastogenesis (Kim, Park, Lee & Park, 2013; Platt & El-Sohemy, 2009). Results of these current studies suggest that SMAD8 plays a role in CLA’s effect on osteoblastogenesis. This was positively associated with the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer, but not the cis-9,trans-11 isomer, which is consistent with previous publications that the trans-10,cis-12 CLA is the active isomer for inhibition of adipogenesis (Park & Pariza, 2007; Park et al., 1999b). This is the first report that SMAD8 mediates effects of the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer on osteoblastogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells. Additionally, due to the inverse correlation of differentiation between adipocytes and osteoblasts in mesenchymal stem cells, inhibiting SMAD8 may influence adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells, as PPARγ does to osteoblastogenesis. However, we did not observe any differences of adipogenesis between native and SMAD8 KD MSC. This suggests no involvement of SMAD8 in adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells.

In addition to involvement of SMAD8, CLA may enhance osteoblastogenesis via different mechanisms, such as other SMADs or Wnt10b (Lee et al., 2000; Platt & El-Sohemy, 2009). Since BMP signals through heterodimers of SMADs (SMAD 1, 4, 5 and 8), other SMADs may also have significantly influence, as does SMAD8 (Lee et al., 2000). Meanwhile, Wnt signal involves complex interactions among various proteins and activation of Wnt1, Wnt2, and Wnt3a induced alkaline phosphatase (ALP), an early osteoblastogenic marker, in C2C12, C3H10T1/2, and ST2 cell lines (Pandur, Maurus & Kuhl, 2002; Rawadi, 2008). It is supported by observations of increasing bone volume and strength as well as more trabecular bone in transgenic mouse over-expressing Wnt10b and decreasing bone and fewer trabecular bone mass in Wnt10b-deficient mice (Bennett et al., 2005; Bennett et al., 2007). Interestingly, it is reported that there is crosstalk between BMP and Wnt signaling pathways to osteoblast maturation, such as synergetic osteoblastogenic effects of β-catenin and BMP2 via Lef/Tcf dependent mechanisms (Giese, Pagel & Grosschedl, 1997; Mbalaviele et al., 2005). In fact, Platt et al. (2009) reported that the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer potentiates Wnt10b signaling by stabilization of β-catenin resulting in increased human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Thus we cannot exclude the possibility that the trans-10,cis-12 CLA may contribute to Wnt10b signaling to improve osteoblastogenesis in this model as well.

Overall bone mass is a balance between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic bone resorption. The mesenchymal stem cell model used here is rather limited to osteoblasts, however, mesenchymal stem cells can contribute to bone resorption by regulators for osteoclasts via sRANKL and OCIF (Boyle, Simonet & Lacey, 2003; Martin & Ng, 1994; Suda et al., 1999). Our results showed that trans-10,cis-12 CLA significantly increased OCIF expression, which suggests inhibition of osteoclastogenesis by interfering binding of sRANKL to its ligand RANK (Suda et al., 1999). We did not observe any direct effects of CLA on sRANKL in this model. However, others reported that the trans-10,cis-12 CLA significantly reduced sRANKL in in vivo and macrophage cell models (Rahman, Bhattacharya & Fernandes, 2006; Rahman, Halade, Williams & Fernandes, 2011). The differences may be due to in part to different models used, mesenchymal vs. macrophage cell lineage, and in vitro vs. in vivo, where there are other contributing factors for osteoclastogenesis. In addition, physical activity is a well-known positive factor for bone health, in particular CLA has been reported to improve exercise-associated outcome in mice and humans (Dilzer & Park, 2012; Kim, Kim & Park, 2012; Park & Park, 2012). It is possible that CLA may exert its effects on bone mass by activity-mediated mechanisms in addition to its role described in this report (Iwamoto, Sato, Takeda & Matsumoto, 2009; Pigozzi et al., 2009; Wolff et al., 1999).

Currently there are a limited number of publications with regard to CLA and bone health in humans and the overall results were not consistent (Brownbill, Petrosian & Ilich, 2005; Dilzer & Park, 2012; Kreider et al., 2002). In animal studies, it was reported that CLA feeding resulted in increased cancellous and cortical bone mineral content or bone mineral density with exercise in mice, however, others reported no effects by CLA on these markers (Banu et al., 2006; Banu, Bhattacharya, Rahman & Fernandes, 2008; Burr, Taylor & Weiler, 2006; Rahman, Bhattacharya, Banu & Fernandes, 2007; Roy et al., 2008; Weiler, Fitzpatrick & Fitzpatrick-Wong, 2008). The relatively small differences caused by CLA, although significant, may have contributed to this inconsistency. In addition, it has been suggested that dietary levels of calcium may enhance its effects on bone mass, particularly with young animals, suggesting a potential role of CLA in bone development (Park, Terk & Park, 2011). When aged animals were tested, CLA supplementation significantly improved bone mass accompanied with reduced bone marrow adiposity and decreased bone resorption (Halade, Rahman, Williams & Fernandes, 2011; Park & Park, 2010; Rahman, Halade, Williams & Fernandes, 2011). These results suggest that CLA not only influences bone formation consistent with our current results, but also influences bone resorption. Thus, the possibility that CLA regulates osteoclastogenesis independent of osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis cannot be ruled out.

Among human studies, Kreider et al. (2002) and Brownbill et al. (2005) reported beneficial effects of CLA on bone mass, while others observed no benefit of CLA on bone health (Dilzer & Park, 2012). It is speculated that the inconsistent results on bone health due to CLA in humans compared to animals may be due in part to differences in metabolism between species, or various CLA doses, isomers, and duration of studies used (Dilzer & Park, 2012; Park & Pariza, 2007; Terpstra, 2001). Further clinical studies are needed to confirm the role of CLA in bone health, particularly on involvement of adipogenesis and osteoblastogenesis from mesenchymal stem cells.

Among the two major CLA isomers, the cis-9,trans-11 isomer occurs naturally and is the predominant CLA isomer found in foods (Chin, Storkson, Ha & Pariza, 1992). The estimated average intake of CLA, primarily the cis-9,trans-11 isomer, for Americans from natural sources is in a range of 15 to 137 mg CLA per day with subgroups of high dairy diet consuming approximately 300 mg CLA per day (Herbel, McGuire, McGuire & Shultz, 1998; Park et al., 1999a; Ritzenthaler et al., 1998). By contrast, the trans-10,cis-12 isomer is a relatively minor component in foods but found significantly in synthetically prepared CLA, approximately 35–45% along with about 35–45% of the cis-9,trans-11 isomer as in CLA-mixture used in this study. Results from the current study primarily indicate a role of the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer in osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells. However, benefit of dietary CLA (mainly the cis-9,trans-11) with regard to bone mineral density in postmenopausal women has been previously reported (Brownbill, Petrosian & Ilich, 2005). In addition, a role for the cis-9,trans-11 CLA isomer in calcium absorption has been reported along with trans-10,cis-12 CLA (Brownbill, Petrosian & Ilich, 2005; Jewell, Cusack & Cashman, 2005; Kelly, Cusack, Jewell & Cashman, 2003; Roche et al., 2001). Based on this information, we cannot rule out the potential role of the cis-9,trans-11 isomer in bone health.

Currently it is not completely clear how the CLA isomers exert their effects. Previously it was reported that CLA isomers bind to PPARγ directly, where the cis-9,trans-11 isomer was slightly more effective on binding/activation of PPARγ than the trans-10,cis-12 CLA (Belury & Vanden Heuvel, 1999). Others suggested that the trans-10,cis-12 CLA, but not cis-9,trans-11, may have direct interaction on enzyme as shown by inhibition of steaoryl-CoA desaturase (Park et al., 2000). Thus it is likely interaction of CLA isomers on certain binding site(s) may have been involved in their activity and further studies are needed to confirm this.

In summary, the trans-10,cis-12 CLA isomer significantly improves bone formation by promoting osteoblastogenesis and inhibiting adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells, while simultaneously inhibiting osteoclastogenesis. The effects of the trans-10,cis-12 CLA on osteoblastogenesis is mediated by a SMAD8 mediated pathway. However, suppressed adipogenesis by trans-10,cis-12 CLA treatment is independent of its role in inhibition of SMAD8 pathway. In addition, the trans-10,cis-12 CLA reduces factors known to promote osteoclast SMAD8 mediated pathway, thus contributing to overall improvement of bone health. Although our results are limited to in vitro models and relatively small improvement, results from this study may provide information for the application of CLA for bone health, particularly for those at risk of developing osteoporosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Jayne M. Storkson for assistance with manuscript preparation. This work was supported by NIH grants, 1R21AT004456 and 3R21AT004456-02S1. Dr. Yeonhwa Park is one of the inventors of CLA use patents that are assigned to the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akune T, Ohba S, Kamekura S, Yamaguchi M, Chung UI, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Nakamura K, Kadowaki T, Kawaguchi H. PPARgamma insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:846–855. doi: 10.1172/JCI19900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammann P, Rizzoli R. Bone strength and its determinants. Osteoporosis International : A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2003;14(Suppl 3):S13–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SJ, Maretto S, Islam A, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ. Dose-dependent Smad1, Smad5 and Smad8 signaling in the early mouse embryo. Developmental Biology. 2006;296:104–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banu J, Bhattacharya A, Rahman M, Fernandes G. Beneficial effects of conjugated linoleic acid and exercise on bone of middle-aged female mice. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2008;26:436–445. doi: 10.1007/s00774-008-0863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banu J, Bhattacharya A, Rahman M, O’Shea M, Fernandes G. Effects of conjugated linoleic acid and exercise on bone mass in young male Balb/C mice. Lipids in Health and Disease [Electronic Resource] 2006;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belury MA, Vanden Heuvel JP. Advances in Conjugated Linoleic Acid Resarch. In: Yurawecz MP, Mossoba MM, Kramer JKG, Pariza MW, Nelson GJ, editors. Chapter 32. Modulation of Diabetes by Conjugated Linoleic Acid. Vol. 1. Champaign: AOCS Press; 1999. pp. 404–411. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CN, Longo KA, Wright WS, Suva LJ, Lane TF, Hankenson KD, MacDougald OA. Regulation of osteoblastogenesis and bone mass by Wnt10b. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:3324–3329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408742102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CN, Ouyang H, Ma YL, Zeng Q, Gerin I, Sousa KM, Lane TF, Krishnan V, Hankenson KD, MacDougald OA. Wnt10b increases postnatal bone formation by enhancing osteoblast differentiation. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research : The Official Journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22:1924–1932. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge GM, Ruyter B, Asgard T. Conjugated linoleic acid in diets for juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar); effects on fish performance, proximate composition, fatty acid and mineral content. Aquaculture. 2004;237:365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Binato R, Alvarez Martinez CE, Pizzatti L, Robert B, Abdelhay E. SMAD 8 binding to mice Msx1 basal promoter is required for transcriptional activation. The Biochemical Journal. 2006;393:141–150. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Boysen MS, Jensen SS, Morrison RF, Storkson J, Lea-Currie R, Pariza M, Mandrup S, McIntosh MK. Isomer-specific regulation of metabolism and PPARgamma signaling by CLA in human preadipocytes. Journal of Lipid Research. 2003;44:1287–1300. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300001-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownbill RA, Petrosian M, Ilich JZ. Association between dietary conjugated linoleic acid and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2005;24:177–181. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr LL, Taylor CG, Weiler HA. Dietary conjugated linoleic acid does not adversely affect bone mass in obese fa/fa or lean Zucker rats. Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood, NJ) 2006;231:1602–1609. doi: 10.1177/153537020623101004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin SF, Storkson JM, Ha YL, Pariza MW. Dietary sources of conjugated dienoic isomers of linoleic acid. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 1992;5:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dilzer A, Park Y. Implication of Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) in Human Health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2012;52:488–513. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2010.501409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstenfeld LC, Chipman SD, Glowacki J, Lian JB. Expression of differentiated function by mineralizing cultures of chicken osteoblasts. Developmental Biology. 1987;122:49–60. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese K, Pagel J, Grosschedl R. Functional analysis of DNA bending and unwinding by the high mobility group domain of LEF-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:12845–12850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granlund L, Juvet LK, Pedersen JI, Nebb HI. Trans10, cis12-conjugated linoleic acid prevents triacylglycerol accumulation in adipocytes by acting as a PPARgamma modulator. Journal of Lipid Research. 2003;44:1441–1452. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300120-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halade GV, Rahman MM, Williams PJ, Fernandes G. Combination of conjugated linoleic acid with fish oil prevents age-associated bone marrow adiposity in C57Bl/6J mice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2011;22:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Tagashira S, Fujiwara M, Ogawa S, Katsumata T, Yamaguchi A, Komori T, Nakatsuka M. Cbfa1 isoforms exert functional differences in osteoblast differentiation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:6972–6978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbel BK, McGuire MK, McGuire MA, Shultz TD. Safflower oil consumption does not increase plasma conjugated linoleic acid concentrations in humans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;67:332–337. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CS. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Smad proteins. Cell Research. 2009;19:36–46. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillel JG. An improved automated procedure for the determination of calcium in biological specimens. Analytical Biochemistry. 1967;18:521–531. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto J, Sato Y, Takeda T, Matsumoto H. Role of sport and exercise in the maintenance of female bone health. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2009;27:530–537. doi: 10.1007/s00774-009-0066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewell C, Cusack S, Cashman KD. The effect of conjugated linoleic acid on transepithelial calcium transport and mediators of paracellular permeability in human intestinal-like Caco-2 cells. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids. 2005;72:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri T, Yamaguchi A, Komaki M, Abe E, Takahashi N, Ikeda T, Rosen V, Wozney JM, Fujisawa-Sehara A, Suda T. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 converts the differentiation pathway of C2C12 myoblasts into the osteoblast lineage. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;127:1755–1766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly O, Cusack S, Jewell C, Cashman KD. The effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids, including conjugated linoleic acid, on calcium absorption and bone metabolism and composition in young growing rats. The British Journal of Nutrition. 2003;90:743–750. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Park Y, Lee SH, Park Y. trans-10,cis-12 Conjugated linoleic acid promotes bone formation by inhibiting adipogenesis by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma-dependent mechanisms and by directly enhancing osteoblastogenesis from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2013;24:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kim J, Park Y. Trans-10,cis-12 Conjugated Linoleic Acid Enhances Endurance Capacity by Increasing Fatty Acid Oxidation and Reducing Glycogen Utilization in Mice. Lipids. 2012;47:855–863. doi: 10.1007/s11745-012-3698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RB, Ferreira MP, Greenwood M, Wilson M, Almada AL. Effects of conjugated linoleic acid supplementation during resistance training on body composition, bone density, strength, and selected hematological markers. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2002;16:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423:332–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Kim HJ, Li QL, Chi XZ, Ueta C, Komori T, Wozney JM, Kim EG, Choi JY, Ryoo HM, Bae SC. Runx2 is a common target of transforming growth factor beta1 and bone morphogenetic protein 2, and cooperation between Runx2 and Smad5 induces osteoblast-specific gene expression in the pluripotent mesenchymal precursor cell line C2C12. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20:8783–8792. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.8783-8792.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B. Bone morphogenetic protein-Smad pathway as drug targets for osteoporosis and cancer therapy. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets. 2008;8:208–219. doi: 10.2174/187153008785700127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie EJ. Osteoblasts: novel roles in orchestration of skeletal architecture. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2003;35:1301–1305. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Ng KW. Mechanisms by which cells of the osteoblast lineage control osteoclast formation and activity. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1994;56:357–366. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes & Development. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbalaviele G, Sheikh S, Stains JP, Salazar VS, Cheng SL, Chen D, Civitelli R. Beta-catenin and BMP-2 synergize to promote osteoblast differentiation and new bone formation. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2005;94:403–418. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele MC, Cannelli G, Carta G, Cordeddu L, Melis MP, Murru E, Stanton C, Banni S. Metabolism of c9,t11-conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) in humans. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids. 2013;89:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani A, Sugiyama I, Kuno E, Matsunaga S, Tsukagoshi N. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases during ascorbate-induced differentiation of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research : The Official Journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2001;16:2043–2049. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. [accessed May 2013];Bone Health Basics: Get the Facts. 2005 http://www.nof.org/learn.

- Nelson-Dooley C, Della-Fera MA, Hamrick M, Baile CA. Novel treatments for obesity and osteoporosis: targeting apoptotic pathways in adipocytes. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;12:2215–2225. doi: 10.2174/0929867054864886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen TA, Aronow M, Shalhoub V, Barone LM, Wilming L, Tassinari MS, Kennedy MB, Pockwinse S, Lian JB, Stein GS. Progressive development of the rat osteoblast phenotype in vitro: reciprocal relationships in expression of genes associated with osteoblast proliferation and differentiation during formation of the bone extracellular matrix. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1990;143:420–430. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041430304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan LC, Price PA. The propeptide of rat bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid protein shares homology with other vitamin K-dependent protein precursors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82:6109–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandur P, Maurus D, Kuhl M. Increasingly complex: new players enter the Wnt signaling network. BioEssays : News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology. 2002;24:881–884. doi: 10.1002/bies.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Pariza MW. Mechanisms of body fat modulation by conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) Food Research International. 2007;40:311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Pariza MW, Park Y. Co-supplementation of dietary calcium and conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) improves bone mass in mice. Journal of Food Science. 2008;73:C556–C560. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Albright KJ, Liu W, Storkson JM, Cook ME, Pariza MW. Effect of conjugated linoleic acid on body composition in mice. Lipids. 1997;32:853–858. doi: 10.1007/s11745-997-0109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, McGuire MK, Behr R, McGuire MA, Evans MA, Shultz TD. High-fat dairy product consumption increases delta 9c,11t-18:2 (rumenic acid) and total lipid concentrations of human milk. Lipids. 1999a;34:543–549. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Park Y. Conjugated fatty acids increase energy expenditure in part by increasing voluntary movement in mice. Food Chem. 2012;133:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Park Y. Conjugated nonadecadienoic acid is more potent than conjugated linoleic acid on body fat reduction. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2010;21:764–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Storkson JM, Albright KJ, Liu W, Pariza MW. Evidence that the trans-10,cis-12 isomer of conjugated linoleic acid induces body composition changes in mice. Lipids. 1999b;34:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s11745-999-0358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Storkson JM, Ntambi JM, Cook ME, Sih CJ, Pariza MW. Inhibition of hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity by trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid and its derivatives. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1486:285–292. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Terk M, Park Y. Interaction between dietary conjugated linoleic acid and calcium supplementation affecting bone and fat mass. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2011;29:268–278. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigozzi F, Rizzo M, Giombini A, Parisi A, Fagnani F, Borrione P. Bone mineral density and sport: effect of physical activity. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2009;49:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt ID, El-Sohemy A. Regulation of osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation from human mesenchymal stem cells by conjugated linoleic acid. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2009;20:956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Bhattacharya A, Banu J, Fernandes G. Conjugated linoleic acid protects against age-associated bone loss in C57BL/6 female mice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2007;18:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Bhattacharya A, Fernandes G. Conjugated linoleic acid inhibits osteoclast differentiation of RAW264.7 cells by modulating RANKL signaling. Journal of Lipid Research. 2006;47:1739–1748. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600151-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Halade GV, Williams PJ, Fernandes G. t10c12-CLA maintains higher bone mineral density during aging by modulating osteoclastogenesis and bone marrow adiposity. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226:2406–2414. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawadi G. Wnt signaling and potential applications in bone diseases. Current Drug Targets. 2008;9:581–590. doi: 10.2174/138945008784911778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzenthaler K, McGuire M, Falen R, Shultz T, McGuire M. Estimation of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) intake. Faseb Journal. 1998;12:A527–A527. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche HM, Terres AM, Black IB, Gibney MJ, Kelleher D. Fatty acids and epithelial permeability: effect of conjugated linoleic acid in Caco-2 cells. Gut. 2001;48:797–802. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.6.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy BD, Bourgeois J, Rodriguez C, Payne E, Young K, Shaughnessy SG, Tarnopolosky MA. Conjugated linoleic acid prevents growth attenuation induced by corticosteroid administration and increases bone mineral content in young rats. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et Metabolisme. 2008;33:1096–1104. doi: 10.1139/H08-094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman E. Reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption: rational targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International : A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2003;14(Suppl 3):S2–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Jimi E, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocrine Reviews. 1999;20:345–357. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada I, Suzawa M, Matsumoto K, Kato S. Suppression of PPAR transactivation switches cell fate of bone marrow stem cells from adipocytes into osteoblasts. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1116:182–195. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra AH. Differences between humans and mice in efficacy of the body fat lowering effect of conjugated linoleic acid: role of metabolic rate. The Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131:2067–2068. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.7.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins BA, Shen CL, McMurtry JP, Xu H, Bain SD, Allen KG, Seifert MF. Dietary lipids modulate bone prostaglandin E2 production, insulin-like growth factor-I concentration and formation rate in chicks. The Journal of Nutrition. 1997;127:1084–1091. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.6.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler HA, Fitzpatrick S, Fitzpatrick-Wong SC. Dietary conjugated linoleic acid in the cis-9, trans-11 isoform reduces parathyroid hormone in male, but not female, rats. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2008;19:762–769. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte MP. Physiological role of alkaline phosphatase explored in hypophosphatasia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1192:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff I, van Croonenborg JJ, Kemper HC, Kostense PJ, Twisk JW. The effect of exercise training programs on bone mass: a meta-analysis of published controlled trials in pre- and postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis International : A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 1999;9:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s001980050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozney JM, Rosen V. Bone morphogenetic protein and bone morphogenetic protein gene family in bone formation and repair. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;(346):26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]