Abstract

Legionella longbeachae is a very uncommon cause of community acquired pneumonia in Western countries. L. longbeachae does not grow on blood agar media and is usually not detected by sputum gram stain or blood culture. Furthermore Legionella urinary antigen testing fails to detect it. In this report we described a 79-year-old man with polymyalgia rheumatica under systemic corticosteroid treatment without other additional risk factors who developed a cultured-proven L. longbeachae community-acquired pneumonia complicated by an acute respiratory distress syndrome with septic shock. This case report demonstrates that non-pneumophila Legionella species must be taken into account as casual agents of community acquired pneumonia even in mild immunosuppressed patients, and empiric anti-Legionella antimicrobial coverage might be indicated until Legionella has definitively been rule out by adequate testing.

Keywords: Legionella longbeachae, community-acquired pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock.

Introduction

In most outpatients with suspected community acquired pneumonia microbial diagnosis is not mandatory since empiric antibiotic treatment is usually succesful. Clinical features and radiologic findings usually fail to identify the etiologic pathogen. Immunosuppressed patients deserve special attention and invasive procedures are compulsory in order to obtain sputum to make specific diagnosis. Empiric antimicrobial coverage should be tailored to treat the most likely pathogen in accordance to individual patient characteristics.

Case report

A 79-year-old man presented to the emergency department of the Regional Hospital of Bellinzona, Switzerland with a 2-day history of fever and unproductive cough as well as dyspnea on exertion. Previous history was remarkable for chronic corticosteroid use (10 mg daily of prednisone for eight months to treat polymyalgia rheumatica without giant cell arteritis). He was a non-smoker and did not have pre-existing pulmonary diseases. He had not travelled abroad recently, but was gardening during the last week before hospital admission.

On initial presentation, his temperature was 38.5° C, heart rate was 95 beats/min, blood pressure was 128/64 mmHg and his respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. Physical examination revealed fine crackles of the left lower lobe whereas other findings were normal. Initial oxygen saturation was 94% while breathing room air. Laboratory values were remarkable for anemia (9.1 g/dL, normal range 14-18 g/dL) elevated C-reactive protein (CRP 373 mg/L, normal <5 mg/L) and elevated creatinine (141 µmol/L, normal <106 µmol/L). White blood cell count was 10.1 × 109 cell/l with a differential showing 83% neutrophils and 8.5% lymphocytes. Pneumococcal and legionella urinary antigen tests were negative. Cultures of blood showed no growth. Chest radiographs did not show focal consolidations. He initiated antibiotic therapy with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g/24 h). Thereafter he developed a highly productive cough requiring a cough-assist (CoughAssist CM-3200, Megamed, Cham, Switzerland) to successfully clear the bronchial tree.

Two days later he developed a rapid progressive respiratory failure with an impending hemodynamic instability. A chest radiograph revealed an opacification of the left lung suggesting a nearly complete atelectasis; therefore, he underwent intubation. A bronchoscopy did not detect any endobronchial obstruction and on ultrasonography only a minimal left side pleural effusion was visible.

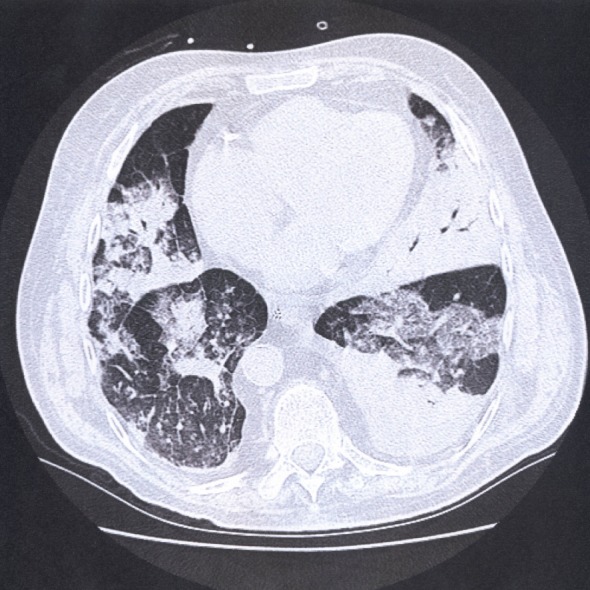

After obtaining secretions from the left upper and lower lobes with mini lavage for culture antibiotic treatment was changed to intravenous imipenem-cilastatin (500 mg/6 h) plus clarithromycin (500 mg/12 h). Prednisone dosage was increased up to 50 mg daily in order to prevent adrenal insufficiency and reduced to 20 mg/d four days later. He was then transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of the regional hospital of Mendrisio, Switzerland due to lack of free beds in Bellinzona. On admission the patient was ventilated on pressure-controlled mode with an fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 80%, a peak airway pressure <30 cm H2O, and a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) between 8-10 cm H2O in order to maintain oxygen saturation (SaO2) >92%. The paO2/FIO2 ratio was <200 mmHg. The hemodynamic was supported with norepinephrine (doses between 10-15 mcg/min). A chest computer tomography revealed an airspace consolidation of the left lower lobe and bilateral infiltrates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the chest one day after admission to the intensive care unit showing bilateral infiltrates and airspace consolidation of the left lower lobe.

A transthoracic echocardiography excluded a left ventricular dysfunction, and mitral and aortic valves appeared normal. A bronchoalveolar lavage sample showed a neutrophil predominance (>50%). Despite regression of the inflammatory parameters (CRP from 350 to 129 mg/L and procalcitonin from 6.3 to 2.2 µg/L in three days) high fever persisted with abundant tracheal secretion requiring frequent aspirations and therefore we replaced clarithromycin with intravenous levofloxacin (500 mg/12 h).

The bronchial sample obtained on the day of intubation was cultured on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar medium on which Legionella longbeachae surprisingly grew. Cultures for other bacteria (including mycobacteria) respiratory viruses and fungi remained negative.

These results allowed us to make a definitive diagnosis of L. longbeachae community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome with septic shock. The clinical course was characterized by a progressive improvement until the sixth day after admission to the ICU. Thereafter, we observed a new worsening of the respiratory parameters without an apparent cause requiring higher FIO2 and PEEP levels. In the absence of clinical signs of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) further bronchial samples were not obtained and antibiotic coverage remained unchanged. Despite higher FIO2 and PEEP levels the patient remained hypoxemic and, to protect the right ventricle from high intrathoracic pressure and to maintain an open-lung ventilation protective strategy (tidal volume of 6 ml per kg ideal body weight and peak airway pressure 2O), with a transient moderate permissive hypercapnia we decided to prone the patient with a consistent improvement allowing us to progressively reduce the respiratory support.

On day thirteen after admission to the ICU the patient developed again high fever with worsening respiratory parameters and hemodynamic instability consistent with a suspected impending VAP. After discussion with the family members and in accordance with the patient’s wishes, we decided not to perform the diagnostic evaluation of a suspected VAP and to withhold further support and the patient died shortly after. An autopsy was not performed.

Discussion

The patient described herein with polymyalgia rheumatica represents a sporadic CAP case with ARDS and septic shock due to L. longbeachae infection, diagnosed by culture from bronchial secretions. In accordance with the BAL cultures, and sample with a neutrophil predominance excluding an acute eosinophilic pneumonia and a cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, a contamination seems very unlikely [1]. The delay between the onset of the symptoms and appropriate antibiotic coverage is probably responsible for the development of the ARDS diagnosed in accordance with the Berlin definition [2]. By admission to our ICU the patient presented criteria for early prone positioning [3]. Under standard of care supine low tidal volume ventilation the patient progressively improved rendering prone ventilation initially no more indicated.

The only risk factor for Legionella pneumonia that we could identify was the long-term systemic steroids treatment (10 mg daily of prednisone) associated with depression of-cell mediated immunity. The four days transient increase of prednisone dosage in order to prevent adrenal insufficiency seems unlikely to be responsible for the poor patient’s outcome. To the best of our knowledge this case represents the first report of a L. longbeachae CAP complicated by ARDS with septic shock in a patient with corticosteroid-dependent polymyalgia rheumatica. Furthermore, this is the first description of a L. longbeachae infection in Switzerland.

L. longbeachae was first described as a cause of pneumonia in two Californian patients [4]. This infection is very uncommon in the United States and Europe [5] but it accounts for approximately 50% of all cases of Legionnaires’ disease in Australia and New Zealand [6], and it is far more prevalent than L. pneumophila in Southeast Asia [7].

L. longbeachae is one of the soil-dwelling pathogenetic Legionella species and its transmission has been linked to gardening and exposure to potting soil [8]. The present case was notified to the Regional Public Health authorities, but because it was a sporadic case of non-pneumophila Legionella infection, no additional epidemiological investigations were undertaken.

L. longbeachae is not only less prevalent than L. pneumophila but also probably less virulent [9]. This could be an explanation of its nearly exclusive occurrence in immunosuppressed hosts.

Pneumonia cases due to L. longbeachae reported from outside Australia occurred in immunocompromized patients: those undergone splenectomy, under immunosuppressive drugs for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or in transplant recipients [10]. Garcia and coll. reported a fatal case of community-acquired pneumonia due to L. longbeachae in Spain [11]. Their young patient with SLE was also under corticosteroid treatment, but in contrast to our patient she had one important additional risk factor for Legionella pneumonia: cigarettes smoking [12]. Moreover despite severe hypoxemia this patient did not fulfill all the criteria for ARDS diagnosis because hydrostatic pulmonary edema was formally not excluded (eg echocardiography).

The widespread introduction of Legionella urinary antigen testing into many hospital laboratories has resulted in a decreasing use of cultures and serology studies [13]. Although urinary antigen test remains positive even during administration of empiric anti-Legionella antibiotics, it is helpful in patients with unproductive cough and the test-result is usually available within hours permitting an early diagnosis, it is only specific for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 [14, 15]. Therefore it is likely that many infections caused by non-pneumophila species remain undiagnosed, as in our patient at hospital admission. Legionella spp. does not grow on blood agar media, and are usually not detected by sputum Gram stain or blood culture.

The standard media for Legionella isolation is buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar (BCYE) eventually supplemented with anisomycin, dyes, polymycin and vancomycin to reduce sample contamination. Our findings support the importance of examining sputum for Legionella spp. by cultural methods when pneumonia is suspected, especially in the immunocompromized host, where early recognition of the responsible pathogen and appropriate antibiotic therapy are crucial for the patient’s survival [16].

Furthermore, the sensitivity of Legionella urinary antigen test depends on clinical severity of pneumonia, so that a mild pneumonia or an early-onset pneumonia may go undiagnosed if the test is used alone [14, 15].

In summary, this culture-proven case of L. longbeachae infection demonstrates that non-pneumophila Legionella species must be considered as casual agents of pneumonia even in mild immunosuppressed patients. It should be noted that non-pneumophila Legionella infections are probably underreported because urinary antigen testing and serology fail to detect these pathogens and because sputum culture on appropriate media is not always standard practice in the CAP diagnosis.

A delay in diagnosis and in appropriate antibiotic treatment could significantly affect patients’ outcome, especially in the immunocompromized hosts.

Since sputum cultures take several days, empiric anti-Legionella antibiotic coverage and real-time PCR testing should be considered in high-risk patients. Finally, we suggest to administer anti-Legionella antibiotics in severe CAPs if the urinary antigen test is negative, unless another pathogen has been detected as the causal agent and the involvement of Legionella has, definitively, been ruled out.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Orlando Petrini PhD, ECPM, Director of the Cantonal Institute of Microbiology, Bellinzona, Switzerland, for providing editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support Nil.

Conflict of interest None declared.

Cite as: Reynaldos Canton Migotto T, Györik Lora S, Gaia V, Pagnamenta A. ARDS with septic shock due to Legionella longbeachae pneumonia in a patient with polymyalgia rheumatic. Heart, Lung and Vessels. 2014; 6(2): 114-118.

References

- Schwarz M I, Albert R K. "Imitators" of the ARDS: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Chest. 2004;125:1530–1535. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri V M, Rubenfeld G D, Thompson B T, Ferguson N D, Caldwell E. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard J C, Beuret P, Gacouin A, Boulain T. et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney R M, Porschen R K, Edelstein P H, Bissett M L, Harris P P, Bondell S P. et al. Legionella longbeachae species nova, another etiologic agent of human pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:739–743. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-6-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields B S, Benson R F, Besser R E. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:506–526. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannes K, Roche P W, Roberts A, Liu C, Firestone S M, Bartlett M. et al. Australia's notifiable diseases status, 2004, annual report of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Commun Dis Intell. 2006;30:1–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares C R, Wangroongsarb P, Chantra S, Paveenkitiporn W, Tondella M L, Benson R F. et al. Epidemiology of severe pneumonia caused by Legionella longbeachae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydia pneumoniae: 1-year, population-based surveillance for severe pneumonia in Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:147–155. doi: 10.1086/523003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legionnaires' disease associated with potting soil-California, Oregon and Washington, May-June 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:777–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry Ali O A, Zink S, von Lackum N K, Abu-Kwaik Y. Comparative assessment of virulence Traits in Legionella spp. Microbiology. 2003;149:631–641. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kümpers P, Tiede A, Kirschner P, Girke J, Ganser A, Peest D. Legionnaires' disease in immunocompromised patients: a case report of Legionella longbeachae pneumonia and review of the literature. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2008;57:384–387. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García C, Ugalde E, Campo A B, Miñambres E, Kovács N. Fatal case of community-acquired pneumonia caused by Legionella longbeachae in a patient with sistemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:116–118. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Boer J W, Nijhof J, Friesema I. Risk factors for sporadic community-acquired Legionnaires' disease. A 3-year national case-control study. Public Health. 2006;120:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benin A, Benson R F, Besser R E. Trends in legionnaires disease, 1980-1998: decliningmortality and new pattern of diagnosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1039–1046. doi: 10.1086/342903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Baum H, Ewig S, Marre R, Suttorp N, Gonschior S, Welte T. et al. Community-acquired Legionella pneumonia: new insights from the German competence network for community acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1356–1364. doi: 10.1086/586741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Noguchi Y, Jackson J L, Miyashita J, Hayashino Y, Kamiya T. et al. Systemic review and metaanalysis. Urinary antigen tests for Legionellosis. Chest. 2009;136:1576–1785. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell L A, Wunderink R G, Anzueto A, Bartlett J G, Campbell G D, Dean N C. et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired Pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [(Suppl. 2)] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]