Abstract

Objective

To determine whether risk factors associated with Grade (Gr) 2–4 intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) differs between African ancestry and white subjects.

Study design

Inborn, appropriate for gestational age (GA) infants with birth weights (BW) 500–1250 grams and exposed to >1 dose of antenatal steroids were enrolled in 24 neonatal intensive care units. Cases had Gr 2–4 IVH and controls matched for site, race and BW range had 2 normal ultrasounds read centrally. Multivariate logistic regression modeling identified factors associated with IVH across African ancestry and white race.

Results

Subjects included 579 African ancestry or white race infants with Gr 2–4 IVH and 532 controls. Mothers of African ancestry children were less educated, and white case mothers were more likely to have > 1 prenatal visit and have a multiple gestation (P ≤.01 for all). Increasing GA (P =.01), preeclampsia (P < .001), complete antenatal steroid exposure (P = .02), cesarean delivery (P < .001) and white race (P = .01) were associated with decreased risk for IVH. Chorioamnionitis (P = .01), Apgar< 3 at 5 min (P < .004), surfactant (P < .001) and high frequency ventilation (P < .001) were associated with increased risk for IVH. Among African ancestry infants, having >1 prenatal visit was associated with decreased risk (P = .02). Among white infants, multiple gestation was associated with increased risk (P < .001) and higher maternal education with decreased IVH risk (P < .05).

Conclusion

Risk for IVH differs between African ancestry and white infants and may be attributable to both race and health care disparities.

Keywords: preterm infant, intraventricular hemorrhage, race, multiple gestation, prenatal care

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) is a developmental disorder with significant neurodevelopmental morbidity.[1–7] Often attributed to alterations in cerebral blood flow to the immature germinal matrix microvasculature, IVH occurs against the backdrop of preterm birth in which risk and protective environmental factors have long been known.[8–12]

Women of African ancestry are at greater risk for preterm labor and delivery than white women,[13–16] and, even in the era of sophisticated perinatal intensive care strategies, a disproportionate number of very low birth weight infants are born to African ancestry mothers.[14, 15] Compared with white women, more African ancestry women who deliver prematurely have inadequate prenatal care and less education, and their neonates are less likely to receive surfactant or assisted ventilation.[17] There is a 2-fold higher rate of IVH-related mortality in African ancestry neonates,[18] suggesting that both preterm birth and its sequelae reflect the interaction of race and health care disparities.

Lower gestational age (GA) and birth weight (BW), male sex, white race, neonatal transport, chorioamnionitis, illness severity, delivery room resuscitation, assisted ventilation, and respiratory distress syndrome and its complications are associated with increased risk for IVH, and antenatal corticosteroids, cesarean delivery and preeclampsia are all correlated with a decreased risk for hemorrhage.[19–24] However, advances in neonatal and perinatal care and the increased survival of extremely low birth weight infants may have altered these associations.[ 25] The contribution of race and healthcare disparity to the incidence of IVH remains largely unexplored. The objective of this report is to evaluate whether risk factors associated with IVH differ in a recent, prospective cohort of appropriate for GA for African ancestry and white inborn infants exposed to partial or complete course of antenatal steroid exposure and whose cranial ultrasounds were centrally read [26, 27].

METHODS

Infants born June 1, 2007, and October 31, 2012, with BW 500–1250g with Grade (Gr) 2–4 IVH and matched infants with normal cranial ultrasound of the same BW range were enrolled into a prospective study of the environmental and genetic risk factors for IVH at 24 university-affiliated hospitals in the US and Sweden. The study procedures and protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent(s)/guardian(s) from cases and controls.

Case infants were eligible if they had Gr 2–4 IVH based upon masked review of cranial ultrasound by sonographers and met the following criteria: (1) inborn; (2) exposed to at least one dose of antenatal steroid exposure; (3) BW 500–1250 g; (4) appropriate size for GA;[28] (5) no evidence of congenital or chromosomal disorders or infections; (6) no family history of coagulopathy; and (7) not a sibling of an enrolled subject. Control infants met these criteria, had two normal cranial ultrasound within the required time intervals described below and were matched to cases based on the following criteria: (1) site; (2) sex; and (3) BW range (ie, 500–749 g; 750–999 g; 1000–1250 g). In addition, every effort was made to match controls based on self-reported maternal race and ethnicity. Enrollment was limited to one sibling of a multiple birth set; if more than one sibling of a multiple birth set had IVH, then the sibling to be included as a case was randomly selected. If both multiples had the same grade of IVH, the one enrolled was selected from a random table; if not similar, the one with the higher grade of IVH was enrolled.

Eligibility and study group were based upon clinical cranial ultrasound. Cases had Gr 2–4 IVH within the first 28 postnatal days (PND); controls had 2 normal cranial ultrasound, the first within day 5–10 and the second within PND 21–35, both without IVH, germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH), periventricular leukomalacia, ventriculomegaly or central nervous system malformations. The grading system for Gr 2–4 IVH follows Papile et al: [29] Gr 2, GMH with blood within the ventricular system; Gr 3, GMH with blood filling at least 50% of the ventricular system and ventricles measuring at least 1.1 cm at the mid-body of the lateral ventricle on a sagittal scan; Gr 4, GMH with intraventricular and intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Although initial screening was based on imaging reports from patient records, eligibility was confirmed by at least one site sonographer who had successfully completed standardized online study training showing images of GMH, grades 2 - 4 IVH and ventriculomegaly. All site sonographers were required to pass an online quiz composed of 10 different sets of ultrasound images prior to being “certified” to read the site ultrasounds for study enrollment.

Following subject enrollment, cranial ultrasound were submitted for central review by at least one of four study sonographers masked to the subjects’ case-control status. Eligibility and group assignment were based upon the following criteria: GMH, ventriculomegaly and Gr IVH. Images were sent to a second masked sonographer for review when the site and central readings were not in agreement. When both central reviewers concurred that images did not support eligibility, the subject was excluded. If the two disagreed, images were sent to the study’s head sonographer for final review.

Data were collected from medical records and entered into a secure online database housed at Yale University. Maternal data included age, highest level of education, prenatal care, primary medical insurance, maternal magnesium sulfate < 72 hours prior to delivery, preeclampsia, clinical chorioamnionitis and antenatal steroid exposure < 7 days prior to birth.

Delivery room variables included Apgar scores and need for resuscitation. Neonatal data included early receipt of indomethacin within first 6–12 hours following birth, caffeine within first 2 PND, high frequency ventilation (HFV) within the first 7 PND, GA, BW, sex, multiple birth, and reported race and ethnicity. In addition, data for surfactant, pneumothorax and seizures were collected for the first 28 PND. Data definitions are provided in Table I (available at www.jpeds.com).

Table I.

Data Definitions

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Clinical chorioamnionitis | Two or more of the following criteria in the absence of other diseases: fetal tachycardia, maternal tachycardia, uterine tenderness or maternal fever of >100.4 degrees F. Histologic evidence of chorioamnionitis without the presence of other symptoms was not coded as chorioamnionitis |

| Complete course of antenatal steroids | Complete course of betamethasone: 2 doses given 12–24 hours apart; complete course of dexamethasone: 4 doses given 6–12 hours apart. |

| High frequency ventilation | High frequency oscillatory or jet ventilation in the first 7 postnatal days. |

| Intubation for resuscitation in delivery room | Infant was intubated in the delivery room for resuscitation, or if intubated for surfactant administration, remained intubated until stabilized in the NICU. |

| Multiple gestation | Gestation resulting in > 1 live birth, in which more than one embryo was successfully implanted, including those in which fetal demise or reduction occurred. |

| Preeclampsia | Sustained elevation in blood pressure of >140 systolic and/or >90 diastolic, accompanied by proteinuria, after 20 weeks gestation in a previously normotensive woman. |

| Prenatal care | At least one visit during the pregnancy leading to the subject’s birth. |

| Prophylactic indomethacin | Indomethacin administered for the prevention of IVH within 6–12 postnatal hours. |

The neonates in this report are part of an ongoing study investigating the genetic and environmental contributions to IVH, and 1100 of the 1111 (99%) infants had a genetic assessment of race.[30, 31]

Statistical Analyses

The primary outcome was Gr 2–4 IVH. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student t-test or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test and categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher exact test, comparing African ancestry cases vs. African ancestry controls, white cases vs. white controls, all cases vs. all controls, and African ancestry cases vs. white cases. Stratified categorical data were analyzed using the Mantel Haenzel test. To identify risk factors independently and significantly associated with Gr 2–4 IVH a multivariate logistic regression model was built based on the stepwise variable selection using site, significant variables in the univariate analyses (all cases vs. all controls) and their interactions with race. Post-hoc univariate analyses were performed with selected data for African ancestry vs. white cases and for those variables with significant raceinteraction terms in the logistic regression model. For all analyses, SAS (version 9.3) was used and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

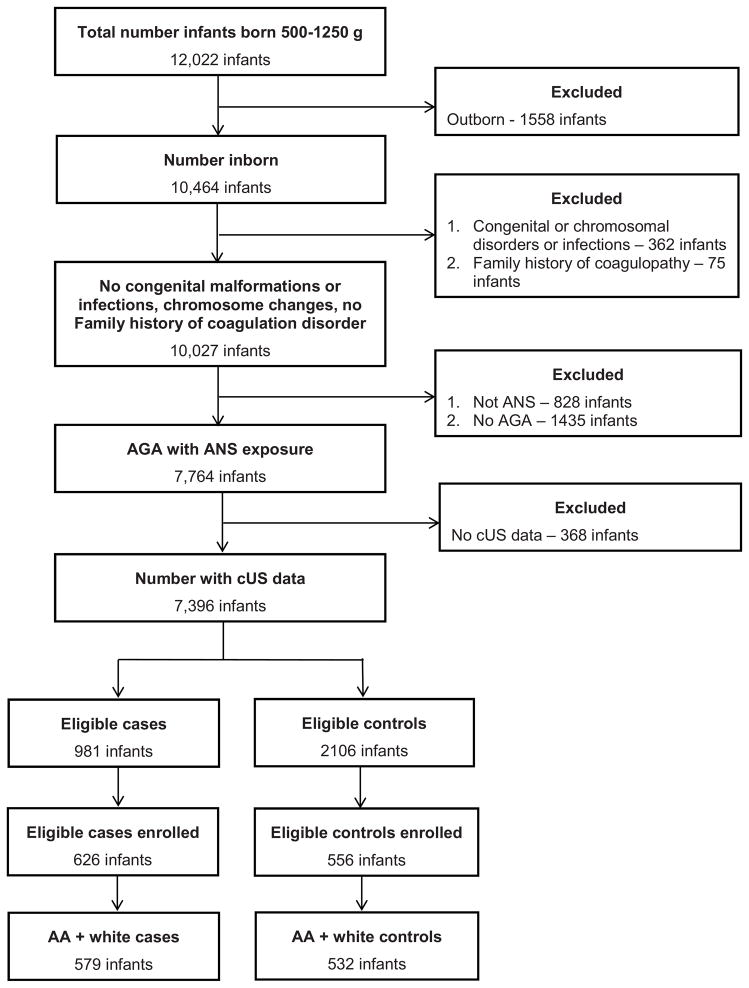

During the study period, 12, 022 infants were screened for study eligibility at the participating sites (Figure; available at www.jepds.com). There were 981 infants with Gr 2–4 IVH who met eligibility criteria as cases; of these 146 infants died in the NICU. Infants who died prior to enrollment had lower birth weight than infants enrolled in the study (data not shown). Consent was obtained for 626 case infants; 579 were African ancestry or white race and were enrolled. Case infants excluded were: 18 Asian, 15 > one race, 2 American Indian/Alaska Native, 2 Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, and 10 unknown. 532 control infants were enrolled; these 1,111 infants (579 cases and 532 controls) form the basis of this report.

Figure 1.

Details of the study population

Significantly lower BWs and GA were noted among all cases compared with all control infants and within the African ancestry cases vs. control and white cases vs. control groups (Table II). Although cases were more likely to have been products of multiple gestation pregnancies, this association was significantly more common among white rather than African ancestry infants.

Table II.

Demographics of Study Subjects

| African Ancestry | White | African Ancestry and White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | |

| Number of subjects | 242 | 210 | 337 | 322 | 579 | 532 | |||

| Birth weight (N,SD) | 776 (242, 185) | 818 (210, 183) | 0.016 | 814 (337, 184) | 851 (322, 173) | 0.009 | 798 (185) | 838 (178) | 0.003 |

| GA wks (N,SD) | 25.5 (242, 1.7) | 26.3 (210, 1.8) | <.001 | 25.6 (337, 1.6) | 26.6 (322, 1.6) | <.001 | 25.6 (1.6) | 26.4 (1.7) | <.001 |

| Male subjects (%) | 141/242 (58.3) | 113/210 (53.8) | 0.34 | 196/337 (58.2) | 176/322 (54.7) | 0.39 | 337/579 (58.2) | 289/532 (54.3) | 0.20 |

| Hispanic (%) | 3/242 (1.2) | 4/210 (1.9) | 0.71 | 54/337 (16.0) | 48/322 (14.9) | 0.75 | 57/579 (9.8) | 52/532 (9.8) | 1 |

| Grade 2 (%) | 90 (37.2) | 109 (32.3) | 199 (34.4) | ||||||

| Grade 3 (%) | 53 (21.9) | 96 (28.5) | 149 (25.7) | ||||||

| Grade 4 (%) | 99 (40.9) | 132 (39.2) | 231 (39.9) | ||||||

| Multiple gestation (%) | 37/242 (15.3) | 30/210 (14.3) | 0.79 | 113/337 (33.5) | 68/322 (21.1) | <.001 | 150/579 (25.9) | 98/532 (18.4) | 0.003 |

Abbreviation: (SD), Standard Deviation; N/A, not applicable

Among the maternal characteristics (Table III), case mothers had a higher rate of clinical chorioamnionitis, but a lower frequency of preeclampsia, compared with all control mothers, and within the African ancestry cases vs. control and white cases vs. control groups. In the whole cohort and among African ancestry infants, case mothers were also less likely to have at least one prenatal visit or to have received magnesium sulfate or a complete course of antenatal steroid exposure than mothers of controls (Table IV). White case infants were also less likely to have received antenatal steroid exposure than controls. African ancestry case mothers had lower levels of education; 23.0% reporting < high school education compared with 16.0% white case mothers (P < .001 for highest level of education). Medicaid was the primary insurance for 67.4% of African ancestry case mothers compared with 39.2% of white case mothers (P < .001 across all insurance). At least one prenatal visit was documented among 92.1% African ancestry case mothers compared with 97.3% mothers of white cases (P = .006). Similarly, African ancestry mothers were less likely to have received a complete course of antenatal steroid exposure (41.3 vs.50.7%, P = .03).

Table III.

Maternal Characteristics

| African Ancestry | White | African Ancestry and White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | |

| Maternal Age (N, SD) | 25.8(240, 6.3) | 26.8(204,6.3) | 0.11 | 27.7 (316, 6.5) | 28.1 (300,6.6) | 0.45 | 26.9 (556, 6.5) | 27.6 (504, 6.5) | 0.09 |

| Highest Level of Maternal Education | |||||||||

| Less than High School (%) | 55/239 (23.0) | 34/205 (16.6) | 0.33 | 53/332 (16.0) | 50/317 (15.8) | 0.29 | 108/571 (18.9) | 84/522 (16.1) | 0.33 |

| HS Grad or GED (%) | 87/239 (36.4) | 85/205 (41.5) | 101/332 (30.4) | 76/317 (24.0) | 188/571 (32.9) | 161/522 (30.8) | |||

| Some college (%) | 76/239 (31.8) | 64/205 (31.2) | 86/332 (25.9) | 91/317 (28.7) | 162/571 (28.4) | 155/522 (29.7) | |||

| ≥ 4 year college degree (%) | 21/239 (8.8) | 22/205 (10.7) | 92/332 (27.7) | 100/317 (31.5) | 113/571 (19.8) | 122/522 (23.4) | |||

| Gravidaa (N, range) | 2 (242, 1–11) | 3 (210, 1–15) | 0.15 | 2 (337, 1–14) | 2 (322, 1–15) | 0.16 | 2 (579, 1–14) | 2 (532, 1–15) | 0.78 |

| Paritya (N, range) | 2 (242, 1–9) | 2 (210, 1–9) | 0.15 | 2 (337, 1–8) | 1 (322, 1–7) | 0.04 | 2 (579, 1–9) | 2 (532, 1–9) | 0.55 |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis (%) | 95/242 (39.3) | 50/210 (23.8) | <.001 | 109/337 (32.3) | 65/322 (20.2) | <.001 | 204/579 (35.2) | 115/532 (21.6) | <.001 |

| Preeclampsia (%) | 23/242 (9.5) | 71/210 (33.8) | <.001 | 34/336 (10.1) | 85/321 (26.5) | <.001 | 57/578 (9.9) | 156/531 (29.4) | <.001 |

Median value

Table IV.

Prenatal Care

| African Ancestry | White | African Ancestry and White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | |

| At least 1 prenatal visit (%) | 223/242 (92.1) | 204/210 (97.1) | 0.02 | 326/335 (97.3) | 316/321 (98.4) | 0.42 | 549/577 (95.1) | 520/531 (97.9) | 0.01 |

| Primary Medical Insurance | |||||||||

| Medicaid (%) | 163/242 (67.4) | 138/210 (65.7) | 0.83 | 132/337 (39.2) | 115/322 (35.7) | 0.08 | 295/579 (50.9) | 253/532 (47.6) | 0.27 |

| Private (%) | 61/242 (25.2) | 51/210 (24.3) | 118/337 (35.0) | 140/322 (43.5) | 179/579 (30.9) | 191/532 (35.9) | |||

| Self-Pay (%) | 3/242 (1.2) | 5/210 (2.4) | 13/337 (3.9) | 5/322 (1.6) | 16/579 (2.8) | 10/532 (1.9) | |||

| Uninsured (%) | 8/242 (3.3) | 10/210 (4.8) | 5/337 (1.5) | 7/322 (2.2) | 13/579 (2.2) | 17/532 (3.2) | |||

| Unknown or Other (%) | 7/242 (2.9) | 6/210 (2.9) | 69/337 (20.5) | 55/322 (17.1) | 76/579 (13.1) | 61/532 (11.5) | |||

| Magnesium sulfatea (%) | 122/242 (50.4) | 136/210 (64.8) | 0.002 | 168/337 (49.9) | 184/322 (57.1) | 0.06 | 290/579 (50.1) | 320/532 (60.2) | <.001 |

| Antenatal steroid exposure within 7 days prior to delivery | |||||||||

| Any ANS (%) | 196/242 (81.0) | 169/210 (80.5) | 0.90 | 279/337 (82.8) | 255/322 (79.2) | 0.27 | 475/579 (82.0) | 424/532 (79.7) | 0.36 |

| Complete Course ANS(%) | 100/242 (41.3) | 123/210 (58.6) | <.001 | 171/337 (50.7) | 196/322 (60.9) | 0.01 | 271/579 (46.8) | 319/532 (60.0) | <.001 |

Administered within 72 hours prior to delivery

Neonatal characteristics are shown in Table V. Cases (overall and among African ancestry and white infants) were less likely than controls to have been delivered by cesarean delivery, had a higher rate of Apgar scores < 3 at both 1 and 5 min and were more likely to require intubation for resuscitation, chest compressions and epinephrine in the delivery room. Cases were less likely to have received CPAP for resuscitation but more likely to have been treated with HFV during the first postnatal week and to have received surfactant. Cases more often experienced both pneumothoraces and seizures when compared with controls.

Table V.

Neonatal Characteristics

| African Ancestry | White | African Ancestry and White | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | IVH Gr 2–4 Cases | Controls | P Value | |

| Delivery Room Variables | |||||||||

| Apgar score < 3 | |||||||||

| At 1 minute (%) | 117/242 (48.3) | 70/210 (33.3) | 0.002 | 119/337 (35.3) | 80/322 (24.8) | 0.004 | 236/579 (40.8) | 150/532 (28.2) | <.001 |

| At 5 minutes (%) | 30/242 (12.4) | 9/210 (4.3) | 0.002 | 40/337 (11.9) | 15/322 (4.7) | 0.001 | 70/579 (12.1) | 24/532 (4.5) | <.001 |

| Delivery by cesarean (%) | 129/242 (53.3) | 145/210 (69.0) | <.001 | 193/337 (57.3) | 238/322 (73.9) | <.001 | 322/579 (55.6) | 383/532 (72.0) | <.001 |

| Bag and mask ventilation (%) | 210/241 (87.1) | 169/210 (80.5) | 0.07 | 297/337 (88.1) | 274/322 (85.1) | 0.25 | 507/578 (87.7) | 443/532 (83.3) | 0.04 |

| CPAP (%) | 57/242 (23.6) | 70/210 (33.3) | 0.03 | 79/337 (23.4) | 120/322 (37.3) | <.001 | 136/579 (23.5) | 190/532 (35.7) | <.001 |

| Intubation for resuscitation (%) | 208/242 (86.0) | 139/210 (66.2) | <.001 | 277/337 (82.2) | 207/322 (64.3) | <.001 | 485/579 (83.8) | 346/532 (65.0) | <.001 |

| Chest compressions (%) | 29/242 (12.0) | 14/210 (6.7) | 0.08 | 36/337 (10.7) | 19/322 (5.9) | 0.03 | 65/579 (11.2) | 33/532 (6.2) | 0.004 |

| Epinephrine (%) | 25/242 (10.3) | 7/210 (3.3) | 0.005 | 16/337 (4.7) | 10/322 (3.1) | 0.32 | 41/579 (7.1) | 17/532 (3.2) | 0.004 |

| Neonatal Interventions | |||||||||

| Prophylactic indomethacina (%) | 51/242 (21.1) | 61/210 (29.0) | 0.063 | 94/337 (27.9) | 83/322 (25.8) | 0.60 | 145/579 (25.0) | 144/532 (27.1) | 0.45 |

| High frequency ventilationb (%) | 225/242 (93.0) | 164/210 (78.1) | <.001 | 324/337 (96.1) | 266/322 (82.6) | <.001 | 549/579 (94.8) | 430/532 (80.8) | <.001 |

| Surfactantc (%) | 107/242 (44.2) | 42/209 (20.1) | <.001 | 189/337 (56.1) | 73/322 (22.7) | <.001 | 296/579 (51.1) | 115/531 (21.7) | <.001 |

| Neonatal degree of illness and morbidities | |||||||||

| Pneumothoraxc (%) | 18/242 (7.4) | 5/210 (2.4) | 0.02 | 39/337 (11.6) | 12/322 (3.7) | <.001 | 57/579 (9.8) | 17/532 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Multiple seizuresc (%) | 8/239 (3.3) | 0/210 (0) | 0.008 | 8/325 (2.5) | 3/319 (0.9) | 0.22 | 16/564 (2.8) | 3/528 (0.6) | 0.004 |

6–12 postnatal hours;

1–7 postnatal days;

1-28 postnatal days

Comparison of African ancestry and white cases revealed that African ancestry infants were more likely to have one min (P = .002) but not five min Apgar scores <3. African ancestry cases were also more likely than white cases to receive epinephrine (P = .01) but less likely to receive surfactant (P = .005).

Demographics, Health Care, and the Risk for IVH

The model shown in Table VI (OR, 95%CI) demonstrates that increasing GA, preeclampsia, a complete course of antenatal steroid exposure, cesarean delivery and white race were associated with decreased risk for IVH. In contrast, chorioamnionitis, Apgar< 3 at 5 min, surfactant and HFV increased risk for IVH. Multiple gestation increased risk for IVH only for white infants. Having at least 1 prenatal visit decreased risk for African ancestry neonates and maternal college education was associated with a lower risk for IVH for white infants.

Table VI.

Logistic regression model for risk for IVH with all African ancestry and white subjects

| Effect | p-value | OR | 95% Confidence Limits | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA weeks | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.97 |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis | 0.01 | 1.48 | 1.08 | 2.02 |

| Preeclampsia | 0.001 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.76 |

| Complete course antenatal steroids | 0.02 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.94 |

| Apgar score < 3 at 5 | 0.004 | 2.13 | 1.27 | 3.59 |

| Cesarean delivery | <.0001 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.67 |

| Surfactant | <.0001 | 3.32 | 2.06 | 5.34 |

| High frequency ventilation | <.0001 | 2.61 | 1.94 | 3.51 |

| White race | 0.012 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.75 |

| College degree x white | 0.047 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.99 |

| Prenatal visit x African ancestry | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.82 |

| Multiple gestation x White | <.0001 | 2.28 | 1.51 | 3.45 |

Exploratory Post Hoc Analyses

To further explore the variable-by-racial interaction terms that were independent and important predictors of Gr 2–4 IVH in the model, exploratory post hoc analyses were performed. Overall white mothers were more likely to have had in vitro fertilization (IVF) for pregnancy induction compared with African ancestry mothers [31/659 (4.7%) compared with 4/452 (0.9%), P < .001). In addition, white mothers with multiple gestation pregnancies tended to have more IVF induced pregnancies [white vs. African ancestry: 22/181 (12.2%) vs. 2/67 (3.0%), P = .03). Because of a potential white-IVF bias, the race-by-multiple gestation analysis was repeated while excluding IVF assisted pregnancies and the results were unchanged (P<.001).

DISCUSSION

After controlling for confounding variables in this well-characterized case-control study, relative to white preterm infants, African ancestry neonates were observed to be at significantly increased risk of Gr 2–4 IVH. This is the first study to report that for developing Gr 2–4 IVH, the previously demonstrated protective effect of being African ancestry as a preterm infant [32] is no longer evident. African ancestry mothers had more evidence of risk, including inadequate prenatal care and lower maternal educational and insurance status; similarly, their infants had less antenatal steroid exposure and, most likely secondarily, a greater need for resuscitation. The potential causes of our reported new observation are likely multifactorial and may relate both to access to care and to uneven distribution of medical resources. Absence of prenatal care has previously been shown to increase risk of IVH, but the influence of race on this finding has not been previously explored.[33, 34] In our study, if the mothers had at least one prenatal visit, the risk for IVH among African ancestry infants significantly declined, suggesting that initiating maternal/fetal care prior to labor and delivery provides a distinct protective advantage.

We also report for the first time that multiple gestation pregnancies were associated with a higher risk of Gr 2–4 IVH for white neonates only. The published associations of plurality and 12 IVH report mixed results, but none include race in their analyses.[35–38] In our study, mothers of white IVH cases were more likely to be older, undergo IVF and experience cesarean delivery compared with African ancestry case mothers; these factors alone may not explain this association. Previous studies have not confirmed an association between IVF, multiple gestation and IVH; race was not included in these analyses.[23, 35, 39, 40] Our observation will need to be explored in additional cohorts.

We did examine the birth weight, gestational age and educational status of the cohort enrolled in Sweden compared with that in this country; the average birth weight and gestational age was lower and the educational status higher in the Swedish cohort (data not shown). The model for risk of IVH was analyzed with and without the inclusion of subjects from Sweden, the model for risk remained unchanged.

In our study, white infants whose mother had at least a college education had a decreased risk for IVH compared with African ancestry infants of mothers with college educations. It has been demonstrated that compared with white women, a higher percentage of African ancestry women who deliver prematurely have less post-high school education,[14–16, 41] but the association of education and IVH has been previously unexplored.

Finally, our study includes neonates from both the United States and Sweden, countries with different health care systems. The Swedish neonates had lower birth weights and gestational ages and higher levels of maternal education than infants born in the US. Notably, the model for IVH was unchanged when these subjects were excluded, confirming the validity of our findings.

The strengths of this study include the large and well-characterized cohort of appropriate for GA inborn neonates with at least exposure to a partial course of antenatal steroid exposure, centrally read cranial ultrasound and genotypes characterizing race. IVH is lower in infants exposed to a partial course compared with no antenatal steroid exposure, and lower with exposure to complete compared with partial antenatal steroid exposure (32); hence our cohort serves to interrogate emerging demographic and environmental risk for IVH.

A study limitation is lack of data regarding the number and timing of prenatal health visits. In addition, we do not have either the time of onset for IVH nor measures of thrombophilia, as atypical timing of IVH may be characterized by evidence of coagulopathy.[42] We did not collect physiologic measures of the cerebral circulation.[43, 44] Injury to the white matter of the brain is an important cause of neurodevelopmental impairment; we did not evaluate magnetic resonance imaging studies to detect white matter injury. Finally, the incidence of multiple gestation pregnancies in white mothers was almost double that in African ancestry mothers in our study and that finding may have influenced the analysis. However, preterm multiple births have been reported to be more frequent in the white population than in African ancestry women [45, 46] and may be attributable to differences in the use of assisted reproduction technology.[47–49] The analysis of our data omitting all neonates from IVF-induced pregnancies confirmed our primary findings.

Preterm birth represents one of the major pediatric public health problems of our time, and IVH is a significant morbidity of the prematurely born. Although we show that risk for Gr 2–4 IVH is greater among African ancestry compared with white infants, this finding is reduced by maternal attendance at a single prenatal visit. In addition, multiple gestation pregnancies were associated with a higher risk of Gr 2–4 for white infants only, suggesting underlying epigenetic or additional genetic factors. The high social and medical risk status of the mothers in this study reflects both racial and healthcare disparities between our groups and stresses the critical public health implications for the prevention of IVH in the prematurely-born.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our medical, nursing and research colleagues and the infants and their parents.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NS053865) and the National Institutes of Neurological Diseases and Stroke

ABBREVIATIONS

- BW

Birth weight

- GA

Gestational age

- GMH

Germinal matrix hemorrhage

- Gr

Grade

- HFV

High frequency ventilation

- IVH

Intraventricular hemorrhage

- IVF

In-vitro fertilization

- PND

Postnatal day

Appendix

Members of the Gene Targets for IVH Study include:

Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital and Ben Taub General Hospital: Cindy Bryant, BSN, CCRN, CCRP, Christopher Cassady, MD, Carmen Garcia, RN, BSN, Yvette R. Johnson, MD, MPH, Heidi E. Karpen, MD, Diane Kent, RN, Martha M. Munden, MD, Geneva Shores, RNC-LRN; Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital: John Cassese, MD, Angelita M. Hensman, RN, BSN, Elisa Vieira, BS, RN, Betty Vohr, MD, Michael Wallach, MD; East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine: James J. Cummings, MD, Scott S. MacGilvray, MD, Sherry Moseley, RN, Vickie Trapanotto, MD; Foundation for Blood Research: Walter Allan, MD; Indiana University School of Medicine and Riley Hospital for Children: Leslie R. Delaney, MD, Faithe Hamer, Brenda Poindexter, MD, Leslie Dawn Wilson, BS, CCRC, Shirley Wright-Coltart, RN, CCRP; Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital: Ulrika Ådén, MD, PhD, Marco Bartocci, MD, PhD, Hugo Lagercrantz, MD, Gordana Printz, RN, BSc; Loma Linda University School of Medicine: Lila Dalton, RN, CCRP, Andrew Hopper, MD, Leon Smith, LVN, CCRP, Kimberly Victor, PhD, RN, Betty Voltz, LVN, CRC, Beverly P. Wood, MD, Lionel Young; Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Queen Silvia Children’s Hospital: Jessica Alfsson, RN, Karin Sävman, MD, PhD; University of Alabama at Birmingham, Women’s and Infants’ Center: Waldemar Carlo, MD, Monica Collins, RN, MAED, Stuart A. Royal, MS, MD, Daniel W. Young, MD, Shirley Cosby, RN, BSN, Crystal Helms, RN, BSN; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences: Teresita Angtuaco, MD, Jeffrey R Kaiser, MD MA, N. Carol Sikes, BSN, MScN, Melanie J. Mason, RN, R.Whit Hall, MD; University of Kentucky: Henrietta Bada, MD, MPH, Harigovinda R. Challa, MD, Deborah L. Grider, RN, Vesna Kriss, MD, Tracey Robinson, RN, Vicki Whitehead, RN, CCRC; University of Miami–Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine, Holtz Children’s Hospital: George Abdenour, MD, Charles Bauer, MD, Gary Danton, MD, Daniel Montesinos, BA, Saigal Gaurav, MD, Willy Philias, MD, Uygar Teomete, MD; University of Michigan: John Barks, MD, PhD, Mary Christensen, BA, RRT, Ramon Sanchez, MD, Makayla Sieg, BSHA, Stephanie Wiggins, BS; University of New Mexico Health Science Center: Janell Fuller, MD, Lucille Papile, MD, Carol Hartenberger, RN, MPH, Connie Backstrom Lacy, RN, CCRC, Rebecca Montman, BSN, RNC, Julie Rohr, MSN, RNC, Jessica B. Williams, MD, Susan Williamson, MD; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital: Carl Bose, MD, Cynthia L. Clark, RN, Matthew Laughon, MD, MPH; University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Hospital: Soraya Abbasi, MD, Noah M. Cook MD, MTR, Toni Mancini RN, CCRC, BSN; University of Pennsylvania, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania: African ancestrysma Chaudhary BS, RRT, Christopher DeMauro, MD, Barbara Schmidt, MD, MSc; University of South Alabama, Children’s and Women’s Hospital: Ellen Dean, RNC, BS, Fabien Eyal, MD, Paul Maertens; University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, the Regional Medical Center Hospital: Thomas F. Boulden, MD, Harris L. Cohen, MD, Shelia Dempsey, RN, CCRC, Pam LeNoue, RN, Massroor Pourcyrous, MD; University of Utah and Intermountain Healthcare: Karie Bird, RN, BSN, Jill J. Burnett, BSN, Laura Cole, RN, Roger G. Faix, MD, Gary Hedlund, OD, Kevin Moore, MD, Manndi Loertscher, Karen Osborne, RN, BSN, CCRC, Carrie Rau, RN; Cindy Spencer, BSN, Kimberlee Weaver-Lewis MS, RN, Bradley A. Yoder, MD; University of Washington: Amanda T. Jones, BA, Dennis E. Mayock, MD, Manjiri Dighe, MD; Wake Forest School of Medicine, Forsyth Medical Center, Brenner Children’s Hospital: Patricia L. Brown, RN, T. Michael O’Shea, MD, Nancy Peters, RN; Washington University in St. Louis, the St. Louis Children’s Hospital: Terrie Inder, MBChB, MD, Karen Lukas, RN, Amit Mathur, MD, Robert McKinstry, MD, Joshua Shimony, MD, Jennifer Walker; Wayne State University, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Hutzel Women’s Hospital: Aparna Joshi, MD, Jay Ann Nelson, BSN, Seetha Shankaran, MD, Eunice H. Woldt, MSN; Yale University School of Medicine: Kenneth Baker, MD, Matthew J. Bizzarro, MD, Charles Duncan, MD, Richard Ehrenkranz, MD, Anita Farhi, RN, T.R. Goodman, MBChB, MD, Murat Gunel, MD, Jeffrey R. Gruen, MD, Karol Katz, MS, Monica Konstantino RN, BSN, Zhifa Liu, MS, Erin Loring, MS, CGC, Robert W. Makuch, PhD, Carol Nelson-Williams, PhD, JoAnn Poulsen, RN, Karen Schneider, MPH, Jan Taft, RN. Additional collaborators include:

ELGAN Study: Elizabeth Newton Allred, MS (Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health; Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Boston), Alan Leviton, MD, (Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Harvard); Oulu University: Mikko Hallman, MD, PhD (Department of Pediatrics, University of Oulu), Johanna Huusko, MSc (Department of Pediatrics); University of Iowa: Susan K. Berends, MA (Department of Pediatrics), Allison M. Momany, BS (Department of Pediatrics), Jeffrey C. Murray, MD, (Department of Pediatrics, University of Iowa College of Medicine; Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa College of Liberal Arts; Department of Preventive Medicine and Department of Epidemiology, University of Iowa), Nancy J. Weathers (College of Nursing).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurology. 2009;8:110–24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaino G, Khoshnood B, Kaminski M, Pierrat V, Marret S, Matis J, et al. Predictors of cerebral palsy in very preterm infants: the EPIPAGE prospective population-based cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:e119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maitre NL, Marshall DD, Price WA, Slaughter JC, O'Shea TM, Maxfield C, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infants with unilateral or bilateral periventricular hemorrhagic infarction. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1153–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roze E, Van Braeckel KNJA, van der Veere CN, Maathuis CGB, Martijn A, Bos AF. Functional outcome at school age of preterm infants with periventricular hemorrhagic infarction. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1493–500. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitaker AH, Feldman JF, Lorenz JM, McNicholas F, Fisher PW, Shen S, et al. Neonatal head ultrasound abnormalities in preterm infants and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:742–52. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luu TM, Ment L, Allan W, Schneider K, Vohr BR. Executive and Memory Function in Adolescents Born Very Preterm. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e639–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klebermass-Schrehof K, Czaba C, Olischar M, Fuiko R, Waldhoer T, Rona Z, et al. Impact of lowgrade intraventricular hemorrhage on long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2012;28:2085–92. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1897-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballabh P. Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants: mechanism of disease. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:1–8. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c1b176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed MA, Aly H. Transport of premature infants is associated with increased risk for intraventricular haemorrhage. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95:F403–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.183236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohamed MA, Aly H. Male gender is associated with intraventricular hemorrhage. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e333–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Atkins DL, Chameides L, Goldsmith JP, et al. Part 11: Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122:S516–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shalak L, Perlman JM. Hemorrhagic-ischemic cerebral injury in the preterm infant. Current concepts. Clin Perinatol. 2002;29:745–63. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(02)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schieve L, Handler A. Preterm delivery and perinatal death among black and white infants in a Chicago-area perinatal registry. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:356–63. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunlop AL, Salihu HM, Freymann GR, Smith CK, Brann AW. Very low birth weight births in Georgia, 1994–2005: trends and racial disparities. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:890–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0590-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrova A, Mehta R, Anwar M, Hiatt M, Hegyi T. Impact of race and ethnicity on the outcome of preterm infants below 32 weeks gestation. J Perinatol. 2003;23:404–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tierney-Gumaer R, Reifsnider E. Risk factors for low birth weight infants of Hispanic, African American, and White women in Bexar County, Texas. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25:390–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell EA, Holzman I, Kleinman LC, Wang J, Chassin MR. Surfactant use for premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome in three New York city hospitals: discordance of practice from a community clinician consensus standard. J Perinatol. 2010;30:590–5. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qureshi AI, Adil MM, Shafizadeh N, Majidi S. A 2-fold higher rate of intraventricular hemorrhage-related mortality in African American neonates and infants. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12:49–53. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.PEDS12568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCrea HJ, Ment LR. The diagnosis, management, and postnatal prevention of intraventricular hemorrhage in the preterm neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:777–92. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volpe JJ. The encephalopathy of prematurity--brain injury and impaired brain development inextricably intertwined. Seminars in pediatric neurology. 2009;16:167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent AL, Wright IM, Abdel-Latif ME. Mortality and adverse neurologic outcomes are greater in preterm male infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129:124–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborne DA, Evans N, Kluckow M. Hemodynamic and antecedent risk factors of early and late periventricular/intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2003;2003:33–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linder N, Haskin O, Levit O, Klinger G, Prince T, Naor N, et al. Risk factors for intraventricular hemorrhage in very low birth weight premature infants: A retrospective case-control study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e590–e5. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.e590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagliardi L, Rusconi F, Da Fre M, Mello G, Carnielli V, Di Lallo D, et al. Pregnancy disorders leading to very preterm birth influence neonatal outcomes: results of the population-based ACTION cohort study. Pediatric research. 2013;73:794–801. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126:443–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehler K, Grimme J, Abele J, Huenseler C, Roth B, Kribs A. Outcome of extremely low gestational age newborns after introduction of a revised protocol to assist preterm infants in their transition to extrauterine life. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:1232–9. doi: 10.1111/apa.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer SC, Msall ME. Optimizing neurodevelopmental outcomes after prematurity: lessons in neuroprotection and early intervention. Minerva Pediatr. 2010;62:485–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–8. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papile LS, Burstein J, Burstein Rea. Incidence and evolution of the subependymal intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with weights less than 1500 grams. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aden U, Lin A, Carlo W, Leviton A, Murray JC, Hallman M, et al. Candidate Gene Analysis: Severe Intraventricular Hemorrhage in Inborn Preterm Neonates. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1503–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilguvar K, Yasuno K, Niemela M, Ruigrok YM, von Und Zu Fraunberg M, van Duijn CM, et al. Susceptibility loci for intracranial aneurysm in European and Japanese populations. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1472–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shankaran S, Bauer CR, Bain R, Wright LL, Zachary J. Prenatal and perinatal risk and protective factors for neonatal intracranial hemorrhage. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:491–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170300045009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vural M, Yilmaz I, Ilikkan B, Erginoz E, Perk Y. Intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm newborns: risk factors and results from a University Hospital in Istanbul, 8 years after. Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2007;49:341–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorp JA, Jones PG, Clark RH, Knox E, Peabody JL. Perinatal factors associated with severe intracranial hemorrhage. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;185:859–62. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunner B, Hoeck M, Schermer E, Streif W, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U. Patent ductus arteriosus, low platelets, cyclooxygenase inhibitors, and intraventricular hemorrhage in very low birth weight preterm infants. The Journal of pediatrics. 2013;163:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leijser LM, Steggerda SJ, de Bruine FT, van der Grond J, Walther FJ, van Wezel-Meijler G. Brain imaging findings in very preterm infants throughout the neonatal period: part II. Relation with perinatal clinical data. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:111–5. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viscardi RM, Donn SM, Rayburn WF, Schork MA. Intraventricular h emorrhage in preterm twin gestation infants. J Perinatology. 1988;8:114–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayes EJ, Paul D, Ness A, Mackley A, Berghella V. Very-low-birthweight neonates: do outcomes differ in multiple compared with singleton gestations? American journal of perinatology. 2007;24:373–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah V, Alwassia H, Shah K, Yoon W, Shah P. Neonatal outcomes among multiple births </= 32 weeks gestational age: does mode of conception have an impact? A cohort study. BMC pediatrics. 2011;11:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turker G, Doger E, Arisoy AE, Gunlemez A, Gokalp AS. The effect of IVF pregnancies on mortality and morbidity in tertiary unit. Italian journal of pediatrics. 2013;39:17. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-39-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longo DR, Kruse RL, LeFevre ML, Schramm WF, Stockbauer JW, Howell V. An investigation of social and class differences in very-low birth weight outcomes: a continuing public health concern. Journal of health care finance. 1999;25:75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harteman JC, Groenendaal F, van Haastert IC, Liem KD, Stroink H, Bierings MB, et al. Atypical timing and presentation of periventricular haemorrhagic infarction in preterm infants: the role of thrombophilia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:140–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Leary H, Gregas MC, Limperopoulos C, Zaretskaya I, Bassan H, Soul JS, et al. Elevated cerebral pressure passivity is associated with prematurity-related intracranial hemorrhage. Pediatrics. 2009;124:302–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuzcu V, Nas S, Ulusar U, Ugur A, Kaiser JR. Altered heart rhythm dynamics in very low birth weight infants with impending intraventricular hemorrhage. Pediatrics. 2009;123:810–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell RB, Petrini JR, Damus K, Mattison DR, Schwarz RH. The changing epidemiology of multiple births in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;101:129–35. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Branum AM, Schoendorf KC. Changing patterns of low birthweight and preterm birth in the United States, 1981–98. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2002;16:8–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2002.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seifer DB, Frazier LM, Grainger DA. Disparity in assisted reproductive technologies outcomes in black women compared with white women. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1701–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seifer DB, Zackula R, Grainger DA. Trends of racial disparities in assisted reproductive technology outcomes in black women compared with white women: Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology 1999 and 2000 vs. 2004–2006. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:626–35. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujimoto VY, Luke B, Brown MB, Jain T, Armstrong A, Grainger DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in assisted reproductive technology outcomes in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:382–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]