Abstract

Botanicals possess numerous bioactivities, and some promote healthy aging. Dietary macronutrients are major determinants of life span. The interaction between botanicals and macronutrients that modulates life span is not well understood. Here, we investigated the effect of a cranberry-containing botanical on life span and the influence of macronutrients on the longevity-related effect of cranberry in Drosophila. Flies were supplemented with cranberry on three dietary conditions: standard, high sugar–low protein, and low sugar–high protein diets. We found that cranberry slightly extended life span in males fed with the low sugar–high protein diet but not with other diets. Cranberry extended life span in females fed with the standard diet and more prominently the high sugar–low protein diet but not with the low sugar–high protein diet. Life-span extension was associated with increased reproduction and higher expression of oxidative stress and heat shock response genes. Moreover, cranberry improved survival of sod1 knockdown and dfoxo mutant flies but did not increase wild-type fly’s resistance to acute oxidative stress. Cranberry slightly extended life span in flies fed with a high-fat diet. These findings suggest that cranberry promotes healthy aging by increasing stress responsiveness. Our study reveals an interaction of cranberry with dietary macronutrients and stresses the importance of considering diet composition in designing interventions for promoting healthy aging.

Key Words: Aging, Dietary intervention, Nutraceutical, Diet composition, Oxidative stress.

Adequate consumption of fruits and vegetables is critical in maintaining general health and reducing the incidence of diseases in humans (1). Botanicals or nutraceuticals made from various plant parts have been shown to possess numerous bioactivities that reduce inflammation, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and many other types of diseases (2,3). Some botanicals have been demonstrated to promote healthy aging in model organisms (4,5). To name a few, curcumin from turmeric and botanicals from blueberry can extend life span in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila, and botanicals from blueberry, strawberry, cranberry, and walnut can delay age-related decline of cognitive function in rodents (2,6–11). The health-promoting bioactivities of botanicals can be attributed to their high content of phytochemicals including proanthocyanidins (PACs) and flavonoids (3,12–14). However, most aging-intervention studies in model organisms have been conducted in animals under a single dietary condition, either a so-called standard diet or a high-fat diet. This limits the value of animal studies in help designing effective interventions with botanicals and pharmaceuticals for promoting healthy aging in humans because of the diverse dietary customs in humans.

Dietary macronutrients including protein, carbohydrate, and fat have a significant impact on health and life span (15). Excessive intake of any dietary macronutrient is generally detrimental to health, such as the increased risk of diabetes associated with excessive intake of sugar and/or fat (16). Dietary restriction (DR) without malnutrition is one of the most potent dietary interventions that can reliably extend health and life span in many model organisms (17,18). Increasing lines of evidences indicate that dietary macronutrient composition is more critical in determining life span than a single nutrient (15,19). For example, protein restriction without changing the content of carbohydrate can extend life span in Drosophila (20,21). However, the composition of protein and carbohydrate in the diet is more potent in modulating life span than any single nutrient content (20,21). Flies generally live longer under the high sugar–low protein diet than other diets (22). In the rhesus monkey, one study showed that dietary restriction extended life span, whereas another study showed that dietary restriction improved health but did not extend life span (23,24). The discrepancy was attributable to the difference in dietary macronutrient composition between these two studies (23). This further strengthens the notion that diet composition is a major determinant of life span. Given the importance of diet composition, it is possible that aging interventions, such as those using botanicals, can be influenced by dietary macronutrient composition.

Cranberry is a popularly consumed fruit containing high contents of bioactive phytochemicals that can provide many health benefits, such as antimicrobial infection and anticancer (13,25,26). Cranberry juice is well known to be effective in preventing urinary tract infection due to the unique antimicrobial activity of PACs present in cranberry (26). PAC-enriched cranberry extract can extend life span in C elegans likely through insulin-like signaling and osmotic stress response pathways (27). It remains to be determined whether cranberry can extend life span in other species. Here, we tested the prolongevity effect of cranberry in Drosophila. We also investigated the impact of dietary macronutrient composition on the effect of cranberry on life span and determined some of the molecular mechanisms underlying the prolongevity effect of cranberry. Our study demonstrates the critical role of diet composition in modulating the effect of cranberry on health and life span.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks and Culture

Wild-type Canton S strain, da-Gal4 (w1118; P{w[+mW.hs] = GAL4-da.G32},3) and UAS-sod1 inverted repeat (IR) (w 1; P{UAS-Sod1.IR}F103/SM5) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). The sod1RNAi or knockdown flies were generated as progeny from crossing UAS-sod1IR males with da-Gal4 virgin females as previously described (28,29). The dfoxo mutant stocks dfoxo 21 and dfoxo 25 for generation of loss-of-function dfoxo mutant were kindly provided by E. Hafen (30). Fly stocks were maintained on standard cornmeal agar medium in an environmental chamber set at 25°C ± 1°C, 60% ± 5% humidity, and a 12:12 hour light/dark cycle (31). Three isocaloric sugar–yeast (SY)-based diets without supplementation of cranberry were prepared as previously described (28). Briefly, the SY1:1 diet contained 10% sugar and 10% autolyzed yeast (MP Biochemicals, Solon, OH) by weight/volume, the SY1:9 contained 2% sugar and 18% yeast, and the SY9:1 diet had 18% sugar and 2% yeast. In addition, a high-fat diet was prepared by adding 2% (w/v) palmitic acid to the SY1:1 diet, as previously described (32). All diets contained 1.5% agar. To prepare cranberry supplemented diets, PAC-enriched cranberry extract was added to the aforementioned three SY diets to the final concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3% by weight/volume. The SY diets were cooled down to approximately 60°C before the cranberry extract was added. The cranberry extract was kindly provided by Decas Botanical Synergies (Carver, MA). The ingredients of this botanical were previously described (27).

Life-Span Assay

Life-span assay was performed, as previously described (28). Briefly, adult flies of mixed sex were collected within 24 hour after eclosion and transferred to the SY1:1 diet for mating for 24 hour. Flies were sorted out by sex, placed in SY1:1 vials each with approximately 20 male or female flies for another 24 hour. Flies were then transferred to different SY diets supplemented with and without cranberry. Subsequently, flies were transferred to vials with fresh food once every 2–3 days. Life span was measured by recording the number of dead flies at the time of transfer until all flies were dead. Each life-span measurement used approximately 100–200 flies in 6–8 vials and was repeated at least twice.

Food Intake Measurement

A modified capillary feeder method was used to measure food intake, as previously described (28,33). Briefly, two flies at 11 days old were housed in each capillary feeding chamber with a feeding capillary filled with a specified SY diet without agar, which was supplemented with or without 2% cranberry. Eight chambers were set up to make eight replicates per dietary condition. Two additional chambers with capillaries filled with the same diet but without flies were set up to account for evaporation of liquid food. Food intake was measured once every 24 hours for three constitutive days. Daily food intake was calculated by averaging food intake over the 3 days from eight replicates.

Locomotor Activity Assay

Spontaneous locomotor activity of flies in population was measured using the Drosophila Activity Monitoring System (Trikinetics, Waltham, MA) as previously described (34). Briefly, each glass activity tube (1cm in diameter and 7.5cm in length) in the Drosophila Activity Monitoring System contained 12 flies fed a specified SY diet. Locomotor activity was measured by recording the number of beam breaks every 20 seconds over a 24-hour period for three consecutive days. At the end of each 24-hour period, the assay was stopped to count the number of dead flies in each vial. By the end of the experiment, only one fly died in two SY1:1 vials and two SY1:9 vials, two flies died in one SY1:9 vial, and three flies died in one SY1:9 vial, whereas no flies died in the SY9:1 vial. Four activity tubes were set up as replicates for each dietary treatment. Locomotor activity was calculated by averaging the total number of beam breaks per fly per 24-hour period for each dietary treatment.

Egg Laying Assay

Adult flies of mixed sex were collected in the similar way as described in the life-span assay and mated on the SY1:1 diet for 24 hours. Five once-mated females were sorted out under light CO2 anesthesia and placed into a vial with the SY9:1 diet supplemented with or without 2% cranberry. Flies were then transferred to fresh food once every 24 hours, and the number of eggs in each vial was counted at each transfer until the flies reached the age of 30 days old. The number of dead flies was also recorded if there were any. Total egg laying per fly in each vial was calculated by dividing the total number of eggs by the initial population of five flies at the age of 5–30 days. The egg counting was stopped at Day 30 because there are fewer than one egg laying per fly under the 9:1 diet without cranberry for five consecutive days after the flies reached 25 days old. The eggs laid by flies on the SY1:1 diet and on the first day on the SY9:1 diet were not counted in order to minimize the confounding factor of the SY1:1 diet on reproduction. Daily egg laying per fly was calculated by dividing the number of daily egg laying by the number of survived flies in each vial. Six vials with the total number of 30 flies were set up as replicates for each of the control and cranberry diets. Four out of the total 30 flies died by the end of experiment in the control vials and three out of 30 flies died in the cranberry treatment.

Oxidative Stress Assay

Acute oxidative stress resistance was measured by challenging flies with 20mM paraquat. Adult female flies were fed with the SY diets supplemented with and without 2% cranberry until they reached the age of 14 days old. Flies were then transferred into vials containing 20mM paraquat in 5% sucrose solution on 22-mm Whatman 3M filter discs. The number of dead flies was recorded once every 12 hours. Each vial had approximately 20 flies. Flies were set up as replicates in 6–10 vials for each dietary condition.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Flies were treated with the SY9:1 diet supplemented with and without 2% cranberry until they reached 14 days old. Total RNA was isolated from fly heads using the Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed as previously described (28) using the Step-One plus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The relative mRNA level of each gene was normalized to rp49 using Step-One Software version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems). Each polymerase chain reaction assay was performed with 5–6 independent biological replicates.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using StatView version 5.0 software (SAS, Cary, NC). Mantel–Cox log-rank tests were performed for life-span data by comparing cranberry-fed flies to those fed with the nonsupplemented control diet. Student’s t-test analyses were performed for all other measurements. Maximum life span was calculated from the 10% longest surviving flies. Values for mean and maximum life span, food intake, locomotion, and polymerase chain reaction are expressed as means ± standard error. p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cranberry Supplementation Extends Life Span in Drosophila

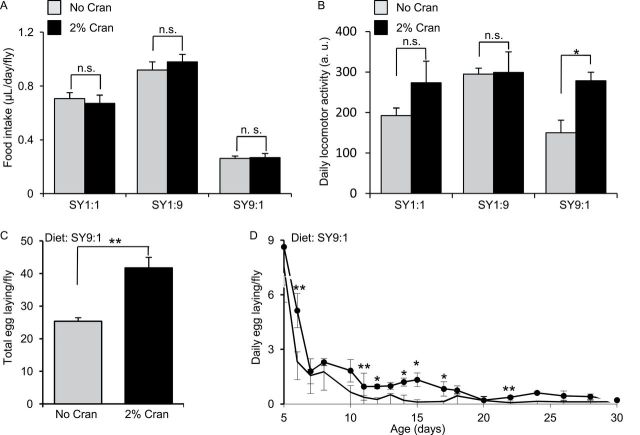

To determine the effect of cranberry supplementation on life span, we fed wild type Canton S flies with SY1:1 diet supplemented with a PAC-enriched cranberry extract. The SY1:1 diet contains 10% sugar and 10% yeast and is commonly used for life-span assays (35,36). We found that cranberry supplementation at 2%, but not 1%, slightly extended life span of female flies by approximately 10% relative to the nonsupplemented SY diet–matched controls (p < .001; Figure 1A, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1). However, cranberry supplementation at 2% did not affect life span of male flies fed with the SY1:1 diet (Figure 1B, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1). We did not observe life-span extension in male flies even when we increased cranberry supplementation to 3% under the SY1:1 diet (Figure 1B and Table 1). To determine whether life-span extension induced by cranberry is due to the effect of cranberry on food intake, we measured food intake of flies fed with the SY1:1 diet supplemented with and without 2% cranberry. Cranberry at 2% had no or little impact on daily food intake of female flies under the SY1:1 dietary condition (Figure 2A). We further assessed the impact of cranberry supplementation on locomotor activity as a parameter of general health. Cranberry supplementation at 2% had no significant effect on daily locomotor activity (Figure 2B). These findings indicate that the effect of cranberry supplementation on life span depends on gender and the dose of cranberry.

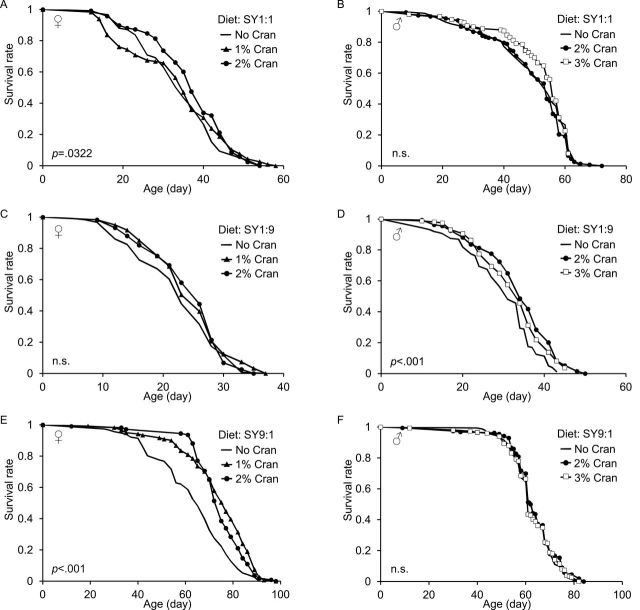

Figure 1.

Life-span extension induced by cranberry depends on dietary macronutrient composition. (A, C, and E) Life span of female flies fed with the standard SY1:1, the low sugar–high protein SY1:9, and the high sugar–low protein SY9:1 diets, respectively, supplemented with 0%, 1%, and 2% cranberry extract. (B, D, and F) Life span of male flies fed with the SY1:1, SY1:9, and SY9:1 diets, respectively, supplemented with 0%, 2%, and 3% cranberry extract. Life span of more than 100 flies was measured in each life-span assay, which was repeated at least twice. Representative life-span curves are shown in this figure. SY, sugar and autolyzed yeast diet; Cran, cranberry; n.s., not significant. The p values were calculated by log-rank test by comparing male and female flies fed with the 2% or 3% cranberry supplemented diet to gender-matched and SY diet–matched nonsupplemented controls. The p values are based on log-rank test.

Table 1.

Life Span of Flies Fed Diets Supplemented With and Without Cranberry Extract

| Strain | Gender | SY Diet* | Cranberry Concentration | Number of Flies | Mean Life Span (days ± SE) | Mean Life Span Change | p Value for All Flies† | Max. Life Span (days ± SE)‡ | p Value for Top 10% Flies§ |

| Canton S | Female | SY 1:1 | 0% | 117 | 34.0±0.9 | 50.1±1.0 | |||

| 1% | 117 | 33.5±1.1 | −1.5% | 0.3738 | 52.4±0.9 | 0.1018 | |||

| 2% | 118 | 36.8±0.9 | 8.2% | 0.0322 | 50.6±0.7 | 0.9468 | |||

| SY 1:9 | 0% | 121 | 22.6±0.6 | 33.3±0.3 | |||||

| 1% | 121 | 24.4±0.6 | 8.0% | 0.0896 | 35.2±0.4 | 0.0086 | |||

| 2% | 117 | 24.2±0.6 | 7.1% | 0.2294 | 32.5±0.6 | 0.323 | |||

| SY 9:1 | 0% | 116 | 62.8±1.5 | 86.2±1.1 | |||||

| 1% | 121 | 73.4±1.4 | 16.9% | <.0001 | 91.4±0.7 | 0.0021 | |||

| 2% | 109 | 73.7±1.1 | 17.4% | <.0001 | 90.8±1.0 | 0.0262 | |||

| Male | SY 1:1 | 0% | 158 | 49.5±1.1 | 62.2±0.4 | ||||

| 2% | 152 | 49.1±1.1 | −0.8% | 0.3773 | 63.1±0.8 | 0.3769 | |||

| 3% | 150 | 51.8±1.0 | 4.6% | 0.5549 | 63.1±0.7 | 0.287 | |||

| SY 1:9 | 0% | 160 | 29.5±0.7 | 35.2±1.9 | |||||

| 2% | 134 | 33.8±0.8 | 14.6% | <.0001 | 46.6±0.7 | <.0001 | |||

| 3% | 160 | 32.7±0.7 | 10.8% | 0.0002 | 46.0±0.6 | <.0001 | |||

| SY 9:1 | 0% | 153 | 62.9±0.7 | 73.5±0.6 | |||||

| 2% | 156 | 63.2±0.8 | 0.5% | 0.2046 | 78.9±1.0 | <.0001 | |||

| 3% | 149 | 62.4±0.8 | −0.8% | 0.5916 | 77.8±0.7 | 0.0005 | |||

| sod1RNAi | Female | SY 1:1 | 0% | 98 | 21.8±1.2 | 29.7±1.3 | |||

| 2% | 94 | 27.8±1.5 | 27.5% | <.0001 | 40.1±1.5 | 0.0005 | |||

| Female | SY 1:9 | 0% | 101 | 11.6±0.3 | 17.7±0.7 | ||||

| 2% | 95 | 16.7±0.4 | 44.0% | <.0001 | 23.4±0.3 | <.0001 | |||

| Female | SY 9:1 | 0% | 93 | 36.2±1.1 | 55.33±1.1 | ||||

| 2% | 89 | 49.3±1.5 | 36.2% | <.0001 | 78.6±2.5 | <.0001 | |||

| dfoxo − /− | Female | SY 9:1 | 0% | 153 | 38.4±1.2 | 61.4±0.8 | |||

| 2% | 157 | 53.4±1.0 | 39.1% | <.0001 | 67.9±0.4 | <.0001 | |||

| Canton S | Female | High fat | 0% | 116 | 27.4±0.7 | 40.9±0.6 | |||

| 2% | 116 | 29.4±0.8 | 7.3% | 0.036 | 42.0±08 | 0.2009 |

Notes: p Values <.05 are italicized and bolded. *SY refers to sugar–yeast diet.

† p Value was calculated by log-rank analysis for life span of all flies.

‡Maximum (Max.) life span was based on life span of the top 10% longest lived flies.

§ p Value was calculated by log-rank analysis for the top 10% longest lived flies.

Figure 2.

The effects of cranberry supplementation on food intake and locomotor activity. (A) Food intake of females flies fed with the standard SY1:1, the low sugar–high protein SY1:9, and the high sugar–low protein SY9:1 diets, respectively, supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry extract. (B) Locomotor activity of females flies fed with the standard SY1:1, the low sugar–high protein SY1:9, and the high sugar–low protein SY9:1 diets, respectively, supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry extract. Each bar graph was generated from at least six biological replicate samples. Error bars indicate standard errors. SY, sugar–yeast diet; n.s., not significant. *p < .05; **p < .01 by Student’s t test.

Diet Composition Influences the Effect of Cranberry on Life Span

Because dietary macronutrients are major determinants of life span (15), we investigated how diet composition influences the effect of cranberry supplementation on life span. To this end, we selected two additional SY diets that have the same amount of total sugar and yeast as the SY1:1 diet but contain different sugar-to-yeast ratio. One diet has a low sugar-to-yeast ratio at 1:9 and the other has a high sugar-to-yeast at 9:1, which are called the SY1:9 and SY9:1 diet, respectively. These three diets are isocaloric because sugar and autolyzed yeast have similar calorie content by weight. Consistent with published data, both male and female flies had a shorter life span under the SY1:9 diet compared with the SY1:1 diet (4). Cranberry supplementation at 2% and 3% slightly extended life span of male flies by 14.6% and 10.8%, respectively, under the SY1:9 diet relative to the diet-matched nonsupplemented controls (Figure 1D, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1). Cranberry supplementation at either 1% or 2% had no or little effect on life span of female flies fed with the SY1:9 diet (Figure 1C, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1).

Both male and female flies have a longer life span under the high sugar-to-yeast SY9:1 diet relative to the SY1:1 diet (28). Cranberry supplementation at either 2% or 3% did not extend life span of male flies fed with the SY9:1 diet relative to the nonsupplemented controls (Figure 1F, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1). However, cranberry supplementation at either 1% or 2% significantly increased life span in female flies fed with the SY9:1 diet by approximately 17% relative to the nonsupplemented controls (Figure 1E, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1). These findings suggest that the prolongevity effect of cranberry depends on diet composition.

Cranberry Supplementation Can Improve Locomotor Activity and Reproductive Output

Because cranberry supplementation extended life span of females under both SY1:1 and SY9:1 diets, we focused on females in our studies of the mechanisms underlying the prolongevity effect of cranberry. As in the case of the SY1:1 diet, cranberry supplementation at 2% had no or little effect on daily food intake of females under the SY1:9 and SY9:1 diets relative to the diet-matched nonsupplemented controls (Figure 2A). Cranberry had no or little effect on daily locomotor activity of females fed with the SY1:9 diet either (Figure 2B). However, cranberry supplementation significantly increased daily locomotor activity of females fed with the SY9:1 diet (Figure 2B). The locomotor activity of females fed with the SY9:1 diet without cranberry was not significantly different from that of females fed with the SY1:1 diet without cranberry (Figure 2B, p = .286). We also measured reproductive output as another health span parameter for flies fed with the SY9:1 diet with and without 2% cranberry. Cranberry supplementation significantly increased the total number of egg laying by flies at the adult age of 5–30 days by approximately 60% relative to the control (Figure 2C). Flies on the cranberry diet also had a higher number of daily egg laying than the control flies (Figure 2D). These findings suggest that cranberry supplementation can improve general health in females.

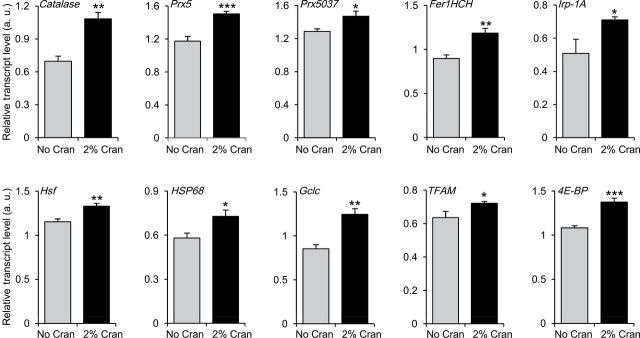

Cranberry Supplementation Induces Expression of Stress Response Genes

To determine the molecular mechanisms by which cranberry extends life span, we measured expression changes for 35 aging-related genes under the SY9:1 diet. Cranberry supplementation had no or minor effect on the transcript levels of most of these genes (Supplementary Table S2). However, we found that cranberry supplementation increased transcript levels of several genes involved in stress response pathways, including oxidative stress–related genes catalase, peroxiredoxin 5 (Prx5), Prx5037, ferritin 1 heavy chain homologue (Fer1HCH), iron regulatory protein 1A (Irp-1A) and glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (Gclc), heat shock response genes heat shock factor (Hsf) and heat shock protein 68 (Hsp68), mitochondrial biogenesis gene TFAM, and a target of rapamycin pathway gene 4E-BP (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S1; gene information can be found at http://www.flybase.org). These results suggest that life-span extension induced by cranberry is associated with changes in genes involved in the redox system in female flies.

Figure 3.

The effect of cranberry supplementation on expression of aging-related genes. Shown in this figure are the transcript levels of 10 aging-related genes in the heads of female flies fed with the high sugar–low protein SY9:1 diet supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry. Each bar graph was generated from five to six biological replicate samples. Error bars indicate standard errors. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 by Student’s t test. SY, sugar–yeast diet.

Cranberry Supplementation Improves Survival of sod1 Mutant Flies

To further investigate the effect of cranberry on stress resistance, we first tested the effect of cranberry supplementation on fly resistance to paraquat-induced acute oxidative stress. Cranberry supplementation at 2% had no or little impact on female flies’ resistance to paraquat under either the SY1:1 or SY9:1 diet relative to the diet-matched nonsupplemented controls (Figure 4A and B). We then tested the effect of cranberry supplementation on the survival of sod1 knockdown mutant (sod1RNAi) female flies. The sod1RNAi flies are known to accumulate higher oxidative damage with age than wild-type flies (37). Cranberry supplementation at 2% significantly extended the mean life span of female sod1RNAi flies under the SY1:1, SY1:9, and SY9:1 diets by 27.5%, 44.0%, and 36.2%, respectively, relative to the diet-matched nonsupplemented controls (Figure 4C–E, Table 1, and Supplementary Table S1). These findings suggest that cranberry supplementation can improve the survival of chronically oxidative stressed flies although it is not sufficient to increase fly resistance to acute oxidative stress.

Figure 4.

The effect of cranberry supplementation on oxidative damage. (A and B) The survival rate of female flies under the challenge of 20mM paraquat after flies were fed with the SY1:1 and SY9:1 diet supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry. (C and D) Life-span curve of sod1 knockdown mutant females fed with the SY1:1 and SY9:1 diet supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry. SY, sugar–yeast diet; n.s., not significant. The p values are based on log-rank test.

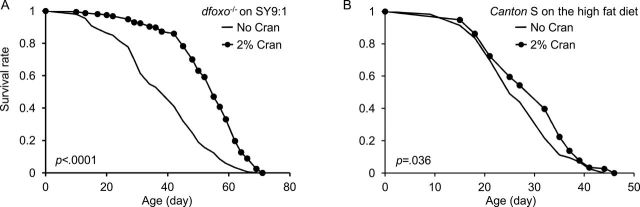

Cranberry Supplementation Improves Survival of dfoxo Mutant Flies and Flies Fed a High-Fat Diet

Considering that cranberry extends life span of females fed with the high sugar–low protein diet, we investigated whether dFOXO, a downstream target of glucose sensing insulin-like signaling (30), is required for life-span extension induced by cranberry. To this end, we fed dfoxo loss-of-function mutant (dfoxo 21/25) females with the SY9:1 diet supplemented with 2% cranberry. We found that cranberry supplementation at 2% increased life span of dfoxo 21/25 by 39.1% under the SY9:1 diet (Figure 5A and Table 1). To further investigate the impact of cranberry supplementation on metabolic health of flies, we fed 2% cranberry to wild-type Canton S female flies fed with the high-fat diet that contained 2% palmitic acid, a common saturated fat. Cranberry supplementation at 2% slightly increased survival of female flies under the high-fat diet by 7.3% (Figure 5 and Table 1). These findings suggest that cranberry can alleviate detrimental effects induced by dfoxo mutation and a high-fat diet.

Figure 5.

The effect of cranberry supplementation on metabolism. (A) Life span of dfoxo − /− mutant female flies fed with the high sugar–low protein SY9:1 diet supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry. (B) Life span of wild-type Canton S female flies fed a high-fat diet supplemented with 0% and 2% cranberry. The p values are based on log-rank test. SY, sugar–yeast diet.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effect of cranberry supplementation on life span of flies under three dietary conditions: standard, low sugar–high protein and high sugar–low protein diets. Two major findings emerged from this study, which have significant implications for aging interventions with botanicals. First, we have previously shown that cranberry supplementation can extend life span in C. elegans and delay age-related functional decline of pancreatic β-cells in rats (27,38). Here, we demonstrated that cranberry supplementation can extend life span in Drosophila. Moreover, cranberry supplementation can increase both locomotor activity and reproductive output, two health span–related parameters, in female flies. These studies indicate that the effect of cranberry in promoting healthy aging is conserved in diverse model organisms. Second, we found that life-span extension induced by cranberry depends on gender and diet composition. Cranberry supplementation is most effective in extending life span of female flies under the high sugar–low protein diet compared with female flies under other dietary conditions and also male flies under all dietary conditions tested here. It is noteworthy to point out that flies live longest under the high sugar–low protein diet than those on the other two diets tested here, suggesting that cranberry supplementation does not simply compensate for any detrimental effects of dietary macronutrients. The gender-dependent and diet composition–dependent features of cranberry supplementation appear to be common among aging interventions with botanicals and pharmaceuticals. To name a few examples, resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound rich in grapes and some other plants, can improve survival of mice under a high-fat diet but not the standard rodent diet (39,40). Freeze-dried açai pulp can increase the survival only in female flies under a high-fat diet but not the standard diet (41). A botanical made from a mixture of oregano and cranberry extends the life span only in female Mexican fruit flies (Mexfly) under the standard and the high sugar–low protein Mexfly diet but not the low sugar–high protein diet (42). The different response of male and female flies to cranberry supplementation may be due to different physiology in males and females. Together our findings suggest that dietary macronutrient composition has a significant impact on the effect of botanicals and pharmaceuticals on life span. Our study also stresses that it is critical to take diet composition into consideration when designing aging interventions, especially in human populations, which have diverse dietary customs.

We found that cranberry supplementation was not sufficient to extend the life span of female flies fed with the low sugar–high protein diet. The low sugar–high protein diet is known to induce chronic dehydration stress in Drosophila (43,44). Therefore, the lack of life-span extension induced by cranberry in flies fed with the SY1:9 diet may be due to the possibility that these flies die of dehydration stress. Cranberry supplementation may not be sufficient to alleviate dehydration stress. Food intake results indicated that flies on the SY1:9 diet had higher food intake in volume than those on the SY1:1 and SY9:1 diets. Therefore, another explanation for the absence of life-span extension in flies fed with the SY1:9 diet would be that these flies ingest too much cranberry, which may cause detrimental effects and cancel out any beneficial effects of cranberry. However, both scenarios are unlikely the case. Firstly, flies fed with the SY1:9 diet supplemented with 1% cranberry do not necessarily ingest more cranberry than flies fed with the SY1:1 diet supplemented with 2% cranberry, the latter of which live longer than the diet-matched controls. This suggests that any possible cranberry toxicity does not contribute substantially to the lack of life-span extension under the SY1:9 diet. Secondly, cranberry supplementation can promote the survival of sod1 knockdown flies under all three dietary conditions regardless of any possible dehydration stress and food intake. These suggest that dehydration stress and cranberry overdose do not likely confound the fly response to diet composition.

Although reproduction is not a strong predictor of life span, there is some trade-off between life span and reproduction (45,46). Therefore, it is possible that life-span extension induced by cranberry is associated with reduced reproduction. However, we have found that cranberry supplementation significantly increases reproductive output. This suggests that cranberry supplement promote longevity without reproduction trade-off.

Many botanical phytochemicals including PACs have high levels of antioxidant activity, which some investigations have used to explain the numerous health benefits attributable to these compounds (3,13). Cranberry ranks among the top fruits and vegetables that have high antioxidant activities indicated by high oxygen radical absorbance capacity values (47–49). It is therefore reasonable to assume that the prolongevity effect of cranberry is primarily due to its antioxidant activity. However, we found that cranberry supplementation did not increase resistance to paraquat-induced acute oxidative stress in Drosophila. This is consistent with our previous study showing that cranberry supplementation did not increase worm resistance to acute oxidative stress (27). However, we should point out that paraquat is known to decrease food intake and, therefore, the parameter of paraquat resistance may reflect resistance to a combination of oxidative and starvation stress (33). We have not tested the effect of cranberry supplementation on fly starvation resistance yet. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that phytochemicals, primarily PACs, in cranberry are not necessarily strong antioxidants in vivo. It is unlikely that cranberry promotes healthy aging mainly through their direct reactive oxygen species scavenging activities. However, we have found that cranberry supplementation improves survival of sod1 knockdown mutant flies, which chronically accumulate oxidative damage and are sensitive to oxidative stress. One possible explanation for this observation is that cranberry does have direct antioxidant activity in vivo but is more effective against chronic oxidative damage as opposed to the acute stress involved in paraquat studies. An alternative explanation would be that cranberry acts indirectly to increase animal resistance to oxidative stress by inducing expression of stress response genes. Both scenarios are likely explanations for the promotion of healthy aging by cranberry. However, we prefer the idea that the second scenario is more effective than the first one. This preference is supported by our previous and current studies showing that cranberry supplementation induces expression of genes involved in ROS scavenging and heat shock response in both C. elegans and Drosophila (27). Cranberry supplementation generally extends the life span of the short-lived and oxidative stressed flies, such as sod1 knockdown and dfoxo mutant flies, better than the wild-type Canton S flies. These findings suggest that cranberry promotes healthy aging at least partially by inducing stress response pathways.

Cranberry consumption has been shown to improve metabolic profiles, such as inducing favorable glycemic response by blunting the increase of postprandial plasma glucose levels in humans (49,50). We have previously shown that cranberry supplementation requires DAF-16, a forkhead transcription factor downstream of the insulin-like signaling, to extend life span in C. elegans (27). Cranberry does not further extend life span of long-lived insulin-like signaling mutants, such as daf-2 and age-1, in C. elegans (27). Insulin or insulin-like signaling is a major pathway involved in glucose metabolism (51). The findings from studies in humans and worms suggest that cranberry supplementation modulates insulin or insulin-like signaling to promote healthy aging. This conclusion is consistent with our findings that cranberry can extend life span of flies under the high sugar-low protein diet. However, we have found that cranberry does not require dFOXO, a fly forkhead transcript factor (30), to promote longevity in Drosophila, suggesting that dFOXO is either not the target or not the only target of cranberry action. In addition, we have previously demonstrated that cranberry-induced life-span extension also requires osmotic stress response in C elegans (27). Together these findings suggest that cranberry supplementation modulates multiple signaling pathways to promote healthy aging.

Cranberry is a popularly consumed fruit that is known to confer to humans many health benefits (3). Our study strengthens the view that cranberry has antiaging properties. Furthermore, our study reveals that there is an interaction of cranberry with dietary macronutrients in modulating life span. This study should provide insight for the design of effective interventions with cranberry and other botanicals for promoting healthy aging in humans.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (Z01-AG000366-06 to S.Z).

Acknowledgment

We thank Decas Botanical Synergies Inc. for the cranberry extract, E. Hafen for dfoxo strains, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for other fly stocks. We thank Edward Spangler for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Liu RH. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(3 suppl):517S–520S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joseph JA, Shukitt-Hale B, Lau FC. Fruit polyphenols and their effects on neuronal signaling and behavior in senescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:470–485 doi:1100/1/470 [pii] 10.1196/annals.1395.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seeram NP. Berry fruits: compositional elements, biochemical activities, and the impact of their intake on human health, performance, and disease. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:627–629 doi:10.1021/jf071988k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dong Y, Guha S, Sun X, Cao M, Wang X, Zou S. Nutraceutical interventions for promoting healthy aging in invertebrate models. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:718491 doi:10.1155/2012/718491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lucanic M, Lithgow GJ, Alavez S. Pharmacological lifespan extension of invertebrates. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:445–458 doi:10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee KS, Lee BS, Semnani S, et al. Curcumin extends life span, improves health span, and modulates the expression of age-associated aging genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13:561–570 doi:10.1007/s11357-012-9438-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shen LR, Xiao F, Yuan P, et al. Curcumin-supplemented diets increase superoxide dismutase activity and mean lifespan in Drosophila. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:1133–1142 doi:10.1007/s11357-012-9438-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alavez S, Vantipalli MC, Zucker DJ, Klang IM, Lithgow GJ. Amyloid-binding compounds maintain protein homeostasis during ageing and extend lifespan. Nature. 2011;472:226–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peng C, Zuo Y, Kwan KM, et al. Blueberry extract prolongs lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:170–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilson MA, Shukitt-Hale B, Kalt W, Ingram DK, Joseph JA, Wolkow CA. Blueberry polyphenols increase lifespan and thermotolerance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2006;5:59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willis LM, Shukitt-Hale B, Cheng V, Joseph JA. Dose-dependent effects of walnuts on motor and cognitive function in aged rats. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:1140–1144 doi:10.1017/S0007114508059369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vinson JA, Su X, Zubik L, Bose P. Phenol antioxidant quantity and quality in foods: fruits. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5315–5321 jf0009293 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu RH. Potential synergy of phytochemicals in cancer prevention: mechanism of action. J Nutr. 2004;134(12 suppl):3479S–3485S 134/12/3479S [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neto CC. Cranberry and its phytochemicals: a review of in vitro anticancer studies. J Nutr. 2007;137(1 suppl):186S–193S 137/1/186S [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Piper MD, Partridge L, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ. Dietary restriction and aging: a unifying perspective. Cell Metab. 2011;14:154–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:790–797 doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ingram DK, Zhu M, Mamczarz J, et al. Calorie restriction mimetics: an emerging research field. Aging Cell. 2006;5:97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span–from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D, Charleston MA, Clissold FJ. Modelling nutritional interactions: from individuals to communities. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:53–60 doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee KP, Simpson SJ, Clissold FJ, et al. Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: new insights from nutritional geometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2498–2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skorupa DA, Dervisefendic A, Zwiener J, Pletcher SD. Dietary composition specifies consumption, obesity, and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2008;7:478–490 doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00400.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruce KD, Hoxha S, Carvalho GB, et al. High carbohydrate-low protein consumption maximizes Drosophila lifespan. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1129–1135 doi:10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mattison JA, Roth GS, Beasley TM, et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature. 2012;489:318–321 doi:10.1038/nature11432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2009;325:201–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neto CC, Amoroso JW, Liberty AM. Anticancer activities of cranberry phytochemicals: an update. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52(suppl 1):S18–S27 doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Howell AB. Bioactive compounds in cranberries and their role in prevention of urinary tract infections. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51:732–737 doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guha S, Cao M, Kane RM, Savino AM, Zou S, Dong Y. The longevity effect of cranberry extract in Caenorhabditis elegans is modulated by daf-16 and osr-1. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:1559–1574 doi:10.1007/s11357-012-9459-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun X, Komatsu T, Lim J, et al. Nutrient-dependent requirement for SOD1 in lifespan extension by protein restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2012;11:783–793 doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00842.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abrahamson JL, Baker LG, Stephenson JT, Wood JM. Proline dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli K12. Properties of the membrane-associated enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1983;134:77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jünger MA, Rintelen F, Stocker H, et al. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J Biol. 2003;2:20 doi:10.1186/1475-4924-2-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ashburner M, Golic KG, Hawley RS, eds. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. Woodbury, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boyd O, Weng P, Sun X, et al. Nectarine promotes longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1669–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ja WW, Carvalho GB, Mak EM, et al. Prandiology of Drosophila and the CAFE assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8253–8256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laslo M, Sun X, Hsiao CT, Wu WW, Shen RF, Zou S. A botanical containing freeze dried açai pulp promotes healthy aging and reduces oxidative damage in sod1 knockdown flies. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:1117–1132 doi:10.1007/s11357-012-9437-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mair W, Goymer P, Pletcher SD, Partridge L. Demography of dietary restriction and death in Drosophila. Science. 2003;301:1731–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mair W, Sgrò CM, Johnson AP, Chapman T, Partridge L. Lifespan extension by dietary restriction in female Drosophila melanogaster is not caused by a reduction in vitellogenesis or ovarian activity. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1011–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Missirlis F, Hu J, Kirby K, Hilliker AJ, Rouault TA, Phillips JP. Compartment-specific protection of iron-sulfur proteins by superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47365–47369 doi:10.1074/jbc.M307700200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu M, Hu J, Perez E, et al. Effects of long-term cranberry supplementation on endocrine pancreas in aging rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1139–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pearson KJ, Baur JA, Lewis KN, et al. Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Metab. 2008;8:157–168 doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sun X, Seeberger J, Alberico T, et al. Açai palm fruit (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) pulp improves survival of flies on a high fat diet. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zou S, Carey JR, Liedo P, Ingram DK, Yu B, Ghaedian R. Prolongevity effects of an oregano and cranberry extract are diet dependent in the Mexican fruit fly (Anastrepha ludens). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ja WW, Carvalho GB, Zid BM, Mak EM, Brummel T, Benzer S. Water- and nutrient-dependent effects of dietary restriction on Drosophila lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18633–18637 doi:10.1073/pnas.0908016106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dick KB, Ross CR, Yampolsky LY. Genetic variation of dietary restriction and the effects of nutrient-free water and amino acid supplements on lifespan and fecundity of Drosophila. Genet Res (Camb). 2011;93:265–273 doi:10.1017/S001667231100019X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carey JR, Harshman LG, Liedo P, Müller HG, Wang JL, Zhang Z. Longevity-fertility trade-offs in the tephritid fruit fly, Anastrepha ludens, across dietary-restriction gradients. Aging Cell. 2008;7:470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Drenos F, Kirkwood TB. Modelling the disposable soma theory of ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gu L, Kelm MA, Hammerstone JF, et al. Concentrations of proanthocyanidins in common foods and estimations of normal consumption. J Nutr. 2004;134:613–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. White BL, Howard LR, Prior RL. Polyphenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of extruded cranberry pomace. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:4037–4042 doi:10.1021/jf902838b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vinson JA, Bose P, Proch J, Al Kharrat H, Samman N. Cranberries and cranberry products: powerful in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo sources of antioxidants. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:5884–5891 doi:10.1021/jf073309b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wilson T, Singh AP, Vorsa N, et al. Human glycemic response and phenolic content of unsweetened cranberry juice. J Med Food. 2008;11:46–54 doi:10.1089/jmf.2007.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marshall S. Role of insulin, adipocyte hormones, and nutrient-sensing pathways in regulating fuel metabolism and energy homeostasis: a nutritional perspective of diabetes, obesity, and cancer. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]