Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the feasibility of an age-adapted, manualized behavioral treatment for geriatric hoarding.

Methods

Participants were 11 older adults (mean age: 66 years) with hoarding disorder. Treatment encompassed 24 individual sessions of psychotherapy that included both cognitive rehabilitation targeting executive functioning and exposure to discarding/not acquiring. Hoarding severity was assessed at baseline, mid-treatment, and posttreatment.

Results

Results demonstrated clinically and statistically significant changes in hoarding severity at posttreatment. No participants dropped out of treatment. Eight participants were classified as treatment responders, and three as partial responders. Partial responders reported severe/extreme hoarding and psychiatric comorbidities at baseline.

Conclusions

The combination of cognitive rehabilitation and exposure therapy is a promising approach in the treatment of geriatric hoarding. Targeting neurocognitive deficits in behavioral therapy for these geriatric patients with hoarding disorder doubled response rates relative to our previous trial of cognitive behavior therapy alone.

Keywords: CBT, cognitive remediation, hoarding, older adults, OCD

Hoarding disorder (HD) in older adulthood is a potentially debilitating psychiatric condition with significant health implications.1 Clinically significant hoarding is defined as: 1) the acquisition of and failure to discard a large number of possessions that appear (to others) to be useless or of limited value; 2) living or work spaces sufficiently cluttered that they preclude activities for which those spaces were designed; and 3) significant distress or impairment in functioning caused by the hoarding behavior or clutter.2 HD is common, with prevalence estimates at approximately 5.3%.3 It is unclear if the prevalence rates increase with age; one study found that hoarding symptoms were three times more prevalent in older adults compared with younger adults,3 but this finding has not been substantiated by other investigations.4–6 Furthermore, it is uncertain if the hoarding symptoms are progressive in older adulthood7 or stabilize in midlife.8 Given age-related physical and cognitive changes, hoarding is particularly dangerous in late life due to increased risk of falls, fire hazards, poor nutrition, and health/medication mismanagement.1 To date, standard cognitive behavioral treatments for late-life hoarding have not proven to be effective.9,10 The current report presents the results of an open trial of a novel treatment approach targeting the neurocognitive deficits and geriatric-specific aspects of late-life HD, as well as its core symptoms.

There are a small number of late-life HD case studies and series in the literature11 and one open trial.9 In the open trial, Ayers et al. found considerably low response rates (18%–20%) for individual cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in geriatric HD participants. Of 12 geriatric participants treated with manualized CBT for hoarding, only 3 of the 12 were categorized as treatment responders at posttreatment, and none met criteria for treatment response at the 6-month follow-up. In a qualitative exploration of therapist and patient perspectives on treatment using the same sample,10 the therapist observed that executive functioning deficits (planning, problem solving, cognitive flexibility, and prospective memory) negatively affected treatment response. Participants also reported that cognitive restructuring strategies, which may place greater demands on executive functioning, had limited utility. These findings are supported by evidence that poor executive functioning (e.g., planning, categorization, decision making, working memory, cognitive flexibility) are characteristic of HD across the lifespan.12–15 Neurocognitive impairment is associated with poorer response to CBT in other geriatric psychiatric populations,16 which may explain the poor outcomes seen with CBT in geriatric hoarding participants.9,10

Taken together, these findings suggest that adding cognitive rehabilitation interventions to CBT for HD in older adults may enhance treatment response. We developed a novel intervention designed to compensate for cognitive deficits or weaknesses, particularly executive dysfunction. In this investigation, cognitive rehabilitation was combined with behavioral therapy, which promotes habituation to distress caused by discarding or not acquiring possessions. We hypothesized that older adults with HD would show clinically and statistically significant decreases in hoarding severity after this novel treatment.

METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review board at VA San Diego Healthcare System and the University of California, San Diego.

Participants

Participants were recruited from posted flyers throughout San Diego County. Inclusion criteria were: 1) age 60 years or older; 2) an HD diagnosis according to the proposed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, diagnostic criteria,2 confirmed at a consensus conference including at least two licensed professionals with expertise in hoarding; 3) a score ≥20 on the UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale17 (UHSS); and 4) a score ≥40 on the Savings Inventory–Revised (SI-R).18 Exclusion criteria included a score ≤24 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment,19 active substance use disorders, psychotic disorders, bipolar I or II disorder, and current participation in other psychotherapy. Participants were required to remain on stable doses of any psychiatric medications, with no changes for at least 3 months before the baseline assessment and throughout the course of treatment.

Measures

The following measures were used: 1) the Montreal Cognitive Assessment as a gross screen of cognitive abilities; 2) the Hoarding Rating Scale20 as a screening tool for hoarding symptoms when presenting for evaluation; 3) the Mini–International Neuropsychiatric Interview21 as a brief diagnostic interview; 4) the SI-R as a self-report measure used to assess hoarding severity; 5) the UHSS as a clinician-administered scale that measures the severity of hoarding; 6) the Clutter Image Rating Scale22 (CIR) as a self-report measure of level of clutter in the home; 7) the Clinical Global Impression23 (CGI) severity and improvement scales to judge overall severity of illness and global response to treatment; and (8) the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale24 to measure anxiety and depression symptoms. An advanced level graduate student and a licensed clinical psychologist administered all measures. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Hoarding Rating Scale were used only for prescreening. All other measures were administered at baseline and post-assessment. The SI-R and UHSS were also administered midtreatment. Intraclass correlations for randomly selected UHSS total scores were high (0.85). Treatment fidelity, as measured by the first author (C.A.) using a content-based adherence and competency manual, was high (all >95%) on 15% of therapist video tapes randomly selected for fidelity rating. Classification as a treatment responder required: 1) a 35% reduction in both primary outcome measures (SI-R and UHSS) of hoarding severity;25 and 2) a 2 (much improved) or better score on the CGI improvement scale.

Cognitive Rehabilitation and Behavior Therapy for HD

Each participant was seen in-person for 24 one-hour sessions of individual psychotherapy by 1 of 3 licensed clinical psychologists. Therapy sessions were held twice per week for the first 6 weeks, then once per week for 8 weeks, and then every other week for 8 weeks. Treatment was more intensive during the initial phase of treatment in an effort to build skills necessary to complete homework assignments. The manualized intervention included cognitive rehabilitation sessions targeting prospective memory (e.g., calendar use, to-do lists, prioritizing) and categorization/organization, problem solving, and cognitive flexibility (first six sessions). These modules were adapted for geriatric HD from the Compensatory Cognitive Training manual for people with psychosis.26 The remaining sessions focused on behavioral therapy for discarding and acquiring (16 sessions), followed by relapse prevention (2 sessions). Compared with the gold standard CBT for HD,27 this treatment de-emphasizes the use of cognitive therapy techniques and focuses on behavioral interventions (exposures) to discarding and not acquiring. Although the Steketee and Frost manual prescribes the use of problem solving and organizational skills (two to three sessions and as-needed throughout treatment sessions), our intervention dedicated six full sessions (and as-needed throughout treatment) to cognitive rehabilitation of these skill deficits, and included modules on prospective memory and cognitive flexibility that are not present in the standard CBT. All rehabilitation skills were presented in concrete, manualized workbook format, and patients were asked to practice with their own personal examples. Approximately 12.5% to 25% (three to six sessions) of the sessions were home visits due to individual patient needs (e.g., mobility problems). All home visits occurred during the exposure to discarding phase of treatment for the purpose of at-home exposure exercise practice as well as practical assistance for patients with physical impairments. Treatment providers received weekly, 1-hour psychotherapy supervision by the first author of the treatment manual (C.A.).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for all variables and examined for missing values and outliers. Tests of normality of continuous measures were made, and data were examined for homogeneity of variance. No significant variation from the normal distribution was found. Repeated-measures analysis of variance were used to examine change in hoarding severity ratings (SI-R and UHSS) across baseline, midtreatment (end of session 12), and posttreatment. Analysis of variance was used to test changes in the CIR from baseline to postassessment. Anxiety and depression were examined as potential covariates. All tests were two-tailed with a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

The sample included nine women and two men aged 60 to 85 years (mean [standard deviation] (SD): 66 [7] years). Ten participants were white, and one was Hispanic. They were well educated, with a mean of 16.09 (2.21) formal years of education. Two were married, three were divorced, and six had never married. Two participants were taking psychiatric medications for sleep and/or depression. None were taking psychiatric medications prescribed specifically for hoarding symptoms. Participants reported a mean of 3.36 (2.38) medical conditions, most commonly hypertension and high cholesterol. All reported childhood/adolescent onset of hoarding symptoms. Four participants had comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, including major depressive disorder (n = 3), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 2), dysthymia (n = 3), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 2). Hospital Anxiety (mean [SD]: 8.0 [3.87]) and Depression (mean [SD]: 8.89 [3.72]) Scale scores were in the borderline range at baseline.

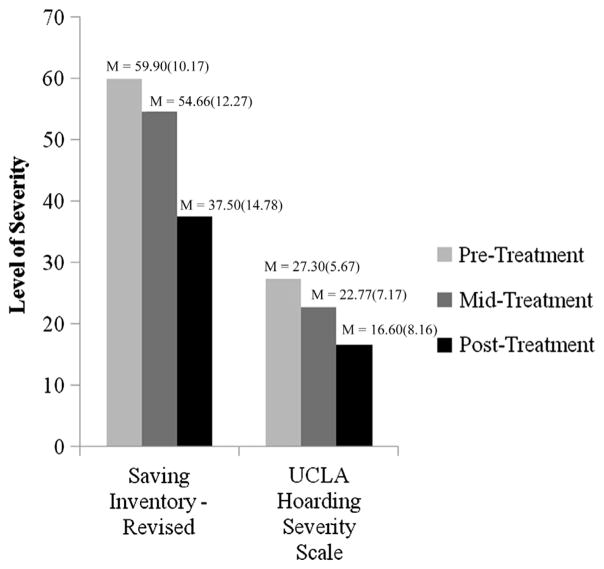

All enrolled participants completed 24 sessions of treatment with no attrition. Average reduction in hoarding severity symptoms was high (SI-R: 8.36%; UHSS: 40.86%; CIR: 25.96%) after treatment (Figure 1). Furthermore, the mean CGI global improvement rating was 1.67 (0.70), indicating “much improved” to “very much improved,” and CGI severity moved from “moderately ill” (4.1) to “mildly ill” (3.0). At posttreatment, eight participants were classified as treatment responders, and three were classified as partial responders. These three partial responders narrowly missed full-response criteria, achieving 23% to 25% reduction on the SI-R and 15% to 33% reduction on the UHSS. Of note, all three partial responders had a comorbid diagnosis of major depressive disorder, with two also meeting the criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Furthermore, they had the highest SI-R ratings of all participants at pretreatment (SI-R: 75, 71, and 67, respectively).

FIGURE 1.

Outcome measures across time points in a sample of 11 older adults receiving cognitive rehabilitation and behavior therapy for hoarding disorder.

Values are given as mean (standard deviation).

Results showed significant main effects of time on hoarding and illness severity measures, with significant changes in SI-R scores (F[1,8] = 167.64; p <0.0001), UHSS scores (F1,8 = 97.60; p <0.0001), CGI severity score (F[1,8] = 18.18; p <0.001), and CIR scores (F[1,6] = 24.20; p = 0.012) from baseline to posttreatment. Effect sizes from pretreatment to posttreatment hoarding severity were large for the SI-R (d = 1.02), UHSS (d = 1.51), and CGI severity scale (d = 0.69) and medium for the CIR (d = 0.41). When depression or anxiety symptoms were used as a covariate, results remained significant.

CONCLUSIONS

This pilot study examined the efficacy of a novel treatment for geriatric HD that combines cognitive rehabilitation with exposure-based treatment, and found that it produced clinically and statistically significant reductions in hoarding severity. These results suggest that a combination of cognitive rehabilitation and exposure to discarding is a feasible, acceptable, and promising treatment for geriatric HD that may be superior to CBT alone. Response rates of hoarding severity scores (38.35%–40.86%) in this study doubled the response rate (18.57%–19.89%) in our previous study of CBT.9 Although the samples were similar with respect to symptom severity and psychiatric comorbidities, the current investigation examined a “young old” group (mean age: 66 years versus 74 years in our previous study). Additional reasons for the results may be due to inclusion of cognitive rehabilitation of executive functioning, concrete behavioral nature of the treatment protocol, and natural tapering of treatment to ensure skills were maintained. Individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders and severe hoarding symptoms may require a more intensive or longer course of treatment. Limitations include the small sample size, lack of a control group, and no long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a Career Development Award (CSRD-068-10S) from the Clinical Science Research and Development Program of the Veterans Health Administration. The contents do not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Diefenbach GJ, DiMauro J, Frost R, et al. Characteristics of hoarding in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:1043–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matrix-Cols D, Frost RO, Pertusa A, et al. Hoarding disorder: a new diagnosis for DSM-V? Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:556–572. doi: 10.1002/da.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fullana MA, Vilagut G, Rojas-Farreras S, et al. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions in the general population: results from an epidemiological study in six European countries. J Affect Disorders. 2010;124:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller A, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, et al. The prevalence of compulsive hoarding and its association with compulsive buying in a German population-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timpano KR, Exner C, Glaesmer H, et al. The epidemiology of the proposed DSM-5 hoarding disorder: exploration of the acquisition specifier, associated features, and distress. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:780–786. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayers CR, Saxena S, Golshan S, Wetherell JL. Age at onset and clinical features of late life compulsive hoarding. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:142–149. doi: 10.1002/gps.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolin DF, Meunier SA, Frost RO, Steketee G. Course of compulsive hoarding and its relationship to life events. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:829–838. doi: 10.1002/da.20684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayers CR, Wetherell JL, Golshan S, Saxena S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for geriatric compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayers CR, Bratiotis C, Saxena S, Wetherell JL. Therapist and patient perspectives on cognitive-behavioral therapy for older adults with hoarding disorder: a collective case study. Aging Ment Health. 2012;61:915–921. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.678480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner K, Steketee G, Nauth L. Treating elders with compulsive hoarding: a pilot program. Cogn Behav Pract. 2010;17:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayers CR, Wetherell JW, Schiehser DM, et al. Executive functioning in older adults with hoarding disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013 Feb 26; doi: 10.1002/gps.3940. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grisham JR, Norberg MM, Williams AD, et al. Categorization and cognitive deficits in compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackin RS, Areán PA, Delucchi KL, Mathews CA. Cognitive functioning in individuals with severe compulsive hoarding behaviors and late life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:314–321. doi: 10.1002/gps.2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMillan SG, Rees CS, Pestell C. An investigation of executive functioning, attention and working memory in compulsive hoarding. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2012:1–16. doi: 10.1017/S1352465812000835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohlman J. Does executive dysfunction affect treatment outcome in late-life mood and anxiety disorders? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005;18:97–108. doi: 10.1177/0891988705276061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, Baxter LR., Jr Paroxetine treatment of compulsive hoarding. J Psychiatry Res. 2007;41:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: saving inventory-revised. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1163–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. A brief interview for assessing compulsive hoarding: the Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N. I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF, Renaud S. Development and validation of the clutter image rating. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2008;30:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guy W. Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewin AA, De Nadai AS, Park J, et al. Refining clinical judgment of treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;185:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Twamley EW, Vella L, Burton CZ, et al. Compensatory cognitive training for psychosis: effects in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1212–1219. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive Hoarding and Acquiring: Therapist Guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]