Abstract

Background:

A growing number of studies have identified cleaners as a group at risk for adverse health effects of the skin and the respiratory tract. Chemical substances present in cleaning products could be responsible for these effects. Currently, only limited information is available about irritant and health hazardous chemical substances found in cleaning products. We hypothesized that chemical substances present in cleaning products are known health hazardous substances that might be involved in adverse health effects of the skin and the respiratory tract.

Methods:

We performed a systematic review of cleaning products used in the Swiss cleaning sector. We surveyed Swiss professional cleaning companies (n = 1476) to identify the most used products (n = 105) for inclusion. Safety data sheets (SDSs) were reviewed and hazardous substances present in cleaning products were tabulated with current European and global harmonized system hazard labels.

Results:

Professional cleaning products are mixtures of substances (arithmetic mean 3.5±2.8), and more than 132 different chemical substances were identified in 105 products. The main groups of chemicals were fragrances, glycol ethers, surfactants, solvents; and to a lesser extent, phosphates, salts, detergents, pH-stabilizers, acids, and bases. Up to 75% of products contained irritant (Xi), 64% harmful (Xn) and 28% corrosive (C) labeled substances. Hazards for eyes (59%) and skin (50%), and hazards by ingestion (60%) were the most reported.

Conclusions:

Cleaning products potentially give rise to simultaneous exposures to different chemical substances. As professional cleaners represent a large workforce, and cleaning products are widely used, it is a major public health issue to better understand these exposures. The list of substances provided in this study contains important information for future occupational exposure assessment studies.

Keywords: Health risk, Irritant, Harmful, Corrosive, Cleaning products, Occupational exposure

Introduction

Professional cleaning is a basic service occupation worldwide, and cleaning products are used daily in different environments, both indoors and outdoors.1,2 In recent years, a growing number of scientific studies have shown an association of cleaning work with respiratory adverse effects including asthma.3–5 In addition, skin diseases such as dermatitis of the hand have also been reported.6–8 One explanation for the observed respiratory adverse health effects among cleaning workers is chemical exposures deriving from cleaning products.2,9–11

Several studies have investigated the relationship between adverse health effects, cleaning activity, and cleaning products.12–19 Several risk factors were identified including exposure to chemical substances via application of cleaning products and other cleaning activities. Researchers have called for objective and more accurate estimates of occupational exposure to cleaning products in order to better understand their adverse effects.12 One major difficulty in this context is the multitude of cleaning products used, and the large number of chemical substances present in these products. Moreover, cleaning products are constantly changing because of ecological, economic, and consumer demands.

Safety data sheets (SDSs) for professional cleaning products are made available to provide workers with health hazard information regarding substances or mixtures. The current EU classification system (Directives 1999/45/EC and 67/548/EEC) defines substances and preparations as dangerous if they are explosive (E), oxidizing (O), extremely or highly flammable (F+, F), very toxic (T+), toxic (T), harmful (Xn), corrosive (C), irritant (Xi), sensitizing (Xn or Xi), carcinogenic (T, Xn), mutagenic (T, Xn), toxic for reproduction (T, Xn), or dangerous for the environment (N). These labels are accompanied by risk phrases (R-phrases), and typical R-phrases used for cleaning products are listed in the Methods section.

We identified frequently used professional cleaning products in Switzerland and through a systematic SDS analysis of these products, hazardous (C, Xn, Xi) substances were identified and listed. We plan to use these results in a future exposure study to better characterize exposures to substances presenting a health hazard among professional cleaning workers.

Methods

Selection of cleaning products

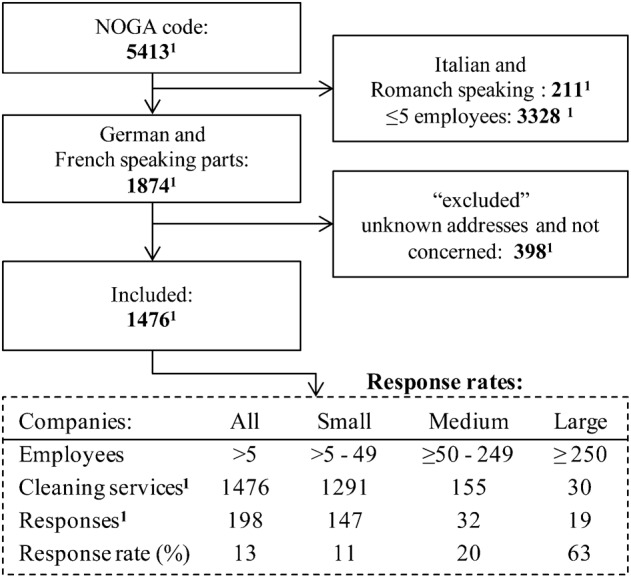

To select a representative group of frequently used cleaning products, we mailed a letter to cleaning companies located in the French- and German-speaking cantons of Switzerland (n = 1476, Fig. 1). The letter mailed to cleaning services was not available in Romansh and Italian languages, thereby excluding cleaning companies in the Romansh and Italian cantons of Switzerland. Cleaning companies were asked to specify cleaning activity, company size, and cleaning products used. Cleaning companies were identified from the Federal Office of Statistics using the code for cleaning companies (‘Nomenclature Générale des Activités économiques’ (NOGA code) (2008)). The NOGA data contained estimates about company size by number of employees. Companies were grouped into small (5–49 employees), medium (50–250 employees), and large (≧250 employees). Technical terms (both French and German) used in the cleaning sector were retrieved from the training manual used for professional cleaners in Switzerland.20 To process the large number of responses, we used the TeleForm software (Cardiff TeleForm, Version 10.5.2, San Diego, USA).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of the decision process for including and excluding (non-French- and non-German-speaking cantons, unknown addresses, or uncommon types of cleaning) cleaning companies in the study. 1 Number of cleaning services selected for the study. The table shows response rates by company size.

The letter included a list of cleaning products (n = 488) from four major companies that manufactured, produced, and/or supplied products in Switzerland. This list of cleaning products by brand names was finalized after discussions with a professional cleaning association, a medium-sized cleaning company, and a training center for professional cleaners. The cleaning companies were asked to mark the cleaning products they used from the provided list, and in the case where the cleaning products they used were not listed, the company was asked to write down these names before mailing the responses back. An Excel spreadsheet was generated from TeleForm and imported to Stata (Stata 12, Stata Corp Lp, Lakeway Drive, USA). Response rates by company size were calculated. Cleaning products marked as being used by at least 10 cleaning companies were included in the systematic SDS analysis.

Safety data sheet analysis

Safety data sheets for cleaning products were obtained from the companies' web sites. If SDSs were not available, products were excluded from the SDS analysis. Selected products were grouped into 10 product categories: floor cleaners (FCs), general purpose cleaners (GPCs), polishing products (PPs), carpet cleaners (CCs), scale removing products (SRPs), bathroom cleaners (BCs), glass cleaners (GCs), disinfection products (DPs), kitchen cleaners (KCs), and other surfaces cleaners (OSCs).

A comprehensive table was created listing all substances mentioned in the SDSs under section 3. Section 3 in the SDS lists all the ingredients in a mixture (chemical name, CAS number, and concentrations) that are classified as health hazards and are present above their cut-off/concentration limits. The frequency of a chemical substance's occurrence in selected products was recorded. Section 3 of SDSs is titled ‘Composition/information on ingredients’ and provides details about hazardous substances in the mixtures. Names, substance identifier (CAS number), concentration or concentration ranges, and classifications according to current danger letters and R-phrases (Directives 1999/45/EC and 67/548/EEC) as well as new hazard classes and statements (Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008) are presented in the table.21–23 This was possible because Switzerland has from 1 December 2010 to 1 June 2017 to replace the current classification system (Directives 1999/45/EC and 67/548/EEC) with the new (Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008), meeting the requirements of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS).24 Therefore, both the current classification and the new GHS labeling were available for this study. The regulations (Directive 67/548/EEC, Directive 1999/45/EC, EC No. 1272/2008) define substance concentration restrictions regarding the listing of substances in this section.21–23 Table 1 includes also the types(s) of cleaning products (FC, GPC, PP, CC, SRP, BC, GC, DP, KC, OSC) where the chemical substances were present. A literature search was performed in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/, 15 October 2013) by searching for ‘substance name’+‘exposure’ and ‘CAS number’+‘exposure’. If available, up to three studies were chosen for each chemical substance that was present in at least two selected cleaning products. Further criteria for the selection of references were ‘publishing date’, ‘health aspects’, ‘dermal and respiratory exposure studies’, ‘occupational exposure studies’, ‘exposure assessment methods’, ‘cleaning’, and ‘cleaning products’.

Table 1. List of substances identified in section 3 of safety data sheets (SDSs) for 105 selected cleaning products, listed in decreasing order of occurrence in products .

| Substance | EU1 | GHS2 | Product3 | |||||||

| Name | CAS | L5 | R6 | C7 | S8 | %9 | N10 | Product type | Reference4 | |

| Isopropyl alcohol | 67-63-0 | F | R11 | Flam.Liq2 | H225 | 1–75 | 16 | FC, GPC, CC, BC, PP | 34–36 | |

| Xi | R20/21/22 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | |||||||

| Xn | R36 | STOTSE3 | H336 | |||||||

| R36/38 | ||||||||||

| R67 | ||||||||||

| Diethylene glycol monoethyl ether | 111-90-0 | Xi | R36 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 0.1–10 | 15 | PP, GPC, FC | 37–39 | |

| EyeDam1 | H318 | |||||||||

| AcuteTox4 | H302 | |||||||||

| AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||||

| Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-tridecyl-omega-hydroxy-, branched | 69011-36-5 | Xn | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–20 | 14 | FC, GPC, DP, CC, SRP, BC | na | |

| R41 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| Dipropylene glycol monomethyl ether | 34590-94-8 | na | na | na | na | 1–20 | 12 | PP, FC, GPC, CC, BC | 40–42 | |

| Citric acid | 77-92-9 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 1–30 | 9 | SRP, BC, FC | 43 | |

| Deceth-4 | 26183-52-8 | Xi | R22 | na | na | 1–15 | 9 | SRP, KC, FC, BC, GPC | na | |

| Xn | R41 | |||||||||

| Ethanol | 64-17-5 | F | R11 | Flam.Liq.2 | H225 | 1–20 | 9 | GPC, PP, FC, BC, OSC | 44–46 | |

| Sulfonic acids, C13–17-sec-alkane, sodium salts | 85711-69-9 | Xi | R38R41 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–15 | 8 | GPC, FC | na | |

| SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | |||||||||

| SkinCorr.1b | H314 | |||||||||

| AcuteTox4 | H302 | |||||||||

| AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||||

| Monoethanolamine | 141-43-5 | C | R20 | SkinCorr.1b | H314 | 1–15 | 8 | FC, DP, GPC | 9, 47–49 | |

| Xn | R21 | STOTSE3 | H335 | |||||||

| R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | ||||||||

| R34 | AcuteTox4 | [H302 H312 H332] | ||||||||

| R37 | ||||||||||

| Benzenesulfonic acid, (1-methylethyl)-, sodium salt (1:1) | 28348-53-0 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 1–10 | 7 | FC, GPC, CC, BC | na | |

| Alcohols, C13–15-branched and linear, butoxylated ethoxylated | 111905-53-4 | Xi | R36/38 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 1–30 | 6 | FC, GPC, CC | na | |

| EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | |||||||||

| Propane | 74-98-6 | F+ | R12 | Flam.Gas1 | H220 | 1–30 | 6 | CC, GPC | 50 | |

| Press.Gas | H280 | |||||||||

| Alcohols, C12–14, ethoxylated | 68439-50-9 | Xn | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–10 | 5 | FC, GPC, SRP | na | |

| R41 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| Benzyl alcohol | 100-51-6 | Xn | R20/22 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 1–20 | 5 | FC, GPC | 51–53 | |

| N | R36 | AcuteTox4 | [H302, H332] | |||||||

| Butane | 106-97-8 | F+ | R12 | Flam.Gas1 | H220 | 15–75 | 5 | CC | 54–56 | |

| Press.Gas | H280 | |||||||||

| Butoxypropanol | 5131-66-8 | Xi | R36/38 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 1–30 | 5 | 57 | ||

| EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | |||||||||

| C12–15 Pareth-11 | 68131-39-5 | Xi | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 0.1–15 | 5 | PP, FC, GPC | 58 | |

| Xn | R41 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| N | R50 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | |||||||

| Diethylene glycol mono-n-butyl ether | 112-34-5 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 5–30 | 5 | FC, SRP, PP | 59–61 | |

| Ethylene glycol | 107-21-1 | Xn | R22 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | 1–20 | 5 | GPC, FC, PP | 62–64 | |

| Ethylene glycol mono-n-butyl ether | 111-76-2 | Xi | R20 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | 1–20 | 5 | GPC, FC, GC | 65–67 | |

| Xn | R21 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | |||||||

| R22 | SkinSens.1 | [H302, H312, H332] | ||||||||

| R36 | AcuteTox4 | |||||||||

| R38 | ||||||||||

| PEG-10 tridecyl ether | 24938-91-8 | Xi | R41 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–15 | 5 | FC, PP, GPC | na | |

| N | R50 | |||||||||

| Phenoxyethanol | 122-99-6 | Xi | R22 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | 1–10 | 5 | PP, FC, GPC | 68 | |

| Xn | R36 | EyeIrrit2 | H319 | |||||||

| Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-isodecyl-omega-hydroxy- | 61827-42-7 | Xi | R22 | na | na | 1–15 | 5 | GPC, PP, OSC | na | |

| Xn | R41 | |||||||||

| Sulfamic acid | 5329-14-6 | Xi | R36/38 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 3–15 | 5 | SRP | na | |

| R52/53 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | ||||||||

| AquaticChronic3 | H412 | |||||||||

| Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-isodecyl-omega-hydroxy- | 107-98-2 | na | R10 | Flam.Liq.3 | H226 | 0.1–<10 | 4 | FC, CC, GPC | na | |

| Phosphoric acid | 7664-38-2 | C | R34 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 5–30 | 4 | GPC, SRP | na | |

| Met.Corr.1 | H290 | |||||||||

| Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-sulfo-omega-hydroxy-, C10–16-alkylethers, sodium salts | 68585-34-2 | Xi | R38 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–15 | 4 | GC, BC, KC, GPC | na | |

| R41 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| Sodium ethasulfate | 126-92-1 | Xi | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–5 | 4 | FC, BC | na | |

| Xn | R38 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | |||||||

| R41 | ||||||||||

| Tri(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate | 78-51-3 | na | na | na | na | 1–5 | 4 | PP | 69 | |

| Alkylalkoholalkoxylat | na | Xi | R36 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 1–10 | 4 | FC, GPC | na | |

| R38 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | ||||||||

| Alcohols, C10–12, ethoxylated propoxylated | 68154-97-2 | N | R51 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | 1–5 | 3 | SRP, FC | na | |

| R53 | ||||||||||

| Alpha-terpineol | 98-55-5 | Xi | R22 | SkinIrit.2 | H315 | 0.01–15 | 3 | GPC, GC | 33, 70, 71 | |

| Xn | R41 | |||||||||

| R38 | ||||||||||

| Ammonium hydroxide | 1336-21-6 | C | R34 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 0.01–1 | 3 | PP, GPC | 72 | |

| N | R50 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| Cyclohexanol, 4-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, 1-acetate | 32210-23-4 | N | R51/53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | 0.1–<5 | 3 | GPC, CC | na | |

| (d)-Limonene | 5989-27-5 | Xi | R10 | Flam.Liq3 | H226 | 0.1–1 | 3 | GC, CC | 73–75 | |

| N | R38 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| R43 | AquaticChronic1 | H410 | ||||||||

| R50/53 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| SkinSens.1 | H317 | |||||||||

| Genapol X 080 | 9043-30-5 | Xi | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 0.1–5 | 3 | PP, GPC | na | |

| Xn | R41 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | |||||||

| R51 | ||||||||||

| R53 | ||||||||||

| Hydrocarbons, terpene processing by-products | 68956-56-9 | Xn | R51/53 | Asp.Tox.1 | H304 | 0.01–1 | 3 | GC, GPC | na | |

| N | R65 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | |||||||

| Fatty acids, coconut oil, potassium salts | 61789-30-8 | Xi | R36/38 | EyeIrrit2 | H319 | 1–5 | 3 | GPC, FC | na | |

| SkinIrrit.2 | H316 | |||||||||

| Naphtha (petroleum), hydrotreated heavy | 64742-48-9 | Xn | R10 | na | na | 3–>30 | 3 | GPC, FC | 76 | |

| R65 | ||||||||||

| R66 | ||||||||||

| Silicic acid, disodium salt, pentahydrate | 10213-79-3 | C | R34 | SkinCorr1B | H314 | 1–15 | 3 | KC, FC | na | |

| Xi | R37 | STOTSE3 | H335 | |||||||

| Sodium hydroxide | 1310-73-2 | C | R35 | SkinCorr.1A | H314 | 0.01–10 | 3 | FC, GC, KC | 77 | |

| Alkylalkoholethoxylat | na | Xi | R22 | na | na | <5–15 | 2 | FC, GPC | na | |

| Xn | R41 | |||||||||

| 1-Propoxy-2-propanol | 1569-01-3 | na | R10 | Flam.Liq3 | H226 | 1–50 | 2 | GC, GPC | 78 | |

| EyeIrrit2 | H319 | |||||||||

| Nerol | 106-25-2 | F | R12 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 0.01–10 | 2 | GC, GPC | 79–81 | |

| Xi | R38 | Flam.Gas1 | H220 | |||||||

| Press.Gas | H280 | |||||||||

| 2-t-Butylcyclohexyl acetate | 88-41-5 | N | R51, R53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | 0.1–1 | 2 | CC, BC | na | |

| Alanine, N,N-bis(carboxymethyl)-, sodium salt (1:3) | 164462-16-2 | na | na | na | na | 1–<5 | 2 | CC, FC | na | |

| Alkanes, C9–12-iso- | 90622-57-4 | Xn | R10 | na | na | 30–75 | 2 | CC, FC | 82 | |

| R53 | ||||||||||

| R65 | ||||||||||

| R66 | ||||||||||

| Coconut acid | 61788-47-4 | Xi | R36/38 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | na | 2 | GPC, FC | 83 | |

| EyeDam1 | H318 | |||||||||

| AcuteTox4 | H302 | |||||||||

| AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||||

| Decyl d-glucoside | 54549-25-6 | Xi | R36 | na | na | 1–5 | 2 | KC, SRP | na | |

| Diphosphoric acid, tetrapotassium salt | 7320-34-5 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H314 | 1–3 | 2 | GPC, FC | na | |

| Heptane | 142-82-5 | F | R11 | Flam.Liq.2 | H225 | 5–20 | 2 | CC | 84, 85 | |

| Xn | R38 | Asp.Tox.1 | H304 | |||||||

| N | R50/53 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| R65 | AquaticChronic1 | H410 | ||||||||

| R67 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| STOTSE3 | H336 | |||||||||

| Isobutane | 75-28-5 | F+ | R12 | Flam.Gas1 | H220 | 3–20 | 2 | CC | 86 | |

| Press.Gas | H281 | |||||||||

| Linalool | 78-70-6 | Xi | R38, R43 | SkinIrrit2, SkinSens.1 | H315, H317 | 0.01–3 | 2 | GC, CC | 87, 88 | |

| Non-ionic tensides | na | Xi | R22 | na | na | 5–30 | 2 | FC | na | |

| Xn | R38 | |||||||||

| N | R50 | |||||||||

| Oxirane, methyl, polymer and oxibane, butyl ether | 9038-95-3 | Xn | R22 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | 3–10 | 2 | FC | na | |

| Polymer dispersion | na | na | na | na | na | na | 2 | PP | na | |

| Quaternary ammonium compounds, benzyl-C12–16-alkyldimethyl, chlorides | 68424-85-1 | C | R21/22 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 3–10 | 2 | GPC | na | |

| N | R34 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| PEG-15 cocoate | 61791-29-5 | Xi | R36 | na | na | 1–5 | 2 | FC, GPC | na | |

| Sodium chloride | 7647-14-5 | C | R34 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 0.01–10 | 2 | GC, SRP | ||

| Sulfuric acid, mono-C12–16-alkyl esters, sodium salts | 73296-89-6 | Xi | R38 | na | na | 5–15 | 2 | CC | na | |

| R37 | Met.Corr.1 | H290 | ||||||||

| STOTSE3 | H335 | |||||||||

| (l)-(−)-Ethyl lactate | 687-47-8 | Xi | R10 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 3–10 | 1 | CC | ||

| R37 | Flam.Liq.3 | H226 | ||||||||

| R41 | STOTSE3 | H335 | ||||||||

| 1,4-Dioxacycloheptadecane-5,17-dione | 105-95-3 | N | R10 | na | na | <5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| R51 | ||||||||||

| R53 | ||||||||||

| 1-Penten-3-one, 1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)- | 7779-30-8 | N | R51/53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| 2-Diethylaminoethanol | 100-37-8 | C | R10 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 1–3 | 1 | GPC | ||

| R20/21/22 | Flam.Liq.3 | H226 | ||||||||

| R34 | AcuteTox4 | [H302, H312, H332] | ||||||||

| 2-Trans-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-ol | 106-24-1 | na | R38 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 0.01–0.1 | 1 | GC | ||

| R41 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| R43 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| 3,7-Dimethyl-6-octen-1-ol | 106-22-9 | Xi | R38 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | <0.01 | 1 | GC | ||

| N | R43 | SkinSens1 | H317 | |||||||

| R51/53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | ||||||||

| 6-Octenenitrile, 3,7-dimethyl- | 51566-62-2 | na | R52/53 | AquaticChronic3 | H412 | 0.01–0.1 | 1 | GC | ||

| Acetyl cedrene | 32388-55-9 | N | R50/53 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| AquaticChronic1 | H410 | |||||||||

| Alcohols, C12–18, ethers with polyethylene glycol mono-Bu ether | 146340-16-1 | N | R50 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 1–5 | 1 | FC | ||

| Xi | R38 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| Acid blue 3 | 3536-49-0 | na | na | na | na | <0.01 | 1 | GC | ||

| Alcohols, C10–16, ethoxylated propoxylated | 69227-22-1 | Xi | R22 | na | na | 5–15 | 1 | FC | ||

| Xn | R41 | |||||||||

| Alcohols, C16–18 and C18–unsatd., ethoxylated | 68920-66-1 | Xn | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 1–3 | 1 | PP | ||

| N | R38 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||

| R41 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| R50 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| Alkyletherphosphatesodiumsalt | na | Xi | R36 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | SRP | ||

| R38 | ||||||||||

| Alpha-d-glucopyranoside, 2-ethylhexyl | 125590-73-0 | Xi | R41 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 3–10 | 1 | BC | ||

| Alpha-isomethylionone | 127-51-5 | Xi | R43 | SkinSens1 | H317 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| R52/53 | AquaticChronic3 | H412 | ||||||||

| Alpha-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)benzenepropanal | 103-95-7 | Xn | R38 | Repr.2 | H361 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| N | R43 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | |||||||

| R51/53 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| R62 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | ||||||||

| Amides, coconut oil, N-(2-((sulfosuccinyl)oxy)ethyl), sodium salts | 68784-08-7 | Xi | R41 | na | na | na | 1 | CC | ||

| Amyl salicylate | 2050-08-0 | N | R51/53 | na | na | <5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| Anethole, trans | 4180-23-8 | N | R51/53 | na | na | <5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| Aromatic naphtha, type I | 64742-95-6 | Xi | R10 | na | na | 0.1–1 | 1 | FC | ||

| Xn | R37 | |||||||||

| N | R53 | |||||||||

| R65 | ||||||||||

| R66 | ||||||||||

| R67 | ||||||||||

| R51 | ||||||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | Xn | R22 | na | na | na | 1 | GPC | ||

| Benzenesulfonic acid, 4-C10–13-sec-alkyl derivs. | 85536-14-7 | C | R22 | SkinCorr.1C | H314 | 3–10 | 1 | SRP | ||

| R34 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| Benzenesulfonic acid, mono-C10–13-alkyl derivs., compds. With ethanolamine | 85480-55-3 | Xn | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 3–10 | 1 | FC | ||

| R38 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| R41 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| Benzenesulfonic acid, mono-C10–13-alkyl derivs., sodium salts | 90194-45-9 | Xn | R22 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 3–10 | 1 | GPC | ||

| R38 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| R41 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| Benzyl acetate | 140-11-4 | Xi | R36/37/38 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | oct.20 | 1 | CC | ||

| EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | |||||||||

| STOTSE3 | H335 | |||||||||

| Benzyl benzoate | 120-51-4 | Xn | R22 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | 1–3 | 1 | CC | ||

| N | R51/53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | |||||||

| Benzyl salicylate | 118-58-1 | Xi | R43 | SkinSens1 | H317 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| N | R51/53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | |||||||

| Beta-pinene | 127-91-3 | Xn | R65 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | na | 1 | PGPC | ||

| N | R50 | EyeDam1 | H318 | |||||||

| R53 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | ||||||||

| AquaticAcute1 | H400 | |||||||||

| Butanedioic acid, sulfo-, 1-ester with N-(2-hydroxyethyl)dodecanamide, disodium salt | 25882-44-4 | Xi | R36/38 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 3–10 | 1 | CC | ||

| EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | |||||||||

| C11–15 Pareth-20 | 68131-40-8 | Xi | R22 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| Xn | R41 | |||||||||

| Camphene | 79-92-5 | F | R11 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | na | 1 | FC | ||

| Xi | R36 | EyeDam1 | H318 | |||||||

| N | R50 | AcuteTox4 | H302 | |||||||

| R53 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | ||||||||

| Citral | 5392-40-5 | Xi | R38 | SkinIrrit2 | H315 | 0.01–0.1 | 1 | GC | ||

| R43 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| Coumarin | 91-64-5 | Xn | R22 | AcuteTox3 | H301 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| R43 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| d-Glucopyranose, oligomeric, decyl octyl glycosides | 68515-73-1 | Xi | R41 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | BC | ||

| Diethylene glycol monomethyl ether | 111-77-3 | na | R63 | na | na | na | 1 | PP | ||

| Dimethyl ether | 115-10-6 | F+ | R12 | na | na | 50–75 | 1 | CC | ||

| Disodium phosphate | 7558-79-4 | na | na | na | na | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| Ethylene glycol monomontanate | 73138-45-1 | na | na | na | na | 3–10 | 1 | PP | ||

| Eugenol | 97-53-0 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| R43 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| Fatty acids, coco, 2-(2-butoxyethoxy)ethyl esters | 91031-83-3 | Xi | R36 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | FC | ||

| Fatty acid amides | na | Xi | R38 | na | na | <5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| R41 | ||||||||||

| Galaxolide | 1222-05-5 | N | R50/53 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| AquaticChronic1 | H410 | |||||||||

| Hydroxyacetic acid | 79-14-1 | C | R34 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | SRP | ||

| Isoeugenol | 97-54-1 | Xn | R21/22 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| R36/38 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | ||||||||

| R43 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| AcuteTox4 | [H302, H312] | |||||||||

| Laurylamine dipropylenediamine | 2372-82-9 | C | R22 | AcuteTox.3 | H301 | 0.1–1 | 1 | DP | ||

| N | R35 | SkinCorr.1A | H314 | |||||||

| R48/22 | STOTRE2 | H373 | ||||||||

| R50 | AquaticAcute1 | H400 | ||||||||

| Lilial | 80-54-6 | Xi | R22 | Repr.2 | H361 | <0.01 | 1 | GC | ||

| Xn | R38 | Acute Tox4 | H302 | |||||||

| N | R43 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | |||||||

| R62 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| R51/53 | AquaticChronic2 | H411 | ||||||||

| Lyral | 31906-04-4 | Xi | R43 | SkinSens1 | H317 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| R52/53 | AquaticChronic3 | H412 | ||||||||

| Methanesulfonic acid | 75-75-2 | C | R34 | SkinCorr.1B | H314 | 3–10 | 1 | BC | ||

| Mineral oil | 8012-95-1 | Xn | R65 | 5–15 | 1 | FC | ||||

| Naphtha (petroleum), heavy alkylate | 64741-65-7 | Xn | R10 | AcuteTox.3 | H331 | >75 | 1 | PP | ||

| R53 | Asp.Tox.1 | H304 | ||||||||

| R65 | Flam.Liq.3 | H226 | ||||||||

| R66 | AquaticChronic4 | [H413, EUH006] | ||||||||

| Natriumlaurylethoxylsulfate | na | Xi | R38 | na | na | <5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| R41 | ||||||||||

| n-Octyl-polyoxyethylene | 27252-75-1 | Xi | R41 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | FC | ||

| Pentapotassium triphosphate | 13845-36-8 | Xi | R36/38 | na | na | 5–15 | 1 | GPC | ||

| Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-propyl- | 2785-87-7 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| R43 | SkinSens.1 | H317 | ||||||||

| Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-sulfo-omega-hydroxy-, C12–14-alkyl ethers, sodium salts | 68891-38-5 | Xi | R38 | EyeDam1 | H318 | <10 | 1 | FC | ||

| R41 | SinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyl), alpha-(2-propylheptyl)-omega-hydroxy- | 160875-66-1 | Xi | R41 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 03–10 | 1 | FC | ||

| Polyoxyl 20 cetostearyl ether | 68439-49-6 | N | R41 | na | na | 0.1–1 | 1 | PP | ||

| R50 | ||||||||||

| Potassium hydroxide | 1310-58-3 | C | R22 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | FC | ||

| Xn | R35 | |||||||||

| Silicon dioxide | 7631-86-9 | na | na | na | na | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| Sodium 2-butoxyethyl sulfate | 67656-24-0 | Xi | R36/38 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | FC | ||

| Sodium benzoate | 532-32-1 | na | na | na | na | 0.1–1 | 1 | CC | ||

| Sodium carbonate | 497-19-8 | Xi | R36 | EyeIrrit.2 | H319 | 1–3 | 1 | DP | ||

| Sodium sulfate | 7757-82-6 | na | na | na | na | 0.01–0.1 | 1 | GC | ||

| Solvent naphtha (petroleum), heavy arom. | 64742-94-5 | Xn | R51/53 | Asp.Tox.1 | H304 | 0.1–1 | 1 | PP | ||

| N | R65 | STOTSE3 | H336 | |||||||

| R66 | AquaticChronic2 | [H411, EUH006] | ||||||||

| Solvent naphtha (petroleum), medium aliph. | 64742-88-7 | Xn | R10 | na | na | 25–50 | 1 | OSC | ||

| R56 | ||||||||||

| Sulfuric acid, mono-C10–16-alkyl esters, sodium salts | 68585-47-7 | Xi | R38 | EyeDam1 | H318 | 3–10 | 1 | CC | ||

| R41 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | ||||||||

| Sulfuric acid, mono-C12–14-alkyl esters, sodium salts | 85586-07-8 | Xi | R38 | na | na | na | 1 | CC | ||

| R41 | ||||||||||

| Sulfuric acid, mono-C12–16-alkyl esters, sodium salts | 73296-89-6 | Xi | R38 | na | na | 5–15 | 2 | CC | ||

| R41 | ||||||||||

| Sodium C14–16 olefin sulfonate | 68439-57-6 | Xi | R38 | SkinIrrit.2 | H315 | 1–5 | 1 | CC | ||

| R41 | EyeDam1 | H318 | ||||||||

| Terpinolene | 586-62-9 | Xn | R10 | na | na | <5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| N | R51/53 | |||||||||

| R65 | ||||||||||

| Triethanolamine | 102-71-6 | Xi | R36/38 | na | na | 1–5 | 1 | GPC | ||

| Waxmixture | na | na | na | na | na | na | 1 | PP | ||

NA: not available; FC: floor cleaner; GPC: general purpose cleaner; PP: polishing product; CC: carpet cleaner; SRP: scale removing product; BC: bathroom cleaner; GC: glass cleaner; DP: disinfection product; KC: kitchen cleaner; OSC: other surfaces cleaner.

1 Directives 1999/45/EC and 67/548/EEC.

2 Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008.

3 Information about amount and frequency in selection of professional cleaning product.

4 Studies about substances listed in Table 1, when substances where present in at least two cleaning products.

5 Danger letter.

6 Risk-phrase.

7 Hazard class.

8 Hazard statement.

9 Amount of substance in selected professional cleaning products.

10 Number of selected professional cleaning products that contain the listed chemical substance.

Fragrances sometimes do not meet the criteria to be listed in section 3 ‘Composition/information on ingredients’ of the SDSs (e.g. low concentration). However fragrances, preservatives, and others are mentioned in section 15 ‘Regulatory Information’ if they are subjected to other regulations such as substances depleting the ozone layer ((EC) No. 2037/2000, persistent organic pollutants (EC) No. 850/2004, and export/import of dangerous substances (EC) No. 689/2008).25–27 Names of fragrances, preservatives, and other chemical substances listed under section 15 of SDSs are reported in the Results section.

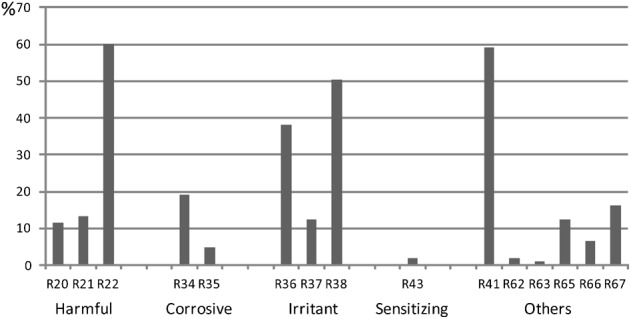

Cleaning products containing at least one substance listed with corrosive, irritant, and harmful symbols under the current EU classification system were counted and expressed in percentage for each of the 10 product categories. Similar results were presented for the R-phrases. R-phrases relevant in this study are harmful by inhalation (R20), are harmful in contact with skin (R21), are harmful if swallowed (R22), causes burns (R34), causes severe burns (R35), is irritating to eyes (R36), is irritating to respiratory system (R37), is irritating to skin (R38), has risk of serious damage to eyes (R41), may cause sensitization by skin contact (R43), has danger of serious damage to health by prolonged exposure (R48), has possible risk of impaired fertility (R62), has possible risk of harm to the unborn child (R63), is harmful: may cause lung damage if swallowed (R65), repeated exposure may cause skin dryness or cracking (R66), and vapors may cause drowsiness and dizziness (R67).The fractions of cleaning products, with at least one substance listed with the R-phrases R20, R21, R22, R34, R35, R36, R37, R38, R41, R43, R48, R62, R63, R65, R66, and R67, were expressed in percentage.

Results

The response rate to the letter sent to cleaning companies was the highest (50%) for large companies (≧250 employees), and lower for medium (24%) and small (11%) companies (Fig. 1). Based on company responses, respondent companies employed >40 000 employees. A total of 116 products were selected for SDS analysis and 11 products were excluded because of missing SDSs. In the 105 remaining selected products, 132 different chemical substances were listed in the SDSs reviewed. In average, one cleaning product contained 3.5 (±2.8) chemical substances listed in section 3 of the SDSs. The composition of the cleaning products varied depending on their intended use. The substances we identified are listed in Table 1. Although the type of glycol ethers varied greatly across cleaning products, they were often (20% of the products) present in both small and large amounts (0.1–50% in the products). Most glycol ethers were found in PPs (48%), SRPs (42%), GPCs (37%), and FCs (36%); some (20%) were found in DPs and KCs, and few (10–11%) were found in GCs, BCs, and CCs. The choice of surfactants was diverse but were present in 19% of the products and their concentration ranges varied greatly (0.1–30% in the products). We particularly focused on ethanolamines, known for their sensitizing properties.28 Three ethanolamines were identified: monoethanolamine, triethanolamine, and 2-diethylaminoethanol. The most frequently used was monoethanolamine, which was present in eight products (n = 8): five FCs, two GPCs, and one KC. In all, 16% of the products contained organic solvents and the concentration ranges varied enormously (0.1–75%) making up 75% of one of the products (PP). Other typical ingredients, although in lower concentrations, accounted for 18% of our substance list (Table 1): phosphates, salts, detergents, pH-stabilizers, acids, and bases. Quaternary ammonium compounds or ‘quats’, a substance class known for sensitizing and allergic responses among cleaners, were found in two products in 3–10% concentrations.2,29

Fragrances were commonly (27% of identified substances) found in low concentrations (0.01–5%), except when they also acted as a solvent (30%). Interestingly, up to 91% of the selected cleaning products contained at least one substance that was subject to other regulations and are listed under section 15 of SDSs. In total, 26 substances were found under section 15 of the SDS (Table 2).

Table 2. Fraction of selected cleaning products (%) that contain the listed chemical substance.

| Substance name | P (%) |

| Linalool | 20 |

| Butylphenyl methylpropional | 16 |

| Benzisothiazolinone | 16 |

| Hexyl cinnamal | 15 |

| Limonene | 14 |

| Methylisothiazolione | 12 |

| Aliphatic carbohydrates | 9–10 |

| Amyl cinnamal | 9–10 |

| Benzyl salicylate | 9–10 |

| Citronellol | 9–10 |

| Formaldehyde deposit alpha mixture with 5-chloro-2-methyl-2H-isothiazol-3-one 2-methyl-2H-isothiazol-3-one | 9–10 |

| Hydroxycitronellol | 9–10 |

| Hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxyaldehyde | 9–10 |

| Isoeugenol | 9–10 |

| Sodium hydroxymethylglycinate | 9–10 |

| Alpha-isomethyl ionone | <7 |

| Benzyl alcohol | <7 |

| Benzyl benzoate | <7 |

| Cinnamal, citral | <7 |

| Coumarin | <7 |

| Eugenol | <7 |

| Geraniol | <7 |

| Glutaral | <7 |

| Octylisothiazolinone | <7 |

| Phenoxyethanol | <7 |

In all, 11 substances listed in section 3 of SDSs were neither classified with danger symbol letters and R-phrases nor with hazard classes and categories. The remaining 117 substances were classified with danger symbol letters and R-phrases as well as with hazard classes and categories. Of these, 82 substances were listed in addition to hazard classifications and statements (GHS). In all, 4 substances were listed in SDSs of more than 10 products, 17 substances in SDSs of 5–10 products, 38 in SDSs of 2–4 products, and 69 were mentioned only once in the SDSs of the 105 selected cleaning products.

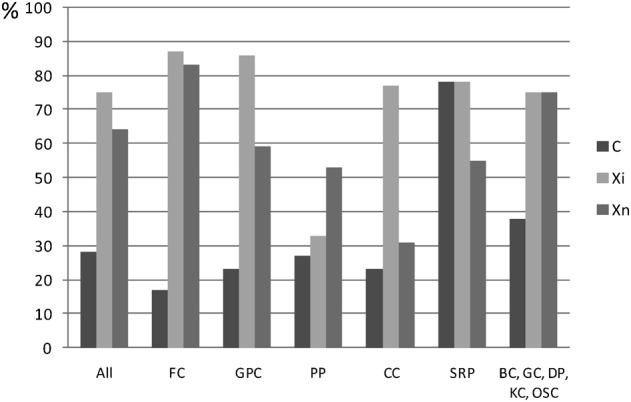

By product categories, usually less than 40% of cleaning products were labeled corrosive (C) in section 3 of SDSs, with exception SRPs (78%, Fig. 2). In most product categories, more than 70% of the products were labeled irritant (Xi), except for PPs (33%). More than 50% of the products were labeled harmful (Xn), except for product category CCs (31%).

Figure 2.

Percentages of products by product categories containing at least one substance labeled as corrosive (C), irritant (Xi), and harmful (Xn) in section 3 of SDSs. Floor cleaner (FC), general purpose cleaner (GPC), polishing product (PP), carpet cleaner (CC), scale removing product (SRP), bathroom cleaner (BC), glass cleaner (GC), disinfection product (DP), kitchen cleaner (KC), and other surfaces cleaner (OSC).

A total of 15 R-phrases regarding human health were identified (Fig. 3): corrosive (R34, R35), irritant (R36, R37, R38), harmful (R20, R21, R22), sensitizing (R43), and others (R41, R62, R63, R65, R66, R67). Figure 3 shows the percentages of products (all categories) that have been labeled with these R-phrases in section 3 of SDSs.

Figure 3.

Percentages of cleaning products that have been labeled with corrosive (R34, R35), irritant (R36, R37, R38), harmful (R20, R21, R22), sensitizing (R43), and other (R41, R62, R63, R65, R66, R67) R-phrases in section 3 of safety data sheets (SDSs).

Discussion

Frequently used professional cleaning products contain a multitude of chemical substances with known health effects. Cleaners may therefore be exposed to mixtures of health hazardous substances during their cleaning activity.

It is important to note that SDSs do not list all chemical substances present in a product, as regulations define substances and concentrations that must be listed.21,23 Depending on the characteristics of the substances (e.g. persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity), the concentration levels requiring listing are 1 or 0.1%.30 Sensitizers were listed as a cleaning product ingredient under section 15 in the SDSs only if required by other regulations.25–27 Interestingly, several substances found under section 15 of SDSs have been associated with sensitizing mechanisms and/or allergic reactions.

In our study, we selected frequently used cleaning products known from cleaning companies with five or more employees. The cleaning products included the four most popular brands that, according to a professional association for cleaning companies in Switzerland, account for >50% of the Swiss professional cleaning products market.

As mentioned above, we estimated that our results include products used by about 50% of the Swiss cleaning workforce. This is because the large cleaning companies reported to have high numbers of employees (more than several thousand). Most cleaning products identified in this study were sold by global companies that sell and distribute their products worldwide. The results of this study may hold true for other industrialized countries similar to Switzerland, although the cleaning product might be given a different brand name.

Not only is there a great diversity of chemical substances within cleaning products but also numerous companies offer hundreds of different cleaning products, which makes the task of assessing chemical substances used in professional cleaning products complicated. Indeed, responses showed cleaning companies using products from 36 different product companies, and some reported that they produced their own products. Thus when investigating exposures among professional cleaners, a SDS review is a requirement. We believe our results provide important information regarding type of cleaning products used in this industry, and common chemical substance classes found in these products and their health hazards. This knowledge should help in monitoring professional cleaners and their exposures to cleaning products and substances with known health effects. In addition, not only cleaning workers or those who are cleaning are at risk of exposure but also persons in rooms that were recently cleaned can potentially be exposed.31–33

The main challenges in conducting an occupational exposure assessment for professional cleaners are the great number of cleaning products available and the large number of substances in these products. For further investigation, we recommend to focus on the 21 substances found in ≧5 products (Table 1). Especially of interest are the recognized sensitizers monoethanolamine and glycol ethers, frequently found in cleaning products. Substances found in professional cleaning products may likely also be ingredients in cleaning products sold to the general public; however, we did not survey these products.28

Conclusion

This work contributes to the efforts to better understand possible exposures to chemicals during the use of professional cleaning products. We found that hazardous substances in cleaning products are in particular fragrances, glycol ethers, surfactants, solvents, and to a lesser extent phosphates, salts, detergents, pH-stabilizers, acids, and bases. Cleaning workers who are handling these products are therefore a group at risk for several occupational exposures. Section 15 in the SDS should be consulted, as several substances involved in sensitizing mechanisms and/or allergic reactions were also listed here. Especially glycol ethers and ethanolamines are frequently used in cleaning products, and could therefore be involved in the development of adverse health effects like irritant or sensitizer-induced asthma, which has been found to be elevated among professional cleaners. Concerning asthma, the presence of different aldehydes as fragrances is also of special interest. Besides some sensitizers like ethanolamines, mainly irritants were found, suggesting that pathologies of the skin and the respiratory tract may also occur without mechanisms of sensitization. A simultaneous exposure to several hazardous chemical substances could potentially be involved in these pathologies. As professional cleaners represent a large workforce, and cleaning products are widely used, including in private cleaning, it is of great environmental and public health importance to better understand the exposures that may be caused by the use of cleaning products. Our list of substances provides important information about which chemicals and hazards are relevant for further investigations in this field, and we plan to use these results for field exposure studies.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Federal Office for Public Health of Switzerland (Office fédérale de la santé publique [OFSP], Bundesamt für Gesundheit [BAG]) for funding this study.

References

- 1.Zock JP. World at work: cleaners. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(8):581–4. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.015032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quirce S, Barranco P. Cleaning agents and asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2010;20(7):542–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arif AA, Delclos GL, Whitehead LW, Tortolero SR, Lee ES. Occupational exposures associated with work-related asthma and work-related wheezing among U.S. workers. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44(4):368–76. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zock JP, Vizcaya D, Le Moual N. Update on asthma and cleaners. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(2):114–20. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833733fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaakkola JJ, Jaakkola MS. Professional cleaning and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(2):85–90. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000216849.64828.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynde CB, Obadia M, Liss GM, Ribeiro M, Holness DL, Tarlo SM. Cutaneous and respiratory symptoms among professional cleaners. Occup Med. 2009;59(4):249–54. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diepgen TL, Coenraads PJ. The epidemiology of occupational contact dermatitis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72(8):496–506. doi: 10.1007/s004200050407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gawkrodger DJ, Lloyd MH, Hunter JA. Occupational skin disease in hospital cleaning and kitchen workers. Contact Dermatitis. 1986;15(3):132–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1986.tb01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bello A, Quinn M, Perry M, Milton D. Characterization of occupational exposures to cleaning products used for common cleaning tasks-a pilot study of hospital cleaners. Environ Health. 2009;8(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medina-Ramón M, Zock JP, Kogevinas M, Sunyer J, Torralba Y, Borrell A, et al. Asthma, chronic bronchitis, and exposure to irritant agents in occupational domestic cleaning: a nested case-control study. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(9):598–606. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.017640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Moual N, Kennedy SM, Kauffmann F. Occupational exposures and asthma in 14,000 adults from the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(11):1108–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumas O, Donnay C, Heederik DJ, Héry M, Choudat D, Kauffmann F, et al. Occupational exposure to cleaning products and asthma in hospital workers. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(12):883–9. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zock JP, Plana E, Jarvis D, Anto JM, Kromhout H, Kennedy SM, et al. The use of household cleaning sprays and adult asthma: an international longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(8):735–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1793OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zock JP, Plana E, Anto JM, Benke G, Blanc PD, Carosso A, et al. Domestic use of hypochlorite bleach, atopic sensitization, and respiratory symptoms in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(4):731–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makela R, Kauppi P, Suuronen K, Tuppurainen M, Hannu T. Occupational asthma in professional cleaning work: a clinical study. Occup Med (Lond). 2011;61(2):121–6. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vizcaya D, Mirabelli MC, Antó J-M, Orriols R, Burgos F, Arjona L, et al. A workforce-based study of occupational exposures and asthma symptoms in cleaning workers. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(12):914–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.063271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wieslander G, Norbäck D. A field study on clinical signs and symptoms in cleaners at floor polish removal and application in a Swedish hospital. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83(5):585–91. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arif AA, Delclos GL. Association between cleaning-related chemicals and work-related asthma and asthma symptoms among healthcare professionals. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(1):35–40. doi: 10.1136/oem.2011.064865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zock JP, Kogevinas M, Sunyer J, Almar E, Muniozguren N, Payo F, et al. Asthma risk, cleaning activities and use of specific cleaning products among Spanish indoor cleaners. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2001;27(1):76–81. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Allpura. Manuel de formation ‘La technique du nettoyage’, edn. Zurich, Verlag USTER-Info GmbH; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Parliament C. Directive 1999/45/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 1999 concerning the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the classification, packaging and labelling of dangerous preparations. 1999. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 22.European Parliament C. Council Directive 67/548/EEC of 27 June 1967 on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to the classification, packaging and labelling of dangerous substances. 1967. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Parliament C. Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 (Text with EEA relevance). 2008. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Parliament C. Commission Regulation (EU) No 453/2010 of 20 May 2010 amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) (Text with EEA relevance). 2010. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Parliament C. Regulation (EC) No 2037/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 June 2000 on substances that deplete the ozone layer. 2000. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Parliament C. Regulation (EC) No 850/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on persistent organic pollutants and amending Directive 79/117/EEC. 2004. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 27.European Parliament C. Regulation (EC) No 689/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 concerning the export and import of dangerous chemicals. 2008. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lessmann H, Uter W, Schnuch A, Geier J. Skin sensitizing properties of the ethanolamines mono-, di-, and triethanolamine. Data analysis of a multicentre surveillance network (IVDK) and review of the literature. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60(5):243–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purohit A, Kopferschmitt-Kubler MC, Moreau C, Popin E, Blaumeiser M, Pauli G. Quaternary ammonium compounds and occupational asthma. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73(6):423–7. doi: 10.1007/s004200000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Parliament C. Commission Regulation (EU) No 451/2010 of 25 May 2010 establishing the standard import values for determining the entry price of certain fruit and vegetables. 2010. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bello A, Quinn M, Perry M, Milton D. Quantitative assessment of airborne exposures generated during common cleaning tasks: a pilot study. Environ Health. 2010;9(1):76. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazaroff WW, Weschler CJ. Cleaning products and air fresheners: exposure to primary and secondary air pollutants. Atmos Environ. 2004;38(18):2841–65. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer BC, Destaillats H, Hodgson AT, Nazaroff WW. Cleaning products and air fresheners: emissions and resulting concentrations of glycol ethers and terpenoids. Indoor Air. 2006;16(3):179–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2005.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capron A, Destree J, Jacobs P, Wallemacq P. Permeability of gloves to selected chemotherapeutic agents after treatment with alcohol or isopropyl alcohol. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(19):1665–70. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desy O, Carignan D, Caruso M, de Campos-Lima PO. Immunosuppressive effect of isopropanol: down-regulation of cytokine production results from the alteration of discrete transcriptional pathways in activated lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181(4):2348–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carignan D, Desy O, de Campos-Lima PO. The dysregulation of the monocyte/macrophage effector function induced by isopropanol is mediated by the defective activation of distinct members of the AP-1 family of transcription factors. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125(1):144–56. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy CJ, Coombs DW, Lewis DJ, Klimisch HJ. Twenty-eight-day repeated-dose inhalation exposure of rats to diethylene glycol monoethyl ether. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1997;38(2):143–7. doi: 10.1006/faat.1997.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams J, Reel JR, George JD, Lamb JC. Reproductive effects of diethylene glycol and diethylene glycol monoethyl ether in Swiss CD-1 mice assessed by a continuous breeding protocol. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1990;14(3):622–35. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(90)90266-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hobson DW, D'Addario AP, Bruner RH, Uddin DE. A subchronic dermal exposure study of diethylene glycol monomethyl ether and ethylene glycol monomethyl ether in the male guinea pig. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1986;6(2):339–48. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(86)90249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koontz M, Price P, Hamilton J, Daggett D, Sielken R, Bretzlaff R, et al. Modeling aggregate exposures to glycol ethers from use of commercial floor products. Int J Toxicol. 2006;25(2):95–107. doi: 10.1080/10915810600605724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson V, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Klaassen CD, Marks JG, Jr, Shank RC, et al. Final report on the safety assessment of PPG-2 methyl ether, PPG-3 methyl ether, and PPG-2 methyl ether acetate. Int J Toxicol. 2009;28(6 Suppl):162S–74S. doi: 10.1177/1091581809350933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shih HC, Tsai SW, Kuo CH. Time-weighted average sampling of airborne propylene glycol ethers by a solid-phase microextraction device. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2012;9(7):427–36. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.685851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Franova S, Joskova M, Sadlonova V, Pavelcikova D, Mesarosova L, Novakova E, et al. Experimental model of allergic asthma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;756:49–55. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4549-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hautemaniere A, Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Cunat L, Hartemann P. Assessment of transpulmonary absorption of ethanol from alcohol-based hand rub. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(3):e15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hautemaniere A, Cunat L, Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Hajjard F, Gerardin F, Morele Y, et al. Assessment of exposure to ethanol vapors released during use of Alcohol-Based Hand Rubs by healthcare workers. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phalen RN, Wong WK. Chemical resistance of disposable nitrile gloves exposed to simulated movement. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2012;9(11):630–9. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.723584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeuchi A, Kitade T, Jukurogi A, Hendricks W, Kaifuku Y, Shibayama K, et al. Determination method for mono- and diethanolamine in workplace air by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Occup Health. 2012;54(4):340–3. doi: 10.1539/joh.12-0064-br. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerster FM, Hopf NB, Huynh CK, Plateel G, Charrière N, Vernez D. A simple gas chromatography method for the analysis of monoethanolamine in air. J Sep Sci. 2012;35(17):2249–55. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201200196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arias Irigoyen J, Garrido Borrero P. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from monoethanolamine in a metal worker. Allergol Immunopathol. 2011;39(3):187–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sahmel J, Devlin K, Burns A, Ferracini T, Ground M, Paustenbach D. An analysis of workplace exposures to benzene over four decades at a petrochemical processing and manufacturing facility (1962–1999). J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2013;76(12):723–46. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2013.821393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawai T, Yamauchi T, Miyama Y, Sakurai H, Ukai H, Takada S, et al. Benzyl alcohol as a marker of occupational exposure to toluene. Ind Health. 2007;45(1):143–50. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.[Indoor air guide values for benzyl alcohol] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53(9):984–7. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1123-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnuch A, Mildau G, Kratz EM, Uter W. Risk of sensitization to preservatives estimated on the basis of patch test data and exposure, according to a sample of 3541 leave-on products. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65(3):167–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sirdah MM, Al Laham NA, El Madhoun RA. Possible health effects of liquefied petroleum gas on workers at filling and distribution stations of Gaza governorates. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(3):289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bessonneau V, Mosqueron L, Berrube A, Mukensturm G, Buffet-Bataillon S, Gangneux JP, et al. VOC contamination in hospital, from stationary sampling of a large panel of compounds, in view of healthcare workers and patients exposure assessment. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jezewska A, Szewczynska M. [Chemical hazards in the workplace environment of painting restorer]. Med Pr. 2012;63(5):547–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Formaldehyde, 2-butoxyethanol and 1-tert-butoxypropan-2-ol. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2006;88:1–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong DC, Toy RJ, Dorn PB. A stream mesocosm study on the ecological effects of a C12-15 linear alcohol ethoxylate surfactant. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2004;58(2):173–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laitinen J, Pulkkinen J. Biomonitoring of 2-(2-alkoxyethoxy)ethanols by analysing urinary 2-(2-alkoxyethoxy)acetic acids. Toxicol Lett. 2005;156(1):117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gijsbers JH, Tielemans E, Brouwer DH, van Hemmen JJ. Dermal exposure during filling, loading and brushing with products containing 2-(2-butoxyethoxy)ethanol. Ann Occup Hyg. 2004;48(3):219–27. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/meh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibson WB, Keller PR, Foltz DJ, Harvey GJ. Diethylene glycol mono butyl ether concentrations in room air from application of cleaner formulations to hard surfaces. J Exposure Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):369–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kruse JA. Methanol and ethylene glycol intoxication. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28(4):661–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saghir SA, Bartels MJ, Snellings WM. Dermal penetration of ethylene glycol through human skin in vitro. Int J Toxicol. 2010;29(3):268–76. doi: 10.1177/1091581810366604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Upadhyay S, Carstens J, Klein D, Faller TH, Halbach S, Kirchinger W, et al. Inhalation and epidermal exposure of volunteers to ethylene glycol: kinetics of absorption, urinary excretion, and metabolism to glycolate and oxalate. Toxicol Lett. 2008;178(2):131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hung PC, Cheng SF, Liou SH, Tsai SW. Biological monitoring of low-level 2-butoxyethanol exposure in decal transfer workers in bicycle manufacturing factories. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(10):777–82. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.061184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boatman R, Corley R, Green T, Klaunig J, Udden M. Review of studies concerning the tumorigenicity of 2-butoxyethanol in B6C3F1 mice and its relevance for human risk assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health, Part B. 2004;7(5):385–98. doi: 10.1080/10937400490498084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones K, Cocker J. A human exposure study to investigate biological monitoring methods for 2-butoxyethanol. Biomarkers. 2003;8(5):360–70. doi: 10.1080/13547500310001600941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Warshaw EM, Raju SI, Fowler JF, Jr, Maibach HI, Belsito DV, Zug KA, et al. Positive patch test reactions in older individuals: retrospective analysis from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1994–2008. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(2):229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saitoh M, Umemura T, Kawasaki Y, Momma J, Matsushima Y, Matsumoto M, et al. [Subchronic toxicity study of tributoxyethyl phosphate in Wistar rats]. Eisei Shikenjo Hokoku. 1994;112:27–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Forester CD, Wells JR. Hydroxyl radical yields from reactions of terpene mixtures with ozone. Indoor Air. 2011;21(5):400–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2011.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ham JE, Wells JR. Surface chemistry of a pine-oil cleaner and other terpene mixtures with ozone on vinyl flooring tiles. Chemosphere. 2011;83(3):327–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kollef MH. Chronic ammonium hydroxide exposure. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(1):118. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-1-118_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim YW, Kim MJ, Chung BY, Bang du Y, Lim SK, Choi SM, et al. Safety evaluation and risk assessment of d-Limonene. J Toxicol Environ Health, Part B. 2013;16(1):17–38. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2013.769418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krol S, Namiesnik J, Zabiegala B. Alpha-Pinene, 3-carene and d-limonene in indoor air of Polish apartments: the impact on air quality and human exposure. Sci Total Environ. 2013;468–469C:985–95. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Api AM, Ritacco G, Hawkins DR. The fate of dermally applied [14C]d-limonene in rats and humans. Int J Toxicol. 2013;32(2):130–5. doi: 10.1177/1091581813479979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sagunski H, Mangelsdorf I. States' Departments of H and Federal Environmental Protection A. [Reference values for indoor air: dearomatized hydrocarbon solvents (C(9)-C(14))]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2005;48(7):803–12. doi: 10.1007/s00103-005-1071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharma N, Singh D, Sobti A, Agarwal P, Velpandian T, Titiyal JS, et al. Course and outcome of accidental sodium hydroxide ocular injury. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(4):740–9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ballantyne B, Myers RC, Losco PE. The acute toxicity and primary irritancy of 1-propoxy-2-propanol. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1988;30(2):126–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gilpin S, Hui X, Maibach H. In vitro human skin penetration of geraniol and citronellol. Dermatitis. 2010;21(1):41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Juarez A, Goiriz R, Sanchez-Perez J, Garcia-Diez A. Disseminated allergic contact dermatitis after exposure to a topical medication containing geraniol. Dermatitis. 2008;19(3):163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hagvall L, Backtorp C, Svensson S, Nyman G, Borje A, Karlberg AT. Fragrance compound geraniol forms contact allergens on air exposure. Identification and quantification of oxidation products and effect on skin sensitization. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20(5):807–14. doi: 10.1021/tx700017v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zahlsen K, Eide I, Nilsen AM, Nilsen OG. Inhalation kinetics of C8 to C10 1-alkenes and iso-alkanes in the rat after repeated exposures. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;73(3):163–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.National Toxicology Program. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of coconut oil acid diethanolamine condensate (CAS No. 68603-42-9) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice (dermal studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser. 2001;479:5–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rossbach B, Kegel P, Letzel S. Application of headspace solid phase dynamic extraction gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (HS-SPDE-GC/MS) for biomonitoring of n-heptane and its metabolites in blood. Toxicol Lett. 2012;210(2):232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bahima J, Cert A, Menendez-Gallego M. Identification of volatile metabolites of inhaled n-heptane in rat urine. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984;76(3):473–82. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gharsallah H, Lamine K, Hajjaj Z, Nasri M, Ferjani M. [Exposure to butane gas and hyperbaric oxygenation therapy]. Tunis Med. 2010;88(1):63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brared Christensson J, Andersen KE, Bruze M, Johansen JD, Garcia-Bravo B, Gimenez Arnau A, et al. Air-oxidized linalool: a frequent cause of fragrance contact allergy. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;67(5):247–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2012.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Christensson JB, Matura M, Gruvberger B, Bruze M, Karlberg AT. Linalool–a significant contact sensitizer after air exposure. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62(1):32–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]