Abstract

Background

Approximately 12% of operations for traumatic neuropathy are for patients with segmental nerve loss and less than 50% of these injuries obtain meaningful functional recovery. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) therapy has been shown to improve functional outcomes after nerve severance and we hypothesized this therapy could also benefit nerve autografting.

Methods

A segmental rat sciatic nerve injury model was used, whereby a 0.5 cm defect was repaired with an autograft using microsurgery. Experimental animals were treated with solutions containing methylene blue (MB) and PEG; control animals did not receive PEG. Compound Actions Potentials (CAPs) were recorded before nerve transection, after solution therapy, and at 72 hours postoperatively. The animals underwent behavioral testing at 24 and 72 hours postoperatively. After sacrifice, nerves were fixed, sectioned, and immunostained to allow for quantitative morphometric analysis.

Results

The introduction of hydrophilic polymers greatly improved morphological and functional recovery of rat sciatic axons at 1–3 days following nerve autografting. PEG therapy restored CAPs in all animals and CAPs were still present 72 hours postoperatively. No CAPS were detectable in control animals. Footfall asymmetry scores and sciatic functional index scores were significantly improved for PEG therapy group at all time points (p <0.05 and p<0.001; p <0.001 and p <0.01). Sensory and motor axon counts were increased distally in nerves treated with PEG compared to control (p = 0.0189 and p = 0.0032).

Conclusions

PEG therapy improves early physiologic function, behavioral outcomes, and distal axonal density after nerve autografting.

Keywords: traumatic neuropathy, hydrophilic polymers, nerve graft, axonal repair, methylene blue, polyethylene glycol, axonal fusion, nerve fusion

Introduction

Axonal fusion has been reported as a natural mechanism utilized by invertebrates to promote very rapid and highly specific neuronal recovery of complex behaviors after injury [1,2]. Hydrophilic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) have also been shown to rejoin the axolemma of the cut ends of severed proximal and distal axons inducing both morphological and functional axonal continuity (PEG-fusion) [3–6]. Scientists have been used PEG for decades to fuse cells to immortalize desired cell lines such as monoclonal antibody producing B-cells [7].

PEG facilitates lipid bilayer fusion by removing water from membrane bound proteins at or near the damage site, decreasing the activation energy required for plasmalemmal leaflets to fuse [8,9]. These same properties of PEG help to restore functional connections between proximal axonal segments connected to their cell bodies and distal severed axons [3–6,10]. Specifically, within 1–2 minutes after cut or crush severance, PEG has been used in vitro to rapidly reconnect the severed proximal and distal halves of individually-identified invertebrate giant axons as measured by intra-axonal dye diffusion [10].

Most recently, PEG has been used to rapidly restore axonal morphological and physiological continuity of cut- or crushed- severed mammalian sciatic nerves in vitro, ex vivo and/or in vivo [3–6,11,12]. Recent studies have also demonstrated that PEG has a neuroprotective effect after acute spinal cord injury in the rat model [5,13]. No study has been performed, however, utilizing PEG combined with other procedures to restore morphologic or physiologic continuity after segmental nerve loss treated with nerve autografting. If successful, the ability to fuse severed nerves with exogenous application of PEG and regain rapid functional recovery has the potential to produce a paradigm shift in therapeutic management following peripheral nerve damage.

Sealing of axolemmal damage normally occurs through a calcium-dependent accumulation of membranous structures that interact with nearby undamaged membrane to form a seal [14–16]. Calcium also initiates processes leading to cell death and axonal Wallerian degeneration (breakdown of the axon distal to the site of injury) within 48–96 hours after injury [9,17]. In severed nerves, this calcium-dependent system for plasmalemmal repair, seals the cut ends of partially-collapsed axons with vesicles, preventing them from possibly fusing with an adjacent open axonal stump [5,6].

Our protocol includes irrigating the site of nerve injury prior to PEG-fusion in a calcium free, isotonic, isosmotic solution to open axonal ends and remove vesicles. The antioxidant Methylene Blue (MB) is also added prior to adding PEG to reduce vesicle formation [5]. After adding PEG to induce PEG-fusion of open, vesicle-free axonal ends, the PEG is washed away by isotonic saline containing calcium so that vesicles form to seal any remaining holes [3–6,9,14,15]. We hypothesize that this therapy will restore nerve electrophysiology after interposition autografting leading to improved behavioral outcomes.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the standards set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Female Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with inhaled isoflourane and the left hindlimb shaved with clippers and prepped aseptically. A two cm incision was made parallel, and just caudal, to the femur. Using sharp dissection, the cephalad border of the biceps femoris was freed to allow for caudal retraction and exposure of the left sciatic nerve. This exposure allows for visualization of the entire sciatic nerve without the need for muscle division. The exposed nerve was then dissected free of perineural tissue using sharp dissection and minimal retraction. The exposed nerve was bathed in Plasma-lyte A® (Baxter: Deerfield, IL) and electrophysiological testing was performed. Plasma-lyte A® is a calcium free solution containing the following (in mEq/L): Na 140, K 5, Mg 3, Cl 98, Acetate 27, Gluconate 23. The solution is at pH 7.4 and contains 294 mOsm/L.

A 5 mm segment of sciatic nerve was then removed and the wound was irrigated with Plasma-lyte A®. Using standard microsurgical techniques, with careful attention paid to maintain orientation, the removed segment of sciatic nerve was sutured in place using 9-0 Ethilon (Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ). Once both ends were approximated in an end-to-end fashion using an interrupted suturing technique and microscopic magnification, a hypotonic 1% solution of MB (Acros Organics; Morris Plains, NJ) in sterile water was applied to the coaptation sites for one minute. A 50% by weight solution of PEG (3.35kD molecular weight, Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) in sterile water was then applied to the coaptation sites for 1 minute in experimental animals. Control animals received a solution containing only sterile water.

The wound was then irrigated with Lactated Ringers (Hospira; Lake Forest, IL) and electrophysiological testing was repeated. Lactated Ringers contains the following (in mEq/L): Na 130, K 4, Ca 2.7, Cl 109, and Lactate 28. This isotonic, calcium-containing solution is at pH 6.5 and has 273 mOsm/L. The skin was approximated using a running subcuticular 5-0 monocryl suture (Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ). All control and experimental animals were then given a subcutaneous injection of ketoprofen (5mg/kg) and allowed to emerge from anesthesia. Ketoprofen is almost completely excreted by 24 hours postoperatively, having minimal, if any, impact on behavioral testing occurring after that time point [18].

At 72 hours postoperatively, after behavioral testing had been completed, the rats were again anesthetized with inhaled isoflourane and the left hindlimb was prepared as previously described. Using the same exposure technique, the left sciatic nerve was exposed. The wound was irrigated with Plasma-lyte A® and electrophysiological testing was repeated.

The rat was then sacrificed via intracardiac injection of Fatal-Plus Solution (Vortech, Dearborn, MI). Bilateral sciatic nerves were harvested immediately after sacrifice and placed into 10% neutral buffered formalin. For electrophysiological testing and behavioral testing, 10 rats were in the experimental group and 10 rats were in the control group. For histological testing, 5 rats were used in the experimental group and 5 rats were used in the control group.

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL TESTING

Compound Action Potentials (CAPs) are a measure of axonal continuity. All CAPs were then obtained using a Powerlab Data Acquisition System (ADInstruments; Colorado Springs, CO) interfaced with Scope™ 4 (ADInstruments; Colorado Springs, CO). One dual-terminal hook electrode was placed under both the proximal and distal end of the exposed nerve. The proximal electrode was used to deliver an electrical stimulus and the distal electrode was used to record the stimulus and CAPs. CAPs were recorded prior to nerve transection (baseline), immediately after solution therapy, and at 72 hours postoperatively.

BEHAVIORAL TESTING

Behavioral assessments were performed at 24 hours and 72 hours postoperatively. Animals were not tested earlier to allow for adequate recovery from anesthesia and to minimize the potential confounding effects of ketoprofen administration at the time of surgery.

Foot Fall Asymmetry Score

Animals were allowed to roam freely on a wire mesh grid measuring 45 cm × 30 cm, with square openings measuring 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm. The grid was elevated 2 cm above a solid base. Trials for each animal were recorded for 50 total steps per hindlimb. A foot fault was scored when a step resulted in the hindlimb falling through the opening in the grid, touching the floor. If the hindlimb was retracted after falling through the grid opening, but prior to touching the floor, the step was scored as a partial fault. A composite fault score was calculated using the previously reported methods [4,19]. The following equations were used:

Composite Foot Fault score = (# Partial Faults × 1) + (# Full Faults × 2)

% Foot Fault = (Composite Foot Fault score/ total number of steps) × 100%

Foot Fault Asymmetry Score = % Foot Fault (normal hindlimb) − % Foot Fault (surgical hindlimb)

Sciatic Functional Index

Gait analysis has been used previously to measure outcomes after sciatic nerve severance or injury [20–23]. Rats are trained to walk across a beam to a cage. This requires a few trials, as rats will initially pause frequently en route to the cage. After these habituation trials, the rats traversed the beam to the cage without hesitation. For each trial run, a strip of white receipt paper is secured to the wooden beam for data collection. The hind limbs are preferentially inked (in our experiments red designated the surgical limb and black the normal limb) and the animals were placed on the end of the beam farthest from the cage. Three consecutive footprints from each limb (total of six) were used to measure the following: normal print length (NPL), normal toe spread (NTS), normal intermediary toe spread (NIS), experimental print length (EPL), experimental toe spread (ETS), and experimental intermediary toe spread (EIS). Intermediary toe spread was measured from toes two to four and toe spread was measured from toe one to five. Sciatic functional index (SFI) scores were then calculated using mean values entered into the following formula [22,24] :

SFI scores of −100 indicate complete functional impairment of the sciatic nerve and scores of approximately 0 are at the level of complete function of the sciatic nerve [20,22,24].

HISTOLOGY

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using commercial antibodies specifically directed against Carbonic Anhydrase II (CA2) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and Choactase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Carbonic Anhydrase II staining is positive in sensory neurons and Choactase staining is positive in motor neurons [17,25–29]. Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm, placed on slides and warmed overnight at 60°C. Slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated with graded alcohols ending in Tris buffered saline (TBS-T Wash Buffer, LabVision, Freemont, CA). For CA2, heat mediated target retrieval was performed in 1X Target Retrieval Buffer (pH 9.0, DAKO, Carpenteria, CA). Endogenous peroxidases and non-specific background were blocked by subsequent incubations in 3% H2O2 (Fisher, Suwanee, GA) in TBS-T and serum-free Protein Block (RTU, DAKO). Primary antibody to CA2 was used at 1:4000 for 1 hour, followed by incubation in EnVision+ HRP Labelled Polymer (RTU, DAKO).

For Choactase staining, no target retrieval was required. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked as before. Non-specific background, secondary, and tertiary labeling of target was accomplished by use of Vector’s ABC Elite Goat IgG kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Primary antibody to Choactase was used at 1:35 for 1 hour. Slides were rinsed with TBS-T between each reagent treatment and all steps were carried out at room temperature unless otherwise noted. Visualization was achieved with DAB+ chromogen (DAKO). Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, dehydrated through a series of alcohols and xylenes, and then coverslipped with Acrytol Mounting Media (Surgipath, Richmond, IL).

Light Microscopy

All stained slides were examined using an Olympus Vanox-T AH-2 light microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) interfaced to Pixera Pro 600 HS digital camera (Pixera Corporation; Santa Clara, CA). Multiple digital photomicrographs were captured at 10 × using Viewfinder V3.0.1 (Pixera Corporation; Santa Clara CA). For each nerve processed, representative cross sections were photographed proximal to the site of injury, from the autograft used to repair the defect, and distally from the sciatic nerve. To count axons the number of stained axons on each photomicrograph, ImageJ v1.45 software combined with the Wright Cell Imaging Facility plug-in package was used in a method that has been previously reported [30,31]. The total number of axons per cross section were determined by adding the axon totals from all representative photomicrographs or a given cross section; care was taken to avoid double counting axons.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software; San Deigo, CA). To compare CAPs from all groups a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test was performed. Specific CAPs comparisons were completed with a student’s t-test, where appropriate. With regard to foot fault asymmetry scores and the sciatic functional index, a two way ANOVA with the Bonferroni multiple comparison method was employed to specifically compare treatment and control groups. For comparison of axon counts Student’s t-test was used to compare specific groups. All p values were 2-tailed, where appropriate, and significance was determined at p < .05.

Results

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY DATA

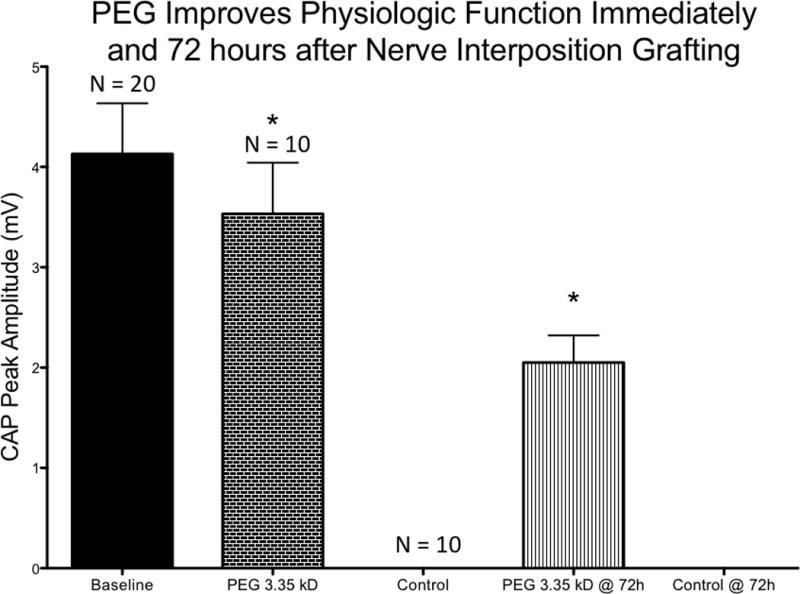

Electrophysiological testing revealed no significant difference in baseline CAPs and CAPS recorded post injury for animals treated with PEG (Figure 1). Baseline CAPs were present in all animals (mean 4.131 ± 2.25 mV, minimum 1.87 mV, maximum 8.24 mV; n= 20) and the combined results are shown (Figure 1). Individually, no statistically significant differences were detected between baseline CAPs in the experimental (mean 4.127 ± 2.19 mV, min 2.15 mV, max 7.989 mV) or control groups (mean 4.134 ± 2.43 mV, min 1.87 mV, max 8.24 mV) prior to neurotomy. Immediately after nerve transection and repair CAPs could not be obtained in any control animals (n=10). Additionally, no CAPS could be recorded in control animals (n=10) 72 hours after nerve transection and repair. By contrast, CAPs were found in all PEG treated animals immediately and 72 hours after nerve transection and repair (mean 3.533 ± 1.61 mV, min 1.206 mV, max 5.741 for immediate group and 2.051 ± .857 mV, min 1.37 mV, max 4.25, at 72 hours; n = 10). Thus, the PEG treated group exhibited significantly improved CAPs compared to control at both time points (p < 0.001 immediately and p < 0.001 at 72 hours). While there was no statistically significant difference between baseline and immediate PEG CAPs (p = 0.46), those obtained in the PEG group at 72 hours were significantly (p = .009) smaller compared to baseline CAPs. Additionally, PEG CAP values were higher immediately after repair than at 72 hours after repair by a statistically significant margin (p = 0.019).

Figure 1.

PEG treatment groups demonstrated statistically significant physiological recovery compared to the control group immediately and at 72 hours (p <.05). Baseline n=20, PEG 3.35 kD n=10, Control n=10, PEG 3.35 kD @72h n=10, Control @ 72h n=10

BEHAVIORAL DATA

Foot Fall Asymmetry Score

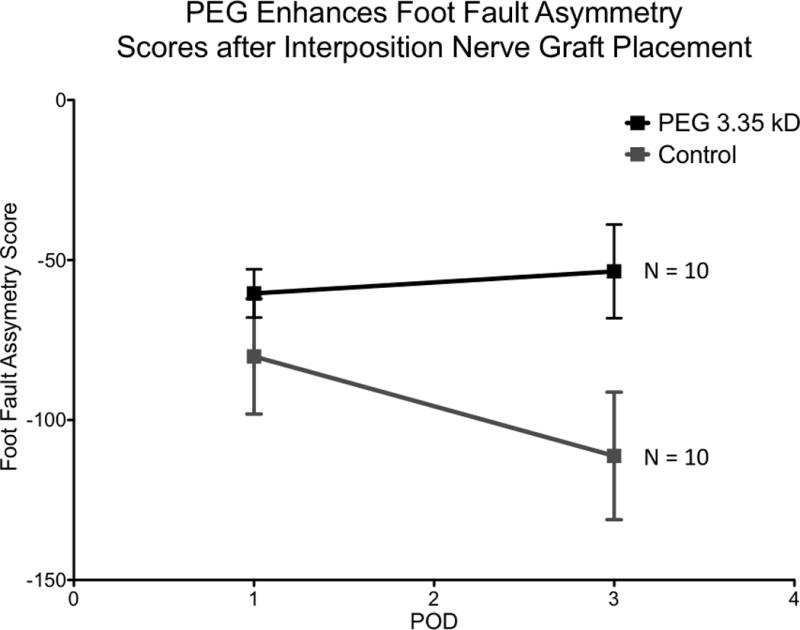

Footfall asymmetry scores were significantly improved for PEG therapy group at all time points (p <0.05 on postoperative day 1 and p<0.001 on postoperative day 3) (Figure 2). Control values for footfall asymmetry scores for postoperative day 1 had a mean value of −80 ± 18 (min −106, max −58) and for postoperative day 3 had a mean value of −111 ± 20 (min −144, max −84). The PEG treated group values for footfall asymmetry scores for postoperative day 1 had a mean value of −53 ± 22 (min −84, max −36) and for postoperative day 3 had a mean value of −53 ± 14 (min −78, max −28).

Figure 2.

PEG 3.35 kD significantly improves sciatic nerve function compared to control on postoperative day 1 and 3 (p<.05 and p<.0001, respectively). PEG 3.35 kD n= 10, Control n=10

In the control group, performance on postoperative day 3 was worse than performance on postoperative day 1 by a statistically significant margin (p = 0.0163). No statistically significant difference between performance of the PEG treated group on postoperative day 1 and 3 was detected (p = 1).

Sciatic Functional Index

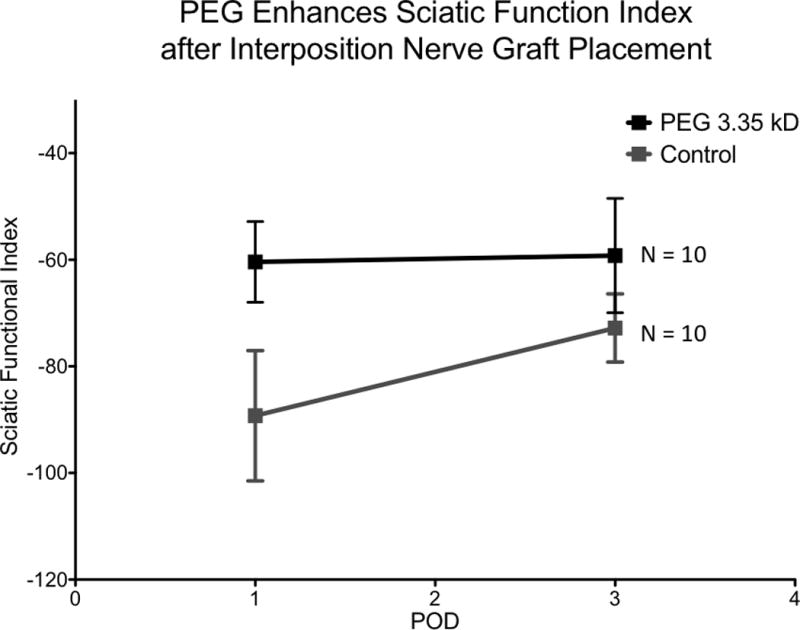

The sciatic functional index was significantly improved in the PEG treated group on postoperative days one and three compared to the control group (p <0.001 and p <0.01, respectively) (Figure 3). Control values for SFI for postoperative day 1 had a mean value of − 89 ± 12 (min −100, max −72) and for postoperative day 3 had a mean value of −73 ± 6 (min −84, max −62). The PEG treated group values for SFI on postoperative day 1 had a mean value of −60 ± 8 (min −69, max −50) and for postoperative day 3 had a mean value of −59 ± 11 (min −72, max −42). For the control group, performance on postoperative day 3 was worse than performance on postoperative day 1 (p = .002). There was no statistically significant difference between performances of the PEG treated group on postoperative day 1 and 3 (p = .8214).

Figure 3.

PEG 3.35 kD significantly improves sciatic nerve function compared to control on postoperative day 1 and 3 (p<.0001 and p<.01, respectively). (PEG 3.35 kD n= 10, Control n=10)

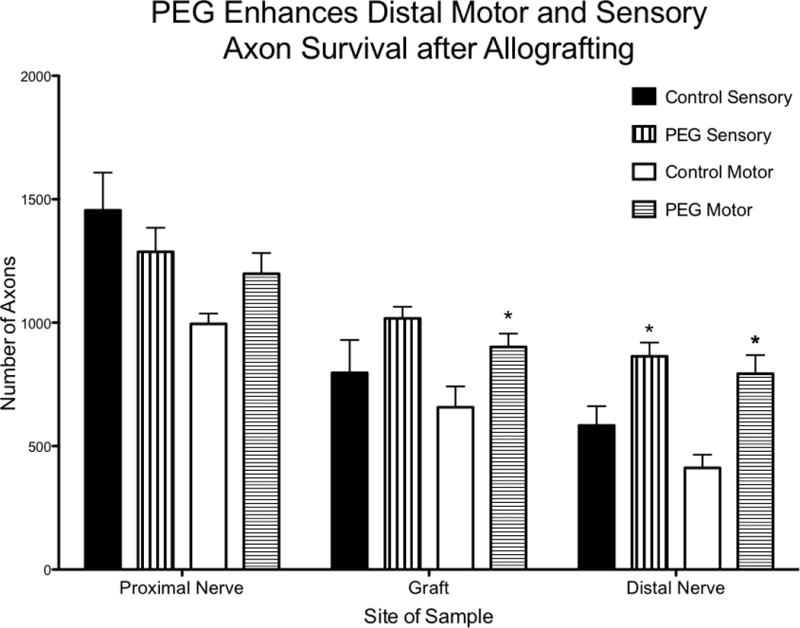

HISTOLOGICAL DATA

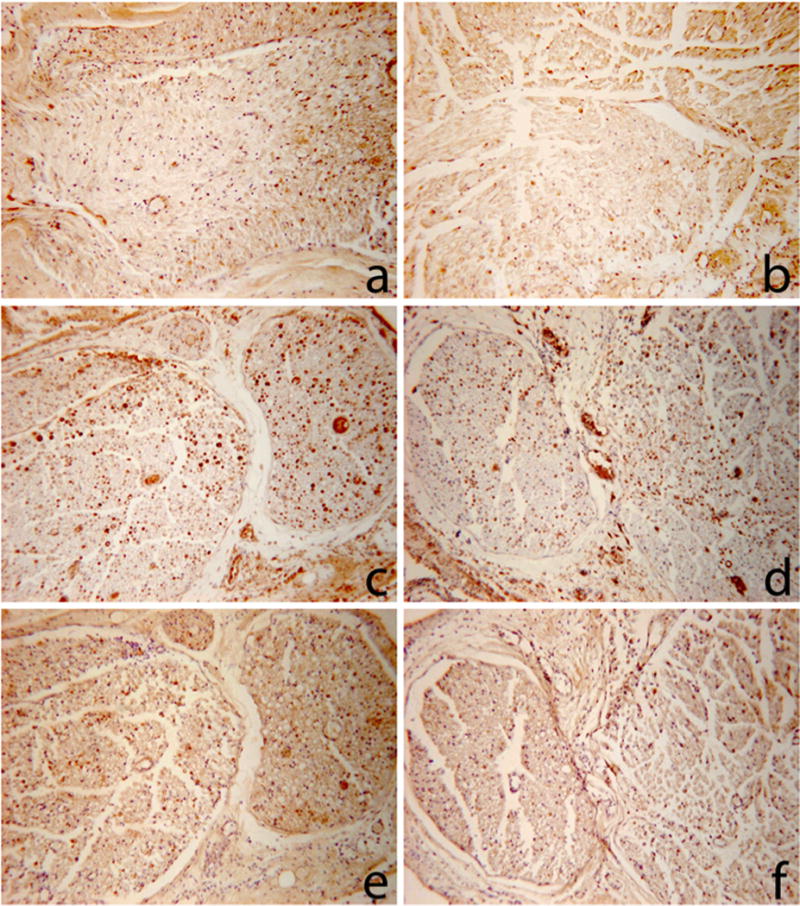

Sensory and motor axon counts were increased distally in nerves treated with PEG compared to control (p = 0.0189 and p = 0.0032, respectively) (Figure 4). The number of Choactase positive motor axons were increased in PEG treated autografts compared to control (p = 0.041) (Figure 4). Representative photomicrographs of these nerve segments are demonstrated in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Axonal counts for cross sections of proximal sciatic nerve, nerve allograft, and distal sciatic nerve. There was a statistically significant difference in the number of motor axons in the grafts of animals treated with PEG compared to control (p = .041). There was also a statistically significant difference in the distal sensory and motor axon count in animals treated with PEG compared to control (p = .0189 and p = .0032, respectively). PEG treated n=5 and control n=5.

Figure 5.

Representative photomicrographs of nerve cross sections used for the counts generated in Table 1.

a: PEG graft stained for Choactase

b: control graft stained for Choactase

c: PEG distal nerve stained for Carbonic Anhydrase II

d: control distal nerve stained for Carbonic Anhydrase II

e: PEG distal nerve stained for Choactase

f: control distal nerve stained for Choactase

Representative sections c and e are directly in series, as are representative sections d and f to demonstrate the different distribution of sensory and motor axons.

There was no statistically significant difference in proximal sensory or motor axonal counts in the PEG treated group compared to control (p = .379 and p = 0.0625). All groups demonstrated a steady decrease in the number of Carbonic Anhydrase II positive (sensory) and Choactase positive (motor) axons counted as increasingly distal axons were assessed along the nerve (i.e. proximal counts > autograft counts > distal counts) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Axonal counts from Choactase and Carbonic Anhydrase II staining. Choactase staining is positive in motor nerves, Carbonic Anhydrase II staining is positive in sensory nerves.

| Choactase Staining | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axon Count | PEG Proximal | PEG Graft | PEG Distal | Control Proximal | Control Graft | Control Distal |

| Mean ± SD | 1198 ± 188 | 901 ± 121 | 793 ± 168 | 995 ± 95 | 658 ± 189 | 412 ± 118 |

| Minimum | 940 | 740 | 625 | 844 | 510 | 313 |

| Maximum | 1377 | 1005 | 985 | 1096 | 984 | 567 |

| Carbonic Anhydrase II Staining | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axon Count | PEG Proximal | PEG Graft | PEG Distal | Control Proximal | Control Graft | Control Distal |

| Mean ± SD | 1287 ± 218 | 1017 ± 105 | 864 ± 124 | 1455 ± 340 | 797 ± 298 | 583 ± 175 |

| Minimum | 982 | 893 | 696 | 1026 | 536 | 397 |

| Maximum | 1556 | 1118 | 1040 | 1937 | 1196 | 811 |

Discussion

Prior electrophysiological studies of distal nerve segments after cut severance in rats revealed that most distal stumps, when stimulated directly, will fail to conduct CAPs by 24 hours and all failed to conduct CAPs at 36 hours [32]. The data presented in this report suggest that PEG fused autografts have delayed this process. In accordance with our experimental design, CAPs were stimulated proximal to the site injury and conducted through an autograft and recorded in the distal axonal segment. These experiments demonstrate that PEG-based axonal fusion can be an effective repair strategy for early restoration of nerve electrophysiology and improvement in early behavioral outcomes after nerve autografting.

Cessation of CAP conduction by a nerve and failure of transmission across the neuromuscular junction are among the earliest signs of axonal injury [33–36]. Previous reports have demonstrated CAP conduction after PEG fusion through a single site of crush severance or transection injury, however, to our knowledge this is the first report of immediate restoration of CAP conductance across a nerve graft [3,4,6].

Peripheral nerve injury is common, occurring in over 17,500 cases annually in the United States alone [37,38]. Current strategies for peripheral nerve repair are severely limited. Techniques such as nerve grafts, tissue matrices, and nerve growth guides have been designed to enhance the number of axons regenerating by outgrowths from surviving distal stumps [43]. Unfortunately, even with such advanced techniques, it can take months for regenerating axons to reach denervated target tissues when injuries are proximally located [43,44]. Current nerve repair strategies are based on enhancement of axonal outgrowth because all axons distal to a site of injury undergo Wallerian degeneration [17,37,43].

Wallerian degeneration occurs in sites of axonal disruption, and is the process whereby the distal axonal end degenerates and fragments [36]. This process occurs more quickly in nerves after cut-severance, than with crush-severance and begins within hours of injury [33,43]. Wallerian degeneration can be seen in proximal nerve segments depending upon the severity of injury [43]. In rodents, there is a short lag time of 24 to 48 hours where the distal stump is largely unaltered histologically, followed by rapid degradation and remodeling of the distal axonal segment [45]. The data shown in Figure 4, taken at 72 hours post injury, suggests that this process in PEG fused autografts is delayed. Furthermore, we report early improvement of behavioral measures in PEG treated animals on postoperative days 1 and 3 compared to control (Figures 3 and 4). Although walking track analyses can be compromised by many factors [21–24,46], after sciatic nerve injury PEG fusion repair of simple crush or cut injured axons have shown similar behavioral improvements [4,6].

Taken together, the physiological, behavioral, and immunohistochemical data presented in this manuscript are all consistent with the conclusion that PEG-fusion of a nerve autograft improves early functional recovery. Previously, the inability to rapidly restore the loss of function after axonal injury combined with non-specific innervation of target tissues continues to produce poor clinical outcomes [47]. Moreover, amputation rather than repair or replantation remains a widely accepted indication in circumstances of either mutilating lower extremity injuries or devascularized upper arm injuries with nerve injuries involving loss of a nerve segment [37].

This is a noteworthy advancement, implying that this treatment regimen can delay Wallerian degeneration of distal axons after acute nerve injury, even in cases of severe nerve injury with nerve gaps produced by removing nerve segments. Although the present study has been restricted to manipulation of rat axons after severance, we envision that this line of investigation will eventually find its application in human nerve injury. Specifically, this technique involves the use of current microsurgical techniques, with the simple addition of FDA approved irrigating solutions; it could rapidly be incorporated into the standard human neurorrhaphy regimen.

By avoiding the current delays in recovery associated with axonal outgrowth, patients may experience more immediate and overall improved outcomes. Such a therapeutic regime could prove particularly relevant for patients with proximal nerve injuries where even if the nerve is repaired, motor recovery is rare. This devastating outcome occurs because irreversible muscle atrophy occurs after 12 + months of loss of innervation. Since the rate of axonal outgrowth after standard neurorrhaphy techniques is only 1 mm per day, for proximal neuronal injuries such as brachial plexus or spinal cord injuries, which are over 30 cm from the motor endplate, reinnervation occurs too late for functional recovery. This PEG fusion strategy has the potential for expansion to any site of peripheral nerve injury and could provide a practical and economical solution for injuries that are currently devastating. Since many nerve injuries involve segmental nerve injury with nerve gaps, the ability to use nerve grafts in conjunction with the PEG fusion technique is a critical advancement for the translation of this repair strategy toward clinical applicability.

We are currently focusing on expanding this PEG fusion technique using allografts over autografts and for cases involving larger nerve gaps. We have plans to include porcine animal models to validate the technique in larger mammals with longer nerve gaps prior to translation into clinical studies.

Limitations

Our data were limited in that CAP amplitude was shown to decrease immediately and at 72 hours compared to baseline levels suggesting ongoing axonal loss. (Figure 1) Axon counts, also decreased as one progressed distally through the nerve. Both of these demonstrate that axonal fusion in autografts is not a complete, immediate, permanent process. Additionally, after severance and repair with allografting, it is impossible that standard suture repair and PEG fusion would allow all axons to align exactly at the proximal and distal sites of coaptation. The true percentage of axons that fuse and remain viable long term is unknown, however, the literature reports that if 10–15% of axons survive, significant behavioral recovery can be seen [48,49]. The axonal counts reported in this manuscript demonstrate differences greater than 15% difference in the PEG graft and distal counts compared to control. This supports what we report, however further work needs to be done to determine the long term effects of PEG fusion on allografts to see if the effects are permanent as with PEG fused nerves after cut-severance and suture repair [6].

Rodent models are commonly used to examine events and mechanisms associated with peripheral nerve injury and repair [22]. At present, our model is relevant to nerve injuries sustained during an operation because this injury is amenable to immediate repair. This model does not mimic the case of traumatic injuries where repair is rarely, if ever, immediately available. Another limitation in our study is that in the rat sciatic nerve transection model, the length of the distal axon stump is much shorter than that of typical human injuries. Larger animal studies are planned to evaluate PEG fusion in larger mammals. We have however demonstrated the proof-of-principle that outcomes following peripheral nerve grafting can be enhanced by a PEG mediated fusion protocol. Further work will be necessary to determine the effect of hydrophilic polymers when nerve repair is delayed to mimic traumatic scenarios.

In summary, our current studies are focused on expanding this PEG fusion technique to include the testing with allografts to build on the foundational work with autografts as reported in this manuscript. Additional studies are also needed to determine whether more lengthy nerve gaps will also exhibit preservation in CAPs and other evidence of motor and sensory restoration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Colleen M. Brophy, M.D. for her expert review of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Neumann B, Nguyen KCQ, Hall DH, Ben-Yakar A, Hilliard MA. Axonal regeneration proceeds through specific axonal fusion in transected C. elegans neurons. Dev Dyn. 2011 Jun.240(6):1365–1372. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deriemer SA, Elliott EJ, Macagno ER, Muller KJ. Morphological evidence that regenerating axons can fuse with severed axon segments. Brain Res. 1983 Aug.272(1):157–161. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lore AB, Hubbell JA, Bobb DS, Ballinger ML, Loftin KL, Smith JW, et al. Rapid induction of functional and morphological continuity between severed ends of mammalian or earthworm myelinated axons. J Neurosci. 1999 Apr.19(7):2442–2454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02442.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britt JM, Kane JR, Spaeth CS, Zuzek A, Robinson GL, Gbanaglo MY, et al. Polyethylene glycol rapidly restores axonal integrity and improves the rate of motor behavior recovery after sciatic nerve crush injury. J Neurophysiol. 2010 Aug.104(2):695–703. doi: 10.1152/jn.01051.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaeth C, Robinson T, Fan J, Bittner G. Cellular mechanisms of plasmalemmal sealing and axonal repair by polyethylene glycol and methylene blue. J Neurosci Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jnr.23022. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bittner G, Keating C, Kane J, Britt J, Spaeth C, Fan J, et al. Rapid, effective and long-lasting behavioral recovery produced by microsutures, methylene blue and polyethylene glycol after complete cut of rat sciatic nerves. J Neurosci Res. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jnr.23023. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975 Aug.256(5517):495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramon Y, Cajal S. In: Degeneration & Regeneration of the Nervous System. May Raoul M., editor. Hafner Publishing Co.; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen MP, Bittner GD, Fishman HM. Critical interval of somal calcium transient after neurite transection determines B 104 cell survival. J Neurosci Res. 2005 Sep.81(6):805–816. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krause TL, Bittner GD. Rapid morphological fusion of severed myelinated axons by polyethylene glycol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Feb.87(4):1471–1475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzullo T, Britt J, Stavisky R, Bittner G. Cooling enhances in vitro survival and fusion-repair of severed axons taken from the peripheral and central nervous systems of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;327(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stavisky R, Britt J, Zuzek A, Truong E, Bittner G. Melatonin enhances the in vitro and in vivo repair of severed rat sciatic axons. Neurosci Lett. 2005;376(2):98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon BK, Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Emerging repair, regeneration, and translational research advances for spinal cord injury. Spine. 2010 Oct.35(21 Suppl):S263–70. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f3286d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause TL, Fishman HM, Bittner GD. Axolemmal and septal conduction in the impedance of the earthworm medial giant nerve fiber. Biophys J. 1994 Aug.67(2):692–695. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80528-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spaeth CS, Boydston EA, Figard LR, Zuzek A, Bittner GD. A Model for Sealing Plasmalemmal Damage in Neurons and Other Eukaryotic Cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(47):15790–15800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4155-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo S, Nguyen MP, Fukuda M, Bittner GD, Fishman HM. Plasmalemmal sealing of transected mammalian neurites is a gradual process mediated by Ca(2+)-regulated proteins. J Neurosci Res. 2003 Nov.74(4):541–551. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SK, Wolfe SW. Peripheral nerve injury and repair. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000 Jul-Aug;8(4):243–252. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantor TG. Ketoprofen: a review of its pharmacologic and clinical properties. Pharmacotherapy. 1986 Apr.6(3):93–103. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1986.tb03459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Šedý J, Urdzíková L, Jendelová P, Syková E. Methods for behavioral testing of spinal cord injured rats. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008 Jan.32(3):550–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Medinaceli L, Freed WJ, Wyatt RJ. An index of the functional condition of rat sciatic nerve based on measurements made from walking tracks. Exp Neurol. 1982 Sep.77(3):634–643. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinh P, Hazel A, Palispis W, Suryadevara S, Gupta R. Functional assessment after sciatic nerve injury in a rat model. Microsurgery. 2009;29(8):644–649. doi: 10.1002/micr.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols C, Myckatyn T, Rickman S, Fox I, Hadlock T, Mackinnon S. Choosing the correct functional assay: A comprehensive assessment of functional tests in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2005;163(2):143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozkurt A, Deumens R, Scheffel J, O’Dey DM, Weis J, Joosten EA, et al. CatWalk gait analysis in assessment of functional recovery after sciatic nerve injury. J Neurosci Meth. 2008 Aug.173(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bain JR, Mackinnon SE, Hunter DA. Functional evaluation of complete sciatic, peroneal, and posterior tibial nerve lesions in the rat. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1989 Jan.83(1):129–138. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198901000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawasaki Y, Yoshimura K, Harii K, Park S. Identification of myelinated motor and sensory axons in a regenerating mixed nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25A(1):104–111. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2000.jhsu025a0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley DA, Sanger JR, Matloub HS, Yousif NJ, Bain JLW, Moore GH. Identifying motor and sensory myelinated axons in rabbit peripheral nerves by histochemical staining for carbonic anhydrase and cholinesterase activities. Brain Research. 1988 Jun.453(1–2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cammer W, Tansey FA. Immunocytochemical localization of carbonic anhydrase in myelinated fibers in peripheral nerves of rat and mouse. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 1987;35(8):865. doi: 10.1177/35.8.3110266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badia J, Pascual-Font A, Vivó M, Udina E, Navarro X. Topographical distribution of motor fascicles in the sciatic-tibial nerve of the rat. Muscle Nerve. 2010 Apr.42(2):192–201. doi: 10.1002/mus.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lago N, Navarro X. Correlation between target reinnervation and distribution of motor axons in the injured rat sciatic nerve. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2006 Feb.23(2):227–240. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abràmoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics international. 2004;11(7):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marina N, Bull ND, Martin KR. A semiautomated targeted sampling method to assess optic nerve axonal loss in a rat model of glaucoma. Nat Protoc. 2010 Sep.5(10):1642–1651. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miledi R, CRS On the degeneration of rat neuromuscular junctions after nerve section. The Journal of Physiology. 1970 Apr.207(2):507. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lunn E, Brown M, Perry V. The Pattern of Axonal Degeneration in the Peripheral Nervous-System Varies with Different Types of Lesion. Neuroscience. 1990;35(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90130-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilliatt R. Nerve conduction during Wallerian degeneration in the baboon. J Neurol. 1972 doi: 10.1136/jnnp.35.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Wallerian degeneration in human nerves: Serial electrophysiological studies. Muscle Nerve. 1992 Jun.15(6):687–693. doi: 10.1002/mus.880150610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koeppen AH. Wallerian degeneration: history and clinical significance. J Neurol Sci. 2004 May.220(1–2):115–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfe SW, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Kozin SH. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. Vol. 5 Churchill Livingstone; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang JR, Zamorano DP, Gupta R. Limb salvage with major nerve injury: current management and future directions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S28–34. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201102001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holcomb JB, McMullin NR, Pearse L, Caruso J, Wade CE, Oetjen-Gerdes L, et al. Causes of death in U.S. Special Operations Forces in the global war on terrorism: 2001–2004. Annals of Surgery. 2007 Jun.245(6):986–991. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000259433.03754.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kragh JFJ, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Fox CJ, Wade CE, Salinas J, et al. Survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. Ann Surg. 2009 Jan.249(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818842ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isaacson BM, Weeks SR, Pasquina PF, Webster JB, Beck JP, Bloebaum RD. The road to recovery and rehabilitation for injured service members with limb loss: a focus on Iraq and Afghanistan. US Army Med Dep J. 2010 Jul-Sep;:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cross JD, Ficke JR, Hsu JR, Masini BD, Wenke JC. Battlefield orthopaedic injuries cause the majority of long-term disabilities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(Suppl 1):S1–7. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201102001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell WW. Evaluation and management of peripheral nerve injury. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008 Sep.119(9):1951–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanec S, Tonković I, Stanec Z, Tonković D, Dzepina I. Treatment of upper limb nerve war injuries associated with vascular trauma. Injury. 1997 Sep.28(7):463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(97)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glass J, Culver D, Levey A, Nash N. Very early activation of m-calpain in peripheral nerve during Wallerian degeneration. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiaveto de Souza A, da Silva CA, Del Bel EA. Methodological Evaluation to Analyze Functional Recovery after Sciatic Nerve Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2004 May.21(5):627–635. doi: 10.1089/089771504774129955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans PJ, Bain JR, Mackinnon SE, Makino AP, Hunter DA. Selective reinnervation: a comparison of recovery following microsuture and conduit nerve repair. Brain Res. 1991 Sep.559(2):315–321. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eidelberg E, Straehley D, Erspamer R, Watkins CJ. Relationship between residual hindlimb-assisted locomotion and surviving axons after incomplete spinal cord injuries. Exp Neurol. 1977 Aug.56(2):312–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(77)90350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kakulas BA. A review of the neuropathology of human spinal cord injury with emphasis on special features. J Spinal Cord Med. 1999;22(2):119–124. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1999.11719557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]