Abstract

Objectives

Black men who have sex with men and women (MSMW) experience high HIV rates and may not respond to interventions targeting gay-identified men. We tested the efficacy of the Men of African American Legacy Empowering Self (MAALES), a multi-session, small-group, holistically-framed intervention designed to build skills, address sociocultural issues and reduce risk behaviors in Black MSMW.

Design

From 2007–2011, we enrolled 437 Black MSMW into a parallel randomized control trial that compared MAALES to the control condition, a single, individualized HIV risk-reduction session.

Methods

Participants completed surveys at baseline, three- and six-months post intervention. We used multiple regressions to compare risk behaviors at follow-up between the intervention and control groups while adjusting for baseline risk behaviors, time between assessments, other covariates, and clustering. We used inverse probability weighting (IPW) to adjust for loss-to-follow-up while carrying out these regressions with the 291 (76.4%) randomized participants who completed at least one follow-up.

Results

Participants were largely low-income (55% reported monthly incomes <$1000); nearly half had previously tested HIV-positive. At six months follow-up, unadjusted within-group analyses demonstrated reduced risk behaviors for the MAALES but not the control group. Adjusted results indicated significant intervention-associated reductions in the numbers of total anal or vaginal sex acts (RR=0.61; 95% CI 0.49, 0.76), unprotected sex acts with females (RR=0.50; 95% CI 0.37, 0.66), and female partners (RR=0.56; 95% CI 0.44, 0.72). Near significant reductions were observed for number of male intercourse partners.

Conclusions

The MAALES intervention was efficacious at reducing HIV risk behaviors in Black MSMW.

Keywords: HIV Infections/epidemiology/ethnology/*prevention & control, Bisexuality, Risk Reduction Behavior, Black/African American, Homosexuality, African Americans/ethnology/psychology

Introduction

Blacks experience large disparities in HIV infection across behavioral risk groups. Transmission related to men having sex with men (MSM) is a significant contributor among Black people in the United States, accounting for almost 73% of new infections among Black men [1] and an unknown number of cases among Black women whose male partners were infected through sex with men [2]. HIV prevalence and incidence are much higher among Black than White or Hispanic MSM [3]. Black MSM are also more likely than White MSM to be bisexually active or identified (men having sex with men and women (MSMW)) and less likely to disclose their same sex activities to others [4]. Despite large racial disparities in HIV risk, few randomized trials of prevention interventions tailored for Black MSM have been published [5–7].

Interventions targeting behaviorally bisexual men of any race/ethnicity are also rare. Because of their frequent lack of identification with gay communities or labels, experiences of racism, concerns with fulfilling traditional gender expectations, discreteness regarding same-sex behavior, and relationships with both men and women, many Black MSMW may not respond to interventions targeting gay-identified men [4, 8–10]. Hence, intervention experts and community leaders have called for prevention approaches for this subgroup that address these intersecting concerns and identities [8, 11, 12].

To address the needs of Black bisexual men, paradigm shifts must occur in how sexuality is conceptualized. Attempts to explore same-sex behavior and understand sexual identity development have contributed models describe sexual exploration as a process that usually begins in early adolescence progresses toward a fixed sexual identity that is consistent with sexual activities [13–15]. Such models are the basis for interventions that place gay identities and gay community affiliations as core components. An alternative approach, considers a variety of activities, such as sex with women, with men, with transgender people, or a combination at different times or in different circumstances, as potentially normative expressions of sexual fluidity [16, 17]. Some evidence supports this alternative approach, particularly in international settings and among ethnic minority populations in the U.S. [18–21].

Gay-identity developmental models describe ambivalence regarding identification as a sexual minority as an immature stage of an exploration process [19]. While empirical research has supported these models among some White sexual minorities [19, 22–24], alternative conceptualizations may better address the seemingly incongruous sexual behaviors and identities observed among many Black MSM/MSMW [4]. The concept of sexual identity fluidity and many non-Western models of gender and sexuality [25, 26] indicate that partner choice may be context-dependent and serve purposes beyond meeting sexual desires -- such as fulfillment of familial responsibilities and gender norms. These alternative views, support interventions that target specific recent behaviors, regardless of reported sexual identity.

In response to the need for MSMW-tailored interventions, we developed the Men of African American Legacy Empowering Self (MAALES), a theoretically grounded, culturally congruent intervention aimed at decreasing sexual risk behaviors in Black/African American MSMW, and tested its efficacy in collaboration with three community-based agencies in Los Angeles. The collaborating agencies were not gay identified and provided a range of services to at-risk and HIV-infected clients [27]. Here, we report on the outcomes of this trial.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial, comparing individuals who were evenly assigned to the multi-session small-group MAALES intervention and the control condition --a brief, one-time, individualized HIV education and risk-reduction session. Assessments were collected at baseline (pre-intervention) and after receiving the intervention conditions at post, 3- and 6-months to assess for self-reported changes in risk behaviors.

Intervention - MAALES

A comprehensive description of the MAALES intervention and its theoretical basis can be found in Williams et al. 2009 [27]. Briefly, the intervention was developed with the collaborating agencies and informed by community advisory board members and extensive formative research [27]. Intervention activities and objectives were guided by the Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior [28, 29], Empowerment Theory [30], and Critical Thinking and Cultural Affirmation Model -- an Afrocentric model developed by one of our community collaborators [31] and based on Social Cognitive Theory [32, 33]. To best mirror eventual intervention dissemination, many of the intervention sessions were held at the partner agencies.

MAALES’ primary risk-reduction goals were to decrease frequency of unprotected intercourse and number of intercourse partners and reduce sex while under the under the influence of drugs. Participants were also encouraged to identify and address other health-risks such as diet, smoking, or lack of exercise. This holistic approach allowed participants to make multiple connections between the influences discussed and their health behaviors, provided a comfortable starting point for sensitive discussions, and encouraged use of specific intervention tools in multiple areas of the men’s lives. The MAALES intervention involved six two-hour small-group sessions conducted over three weeks (i.e., core sessions) with booster sessions at 6 and 18 weeks post intervention. Intervention sessions were facilitated by two African American men who were knowledgeable about HIV, familiar with the population, and experienced with group facilitation. We trained the facilitators on intervention implementation, but did not require prior specialized skills or education for this role.

Utilizing a small group format, MAALES promoted behavior change for personal benefit. It addressed social influences and cultural norms to encourage health-promoting behaviors that also benefited participants’ sexual partners, families and communities. Gender and ethnicity were emphasized, with participants’ shared legacies as African American men providing a starting place for many discussions. Sessions 1 and 2 focused on past experiences and social expectations of African American men, historical discrimination and disenfranchisement, risky behaviors, HIV testing, and societal impacts on individual health and sexual-decision making. Sessions 3 and 4 focused on current health behaviors, with specific attention on developing sexual risk-reduction goals and communication and empowerment skills and identifying personal motivators for preserving health. Sessions 5 and 6 focused on overcoming challenges to risk-reduction and developing strategies for sustaining and committing to these efforts. The two-hour group booster sessions reviewed concepts and skills learned in the core curriculum and encouraged participants to share successes and challenges in applying them.

Control Condition – An HIV Education and Risk Reduction Session

The control condition involved a client-centered HIV education and risk-reduction session based on a standard HIV test counseling approach [34]. This 15–25 minute session occurred at or soon after randomization and explored the individual’s HIV/sexually transmitted disease (STD) risks, their priorities for risk reduction and discussed the importance of regular HIV testing. Participants identified 3 risk-reduction action items that they would commit to over the next month. Control assignees were also waitlisted and invited to attend MAALES sessions after their 6-month post interview; however, the post-MAALES follow-up data for those waitlisted are not reported here.

Recruitment

Following IRB approval, recruitment began August 2007 and ended May 2011 due to the funding cycle. Recruitment strategies included outreach in public venues, provider referrals, and incentivized referrals from participants. We also posted flyers and ran advertisements in buses, on bus benches, in local community publications and on Internet sites. The majority of recruitment efforts occurred in venues that attracted African American men as a group, with fewer efforts in gay-oriented venues (Ramamurthi et al. Submitted). Trained staff screened interested individuals either in the field or by phone.

To be eligible, participants had to self-identify as a Black/African American man, have been labeled male at birth, and be at least 18 years of age. Participants also had to report at least one sexual activity (mutual masturbation, oral, vaginal, anal intercourse) with a biological female and a male (or male-to-female transgender) in the past 24 months and could not have participated in an HIV-prevention program in the prior 6 months.

In order to detect moderate effect sizes (at least 0.36 standard deviations) with 80% power and a one-sided significance level of 0.05, and assuming loss-to-follow-up of 20% and clustering effects (using an intraclass correlation of 0.05, to account for clustering inherent to a group training setting, and an average cluster size of 6 subjects), we aimed to randomize at least 300 participants.

Data Collection

Assessments

Eligible individuals were scheduled for a baseline interview at the study offices of Charles Drew University (n= 299), our community collaborators (n=96), or in the field (n=42). After obtaining informed consent, participants completed the audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) baseline survey (median completion time = 88 minutes). Follow-up ACASI interviews were scheduled within two weeks following Session 6, and at three and six months following Session 6, the last core intervention session. We only analyzed behavior changes at the 3- and 6-month assessments (median completion time = 55 minutes). Participants in both study arms were offered condoms at each follow-up survey.

Instrument

The survey assessed key background characteristics (e.g., sociodemographics, incarceration history, and self-reported HIV status) and HIV/STD testing history; hypothesized mediators (e.g., HIV knowledge, condom-related norms, intentions, and self-efficacy, HIV stigma, gender role expectations, and internalized homophobia) and potential moderators (e.g., psychological distress symptoms, experiences of racism).[35] The primary outcomes were reported for the prior 90 days and included the following:

Number of male, female, and male-to-female transgender intercourse partners;

Number of episodes of any anal or vaginal intercourse, any unprotected intercourse, and any unprotected serodiscordant intercourse;

Substance use - any binge drinking (i.e., 5 or more drinks in any single day), any illicit drug use, number of days using drugs (specifically, for heroin, cocaine, poppers, club drugs, and methamphetamines – drugs that are strongly associated with elevated HIV risk), and sex while using any of these “risky drugs”.

Randomization

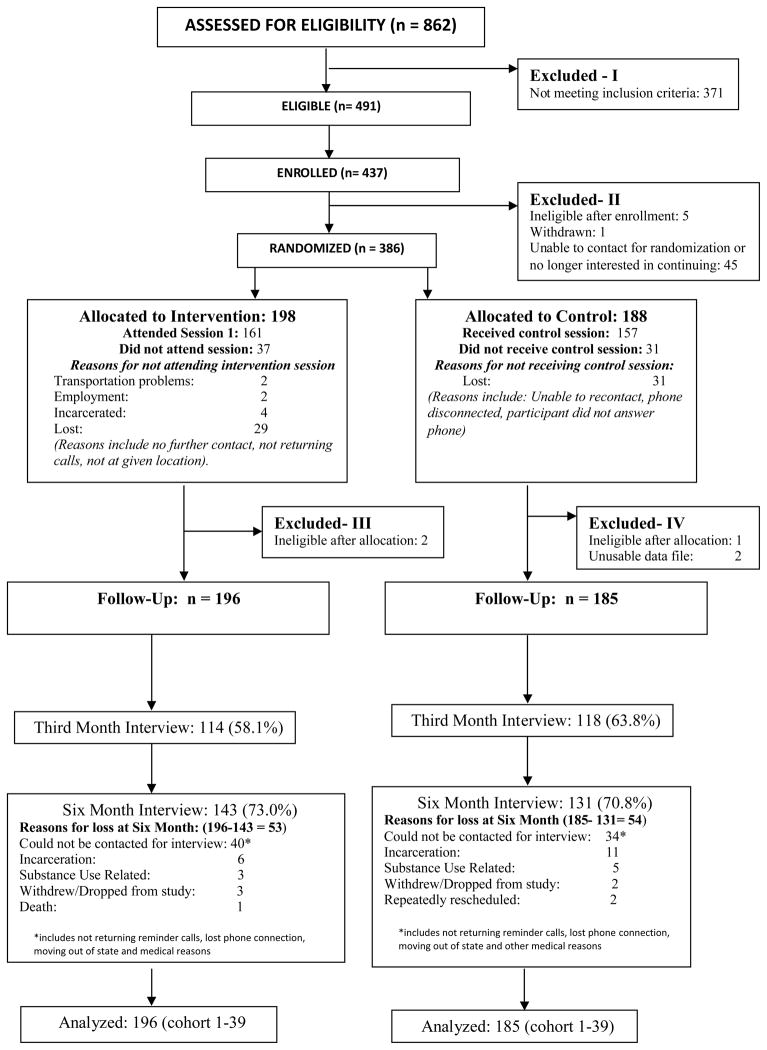

The Data Manager used a balanced-block randomization procedure with blocks of 20 to generate assignments in which 20 assigned an even number to the control and intervention groups. Each time that a sufficient number of new study participants completed the baseline, an Interviewer attempted to recontact each participant. For those wanting to continue, the Interviewer then opened a sealed envelope containing the next random assignment and informed the participant of his allocation (Figure 1). Those allocated to the intervention were invited to attend the next set of MAALES sessions. Those allocated to the control group were provided with the client-centered HIV education and risk-reduction session. We randomized individuals into a total of 39 cohorts, with a cohort representing all those who were assigned to the intervention and control conditions at a given time point. However, an individual assigned to the intervention group who was unable to attend his first assigned set of MAALES sessions could participate in a subsequent set of MAALES sessions provided it started within 90 days of his baseline. The individual’s identifying cohort was then changed accordingly.

Figure 1.

Participant CONSORT diagram of the Men of African American Legacy Empowering Self (MAALES) intervention versus the HIV education and risk reduction counseling session based on Project RESPECT

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2). Descriptive statistics were used to examine differences between the intervention and control conditions on key baseline variables. To compare intervention-associated changes at the 6 month follow-up between conditions, multiple regression models were employed. The models controlled for baseline values of the key outcome variables and independent variables that differed between those assigned to each condition at baseline (p < 0.1). We focused on the 6-month assessment because of difficulties in obtaining both follow-up interviews and a desire to assess longer-term behavior changes. When participants had completed only the 3-month assessment (n=17), that value was used for the 6-month result based on the last-value-carried-forward (LVCF) imputation paradigm. We used a zero-inflated Poisson regression model to estimate the relative reduction in frequency of unprotected intercourse and numbers of partners [36]. This model accounts for both true zeros (individuals who did not experience the event) and structural zeros (individuals who did not have the opportunity to experience the event). Risk ratios were determined from the Poisson model by exponentiating its regression coefficients. For dichotomous outcomes, we used logistic regression to estimate the relative odds of reporting any engagement in the risk behaviors.

The multiple regressions were conducted in two ways, with those participants (76.4%) who were followed up at the 3- or 6-month interviews. In the primary analysis, inverse probability weighting (IPW) was used to control for potential loss-to-follow-up bias. These weights were estimated using a logistic multiple regression model to predict loss to follow-up and retained participants were weighted by the inverse of their predicted probability of having been lost to follow-up [37]. Thus, the weights varied according to the similarity of a subject to a non-retained one, potentially making the retained group better resemble the entire population of interest. Sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics known to influence retention were used as model predictors, included age, education, income, living situation, incarceration history, self-reported HIV status, and substance use. In addition, a secondary, unweighted, complete-case analysis was conducted for those with data available at both baseline and follow-up.

The statistical models incorporated data clustering and unstructured variance-covariance models, which were based on an iterative approach requiring the determination of starting values for the initial iteration. To estimate these, a generalized model without clustering was employed. Ninety-five percent Wald confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the parameters estimates.

Results

Of the 862 individuals screened, 491 (57%) were found eligible. Of these, 437 enrolled and 386 were randomized into the intervention (n=198) and control (n=188) conditions. Three of those randomized were later determined to be ineligible and two had unusable survey data. Our analyses included the remaining 381 randomized participants, based on their random allocation. Of assigned MAALES participants, 81% completed at least one session and 58% and 73% completed their 3- and 6-month assessments, respectively. Those attending Session 1, attended a mean of 5.0 of the 6 core MAALES sessions. Of assigned control participants, 83% completed the session and 64% and 71% completed their 3- and 6-month assessments, respectively.

The mean age was 42.8 ±10.2 years, with the modal group being between 40 and 49 years of age. Although most participants had completed high school, a general equivalency diploma (GED), or higher educational attainment, their monthly incomes were low and unemployment rates were high. Over 35% had experienced housing instability in the prior 12 months and over 75% had been incarcerated in their lifetimes. Nearly half of the participants had previously tested HIV-positive, 42% had last tested HIV-negative, and 7% had never tested. The study sample’s high HIV prevalence may partially explain its low socioeconomic status.

Most participants self-identified as bisexual (60%) and nearly 60% reported having oral, vaginal, or anal sex partners in the prior 90 days who were both male and female. Although all subjects reported some type of sex with both males and females in the last two years, 20% reported only male and 11% reported only female oral, vaginal, or anal sex partners in the last 90 days. In addition, 19% reported male-to-female transgender sex partners. Few baseline differences were observed between conditions; however, controls were significantly more likely to report recent housing instability and current treatment for substance abuse (Table 1). In addition, a test of between-group differences at baseline was conducted for the outcome variables. Although one of the estimated p-values approached significance (p=0.06 for any unprotected intercourse with males or females), the other p-values were greater than 0.10.

Table 1.

Baseline comparison of intervention (n=196) and control (n=185) groups on selected sociodemographic and risk-related characteristics, among all randomized participants

| Intervention* (n=196) | Control* (n=185) | Chi Square p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | 0.9 | ||

| Less than 30 | 14.3% | 13.5% | |

| 30 to 39 | 19.4% | 17.8% | |

| 40 to 49 | 42.3% | 42.2% | |

| 50 + | 24.0% | 26.5% | |

| Level of Education | 1.0 | ||

| Less than HS | 16.3% | 15.1% | |

| High school diploma or GED | 56.1% | 56.8% | |

| Two year associates degree/certificate | 20.0% | 20.0% | |

| College Degree or higher | 7.6% | 8.0% | |

| Monthly Income | 0.2 | ||

| Less than $1000 | 57.5% | 53.3% | |

| $1000 to 1999 | 21.2% | 23.4% | |

| $2000 to 2999 | 5.2% | 10.3% | |

| $3000+ | 16.1% | 13.0% | |

| Current Employment | 0.7 | ||

| Unemployed | 44.6% | 47.0% | |

| Employed Part time | 13.8% | 12.4% | |

| Employed Full time | 5.1% | 6.0% | |

| Retired | 4.6% | 2.2% | |

| Disabled | 31.8% | 32.4% | |

| Housing Instability (past 12 months) | 33.2% | 44.3% | 0.03* |

| Substance Abuse Treatment (current) | 24.2% | 35.9% | 0.01* |

| Incarceration ever | 74.2% | 77.8% | 0.4 |

| HIV status | |||

| HIV positive | 49.0% | 47.8% | 0.8 |

| HIV negative | 40.6% | 44.6% | |

| HIV other (indeterminate, inconclusive) | 2.1% | 1.6% | |

| Never tested | 8.3% | 6.0% | |

| Sexual Orientation | 0.2 | ||

| Heterosexual | 10.7% | 17.3% | |

| Gay/Homosexual | 14.3% | 9.2% | |

| Bisexual | 60.2% | 60.5% | |

| Same Gender Loving or SGL | 2.0% | 1.2% | |

| Down Low or DL | 6.1% | 8.1% | |

| Other/none of the above | 6.6% | 3.8% | |

| Oral, Anal, Vaginal Sex Partners in prior 90 days | |||

| Male and Female Partners | 59.2% | 57.3% | 0.7 |

| Male Partners only | 22.4% | 17.8% | 0.3 |

| Female Partners only | 9.7% | 13.0.% | 0.3 |

| No Male or Female Partners | 8.7% | 10.8% | 0.5 |

| Refused to answerAny Male to Female | 0.0% | 1.1% | NA |

| Transgender Partner(s) | 15.8% | 21.6% | 0.1 |

The crude means and standard deviations for the outcomes variables at baseline and follow-up by condition are reported in Table 2. Counts and percentages are reported for dichotomous variables. Although not the principal method of analysis for this study, we evaluated within-group changes from baseline to 6 month follow-up for each condition. Statistically significant declines in sexual risk behaviors were observed for the intervention group. In contrast, these behaviors stayed the same or increased among the control group. We note that changes in overall numbers of unprotected anal sex acts with males are driven by a small portion of the sample. At baseline, only 28% and 23% of the intervention and control groups reported unprotected anal sex with male partners (including male-to-female transgender partners). This pattern, together with the skewed distribution of unprotected anal sex frequency, contributes to high standard deviations. Declines were observed in the intervention group in mean number of unprotected anal sex acts with males (p=.04). Unprotected sex with female partners was reported by 46% and 41% of the intervention and control groups at baseline and declines were again observed in the intervention group (p=.01). Finally, 24% and 16% of the intervention and control groups reported any sex under the influence of “risky” drugs at baseline; at follow-up, these percentages declined to 15% (p=.05) and 12% (p=.28), respectively.

Table 2.

Changes in reported unprotected sex acts and numbers of partners between baseline and six-month* follow-up for retained participants. Evaluation of unadjusted within-group mean differences in those assigned to the intervention (MAALES) and control groups.

| Count Outcomes | Intervention Mean (SD) (n=149) | p-value | Control Mean (SD) (n=142) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of acts (Prior 90 days) | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | ||

| Unprotected Anal Intercourse with Males (Anal) | 3.43 (10.52) | 1.43 (7.62) | .04 | 1.83 (6.21) | 1.69 (9.28) | .84 |

| Unprotected Vaginal or Anal Intercourse with Females | 5.09 (16.41) | 1.50 (4.48) | .01 | 2.72 (6.62) | 3.21 (16.46) | .76 |

| Unprotected Intercourse with Males or Females | 8.65 (22.27) | 2.95 (8.76) | <.01 | 4.66 (9.61) | 5.96 (24.79) | .91 |

| Number of Partners (Prior 90 days) | ||||||

| Males (Anal sex) | 2.49 (5.71) | 1.04 (2.54) | <.01 | 1.91 (4.08) | 1.50 (4.83) | .39 |

| Female (Vaginal sex) | 3.36 (9.42) | 1.09 (2.27) | <.01 | 2.12 (5.22) | 1.76 (7.86) | .65 |

| Dichotomous Outcomes In the last 90 days | ||||||

| Any risky** drug use | 40 (27%) | 27 (18%) | .04 | 27 (19%) | 19 (14%) | .17 |

| Any risky** drug use with sex | 34 (24%) | 22 (15%) | .05 | 22 (16%) | 16 (12%) | .29 |

Note: Paired sample t-test on group means; McNemar’s exact test for dichotomous variables.

Seventeen participants were not followed up at 6 months and their 3-month follow-up data were used instead.

Heroin, powder or crack cocaine, poppers, club drugs, or methamphetamines.

Table 3 provides results from the multiple regression models comparing the intervention to the control group at the 6-month follow-up survey controlling for baseline. The intervention group reported a 40% lower frequency of unprotected intercourse overall (IPW RR=0.61; 95% CI = 0.49, 0.67). Estimates for the intervention’s effects on sex specifically with female partners are quite robust and highly significant across analyses. For unprotected sex frequency with females, the IPW RR estimate is 0.50 (95% CI = 0.37, 0.66); the complete case RR estimate is 0.52 (95% CI = 0.38, 0.72). For number of female partners, the IPW and complete case RR estimates are 0.56 (95% CI = 0.44, 0.72) and 0.59 (95% 0.45, 0.77), respectively.

Table 3.

Comparing primary risk behavior outcomes between the intervention (MAALES) and control arms - Linear and logistic regression risk and odds ratios for six-month* post-intervention values controlling for baseline.

| Frequency Outcomes | Risk Ratios (95% CL) IPW | Risk Ratios (95% CL) Complete Case |

|---|---|---|

| Number of acts (Prior 90 days) | ||

| Unprotected Intercourse with Males or Females | 0.61 (0.49, 0.76) | 0.60 (0.47, 0.78) |

| Unprotected Vaginal or Anal Intercourse with Females | 0.50 (0.37,0.66) | 0.52 (0.38, 0.72) |

| Unprotected Anal Intercourse with Males | 0.63 (0.37, 1.09) | 0.63 (0.35, 1.12) |

| Number of Partners (Prior 90 days) | ||

| Female (Vaginal sex) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.72) | 0.59 (0.45, 0.77) |

| Male (Anal sex) | 0.75 (0.55, 1.01) | 0.80 (0.57, 1.11) |

| Dichotomous Outcomes | Odds Ratios (95% CL) IPW |

Odds Ratios (95% CL) Complete Case |

|---|---|---|

| Any, report (Prior 90 days) | ||

| Any risky** drug use with sex (among those ever gotten high) | 0.94 (0.44, 1.99) | 1.16 (0.52, 2.61) |

| Any risky** drug use with sex | 0.97 (0.46, 2.01) | 1.19 (0.54, 2.62) |

Notes: Zero-inflated Poisson regression and logistic regression models controlling for length of time between baseline and follow-up interviews and baseline values for homelessness, substance abuse treatment, and sex with transgender partners.

IPW: Inverse probability weighting

Seventeen participants were not followed up at 6 months and their 3-month follow-up data were used instead.

Heroin, powder or crack cocaine, poppers, club drugs, or methamphetamines.

Frequency of unprotected sex with males and number of male anal sex partners also showed relative reductions that were less marked. These estimates did not reach statistical significance but had p-values of less than 0.1 for the IPW regressions. For unprotected sex frequency with males, the IPW RR estimate is 0.63 (95% CI = 0.37, 1.09); the complete case RR estimate is 0.63 (95% CI = 0.35, 1.12). For the number of male partners, the IPW RR estimate is 0.75 (95% CI = 0.55, 1.01) and the complete case RR estimate is 0.80 (95% 0.57, 1.11). Finally, the odds ratios indicate that MAALES likely had no effect on the occurrence of any risky drug use or sex while high on risky drugs.

Discussion

MAALES demonstrated efficacy for reducing the frequency of unprotected sex with female partners and the numbers of female sex partners among Black MSMW. MAALES may also reduce risk behaviors with male partners; however, the low frequency of unprotected anal sex with other males made it difficult to detect intervention-related changes. Research with larger samples or higher proportions of MSMW who frequently engage in unprotected sex with males, would be needed to fully assess the intervention’s impact on this behavior. Nevertheless, our participants, similar to MSMW in a number of observational studies [38–41], were more likely to report unprotected sex with their female than with their male partners. These studies have also found lower levels of unprotected sex with male partners in MSMW than in MSMO [4, 42, 43]. Hence, an HIV intervention that reduces risky sexual activity with females may be particularly relevant to MSMW. Although MAALES focused on individual risk reduction, it framed health promotion within a broader context that also valued the well-being individuals who were intimately and communally related to participants. This paradigm, together with a conceptual framework that acknowledged sexual fluidity, may explain the findings with female partners.

The likelihood of risky drug use or sex under the influence of risky drugs did not differ between conditions. However, we did not examine intervention-associated changes in the frequency of these behaviors among users. Given that some participants may reduce rather than halt this activity, changes in frequency warrant investigation.

Limitations related to sample composition and retention may lessen generalizability of study findings. Participants tended to be over 35 years of age and to report low socioeconomic status. Also, despite our efforts to engage men of diverse sexual identities, heterosexually identified men may have been less willing than other MSMW to engage in a group intervention. Finally, even with intensive retention efforts, loss to follow-up was significant. A potential contributor to this is the high incarceration rate of Black men [44]. At least 16% of participants who were not retained were incarcerated at their 6-month follow-up interview. Bias related to loss to follow-up is minimized by the fact that retention rates differed little between study conditions and to our use of inverse proportionality weighting, the state-of-the-art method for addressing this potential bias. However, like all bias-reduction methods, the entire loss-to-follow-up bias cannot be eliminated with IPW, which depends on the available data and the validity of the logistic model. Nevertheless, the consistency between the weighted multiple regression findings, the within-group unadjusted analyses, and the unweighted complete case regressions strengthens our conclusions.

Conclusions

The demonstrated efficacy of MAALES has important implications for future HIV prevention efforts. Despite factors that may have dissuaded participation of Black MSMW in a group intervention, we reached our enrollment targets, were able to engage a large majority of the participants, and experienced high session attendance. We attributed this success to our community-partnered approach, extensive retention efforts, and to the intervention’s emphasis on gender- and ethnic-identity and acknowledgement that sexual behaviors may vary with circumstances and over the lifespan.

Study conditions were designed to closely reflect real-world implementation. Intervention facilitators were from community agencies where sessions were frequently held. Of significant benefit is that interventions administered in community agencies have the ability to provide ongoing support for positive behavior change even after formal sessions end. As the HIV field continues to move toward biomedical prevention efforts, the important role of social/behavioral interventions for engaging and supporting at-risk individuals remains [45]. Holistic HIV interventions in particular can help to endorse general prevention and health management. Such efforts may be vital for groups like Black MSMW whose concerns regarding HIV stigma, bi/homophobia, and financial hardship may complicate engagement in biomedical prevention and HIV treatment.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our collaborators, co-investigators, and study team members: Cleo Manago, Sergio Avina, Trista Bingham, Tony Wafford, Hector Myers, Tyrone Clarke, Richard Hamilton, Marvin Jones, John Kelly, Sean Lawrence, Frank Levels, Alice Meza, Shirley McIntyre, Donta Morrison, Michelle Nkoli, and Dominique Woods. Special thanks to study participants.

Funding:

This study was supported by the Drew/UCLA Project EXPORT, 2P20MD000182 from NIMHD. Additional funding for formative and pilot work was provided by the Universitywide AIDS Research Program (now the California HIV/AIDS Program), grant numbers AL04-DREW-840, AL04-UCLA-841, AL04-AMASS-842, AL04-PRCF-843, AL04-JWCH-844.

Footnotes

Clinical Trials Registration Number: NCT 01492530

Study Protocol:

The full trial protocol can be obtained by contacting Dr. Nina T. Harawa at ninaharawa@cdrewu.edu or Dr. John K. Williams at keoniwmd@aol.com.

Competing interests:

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions:

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. NT. Harawa co-led the study, wrote most of the manuscript, helped guide the analyses, and incorporated revisions into a final draft. J.K. Williams co-led the study, wrote sections of the manuscript, and provided extensive critical input into revisions. W.J. McCuller carried out the data analyses, prepared the tables, and edited drafts. H.C. Ramamurthi was the study director, prepared the CONSORT chart, and provided extensive critical input into revisions. M. Lee oversaw all of the data analyses and wrote the analysis section. Honghu Liu assisted with the power calculations and randomization procedures. M.F. Shapiro and K.C. Norris assisted with conceptualizing the manuscript and provided critical input into revisions. W.E. Cunningham assisted with conceptualizing the manuscript and provided extensive critical input into revisions throughout the editing process.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. (2011) 2009;21 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan A, Robbins RN, Ruiz MS, O’Neill D. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention in prison among African Americans, Hispanics, and Caucasians. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33:154–177. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV prevalence, unrecognized Infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men --- Five U.S. cities, June 2004--April 2005. Monthly Morbidity & Mortality Report. 2005;54:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millett G, Malebranche D, Mason B, Spikes P. Focusing “down low”: bisexual black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:52S–59S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Operario D, Smith CD, Arnold E, Kegeles S. The Bruthas Project: Evaluation of a Community-Based HIV Prevention Intervention for African American Men who have sex with men and women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22:37–48. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson JL, Coates TJ, Catania J, Hauck WW, Acree M, Daigle D, et al. Evaluation of an HIV risk reduction intervention among African-American homosexual and bisexual men. AIDS. 1996;10:319–325. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199603000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilton L, Herbst JH, Coury-Doniger P, Painter TM, English G, Alvarez ME, et al. Efficacy of an HIV/STI prevention intervention for black men who have sex with men: findings from the Many Men, Many Voices (3MV) project. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:532–544. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mays VM, Cochran SD, Zamudio A. HIV prevention research: Are we meeting the needs of African American men who have sex with men? Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:78–105. doi: 10.1177/0095798403260265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myrick R. In the Life: Culture-specific HIV communication programs designed for African American men who have sex with men. J Sex Research. 1999;36:159–170. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Resell J, Peterson J, Asuan-O’Brien A. Psychosocial issues among gay- and non-gay-identifying HIV-seropositive African American and Latino MSM. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10:268–286. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler DP. Exploring HIV prevention needs for nongay-identified black and African American men who have sex with men: a qualitative exploration. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:S11–16. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000216021.76170.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malebranche DJ. Bisexually active Black men in the United States and HIV: acknowledging more than the “Down Low”. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:810–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troiden RR. The formation of homosexual identities. J Homosex. 1989;17:43–73. doi: 10.1300/J082v17n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: a theoretical model. J Homosex. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman E. Developmental stages of the coming out process. In: Gonsiorek J, editor. Homosexuality and Psychotherapy: A practitioners’ Handbook of Affirmative Models. New York: Hawthorn Press; 1982. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vrangalova Z, Savin-Williams RC. Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:85–101. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sell RL. Defining and measuring sexual orientation: a review. Arch Sex Behav. 1997;26:643–658. doi: 10.1023/a:1024528427013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubé EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:1389–1398. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubé EM. The role of sexual behavior in the identification process of gay and bisexual males. J Sex Res. 2000;37:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ream GL, Savin-Williams RC. Reciprocal associations between adolescent sexual activity and quality of youth-parent interactions. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:171–179. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moradi B, Mohr JJ. Counseling psychology research on sexual (orientation) minority issues: Conceptual and methodological challenges and opportunities. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56:5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Augelli AR. Gay men in college: Identity processes and adaptations. J Coll Stud Dev. 1991;32:140–146. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savin-Williams RC, Lenhart RE. AIDS prevention among gay and lesbian youth: Psychosocial stress and health care intervention guidelines. In: Ostrow DC, editor. Behavioral Aspects of AIDS. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savin-Williams RC. The disclosure to families of same-sex attractions by lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. J Res Adolesc. 1998;8:49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinnish KK, Strassberg DS, Turner CW. Sex differences in the flexibility of sexual orientation: A multidimensional retrospective assessment. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-1795-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roscoe W, Murray SO. Boy-Wives and Female-Husbands: Studies in African Homosexualities. 1. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams JK, Ramamurthi HC, Manago C, Harawa NT. Learning from successful interventions: A culturally congruent HIV risk-reduction intervention for African American men who have sex with men and women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1008–1012. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Bechman J, editors. Action Control from Cognition to Behaviour. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes Special Issue: Theories of cognitive self-regulation. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freire P, Ramos MB, Macedo D. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 2000. p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manago C. A Critical Thinking and Cultural Affirmation (CTCA) Approach to HIV Prevention and Risk Reduction, Consciousness, and Practice for African American Males at HIV Sexual Risk. Los Angeles: The AmASSI Center; 1996. pp. 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. (AIDS prevention and mental health) New York, NY, US: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC. Project RESPECT Brief Counseling Intervention Manual. Atlanta: CDC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bingham T, Harawa N, Williams J. Gender Role Conflict Among African American Men Who Have Sex With Men and Women: Associations With Mental Health and Sexual Risk and Disclosure Behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300855. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert D. Zero-Inflated Poisson Regression Models with an Application to Defects in Manufacturing. Technometrics. 1992;34:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740. Epub 2011 Jan 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorbach PM, Murphy R, Weiss RE, Hucks-Ortiz C, Shoptaw S. Bridging sexual boundaries: men who have sex with men and women in a street-based sample in Los Angeles. J Urban Health. 2009;86 (Suppl 1):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH, McFarland W, Shehan DA, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. Young Men’s Survey Study Group. JAMA. 2000;284:198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spikes PS, Purcell DW, Williams KM, Chen Y, Ding H, Sullivan PS. Sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive black men who have sex with women, with men, or with men and women: implications for intervention development. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1072–1078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Cranston K, Isenberg D, Bright D, Daffin G, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and partner characteristics of black MSM in Massachusetts at increased risk for HIV infection and transmission. J Urban Health. 2009;86:602–623. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9363-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latkin C, Yang C, Tobin K, Penniman T, Patterson J, Spikes P. Differences in the social networks of African American men who have sex with men only and those who have sex with men and women. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:e18–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stokes JP, Vanable P, McKirnan DJ. Comparing gay and bisexual men on sexual behavior, condom use, and psychosocial variables related to HIV/AIDS. Arch Sex Behav. 1997;26:383–397. doi: 10.1023/a:1024539301997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonczar TP, Beck AJ. Lifetime likelihood of going to state or federal prison. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adam BD. Epistemic fault lines in biomedical and social approaches to HIV prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14 (Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]