Abstract

The association between marital discord and depression is well established. Marital discord is hypothesized to be a stressful life event that would evoke one’s efforts to cope with it. In an effort to further understand the nature of this association, the current study investigated coping as a mediating variable between marital dissatisfaction and depression and between marital instability and depression. Both marital dissatisfaction and instability, reflecting orthogonal dimensions of marital discord, were included in the model examined to elucidate a more complete picture of marital functioning. Structural Equation Modeling analyses revealed that coping mediated the association between marital instability and depression, but not marital dissatisfaction and depression, suggesting that coping traditionally considered adaptive for individuals in the context of controllable stressors may not be adaptive in the context of couple relationship instability. The findings also have implications for interventions focusing on decreasing maladaptive coping strategies in couples presenting for marital therapy or depression in addition to efforts directed at improving marital quality.

Keywords: marital satisfaction, marital discord, marital quality, coping, depression

The association between marital discord and depression has long been recognized by therapists and researchers alike, with marital discord predicting depression longitudinally in the absence of previous depression (Christian-Herman, O’Leary, & Avery-Leaf, 2001). Depression in the marital context is important for researchers and therapists to understand so that effective interventions can be developed both to relieve the duress of the couple and to meet the demand for such services. It is quite common for couples seeking marital therapy to be mildly to moderately depressed (Dehle & Weiss, 1998), and individuals experiencing subclinical levels of depression actually use more medical services than clinically depressed individuals (O’Leary, Christian, & Mendell, 1994).

Discordant Marriage as a Risk for Depression

Although it appears that depression may have some impact on marital functioning through venues such as spousal burden (Benazon & Coyne, 2000), greater evidence suggests that marital functioning plays a role in the development of depression (Christian-Herman et al., 2001; Whisman & Kaiser, 2008; Whitton & Whisman, 2010). Several large epidemiology studies suggest that both husbands and wives in discordant marriages are 10 to 25 times more likely to develop depression (O’Leary et al., 1994; Weissman, 1987). Mood disorders are also the only psychiatric disorders that are uniquely and significantly associated with marital discord for both men and women (Whisman, 1999).

There is also evidence that depression is resistant to treatment in cases where marital discord remains high. Specifically, 50% of a sample of moderately depressed women participating in a randomized clinical trial of antidepressant medication reported that their marital disputes were a prominent and contributory feature of their current clinical picture (Rounsaville, Weissman, Prusoff, & Herceg-Baron, 1979). Those who saw improvements in their marital problems also saw significant improvements in their depressive symptoms. Women, who initially experienced an improvement in their depressive symptoms with medication, but not in their marital problems, experienced a return of their depressive symptoms despite the continued use of antidepressants. It appears that the repeated difficult discussions of discordant couples contribute to the maintenance of depressive symptoms (O’Leary, Riso, & Beach, 1990; Whisman, Weinstock, & Ubelacker, 2002) and explain why marital discord typically precedes the onset of depressive symptoms (Hollist, Miller, Falceto, & Fernandes, 2007; Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999; Whisman & Bruce, 1999). When considering the association between marital discord and depression, it is important to acknowledge that not all spouses experiencing marital discord become depressed, and that the depressive symptoms of those who do become depressed can be disproportionate to the degree of their marital discord (Christian, O’Leary, & Vivian, 1994; Rounsaville et al., 1979). Because of this, one must consider the role of variables that may reflect vulnerability or resilience and act as mechanisms of effect.

Marital Instability

A limitation of the above-described studies is their failure to measure the instability of the marriages. This is an important oversight because immunological studies indicate that marital disruption is more stressful than marital dissatisfaction (see Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1987). Thus, the inclusion of marital instability may be particularly important to understanding the association between marital distress, coping, and mental health outcomes. Longitudinal studies of marital satisfaction and stability have found that marriages tend to become less satisfied, but more stable with time (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Although marital dissatisfaction has larger effects on marital instability than other variables examined, its association with marital instability is not large. These findings indicate that while dissatisfaction and instability are related outcomes, they are not interchangeable and should be examined separately in studies of marital quality.

Coping Style

A person’s coping style is represented by the typical behavioral and cognitive efforts one makes in attempting to tolerate, master or reduce internal and external demands and the conflicts between demands. Coping is conceptualized as being a complex multidimensional process that is sensitive to contextual factors as well as individual appraisals of the stress and available resources (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). Coping styles have been most prevalently divided into two broad categories: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Attempts to alter the environment–person association in a stressful situation are typically viewed as problem-focused coping, are considered adaptive, and have been associated with positive outcomes (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). Attempts to regulate negative emotions in a stressful situation are viewed as emotion-focused coping, have largely been considered maladaptive, and have been consistently associated with the development of clinical depression in the context of negative life events (Carver & Sheier, 1994; Folkman & Lazarus, 1980, 1986; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993). Entering marital therapy to address marital problems is an example of problem-focused coping, whereas venting or drinking alcohol to “relax” and cope with the tension associated with marital discord are examples of emotion-focused coping.

There is also evidence that the prevalence of coping strategies vary in relation to the phases of a stressful encounter and are associated with an appraisal of the controllability of the stressor. Problem-focused coping appears to be used and most adaptive when stressors are considered controllable (Christensen, Benotsch, Wiebe, & Lawton, 1995; Conway & Terry, 1992), such as when anticipating a stressful event (Lazarus & Folkam, 1985). Emotion-focused coping appears prevalent after the outcome of a stressful event when it was clear that one’s actions could not affect the outcome. A combination of emotion-focused and problem-focused coping appears to be used after a stressful event, but before receiving information about the outcome when there may be ambiguity about the controllability of the stressor.

Coping as a Mediating Variable

When considering the role of coping in the association between marital discord and depression, it is important to determine whether it is a mediating or a moderating variable. Moderating variables are antecedent conditions, such as gender or temperament, which interact with other variables to create an outcome. Mediating variables are created in a situation and change the association between antecedent variables and the outcome (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Although researchers have looked at some potential moderators of the association between marital discord and depression, such as gender and spousal warmth (Davila, Karney, Hall, & Bradbury, 2003; Proulx, Buehler, & Helms, 2009), no published literature has investigated the role that coping may play in this association. In an attempt to determine whether coping was a mediating or moderating variable in the association between stress and emotion, Folkman and Lazarus (1988b) interviewed 331 participants once a month for 6 months. The participants were asked to reconstruct a stressful or emotional encounter that they had experienced during the week preceding the interview. The authors found that coping mediated, rather than moderated, the impact of stress on emotion because planful problem-solving and positive reappraisal were associated with an improved emotional state, whereas confrontive coping (“getting it off one’s chest”) and distancing or avoidance were associated with a worsened emotional state. Thus, coping is hypothesized to mediate the association between marital discord and symptoms of depression in the current study.

The Current Study

Marital discord is a stressful negative life event, and although discordant couples are at an increased risk for depression, not all discordant couples experience corresponding levels of depressive symptoms (Christian et al., 1994; Ilfeld, 1980; Rounsaville et al., 1979). The marital discord theoretical model of depression states that marital discord is a stressful negative life event that increases the risk of depression because of reduced support and effective coping (Beach, Sandeen, & O’Leary, 1990). Although this theory suggests that coping partially mediates the association between marital discord and depression, this potential mediating association remains to be examined. In an effort to understand the association between marital discord and depression, investigations have typically pursued an understanding of the direct influence of marital discord on depression. Coping is considered a good potential mediator because, as discussed, coping styles have been found to mediate the association between stressful events overall and emotional responses (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988a). In an effort to synthesize these literatures and further understand the association between marital discord and depression, this study investigated coping as a mediator of the association between marital quality and depression. Specifically, emotion-focused coping was expected to mediate an association between marital discord (reflected by marital dissatisfaction and instability) and depression. Marital dissatisfaction and marital instability were each measured because they are considered orthogonal dimensions of marriage (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Marriages can be considered to be a balance of attractions to the relationship and barriers to leaving it. Because of this balance, marriages can, therefore, be satisfied and stable, dissatisfied and stable, satisfied and unstable, and dissatisfied and unstable and vary in these qualities over the life cycle.

Method

Participants

Participants were 80 legally married individuals. Fifty participants were recruited from undergraduate psychology courses at a large state university in New Mexico (38 females and 12 males, M age = 29.76 years, SD = 8.29, range = 30 years). An additional 30 participants were new parents participating in the Bringing the Baby Home (BBH) project, recruited from birth preparation classes in Seattle, Washington (13 females and 17 males from different marriages, M age = 35.80 years, SD = 4.75, range = 19 years). Overall, participants across both subsamples reflect marital relationships in their early stages and within the first decade of marriage (NM sample, M = 5.39 years married, SD = 6.09, range = 26.75 years; WA sample, M = 6.49 years married, SD = 2.09, range = 9.25 years). The average marital satisfaction score on the Marital Adjustment Test (M = 112.01, SD = 25.58) reflects marital satisfaction typically expected for couples during the early stages of marriage (Shapiro, Gottman, & Carrere, 2000; Shapiro & Gottman, 2004). There were no significant differences in marital satisfaction scores between the NM sample (M = 112, SD = 27.49) and the WA sample (M = 112, SD = 22.47; t(78) = −0.02, p = .99), nor were there significant differences in marital instability scores (NM, M = 1.40, SD = 2.50; WA, M = .60, SD = 1.22; t(78) = 1.64, p = .11) or depression scores (NM, M = 8.92, SD = 7.13; WA, M = 7.75, SD = 7.75; t(57) = 0.72, p = .47). Sixty-five percent of the participants were Caucasian, 20% were Hispanic or Latino, 6.3% were Asian, 5% were Native American and 2.5% were African American. The participants were also generally well educated, with 97.5% reporting at least some college and only 2.5% reporting only a high school education. Participants recruited from psychology courses received one hour of research credit, and couples participating in the BBH project were reimbursed $10 an hour for their time in the study. Volunteers were treated in accordance with APA ethical principles (American Psychological Association, 2002), and all procedures were approved by human subjects review boards at the respective institutions in New Mexico and Washington.

Materials

Marital satisfaction

Marital satisfaction was assessed using the Locke–Wallace Marital Adjustment Test (MAT; Locke & Wallace, 1959). The MAT is a widely used and validated 15-item self-report measure that assesses global relationship satisfaction and effectively discriminates between distressed and nondistressed couples. The MAT correlates highly with measures of sexual satisfaction, communication, and positive feelings toward one’s spouse (Arias & O’Leary, 1985), and is sensitive to treatment changes (Margolin & Weiss, 1978). The Cronbach’s alpha for the MAT in this sample was .78, reflecting acceptable internal reliability.

Marital instability

Marital instability was assessed with the Weiss–Cerreto Marital Status Inventory (MSI; Weiss & Cerreto, 1980). The MSI is a 14-item Guttman-like intensity scale that measures the likelihood of marital dissolution. The MSI was designed on the assumption that a marriage dissolves in a series of sequential discrete acts. Marital instability was assessed in conjunction with marital satisfaction as an important facet of the overall cohesion of the couple. Cronbach’s alpha for the MSI in this sample was .85.

Coping

Coping skills and dispositions were assessed using the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997). The Brief COPE is a 28-item scale with 14 subscales that are designed to measure both broad coping dispositions and coping tendencies in specific situations. The Brief COPE is scored on a Likert-type scale of 1 (“I haven’t been doing this at all”) to 4 (“I have been doing this a lot”), with higher scores reflecting more engagement in a coping behavior. For the purposes of the current study and as encouraged by Carver (1997), the 14 subscales of the Brief COPE were divided into two broad categories reflecting general problem-focused and emotion-focused coping tendencies. The items were also subsequently entered into a principal components analysis (PCA) to create one composite coping factor, which is examined in an alternate model. The Cronbach’s alpha for the Brief COPE in this sample was .87.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II is a 21-item measure that assesses the severity of depressive symptoms, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha for the BDI-II in this sample was .90.

Setting and Procedure

Participants recruited from undergraduate courses were assessed in groups of 1 to 10 in classrooms in the Department of Psychology at the University of New Mexico. Couples participating in the BBH project completed the above questionnaires as part of an assessment when their infants were 2 years old. Data from the BBH project included measures from both spouses. To resolve the problem of nonindependence in the scores assessed (Kenny & Judd, 1986), data from one spouse of each couple were randomly selected and included in the analyses of the current study. This procedure resulted in data from 13 husbands and 13 wives from different marriages being selected for data analysis. There were four couples where the wife had missing data and the husband’s data were complete, so in these cases the husband’s data were selected for analysis.

Results

Data Analysis

A structural equation modeling (SEM) procedure was used to test two alternate models describing the association between marital satisfaction, marital instability, coping style and depression. SEM is a statistical method used to estimate the goodness of fit of a hypothesized model to observed associations among variables and is primarily used for nonexperimental research where neither the independent nor dependent variable is manipulated (Bullock, Harlow, & Mulaik, 1994). The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 19.0) and AMOS (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999) statistical programs were used to analyze the data. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of the measured variables in the initial model. Although the covariance matrix was used for the SEM analysis, the correlation matrix (see Table 2) is presented for the purposes of interpretation.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Measured Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Marital satisfaction | 112.01 | 25.58 |

| Marital instability | 1.10 | 2.14 |

| Problem-focused coping | 29.99 | 7.41 |

| Emotion-focused coping | 22.78 | 6.37 |

| Depression symptoms | 8.45 | 7.35 |

Note. For marital instability, the higher the score the more unstable the marriage.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of the Measured Variables

| Instability | Satisfaction | E-F coping | P-F coping | Coping | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instability | — | |||||

| Satisfaction | −.66** | — | ||||

| E-F coping | .16 | −.02 | — | |||

| P-F coping | .30** | −.03 | .69** | — | ||

| Coping | .26* | .16 | .91** | .91** | — | |

| Depression | .32** | −.37** | .42** | .23* | .35** | — |

Note. E-F coping = emotion-focused coping; P-F coping = problem-focused coping; Coping = single-factor coping.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Model 1

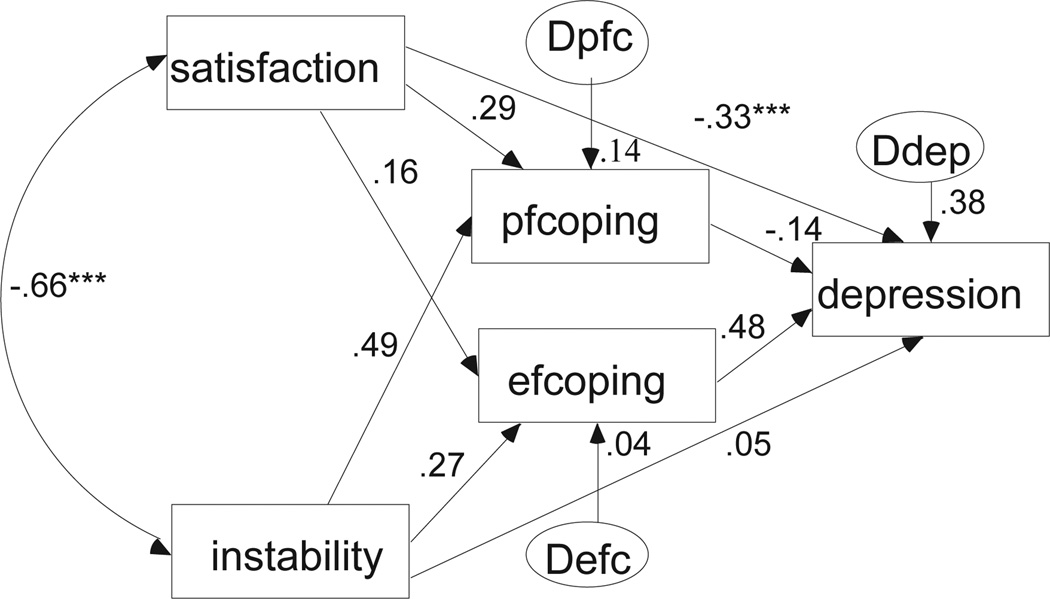

The first model investigated problem-focused and emotion-focused coping behaviors as mediators in the associations between marital satisfaction and depression and marital instability and depression (see Figure 1). The overall fit of Model 1 was evaluated using several goodness-of-fit indices. These are as follows: χ2 = 49.03, p = .0001, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .63, standardized root mean residual (SRMR) = .18, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .97. In the present study, 90% confidence intervals are presented. The significance level for the χ2 is <.05, which indicates that there is a significant difference between the hypothesized and the observed covariance matrices, and that the hypothesized theoretical model did not fit the data well (Hoyle & Panter, 1995). CFI is a nonnormed incremental fit index that compensates for the effect of model complexity. The CFI of .63 also indicates a poor fit of this model because values <.95 are generally considered inadequate (Hu & Bentler, 1999). SRMR and RMSEA are absolute fit indices. The SRMR values <.08 and RMSEA values <.08 indicate adequate fit while SRMR and RMSEA values <.05 indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). As such, both of these indices also indicate a poor fit of this model.

Figure 1.

Model 1. Satisfaction, instability, problem-focused coping (pfcoping), emotion-focused coping (efcoping) and depression are all regarded as observed variables. Dpfc, Defc, Ddep refer to error terms.

***p < .001.

Model 2

Given the poor fit of Model 1 and the high correlation between the emotion-focused and problem-focused coping subscales (r = .69, p < .01) that suggested participants were using a degree of both of these strategies, a composite Coping variable was examined as the mediator in Model 2. To obtain this composite Coping variable, the 28 items of the Brief COPE were subjected to PCA using SPSS Version 19. Before performing the PCA, the suitability of the data for factor analysis was assessed. Inspection of the correlation matrix revealed the presence of many coefficients of .30 and above. The Kaister–Meyer–Oklin value was .63, exceeding the recommended value of .60 (Kaiser, 1970, 1974), and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Bartlett, 1954) reached statistical significance, supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix. PCA revealed the presence of one component, named Coping, with an eigenvalue exceeding one, explaining 24.38% of the variance. Higher scores on the Coping variable reflect increased coping efforts for both emotion-focused and problem-focused strategies (see Table 3 for factor loadings).

Table 3.

Loadings of Items on Single Coping Component

| Coping item | Component loading |

|---|---|

| 1. Come up with strategy about what to do. | .66 |

| 2. Saying things to let unpleasant feelings escape. | .63 |

| 3. Trying to get help and advice from others. | .61 |

| 4. Doing something to think about it less. | .60 |

| 5. Expressing my negative feelings. | .57 |

| 6. Saying, “This isn’t real.” | .57 |

| 7. Accepting the reality of the fact. | .55 |

| 8. Getting comfort and understanding from someone. | .55 |

| 9. Refusing to believe that it has happened. | .53 |

| 10. Using alcohol or drugs to feel better. | .53 |

| 11. Learning to live with it. | .52 |

| 12. Concentrating efforts on doing something. | .52 |

| 13. Taking action to make situation better. | .51 |

| 14. Work/other activities to take mind off things. | .51 |

| 15. Getting emotional support from others. | .50 |

| 16. Looking for something good in what has happened. | .50 |

| 17. Criticizing myself. | .47 |

| 18. Blaming myself. | .47 |

| 19. Using alcohol or drugs to get through. | .47 |

| 20. Trying to see it in a different light. | .44 |

| 21. Giving up attempts to cope. | .40 |

| 22. Giving up trying to deal with it. | .35 |

| 23. Trying to find comfort in religion/spiritual beliefs. | .34 |

Note. Items in bold reflect emotion-focused coping.

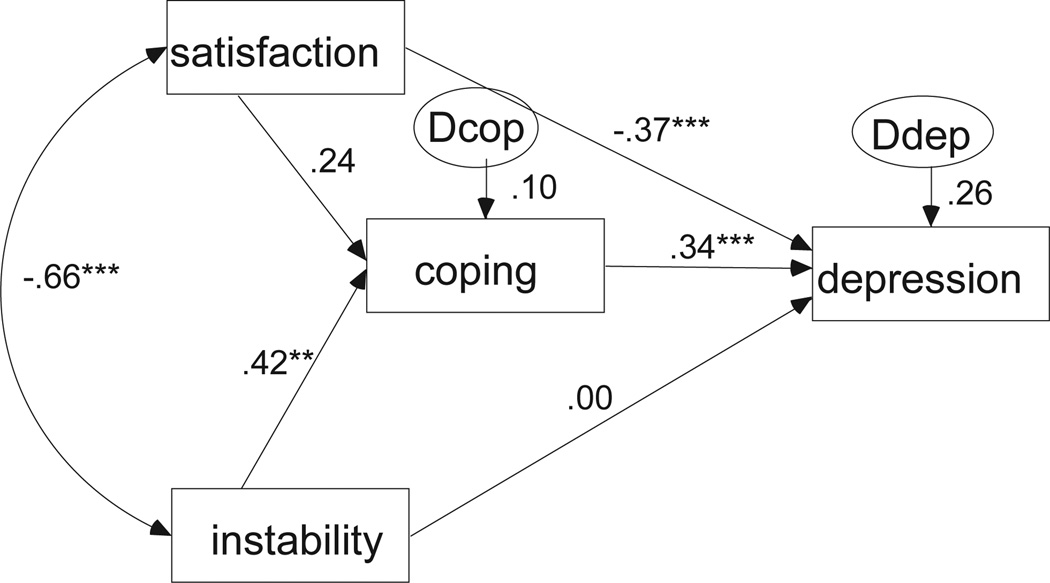

To obtain the degrees of freedom necessary to fit a model, it is common practice to fix a nonsignificant path to zero (Kline, 2005). In this model, the nonsignificant path between Instability and Depression was fixed to zero to obtain the necessary degrees of freedom to fit a model. Model 2 is presented in Figure 2. For Model 2, the fit indices were as follows: χ2 = 0.041, p = .84, ns; CFI = 1.000; SRMR = .0044, and RMSEA = .173. The significance level for χ2 is >0.05, indicating a nonsignificant difference between the observed and the hypothesized covariance matrices. Such a finding indicates that the hypothesized theoretical model fits the data adequately. Values indicating adequate fit were also found using CFI, which was 1.00 in the case of Model 2. Although the typical range for the CFI lies between 0 and 1, values >.95 indicate a very good fit (Kline, 2005). Values <.08 are considered to indicate good fit using SRMR (Hu & Bentler, 1999) and a good fit is, likewise, indicated by the SRMR with a value of .004. Although the RMSEA value of .17 is higher than the .08 recommended, it has been noted that RMSEA can be artificially large when the degrees of freedom are small, as in the case of the present study (Kenny, 2011), and Kenny, Kaniskan and McCoach (2011) have argued that RMSEA should not even be computed in cases where the degrees of freedom are small. For conducting SEM, the sample of the current study is relatively small. Regardless, given the highly nonsignificant χ2 and the indication of good fit by the other goodness of fit indices, we believe this second model fits the data adequately.

Figure 2.

Model 2. Satisfaction, instability, coping and depression are all regarded as observed variables. Dcop and Ddep refer to error terms.

**p < .01, ***p < .001.

Interpretation of the Paths in Model 2

There was a significant negative correlation between Satisfaction and Depression (r = −.37, p < .001). The association between Satisfaction and Coping was not, however, significantly correlated. Taken together, these findings indicate a large significant direct association between low marital satisfaction and symptoms of depression, with no mediation by the Coping variable. The correlations between both Instability and Coping (r = .42, p < .01), and Coping and Depression (r = .34, p < .001) were statistically significant, but the association between Instability and Depression was not significantly correlated. This combination of findings indicates that the association between marital instability and depressive symptoms is mediated by Coping. There was also a significant negative correlation (r = −.66, p < .001) between Satisfaction and Instability.

Discussion

The marital discord model of depression suggests that coping partially mediates the association between marital discord and depression. The current study examined this mediation model using SEM. Coping was considered a good potential mediator because coping styles have been found to mediate the association between stressful events overall and emotional responses (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988a). In an effort to synthesize these literatures and further understand the association between marital discord and depression, the current study investigated coping as a mediator of the association between marital discord and marital instability. Because marital dissatisfaction and marital instability are considered orthogonal dimensions of marital quality (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), we included measures of both of these aspects of marital quality in the two models tested.

The current investigation examined two models reflecting two different ways coping could mediate the association between marital discord and depression. One model examined emotion-focused coping and problem-focused coping as two separate mediators, whereas the second model included a single composite Coping factor as the mediator between marital distress and depressive symptomatology. The model with the single composite Coping factor fit the data well in contrast to the initially hypothesized model that examined emotion-focused and problem-focused coping separately. This finding was curious, given that emotion-focused coping has been typically associated with depression in the literature, and problem-focused coping has traditionally been conceptualized as adaptive, and has been associated with positive outcomes (see Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). The emotion-focused and problem-focused coping variables were, however, highly and significantly correlated, and the composite of Coping factor includes both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping items with high loadings. Thus, it is not the case that the factor reflects mostly emotion-focused coping with minimal problem-focused coping, but rather a combination of both types of coping.

The combination of emotion-focused and problem-focused coping may be due to the individual’s appraisal of the stressor in the relationship context and appears to be consistent with Lazarus and Folkman (1985) where both emotion-focused and problem-focused coping are seen in situations where the controllability of a stressor may seem somewhat ambiguous, such as after a stressor has occurred but before the outcome is clear. Marital instability may be a similarly ambiguous stressor because an individual’s efforts may or may not have an impact on the stability of the relationship, which depends on the efforts and decisions of two people.

It is also possible that coping styles that are adaptive for the individual in many situations may not be adaptive in the context of couple relationships. For example, a strategy developed by one person may or may not be appropriate in a marriage where two people need to negotiate the course of the relationship. Similarly, seeking social support from someone outside the relationship regarding difficulty within the relationship, may result in friends or family members siding with an individual against their spouse, and could lead to further relationship instability rather than positive feelings long term. This explanation is consistent with concerns raised by O’Brien and DeLongis (1997) in that coping strategies that are beneficial to an individual may not be beneficial to their spouse, and with findings that one spouse’s stress can influence their partner’s distress (Berghuis & Stanton, 2002). Although coping was conceptualized at the individual level in the current research because of the outcome of interest being the individual’s depression, it is possible that a measure of communal coping may be more appropriate for tapping into adaptive coping in the context of couple relationships than a measure of individual coping, such as the one examined by Wells, Hobfoll, and Lavin (1997) that emphasizes a cooperative response to stressful life events.

The results of this study suggest that the way one copes with stressful events mediates the association between marital instability and depression, but not the association between marital satisfaction and depression. Our finding, that links coping and symptoms of depression, is consistent with the coping literature, which suggests that people who use certain strategies are at greater risk for developing depression (Beach, Arias, & O’Leary, 1986; Beach & O’Leary, 1993; O’Leary et al., 1994). There was also a significant direct association between low marital satisfaction and depression that is consistent with existing research indicating associations between marital discord and depression (see Whisman & Kaiser, 2008). This could indicate that no mediation is taking place, or the need to examine further potential mediators.

It was somewhat surprising that coping did not mediate the association between marital satisfaction and depression, given past research indicating associations between marital discord and coping (Christian et al., 1994; Kessler & Essex, 1982), and associations between depression, marital quality, and coping-related variables such as conflict management and problem solving (Coyne, Thompson, & Palmer, 2002; Mitchell, Cronkite, & Moos, 1983). None of these studies measured marital instability, however, and none specifically examined coping processes as a mediator of the association between marital discord and depression. Given that the present study also found a significant negative association between marital instability and marital satisfaction, it is possible that previous research indicating associations between marital quality and coping-related processes actually reflected an association between marital instability and coping that was obscured. It is also possible that the expected significant association was not found because of the present sample having a fairly high average marital satisfaction in which active coping may not be elicited as consistently as in clinical samples where greater marital and psychological distress are more prevalent. Another important consideration is that stability is a characteristic of the couple, whereas marital satisfaction is an individual experience referring to how an individual evaluates his or her marriage (Orathinkal & Vansteenwegen, 2006). Future research with clinical samples will be important for further dissociating these processes.

Although a thorough discussion of associations between developmental stage, marital discord, coping, and depression is beyond the scope of the current research, it is important to note that participants were largely in the early stage of marital relationships (within the first 10 years of marriage). This early formative period of marriages has been associated with changes in marital attachment (Davila, Karney, & Bradbury, 1999). Additionally, the transition to parenthood many couples undergo during this period has been associated with changes in marital satisfaction (Shapiro et al., 2000), intensity of areas of disagreement (Storaasli & Markman, 1990), and negativity during conflict (Shapiro & Gottman, 2005). Thus, the participants examined were likely to be experiencing changes in their relationships around the time they were surveyed. Furthermore, because marriages tend to become more stable over time (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), marital instability and related stresses may have been particularly prevalent in the sample of early marriage participants examined compared with those with more mature marriages.

The findings from the present study also suggest that there may be two different paths to depression for married people, a direct path from marital dissatisfaction to depression and a mediated path from marital instability through coping to depression. This is an important distinction because it may address questions regarding why people can experience depressive symptoms that are more severe than their level of marital discord. Thus far, theorists have inferred that it is because these individuals were maladaptively coping with the stress of being in an unhappy marriage (Beach et al., 1990), but our findings suggest that the path to depression may be more complex and that individuals may be responding to the level of instability in the relationship.

Because our model suggests that coping does not mediate the association between marital dissatisfaction and depression, future research should also investigate other potential mediators or moderates of this association. Other variables that should be investigated as mediators and moderators include relationship-level variables, such as commitment to the relationship; and individual-level variables, such as personality and dispositional characteristics. Future studies including these variables are likely to increase our understanding of the contextual and systemic functioning of distressed couples.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered in evaluating the generalizability of these findings. The first limitation is the study’s correlational nature and sample composition. The variables examined were collected from participants at a single time point in this non-experimental study. Thus, neither causality nor directionality can be inferred from the current data; however, the models do reflect patterns of relationships discussed in the existing literature. Longitudinal research is recommended to better examine the directionality of associations, and random clinical trials research testing interventions focused on helping people to reduce their maladaptive coping in the context of relationship discord would be needed to test for a causal association between coping and depression in the context of marital discord. Also, although a small sample size is typically a limitation for conducting SEM, the models were fairly straightforward with limited parameters and did not limit the ability to fit a model to our data.

In addition, because a convenience sample was examined, individuals who volunteered to participate in the study may have been more interested in their marriages than people who chose not to participate. Overall, the participants reported being fairly satisfied and secure in their marriages, and thus, any associations between marital quality, coping, and depression evident only in cases of severe marital distress would not have been detected in the current research. Future research examining a large probability sample of married individuals is recommended to achieve a greater distribution of values on all of these measures as well as greater statistical power. Lastly, the age range of the sample was somewhat restricted, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other age groups.

Conclusion and Implications for Treatment

Couples seeking therapy for relationship problems are undoubtedly doing so because they are unhappy with the quality of their marriage and, as such, are often experiencing depressive symptomatology. Similarly, individuals seeking therapy because of depression may be experiencing relationship discord as well. The results of the present study suggest that the association between marital quality and depression is not as simple or direct as once thought. Furthermore, therapists and theorists may benefit from considering that adaptive coping may be different in a relationship context than in an individual context. Consistent with a communal coping perspective, this may involve helping couples develop the belief that a joint effort is needed, advantageous or useful; helping couples communicate about the situation in adaptive nonblaming ways; and helping the couple engage in cooperative action to work toward solving the problem of their marital discord (Lewis et al., 2006). This includes encouraging the couple to identify the marital discord as “our” problem and “our” responsibility rather than a problem that belongs to “you” or “me.”

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the Talaris Research Institute, the Kirlin Foundation, and the Apex Foundation.

Contributor Information

Brandi C. Fink, Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico

Alyson F. Shapiro, T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University

References

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist. 2002;57:1060–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arias I, O’Leary KD. Semantic and perceptual discrepancies in discordant and non-discordant marriages. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1985;9:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett MS. A note on the multiplying factors for various chi square approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1954;16(Series B):296–298. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Arias I, O’Leary KD. The relationship of marital satisfaction and social support to depressive symptomatology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1986;8:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, OLeary KD. Marital discord and dysphoria: For whom does the marital relationship predict depressive symptomatology? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:405–420. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Sandeen EE, O’Leary KD. Depression in marriage: A model for etiology and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Benazon NR, Coyne JC. Living with a depressed spouse. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis JP, Stanton AL. Adjustment to a dyadic stressor: A longitudinal study of coping and depressive symptoms in infertile couples over an insemination attempt. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:433–438. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock HE, Harlow LL, Mulaik SA. Causation issues in structural equation modeling research. Structural Equation Modeling. 1994;1:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocols too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:184–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AJ, Benotsch EG, Wiebe JS, Lawton WJ. Coping with treatment-related stress: Effects on patient adherence in hemodialysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:454–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian JL, OLeary KD, Vivian D. Depressive symptomatology in maritally discordant women and men: The role of individual and relationship variables. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Christian-Herman J, O’Leary KD, Avery-Leaf S. The impact of severe negative events in marriage on depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20:24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Conway VJ, Terry DJ. Appraised controllability as a moderator of the effectiveness of different coping strategies: A test of the goodness of fit hypothesis. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1992;44:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Thompson R, Palmer SC. Marital quality, coping with conflict, marital complaints, and affection in couples with a depressed wife. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:26–37. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Attachment change processes in the early years of marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:783–802. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.783. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Karney BR, Hall TW, Bradbury TN. Depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction: Within-subject associations and the moderating effects of gender and neuroticism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:557–570. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehle C, Weiss RL. Sex differences in prospective associations between marital quality and depressed mood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:1002–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1980;21:219–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:107–113. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science & Medicine. 1988a;26:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988b;54:466–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:745–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollist CS, Miller RB, Falceto OG, Fernandes CLC. Marital satisfaction and depression: A replication of the marital discord model in a Latino sample. Family Process. 2007;46:485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Panter AT. Writing about structural equation models. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1995. pp. 158–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ilfeld FW. Coping styles of Chicago adults: Effectiveness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37:1239–1243. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780240037004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser HF. A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika. 1970;35:401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974;39:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Measuring Model Fit. David A. Kenny’s Homepage. 2011 Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Judd CM. Consequences of violating the independence assumption in analysis of variance. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:422–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kaniskan B, McCoach DB. The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Department of Psychology, University of Connecticut; 2011. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Essex M. Marital status and depression: The importance of coping resources. Social Forces. 1982;61:484–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Fisher LD, Ogrocki P, Stout BS, Speicher CE, Glaser R. Martial quality, marital disruption and immune function. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1987;49:13–34. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollack KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: An interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Weiss RL. Comparative evaluation of therapeutic components associated with behavioral marital treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:1476–1486. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.6.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE, Cronkite RC, Moos RH. Stress, coping, and depression among married couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:433–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien TB, DeLongis A. Coping with chronic stress: An interpersonal perspective. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Plenum series on stress and coping. New York: Plenum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Christian JL, Mendell NR. A closer look at the link between marital discord and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1994;13:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Riso LP, Beach SR. Attributions about the marital discord/depression link and therapy outcome. Behavior Therapy. 1990;21:413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Orathinkal J, Vansteenwegen A. The effect of forgiveness on marital satisfaction in relation to marital stability. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. 2006;28:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx CM, Buehler C, Helms H. Moderators of the link between marital hostility and change in spouses’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:540–550. doi: 10.1037/a0015448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Herceg-Baron R. Marital disputes and treatment outcome in depressed women. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1979;20:483–490. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(79)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AF, Gottman JM. The Specific Affect Coding System. In: Kerig PK, Baucom DH, editors. Couple Observational Coding Systems. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AF, Gottman JM. Effects on marriage of a psycho-communicative-educational intervention with couples undergoing the transition to parenthood, evaluation at 1-year post intervention. Journal of Family Communication. 2005;5:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AF, Gottman JM, Carrère S. The Baby and the Marriage: Identifying factors that buffer against decline in marital satisfaction after the first baby arrives. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:59–70. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storaasli RD, Markman HJ. Relationship problems in the early stages of marriage: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Family Psychology. 1990;4:80–98. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.4.1.80. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RL, Cerreto MC. The marital status inventory: Development of a measure of dissolution potential. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1980;8:80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM. Advances in psychiatric epidemiology: Rates and risks for major depression. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:445–451. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JD, Hobfoll SE, Lavin J. Resource loss, resource gain, and communal coping during pregnancy among women with multiple roles. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:645–662. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. Marital dissatisfaction and psychiatric disorders: Results from the national comorbidity survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:701–706. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Bruce ML. Marital dissatisfaction and incidence of major depressive episode in a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:674–678. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Kaiser R. Marriage and relationship issues. In: Dobson KS, Dozois DJA, editors. Risk factors in depression. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 363–384. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Weinstock LM, Uebelacker LA. Mood reactivity to marital conflict: The influence of marital dissatisfaction and depression. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Whisman MA. Relationship satisfaction instability and depression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:791–794. doi: 10.1037/a0021734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]