Abstract

Study Objectives:

Traditionally, sleep studies in mammals are performed using electroencephalogram/electromyogram (EEG/EMG) recordings to determine sleep-wake state. In laboratory animals, this requires surgery and recovery time and causes discomfort to the animal. In this study, we evaluated the performance of an alternative, noninvasive approach utilizing piezoelectric films to determine sleep and wakefulness in mice by simultaneous EEG/EMG recordings. The piezoelectric films detect the animal's movements with high sensitivity and the regularity of the piezo output signal, related to the regular breathing movements characteristic of sleep, serves to automatically determine sleep. Although the system is commercially available (Signal Solutions LLC, Lexington, KY), this is the first statistical validation of various aspects of sleep.

Design:

EEG/EMG and piezo signals were recorded simultaneously during 48 h.

Setting:

Mouse sleep laboratory.

Participants:

Nine male and nine female CFW outbred mice.

Interventions:

EEG/EMG surgery.

Measurements and Results:

The results showed a high correspondence between EEG/EMG-determined and piezo-determined total sleep time and the distribution of sleep over a 48-h baseline recording with 18 mice. Moreover, the piezo system was capable of assessing sleep quality (i.e., sleep consolidation) and interesting observations at transitions to and from rapid eye movement sleep were made that could be exploited in the future to also distinguish the two sleep states.

Conclusions:

The piezo system proved to be a reliable alternative to electroencephalogram/electromyogram recording in the mouse and will be useful for first-pass, large-scale sleep screens for genetic or pharmacological studies.

Citation:

Mang GM, Nicod J, Emmenegger Y, Donohue KD, O'Hara BF, Franken P. Evaluation of a piezoelectric system as an alternative to electroencephalogram/electromyogram recordings in mouse sleep studies. SLEEP 2014;37(8):1383-1392.

Keywords: automated, EEG/EMG, noninvasive, outbred mice, piezoelectric system, sleep

INTRODUCTION

Sleep research in mammals, including humans, almost exclusively relies on recording of the electroencephalogram (EEG) and the electromyogram (EMG). EEG/EMG signals provide information on the electrical activity of the brain and on muscle tone that together allows for the unambiguous determination of sleep-wake states.1–4 In addition to its use to determine sleep-wake states, quantitative analyses of the EEG signal itself have led to important insights into sleep regulation and to hypotheses on sleep functions.5–8

In rodents, EEG/EMG recording requires the surgical implantation of EEG electrodes on the surface of the cerebral cortex and EMG electrodes usually in the neck muscle tissue under deep anesthesia.4 In addition to expertise and time needed to perform the surgery, animals need several days to recover and to habituate to cables or, if a telemetry system is used, to large contraptions on either the head or in the peritoneal cavity. EEG/EMG therefore might not be the most appropriate method for large-scale studies that involve the recording of large cohorts of animals such as for genome-wide association studies or rapid screening for drugs. With this in mind, noninvasive methods to study sleep in rodents have been developed.9–12 One of these techniques is the piezoelectric (piezo) system, which uses a piezoelectric polymer film that transforms mechanical pressure into electrical signals with a voltage that is proportional to the compressive mechanical strength.13 When placed at the bottom of an animal cage, the piezo transducer can detect body movements with high sensitivity. The first use of such a sensor in animal behavior studies was performed to detect motor activity in response to drugs.14 In animals, like humans, the piezo system can be used to detect even more sensitive movements than locomotor activity, such as heartbeat and breathing.15,16 Recently, this technique has been used to distinguish sleep from wakefulness in mice, based on the regularity of the signal.17 In the sleeping mouse, the principal movements of the body are caused by respiration accompanied by movement of the chest wall, producing a rhythmic signal usually between 2 and 4 Hz. This regular signal can easily be distinguished from the high frequency and erratic signal displayed during wakefulness, associated with a variety of behaviors such as locomotor activity, climbing, eating, grooming, and even small movements of the head when the animal is resting. Piezo systems have also been used in human sleep studies to distinguish rapid eye movement (REM) sleep from non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep18–21 based on the regularity of the breathing. In these studies, piezoelectric sensors placed on the surface of a bed or piezoelectric belts were used to measure the breathing rhythm and to determine the sleep state.

Although comparisons with EEG/EMG determined sleep have been made,17 the reliability of the piezo system used here for mice has never been statistically evaluated. Moreover, aspects of sleep other than its duration have never before been quantified and validated. We assessed (1) if the two recording methods (i.e., EEG/EMG versus piezo) give similar results on the overall sleep/wake amount and distribution, (2) if the system is sensitive enough to provide information about sleep architecture and sleep intensity, and (3) if the piezo system is able to distinguish REM sleep from NREM sleep.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals and Housing Conditions

Data from nine male and nine female CFW Swiss Webster mice (Crl:CFW(SW); Charles River, Portage, MI, USA) contributed to this study. Mice were individually housed in polycarbonate cages (31 × 18 × 18 cm) in a temperature and humidity controlled room (25°C, 50-60% respectively) and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle (light on at 09:00,70-90 lux). Animals had access to food and water ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of the State of Vaud Veterinary Office, Switzerland.

Surgery

When the mice reached the age of 17 to 18 w, EEG and EMG electrodes were implanted under deep anesthesia (Xylazin/Ketamin intraperitoneally, 1 mL/kg) as previously described.4,22,23 Briefly, six gold-plated screws (diameter 1.1 mm) were screwed bilaterally into the skull, over the frontal and parietal cortex. Two of them served as EEG recording electrodes and the other four as anchors. As EMG electrodes, two gold wires were inserted into the neck muscles. The EEG and EMG electrodes were soldered to a connector and cemented to the skull. Animals were allowed to recover during 5 to 7 days before they were connected to the recording cables in their home cage for 6 days of habituation to the cable. In all, a minimum of 11 days passed between surgery and the first recordings.

Experimental Protocol

Mice were placed in the piezo device (Signal Solutions, LLC, Lexington, KY, USA) and recorded simultaneously with EEG/ EMG and piezo system consecutively for 72 h, starting at light onset (i.e., Zeitgeber time [ZT] 0). Mice were left undisturbed during the entire recording and had access to food and water ad libitum. The first recording day was considered as habituation to the piezo device and only the last 48 h of recording were analyzed here. The piezo apparatus consists of a unit of four individual transparent polycarbonate recording compartments. The floor of each compartment was covered with a polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) square film (17.8 × 17.8 cm, 110 μm thick), manufactured by Measurement Specialties, Inc. (Hampton, NY). The piezo films were covered with some litter and connected to a recording station.24

Data Acquisition

The analog EEG and EMG signals were amplified (2000x), digitized at 2 kHz, digitally filtered (low pass at 90 Hz; notch filter at 50 Hz; no high-pass filter), and subsequently stored at 200 Hz on a hard disc. The EEG was subjected to a discrete Fourier transformation to obtain power spectra (range: 0.75–90 Hz; frequency resolution: 0.25 Hz; time resolution: consecutive 4-sec epochs; window function: hamming). Hardware (EMBLA, A10 recorders) and software (Somnologica-3) were purchased from Medcare/Flaga (EMBLA, Thornton, CO, USA). Offline, the animal's behavior was visually classified as wakefulness, NREM, or REM sleep for each of the 4-sec epochs, based on the EEG and EMG signals as previously described.4 Shortly, the EEG during REM sleep is characterized by a regular, low-amplitude theta (5–9 Hz) rhythm and a low muscle tone, sometimes with twitches. During NREM sleep, the EEG amplitude is larger and dominated by slow oscillations including delta waves (1–4 Hz) concomitant with a low EMG. Wakefulness is characterized by a higher and variable EMG and a low-amplitude, mixed-frequency EEG. Four-second epochs containing artifacts were marked according to the state in which they occurred.

In parallel, piezo signals were acquired with the MouseRec acquisition system (Signal Solutions, LLC, Lexington, KY, USA). Output signals were amplified and filtered between 0.5 and 10 Hz. The amplified signals were analog-to-digital (A/D) converted at a sampling rate of 128 Hz using the LabView 7.1 software (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). Piezo signals were analyzed over tapered 8-sec windows at a 2-sec increment, from which a “decision statistic” was computed. This statistic reflects the regularity of the signal (both in frequency and amplitude) as well as the peak spectral energy. The more regular the signal with peak spectral energy in the range typical of breathing (1 to 4 Hz) and lower relative amplitude, the more likely the mouse is in a sleep state (higher magnitude for the decision statistic). A simple linear discriminate analysis was applied to extracted signal features for the sleep-wake classifier.24 The distribution of 2-sec decision statistic values obtained from the 2 days recording within an individual mouse yielded a clear bimodal distribution of 2-sec epochs with either high (i.e., sleep) and low (i.e., wakefulness) decision statistic values. The sleep-wake classification used an adaptive threshold based on the saddle point of the distribution of decision statistics collected over the 48-h recording. This saddle point was found automatically by determining the minimum variance sum for 2 sets of decision statistics resulting from the threshold.17,24

To compare the piezo-determined sleep-wake states with the corresponding EEG/EMG determined sleep-wake states, the two 48-h sleep-wake sequences were aligned within each individual. The piezo decision statistics of two consecutive epochs were averaged prior to the sleep-wake classification to match the 4-sec resolution of the EEG/EMG scores. Initial analyses revealed that using 4-sec epochs overestimated sleep in the piezo scoring as compared to EEG/EMG. Smoothing the decision statistic using a 4-min moving average improved overall agreement of sleep-wake state duration between the two recording methods (see Results).

Data Analysis

Analysis of the time course of the amount of sleep and wake was performed by calculating hourly values. For the EEG/ EMG signals, epochs scored as either NREM sleep or REM sleep were added to determine total sleep time. The resulting waveforms for piezo and EEG/EMG determined sleep were then compared within individuals. Correlation between piezoand EEG/EMG-determined sleep was also assessed for the 12 h dark and light periods as well as per 24-h day based on the 2-day recording.

In addition to quantifying the reliability of the piezo system in determining sleep quantity, we also determined and compared several measures of sleep quality. For both recording methods, sleep fragmentation was calculated using relative frequency histograms for episode duration as described previously.23 According to their length (counted by the number of consecutive 4-sec epochs), sleep and wake episodes were assigned to one of the nine bins of logarithmically increasing size (1, 2-3, 4-7, 8-15, 16-31, 32-53, 64-127, 128-255, 256- > 4-sec epochs with lower bin limits of 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024 sec). The frequency in each bin was expressed per hour of sleep (or wakefulness) by dividing episode number by the total duration of sleep (or wakefulness), in hours, present during the entire 48-h recording. In addition, the relative contribution of the episodes allotted to each time-bin to the total time spent asleep or awake was calculated. Because the difference between the two recording methods occurred mainly for the shorter episodes, the number of short awakenings (period of wakefulness lasting less that 4 epochs of 4 sec) and short sleep bouts (period of sleep lasting less that 15 epochs of 4 sec) were further compared.

To assess if the regularity of the piezo signal during sleep reflects sleep depth, the time course of EEG delta power and of the piezo decision statistic during NREM sleep were compared. EEG delta power was calculated by averaging the power density in the 1–4 Hz range for 4-sec epochs scored as NREM sleep. The average time course of EEG delta power was quantified in recording sections to which an equal number of NREM sleep epochs contributed; the light periods were divided into 12 such sections and the dark periods into six.23 EEG delta power values were then normalized by expressing them as a percentage of the individual mean value reached over the last 4 h of the second baseline day when EEG delta power is minimal during baseline. The time course of changes in the decision statistic was calculated in the same way and correlated with EEG delta power within individual mice. The time course of the average decision statistic within sleep and within wakefulness was assessed as well.

Because the regularity of the breathing rhythm, which is thought to contribute to the regularity of the piezo signal during sleep, is known to differ between NREM sleep and REM sleep,25–27 we assessed if the piezo system could be used to distinguish between these two sleep states. First, the mean value of the decision statistic was calculated for epochs scored as wakefulness, NREM sleep, or REM sleep. Second, the dynamics of the decision statistic at transitions between EEG/ EMG-determined sleep-wake states were calculated. Transitions were calculated as previously.22 Shortly, a transition was included in the analysis only if three or more consecutive 4-sec epochs of one state were followed by three or more consecutive epochs of another, thus excluding transitions from and to brief episodes of sleep or wakefulness. The dynamics of the decision statistic were determined over the 2 min preceding and following the transition. When the duration of the state under consideration for an individual transition was shorter than 2 min, the remaining 4-sec epochs (that were of a different state) were excluded from the analyses.

Statistics and Analysis Tools

TMT Pascal Multi-Target5 software (Framework Computers, Inc., TMT Development Corp., Brighton, MA, USA) was used to manage the data, SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), version 9.1 and Sigmastat V.3.5. (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL) for statistical analyses, and SigmaPlot 10.0 (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL) for graphics. To assess the effect of the recording method (i.e., EEG/EMG versus piezo) on different sleep/wake parameters (i.e., time spent in sleep and wake states, fragmentation of sleep and wake), one- or two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (rANOVA) were performed. Significant effects were decomposed using post hoc (paired) t-tests or Tukey honestly significant difference tests. Pearson correlation tests were performed to quantify the correspondence between the recording methods. Differences in total time spent asleep over 48 h according to the two recording methods, differences in the number of short sleep and wake bouts, and differences in the decision statistic value between the states were analyzed with t-tests. Statistical significance was set to P = 0.05 and results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Sex differences for EEG/EMG determined total sleep time did not reach significance levels and data from males and females were pooled in all the analyses.

RESULTS

Distribution and Amount of Sleep

Initial analyses revealed that using the 4-sec decision statistic to determine sleep for a given 4-sec epoch resulted in an overestimation of sleep time in the piezo scoring as compared to EEG/ EMG. This was, in part, because of short spikes in the decision statistic above threshold during waking that were too brief to be identified as sleep according to the EEG/EMG signal (see light-gray lines labelled “4-sec decision statistic” in Figure 1). We therefore decided to smooth the decision statistic. Incrementing window size at 1-min steps established that with a 4-min moving average, total sleep time, when calculated as an average over the entire 48-h recording period, no longer significantly differed between the two sleep recording methods (Figure 2). Although smoothing the data did improve overall agreement of sleep-wake state duration between the two recording methods, it diminished the number of brief awakenings during sleep. To accommodate this, sleep was only scored when both the 4-min and the 4-sec decision statistic values were above threshold. These modifications considerably improved scoring accuracy for the current dataset. For the 4-sec-by-4-sec comparison using the 4-sec decision statistic, accuracy amounted to 85.6 ± 1.1% (range: 74.9–91.3%; based on 43,200 epochs/mouse, n = 18). When requiring that both the 4-sec decision statistic as well as the 4-min moving average have to be above threshold to score sleep, accuracy increased to 90.0 ± 0.9% (range: 79.1–94.3%); i.e., a highly significant, 5.2 ± 0.5% improvement. Although additional, ad hoc adjustments and rules might have further increased the correspondence between the two data sets of this particular experiment, we did not want to further depart from the original scoring rules used in the “MouseRec” state determination algorithm.

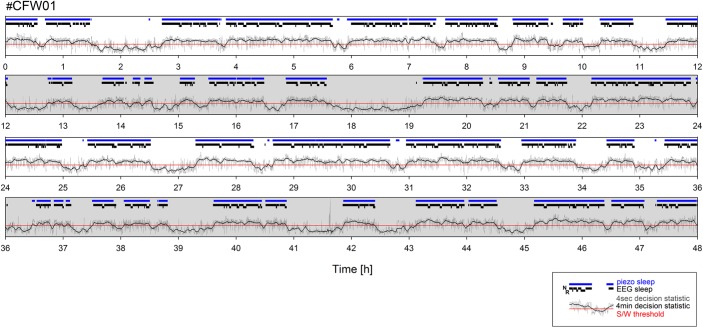

Figure 1.

Two-day recording of electroencephalogram/electromyogram (EEG/EMG)- and piezo-determined sleep in one individual male mouse (#CFW01). Each panel represents one 12-h segment of the 48-h recording (12 h dark periods with gray background). Within each panel blue and black horizontal bars represent piezo- and EEG/EMG-determined sleep episodes, respectively. EEG/EMG-determined sleep is further divided into non rapid eye movement and rapid eye movement (the lowered black bars) sleep. Horizontal red line represents the individually determined threshold that separates wake from sleep (S/W threshold). When, in a given 4-sec epoch, both the 4-sec decision statistic (thin gray line) and its 4-min moving average (thicker dark gray line) surpass the S/W threshold, sleep is called. Because of resolution of graphics, sleep interruptions < 1 min are not visible. Note that over the 48-h recording period no drift in the decision statistic was observed, permitting the reliable separation of sleep and wakefulness using a single, constant S/W threshold.

Figure 2.

Distribution and amount of total sleep time. (A) Time course of mean hourly values (± 1 standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 18) for time spent asleep based on the piezo system (filled circles) and on the electroencephalogram/electromyogram (EEG/EMG) (non rapid eye movement + rapid eye movement sleep; open circles). Although highly similar, the piezo system systematically overestimated sleep in the light periods (two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance with factors Method and Hour: Method P = 0.06, Hour P < 0.001, Interaction P < 0.001). Black horizontal lines on the top connect hourly intervals in which sleep time differed between the two recording methods (post hoc paired t-tests P < 0.05). Gray areas mark the 12-h dark periods. (B) A strong positive correlation between the amounts of sleep obtained with the two recording techniques was observed (Pearson correlation, light: r = 0.96, P < 0.0001, dark: r = 0.97, P < 0.0001, n = 432/ lighting condition). Hourly values and their linear regression curves are represented for the light (gray line, open circles) and dark (black line, filled circles) periods separately. Slopes of regression lines did not differ and did not deviate from unity (the 95% confidence intervals overlap). Outliers at 0 min/h EEG/EMG were all contributed by one mouse (#CFW07). (C) Average (± 1 SEM; n = 18) total time spent asleep over the 12-h light period significantly differs between EEG/EMG and piezo recordings (paired t-test, P < 0.01, represented by the star on top of the bar) whereas it does not differ for the 12-h dark period (paired t-test, P = 0.49).

With these modifications the changes in decision statistic tracked the occurrence of individual EEG/EMG-determined sleep episodes with high precision (Figure 1). The overall level and amplitude of the decision statistic was stable and a single, constant threshold reliably separated sleep from wakefulness over the entire 48-h recording period. Despite the general excellent correspondence between the methods to determine sleep, some discrepancies were observed that will be presented in the following paragraphs.

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the piezo system, total time spent asleep and the distribution of sleep in 18 mice were compared between the two recording methods. We first determined the total time spent asleep over the entire 48-h recording and although more sleep was observed with the piezo system, this difference failed to reach significance levels (EEG/ EMG 23.3 h ± 33 min; piezo: 24.4 h ± 46 min; P = 0.06; paired t-test, n = 18). We then calculated hourly values to construct a 2-day time course. The EEG/EMG- and piezo-determined average time courses closely matched and individual hourly values were highly and positively correlated (Figures 2A and 2B). Despite this overall excellent match, EEG/EMG and piezo scoring did differ with the piezo system scoring significantly more sleep during the light periods (Figure 2C). Moreover, for one animal, the piezo system detected a high amount of sleep for some hourly intervals in which, according to the EEG/EMG, no sleep was present (see Figure 2B, high values at 0 min/h EEG/EMG are all from one individual). Data from this individual were, however, not omitted from further analysis because only the simultaneous EEG/EMG recording allowed us to identify this problem.

The sleep-wake distribution observed here in the CFW outbred population showed some particularities when compared to commonly used inbred mouse strains.23 Similar to inbred mice, CFW mice have their main sleep period during the light period (i.e., the rest phase in nocturnal animals), and are mostly awake during the dark period. However, the data demonstrated an unusual bimodal distribution with two periods of wakefulness, a first initiated after dark, as is usual for mice, whereas the second follows the dark-to-light transition reaching levels of wakefulness at ZT2-3 comparable to the first period of wakefulness. The beginning of the main rest phase in CFW mice is thus delayed by 2-3 h compared to most inbred strains in which the rest phase starts at light onset (Figure 2A).

Sleep Quality and Depth

After assessing the reliability of the piezo in determining sleep-wake state quantity, we next asked whether measures gauging the quality of sleep and wakefulness could be equally estimated. We first determined the distribution of wake and sleep episode durations both with respect to the number of episodes of a particular length, as well as the relative time spent in each of the episode-duration categories. Compared to EEG/ EMG-determined sleep, the piezo classifier counted more short episodes of sleep and wakefulness (Figure 3). In particular, sleep episodes lasting less than 32 sec were overrepresented and, interestingly, more than twice as many waking episodes were counted that lasted two or three consecutive 4-sec epochs of wakefulness, specifically. Longer episodes of both states were, however, correctly represented by the piezo system, both with respect to the number of those episodes and their contribution to the total time spent in that state.

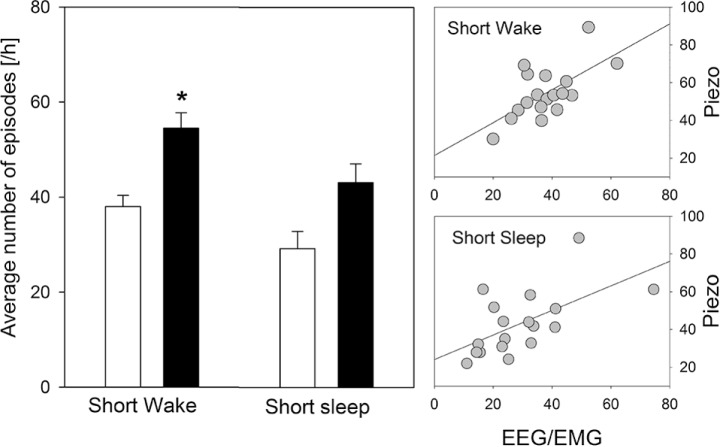

Figure 3.

Distribution of sleep-wake state episode duration. Left panels: Relative frequency distribution of episode duration for Wake and Sleep over nine consecutive time bins (4, 8-12, 16-28, 32-60, 64-124, 128-252, 256-508, 512-1024, > 1024 sec; lower bin limits indicated on the abscissa). For each recording method, vertical bars represent the mean (± 1 standard error of the mean; n = 18) number of episodes per bin expressed per hour of Sleep or Wake over the entire 48-h recording. Frequencies differed between the two recording methods (two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance [rANOVA], for both Sleep and Wake state, all factors and interactions P < 0.001). Right panels: For each state and each recording method, the contribution of time spent in each episode-duration bin is expressed as a percentage of total time spent in either Wake or Sleep over the entire 48-h recording (= 100%). The distribution of relative time spent in each bin (i.e., interaction) differed between the two methods (two-way rANOVA, Factor Method: Wake P = 0.09; Sleep P = 0.32; Factor Time bin: Wake and Sleep P < 0.001; Interaction: Wake P < 0.001; Sleep P = 0.03). Bins in which the frequency or amount differed between the two sleep recording methods, are indicated by a star (post hoc paired t-test, P < 0.05).

The frequency of short, spontaneous arousals from sleep are considered a measure of sleep continuity and sleep depth. In the rat and mouse a short arousal was defined as an awakening of one to four consecutive 4-sec epochs (≤ 16 sec23,28) or sleep episodes ≤ 60 sec.23 As expected from the previous analyses, the number of brief awakenings and short sleep episodes were higher when counted with the piezo system. However, despite the significant difference between the two recording methods, the piezo system could still predict EEG/EMG-defined sleep fragmentation because the results of the two methods were significantly and positively correlated (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of electroencephalogram/electromyogram (EEG/EMG)- and piezo-determined sleep fragmentation. Left panel: Mean (± 1 standard error of the mean; n = 18) number of short (< 16 sec) awakenings from sleep and number of short sleep bouts (< 60 sec) assessed by the piezo system (filled bars) and EEG/EMG (open bars) over the entire 48-h recording. The number of episodes is expressed relative to hour of sleep. The piezo system overestimated sleep fragmentation (* P < 0.05; paired t-tests). Right panels: Nevertheless, a significant positive correlation between measures of sleep fragmentation between the two recording methods was obtained (number of short awakenings: r = 0.63; P < 0.01; short sleep episodes: r = 0.60; P < 0.01; n = 18).

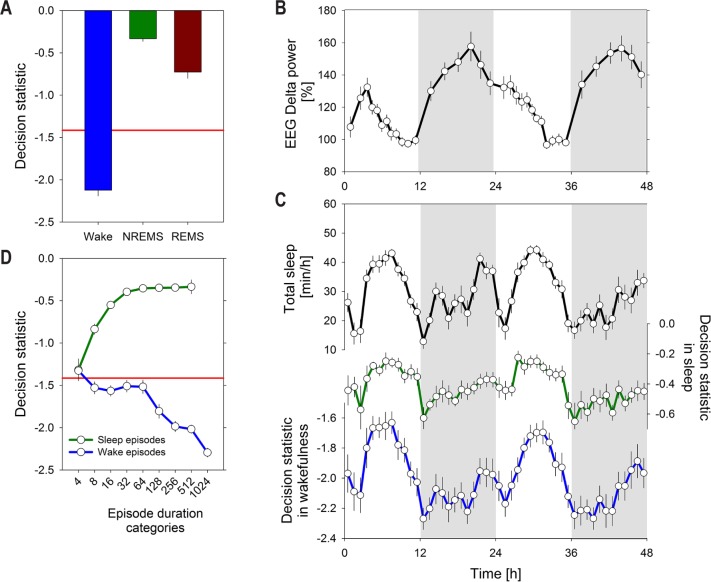

Depth of NREM sleep can be quantified by EEG delta power, a measure widely used to index not only sleep depth but also homeostatic sleep need.29,30 It has been shown in mammals that the “deeper” NREM sleep is, the more regular breathing becomes.31,32 As the piezo system is thought to detect regularity of breathing movements during sleep, the decision statistic within sleep could reflect sleep depth. A first observation consistent with this idea is that the average decision statistic is highest (i.e., most regular) in NREM sleep, intermediate in REM sleep, and lowest in wakefulness (Figure 5A). Analyses of the time course of EEG delta power levels reached during NREM sleep demonstrated that also in CFW mice EEG delta power decreases in periods when sleep is prevalent (i.e., the light periods) and reaches higher levels after periods when mice have been mostly awake (i.e., the dark periods; Figures 5B and 5C). Against our hypothesis, regularity of the piezo signal during sleep (Figure 5C) was negatively correlated with EEG delta power (r = -0.61, P < 0.001, n = 36). The decision statistic during sleep did, however, parallel the changes in the amount of time spent asleep (r = 0.77, P < 0.001, n = 48) suggesting the more the animal sleeps during a given hour, the more the decision statistic during sleep becomes higher and the signal more regular. We tested this also at the level of a sleep episode. In very short sleep episodes (4 sec), the mean decision statistic value was low, becoming gradually higher in longer sleep episodes reaching high constant levels for episodes longer than 32 sec (Figure 5D), supporting the idea that the regularity of the signal increases as sleep progresses. In addition, during periods during which mice sleep more, longer sleep periods are more prevalent (analysis not shown). The mean levels of the piezo statistic during wakefulness track the time course of total sleep time even more closely (Figure 5C; r = 0.89, P < 0.001, n = 48). Episode duration is likely to be a factor; the decision statistic during the shortest waking episodes (i.e., 4 sec) is indistinguishable from those observed during the shortest sleep episodes (Figure 5D). In longer waking episodes the piezo signal becomes less regular and, in contrast to sleep episodes, this relationship does not level off and the lowest decision statistic is observed in the longest waking periods that occur in the first hours after dark onset (analyses not shown).

Figure 5.

Changes in decision statistic within sleep and waking as a function of time-of-day and episode duration. (A) Mean decision statistic in electroencephalogram/electromyogram (EEG/EMG) determined Wake, non rapid eye movement (NREM), and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep significantly differed among the three states (one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance factor sleep-wake state and post hoc t-tests, P < 0.001). (B) Time course of EEG delta power in EEG/EMG determined NREM sleep. Symbols represent mean values obtained in percentiles of time spent in NREM sleep (12 in the light and 6 in the dark period) to which an equal number of 4 sec epochs contributed (see Methods). EEG delta power was expressed as a percentage of an individual reference calculated of the last 4 h of light periods (= 100%). (C) Time course of hourly mean values of EEG/EMG determined total sleep time (NREM + REM sleep; top, black curve) and the average decision statistic during sleep (middle, green curve), and wakefulness (lower, blue curve). Changes in the piezo statistic within sleep and within wakefulness strongly and positively correlate with the changes in total sleep time (see text). (D) Mean decision statistic as a function of duration of Wake (blue) and Sleep (green) episodes. Episodes were sorted into nine increasing time bins (4, 8-12, 16-28, 32-60, 64-124, 128-252, 256-508, 512-1024, > 1024 sec; lower bin limits indicated on the abscissa, as in Figure 3). Decision statistic in sleep is higher in longer episodes although levels saturate at ca. 32 sec. Decision statistic in wakefulness decreases as episode duration increases. In contrast to sleep, this relationship seems linear. In all panels, error bars indicate ± 1 standard error of the mean (n = 18). In panels A and D, the horizontal red line indicates mean threshold used to distinguish wake from sleep.

Can NREM and REM Sleep be Differentiated With the Piezo System?

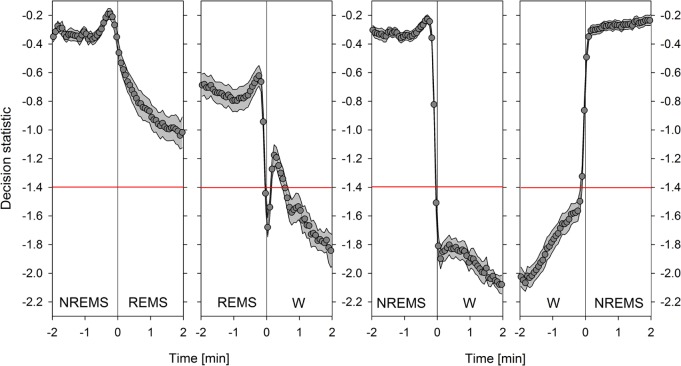

In humans as in other mammals, NREM sleep and REM sleep are characterized by distinct respiratory rhythms caused by changes in activity of the central neural systems responsible for the control of breathing. In NREM sleep, the frequency of breathing is low and regular, whereas in REM sleep the frequency increases and the breathing pattern becomes variable.18,33 In the current study, the decision statistic of the piezo system was higher during NREM sleep than during REM sleep, whereas average values in both states were higher than wakefulness and higher than threshold (Figure 5A). Close inspection of Figure 1 already shows that many REM sleep episodes are accompanied by a decrease in the decision statistic. Aligning all clear NREM to REM sleep transitions (see Methods for a definition) revealed a large decrease in the decision statistic, whereas values did remain above the sleep-wake threshold (Figure 6). Although this time course might not be as clear for an individual REM sleep episode and not even detectable for very short REM sleep episodes, these dynamics at transitions to and from REM sleep could help develop algorithms to differentiate the two sleep states. Interestingly, the transition from NREM to REM sleep was marked by an increase in the decision statistic just prior to the transition. Such transient increases in signal regularity were similarly observed at the REM sleep-to-wake transitions and the NREM sleep-to-wake transitions. Transitions in and out of wakefulness were abrupt and substantial, which illustrates why the decision statistic can reliably and precisely differentiate sleep from wakefulness. The NREM sleep-to-wake transition demonstrated that the largest decrease occurs just prior to the transition and that the last NREM sleep epoch will be more often called waking instead of sleep. Similarly, the last wakefulness episode prior to the onset of NREM sleep will statistically be called sleep more often because it already surpassed threshold. The REM sleep to wakefulness transition is intriguing; there, shortly after wake onset, the piezo system would again call sleep for about 24 sec. It has to be noted that these dynamics are average time courses based on many transitions and cannot be used to make reliable predictions concerning the dynamics at individual transitions. The REM to NREM sleep transition was not analyzed because not many such transitions reached our transition criteria (see Methods).

Figure 6.

Dynamics of the decision statistic at electroencephalogram/electromyogram (EEG/EMG)-determined sleep-wake state transitions. Transitions from non rapid eye movement (NREM) to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, from REM sleep to wakefulness (W), from NREM sleep to W, and from W to NREM sleep, from left to right, respectively, were aligned and the average time course of the piezo decision statistic (gray area delimites ± 1 standard error of the mean; n = 18) calculated at 4-sec resolution, first within (mean n = 161, 172, 568, 724/mouse/48 h, respectively; note that n decreases as time from 0 increases as most episodes are shorter than 2 min) and then among individuals (n = 18). Time 0 min delimits the last 4-sec epoch of the initial state and the first epoch of the subsequent state. Horizontal red lines indicate the mean threshold distinguishing wakefulness from sleep in the piezo system. Substantial and abrupt changes preceded both the NREM sleep-to-W and the W-to-NREM sleep transitions by ca. 10 sec. A more gradual decrease accompanied the NREM to REM sleep transition. The REM sleep-to-W transition dynamics were complex with a sudden decrease in the decision statistic in the 10 sec prior to W followed by sudden increase in the 10 sec after W onset, temporarily overshooting the decision statistic threshold. Interestingly, the changes out of both NREM and REM sleep were preceded by a transient increase in the decision statistic in the 40 sec prior to the change in sleep-wake state.

DISCUSSION

With this study, we performed a first, in-depth evaluation for a variety of sleep-wake variables of a piezoelectric system developed to noninvasively quantify sleep in mice. In a relative large data set consisting of 18 genetically diverse, male and female mice, analyzed at a high (4 sec) time resolution, we could directly assess the accuracy of the piezo system for a total of 777,600 sleep-wake scores. The comparison of sleep-wake variables obtained with EEG/EMG derivations and with the piezo system within the same individual mouse demonstrated that this technology can provide precise information about total sleep time and the distribution of sleep over the day. Moreover, measures of sleep consolidation could be determined with the piezo system that correlated with those obtained by the EEG/EMG. We also did observe some small but systematic discrepancies between the two methods such as the time spent asleep during the light period and in sleep consolidation. The analysis of the decision statistic within the two behavioral states suggests that applying a more dynamic decision threshold such that at times that sleep prevails its level is set higher, might further improve consistency between the two recording methods.

It should be emphasized that these two techniques are based on two distinct biological signals; i.e., brain activity on one hand and breathing regularity on the other. Therefore, one should accept small discrepancies between the results. For instance, subtle body movements or muscle twitches normally occurring during sleep but that are not accompanied by a sufficiently large change in the EEG to warrant scoring an arousal, seem to be detected by the piezo system leading to a higher number of short awakenings (and more disrupted sleep). The interest in the piezo system as a noninvasive alternative to EEG/EMG recordings is its use in screening large populations of mice for sleep-wake phenotypes. With this in mind, the differences observed in sleep time and fragmentation remain acceptable especially when these variables are predictive (i.e., correlate) with EEG/EMG determined sleep as we have shown here for sleep fragmentation. The most appealing aspect of the piezo system is certainly the time saved, not only because of the lack of a need for surgery and subsequent recovery but also because there is no need to manually annotate sleep-wake as is required when using EEG/EMG recordings.

Another alternative method has been proposed for sleep studies in rodents, based on the recording of locomotor activity to estimate sleep wake behavior.34 In particular, the use of a subcutaneously implanted magnet associated to a sensor placed beneath the cage that detects every movement of the magnet has been shown to accurately predict sleep and wake amounts compared to EEG/EMG recording. However, although less invasive than EEG/EMG implantation, this method still requires surgery to insert the magnet, and time for recovery. Moreover, no measure of sleep quality (e.g., sleep intensity) has been assessed with this method.

Another noninvasive, high-throughput sleep scoring system has been developed recently, making use of video recordings complemented with infrared beam breaking.10–12 This system can accurately estimate the total amount of sleep and wakefulness, the number of bouts as well as the duration of the sleep and wake bouts, under baseline conditions10 or in response to pharmacological treatments.11 The video system does, however, not allow for the determination of the fine structure of sleep because 40 sec of immobility is taken as threshold above which sleep is called. Smaller interruptions of sleep and short bouts of sleep, important to quantify the consolidation and thus quality of sleep,23,28 could be quantified with the piezo system. Another advantage of the piezo system is that the individual thresholds separating sleep and waking are automatically set, whereas with the video-based system scoring rules established for one inbred strain might not be optimal for other genetic backgrounds or experimental conditions affecting activity. With a genetically more diverse set of male and female mice without any intervention and at a much finer resolution, we reached similar accuracy levels as reported with the video based scoring (90% versus 92%)10 and a similar correlation for hourly values (0.97 versus 0.94).11

In humans, the difference in breathing rhythm regularity can be exploited to distinguish NREM from REM sleep, assessed with piezoelectric sensors placed on the surface of a bed or with piezoelectric belts.19–21,35 In the mouse also, a different pattern of breathing has been observed between NREM sleep and REM sleep, and this difference is influenced by genetic background.27 In our study, we observed a clear difference in the regularity of the signal between the two sleep states, suggesting that it might be possible to distinguish the two states with a different set of signal features. In our current study, these changes in the piezo-derived decision statistic did not have sufficient predictive power to automatically distinguish REM from NREM sleep. Algorithms could be developed that take, for example, the characteristic time course of the decision statistic at these transitions into account and use features focused on more subtle changes in periodicity and envelope of perturbations. Obviously, being able to automatically distinguish between these two sleep states would improve the utility of the piezo system. Similarly, with the video-based scoring system systematic changes in body posture between REM sleep and NREM sleep were observed, but these changes could not reliably predict the occurrence of REM sleep.12

The increase of the decision statistic prior to the NREM to REM sleep transitions is intriguing. It could indicate that breathing becomes temporarily more regular just preceding REM sleep onset. Studies performed in cats and rodents demonstrate that the onset of REM sleep is preceded by a short-lasting “intermediate state” characterized by high-amplitude spindles and low theta rhythm in the EEG.36 These spindle waves are characterized by a high and transient power in the sigma frequency range (11–15 Hz) that disappears when the animal enters REM sleep.22,37 This intermediate state is thought to be associated with a brief functional disconnection of the forebrain from the brainstem38 that could also be accompanied by changes in the respiratory rhythm, which might have been detected here with the piezo sensors.

The current study is the first to determine sleep in an outbred population of mice. The CFW outbred stock originates from a small number of Swiss-derived mice that have been subsequently randomly bred in large colonies over many generations, thus producing high allelic diversity and thus representing a genetically diverse population.39 Because of this diversity, the outbred mice are used in biomedical research on the assumption that they are more representative of a (genetically diverse) human population. These outbred mice therefore are of particular interest in large genetic studies such as genome-wide association studies.40 We are currently using the piezo system to study the genomic architecture of sleep in a large ongoing phenotyping project (directed by J. Nicod, the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford). With 6.4 h and 5.2 h of sleep in the 12 h light and dark periods, respectively, CFW mice are long sleepers compared to other inbred mice.23 The high sleep duration is mostly because of the large amount of time spent asleep observed in the dark period, which, in other strains, ranges between 2.0 and 4.5 h.23 In addition, the distribution of sleep in CFW mice over the 24-h day was somewhat peculiar in that consolidated bouts of wakefulness occurred in the first hours after light onset. This resulted in low average sleep levels in the second hour after light onset, approximating levels usually observed after dark onset when in most mice lines the main activity occurs. Along with genetic differences, experimental differences such as age and cage size could be contributing factors.

CONCLUSION

We demonstrate that the piezo system is a reliable alternative to EEG/EMG techniques in mouse sleep research that can be used as a tool for high-throughput screening of drugs or for genome-wide association studies. With the development of new efficient analysis algorithms that can distinguish NREM sleep from REM sleep, the piezo system is likely to become a widely used tool in rodent sleep research.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This study was performed at the University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, and supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF n°130825 and 136201 to Dr. Franken) and the state of Vaud supporting Ms. Mang, Mr. Emmenegger, and Dr. Franken. Dr. Donohue and Dr. O'Hara own Signal Solution LCC, a company producing and selling similar equipment as evaluated in this manuscript. However, no aspects of the research presented here were sponsored by Signal Solution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:591–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell IG. EEG recording and analysis for sleep research. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns1002s49. Chapter 10:Unit10.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deboer T. Technologies of sleep research. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1227–35. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6533-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mang GM, Franken P. Sleep and EEG phenotyping in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2012;2:1–20. doi: 10.1002/9780470942390.mo110126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daan S, Beersma DG, Borbely AA. Timing of human sleep: recovery process gated by a circadian pacemaker. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:R161–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.2.R161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger JM, Rector DM, Roy S, Van Dongen HP, Belenky G, Panksepp J. Sleep as a fundamental property of neuronal assemblies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:910–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasch B, Born J. About sleep's role in memory. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:681–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang X, Sanford LD. Telemetric recording of sleep and home cage activity in mice. Sleep. 2002;25:691–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pack AI, Galante RJ, Maislin G, et al. Novel method for high-throughput phenotyping of sleep in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2007;28:232–8. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00139.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher SP, Godinho SI, Pothecary CA, Hankins MW, Foster RG, Peirson SN. Rapid assessment of sleep-wake behavior in mice. J Biol Rhythms. 2012;27:48–58. doi: 10.1177/0748730411431550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McShane BB, Galante RJ, Biber M, Jensen ST, Wyner AJ, Pack AI. Assessing REM sleep in mice using video data. Sleep. 2012;35:433–42. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautschi G. Piezoelectric sensorics: force, strain, pressure, acceleration and acoustic emission sensors, materials and amplifiers. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Megens AA, Voeten J, Rombouts J, Meert TF, Niemegeers CJ. Behavioral activity of rats measured by a new method based on the piezo-electric principle. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;93:382–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00187261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyamoto Y, Yonezawa Y, Maki H, Ogawa H, Hahn AW, Caldwell WM. A system for monitoring heart pulse, respiration and posture in bed. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2002;38:135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato S, Yamada K, Inagaki N. System for simultaneously monitoring heart and breathing rate in mice using a piezoelectric transducer. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2006;44:353–62. doi: 10.1007/s11517-006-0047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flores AE, Flores JE, Deshpande H, Picazo JA, Xie XS, Franken P, et al. Pattern recognition of sleep in rodents using piezoelectric signals generated by gross body movements. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:225–33. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2006.886938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanfranchi PA, Fradette L, Gagnon JF, Colombo R, Montplaisir J. Cardiac autonomic regulation during sleep in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2007;30:1019–25. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung GS, Choi BH, Lee JS, Lee JS, Jeong DU, Park KS. REM sleep estimation only using respiratory dynamics. Physiol Meas. 2009;30:1327–40. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/30/12/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Ari J, Zimlichman E, Adi N, Sorkine P. Contactless respiratory and heart rate monitoring: validation of an innovative tool. J Med Eng Technol. 2010;34:393–8. doi: 10.3109/03091902.2010.503308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin JH, Chee YJ, Jeong DU, Park KS. Nonconstrained sleep monitoring system and algorithms using air-mattress with balancing tube method. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2010;14:147–56. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2009.2034011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franken P, Malafosse A, Tafti M. Genetic variation in EEG activity during sleep in inbred mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1127–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franken P, Malafosse A, Tafti M. Genetic determinants of sleep regulation in inbred mice. Sleep. 1999;22:155–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donohue KD, Medonza DC, Crane ER, O›Hara BF. Assessment of a noninvasive high-throughput classifier for behaviours associated with sleep and wake in mice. Biomed Eng Online. 2008;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orem J, Netick A, Dement WC. Breathing during sleep and wakefulness in the cat. Respir Physiol. 1977;30:265–89. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(77)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas NJ, White DP, Weil JV, Pickett CK, Zwillich CW. Hypercapnic ventilatory response in sleeping adults. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:758–62. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman L, Haines A, Klann K, et al. Ventilatory behavior during sleep among A/J and C57BL/6J mouse strains. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1787–95. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01394.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franken P, Dijk DJ, Tobler I, Borbely AA. Sleep deprivation in rats: effects on EEG power spectra, vigilance states, and cortical temperature. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R198–208. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franken P. Sleep homeostasis. In: Hirokawa N, Windhorst U, editors. Encyclopedia of neuroscience. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 3721–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mang GM, Franken P. Genetic Dissection of Sleep Homeostasis. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2013 Dec 14; doi: 10.1007/7854_2013_270. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farber JP, Marlow TA. Pulmonary reflexes and breathing pattern during sleep in the opossum. Respir Physiol. 1976;27:73–86. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(76)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirjavainen T, Cooper D, Polo O, Sullivan CE. Respiratory and body movements as indicators of sleep stage and wakefulness in infants and young children. J Sleep Res. 1996;5:186–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1996.t01-1-00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabiddu R, Cerutti S, Viardot G, Werner S, Bianchi AM. Modulation of the sympatho-vagal balance during sleep: frequency domain study of heart rate variability and respiration. Front Physiol. 2012;3:45. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storch C, Hohne A, Holsboer F, Ohl F. Activity patterns as a correlate for sleep-wake behaviour in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;133:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paalasmaa J, Waris M, Toivonen H, Leppakorpi L, Partinen M. Unobtrusive online monitoring of sleep at home. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2012. 2012:3784–8. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottesmann C, Gandolfo G, Arnaud C, Gauthier P. The intermediate stage and paradoxical sleep in the rat: influence of three generations of hypnotics. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:409–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franken P, Dudley CA, Estill SJ, et al. NPAS2 as a transcriptional regulator of non-rapid eye movement sleep: genotype and sex interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7118–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottesmann C, Gandolfo G. A massive but short lasting forebrain deafferentation during sleep in the rat and cat. Arch Ital Biol. 1986;124:257–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chia R, Achilli F, Festing MF, Fisher EM. The origins and uses of mouse outbred stocks. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1181–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yalcin B, Nicod J, Bhomra A, Davidson S, Cleak J, Farinelli L, et al. Commercially available outbred mice for genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]