Abstract

We report the intermolecular palladium-catalyzed reaction of tert-butyl propargyl carbonate with tryptamine derivatives or other indole-containing bis-nucleophiles. The reaction proceeds under mild conditions and with low catalyst loadings to afford novel spiroindolenine products in good to high yields.

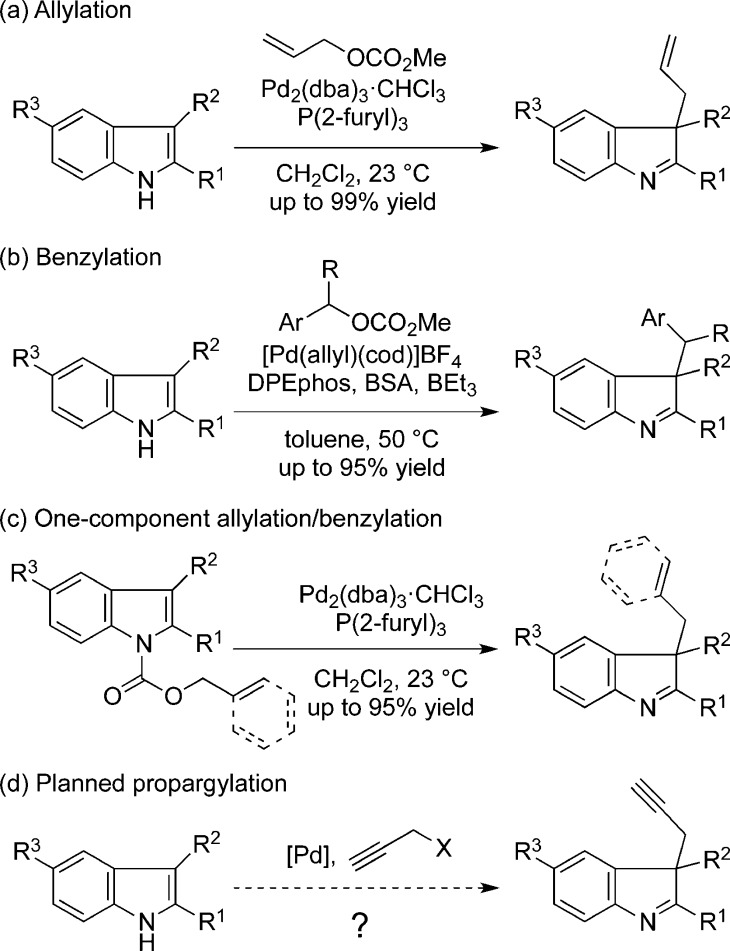

The unique challenges natural products present to synthetic chemists can inspire the development of useful methodology, often applicable to problems beyond those first encountered. In connection with an interest in monoterpene indole alkaloids, we have investigated several methods for the C-3 functionalization of indole derivatives. In our first report on this topic, we described a mild, Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative β-allylation of 2,3-disubstituted indoles to afford allylated indolenine products and demonstrated the applicability of this method to a range of functionalized substrates, including the natural products yohimbine and reserpine (Scheme 1, eq a).1,2 Subsequently, we developed effective protocols for the corresponding Pd-catalyzed benzylation reaction, which required a more challenging oxidative addition to the benzylic reactant (eq b).3 These two methods involved the linking of two separate components to yield functionalized indolenine products. In 2013 we reported what effectively amounts to an intramolecular variant of these processes, wherein a single indole component decorated with allyl or benzyl carboxylate is transformed into the respective β-allyl- or β-benzyl-indolenine (eq c).4a In the progressive development of this methodology, we have investigated the feasibility of the analogous Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative propargylation reaction (eq d). In contrast to the vast body of work on Pd-catalyzed allylation reactions, the corresponding propargylation reactions have received much less attention.5,6 As summarized below, rather than the anticipated β-propargyl indolenines, the reactions give a range of novel spirocyclized indolenines through a process wherein the propargyl reactant functions as a bis-electrophile. The reactions proceed under mild conditions, with low catalyst loadings, to give the spirocycylic products in good to high yields.7

Scheme 1. Pd-Catalyzed β-Functionalization of Indoles.

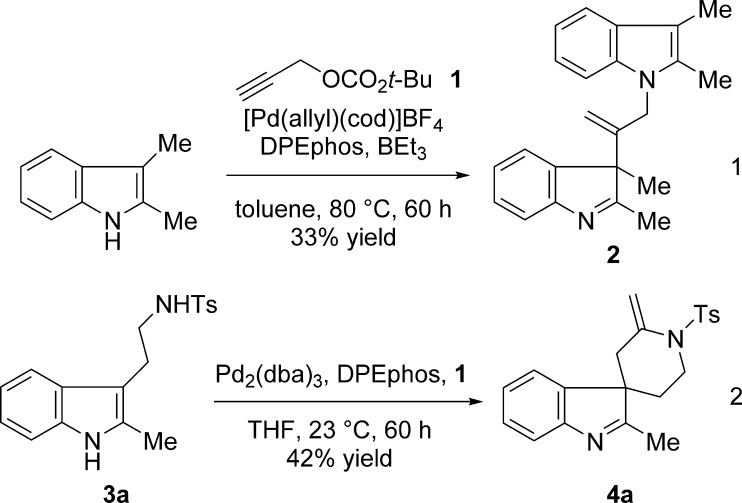

For the initial experiments, we examined the reaction between 2,3-dimethylindole and tert-butyl propargyl carbonate (1), under conditions that had proven effective for the corresponding allylation and benzylation reactions (Scheme 2, eq 1). Although initially no reaction was observed, a new compound gradually formed using a higher catalyst loading (10 mol %) at 80 °C. The major product of the reaction, rather than the β-propargylated indolenine, was “dimer” 2, arising from interception of the expected allenyl palladium intermediate by two indole units, one reacting at the β-carbon and the other at nitrogen (eq 2).

Scheme 2. Initial Experiments.

The above reactivity meant that indole substrates having in place an additional nucleophilic moiety would give rise to intricate spirocyclic compounds. Indeed, tosyl-tryptamine derivative 3a reacted at ambient temperature with propargylate 1 in the presence of 5 mol % palladium to afford compound 4a (42% yield), with indoline and piperidine conjoined through a spiro-linkage and adorned with functionality suitable for further transformations.8,9

Given the potential for this methodology to provide ready access to drug-like molecules, we carefully examined the reaction parameters in order to optimize the yield of the spirocyclization product. The conditions used with 2,3-dimethylindole gave the desired spirocyclized product in only 38% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Changing the solvent from THF to CH2Cl2 led to a significant improvement in yield and reaction rate (entry 2). Monodentate ligands such as trifuryl phosphine were largely ineffective (entry 3), and of the bidentate ligands screened Xantphos gave the best results: 90% yield after 35 min (entry 5). Other solvents and palladium sources were examined (entries 6–8) but provided only incremental improvements. Surprisingly, decreasing the concentration improved the reaction outcome, in the form of a higher product yield and shorter reaction time (entry 9).10 The spirocyclization was also competent under an ambient atmosphere, although the reaction gave a lower yield and required a longer reaction time (entry 10). The reaction worked well when the catalyst loading was reduced to 2.5 mol % (entry 11), or even 1 mol % (entry 12), which afforded the desired product in 98% and 87% yields, respectively. Lastly, the use of (R)-BINAP as the ligand provided the expected product in 80% yield and 16% ee (entry 13).11

Table 1. Optimization of Spirocyclization of Indole 3aa.

| entry | [Pd] | ligand | solvent (M) | 1 (equiv) | time (h) | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | DPEphos | THF (0.1 M) | 1.1 | 12 | 38 |

| 2 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | DPEphos | CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) | 1.1 | 3.5 | 95 |

| 3 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | P(2-furyl)3 | CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) | 1.1 | 3.5 | 5 |

| 4 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | DPEphos | CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) | 1.3 | 0.58 | 59 |

| 5 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | Xantphos | CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) | 1.3 | 0.58 | 90 |

| 6 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | none | CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) | 1.3 | 0.58 | 0 |

| 7 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | Xantphos | EtOAc (0.1 M) | 1.3 | 0.58 | 0 |

| 8 | Pd(OAc)2 | Xantphos | CH2Cl2 (0.1 M) | 1.3 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | Xantphos | CH2Cl2 (0.04 M) | 1.3 | 0.66 | 99 |

| 10c | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | Xantphos | CH2Cl2 (0.04 M) | 1.3 | 20 | 68 |

| 11d | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | Xantphos | CH2Cl2 (0.04 M) | 1.3 | 4 | 98e |

| 12f | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | Xantphos | CH2Cl2 (0.04 M) | 1.3 | 14 | 87e |

| 13 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | (R)-BINAP | CH2Cl2 (0.04 M) | 1.3 | 12 | 80g |

Reaction conditions: [Pd] (5.0 mol %), ligand (5.5 mol %), N2 atmosphere, 23 °C.

NMR yield calculated using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard.

Under ambient atmosphere.

[Pd] (2.5 mol %), Xantphos (2.75 mol %).

Isolated yield.

[Pd] (1.0 mol %), Xantphos (1.1 mol %).

16% ee.

Having defined optimal conditions for the propargylic spirocyclization, we set out to explore the scope of the reaction with regard to changes in the bis-nucleophilic indole species. Tosyl-tryptamines were competent substrates for the spirocyclization, although the reaction times were longer when an aryl group rather than an alkyl group occupied the indole C2-position (Table 2, entries 1–3). While less reactive than toluenesulfonamides, methanesulfonamides performed well when the reactions were carried out at a slightly higher temperature, with added organic base (entry 4). Extension of the tether length was tolerated provided the right withdrawing group was attached to the amine. Thus, tosyl-homotryptamine derivative 3e gave the expected product, containing a spiro-fused seven-membered ring, but the corresponding methylsulfonamide and methyl carbamate gave no product (entries 5–7). Shifting the sulfonamide component from C-3 to C-2 opened access to a different skeletal type, as seen in diamine 4h (entry 8). Likely due to steric interactions with the C-3 methyl group, cyclization occurs at the indole N–H. This observation is consistent with the formation of 2, wherein the “dimerization” event is terminated by N–C, rather than C–C, bond formation.

Table 2. Substrate Scope of the Indole-Propargylate Spirocyclizationa.

Reaction conditions: bis-nucleophile substrate (0.2 mmol), 1 (1.3 equiv), base (1.5 equiv), CH2Cl2 (0.4 M).

Isolated yields.

Two indole acetic acid derivatives were also examined for the propargylation reaction. Acetamide 3i reacted sluggishly and gave the desired product in low yield (entry 9). Reaction of the corresponding carboxylic acid (3j, entry 11) was carried out initially without added base. The reaction progressed slowly and produced only trace amounts of the desired lactone 4j, along with a mixture of products, from which was isolated “dimeric” product 5 in 19% yield.12 Since 5 is an allylic acetate, and hence a potential precursor to the desired lactone product 4j, we subjected it to standard reaction conditions, but with the inclusion of NEt3. After 24 h, approximately half of the “dimeric” compound had been transformed to the desired lactone. With the benefit of this understanding, the reaction of acid 3j was carried out in the presence of base and gave the spirocyclized lactone 4j in 52% yield (entry 10). The structure of lactone 4j is noteworthy since, unlike the other examples, the indole has formed a C–C bond to the central carbon of the propargyl unit.

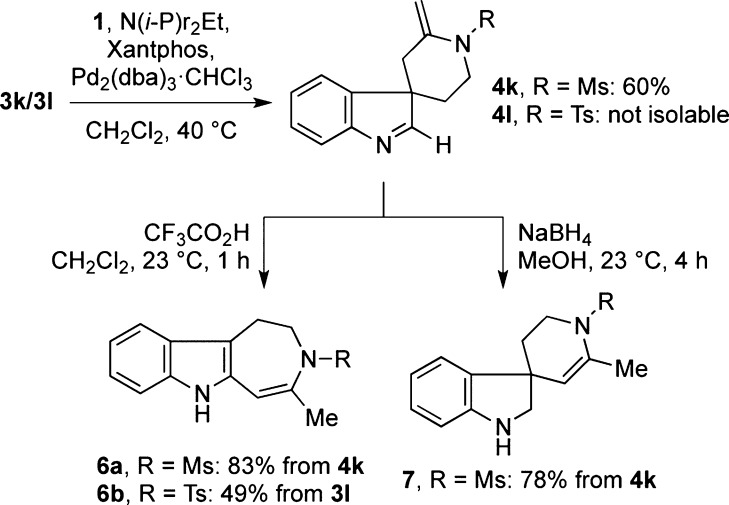

The spirocyclization of C2-unsubstituted tryptamine sulfonamides 3k and 3l paved the way to another interesting skeletal type (Scheme 3). Although both substrates gave the expected spiroindolenine products, the tosyl compound 4l was not isolable due to its ready decomposition upon exposure to air or silica gel. On the other hand, treatment of the spiroindolenine products with a mild acid triggered their rearrangement, possibly through a 1,5-sigmatropic shift,13 to tetrahydroazepinoindoles 6a and 6b, formed in 50% and 49% overall yields, respectively. Reduction with NaBH4 converted indolenine 4k to the corresponding spirocyclic indoline 7, with the double bond isomerized as endocyclic.

Scheme 3. Spirocyclization of Tryptamine Derivatives.

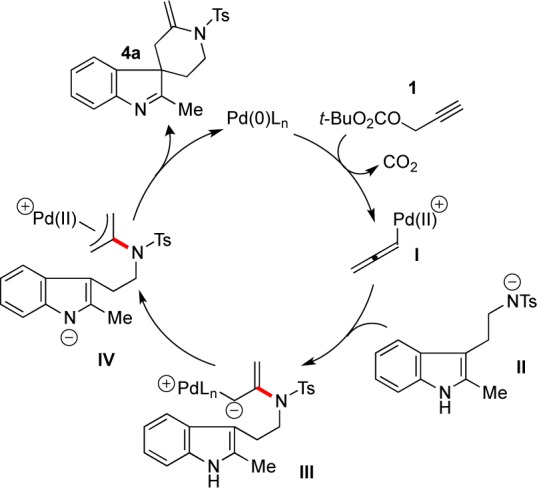

A plausible mechanism for the indole-propargylate spirocyclization reactions is shown in Figure 1. Oxidative addition of the Pd(0) catalyst to propargyl carbonate 1 with decarboxylative elimination of tert-butoxide is expected to generate cationic Pd(II)-allenyl species I. Deprotonation of the sulfonamide N–H by tert-butoxide allows for its addition to the central carbon of allene I to afford an allylic Pd-carbenoid III that upon protonation, ostensibly by the indole N–H, would produce Pd(II)-π allyl species IV. Coupling of the indole with π-allyl species IV followed by reductive elimination would yield the observed product, with regeneration of the catalyst.

Figure 1.

Proposed catalytic cycle.

In summary, we have developed a palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative propargylation reaction of indole-based bis-nucleophiles. The reactions proceed under mild conditions at low catalyst loadings and give rise to novel spirocyclic indolenines in good to high yields. The related spirocyclization of oxindole-based bis-nucleophiles and the use of chiral phosphines in such reactions are currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM069990 and P50 GM086145) is gratefully acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for all reported compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Kagawa N.; Malerich J. P.; Rawal V. H. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2381–2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reports of transition-metal mediated β-allylation of indoles, see, inter alia:; a Billups W. E.; Erkes R. S.; Reed L. E. Synth. Commun. 1980, 10, 147–154. [Google Scholar]; b Dieter J. W.; Li Z.; Nicholas K. M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 5415–5418. [Google Scholar]; c Bandini M.; Melloni A.; Umani-Ronchi A. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 3199–3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kimura M.; Futamata M.; Mukai R.; Tamaru Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4592–4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Prajapati D.; Gohain M.; Gogoi B. J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 3535–3539. [Google Scholar]; f Trost B. M.; Quancard J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6314–6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Bandini M.; Melloni A.; Piccinelli F.; Sinisi R.; Tommasi S.; Umani-Ronchi A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1424–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Zaitsev A. B.; Gruber S.; Pregosin P. S. Chem. Commun. 2007, 4692–4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Hoshi T.; Sasaki K.; Sato S.; Ishii Y.; Hagiwara H. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 932–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Xu Q.-L.; Dai L.-X.; You S.-L. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 97–102and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- a Zhu Y.; Rawal V. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhu Y. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- a Montgomery T. D.; Zhu Y.; Kagawa N.; Rawal V. H. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1140–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen J.; Cook M. J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 1088–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c See also ref (3b)

- For reviews of Pd-catalyzed propargylation, see:; a Tsuji J.Palladium Reagents and Catalysts: New Perspectives for the 21st Century; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, West Sussex, England, 2004; pp 543–562. [Google Scholar]; b Inuki S. Platinum Metals Rev. 2012, 56, 194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yoshida M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 60, 285–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reports of Pd-catalyzed propargylation see, inter alia:; a Tsuji J.; Watanabe H.; Miami I.; Shimizu I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 2196–2198. [Google Scholar]; b Tsuji J.; Sugiura T.; Yuhara M.; Minami I. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986, 922–924. [Google Scholar]; c Geng L.; Lu X. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 111–114. [Google Scholar]; d Tamaru Y.; Goto S.; Tanaka A.; Shimizu M.; Kimura M. Angew. Chem. 1996, 108, 962–963. [Google Scholar]; e Labrosse J.-R.; Lhoste P.; Sinou D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 9025–9028. [Google Scholar]; f Dominczak N.; Damez C.; Rhers B.; Labrosse J.-R.; Kryczka B.; Sinou D. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar]; g Duan X.-h.; Liu X.-y.; Guo L.-n.; Liao M.-c.; Liu W.-M.; Liang Y.-m. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 6980–6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Yoshida M.; Ueda H.; Ihara M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 6705–6708. [Google Scholar]; i Behenna D. C.; Mohr J. T.; Sherden N. H.; Marinescu S. C.; Harned A. M.; Tani K.; Seto M.; Ma S.; Novák Z.; Krout M. R.; McFadden R. M.; Roizen J. L.; Enquist J. A. Jr.; White D. E.; Levine S. R.; Petrova K. V.; Iwashita A.; Virgil S. C.; Stoltz B. M. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 14199–14223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Millán A.; Álvarez de Cienfuegos L.; Martín-Lasanta A.; Campaña A. G.; Cuerva J. M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 73–78. [Google Scholar]; k Yoshida M.; Sugimura C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 2082–2084. [Google Scholar]; l Schröder S. P.; Taylor N. J.; Jackson P.; Franckevičius V. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3778–3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The initial propargylation results with indole substrates were reported in the 2012 doctoral dissertation cited in ref (3b).

- During the course of these studies, two reports appeared on the propargylation of indole substrates, both utilizing a tethered alkyne for an intramolecular reaction:; a Nemoto T.; Zhao Z.; Yokosaka T.; Suzuki Y.; Wu R.; Hamada Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2217–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Iwata A.; Inuki S.; Oishi S.; Fuji N.; Ohno H. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We have found no other reports of a Pd-catalyzed intermolecular reaction between indole and propargyl carbonate.

- Small amounts of oligomeric byproducts form at higher concentration, and these appear to slow down the reaction. Addition of a small quantity of the oligomeric compounds significantly slowed the reaction versus the control reaction.

- The use of other chiral phosphines is currently under investigation, and the results will be reported in due course.

- The structure of “dimer” 5 was determined to be:

- For related rearrangements of indole derivatives, see, inter alia:; a Wang T. S. T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 19, 1637–1638. [Google Scholar]; b Baran P. S.; Maimone T. J.; Richter J. M. Nature 2007, 446, 404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zheng C.; Wu Q.-F.; You S.-L. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 4357–4365and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.